Abstract

Purpose

This article presents the emotional journey and experience of powerlessness of integrated care service users and carers.

Materials and methods

The experiences of seven integrated care service users and carers affected by complex conditions in a London borough were captured as video stories. The integrated care service coordinated a system of health and social care: primary care, community matrons, social workers, and the voluntary sector. The service was designed to respond to identified cases of high-risk individuals with long-term, multiple, and age-related conditions needing preventive interventions. The video stories were analyzed by researchers in collaboration with service users using a visual thematic qualitative approach. This report is part of an independent analysis of the integrated care service evaluation that used the experience-based codesign model.

Results

The findings are presented in the respective contexts of people with complex conditions and their carers. The overwhelming feelings and emotions of both were loss of control and power throughout their emotional journey, with family carers adopting a protective attitude toward the patients. Their experience of powerlessness was variable throughout their emotional journey. They were affected more strongly when in need of extra help and support and while they were undergoing the process of receiving extra services. When they were receiving help and support outside and within hospitals, some participants were empowered, gaining skills and knowledge by being provided with the mechanisms to cope with their condition at present and in the future.

Conclusion

Feelings of powerlessness were very common among integrated care service users and their carers. Powerless/empowerment has been poorly investigated to date. Visual methods and collaborative visual analysis with service users have proved to be powerful methods too, but have been rarely reported.

Keywords: visual methods, collaborative research, patients, complex conditions, UK

Introduction

The emotional journey throughout the diagnosis, treatment, and management of a complex condition may be challenging for those affected and their carers. It may involve grief, sorrow, and feelings of not having control or power over the condition and its everyday management. Patients may proceed through different stages in the course of their disease management, including crisis, hope, adaptation, new normal, and uncertainty.1 Caregivers and close family members also struggle under the impact of the disease.2 They are often required to assume numerous roles and make changes in their lives until they find themselves balancing a host of responsibilities. Caregivers’ own lives may be affected: the physical, emotional, social, and financial stress they can face may result in the neglect of their own needs, adversely affecting their quality of life.3–5

Feeling powerless may be common among patients and caregivers dealing with complex conditions. Powerlessness extends well beyond strictly medical and treatment-related issues to distressing feelings of insecurity and a threat to the patient’s social and personal identity.6 It is defined as occurring when an individual assumes the role of an object acted on by the environment rather than a subject acting in and on the environment.7 On the other hand, “patient empowerment” refers to the mechanisms enabling patients to gain control and make choices in their health and health interventions.8 More choice, more information, and more personalized care may be mechanisms that lead to empowerment of patients and carers, being described as the act or process of conferring authority, ability, or control.9

In the UK and elsewhere, services are expected to move to patient-led services, where they work with patients to support them with their health needs.10–13 Patients are moving toward obtaining control: they no longer accept being simply spectators, but expect to actively participate and be partners themselves in their own health care provision.14 The ultimate outcome of “empowerment” is often implicitly or explicitly referred to as being self-management of disease and treatment through the reinforcement of self-efficacy and control.6 The term “service user” is used here to capture those affected by complex conditions: users of integrated care services. The distinction is made with their carers and families.

A London National Health Service (NHS) trust wanted to redesign its integrated care services, a system of coordinating health and social care responding to identified cases of high-risk individuals for preventive interventions, set up in 2008. The system adopted a model of care using an integrated approach across health and social care organizations. The local authority was a supportive partner throughout, together with the primary care trust hosting a team of eight integrated care social workers, managed by the local authority and being co-located with the community matron team. Community matrons in England are highly experienced senior nurses working closely with patients in the community, mainly with those with a serious long-term or complex range of conditions. They provide, plan, and organize their care. The service therefore included primary care, community matrons, and social workers and the voluntary sector. The trust had conducted an evaluation in 2010–2011, aiming to evaluate the existing system, engaging patients and carers meaningfully in the evaluation, and to redesign the services accordingly. A secondary evaluation was then decided upon, to explore general service and care issues that were important for the patients and carers who had participated in the initial evaluation. The trust approached a university to conduct an independent review and analysis. In this paper, we present findings of the second evaluation that are relevant to the emotional journey: the feelings of empowerment or powerlessness of patients who used these services and their carers.

Materials and methods

Experience-based codesign

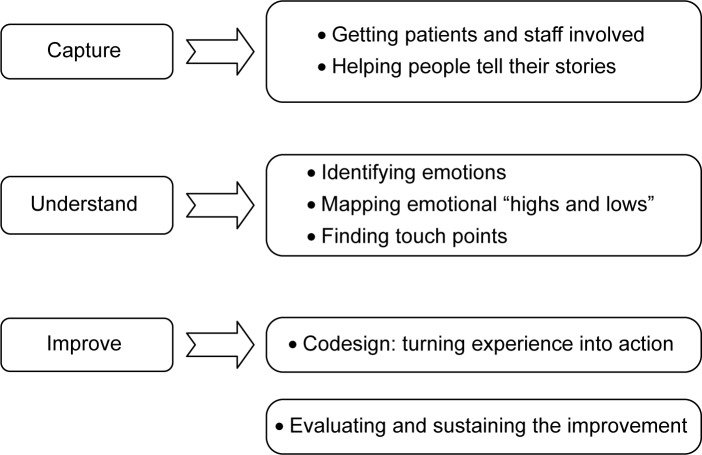

The evaluation involved experience-based codesign (EBCD), an innovative way of bringing patients and staff together to share the role of improving care and redesigning services to meet everyone’s needs.15,16 Although its principles can be similar to those of action research,17 this approach has been developed by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement in England as a way of helping frontline NHS teams make the improvements their patients really want. According to this, capturing and understanding the actual experiences of patients and carers is not enough. Only by understanding and evaluating their actual emotional experiences can services be enabled to improve and be transformed (Figure 1).16

Figure 1.

The experience-based codesign approach.

Sampling and documentation

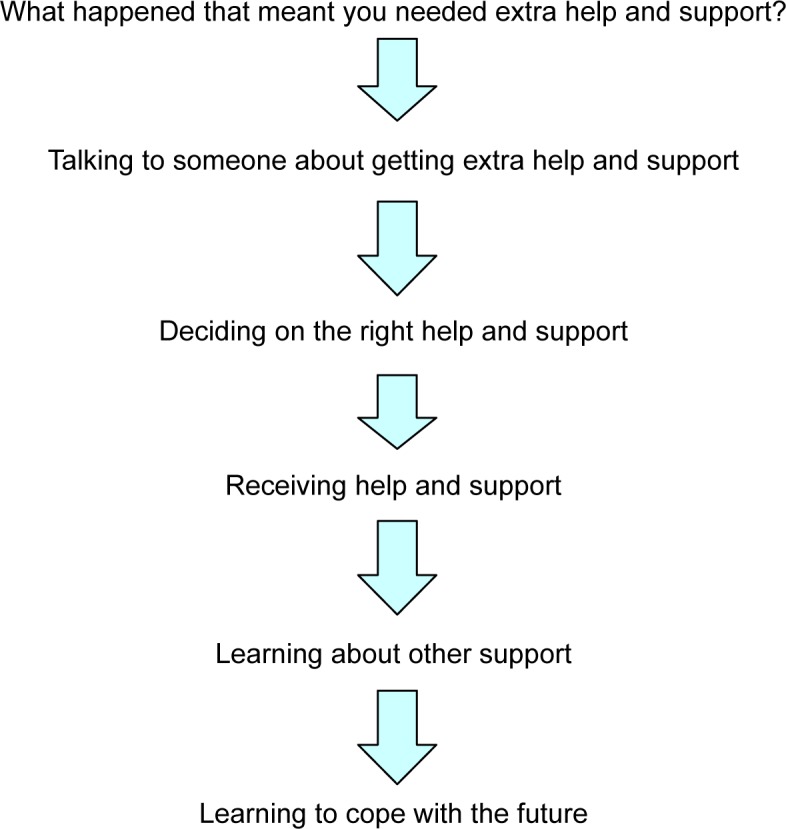

The project lead of the integrated care services in the trust developed the evaluation documentation. This included an introductory letter with information regarding the interview process, a consent form to ensure patients were fully informed and consented in writing to being filmed, and the editing of films for the purposes of service redesign. The interview was based on an interview “spine” with prompts to ensure the story was told in sequence, using open-ended questions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Experience based coproduction discovery interview: care spine.

Patients who had received the services were chosen at random, using a table of random numbers, by social workers and community matrons. The only inclusion criterion for patients was being fit to participate; carers could also take part. A total of 23 patients/carers were selected initially in February/March 2010. When approached, some were unwell, were in hospital, or unwilling to take part after further thought. A telephone rapport was built up between the remaining 18 potential participants by the project lead; information was given regarding EBCD, consent, and the filming and interview process, including the risk of emotional responses. Finally, seven patients/carers agreed to participate.

Method of data collection – video interviews

The trust commissioned a media company experienced in health and social care projects to film the participants in their own homes or a local studio if preferred. Details of the named media representatives were given to the participants by the project lead. This was followed up by a phone call from the filmmaker to help participants feel comfortable and at ease from the start.

The company supplied two journalists to conduct the interviews and to ensure they were impartial. Their input followed the interview “spine” prompts. Although a professional company was used, the integrated care project lead manager was present in all interviews but one, where the community matron was present, following the EBCD approach to bring service users and staff together.16

Seven video-recorded interviews were conducted in April/May 2010, all at the participants’ homes, apart from one conducted at the media studio. The unedited stories lasted from 30 to 60 minutes each, totaling 8 hours of unedited footage. This footage was then edited down to just 40 minutes to represent key themes in a documentary style.

Participants received both the edited and unedited film versions to compare, comment on, and ensure that all key points were included. None of them made any comments. The final edited film was viewed at an organized event by participants, other service users, project steering group members, and key stakeholders. Through facilitated discussion, they were asked to identify emotional high and low points (called “touch points” in the project) and where in the patient pathway they occurred. As a result the trust developed five redesign work groups, although these are not discussed in this paper.

Ethics

The primary evaluation was granted initial approval by the trust’s Research and Development Office, not requiring ethics committee (EC) approval as a service evaluation. Permission was sought for the secondary analysis from the trust’s Research and Development Office and the local EC chair by the integrated care project lead, who had obtained approval for the initial evaluation. A written response stated that it was considered a service evaluation, requiring no further permission. Following this, the media company was informed; the participants’ permission was then sought verbally and in writing. Finally, the research proposal was sent to the university EC for their information, not requiring approval as a service evaluation.

Participation in the secondary evaluation was voluntary; participants were informed they had the right to withdraw their permission at any time. No data would be used for purposes other than the research objectives. No references to names or identifiable characteristics would be made in the final project report or any subsequent publications. All data examined by the researchers would be anonymized in the analysis and writing up. A confidentiality agreement form stating that all data would remain confidential and be viewed for analysis purposes only would be signed by all researchers prior to viewing. All data, research processes, and outcomes, ie, videos and information on participants, remained confidential. They were to be stored in a locked cabinet and password-protected computer at the researcher’s office for 3 years, to allow time for publication of results.

Data analysis

The review and analysis of videos were conducted by MB collaboratively with two service users, NH and CL, who were independent of the project and trained in qualitative analysis. WC, an experienced researcher, also assisted.

A visual thematic approach was used, utilizing the principles of thematic analysis, as applied to video data. This involves analyzing the unedited videos to form codes, categories, and themes.18–20 The approach falls under the auspices of visual sociology, rather than visual ethnography or visual anthropology.21,22 The emphasis and the focus of the approach is on “what the eye can see” plus the “invisibility of the visual”, ie, the multidimensional, multisensory reality that is more than the one-dimensional evidence of talk that dominates research.23,24 In this context, cameras are analogous to audio recorders, but cameras have the potential to capture images and movements that give a fuller picture of reality, such as the raised eyebrow, the wave of a hand, the blink of an eye. Visual data include not only what people say therefore, but how they say it, their body language and symbols, and their perceived feelings and emotions through interaction with the interviewer, the setting, and the environment. It is recognized that everything is part of a complex visual communication system: the use and understanding of visual images is governed by socially established symbolic codes.25,26

For validity and reliability, three interviews were viewed by MB, WC, CL, and NH to bring multiple perspectives, including the service users’ unique perspective into the analysis. A day of viewing and initial analysis was arranged. The Visual Analysis Checklist together with the EBCD interview-discovery spine (Figure 2) were followed and completed by all researchers. In the last part of the day, these were discussed, and common themes and categories were identified, compared, and agreed upon.23

MB conducted an in-depth analysis by viewing the remaining videos; becoming more familiar with the data and trying to capture the “invisibility of the visual” by viewing all videos again and again in different speed modes.20,23,24 MB drafted a report for all researchers to convene and discuss the derived themes and categories and to draw preliminary conclusions. Finally, all read and commented on the final draft report.

Results

Interviewees’ characteristics

Participants were people with complex conditions, 75 years old or older, and family carers aged between 40 and 70 years. Two people cared for by participants had died recently. All participants were affected by various complex conditions, ranging from mental health issues to heart conditions and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. One interview was a double interview, where both the service user and her carer/son participated. In another, a service user, his main carer/wife, and his daughter participated (Table 1). Such arrangements were made according to participants’ preferences. The results of the interviews have been presented under two main themes, with their subsequent subthemes (Table 2):

- overwhelming feelings and emotions across their journey

- ○ people with complex conditions

- ○ family carers

- ○ both service users and family carers

- the emotional journey and experience of powerlessness/empowerment

- ○ the point when they were referred for/needing extra help and support

- ○ decision making on extra help and support

- ○ receiving help and support outside hospitals

- ○ the hospital experience

- ○ learning to cope with the future.

Table 1.

Interviewees’ characteristics

| Interview | Interviewee(s) | Age of interviewee(s), years | Sex of interviewee(s) | Condition | Hospital admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Service user | 75 | Male | Stroke, pacemaker, and epilepsy (unable to talk much) | February 2010 |

| Carer (wife) | 60s | Female | |||

| Daughter | 40s | Female | |||

| B | Service user | 85 | Female | Pneumonia/COPD | Many times |

| C | Carer (daughter; mother deceased in her 90s) | 70s | Female | Mental health issues – dementia | December 2009 |

| D | Carer (son; father deceased in his 90s) | 50s | Male | Age-related | June 2010 |

| E | Service user | 90 | Female | Infection at hospital, heart condition, panic attacks | Not known |

| F | Service user | 86 | Female | Emphysema and heart condition | Not known |

| G | Service user | 80s | Female | Dealing with bereavement and | Many times |

| Carer (son) (Other person – father deceased in his late 80s) | 60s | Male | severe arthritis (husband with Alzheimer’s) | 2005 (male deceased patient) |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

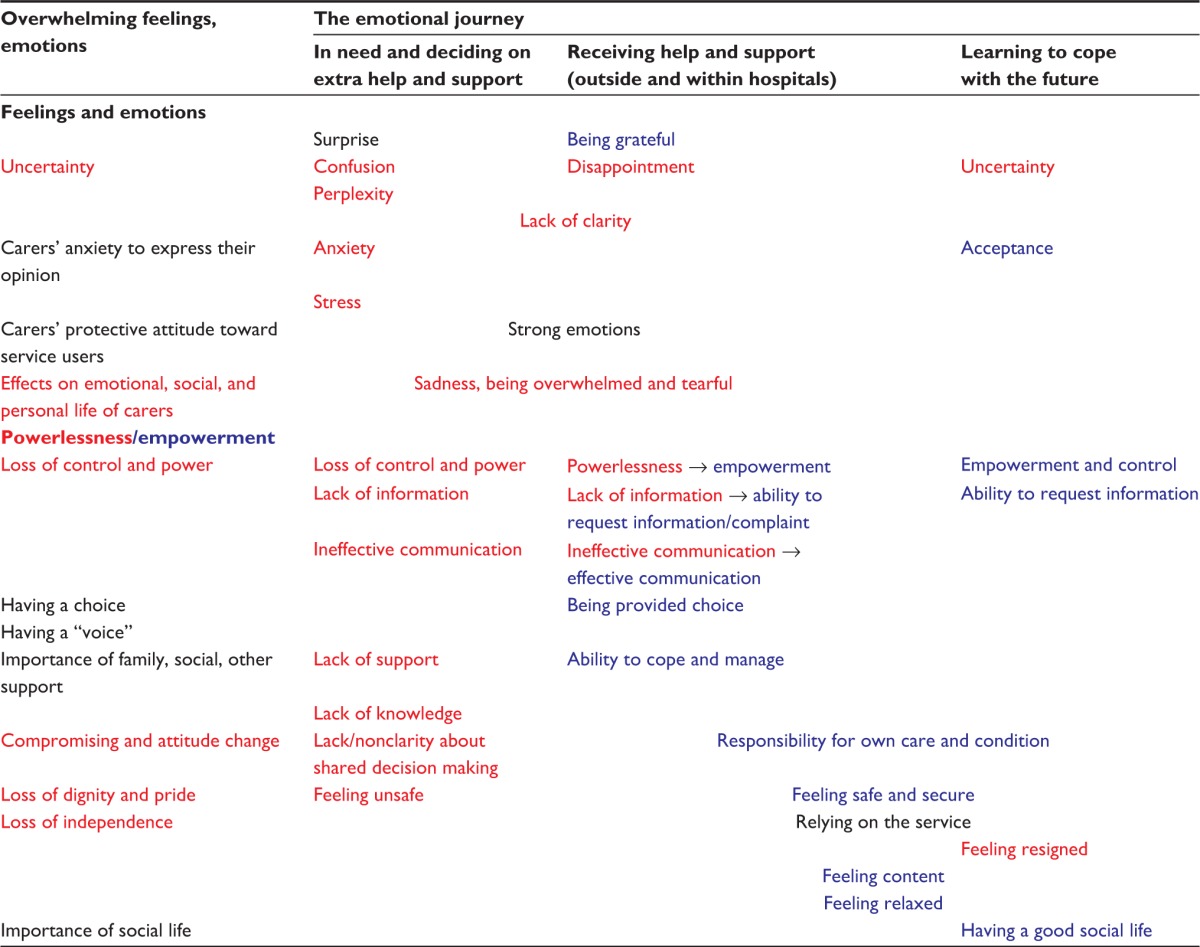

Table 2.

The emotional journey and experience of powerlessness/empowerment

|

Notes: Negative feelings and powerlessness presented in red font; positive feelings and empowerment presented in blue font; feelings neither negative nor positive presented in black font.

Overwhelming feelings and emotions

General feelings and emotions affecting people with complex conditions and their family carers throughout their journey arose during the interviews. These are presented below.

People with complex conditions

People with complex conditions often needed to be cared for every day; therefore, they lost control over their lives, their independence, and sometimes their dignity. On some occasions, they felt powerless, that they did not have pride anymore, that they needed to compromise and change their personality. However, they also felt that they should still have a “voice” and it needed to be heard, and that they should be asked about their preferences and be empowered in their interactions with services and health professionals. Individual professional carers were seen as supportive in most cases, and did the best they could. However, sometimes they seemed to do what they believed was best, rather than asking the service user for their preferences. The little things, however, made the difference in care, especially of older fragile people:

The other time I asked for a boiled egg, and she had the top chopped off, before she gives it to me, so it was cold […] I begun to find that I was getting what they wanted rather than what I wanted to eat myself! [smiles bitterly and lowers her eyes in dissatisfaction; service user, case E]

In some cases, special bonds were formed between professional carers and service users, especially with the regular carers, who seemed to understand their needs better. Service users felt more at ease and comfortable with them than with the one-off carers:

And these girls now, I’ve had them for some time, one in the evening and one in the morning, and they’re all nice girls […] I can make conversation. […] These girls, you know, they do have a program with me and laugh with me […] which is nice. [smiles and seems pleased; service user, case F]

Some users were able and keen to have a social life, and felt extroverted and sociable. For one person in particular, continuing to have a social life and going to the social club following her husband’s death was considered crucial. She encountered long delays for house adjustments for wheelchair access; these seriously affected her social life and well-being. These adjustments were not considered necessary by either the service user or her carer, as they thought that they did not affect her transport or transferability. For example, her carer had taken her out on a couple of occasions in his car. Black-cab and ambulance drivers had also not considered accessibility as problematic when they took her for appointments. The fact that she was not able to go out made her depressed. The importance of social life in elderly people’s lives was reinforced by her carer:

I had to wait for 6 months before I can go to the club […] because the transfer people said they could not get me up my chair out from the front door. Because I had like a little step. […] The transfer people reported it to their governor, right? It went from there. We had a meeting with them, and it took them 6 months. [gestures impatiently; service user, case G]

Family carers

When both family carers and service users were present, carers adopted a protective attitude toward the service users. This was exhibited, for example, with constant touching, eye contact, or leaning their body toward them. One carer was constantly monitoring her husband’s feelings by looking at him and observing his movements, reactions, and feelings, checking if he was in discomfort or in pain. She was monitoring what he was saying, and was interrupting with comments and prompts for more details. Carers and family members seemed anxious to express their opinion, to talk about things that could be improved, and perhaps give a more detailed and accurate picture than the one that the service user was describing, because of age or condition.

In addition, younger carers were much better informed of available systems and allowances. In one case, the carer had a very good knowledge of the care systems and agencies, patients’ rights, professionals’ responsibilities and legal issues surrounding them. Being protective of his mother, he had also compiled his own list of contacts relating to her care.

Carers not only dealt with the everyday care of service users but they also needed family, social, and other support to cope themselves. The importance of social networks was discussed. The burden of looking after someone with a complex condition was identified as enormous, with serious effects on emotional, personal, and social life. In one case, the carer suffered from depression and had suicidal thoughts as a result:

[…] because mum was obviously suffering from depression, after all she’s been through and she was heading for a nervous breakdown, I think, which was understandable. […] I think for 10 months she never stopped crying. […] There was not a day that Mum didn’t cry … [almost crying; daughter, case A]

On occasions that carers lacked family and social support, it was difficult for them to cope. A person with no other family explained the limitations to her personal and social life while caring for her mother over a long time. With no social life or holidays, she reached a point where she became resentful toward her mother:

[…] I didn’t have any social life, because everything revolved around my mother. Getting her up […] getting her meals. […] If I went out […] you’ve always wondered what you would find when you get home. […] And I have to enlist: a) I don’t have no family, so there were friends that were coming here to look after her. […] I mean, I didn’t have a holiday, I never had a holiday for 14 years. […] So, really, there was a lot of stress and a lot of pressures […] that you cope with, but then become a burden … (carer, case C)

Both service users and family carers

Although there were feelings and emotions distinct to service users or family members, there were some others common to both. In some cases, there was a change of roles as the provider in the relationship could not care for himself/herself anymore and the other person had to take up the carer role. The balance of the relationship changed; everyone had to get used to their new role and come to terms with it.

Issues of control and power were common. A rather articulate and knowledgeable carer, with a strong personality and nursing experience, summarized these issues indicating the different dynamics and the vulnerability of elderly people, especially of those who could not be represented by articulate carers like herself:

Overall, I was satisfied with the services I got, but I felt I had to battle, and if I hadn’t been of that type to do that, what would have happened, you know? If my mother had been on her own or had an elderly partner with her. I always felt we were having to battle. [using big gestures to express her frustration; carer, case C]

The emotional journey and experience of powerlessness/empowerment

In addition to the general issues, people with complex conditions and their carers were affected variably throughout their patient/carer journey (Table 2).

The point when they referred for/needing extra help and support

All service users had regular appointments either with their general practitioners (GPs) or hospital consultants. In most cases, they were not followed up by a single professional, but they visited various health professionals regularly. Prior to receiving integrated care services, they were receiving help and support from different agencies like district nurses, occupational therapists and carers.

Most commonly, a hospital consultant suggested the integrated care service, following a health care episode or a procedure. The consultant put them in contact with the service, or the matron. For some, it was a welcome, even if confusing, surprise:

I have been sick for [a] few years now, and then all of a sudden, he [the oxygen clinic doctor] was sending [named community matron] to me. I’ve been not well, and I think he was fed up with me, he was fed up of seeing me. […] No, I don’t know.[…] He just said that he was sending him to see to me. That’s what all! [laughing, perhaps entertaining the idea; service user, case B]

The empowering importance of good GP services was highlighted; they were recognized as the first contact points for other services. In one case, the GP was very supportive and understood and reconfirmed the need for extra support. He directed the service user and the carer to the appropriate services. In another, the GP suggested extra support, as he could see the difficulties of dealing with dementia and its progression.

In 2008. […]But my GP sensed that there would be a deteriorated situation [and] that we would need extra help.[…] In 2009, I went back to my GP, and he did all the formalities. [carer, case D]

Confusion and lack of clarity were common for participants in unexpected circumstances, such as when a stroke or a death occurred. They did not know anything about the condition, and were anxious, stressed, sad, and perplexed. During the interviews, they were emotional, sad, tearful, and in need of composing themselves, demonstrating the effect that the condition and their circumstances had had on their lives.

Decision making on extra help and support

In general, extra help and support was suggested as health professionals realized the need for it. In most cases, it was unclear if discussions had taken place or participants were given choices. It seems that they were told about the service rather than making shared decisions. In one case only, it was clear that there were discussions within the family prior to introducing the service and obtaining the user’s permission:

Everything was conducted with my father’s permission. Or be it. Because we tried to convince him that this was in his own interest, because he was [a] very proud man. [speaking seriously and cautiously; carer, case D]

Following the health professionals’ recommendations, community matrons or social workers contacted the service users to arrange home visits and assessments. Medical, social needs, and practical support assessments took place, measuring blood pressure and weight, making lists of prescribed medication, and need for carers, frequency of visits, equipment needed, and house adjustments, including ramps, etc, were also assessed at this stage. The needs of service users and carers were summarized in terms of what the service could offer. Again, it was unclear in some occasions how decisions were made:

When my husband died, I had a visit from the social worker and the therapist [OT]. They both decided I needed help after my husband died, and therefore I got the help from them. [speaking and expressing herself very quietly and passively; service user, case G]

Similarly, service users’ information needs were not discussed extensively. In one case, a total lack of information was identified. No information was provided or communicated by any health professional. This was a result of moving between wards, but it was felt that it could have been dealt with more effectively. The user and his family missed essential information and support not only from hospital professionals but also from voluntary organizations, such as the Stroke Association:

When we heard a stroke, we weren’t told about it at all. […] every time. […] we never got in touch with anybody, because we were moved from this ward up to cardiographic odd thing up there, then we came down […] we never knew what was all this about […] I thought he was coming home in a week, in a couple of weeks; I thought […] never ever ever I thought a stroke would be like this! No! [shows her dissatisfaction by emphasizing with big gestures and strong facial expressions; carer, case A]

Receiving help and support outside hospitals

There were negative and positive experiences with home help and support. Continuity of care and effective communication were very important for all service users who were elderly, fragile, and with complex care issues. They felt that the least the services could do was to keep them informed about appointments and regular checkups. This was not effective on one particular occasion:

There was this spell, and it was terrible last year, when he came he said he couldn’t book an appointment with me, because he hadn’t got his diary. And I found it very strange. […] This was October, and by January they [had] never contacted me. [using big gestures to show her dissatisfaction; service user, case E]

The same person felt that she needed to gain control and ensure that her voice was heard, by asking the community matron for explanations after not being contacted for 3 months. She felt empowered by doing this and being able to request appointments convenient to her. However, she acknowledged that other frail people would perhaps not be able to act the same way.

Two other service users felt empowered and in control with the extra care and support received. One considered that she could rely on the service; she felt safe and secure with the service provided through regular visits. The other believed that because she was given choice about emergency equipment – the installation of an emergency alarm – she was able to cope and manage with the available support, felt confident, and took responsibility for her own care and condition:

I’ve got an alarm there, and if I feel really bad, I push the button and they come and take me to the hospital. […] I try to manage, you know. I’ve got my walking stick, and I manage as well as I can with that. And my wheelchair, I’ve got a wheelchair. […] It gives you more confidence, you know, to know that I can ring [named community matron] … [smiling confidently; service user, case B]

Some participants had a content and relaxed attitude; they seemed able to live with their conditions and health problems comfortably, exhibiting a pleasant and joyful attitude:

Since I had this treatment, they are all so good […] I know I can rely on someone, they can write prescriptions, they send them off, etc […] I don’t have to do anything […] I am lucky!!! [talking happily with a big smile on her face; service user, case F]

The hospital experience

There were also negative and positive hospital experiences. Those who had experienced problems with hospital care and services appeared serious and overwhelmed with their encounters. Sadness and disappointment were evident; some people were tearful during the interviews. Feeling powerless and not having control of their situation was very common for participants when there was ineffective communication and a lack of information and good care. Again, they tried to gain some control, by asking for information or a particular service by themselves, or by involving the community matron and asking her to inquire on their behalf. The extract below shows how someone tried to obtain control over her situation, when she initially felt invisible and powerless:

[…] they are around your bed and they are talking about you, and when they finish, you say, “Excuse me, are you talking about me?” And they say [she uses an expression, like “What are you talking about?”] … And I said, “Well, it’s my body, and I would like to know what’s going on if you don’t mind”. And they were a bit shocked, but they turned around and they spoke to me, and after that, I take letters: a copy of what was sent to the doctor from the hospital and that. And I mean, I kept informed of what is going on. [service user, case F]

Examples of health and safety, hygiene, and dignity can paint the picture of powerlessness vividly. On occasions, staff did not have any empathy for the service users, did not show appropriate respect, or were insensitive. For example, a service user’s daughter was unable to find staff quickly to help with her father’s toilet and hygiene.

Obviously, dad was there on his own. He was shouting, “Toilet! Toilet!” I said, “Dad, don’t worry, I am here, I’ll get you a bedpan.” I went to ask the nurse. […] And she said, “See someone in a brown uniform.” And I said, “What difference does it make? I just want a bedpan!” By the time I found someone with a brown uniform, dad [had] soiled himself!!! I mean GOD, you know what I mean? I was so upset. Dad obviously was upset, he was shouting without anybody take[ing] any notice … [talking quickly, with tears in her eyes, raising her eyebrows, using facial expressions to show her disgust with the situation; daughter, case A]

Participants, however, felt empowered when they were offered good medical care and information They also felt empowered when dealing with staff who used simple language and plain English, and had good communication skills and pleasant and caring attitudes.

Carer: You could understand him. [nodding, while looking at her daughter]

Daughter: You could understand him, yes, but also he sort of explained everything in English, not in their terms or what have you, but […] and explained things. He was really a good doctor … fantastic! [case A]

Learning to cope with the future

Throughout their emotional journey of the integrated care service support, participants learned coping mechanisms essential for the future. Because of their health problems and physical condition, some felt resigned. Others had a relaxed attitude, felt content with the services provided, and adopted an overall positive attitude. Some felt that they had everything they needed, were empowered and in control, and were able to cope with the future:

[…] and they’ve got me the alarm, which makes me feel safe. […]It gives you more confidence, to know that I can ring [named community matron]. […]If I don’t feel well, I just ring him and he comes home. I wouldn’t have [need] anything else. […]That’s what I am saying, they couldn’t do much more than has been done already. No, I think he is very good. [seems happy and content, smiling; service user, case B]

On two occasions, the service supported carers with bereavement and continuing with their lives, following the death of their loved ones:

Even if I was not in the area, they both [community matron and social worker] phoned me […] they still phone up to ask how I am, how my wife is doing. … [The community matron] attended father’s funeral, [social worker] could not make it. […]I wanted to take them out […] for a meal to show our gratitude … [facial expression and mannerism show real appreciation and gratitude; carer, case D]

For some, though they did not respond to the question about learning to cope with the future as such, going out and having a good social life was considered an important coping strategy for both the present and the future:

[…] I don’t know, I just get on with life, I like life, I enjoy company, I like people, I am not a miserable person […] I do enjoy my life, I go down the club, I play darts, I play bingo … [smiling and laughing, raising her body slightly out of her chair for emphasis; service user, case F]

Discussion

Overwhelming feelings and emotions

This analysis confirmed the complexity and variability of the emotional journey and the process of powerlessness/empowerment that people with complex conditions and their carers go through. Other studies have identified emotional and empowerment aspects with patients with complex conditions, such as cancer, Parkinson’s, and dementia, and their carers.1–5 General issues arose, such as the need for recognition that they still have a “voice” to be heard and the need to feel empowered.

Other new findings, not identified elsewhere, emerged from the study. Carers had a generally protective attitude toward the service users; when present, they seemed anxious to express their opinion. Younger carers were better informed about systems and agencies, and thus they were better equipped to ask for extra support. The impact that caring for a frail person has on carers’ personal and social lives was also explored. Other studies have identified the caregiving impact on the lives of carers of patients with specific conditions.4,5 An alteration or adaptation of roles between people when circumstances change, ie, when the main emotional and support provider in the relationship needs caring, was also evident. This was evidenced in the McLaughlin et al study for carers of people with Parkinson’s disease, where many carers had taken on duties once performed by their relatives, such as driving, gardening, and bookkeeping.5

The emotional journey and experience of powerlessness/empowerment

Feeling powerless was common among patients and caregivers dealing with complex conditions. Confusion, perplexity, lack of clarity, anxiety, and stress expanded the participants’ sense of powerlessness, especially when they were in need or referred for extra care and support. These emotions were relevant to their specific circumstances and conditions. The empowering role and the engaging relationship with a good GP was however highlighted at this point of their emotional journey. Sheridan et al recognized that despite sociocultural and disease-related complexity, patients in general pursue the ideal of an engaged therapeutic relationship with an understanding clinician.27

Receiving extra help and support outside hospital services brought some control and empowerment, as well as safety and security with the service provided for some participants. Others felt that they needed to have their voice heard and gain control. Some felt able and supported to live on an everyday basis with their conditions. While in hospital, some participants experienced problems that made them feel powerless, sad, and disappointed. Lack of support, information, and communication, and insufficient care strengthened these negative hospital experience feelings. Lack of good medical care and treatment, affecting dignity and respect for certain service users, made them feel unsafe, vulnerable, and powerless while at the hospital. Powerlessness extends to distressing feelings of insecurity and threats to social and personal identity.6 Lack of information, knowledge, and support, and ineffective communication and unshared decision making affected their feelings of powerlessness. In many cases, this study’s participants assumed the role of an object acted on by the environment, rather than a subject acting in and on the environment.7

However, receiving extra integrated care services outside and within hospitals reinstated feelings of control and power for most participants. The support received provided the mechanisms enabling them to gain control and make choices in their health and health interventions.8 Although they relied on the service received, some felt that they had choice, were able to request information or make a complaint, and importantly, take responsibility for their own care. It needs to be acknowledged, however, that there were still problems with care, treatment, communication, and delays in obtaining extra support. The process was not easy for all, and the integrated care service did not achieve all its targets. Further empowerment could be achieved by taking a number of actions, although these are not addressed in this paper.

Importantly, through integrated care most participants obtained the knowledge and skills required to cope with their condition and become active partners with professionals.9 Taking responsibility and being able to self-manage, whenever it was possible, their disease and treatment through the reinforcement of self-efficacy and control may be considered the ultimate outcome of empowerment.6 Some participants were keen to continue having a good social and enjoyable life. The needs of older people, especially older women, are not often met in health care encounters. Lack of participation is often a reason for their dissatisfaction,28 but patient autonomy and choice need to be taken into account.29 Uncertainty for the future, however, was a common feeling, as identified in a similar study of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.1

Conclusion

The analysis of the video data captured the emotional journey and experience of powerlessness of the intensive care service users and their carers. A number of important issues relevant to the emotional journey when receiving extra help and support through integrated services were revealed. These included uncertainty, lack of clarity and information, loss of control and power when in need, and deciding on extra help and support, as well as feeling empowered and taking responsibility for one’s own care and condition, albeit with all the associated limitations and difficulties.

Issues of powerlessness/empowerment from service users’ and carers’ perspectives have been poorly investigated previously. Visual methods have been rarely used in this area, but promise a rich resource for investigation. In addition, collaborative visual analysis with service users proved valuable, and was not previously evidenced in the literature.

Challenges and limitations

The integrated care service was delivered to vulnerable adults over the age of 65 years. Recruiting service users and carers for the evaluation was challenging, because of the nature of the users’ health, age, and comorbidities. Another challenge was the editing of the initial videos. Ensuring that the film followed the interview spine was time-consuming. Further challenges were the ethics of collecting and analyzing visual data, the potential of cameras to disempower/empower, the reactivity of camera technologies in the research context, the limits to what and how much one can film, and the role video imaging could play in producing the research account or text to be taken into account.24

The project was designed by the trust and the media company, and the chosen design presented certain limitations. Although most people told their stories in their own living or dining room, not all seemed comfortable and open. The video takes were very close up, too, and on some occasions, we could not see other people present or their interactions, which would have made the visual analysis stronger. Additionally, the setting was often crowded, and this may have prohibited the participants from expressing views or concerns openly. The fact that the service lead was present in all interviews but one may have also had a prohibiting and restricting effect on the interviewees expressing their opinions. The interviews were conducted by two journalists – one more experienced than the other – using different styles, and this may have affected their outcomes. Finally, the initial evaluation had already been completed when the university was approached. All these factors may have directed and skewed the data collection and analysis.

Strengths

The EBCD approach used meant that the trust staff engaged with patients in an exciting, meaningful, and innovative way. They uncovered areas of concern regarding quality investigated by senior commissioning management, and for the first time they had video evidence of service user/carer experiences. The clinicians who viewed the film expressed a desire to “look inward” and reconsider their clinical practice, in particular their relation to patients, use of medical terminology, communication skills, and their overall assumptions about service delivery. In summary, the EBCD benefits were patient empowerment, possibilities for staff development and empowerment, and ability to set new standards in quality and performance with a better use of resources.

Taken as a whole, the data are very powerful: video stories allow powerful methods. In this analysis, we were able to explore influential nonverbal clues, body language, and interactions, not only between the interviewer, project manager, and the service user/carer(s), but also between service users and their family carers,21,24 that we would not have been able to capture otherwise. An additional strength of the analysis was that it was in collaboration with independent service users, such that data could be viewed and analyzed using different perspectives.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the London NHS Trust, who commissioned the work to us, and all the service users and carers who participated in the project. This publication was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London, UK. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health, UK.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Guilhot F, Coombs J, Szczudlo T, et al. The patient journey in chronic myeloid leukemia patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies: qualitative insights using a global ethnographic approach. Patient. 2013;6(2):81–92. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann M. ‘Journeys’ in the life-writing of adult-child dementia caregivers. J Med Humanit. 2013;34(3):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s10912-013-9233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasson F, Kernohan WG, McLaughlin M, et al. Living and coping with Parkinson’s disease: perceptions of informal carers. Palliate Med. 2010;24(7):731–736. doi: 10.1177/0269216310385604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotronoulas G, Wengstrom Y, Kearney N. Informal carers: a focus on the real caregivers of people with cancer. Forum Clin Oncol. 2012;3(3):58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin D, Hasson F, Kernohan WG, et al. Living and coping with Parkinson’s disease: perceptions of informal carers. Palliat Med. 2010;25(2):177–182. doi: 10.1177/0269216310385604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aujoulat I, Luminet O, Deccache A. The perspective of patients on their experience of powerlessness. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(6):772–784. doi: 10.1177/1049732307302665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Seabury; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Cathain A, Goode J, Luff D, Strangleman T, Hanlon G, Greatbatch D. Does NHS Direct empower patients? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1761–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrel C, Gilbert H. Healthcare Partnerships Debates and Strategies for Increasing Patient Involvement in Healthcare and Health Services. London: King’s Fund; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health . Creating a Patient-Led NHS: Delivering the NHS Improvement Plan. London: DH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health . Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: DH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: The Move Towards a New Public Health. Ottawa: WHO; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. Jakarta: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson E, Tritter J, Wilson R. Healthy Democracy: The Future of Involvement in Health and Social Care. London: Involve and NHS National Centre for Involvement; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The King’s Fund About the EBCD toolkit. 2010. [Accessed July 21, 2013]. Available from: www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/point-care/ebcd/about-ebcd-toolkit.

- 16.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement . Experienced Based Design. London: NHSIII; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reason P, Bradbury H. Handbook of Action Research. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haw K, Hadfield M. Video in Social Science Research. London: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks M. Visual research methods. 1995. [Accessed January 20, 2015]. Available from: http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU11/SRU11.html.

- 22.Banks M. Visual research methods. In: Miller RL, Brewer JD, editors. The A–Z of Social Research. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason J. Qualitative Researching. London: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison B. Seeing health and illness worlds – using visual methodologies in a sociology of health and illness: a methodological review. Sociol Health Illn. 2002;24(6):856–872. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The BSA Visual Sociology Study Group What is visual sociology? 2010. [Accessed November 5, 2010]. Available from: http://www.visualsociology.org.uk/whatis/index.php.

- 26.Pink S. Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheridan NF, Kenealy TW, Kidd JD, et al. Patients’ engagement in primary care: powerlessness and compounding jeopardy. A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18(1):32–43. doi: 10.1111/hex.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts SJ. Empowering older women: strategies to enhance their health and health care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(5):664–670. doi: 10.1177/0884217504268872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyttle DJ, Ryan A. Factors influencing older patients’ participation in care: a review of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2010;5(4):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]