Abstract

Objective

Millions of patients suffer from the disabling hand manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), yet few hand-specific instruments are validated in this population. Our objective is to assess the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ) in RA patients.

Methods

At enrollment and at 6 months, 128 RA patients with severe subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joints completed the MHQ, a 37-item questionnaire with 6 domains: function, activities of daily living (ADL), pain, work, aesthetics, and satisfaction. Reliability was measured using Spearman correlation coefficients (r) between time periods. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s α. Construct validity was measured by correlating MHQ responses with the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale 2 (AIMS2). Responsiveness was measured by calculating standardized response means between time periods.

Results

The MHQ demonstrated good test-retest reliability (r = 0.66, p<0.001). Cronbach’s α scores were high for ADL (α=0.90), function (α=0.87), aesthetics (α=0.79), and satisfaction (α=0.89), indicating redundancy. The MHQ correlated well with AIMS2 responses. Function (r=−0.63), ADL (r=−0.77), work (r=−0.64), pain (r=0.59), and summary score (r=−0.74) were correlated with the physical domain. Affect was correlated with ADL (r=−0.47), work (r=−0.47), pain (r=0.48), and summary score (r=−0.53). Responsiveness was excellent among arthroplasty patients: function (SRM=1.42), ADL (SRM=0.89), aesthetics (SRM=1.23), satisfaction (SRM=1.76), and summary score (SRM=1.61).

Conclusions

The MHQ is easily administered, reliable and valid to measure rheumatoid hand function, and can be used to measure outcomes in rheumatoid hand disease.

Keywords: The Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ), rheumatoid arthritis, hand surgery, outcomes, validation

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic, inflammatory autoimmune disease that results in substantial disability and premature death for over 1 million individuals in the United States.1 Rheumatoid hand disease is caused by progressive and irreversible inflammation of the synovial tissue, and joint destruction occurs early in the course of disease. Hand deformity and dysfunction is the most common manifestation of RA; 70% of RA patients experience disfiguring and painful rheumatoid hand deformities. Up to 30% of patients have radiographic evidence of disease at the time of diagnosis, and over 60% have radiographic joint changes within 2 years of diagnosis.2 Unlike other chronic diseases, such as osteoarthritis or hypertension, patients are typically diagnosed with RA in young adulthood, and this disease profoundly interferes with their future work productivity, their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), and their social interactions. On a societal level, the effect of these lost wages and expensive medical therapies consume approximately $3.6 billion per year.3, 4 Unfortunately, a standardized, hand-specific instrument to measure rheumatoid hand function remains elusive, and there are few accepted guidelines for defining hand disability among RA patients.

A variety of methods have been used to describe health outcomes related to the hand manifestations of RA. These have ranged from objective measures, such as painful joint counts or grip strength, to more subjective measures, such as patient satisfaction scores and quality of life measures. Although single, objective measures of function, such as range of motion, degree of finger extension lag, grip strength and pinch power, are relatively simple to obtain, they often do not capture the full extent of patient disability. More complex functional tests can include a battery of tasks, such as the Jebsen-Taylor test, the Grip Ability Test, or the Arthritis Hand Function Test.5–7 These may provide a better assessment of difficulty with activities of daily living, but often do not account for other important endpoints such as pain, aesthetics, and patient satisfaction.8

Patient perception of health status, as measured by self-administered instruments, has been shown to be a better predictor of functional status and disability compared with objective measures.9 Many instruments have been used to define patient-related outcomes in RA patients, ranging from general quality of life to hand-specific surveys. General health assessment instruments, such as the visual analog scale (VAS), the SF-36 and its derivations, and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), may offer a global assessment of functioning, but they are not sensitive to detect the amount of patient disability related specifically to RA or to hand dysfunction.8, 10–12 Other authors have used hypothetical scenarios to explore patient-related outcomes, using utility measures to estimate future quality of life. Although such models are useful in decision analyses, they are often difficult to implement in clinical practice and the concepts may be challenging for patients to grasp.13,14 An ideal instrument should be hand-specific, and include not only patient perception of function, but also measures of pain, satisfaction, and hand appearance.

We have prospectively evaluated rheumatoid arthritis patients from three centers in the United States and England to determine patient outcomes following surgical intervention (silicone arthroplasty) for metacarpophalangeal joint deformity using the Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ). We have achieved excellent long-term follow-up in this sample, and we have a unique opportunity to describe the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the MHQ in rheumatoid patients. The MHQ is a self-administered questionnaire that contains 37 items and requires approximately 15 minutes to complete, and has been used successfully in the RA population in prior work.15–25 We hypothesize that the MHQ will accurately and reliably define rheumatoid hand performance, and effectively measure clinical change in hand function over time.

Methods

The study sample consisted of patients diagnosed with RA by their rheumatologists and referred to one of the following three institutions: The University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI), Curtis National Hand Center (Baltimore, MD), and the Pulvertaft Hand Centre (Derby, England). The study sample is part of a larger prospective study supported by the National Institutes of Health regarding the use of silicone metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty (SMPA) for joint deformities due to RA, which has been described in detail elsewhere.26, 27 Patients were included in the study if they were diagnosed with RA, had severe metacarpophalangeal joint deformity and were deemed appropriate candidates for surgical reconstruction. Additionally, subjects were eligible if they were 18 years of age or older, and able to complete the study questionnaire in English. Patients were excluded from the study if their comorbid conditions prohibited surgery, they suffered from additional hand conditions (swan-neck, boutonniere deformities, extensor tendon ruptures) that would require intervention beyond SMPA arthroplasty, or they had previously underdone MCP joint replacement. After enrollment, participants either elected to receive SMPA or remained as controls. Data were collected from subjects at the time of enrollment and at a 6 month follow-up time. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, Curtis National Hand Center, and the Pulvertaft Hand Centre.

All subjects completed the MHQ, which has been previously validated for use in a wide range of patient samples.15–20 The MHQ yields an overall summary score of hand function, as well as scores for 6 specific scales: hand function, ability to complete activities of daily living (ADL), pain, work performance, aesthetics, and patient satisfaction. Scores for each domain range from 0 to 100, and higher scores indicate better performance for all domains with the exception of pain.

Subjects also completed the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 questionnaire, a 45- item, self-administered outcomes tool designed to assess health status in patients with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis.28 The AIMS2 is designed to provide a global, self-reported assessment of patient health status, and yields information in 4 domains including physical functioning, affect, symptom, and social interaction. Scores range from 1–10, with lower scores reflecting better health.

All subjects underwent the following assessments to provide objective and reproducible measures of hand function at baseline and subsequent follow-up: grip strength, lateral pinch, 2-point pinch, and 3-point pinch, all measured in kilograms. Subjects also completed the Jebsen-Taylor test, which is a seven part, standardized test designed to assess a subject’s ability to complete everyday hand-related tasks.29 The writing portion was not included in this analysis due to difficulty of interpretation relating to hand dominance. Time to complete each task was measured in seconds.

Outcomes

Reliability

Reliability is defined as the ability of an instrument to consistently or precisely measure a concept of interest.30 In this study, we measured two aspects of reliability of the MHQ, the test-retest reliability of the MHQ and the internal consistency of the 6 scales within the MHQ. Test-retest reliability implies that the survey yields similar results from consecutive administration to a subject. To determine the test- retest reliability of the MHQ, we compared responses for each domain of the MHQ at baseline and at the 6 month follow-up interval. We used responses regarding the symptomatic hand of the control patients who did not undergo SMPA and the non-operated hand of the SMPA patients. The degree of correlation between the consecutive responses was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Additionally, we used paired t-tests to determine the average difference in score for each domain between these time periods to determine if these means were significantly different. A mean difference of 0 indicates perfect test-retest reliability.

We determined the internal consistency, or homogeneity, of the items included in each scale of the MHQ by calculating Cronbach’s α for each of the six scales in the MHQ. Cronbach’s α is a measure of the homogeneity of items within a scale, and is based on the number of items included, and their degree of correlation according to the following formula:

in which N is the number of items in the scale, v̄ is the average variance between subjects in the sample, and c̄ is the average covariance between items among the subjects in the sample. Cronbach’s α values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater internal consistency. In general, Cronbach’s α values between 0.6 and 0.8 are considered acceptable.31 Values greater than 0.8 indicate that there may be redundancy of items in the scale. Cronbach’s α values that are less than 0.6 indicate that items in the scale are not adequately related to one another to measure a concept.31

Validity

Validity is defined as the ability of an instrument to accurately measure a concept of interest. For example, patients who score poorly on the MHQ indicating worse function would be expected to also have poor performance in other aspects of hand functioning, such as strength and dexterity with specific tasks. Three important types of validity exist: content validity, criterion validity, and construct validity.

Content validity, or face validity, describes the extent to which an instrument appears logical or capable of measuring an outcome of interest to experts within a particular field. The MHQ was developed with strict attention to psychometric principles. It has been validated in a variety of acute and chronic hand conditions, and translated into several languages, and therefore is considered appropriate to measure outcomes among RA patients.19,20,16,17,32

Criterion validity describes the extent to which an instrument compares with the accepted reference standard. For patients with RA, there is no established standard to measure health outcomes related to hand dysfunction. Therefore, construct validity is often used to establish the validity of outcomes questionnaires.

Construct validity describes the extent to which the scales in the survey instrument behave as expected. For example, patients who report high pain scores would be expected to endorse difficulty with functioning, ADLs and work performance. We established a priori hypothetical relationships between the scales of the MHQ and used Spearman’s correlation coefficients to test construct validity against each scale of the MHQ. Additionally, we compared responses to the MHQ among SMPA and control patients with their responses to the AIMS2 questionnaire, an existing, validated measure of health status in RA patients, in order to establish the construct validity.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is defined as the ability of an instrument to detect important changes in an outcome of interest over time.33 Because the greatest change after surgery occurs within 6 months after SMPA surgery, we used paired t tests to compare mean scores at baseline and at 6 month follow-up for each scale and for the summary score. In order to compare the change in scores over time using a standardized method, we calculated the standardized response mean (SRM) for each scale of the MHQ. Ideally, a more sensitive instrument should have a higher SRM.34 Using Cohen’s effect size definition, we assumed that an SRM of 0.2 corresponds with a small effect size, 0.5 corresponds with a medium effect size, and 0.8 corresponds with a large effect size.35 The responsiveness of the MHQ was determined separately for SMPA and for control patients.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata 10.1. (Statacorps, College Station, Texas).

Results

The characteristics of the study sample are detailed in Table 1. Of the 160 patients enrolled, 128 patients completed follow-up at 6 months, with a loss to follow up rate of 20%. The majority of the patients were white (97%), female (74%), and right hand dominant (91%) with a mean age of 60.9 years. Approximately 26% had less than a high school education, and 70% earned an annual income of less than $70,000 per year.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 128 patients)

| Patient characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 60.9 years (SD = 9.16) |

| Ethnicity (% White) | 124 (96.9%) |

| Gender (% Female) | 95 (74.2%) |

| Education (% < high school) | 34 (25.6%) |

| Income (% < $50,000 annual) | 87 (70.0%) |

| Right hand dominance | 116 (90.6%) |

| Underwent SMPA | 51 (39.8%) |

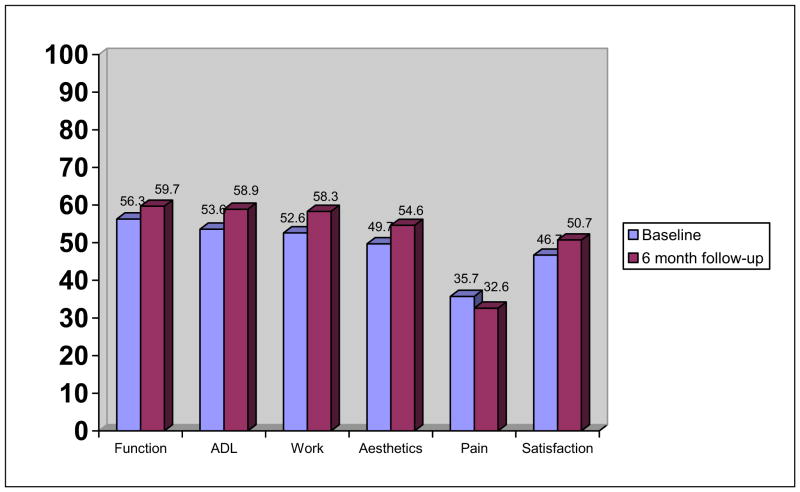

The test-retest reliability of the MHQ was measured by calculating the correlation between responses to the MHQ at baseline, and at 6 months of follow-up (Table 2). Overall, correlations between responses for each time period were high, indicating good reliability of the MHQ. Responses for work performance were most strongly correlated (r=0.72), as well as ability to complete ADLs (r=0.69). Responses regarding pain were the least strongly correlated (r=0.61). The largest difference in scores was noted for ADL (baseline mean: 53.6±2.3, follow-up mean: 58.9 ± 2.4, mean difference = 5.3, p<0.005) and work performance (baseline mean: 52.6 ± 2.2, follow-up mean 58.3 ± 2.5, mean difference = 5.7, p<0.002). Although there were statistically significant differences between scores for each administration, the differences in means were small and unlikely to be clinically relevant.

Table 2.

Test-retest correlation comparing baseline and 6-month follow up scores for the 6 domains of the MHQ (n=128 patients) †

| MHQ Scales | Spearman’s correlation coefficient | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall function | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Activity of Daily Living | 0.69 | <0.001 |

| Work performance | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Aesthetics | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Pain | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| Patient satisfaction | 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Summary MHQ score | 0.66 | <0.001 |

Responses are based on the symptomatic hand for control patients, and on the nonoperated hand for patients who underwent SMPA arthroplasty.

Reliability of the MHQ was also assessed by determining the internal consistency of items within each scale of the MHQ, as measured by Cronbach’s α (Table 3). As described above, the ideal value for Cronbach’s α should lie between 0.6 and 0.8. Cronbach’s α values that are less than 0.6 indicate heterogeneity among items in the scale, and values greater than 0.8 indicate redundancy of items within a scale. For the MHQ, Cronbach’s α scores were within appropriate range for pain (α=0.74, right hand; α=0.66, left hand). Cronbach’s α was high for ADL (α=0.90, right hand; α=0.95, left hand), function (α=0.87, right hand; α=0.88, left hand), aesthetics (α=0.79, right hand; α=0.81, left hand), satisfaction (α=0.89, right hand; α=0.88, left hand), and work performance (α=0.91). These high values may indicate that redundant items exist within the scales of the MHQ.

Table 3.

Internal consistency of the MHQ in RA patients as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (n=128)

| MHQ Scales | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall function | Right hand | 0.87 |

| Left hand | 0.88 | |

| ADL | Right hand | 0.90 |

| Left hand | 0.95 | |

| Both hands | 0.92 | |

| Work performance | 0.91 | |

| Pain | Right hand | 0.74 |

| Left hand | 0.66 | |

| Aesthetics | Right hand | 0.79 |

| Left hand | 0.81 | |

| Patient satisfaction | Right hand | 0.89 |

| Left hand | 0.88 |

To test the construct validity of the MHQ, we tested the responses to each scale against the other scales in the MHQ to determine if each scale behaves in an expected manner using Spearman correlation coefficients (Table 4). For example, we would expect a higher correlation between function and ability to complete ADLs than between aesthetics and ability to complete ADL. For the majority of scales, responses to the MHQ were correlated with the other scales in the expected direction. For example, function was more correlated with ADL (r=0.83), work performance (r=0.65), and pain (r=−0.65) than with aesthetics (r=0.43). As expected, aesthetics was least correlated with work performance (r=0.38). Satisfaction was correlated most strongly with function (r=0.81) and ADL (r=0.83) than with pain (r=−0.69), aesthetics (r=0.41), or work performance (r=0.54).

Table 4.

The correlation between the 6 scales of the MHQ to test the construct validity of the MHQ (n = 128)

| Function | ADL | Work Performance | Aesthetics | Pain | Patient Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | -- | |||||

| ADL | 0.83 | -- | ||||

| Work performance | 0.65 | 0.67 | -- | |||

| Aesthetics | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.38 | -- | ||

| Pain | −0.65 | −0.63 | −0.58 | −0.50 | -- | |

| Satisfaction | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.41 | −0.69 | -- |

To further assess construct validity, we compared responses to each scale of the MHQ with responses to the AIMS2 domains (Table 5). As expected, function (r=−0.63), ADL (r=−0.77), work performance (r=−0.64), pain (r=0.59), and summary MHQ score (r=−0.74) were strongly correlated with the physical domain of the AIMS2 survey. The affect domain of AIMS2 was most strongly correlated with the summary MHQ score (r=−0.53), and the symptom domain of AIMS2 was most strongly correlated with pain (r=0.70). The social domain was not well correlated with any of the MHQ scales. This suggests that the MHQ may not capture some elements of the effect of RA on social interaction and patient affect that are measured by the AIMS2.

Table 5.

The correlation of the 6 scales of the MHQ with the AIMS2 domains (N = 128)

| Physical | Affect | Symptom | Social | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | −0.63 | −0.41 | −0.48 | −0.23 |

| ADL | −0.77 | −0.47 | −0.50 | −0.28 |

| Work performance | −0.64 | −0.47 | −0.55 | −0.33 |

| Aesthetics | −0.38 | −0.36 | −0.35 | −0.20 |

| Pain | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.27 |

| Patient satisfaction | −0.54 | −0.42 | −0.49 | −0.24 |

| Summary MHQ score | −0.74 | −0.53 | −0.63 | −0.32 |

We calculated the responsiveness of the MHQ to detect clinical change in hand function over the 6 month study period. The summary MHQ score and scores for each scale of the MHQ at baseline and at 6 month follow-up and the SRM for each scale of the MHQ are given in Table 7. As expected, the MHQ demonstrated strong responsiveness to clinical change in the group of patients who underwent SMPA. SRMs were high for function (SRM=1.42), ADL (SRM=0.89), aesthetic appearance (SRM=1.23), satisfaction (SRM=1.76), and the summary MHQ score (SRM=1.61). Responsiveness was lower for pain (SRM=0.63) and work performance (SRM=0.47). With respect to the control patients, changes for all measures over a 6 month time period were modest, and there were no statistically significant differences between mean scores for any measure. Work performance was the most responsive measure over time (SRM=0.14), although this is overall a very low effect. Because these patients did not undergo surgical reconstruction, we would not expect to see a large change in their hand performance during this brief period of time.

Discussion

The Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ) is a hand-specific outcome measurement tool that has been extensively studied in a variety of acute and chronic hand conditions including nerve compression, distal radius fractures, Dupuytren’s disease, and osteoarthritis.15–20 The MHQ is ideal for use in the rheumatoid arthritis population, because it specifically encompasses measures of aesthetics and pain control, which have been shown to be important motivators for surgical therapy among RA patients.36, 37

The MHQ demonstrated good test-retest reliability, with minimal change in scores between survey administrations. Overall, the six scales of the MHQ demonstrated excellent internal consistency, although item redundancy exists within the MHQ domains. This indicates that the MHQ may be well-suited for item reduction in the future, which may improve response rates by shortening the time to complete the survey. The ADL, work performance, and pain scales of the MHQ were correlated in the expected direction with the AIMS2 instrument, particularly with respect to the physical domain. Finally, the MHQ showed excellent responsiveness among patients who underwent SMPA arthroplasty and was able to detect change in hand performance over a 6 month time period. As expected, changes in hand performance as measured by the MHQ among patient who had not undergone surgery were modest over the 6-month follow-up period.

Other methods for assessing the extent of disability related to rheumatoid hand disease include describing the extent of anatomic deformity using scoring algorithms based on clinical examination or radiographic evidence of joint destruction. For example, the Hand Index uses simple hand measurements of the span and lateral height of the open and closed hand to create a standardized measure of deformity.38 The Joint Alignment and Motion (JAM) score and the mechanical joint score can be used to define hand deformity and dysfunction at the bedside, but are subject to observer variation.39,40 Radiographic evidence of disease and disease progression have been defined by other instruments, such as the Sharp Index.41 These measures have the advantage of documenting the progression of disease over time, but do not adequately predict the clinical manifestations of disease such as pain, occupational disability, and the need for joint replacement.42 Although describing anatomic deformity may be helpful as part of a global assessment of disability, it is problematic when taken alone because many patients are able to retain excellent hand functioning despite deformity. Pain, joint instability, and exercise tolerance are more predictive of physical functioning and general health perception among RA patients than clinical or radiologic joint appearance.8, 43

The MHQ is the first self-administered instrument validated in rheumatoid arthritis patients that comprehensively gathers information on functional ability and the ability to complete daily and occupational activities, as well as patient satisfaction, pain and aesthetic hand appearance. It is the only questionnaire validated in this population that can adjust for hand dominance, and the differences in hand disability between both hands. Several upper-extremity specific instruments have been used to measure hand function in rheumatoid patients. The Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire has been used to study rheumatoid patients, but its validity and responsiveness have not been documented in this population.44 Furthermore, it does not make a distinction between right and left hand disability, and focuses on the entire upper limb, not specifically hand dysfunction. The Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation Questionnaire (PRWE) has been used to study pain and function among rheumatoid arthritis patients, but focuses primarily on wrist, not hand dysfunction, with frequently co-exist in rheumatoid patients.45 The Cochin Rheumatoid Hand Disability scale has been developed to measure the effectiveness of surgery on rheumatoid hand functioning with respect to activities of daily living, and has been shown to be valid in this population and sensitive to changes in disease state.46, 47 It does not, however, include important aspects of the patient experience including an assessment of pain, patient satisfaction or aesthetics.47, 48

Our findings are consistent with previous, smaller studies regarding the use of the MHQ to describe hand disability among RA patients. In comparison with the Australian Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index (AUSCAN), and the Sequential Occupational Dexterity Assessment (SODA), the MHQ yields reproducible results, and is uniquely suited to measure outcomes in RA patients because it can discern disability in both hands.24 Although the MHQ was less responsive to clinical change among control patients because expectedly the control patients should not have changes in hand performance, it demonstrated excellent responsiveness among patients undergoing SMPA. These results are consistent with prior work using the MHQ to measure outcomes in Dutch patients with RA. In this study, the MHQ demonstrated excellent responsiveness to clinical change over time, particularly in the domains of patient satisfaction and hand aesthetics.22

Our study has several notable limitations. First, criterion validity cannot be assessed because there is no previously accepted “gold standard” instrument for measuring hand function among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Additionally, the progression of rheumatoid hand dysfunction may be too slow to detect appreciable clinical change, and longer follow-up may be needed to understand the MHQ’s responsiveness to change in patients who have not undergone surgery. However, we were able to demonstrate excellent responsiveness among patients who underwent surgical intervention. Finally, our sample size prevented us from stratifying our results based on disease severity and effects of medical and occupational therapies, which may have influenced our results.

Nonetheless, this study demonstrates that the MHQ is an essential instrument to understand the extent of disability of rheumatoid hand disease. The MHQ offers clinicians a systematic approach to defining patient disability. Additionally, the MHQ can be incorporated into future studies regarding the effectiveness of RA therapies as it offers a comprehensive assessment of hand functioning and patient-centered outcomes. In conclusion, the MHQ is an easily administered, reliable, valid tool to measure rheumatoid hand function, and an essential instrument to systematically guide clinical decision making and assess the quality of care of rheumatoid hand disease.

Figure 1.

Table 6.

Responsiveness of the MHQ to clinical change over 6 month follow-up period

| Mean baseline mean± SD | Mean 6 month mean ± SD | p value♣ | SRM* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMPA patients (n=51) | ||||

| MHQ Summary Score | 38.3 ± 18.4 | 62.7 ± 20.8 | <0.0001 | 1.61 |

| Function | 37.6 ± 23.0 | 65.2 ± 20.3 | <0.0001 | 1.42 |

| ADL | 36.6 ± 27.4 | 55.9 ± 29.4 | <0.0001 | 0.89 |

| Work performance | 41.9 ± 23.0 | 52.3 ± 29.1 | 0.002 | 0.47 |

| Pain | 48.2 ± 26.3 | 33.4 ± 24.9 | <0.0001 | 0.63 |

| Aesthetics | 34.3 ± 22.4 | 71.0 ± 23.5 | <0.0001 | 1.23 |

| Satisfaction | 27.6 ± 20.2 | 65.6 ± 25.0 | <0.0001 | 1.76 |

| Controls (n=77) | ||||

| MHQ Summary Score | 56.8 ± 19.0 | 58.3 ± 20.2 | 0.40 | 0.10 |

| Function | 59.5 ± 18.8 | 59.2 ± 21.2 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| ADL | 59.8 ± 23.5 | 60.3 ± 25.9 | 0.83 | 0.02 |

| Work performance | 59.7 ± 22.9 | 62.3 ± 27.6 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| Pain | 35.2 ± 25.6 | 32.5 ± 26.0 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Aesthetics | 49.2 ± 24.8 | 51.3 ± 23.1 | 0.32 | 0.11 |

| Satisfaction | 48.3 ± 25.8 | 49.0 ± 26.2 | 0.77 | 0.03 |

Paired t-test comparing 6-months to baseline.

Standardized Response Mean is calculated using the following formula: (6-months follow-up mean − baseline mean) / standard deviation of the change

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR047328) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

References

- 1.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherrer YS, Bloch DA, Mitchell DM, Young DY, Fries JF. The development of disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:494–500. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward MM, Javitz HS, Yelin EH. The direct cost of rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health. 2000;3:243–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2000.34001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellhag B, Bjelle A. A Grip Ability Test for use in rheumatology practice. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1559–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jebsen RH, Taylor N, Trieschmann RB, Trotter MJ, Howard LA. An objective and standardized test of hand function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1969;50:311–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backman C, Mackie H. Arthritis hand function test: inter-rater reliability among self-trained raters. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:10–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pap G, Angst F, Herren D, Schwyzer HK, Simmen BR. Evaluation of wrist and hand handicap and postoperative outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clin. 2003;19:471–81. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(03)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman MJ. Patient questionnaires in rheumatoid arthritis: advantages and limitations as a quantitative, standardized scientific medical history. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:735–43. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalyoncu U, Dougados M, Daures JP, Gossec L. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in recent trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:183–90. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boers M, Felson DT. Clinical measures in rheumatoid arthritis: which are most useful in assessing patients? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1773–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boers M, Tugwell P, Felson DT, et al. World Health Organization and International League of Associations for Rheumatology core endpoints for symptom modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1994;41:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandl LA, Burke FD, Shaw Wilgis EF, Lyman S, Katz JN, Chung KC. Could preoperative preferences and expectations influence surgical decision making? Rheumatoid arthritis patients contemplating metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:175–80. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000295376.70930.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavaliere CM, Chung KC. Total wrist arthroplasty and total wrist arthrodesis in rheumatoid arthritis: a decision analysis from the hand surgeons’ perspective. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1744–55. 55 e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung KC, Squitieri L, Kim HM. Comparative outcomes study using the volar locking plating system for distal radius fractures in both young adults and adults older than 60 years. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:809–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung KC, Ram AN, Shauver MJ. Outcomes of pyrolytic carbon arthroplasty for the proximal interphalangeal joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1521–32. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a2059b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sammer DM, Fuller DS, Kim HM, Chung KC. A comparative study of fragment-specific versus volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1441–50. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181891677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herweijer H, Dijkstra PU, Nicolai JP, Van der Sluis CK. Postoperative hand therapy in Dupuytren’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1736–41. doi: 10.1080/09638280601125106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein RD, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Open carpal tunnel release using a 1-centimeter incision: technique and outcomes for 104 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1616–22. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000057970.87632.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang EY, Chung KC. Outcomes of trapeziectomy with a modified abductor pollicis longus suspension arthroplasty for the treatment of thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:505–15. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817d5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams J, Burridge J, Mullee M, Hammond A, Cooper C. The clinical effectiveness of static resting splints in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1548–53. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Giesen FJ, Nelissen RG, Arendzen JH, de Jong Z, Wolterbeek R, Vliet Vlieland TP. Responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire--Dutch language version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandl LA, Galvin DH, Bosch JP, et al. Metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: what determines satisfaction with surgery? J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2488–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massy-Westropp N, Krishnan J, Ahern M. Comparing the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index, Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire, and Sequential Occupational Dexterity Assessment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1996–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldfarb CA, Stern PJ. Metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. A long-term assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1869–78. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM. A prospective outcomes study of Swanson metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty for the rheumatoid hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung KC, Burns PB, Wilgis EF, et al. A multicenter clinical trial in rheumatoid arthritis comparing silicone metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty with medical treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:815–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. AIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma S, Schumacher HR, Jr, McLellan AT. Evaluation of the Jebsen hand function test for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [corrected] Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:16–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trochim W, Donnelly JP. The Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2. Cincinnati, Ohio: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Streiner DL, Norman GR, editors. Health Measurement Scales: A practical guide to their development and use. New York, New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, Hayward RA. Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23:575–87. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung KC, Hamill JB, Walters MR, Hayward RA. The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ): assessment of responsiveness to clinical change. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:619–22. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang MH, Lew RA, Stucki G, Fortin PR, Daltroy L. Measuring clinically important changes with patient-oriented questionnaires. Med Care. 2002;40:II45–51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J, editor. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alderman AK, Arora AS, Kuhn L, Wei Y, Chung KC. An analysis of women’s and men’s surgical priorities and willingness to have rheumatoid hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM, Burke FD, Wilgis EF. Reasons why rheumatoid arthritis patients seek surgical treatment for hand deformities. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Highton J, Markham V, Doyle TC, Davidson PL. Clinical characteristics of an anatomical hand index measured in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as a potential outcome measure. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:651–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson AH, Hassell AB, Jones PW, Mattey DL, Saklatvala J, Dawes PT. The mechanical joint score: a new clinical index of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:189–95. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiegel TM, Spiegel JS, Paulus HE. The joint alignment and motion scale: a simple measure of joint deformity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:887–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharp JT. Scoring radiographic abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:568–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yazici Y, Sokka T, Pincus T. Radiographic measures to assess patients with rheumatoid arthritis: advantages and limitations. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:723–9. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eurenius E, Brodin N, Lindblad S, Opava CH. Predicting physical activity and general health perception among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk V, Bombardier C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14:128–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS, Beadle M, Roth JH. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:577–86. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duruoz MT, Poiraudeau S, Fermanian J, et al. Development and validation of a rheumatoid hand functional disability scale that assesses functional handicap. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poiraudeau S, Lefevre-Colau MM, Fermanian J, Revel M. The ability of the Cochin rheumatoid arthritis hand functional scale to detect change during the course of disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:296–303. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)13:5<296::aid-anr9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lefevre-Colau MM, Poiraudeau S, Fermanian J, et al. Responsiveness of the Cochin rheumatoid hand disability scale after surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:843–50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.8.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]