Abstract

Correct localization of membrane proteins is essential to all cells. Chaperone cascades coordinate the capture and handover of substrate proteins from the ribosome to their target membrane; yet the mechanistic and structural details of these processes remain unclear. Here we investigate the conserved GET pathway, in which the Get4-Get5 complex mediates the handover of tail-anchor (TA) substrates from the co-chaperone Sgt2 to the Get3 ATPase, the central targeting factor. We present a crystal structure of a yeast Get3-Get4-Get5 complex in an ATP-bound state, and show how Get4 primes Get3 into the optimal configuration for substrate capture. Structure-guided biochemical analyses demonstrate that Get4-mediated regulation of ATP hydrolysis by Get3 is essential to efficient TA protein targeting. Analogous regulation of other chaperones or targeting factors could provide a general mechanism for ensuring effective substrate capture during protein biogenesis.

Keywords: Tail-anchor targeting, GET pathway, protein transport, X-ray crystallography

In eukaryotes, the proper targeting of membrane proteins is a significant challenge for the cell to overcome 1. Integral membrane proteins contain hydrophobic transmembrane domains (TMD), which must be protected from the aqueous cytosolic environment prior to integration into the appropriate membrane. For the majority of membrane proteins targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), this is accomplished by the signal recognition particle (SRP), typically binding the initial TMD, or signal anchor, as it emerges from the ribosome and targets it to the ER for co-translational insertion. Exceptions are the ubiquitous tail-anchor (TA) proteins, defined topologically by a single transmembrane domain near the C-terminus, which are unable to access the SRP pathway and must be targeted to the ER post-translationally 2,3.

Found in most cellular membranes, TA proteins are targeted to either the ER or mitochondria. For the latter, a dedicated pathway has not been identified 4. Those destined for other organelles are initially targeted to the ER, and then subsequently trafficked to the appropriate membrane 3. Examples include many essential proteins such as SNAREs (vesicle fusion), Bcl-2 (apoptosis), and Sec61γ (protein translocation machinery) 5. A need for specific targeting of ER destined TA proteins was first conceptualized nearly two decades ago 2 and the cellular factors responsible have now been identified. The central targeting factor was identified biochemically in a mammalian system as the cytosolic ATPase TRC40, demonstrated to bind the TA and deliver it specifically to the ER 6,7. Previous genetic experiments involving the yeast homolog, Get3, could then be linked to TA targeting providing a route for studying this process 8. This was followed by a series of results that characterized the new pathway, termed GET (Guided Entry of TA proteins) 9–11. In yeast, this pathway consists of six proteins, Get1-5 and Sgt2, all with homologs in higher eukaryotes (Reviewed in Ref. 12).

Structural characterization of Get3, the central TA targeting factor, demonstrates that it undergoes ATP-dependent conformational changes from a apo ‘open’ to an ATP-bound ‘closed’ form required for capturing the TA substrate 12–18. Deletion of Get3 in yeast leads to a buildup of mislocalized cytosolic TA proteins 9 and is embryonic lethal in mice 19. The Get3-TA complex is recruited to the ER by the membrane proteins Get1-Get2 (Get1-2) 20–23. These stimulate release of the TA protein and subsequent insertion into the ER membrane, although the specifics of this mechanism are, as yet, unknown. Upstream of Get3 is the multi-domain Hsp70 or Hsp90 co-chaperone Sgt2 11,24,25 that specifically binds the TA, the first committed step in TA targeting, followed by hand-over to Get3 24.

Efficient delivery of a TA substrate to Get3 requires the hetero-tetrameric Get4-Get5 (Get4-5) complex that provides the link between Sgt2 and Get3 11,24,26. Structural studies of Get4 and the N-terminal domain of Get5, also called Mdy2, revealed that Get4 is an alpha-helical repeat protein, with the N-terminus of Get5 wrapping around its C-terminus 27,28. Biochemical and genetic evidence implicated the N-terminal face of Get4 in Get3 binding at an interface that shared commonalities with the binding sites for Get1 and Get2 27,28. In SAXS reconstructions, the full-length Get4-5 complex forms an extended structure where Get4 flanks the Get5 ubiquitin-like domain (Ubl) and central Get5 C-terminal homodimerization domain 25,27,29. Initial results suggested that binding of Get4 to Get3 required nucleotide 27; however, a subsequent publication has brought this into question 30. More recent work has expanded on the role of Get4-5 in TA targeting beyond acting as a simple bridge. In addition to preferentially recognizing a nucleotide bound Get3, Get4 inhibits Get3 ATP hydrolysis 31. TA binding is the presumptive trigger for hydrolysis 31, thus Get4 helps to stabilize Get3 in a conformation competent for TA binding. Since a major outstanding question is how Get4 regulates Get3 activity, we set out to understand the structural basis of Get4 function.

This report describes the 5.4 Å crystal structure of an ATP-bound Get3-Get4-5 complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc), a combined ~160 kDa hetero-hexameric structure. Two functionally distinct binding interfaces for anchoring and ATPase regulation were found between Get3 and Get4, that were confirmed biochemically and genetically. Mutations at these interfaces demonstrated that Get4-5-mediated regulation of ATP hydrolysis by Get3 were critical for efficient TA targeting. Finally, crystallographic tetramers of Get3 are compatible with two Get3 dimers bridged by a single Get4-5 hetero-tetramer. In total, this work illustrates how Get4-5 regulates Get3, priming it for TA loading, a critical step in this important pathway.

RESULTS

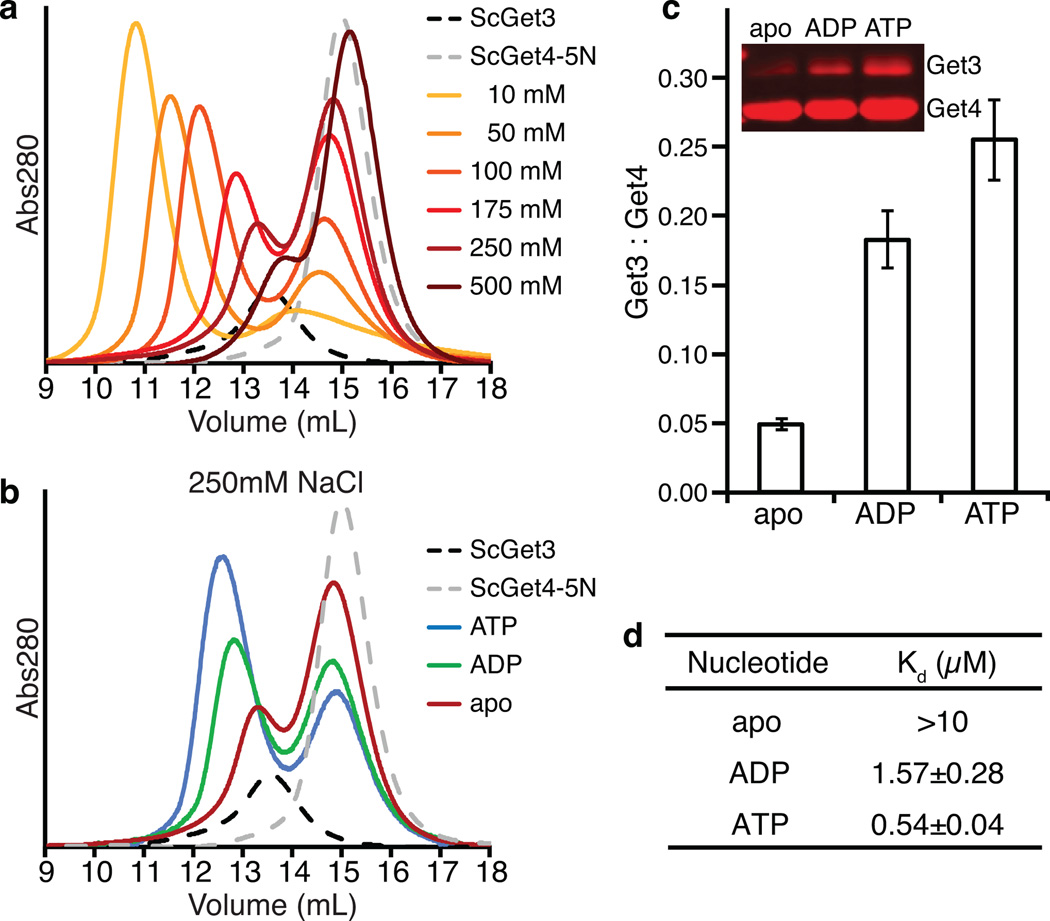

Get4-5 binds the ATP-bound state of Get3

It was first important to establish the requirements for forming a stable Get3-Get4-5 complex. Unless noted, Get3 is either wild type or contains an ATPase inactivating mutation (D57V, referred to as Get3D) that prevents ATP hydrolysis while still allowing ATP binding. Get4-5 is either the wild-type hetero-tetramer (Get4-5) or a 22 residue C-terminal truncation of Get4 (1–290) and the 54 residue N-terminal domain of Get5 (Get4-5N), similar to that used in a crystal structure of the heterodimer 27. As observed previously 30, in low salt (10 mM NaCl) a 1:1 complex of Get3D bound to Get4-5N could be generated that was stable by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Fig. 1a, yellow trace). Increasing the salt concentration resulted in a loss of complex formation such that no complex could be detected at 500 mM NaCl (brown trace), suggesting an electrostatic interaction. At near physiological conditions (175 mM NaCl), a complex between Get3D-Get4-5 was disfavored (dark red trace) suggesting that additional factors were required to stabilize the complex in vivo.

Figure 1. Get4-5 prefers ATP-bound state of Get3.

(a) SEC of Get3D-Get4-5N run in various salt concentrations. (b) SEC of Get3D-Get4-5N in 250 mM NaCl. (c) Pulldown experiments using 6×His-tagged Get4-5N and Get3D. The amount of Get3D retained after elution is plotted as a fraction of Get4, and error bars represent the s.d. from n=3 technical replicates. (d) Summary of the binding affinities of Get4-5N to Get3D obtained by ITC experiments. Data is expressed as Kd (µM) with n = at least 3 technical replicates.

Based on previous evidence that suggested a role for nucleotide in complex formation 27, a variety of assays were tested to confirm nucleotide stabilization of the Get3D-Get4-5N complex. SEC was performed in the presence of nucleotide at a salt concentration where the complex was disfavored (250 mM NaCl) (Fig. 1a,b, orange trace). For ADP, a clear stabilization of the complex was seen (Fig. 1b, green trace) while ATP resulted in the most stable complex (blue trace), consistent with previous experiments 27,31. Additionally, pull-down experiments were quantified where tagged Get4-5N was used to precipitate Get3D with binding presented as a ratio of the two. These experiments confirmed the nucleotide-dependence as observed with SEC demonstrating a preference for ATP (Fig. 1c). Finally, affinity constants (Kd) were measured using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) at a physiological ionic strength (150 mM KOAc) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1). For an apo-Get3D, a Kd could not be measured suggesting that the affinity was less than 10 µM. In the presence of ADP, Get4-5N binds to Get3 with micromolar affinity that increases to ~500 nM with ATP. Collectively, all three assays show that Get4-5 preferentially interacts with ATP-bound Get3 at physiological ionic strength conditions.

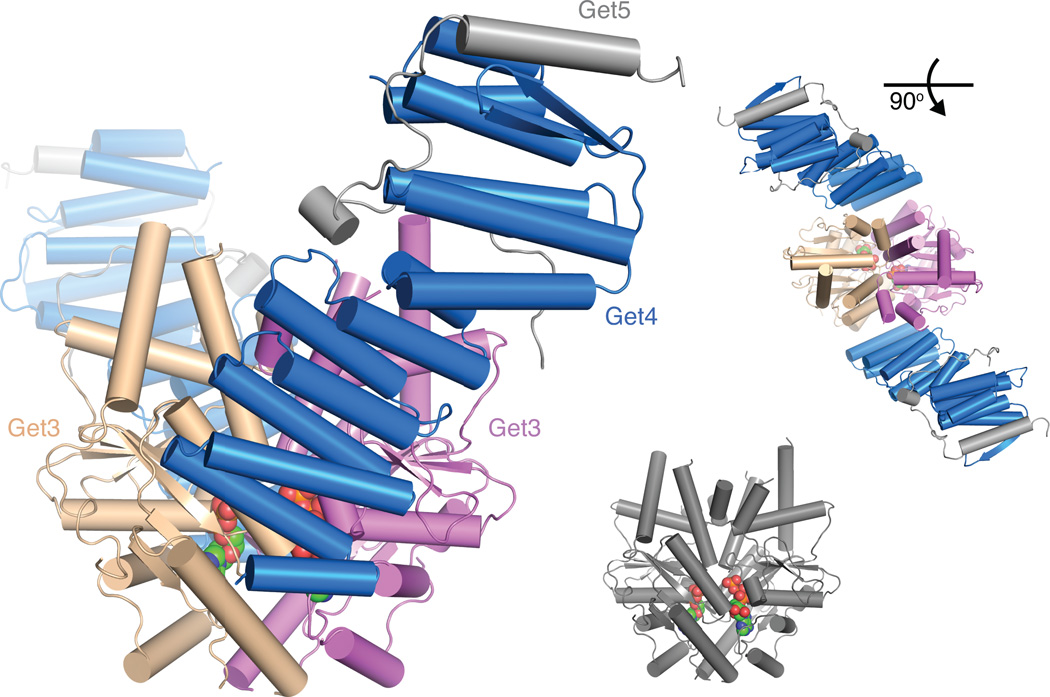

Architecture of the Get3-Get4-5 complex

While it is clear that Get4 recognizes the ATP-bound state of Get3, the structural details of this interaction were missing. To understand these, a complex of ATP, Get3D and Get4-5N was crystallized and a structure was determined to 5.4 Å resolution (Table 1). In the structure, there is a 1:1 ratio of Get3D to Get4-5N. Get3 is in a ‘closed’ conformation, as anticipated based on ATP being bound 14, with the Get4 interaction lying across the dimer interface (Fig. 2). An ‘anchoring’ (see below) interface (primarily to the brown Get3 in the figure) buries ~920 Å2 surface area, while a ‘regulatory’ interface (primarily to the purple Get3) contributes ~400 Å2 to this interaction (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics (molecular replacement)

| SSRL BL12-21 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C 2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 166.3, 134.5, 84.1 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 113.4, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0-5.4 (6.0-5.4)2 |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.05 (0.46) |

| I / σI | 7.4 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.8 (95.9) |

| Redundancy | 0.05 (0.46) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0-5.4 (6.0-5.4) |

| No. reflections | 5,529 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 0.270/0.328 |

| No. atoms | 10,177 |

| Protein | 10,112 |

| Ligand/ion | 65 |

| Water | n/a |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 348.5 |

| Ligand/ion | 317.4 |

| Water | n/a |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0032 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.94 |

A single native crystal was used to determine the structure Get3D–Get4–Get5

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

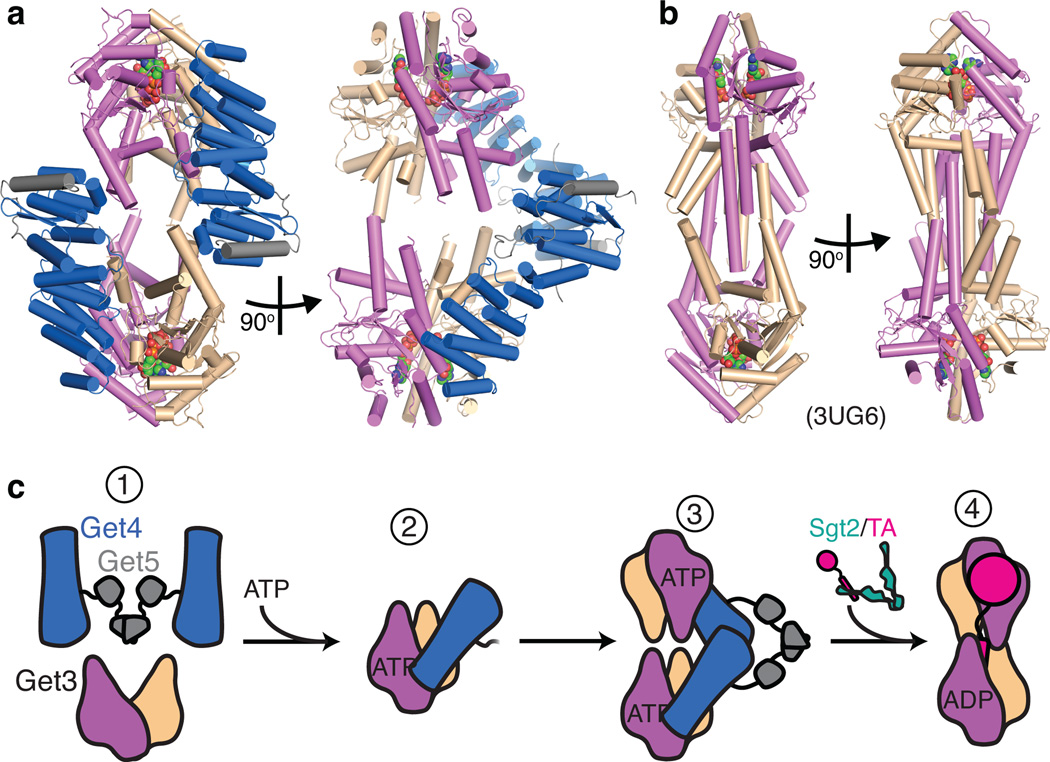

Figure 2. 5.4 Å crystal structure of an ATP-bound Get3-Get4-5 complex.

The asymmetric unit of the Get3D-Get4-5N complex in two orientations (Get4 blue and Get5N gray) bound to Get3D (wheat and magenta). Bottom right, Get3D dimer alone in gray to emphasize the ‘closed’ structure. ATP is represented as spheres.

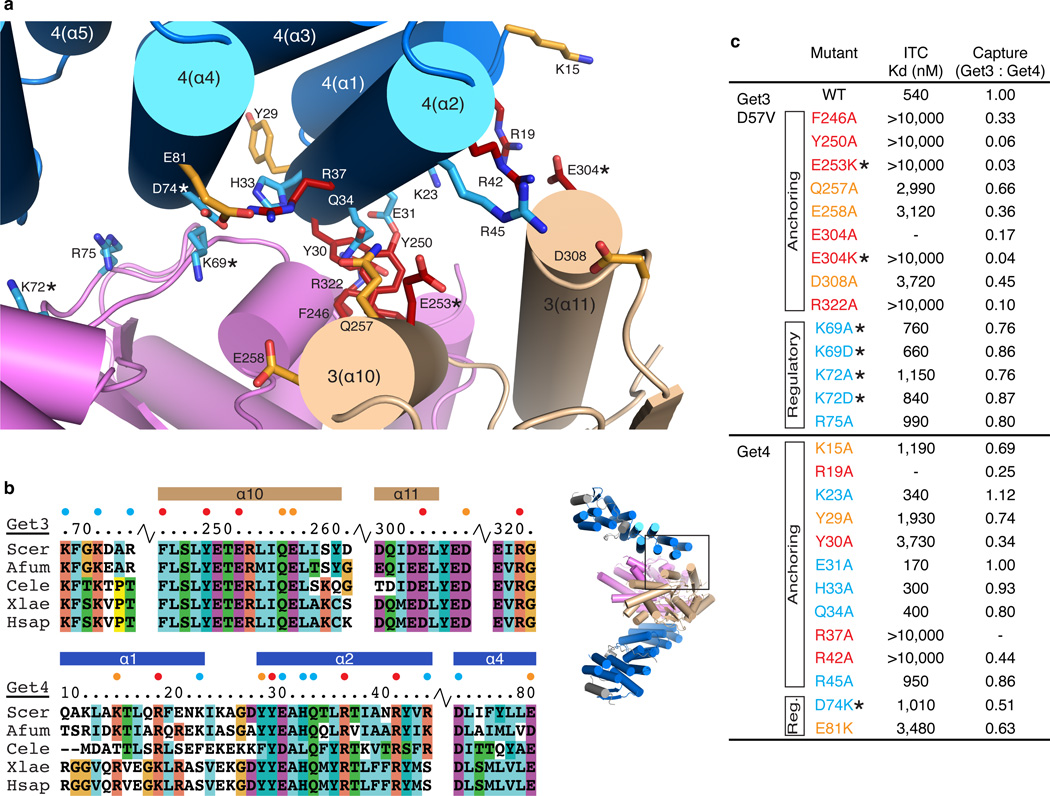

At the anchoring interface, Get4 α2 makes extensive contacts roughly parallel to the groove formed by Get3 α10 and α11 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3, we have included side-chains for clarity despite the resolution). This results in an interaction between the invariant residues Phe246 and Tyr250 on Get3 α10 and Tyr30 on Get4 α2 (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). In addition to these hydrophobic contacts, a number of highly conserved charged residues are located within this interface (Get3: Glu253, Gln257, Glu258, Glu304, Asp308 and Get4: Arg37, Arg42). In contrast to α2, Get4 α1 is located on the opposite face relative to Get3, and makes fewer contacts. However, the N-terminus of Get4 α1 is tilted toward Get3 placing the conserved charged residues Lys15 and Arg19 in close proximity to Get3 α10. Previously, this group had demonstrated that residues on the N-terminal face of Get4 bound Get3 residues at a similar surface to that demonstrated for the ER receptors Get1 and Get2 20,21,27. A number of these residues map to the anchoring interface (Get3: Tyr250, Glu253 and Get4: Arg19, Tyr30, Arg37, Arg42) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Figure 3. Get3-Get4 binding interfaces.

(a) View of the Get3-Get4 interface showing interactions between Get4 (blue) and both monomers of Get3D (wheat and purple). Residues at the interface tested for interaction are shown as sticks and colored based on phenotype. The positions of side chains cannot be determined at this resolution and are only shown here for reference. Below, overview of Get3D-Get4-5N in same orientation used to show the interface. Area within the box represents the interface shown above. (b) Sequence alignments of regions involved in contacts in the Get3-Get4 interface and colored based on ClustalW output 34. Sequences are: Scer – S. cerevisiae, Afum – Aspergillus fumigatus, Cele – Caenorhabditis elegans, Xlae – Xenopus laevis and Hsap – Homo sapiens. Helices are indicated above the sequence and labeled. Residues tested are highlighted by spheres and colored based on phenotype (blue, none or minimal; orange, moderate; red, strong). (c) Summary of the data obtained by ITC and pulldown experiments. Mutants are colored based on strength of phenotype as in (a-b). ITC data was generated from a single experiment; pulldown experiments were performed in triplicate, with the mean shown.

At the regulatory interface, located on the opposing monomer, the C-terminal end of Get4 α4 packs against the loop following Get3 α3 (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3). This places a number of highly conserved complementary charged residues within this interface (Get3: Lys69, Lys72, Arg75 and Get4: Asp74, Glu81). Central to this interaction are the invariant residues Lys69 (Get3) and Asp74 (Get4), which are located opposite one another.

Mutational analysis of the Get3–Get4 interface

As noted above, the extensive Get3–Get4 interface involves varied contacts to both monomers. ITC and affinity capture assays were performed to determine which residues are essential for binding (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). As expected, alanine substitution of the invariant hydrophobic residues (Get3: Phe246, Tyr250 and Get4: Tyr30) dramatically reduced the binding affinity. In addition, a number of the conserved charged residues within the anchoring interface (Get3: Glu253, Glu304 and Get4: Arg19, Arg37, Arg42) produced similar effects following their substitution. A moderate binding defect was seen with Ala substitutions of the remaining residues on Get3 α10 (Gln257, Glu258) and the loop following Get3 α11 (Asp308). Substitution of the remaining residues on Get4 (Get4: Lys15, Lys23, Tyr29, Glu31, His33, Gln34, Arg45), which are located farther away from the core of the anchoring interface and of lower sequence conservation, had little to no effect on binding.

At the regulatory interface, several highly conserved basic residues in Get3 (Lys69, Lys72, Arg75) are in close proximity to oppositely charged residues in Get4 (Asp74, Glu81). Nevertheless, substitution of these Get3 residues by Ala or Asp has little to no effect on Get4 binding (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, substitution of Get4 Asp74 by Lys resulted in a marginal increase in Kd ~1 µM as determined by ITC (Fig. 3c). Collectively, these studies revealed that the anchoring interface is mainly responsible for the specificity of binding between Get3 and Get4.

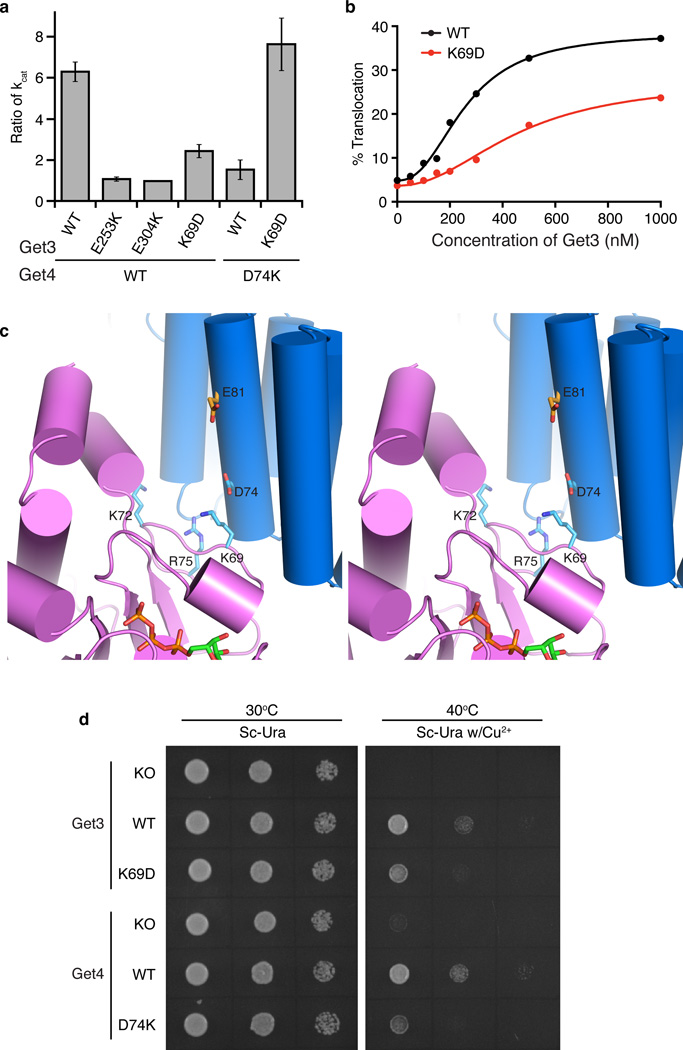

Regulation of Get3 nucleotide hydrolysis

While the regulatory interface is not involved largely in binding, the highly conserved nature of residues at this interface suggests they play an alternative role in TA targeting. Recently published work demonstrated that Get4-5 binding results in inhibition of Get3 ATP hydrolysis 31. To test if this interface plays a role, kcat was determined for several mutants of Get3 in the absence and presence of Get4–5 (Supplementary Table 1). The results are presented as a ratio (-Get4-5:+Get4-5) where a larger number indicates inhibition by Get4-5, e.g. wild-type Get4-5 inhibits Get3 ~6-fold (Fig. 4a). Consistent with their binding defects, the Get3 mutants E253K and E304K were not inhibited by Get4-5 (Fig. 4a). Notably, Get3 K69D, situated at the regulatory interface, significantly lost the ability to be inhibited by Get4-5 (Fig. 4a) although it bound Get4-5 with similar affinities to wild type (Fig. 3c). A Get3 K72D mutant also lost the ability to be inhibited by Get4–5 relative to wild-type, albeit to a smaller extent (Supplementary Table 1). Mutation of the invariant Get4 Asp74, situated opposite Get3 Lys69 (Fig. 3b and 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2b,c and 3), yielded the same phenotype (Fig. 3c and Fig. 4a). Importantly, combining both opposing mutants (Get3 K69D/Get4 D74K) restored the ability of Get4–5 to regulate Get3 ATPase activity, demonstrating that these two residues directly interact (Fig. 4a). This is again consistent with the high conservation of residues located on either side of this interface (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). These results demonstrate that Get4 plays two distinct roles for Get3, recruitment and regulation, which can be biochemically decoupled.

Figure 4. Get4-5 regulates Get3 ATPase activity.

(a) Get3 ATPase assay in the presence and absence of Get4-5 and mutants. The Get4-5 effect is represented as a ratio of kcat in the absence and presence of Get4-5, with a value of 1 indicating no inhibition by Get4-5. The values are shown as means and standard variations for ratios calculated from n independent trials (Supplementary Table 1). (b) Comparison of Get3 translocation efficiency between wt and K69D. (c) Stereo view of the regulatory interface showing interactions between Get4 (blue) and Get3 (purple). (d) Spot plate growth assays of pRS316 derived rescue plasmids under control of genetic promoters in the BY4741 Get3::KanMx or Get4::KanMx background. “KO” represents transformation with empty vector. Plates consisted of Sc-Ura with or without 2 mM CuSO4. Each image was taken from a single plate at either 24 h (30°C, Sc-Ura) or 48 h (40°C, Sc-Ura w/2 mM CuSO4).

To test whether the regulation of Get3 ATPase activity is important for TA targeting, a reconstituted in vitro targeting assay was used 31. Specifically, a TA-substrate, Sbh1, was translated in Δget3 yeast extracts and targeted to ER microsomes by exogenously added Get3. The efficiency of targeting is then reported by the glycosylation of an engineered opsin tag on Sbh1 upon insertion into microsomes. Mutant Get3 K69D exhibits a ~40% loss of Sbh1 insertion compared to wild-type, which agrees with its loss in Get4-5-induced regulation of ATPase activity (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Importantly, this effect is only seen in the presence of Get4-5 as both wild-type Get3 and Get3 K69D have the same targeting efficiency using translation extracts from a Δget3/Δmdy2 strain (Get4 is depleted in this strain24) (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). This is distinct from Get1-2 binding mutants as the critical E253K mutant (that cannot bind Get1 or Get2) 20–22 completely abolishes insertion in both Δget3 and Δget3/Δmdy2 extracts (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c), which demonstrates that the Get3 K69D mutant does not directly affect the membrane-associated steps. The formation of functional Get3-TA complexes likely follows a mechanism similar to wild-type in these mutants, as the data still fits a Hill coefficient of 2, previously shown to correlate with Get3 tetramer formation 31. In addition, the targeting by Get3 K69D cannot be rescued by increasing protein concentration (Fig. 4b), consistent with a model in which premature ATP hydrolysis in this mutant reduces the fraction of productive Get3-Get4-5 complexes that can capture and target the TA substrate. Thus, Get4-5-induced delay of ATP hydrolysis from Get3 is integral for ensuring efficient TA protein targeting.

To examine whether this regulation is important for Get3 function in vivo, the ability of Get3 K69D and Get4 D74K to rescue known knockout phenotypes was tested using a yeast growth assay 9,13,27. As before, neither the Δget3 nor Δget4 strains showed a phenotype when grown on synthetic complete media at 30°C. However, growing these strains at 40°C in the presence of 2mM Cu2+ produced a strong phenotype that could be rescued by expression of the wild-type protein on a plasmid (Fig. 4d). A Get3 K69D mutant was unable to fully rescue the growth phenotype supporting a role for regulation in vivo. A Get4 D74K mutant was also unable to fully rescue resulting in an even stronger phenotype than the Get3 K69D mutant (Fig. 4d). It is important to note that this surface of Get4 has no other known interacting partners meaning that this phenotype can only be readout of the regulatory role of Get4. In total, these results provide strong evidence that Get4-5-mediated regulation of Get3 ATPase activity is critical for a functional GET pathway.

DISCUSSION

The structure of the Get3-Get4-5 complex presented here reveals the molecular basis of Get3 recognition by Get4. In particular, the structure provides insight into the role of nucleotide in complex formation, where Get4 binds to both monomers of Get3 in an orientation only compatible with a closed Get3. The anchoring interface was demonstrated to mediate the interaction between Get3-Get4, while the regulatory interface is critical for inhibition of Get3 ATP activity. This regulation of Get3 is necessary for efficient targeting in vitro and loss of regulation leads to growth defects in vivo. While it is difficult to speculate at sub-atomic resolution, it is interesting to note that Get3 Lys69 connects through a short helix to the critical Switch I loop that contains the catalytic D57. This would make the interaction between Get4 Asp74 and Get3 Lys69 allosteric leading to inactivating conformational changes in the catalytic pocket.

There is growing evidence that the soluble Get3-TA complex contains a tetramer of Get3, in which two copies of the dimer form a hydrophobic chamber 18,31. A tetramer of Get3 is observed in the Get3-Get4-5 crystal packing that is strikingly similar to the tetramer structures seen in the archaeal Get3 homolog 19 and in the crystal packing of the Get2-Get3 complex 16 (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5). If one considers the orientations of the Get4 monomers across the tetramer, the distances are compatible with the requirement that they be bridged by the rest of the Get5 dimer (Fig. 5a) 25. In contrast, while a Get3 dimer presents two potential Get4 binding sites, a single Get4-5 hetero-tetramer would be unable to occupy both, as this would require steric clashes to Get3. The tetramer seen here then likely represents a pre-hydrolysis Get3 complex waiting for a TA substrate to trigger hydrolysis and release of the complex from Get4.

Figure 5. A working model for Get4-5.

(a) The tetramer of Get3 from the Get3D-Get4-5N crystal lattice in two orientations. Colored as in Fig. 2b. (b) The tetramer of an archaeal Get3 (PDB ID 3UG6 18) oriented similar to (a). (c) A model for the assembly of the Get3-Get4-Get5 tail-anchor binding complex. Colors correspond to those in Figure 2 and Figure 5.

Coupling this structural data and biochemistry with the current literature allows us to provide a refined model for TA selection by the Get3-Get4-5 complex (Fig. 5c). (1) In the absence of nucleotide Get3 is predominantly in the open conformation with low affinity for Get4-5. (2) Binding of ATP would shift Get3 to a closed conformation that would be recognized by Get4-5, and promote inhibition of Get3 ATPase activity. (3) A second Get3 dimer binding to the Get4-5 hetero-tetramer would follow. The complex would now be primed for capture of a TA substrate from the co-chaperone Sgt2 24 bound to the Ubl-domain of Get5 29. (4) The stabilized tetramer-TA complex results in ATP hydrolysis 31 causing release from Get4 and subsequent delivery to the ER.

In all organisms, cascades of protein biogenesis factors mediate the chaperoning and handover of nascent proteins from the ribosome to their final folding state or cellular destination. Active regulation of the conformation and nucleotide state of protein biogenesis factors, as studied here for Get3, has also been observed for the SRP-SRP receptor complex during co-translational protein targeting 32,33. This likely represents a general mechanism for ensuring efficient and productive biogenesis of nascent proteins.

METHODS

Protein cloning, expression, and purification

The sequences of Get4 and Get5 were cloned as previously described 27. To generate the Get4-5N used in this study, this construct was further modified by truncating the C-terminus of Get4 (residues 291–312), and by the addition of a stop codon after residue 54 within Get5. All S. cerevisiae Get4 mutants were generated using the QuikChange mutagenesis method (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. All Get4-5 proteins were overexpressed in BL21-Gold (DE3) (Novagen) grown in 2×YT media at 37 °C and induced for 3h by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were lysed using a microfluidizer (Microfluidics) and purified as a complex by Ni-affinity chromatography (Qiagen). The affinity tag was removed by an overnight TEV protease digest at room temperature while dialyzing against 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 30 mM NaCl and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME). A second Ni-NTA column was used to remove any remaining his-tagged protein then the sample was then loaded onto a 6 mL Resource Q anion exchange column (GE Healthcare). The peak containing the Get4-5N complex was collected and concentrated to 15–20 mg/mL. Initial purifications of the Get4-5N complex was verified to be a single monodispersed species over SEC using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM BME. Full-length Get4-5 used in ATPase assays and translocation experiments was further purified using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM K-HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM KOAc, 10 mM MgOAc, 10% (v/v) Glycerol, and 5 mM BME. Fractions containing Get4-5 were pooled and concentrated to ~5 mg/mL.

The S.cerevisiae Get3 coding region was cloned as previously described 13. A 6×His-tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site was fused to the N-terminus, and a stop codon was placed in front of the C-terminal 6×His-tag. All S. cerevisiae Get3 mutants were generated using the QuikChange method. Get3 mutants used in SEC, ITC, or capture assays were introduced into the Get3D construct, whereas mutants used in ATPase assays or translocation assays were introduced into the wildtype Get3 construct. All Get3 proteins were made in BL21-Gold(DE3), grown in 2×YT media and induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16h at 22°C. Cells were lysed using a microfluidizer (Microfluidics) and purified by Ni-affinity chromatography (Qiagen). The affinity tag was removed by an overnight TEV protease digest at room temperature while dialyzing against 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM BME. A second Ni-NTA column was used to remove any remaining his-tagged protein then the sample was run on a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with the dialysis buffer. Fractions corresponding to a dimer of Get3 were pooled and concentrated to 15–20 mg/mL. Get3 derivatives used for ATPase assays and translocation experiments were further purified over a MonoQ anion exchange column to remove contaminating ATPases.

Get3D-Get4-5N complex was formed by equilibrating 105 µmol Get4-5N with 100 µmol Get3D at room temperature in 500 µL of 20mM Tris pH 7.5, 10mM NaCl, 5mM BME, 1mM MgCl2, and 1mM of either AMP-PNP or ATP. Prior to complex formation, Get3 had been pre-equilibrated with 1mM MgCl2 and either 1mM AMP-PNP or ATP for 5min at room temperature. Get3-Get4-5N complex was further separated from free Get4-5N using a Superdex 200 10/300 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl and 5 mM BME or with 20 mM Bis-Tris Propane pH 9.0, 10 mM NaCl and 5 mM BME. All complexes were concentrated to 10–12 mg/mL before use in crystallization experiments.

Crystallization

Purified Get3D-Get4-5N complex was concentrated to 10–12 mg/ml and crystal trials were carried out using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at room temperature by equilibrating equal volumes of the protein complex solution and reservoir solution using a TTP LabTech Mosquito robot and commercially purchased kits (Hampton Research, Qiagen, Molecular Dimensions Limited). Get3D-Get4-5N crystals grew in the presence of 18% PEG 3350, 0.2 M KSCN, 0.1 M Bis-Tris Propane pH 9.0, and 5% DMSO. Crystals were cryoprotected by transferring directly to 10µL of a reservoir solution supplemented with 20% glycerol, 1mM ATP, and 1 mM MgCl2 and incubated for ≥10 minutes before being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection, structure solution, and refinement

All structures were solved using datasets collected on Beamline 12-2 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at 1 Å at ~100 K. Each structure was solved from a single dataset that was integrated using MOSFLM 35 or XDS 36, and scaled and merged using SCALA 37,38. Crystals of Get3D-Get4-5N diffracted to 5.4 Å and was solved by molecular replacement with PHASER 39 as implemented in PHENIX 40, using a monomer of the closed (ADP-AlF4) form of Get3 (PDB ID 2WOJ 14) and one Get4-5N heterodimer (PDB ID 3LKU 27) as search models. No solution was found using the open (apo) form of Get3 (3A37 17). Refinement was performed using REFMAC v6.3 with rigid body restraints and in CNS v1.2 41 using DEN refinement. Manual rebuilding was performed using COOT 42. The final model refined to an R-factor of 27.0% (Rfree = 32.8%) with residues in the Ramachandran plot in 92.2% preferred, 6.0% allowed, and 1.8% in the disallowed and restricted regions 42. Full statistics in Table 1.

Size exclusion chromatography for complex stability

250 µL of 25 µM Get3D and 250 µL of 25 µM Get4-5N were combined and dialyzed at room temperature in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME, 1 mM MgCl2, and, where indicated, 1 mM of either ADP or ATP. The total samples were injected onto a Superdex 200 10/300 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10–500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM BME.

Capture assay

500 nmol of 6×His-tagged Get4-5N was incubated with 10 µL Ni-NTA agarose resin for one hour at 4°C in 500µL binding buffer containing 20 mM K-HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM KOAc, 10 mM MgOAc, 10% (v/v) Glycerol, 25 mM imidazole, and 1 mM ADP or ATP where indicated. Following the addition of 1 µmol of Get3D, the solution was incubated for an hour at 4°C. After incubation, the reaction was spun for 30sec at 500×g. The supernatant was removed, and 500 µL binding buffer was added to the solution, and gently mixed through inversion. The wash step was repeated twice, and following the final wash, the remaining bound proteins were eluted with 30 µL of 20mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5mM BME, and 300 mM imidazole. The samples were spun for 30sec at 500 × g, and the supernatant was removed and added to 6 µL of 6×SDS-PAGE buffer. All samples were run on 15% SDS-PAGE gels and stained with Coomasie blue G-250. Gels were then analyzed by infared scanning in the 700 nm channel using a LI-COR Odyssey Infared Imaging System and Odyssey Application Software v3.0.30.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Get3D-Get4-5N binding experiments were carried out using the MicroCal iTC200 system (GE Healthcare). Binding affinities were measured by filling the sample cell with 50 µM Get3D and titrating 350 µM Get4-5N. The buffer conditions were identical for all samples and contained 20 mM K-HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM KOAc, 10 mM MgOAc, 10% (v/v) Glycerol, and 1mM ATP. For each experiment, 2 µl of Get4-5N was injected into Get3 for 20 intervals spaced 120 sec apart at 25°C. For the first titration, 0.4 µl of Get4-5N was injected. The stirring speed and reference power were 1000 rpm and 5 µcal/s. Affinity constants were calculated from the raw data using Origin v7.4 software (MicroCal).

ATPase assay

Get3 ATPase rates were measured as previously described 31. Briefly, the kcat for 8µM Get3 was determined in the presence of excess of ATP doped with (γ-32P) ATP, and analyzed by autoradiography. Each Get3 ATPase reaction was conducted in the presence or absence of excess (20µM) full-length Get4-5. For Fig. 4a, individual ratios were calculated for each of n independent trials (Supplementary Table 1) performed on separate days and then a mean and standard deviation were calculated across n ratios. Each independent trial was the average of values from two side-by-side reactions. Values used in Supplementary Table 1 are means and standard deviations calculated across n experiments.

Translocation assay

The coding sequence for yeast Sbh1 was cloned into a transcription plasmid 24 under control of an SP6 promoter and modified as previously described 31. Sbh1 mRNA was transcribed using the SP6 Megascript kit (Ambion). All translation and translocation assays were performed in yeast as previously described 18 using extracts and microsomes from either a Δget3 9 or Δget3/Δget5 24 strain. Get3 translocation efficiency was plotted as a function of Get3 concentration and analyzed as previously described 31.

Yeast growth assay

Knockout strains BY4741 YDL100C::KanMX (Get3) and BY4741 YOR164C::KanMX (Get4) were purchased from America Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and used as previously described 13,27. The Get3 rescue plasmid was constructed by PCR amplifying the open reading frame with 242 bp upstream and 263 bp downstream flanking regions from BY4741 genomic DNA. The Get4 rescue plasmid was constructed by PCR amplifying the open reading frame with 233 bp upstream and 86 bp downstream flanking regions from BY4741 genomic DNA. Both genes were amplified with SalI and NotI restriction sites and ligated into the pRS316 vector 43. Mutants were generated by Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis. Yeast strains were transformed using the Li/Ac/single-stranded carrier DNA/PEG method 44. Phenotypic rescue was determined by growing each transformant in SC-Ura media at 30 °C to an OD600 nm between 1 and 2, diluting to 3.85 × 106 cells/mL and spotting 4 µL of serial dilutions onto SC -Ura agar plates in the presence or absence of 2 mM CuSO4. Plates were then incubated at 30 °C or 40 °C for 24–48 h and photographed. The results were consistent through three trials.

Structure analysis and figures

Cartoon representations of protein structures were prepared using PyMol (Schrodinger, LLC), while surface representations were prepared using UCSF Chimera 45. Surface figures were made in Chimera. Conservation used values for individual residues based on an alignment from ClustalW 34. Electrostatic surface potentials were calculated using APBS with default values as implemented in the PDB2PQR webserver 46,47.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to V. Denic (Harvard University) for providing the Δget3/Δget5 yeast strain. We thank Graeme Card, Ana Gonzalez and Michael Soltis for help with data collection at SSRL BL12-2. We are grateful to Gordon and Betty Moore for support of the Molecular Observatory at Caltech. Operations at SSRL are supported by the US Department of Energy and US National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was supported by career awards from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Henry Dreyfus Foundation (S.-o.S.), US National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1144469 (M.E.R.), NIH training grant 5T32GM007616-33 (H.G. and M.R.) and NIH research grant R01GM097572 (W.M.C.).

Footnotes

Accession codes. Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the Get3D-Get4-5N complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 4PWX.

Author Contributions

H.B.G. performed all experiments except those noted. M.R. performed Get4 inhibition studies, and M.E.R. performed translocation experiments, both supervised by S-o.S. J.W.C. initiated the project and aided in refinement. S-o.S contributed to experimental design and interpretation. W.M.C. conceived and supervised the project. H.B.G. and W.M.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shao S, Hegde RS. Membrane protein insertion at the endoplasmic reticulum. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:25–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutay U, Hartmann E, Rapoport TA. A class of membrane proteins with a C-terminal anchor. Trends in cell biology. 1993;3:72–75. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90066-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutay U, Ahnert-Hilger G, Hartmann E, Wiedenmann B, Rapoport TA. Transport route for synaptobrevin via a novel pathway of insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. The EMBO journal. 1995;14:217–223. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgese N, Gazzoni I, Barberi M, Colombo S, Pedrazzini E. Targeting of a tail-anchored protein to endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial outer membrane by independent but competing pathways. Molecular biology of the cell. 2001;12:2482–2496. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgese N, Brambillasca S, Colombo S. How tails guide tail-anchored proteins to their destinations. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2007;19:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanovic S, Hegde RS. Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell. 2007;128:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favaloro V, Spasic M, Schwappach B, Dobberstein B. Distinct targeting pathways for the membrane insertion of tail-anchored (TA) proteins. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:1832–1840. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuldiner M, et al. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell. 2005;123:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuldiner M, et al. The GET complex mediates insertion of tail-anchored proteins into the ER membrane. Cell. 2008;134:634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonikas MC, et al. Comprehensive characterization of genes required for protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2009;323:1693–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1167983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battle A, Jonikas MC, Walter P, Weissman JS, Koller D. Automated identification of pathways from quantitative genetic interaction data. Molecular systems biology. 2010;6:379. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartron JW, Clemons WM, Jr, Suloway CJ. The complex process of GETting tail-anchored membrane proteins to the ER. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2012;22:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suloway CJ, Chartron JW, Zaslaver M, Clemons WM., Jr Model for eukaryotic tail-anchored protein binding based on the structure of Get3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14849–14854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907522106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mateja A, et al. The structural basis of tail-anchored membrane protein recognition by Get3. Nature. 2009;461:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature08319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bozkurt G, et al. Structural insights into tail-anchored protein binding and membrane insertion by Get3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:21131–21136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910223106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Li J, Qian X, Denic V, Sha B. The crystal structures of yeast Get3 suggest a mechanism for tail-anchored protein membrane insertion. PloS one. 2009;4:e8061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamagata A, et al. Structural insight into the membrane insertion of tail-anchored proteins by Get3. Genes to Cells. 2010;15:29–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suloway CJ, Rome ME, Clemons WM., Jr Tail-anchor targeting by a Get3 tetramer: the structure of an archaeal homologue. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:707–719. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukhopadhyay R, Ho YS, Swiatek PJ, Rosen BP, Bhattacharjee H. Targeted disruption of the mouse Asna1 gene results in embryonic lethality. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3889–3894. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariappan M, et al. The mechanism of membrane-associated steps in tail-anchored protein insertion. Nature. 2011;477:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature10362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefer S, et al. Structural basis for tail-anchored membrane protein biogenesis by the Get3-receptor complex. Science. 2011;333:758–762. doi: 10.1126/science.1207125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Whynot A, Tung M, Denic V. The mechanism of tail-anchored protein insertion into the ER membrane. Mol Cell. 2011;43:738–750. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto Y, Sakisaka T. Molecular machinery for insertion of tail-anchored membrane proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2012;48:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang F, Brown EC, Mak G, Zhuang J, Denic V. A chaperone cascade sorts proteins for posttranslational membrane insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum. Molecular Cell. 2010;40:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chartron JW, Gonzalez GM, Clemons WM., Jr A Structural Model of the Sgt2 Protein and Its Interactions with Chaperones and the Get4/Get5 Complex. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:34325–34334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costanzo M, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chartron JW, Suloway CJ, Zaslaver M, Clemons WM., Jr Structural characterization of the Get4/Get5 complex and its interaction with Get3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12127–12132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang YW, et al. Crystal structure of Get4-Get5 complex and its interactions with Sgt2, Get3, and Ydj1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:9962–9970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chartron JW, Vandervelde DG, Rao M, Clemons WM., Jr The Get5 carboxyl terminal domain is a novel dimerization motif that tethers an extended Get4/Get5 complex. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:8310–8317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.333252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang YW, et al. Interaction Surface and Topology of Get3-Get4-Get5 Protein Complex, Involved in Targeting Tail-anchored Proteins to Endoplasmic Reticulum. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:4783–4789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rome ME, Rao M, Clemons WM, Jr, Shan SO. Precise timing of ATPase activation drives targeting of tail-anchored proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:7666–7671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222054110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Rashid R, Wang K, Shan SO. Sequential checkpoints govern substrate selection during cotranslational protein targeting. Science. 2010;328:757–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1186743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ataide SF, et al. The crystal structure of the signal recognition particle in complex with its receptor. Science. 2011;331:881–886. doi: 10.1126/science.1196473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

METHODS REFERENCES

- 35.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CCP4, C.C.P.N.-. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunger A. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:31–34. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettersen E, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:W665–W667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.