Abstract

Tooth counts are commonly recorded in fossil diapsid reptiles and have been used for taxonomic and phylogenetic purposes under the assumption that differences in the number of teeth are largely explained by interspecific variation. Although phylogeny is almost certainly one of the greatest factors influencing tooth count, the relative role of intraspecific variation is difficult, and often impossible, to test in the fossil record given the sample sizes available to palaeontologists and, as such, is best investigated using extant models. Intraspecific variation (largely manifested as size-related or ontogenetic variation) in tooth counts has been examined in extant squamates (lizards and snakes) but is poorly understood in archosaurs (crocodylians and dinosaurs). Here, we document tooth count variation in two species of extant crocodylians (Alligator mississippiensis and Crocodylus porosus) as well as a large varanid lizard (Varanus komodoensis). We test the hypothesis that variation in tooth count is driven primarily by growth and thus predict significant correlations between tooth count and size, as well as differences in the frequency of deviation from the modal tooth count in the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary. In addition to tooth counts, we also document tooth allometry in each species and compare these results with tooth count change through growth. Results reveal no correlation of tooth count with size in any element of any species examined here, with the exception of the premaxilla of C. porosus, which shows the loss of one tooth position. Based on the taxa examined here, we reject the hypothesis, as it is evident that variation in tooth count is not always significantly correlated with growth. However, growth trajectories of smaller reptilian taxa show increases in tooth counts and, although current samples are small, suggest potential correlates between tooth count trajectories and adult size. Nevertheless, interspecific variation in growth patterns underscores the importance of considering and understanding growth when constructing taxonomic and phylogenetic characters, in particular for fossil taxa where ontogenetic patterns are difficult to reconstruct.

Keywords: Alligator, allometry, Crocodylus, dentition, Diapsida, Dinosauria, Reptilia, Varanus

Introduction

Due to their taphonomic resilience, large sample sizes, strong correlation with dietary behaviours and, for many groups, species-specific morphology, teeth have long been a critical tool for investigating the evolution, diversification, and ecology of fossil amniotes (e.g. Osborn, 1907; Gingerich, 1974; Massare, 1987; Farlow et al. 1991; Sues & Reisz, 1998; Reisz & Tsuji, 2006; Meloro & Jones, 2012; Larson & Currie, 2013; LeBlanc & Reisz, 2013; Brink & Reisz, 2014). These advantages, in particular the opportunity to make low-level taxonomic assignments, have provided palaeomammalogists with some of the best data regarding diversity, evolution, ontogeny, body size, and diet in mammals (e.g. Gingerich, 1974, 1976; Fox, 1990; Evans et al. 2006; Ungar, 2010; Wilson et al. 2012).

Tooth morphology, including shape, denticle counts, and microanatomy, are also commonly used for delimiting eureptilian (Diapsida + stem diapsids) taxa in the fossil record (Benton, 1984; Currie et al. 1990; Farlow et al. 1991; Larson, 2008; Hwang, 2010; Evans et al. 2013; Heckert & Miller-Camp, 2013; Young et al. 2013; Hendrickx & Mateus, 2014). Beyond aspects of shape, the number of tooth positions in each tooth-bearing element (tooth count) is often recorded and used in phylogenetic analyses in many groups, including captorhinids (Modesto et al. 2014), mosasaurid squamates (Konishi & Caldwell, 2011; Leblanc et al. 2012), plesiosaurs (Smith & Dyke, 2008), hadrosaurid dinosaurs (Prieto-Marquez, 2010), and theropod dinosaurs (Sereno, 1999; Holtz, 2000; Currie, 2003; Carrano et al. 2012; Hendrickx & Mateus, 2014). However, the phylogenetic and taxonomic utility of tooth counts in many groups at lower-level taxonomic resolution remains unclear and is hampered by a poor understanding of intraspecific variation. This intraspecific variation in tooth counts is difficult to test given the small sample sizes for many fossil taxa and can therefore only be evaluated adequately within the context of a non-mammalian extant model, such as diapsids.

The majority of research into tooth count variation in extant diapsids has focused on squamates (Kluge, 1962; Ray, 1965; Montanucci, 1968; Cooper et al. 1970; Arnold, 1980; Thorpe, 1983; Estes & Williams, 1984; Kline & Cullum, 1984; Dessem, 1985; Greer, 1991; Rasmussen, 1996). Within Squamata, most major lizard groups, including Iguanidae (Ray, 1965; Montanucci, 1968; Kline & Cullum, 1984), Gekkonidae (Kluge, 1962; Thorpe, 1983), Scincidae (Arnold, 1980; Greer, 1991), and Agamidae (Cooper et al. 1970), show distinct increases in the number of tooth positions associated with growth in both the maxilla and dentary within a species. This pattern of increasing tooth count through growth, although common, is by no means universal, as a relatively consistent number of tooth positions through growth were recorded in Teiidae (Dessem, 1985), Serpentes (Rasmussen, 1996), and some members of Scincidae (Delgado et al. 2003). Consistent tooth counts were also suggested for some varanid species (Mertens, 1942), but these patterns have yet to be investigated within the context of skull allometry. Finally, a decrease in the number of tooth positions through growth has been recorded in Anguidae (Cooper, 1966) and Lacertidae (Cooper, 1963; as cited in Cooper, 1966). Therefore, predicting tooth count trajectories is highly dependent on the extant model chosen.

In contrast to squamates, much less is known regarding tooth count variation in the other major radiation of extant diapsids, the archosaurs (including Pterosauria, Crocodylia and Dinosauria). Studies on the initial development of teeth in embryos and hatchlings of Alligator mississippiensis indicate that tooth count is variable and highly correlated with jaw growth (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986, 1987). Iordansky (1973) reported that the second premaxillary tooth is lost during the juvenile stages of post-hatching ontogeny in Crocodylus cataphractus, Crocodylus porosus, Crocodylus siamensis, and Tomistoma schlegelii. Yet, it is unclear when exactly in ontogeny this tooth loss occurs, and how strongly its loss is correlated with growth. Larson (2013) reported individual variation of up to two tooth positions in the maxilla and dentary, and one tooth position in the premaxilla in a sample of 20 species of extant crocodylians, and also noted that no ontogenetic trends were present in an analysis of 41 A. mississipiensis skulls.

Tooth replacement patterns in crocodylians have been studied extensively and suggest that teeth are replaced in a uniform regular pattern when animals are young, but the pattern becomes less uniform through life, and that the mesial-most teeth are replaced more quickly than the distal-most teeth (Edmund, 1960, 1962). Younger individuals shed their teeth quickly and replace them with larger teeth through growth, and the growth rate of tooth-bearing elements decreases with age (McIlhenny, 1935; Edmund, 1962). However, it is unknown how tooth counts vary with age and size in most species of crocodylians. The large change in body size that crocodylians undergo throughout ontogeny makes them good models for understanding the relationship between tooth count variation and growth in extinct dinosaurian archosaurs.

Here we investigate tooth count variation in crocodylians by documenting tooth counts in the maxilla, dentary, and premaxilla of A. mississippiensis and C. porosus across their recorded intraspecific size range. We also add to the growing body of literature on squamate tooth count variation by providing data for the largest extant squamate, Varanus komodoensis. We test the hypothesis that variation in tooth counts is driven by growth, as was observed in previous studies (e.g. Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986; Greer, 1991), and predict significant positive relationships between size (a proxy for relative age) and number of tooth positions. Secondly, we test for complementary changes in relative tooth size through growth. In amniotes with multiple tooth generations, we define two distinct models for how a growing tooth row can be filled with teeth: (i) increasing tooth size or (ii) increasing tooth number (tooth count). In the former, tooth size (anteroposterior length of teeth) will increase, either isometrically or positively allometrically with jaw length; tooth count can remain constant (or even decrease). In the second model, the number of tooth positions increases positively with jaw length, and tooth size can remain constant (i.e. no relationship to jaw length) or be negatively allometric. It is important to note that, biologically, these models are not entirely mutually exclusive; different combinations of absolute increase in tooth size and count are possible. However, given the limited space within a jaw, a concomitant increase in relative tooth size and tooth number seems doubtful. Therefore, these models should, in theory, oppose each other when filling the available space in a tooth row, resulting in an upper limit to their combined effect. A similar lower limit may not exist, as these would merely create diastema in the tooth row; teeth could decrease in size, either relatively or absolutely, and also decrease in number. These models are generally applicable to relatively homodont dentitions and do not make predictions regarding taxa with a heterodont dentition. Given our initial prediction of positive correlations between tooth counts and jaw size, we predict that tooth size should remain relatively constant throughout growth (i.e. tooth size increases isometrically relative to tooth row length). We also survey the literature and present current data on tooth count change within many species of extant squamates and extinct dinosaurs to illustrate the patterns exhibited by these clades. Testing the predictions outlined above will provide insights into the nature of variation of tooth counts in diapsids (intra- vs. interspecific variation) with implications for interpreting taxonomy and diversity in the fossil record.

Materials and methods

Sixty-one skulls of A. mississippiensis, 23 skulls of C. porosus, and 22 skulls of V. komodoensis were examined from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Australian Museum (AM), Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), Museum of the Rockies (MOR), Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (UMMZ), United States National Museum of Natural History (USNM), and Yale Peabody Museum (YPM). Tooth counts (Supporting Information Tables S1–S3) were taken for both the left and right side of the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary. Measurements of tooth row length were taken for each maxilla and dentary, as well as the anteroposterior diameter of the fourth (A. mississippiensis), fifth (C. porosus) or seventh (V. komodoensis) maxillary tooth and fourth (A. mississippiensis), fifth (C. porosus) or seventh (V. komodoensis) dentary tooth (Tables S1–S3). These tooth positions were chosen as they represent the largest tooth within the dental series, and as a result were easy to identify consistently if the number of teeth varied between individuals. Basal skull lengths, measured from the anterior-most tip of the premaxilla to the posterior-most tip of the occipital condyle, were also taken for each skull. These skulls range in size from 35 to 689 mm (A. mississippiensis), 107 to 578 mm (C. porosus), and 130 to 221 mm (V. komodoensis). All measurements were taken to the nearest millimeter. All length measurements were log-transformed (base 10) prior to analysis, and count data were left as integers. Left and right tooth rows were analyzed independently, and the results were not pooled for counts, regressions or correlations.

Within each taxon, the modal tooth count was determined for the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary. Variation in tooth counts was calculated by the number and frequency of deviations from the modal value for each element (independent) and for bilateral element pairs. Deviations from modal tooth count were categorized into either asymmetric deviations (a situation where the two sides showed differing tooth counts) or symmetric deviations (both left and right showing equal deviation from the mode). Tooth counts in each element were regressed against basal skull length using an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Correlations between basal skull length, a proxy for size and relative growth stage, and tooth count were tested using the Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient.

For both the maxilla and dentary, tooth counts and the anteroposterior length of the tooth (fourth for A. mississippiensis, fifth for C. porosus, and seventh for V. komodoensis) for both the left and right side (right only for V. komodoensis) were regressed (OLS) against tooth row length. To account for possible outliers in the regression analysis we also performed a robust regression on the same datasets, but our discussion will concentrate on the basic OLS regression. All references to ‘growth’ within the present study reflect increases in size along a continuous intraspecific size-series, and do not necessarily reflect relative age.

In addition to the new data presented here, we surveyed the existing literature and collected data on tooth count change through growth for a variety of living and extinct diapsid taxa, including dinosaurs (Supporting Information Table S4). For historical papers, where only the plots were illustrated and the raw data were not presented in table form, the data were extracted digitally using the program plotdigitizer (V. 2.6.3) (Huwaldt, 2014). Although this method will introduce some error in the measure of tooth row length, counts are less sensitive to such errors (due to rounding to the nearest whole number), and the overall pattern of tooth count change through increasing size should be preserved. In addition to published extant tooth count data, we also collected tooth count data for a selection of extinct non-avian dinosaur species, for which relatively complete size/growth series are known (Table S4). Data for non-avian dinosaurs were collected using the same methods as those for the extant samples, but due to small sample sizes, the pattern for left and right sides were averaged. Data were utilized to place our detailed case studies in a broader evolutionary context, and to present the overall patterns of tooth count change through growth in diapsids, as well as the possible effect of overall size on this pattern (all data obtained using plotdigitizer are provided in Table S4).

All analyses were conducted using standard packages in the r Statistical Language (V 3.0.2; R Core Development Team, 2013). The complete r code used for these analyses can be found in Supporting Information Data S1.

Results

Tooth count change through growth

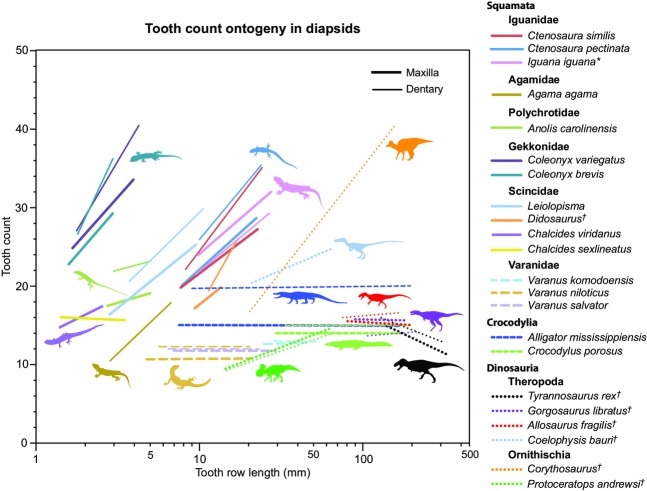

In A. mississippiensis, the modal premaxillary tooth count is five, maxillary tooth count is 15, and dentary tooth count is 20 across the entire size range (Fig.1, Tables1 and 2), with no change in tooth count correlated with size, all P-values > 0.05 (Supporting Information Table S5). Several skulls show deviations from this pattern, with asymmetrical (single side) and symmetrical (both side and same direction) deviations from this modal count exhibited (Tables1 and 2), but these deviations do not correlate with skull size. The proportion of specimens with tooth counts that differ from the modal count is different between the tooth-bearing elements (Table1). Deviations from the modal tooth count for each element are largely (68%) explained by asymmetry alone, rather than a deviation in tooth count from the norm on both left and right sides of the jaw (Fig.1A, Table1). Deviation from tooth count is also restricted in magnitude, with all but three deviant skulls (88%) showing deviations of only one tooth position. The proportion of specimens with tooth counts differing from the modal count is different between the tooth-bearing elements (Table1).

Figure 1.

Size-related tooth count change for the premaxilla (n = 116), maxilla (n = 120), and dentary (n = 112) of Alligator mississippiensis. (A) Plot of tooth counts as a function of basal skull length for the premaxilla (white), maxilla (grey), and dentary (black). Dots indicate both left and right, ‘L’ indicates only left, and ‘R’ indicates only right. Lines represent the slope of the OLS regression, and grey areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. (B) Histogram of tooth counts for both left and right sides.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the paired premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary of Alligator mississippiensis

| Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | Total skull | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 58 | 59 | 54 | 51 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 5 | 15 | 20 | 40 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.84 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.81 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.87 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 5 (9%) | 18 (31%) | 16 (30%) | 25 (49%) |

| 7 | Asymmetric frequency | 5 (9%) | 12 (20%) | 8 (15%) | 16 (27%) |

| 8 | Symmetric frequency | 0 (0%) | 6 (10%) | 8 (15%) | 9 (18%) |

| 9 | Proportion asymmetric (%) | 100 | 66.67 | 50 | 64 |

Table 2.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the individual premaxillae, maxillae, and dentaries of Alligator mississippiensis

| Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 116 | 120 | 112 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 5 | 15 | 20 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.45 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.58 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 5 (9%) | 24 (20%) | 26 |

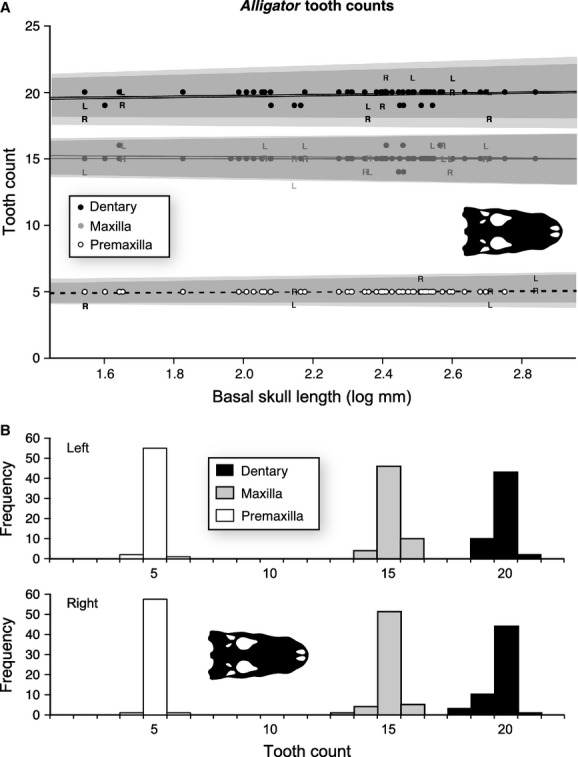

The data for C. porosus show a similar pattern to that of A. mississippiensis, with the modal tooth count of 14 and 15 for the maxilla and dentary, respectively (Fig.2, Tables3 and 4), and with neither element showing an increase or decrease though growth (Table S5). The premaxilla, however, shows a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in tooth count from five to four through the size series (Fig.2B, Table S5). As with A. mississippiensis, the rate of deviation from modal tooth count is relatively low (43%) and largely explained by asymmetry (50–100%, depending on the element) (Fig.2A, Table3). Again, similar to A. mississippiensis, the magnitude of tooth count deviations is quite low, with all deviations being only one tooth position.

Figure 2.

Size-related tooth count change for the premaxilla (n = 46), maxilla (n = 46), and dentary (n = 46) of Crocodylus porosus. (A) Plot of tooth counts as a function of basal skull length for the premaxilla (white), maxilla (grey), and dentary (black). Dots indicate both left and right, ‘L’ indicates only left, and ‘R’ indicates only right. Lines represent the slope of the OLS regression. (B) Histogram of tooth counts for both left and right sides.

Table 3.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the paired premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary of Crocodylus porosus

| Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 5 | 14 | 15 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.47 | 0 | 0.21 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.49 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.47 | 0 | 0.30 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 9 (39%) | 0 | 2 (9%) |

| 7 | Asymmetric frequency | 3 (13%) | 0 | 2 (9%) |

| 8 | Symmetric frequency | 6 (26%) | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Proportion asymmetric (%) | 33.33 | NaN | 100 |

Table 4.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the individual premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary of Crocodylus porosus

| Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 46 | 46 | 46 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 5 | 14 | 15 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.47 | 0 | 0.21 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.49 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.47 | 0 | 0.30 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 15 (32%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

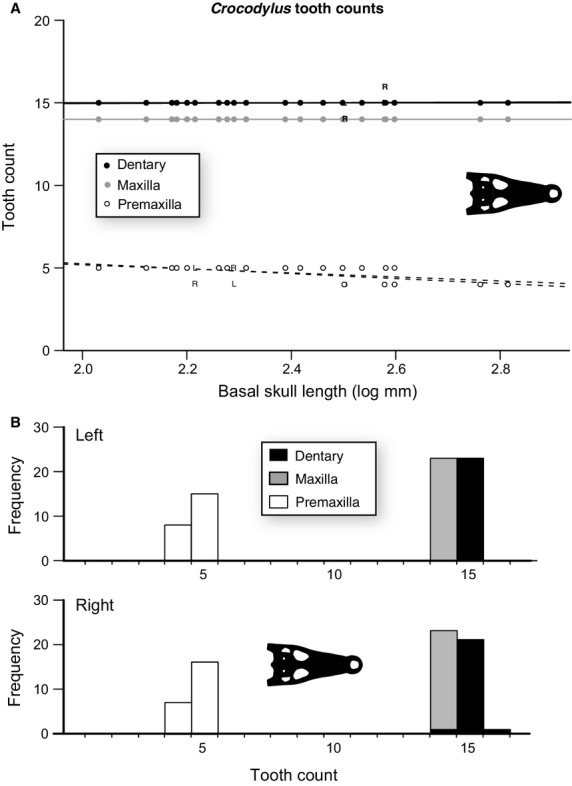

Finally, tooth count data for V. komodoensis also show similar patterns to that of the two crocodylians, with tooth number in all three major tooth-bearing elements (premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary) showing no correlation with skull length (Fig.3, Tables5, 6 and S5). The modal tooth count is four for the premaxilla, 13 for the maxilla, and 13 for the dentary (Tables5 and 6). All deviations from the modal tooth count in the premaxilla and maxilla, and 60% of those in the dentary are due to asymmetry in tooth counts between left and right sides (Fig.3A, Table5).

Figure 3.

Size-related tooth count change for the premaxilla (n = 36), maxilla (n = 42), and dentary (n = 40) of Varanus komodoensis. (A) Plot of tooth counts as a function of basal skull length for the premaxilla (white), maxilla (grey), and dentary (black). Dots indicate both left and right, ‘L’ indicates only left, and ‘R’ indicates only right. Lines represent the slope of the OLS regression. (B) Histogram of tooth counts for both left and right sides.

Table 5.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the paired premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary of Varanus komodoensis

| Varanus by skull/paired elements | Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 18 | 21 | 20 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 4 | 13 | 13 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.31 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.49 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 1 (6%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (25%) |

| 7 | Asymmetric frequency | 1 (6%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (15%) |

| 8 | Symmetric frequency | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10) |

| 9 | Proportion asymmetric (%) | 100 | 100 | 60 |

Table 6.

Summary statistics for tooth counts for the individual premaxillae, maxillae, and dentaries of Varanus komodoensis

| Varanus – by element | Premaxilla | Maxilla | Dentary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size (n) | 36 | 42 | 40 |

| 2 | Mode tooth count | 4 | 13 | 13 |

| 3 | Tooth count SD - Total | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| 4 | Tooth count SD - Left | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.31 |

| 5 | Tooth count SD - Right | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.49 |

| 6 | Total deviations from mode | 1 (3%) | 3 (7%) | 7 (18%) |

Tooth size allometry

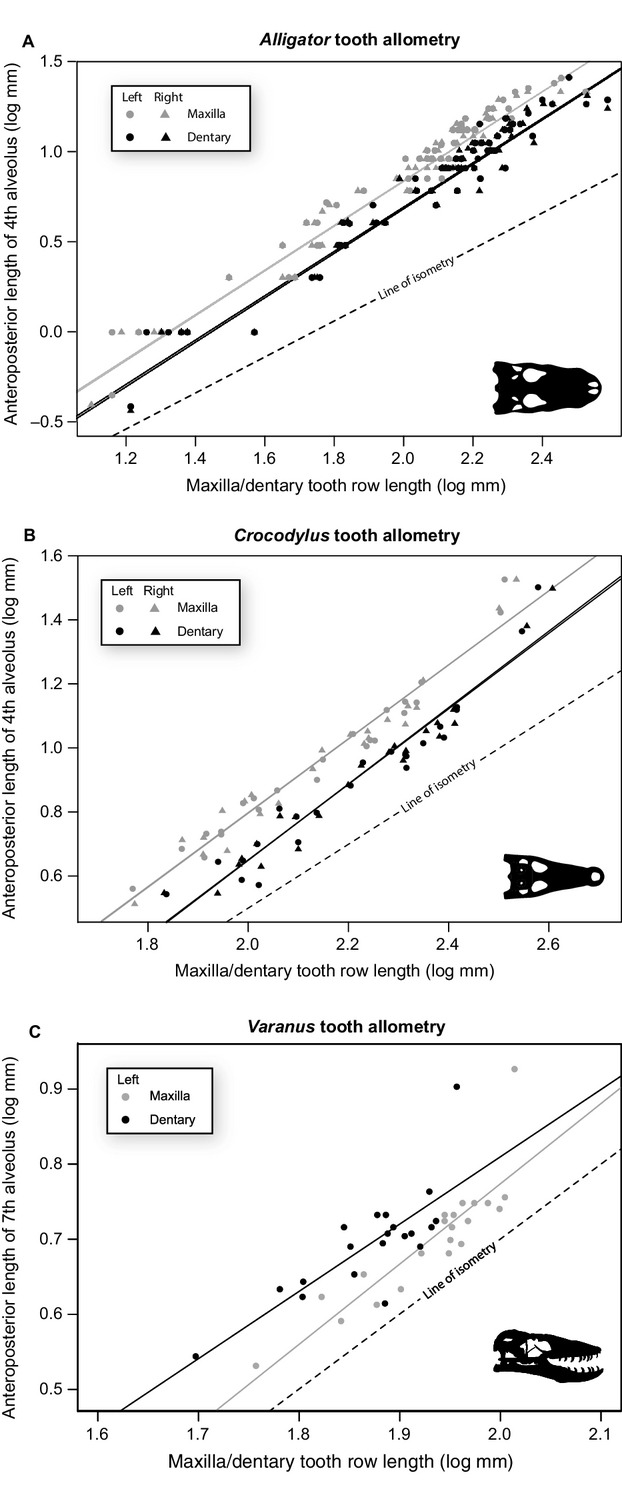

Maxillary and dentary tooth size in A. mississippiensis, based on the fourth alveolus and relative to tooth row length, exhibits positively allometric trends (Fig.4A, Table7). The mean and 95% confidence intervals for the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression are all greater than a slope of one. Positive allometry in tooth size is also noted in C. porosus (Fig.4B, Table7). These patterns are consistent on both the right and left maxillae and dentaries independently for A. mississippiensis and C. porosus (Fig.4). The dataset for V. komodoensis is smaller than those for A. mississippiensis and C. porosus, and although the slope of the relationship for the maxilla is greater than one and the dentary is less than one, the 95% confidence intervals of both include one, and therefore cannot be statistically differentiated from isometry (Fig.4C, Table7). The results for the robust regression (Supporting Information Table S6) are largely consistent with that of the OLS regression. Differences between the two analyses are present only in the datasets with smaller sample sizes and likely represent differences in statistical power between the tests.

Figure 4.

Tooth allometry for the fourth (Alligator mississippiensis), fifth (Crocodylus porosus), and seventh (Varanus komodoensis) tooth against tooth row length of both A. mississippiensis (A) C. porosus (B), and V. komodoensis (C), respectively. Left (circles) and rights (triangles) are plotted separately for both the maxilla (grey) and dentary (black). Dashed line indicates a slope of 1.

Table 7.

Results of allometry analysis of anteroposterior length of fourth (Alligator), fifth (Crocodylus), and seventh (Varanus) maxillary and dentary tooth regressed against tooth row length

| Maxilla | Dentary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | |

| A. mississippiensis | ||||

| Slope | 1.25 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.24 |

| Upper CI | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.31 | 1.32 |

| Lower CI | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.16 |

| Allo. Trend | + | + | + | + |

| C. porosus | ||||

| Slope | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.18 | 1.19 |

| Upper CI | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.31 |

| Lower CI | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 |

| Allo. Trend | + | + | + | + |

| V. komodoensis | ||||

| Slope | 1.07 | − | 0.89 | − |

| Upper CI | 1.35 | − | 1.24 | − |

| Lower CI | 0.79 | − | 0.55 | − |

| Allo. Trend | Iso. | − | Iso. | − |

Allo. Trend, allometric trend.

Discussion

Tooth count change through growth

Although a modest body of literature exists on changes in tooth counts through growth in some squamates, crocodylians are more poorly documented, and the relationship between tooth allometry and tooth counts is not well understood. The results of this study suggest that, for A. mississippiensis and C. porosus, as well as for V. komodoensis, the tooth counts in the maxilla and dentary do not change through the size series, and most cases of deviation in tooth count are explained by left–right asymmetry in the jaw. The results for A. mississippiensis are consistent with that of a previous study that employed a smaller sample size (Larson, 2013). These findings indicate that deviations from the modal number likely relate to individual variation, independent of size. This same pattern is characteristic of the premaxilla of A. mississippiensis and V. komodoensis. The premaxilla of C. porosus, however, does show a distinct trend towards a loss of a tooth position (decreased tooth count from five to four teeth) that is correlated with size (Iordansky, 1973). The loss of a tooth position is not due to ‘packing’ of teeth in the premaxilla, but rather the growth of the first dentary tooth. As the first dentary tooth grows, it forms a prominent foramen in the tooth row of the premaxilla, which subsequently leads to the exclusion of a premaxillary tooth position (Fig.5). One specimen (FMNH 10866) has this foramen only on the left premaxilla. In FMNH 10866, the second premaxillary tooth was lost on the left side, but was not reduced in size on the right (Fig.5). Therefore, it appears that the loss of this tooth is dependent on the development of the dentary tooth associated with this foramen, rather than on an independent resorption at a specific time in the animal's life. Taken together, these results falsify our initial prediction that growth and tooth counts are significantly correlated in the taxa examined here with the exception of the decrease in premaxillary tooth counts in C. porosus.

Figure 5.

Ventral (palatal) view of the premaxilla of Crocodylus porosus specimen FMNH 10899. The left side shows a large foramen for receipt of the first dentary tooth (indicated by arrow), and as a result the second premaxillary tooth is lost. On the right side, this foramen is not developed and the second premaxillary tooth is retained. Scale bar: 5 cm.

Alligator mississippiensis and C. porosus both show significant positive allometry of anteroposterior tooth length, in the measured position, relative to the length of the tooth row, indicating that the anteroposterior space occupied by the tooth increases faster than the tooth row length. This increase in relative tooth size while maintaining constant tooth count is somewhat counter-intuitive, as one would expect these two metrics to act reciprocally. This pattern may be explained by a combination of two factors. First, the measurement of the tooth row and teeth did not take into account the spacing between adjacent alveoli. If sufficient space exists between alveoli in small individuals (particularly juveniles), a decrease in spacing through growth may accommodate the allometric increase in alveolar size while maintaining a constant number of alveoli. The alternative possibility is that the allometry of the measured tooth does not adequately represent the growth patterns exhibited by other teeth within the tooth row, and although teeth examined here grow via positive allometry, other teeth may exhibit a more isometric or even negatively allometric pattern. Although our qualitative observations suggest the former, the present dataset does not allow for a quantitative test of these two factors (or any combination therein). Nevertheless, the results indicate that allometry and tooth count changes throughout growth are not strictly dependent on each other. A similar pattern was noted in Iguana iguana (Kline & Cullum, 1984), which supports this conclusion.

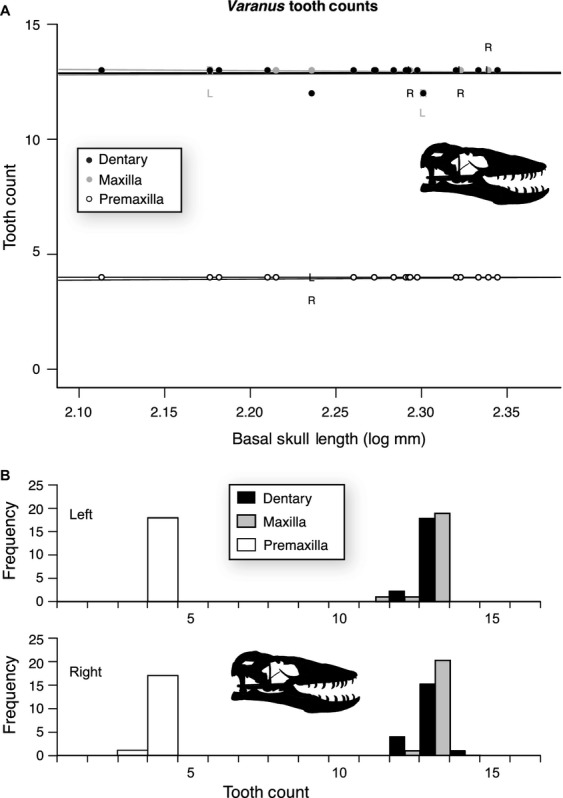

Body size and tooth count variation in Diapsida

The results of combining the existing literature-derived data on squamate and dinosaur tooth count changes (Kluge, 1962; Ray, 1965; Montanucci, 1968; Cooper et al. 1970; Dodson, 1976; Madsen, 1976; Arnold, 1980; Colbert, 1990; Delgado et al. 2003; Torres-Carvajal, 2007) with our new data for V. komodoensis, A. mississippiensis, C. porosus, and extinct non-avian dinosaurs are reported in Fig.6. The majority of non-varanid squamates show distinct increases in tooth counts through their growth. In contrast, data for V. komodoensis and the crocodylians presented here show unchanging tooth count across their respective size series. The data for ornithischians show a pattern of increasing tooth counts as body size increases, best illustrated by the hadrosaurid taxon Corythosaurus, and to a lesser degree in the ceratopsian Protoceratops. The preliminary data for non-avian theropods show a range of possible changes, with Coelophysis bauri showing an increase, Allosaurus fragilis and Gorgosaurus libratus showing a relatively stable count, and Tyrannosaurus rex (with the potentially conspecific Nanotyrannus lancensis included) showing a decrease in tooth count across the size series.

Figure 6.

Overview figure illustrating patterns of tooth count change across size in many species of extant and extinct diapsids. Each line indicates the best fit line for a species. Colours and pattern (solid, dotted, dashed) indicate different taxa, and thickness indicates element (thick = maxilla, thin = dentary). Taxon silhouettes for Figure 6 obtained from the PhyloPic website (phylopic.org) under attribution (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) or public domain. Artist credit: Craig Dylke, Andrew Farke, Ghedo, Rebecca Groom, Scott Hartman, Michael Keesey, Michael Scroggie, Smokeybjb, Steve Traver, Sarah Werning, Emily Willoughby.

Tooth count growth patterns across the diapsid size range reveal a potential trend in which the slope (tooth counts in relation to log tooth row length) is correlated, at least loosely, with overall body size. Smaller taxa have positive trajectories (increase in tooth counts throughout growth), crocodylians, Varanus, and the large-bodied theropods Allosaurus and Gorgosaurus show little or no changes in tooth counts through their respective size series, and T. rex shows a potential negative trend. When these slopes are regressed against published snout–vent lengths (SVL) for extant taxa only, the slopes of size-related tooth count changes for the dentary and maxilla are both significantly and negatively correlated with SVL (dentary: m = −0.266, r2 = 0.34, P < 0.05; maxilla: m = −0.236, r2 = 0.56, P < 0.01, respectively). Interestingly, despite our small sample size, the interspecific negative trajectories observed here for the dentary and maxilla conform to the theoretical expectation that size-specific rates (i.e. size-related variation in morphological or physiological properties) scale to the power −0.25 (Peters, 1983). When A. mississippiensis and C. porosus are taken out of the dataset, the significant correlation between tooth count slope and SVL is lost for the dentary (m = −0.257, r2 = 0.20, P > 0.05) but not the maxilla (m = −0.222, r2 = 0.40, P < 0.05). Extrapolation of such interspecific trajectories would predict that as diapsids attain larger sizes (e.g. T. rex) tooth counts may be expected to decrease throughout growth, but this contradicts the pattern observed through growth in large ornithischian dinosaurs (Fig.6). More data are needed to determine whether the observed patterns are truly related to body size, rather than disparate phylogenetic histories.

Conclusions

Understanding tooth count variation and the mechanisms that govern that variation is an important step towards understanding the evolution of jaw and tooth development in diapsids. This study demonstrates that no universal pattern exists for tooth count change through growth in diapsids (Fig.6). Consequently, without additional data for a particular taxonomic group, tooth counts alone are not reliable indicators of species demarcation in the fossil record. Indeed, even taxa with the same allometric tooth count pattern may achieve that pattern through multiple underlying mechanisms. These mechanisms include changes in tooth row length, anteroposterior tooth diameter, and possibly the space between alveoli. The results of this study indicate that these variables and the allometric relationships between them should be measured and considered in future studies examining tooth growth in diapsids to determine which of these variables are determining tooth counts in particular taxa. Finally, clade-specific allometric effects of tooth counts and tooth size must be incorporated if tooth count characters are used to diagnose fossil taxa or construct phylogenetic characters, as these characters are too variable to be determined by the extant phylogenetic bracket.

Acknowledgments

Access to specimens was provided by K. Seymour, R. MacCulloch, A. Lathrop, and N. Richards (ROM), D. Kizirian and R. Pascocello (AMNH), R. Sadlier and C. Beatson (AM), A. Resetar and K. Kelly (FMNH), J. Rosado (MCZ), G. Schneider (UMMZ), A. Wynn (USNM), and G. Watkins-Colwell (YPM). P. Currie, H. VanBuren, M. MacDougall, and A. LeBlanc provided useful discussion. J. Clarke (editor), E. Maxwell (reviewer), and an anonymous reviewer provided useful feedback on a previous version of this manuscript. Funding was provided in part by the Dinosaur Research Institute and an NSERC Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship to D.W.L., an Ontario Graduate Scholarship to C.M.B., K.S.B., and C.S.V., and an NSERC Discovery Grant to D.C.E.

Author contributions

C.M.B. designed the project. C.M.B., C.S.V., D.W.L., K.S.B., N.E.C., M.J.V., and D.C.E. contributed data. C.M.B., C.S.V., D.W.L., N.E.C., and M.J.V. analyzed the data. C.M.B. and C.S.V. made figures. C.M.B., C.S.V., D.W.L., K.S.B., N.E.C., M.J.V., and D.C.E. wrote the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Table S1. Tooth counts and measurements of Alligator mississippiensis.

Table S2. Tooth counts and measurements of Crocodylus porosus.

Table S3. Tooth counts and measurements of Varanus komodoensis.

Table S4. Tooth counts and tooth row lengths for a number of extant and extinct diapsids.

Table S5. Results of correlation (Kendall) of tooth count and basal skull length for the premaxilla, maxilla and dentary of Alligator mississippiensis, Crocodylus porosus and Varanus komodoensis.

Table S6. Results of the robust regression for tooth allometry plotting tooth length as a function of tooth row length in Alligator mississippiensis, Crocodylus porosus, and Varanus komodoensis.

Data S1.r code used in analyses.

References

- Arnold EN. Recently extinct reptile populations from Mauritius and Reunion, Indian Ocean. J Zool. 1980;191:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Benton MJ. Tooth form, growth, and function in Triassic rhynchosaurs (Reptilia, Diapsida) Palaeontology. 1984;27:737–776. [Google Scholar]

- Brink KS, Reisz RR. Hidden dental diversity in the oldest terrestrial apex predator Dimetrodon. 2014. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3269, doi: 10.1038/ncomms4269. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carrano MT, Benson RB, Sampson SD. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) J Syst Paleontol. 2012;10:211–300. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert EH. Variation in Coelophysis bauri. In: Carpenter K, Currie P, editors. Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 81–90. ) [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JS. Bristol University: 1963. Dental anatomy of the genus Lacerta. Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JS. Tooth replacement in the Slow worm (Anguis fragilis. J Zool. 1966;150:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JS, Poole DFG, Lawson R. The dentition of agamid lizards with special reference to tooth replacement. J Zool. 1970;162:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Currie PJ. Cranial anatomy of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Acta Palaeontol Pol. 2003;48:191–226. [Google Scholar]

- Currie PJ, Rigby JKJ, Sloan RE. Theropod teeth from the Judith River Formation of southern Alberta, Canada. In: Carpenter K, Currie PJ, editors. Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S, Davit-Beal T, Sire JY. Dentition and tooth replacement pattern in Chalcides (Squamata; Scincidae) J Morphol. 2003;256:146–159. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessem D. Ontogenetic changes in the dentition and diet of Tupinambis (Lacertilia: Teiidae) Copeia. 1985;1985:245–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson P. Quantitative aspects of relative growth and sexual dimorphism in Protoceratops. J Paleontol. 1976;50:929–940. [Google Scholar]

- Edmund AG. Tooth Replacement Phenomena in the Lower Vertebrates. Contrib Life Sci Div, R Ont Mus. 1960;52:1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Edmund AG. Sequence and Rate of Tooth Replacement in the Crocodilia. Contrib Life Sci Div, R Ont Mus. 1962;56:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Estes R, Williams EE. Ontogenetic variation in the molariform teeth of lizards. J Vertebr Paleontol. 1984;4:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Evans AR, Wilson GP, Fortelius M. High-level similarity of dentitions in carnivorans and rodents. Nature. 2006;445:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature05433. , et al. ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DC, Larson DW, Currie PJ. A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) with Asian affinities from the latest Cretaceous of North America. Naturwissenschaften. 2013;100:1041–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00114-013-1107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow JO, Brinkman DL, Abler WL. Size, shape and serration density of theropod dinosaur lateral teeth. Modern Geol. 1991;16:161–198. , et al. ( [Google Scholar]

- Fox RC. Geol Soc Am Spec Publ. 1990;243:51–70. The succession of Paleocene mammals in western Canada. Dawn of the age of mammals in the northern part of the Rocky Mountain interior, North America. [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich PD. Size variability of the teeth in living mammals and the diagnosis of closely related sympatric fossil species. J Paleontol. 1974:48, 895–903. [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich PD. Paleontology and phylogeny: patterns of evolution at the species level. Am J Sci. 1976;276:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Greer AE. Tooth number in the scincid lizard genus Ctenotus. J Herpetol. 1991:473–477. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Heckert AB, Miller-Camp JA. Tooth enamel microstructure of Revueltosaurus and Krzyzanowkisaurus (Reptilia:Archosauria) from the Upper Triassic Chinle Group, USA: implications for function, growth, and phylogeny. Palaeontol Electron. 2013;16:23. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx C, Mateus O. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the identification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa. 2014;3759:1–74. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3759.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz TR. A new phylogeny of the carnivorous dinosaurs. Gaia. 2000;15:61. [Google Scholar]

- Huwaldt JA. 2014. Plot Digitizer.

- Hwang SH. The utility of tooth enamel microstructure in identifying isolated dinosaur teeth. Lethaia. 2010;43:307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Iordansky NN. The skull of the Crocodilia. In: Gans C, editor. Biology of the Reptilia, Volume 4; Morphology D. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 201–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kline LW, Cullum D. A long term study of the tooth replacement phenomenon in the young green iguana, Iguana iguana. J Herpetol. 1984:18; 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge AG. Comparative osteology of the eublepharid lizard genus Coleonyx Gray. J Morphol. 1962;110:299–332. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Caldwell MW. Two new plioplatecarpine (Squamata, Mosasauridae) genera from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, and a global phylogenetic analysis of plioplatecarpines. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2011;31:754–783. [Google Scholar]

- Larson DW. Diversity and variation of theropod dinosaur teeth from the uppermost Santonian Milk River Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Alberta: a quantitative method supporting identification of the oldest dinosaur tooth assemblage in Canada. Can J Earth Sci. 2008;45:1455–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Larson P. The Case for Nanotyrannus. In: Parrish JM, Molnar RE, Currie PJ, Koppelhus EB, editors. Tyrannosaurid Paleobiology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2013. pp. 15–53. ) [Google Scholar]

- Larson DW, Currie PJ. Multivariate analyses of small theropod dinosaur teeth and implications for paleoecological turnover through time. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc ARH, Reisz RR. Periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone in the oldest herbivorous tetrapods, and their evolutionary significance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc ARH, Caldwell MW, Bardet N. A new mosasaurine from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) phosphates of Morocco and its implications for mosasaurine systematics. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2012;32:82–104. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen JH. Allosaurus fragilis: a revised osteology. Utah Geol Survey Bull. 1976;109:1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Massare JA. Tooth morphology and prey preference of Mesozoic marine reptiles. J Vertebr Paleontol. 1987;7:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- McIlhenny EA. The Alligator's Life History. Boston: Christopher Publishing House; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Meloro C, Jones M. Tooth and cranial disparity in the fossil relatives of Sphenodon (Rhynchocephalia) dispute the persistent ‘living fossil’ label. J Evol Biol. 2012;25:2194–2209. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens R. Die Familie der Warane (Varanidae) Zweiter Teil: der Schadel. Abh Senckenberg Nat Ges. 1942;462:1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Modesto SP, Lamb AJ, Reisz R. The captorhinid reptile Captorhinikos valensis from the lower Permian Vale Formation of Texas, and the evolution of herbivory in eureptiles. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2014;34:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Montanucci RR. Comparative dentition in four iguanid lizards. Herpetologica. 1968;24:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn HF. Evolution of Mammalian Molar Teeth: To and from the Triangular Type Including Collected and Revised Researches Trituberculy and New Sections on the Forms and Homologies of the Molar Teeth in the Different Orders of Mammals. New York: Macmillan; 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Peters RH. The Ecological Implications of Body Size. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Marquez A. Global phylogeny of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) using parsimony and Bayesian methods. Zool J Linn Soc London. 2010;159:435–502. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team. 2013. Vienna, Austria R Foundation for Statistical Computing R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 3.0.2.

- Rasmussen JBd. Maxillary tooth number in the African tree-snakes genus Dipsadoboa. Journal of Herpetology. 1996;30:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ray CE. Variation in the number of marginal tooth positions in three species of iguanid lizards. Breviora. 1965;236:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Reisz RR, Tsuji LA. An articulated skeleton of Varanops with bite marks: the oldest known evidence of scavenging among terrestrial vertebrates. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2006;26:1021–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Sereno P. The evolution of dinosaurs. Science. 1999;284:2137–2147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AS, Dyke GJ. The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:975–980. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sues H-D, Reisz RR. Origins and early evolution of herbivory in tetrapods. TREE. 1998;13:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe RS. A biometric study of the effects of growth on the analysis of geographic variation: tooth number in Green geckos (Reptilia: Phelsuma. J Zool. 1983;201:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Carvajal O. Heterogeneous growth of marginal teeth in the Black Iguana Ctenosaura similis (Squamata: Iguania) J Herpetol. 2007;41:528–531. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar PS. Mammal Teeth: Origin, Evolution, and Diversity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B, Ferguson M. Development of the dentition in Alligator mississippiensis. Early embryonic development in the lower jaw. J Zool. 1986;210:575–597. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B, Ferguson M. Development of the dentition in Alligator mississippiensis. Later development in the lower jaws of embryos, hatchlings and young juveniles. J Zool. 1987;212:191–222. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001870407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GP, Evans AR, Corfe IJ. Adaptive radiation of multituberculate mammals before the extinction of dinosaurs. Nature. 2012;483:457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature10880. , et al. ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MT, Andrade MB, Brusatte SL. The oldest known metriorhynchid super-predator: a new genus and species from the Middle Jurassic of England, with implications for serration and mandibular evolution in predacious clades. J Syst Paleontol. 2013:11,475–513. , et al. ( [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Tooth counts and measurements of Alligator mississippiensis.

Table S2. Tooth counts and measurements of Crocodylus porosus.

Table S3. Tooth counts and measurements of Varanus komodoensis.

Table S4. Tooth counts and tooth row lengths for a number of extant and extinct diapsids.

Table S5. Results of correlation (Kendall) of tooth count and basal skull length for the premaxilla, maxilla and dentary of Alligator mississippiensis, Crocodylus porosus and Varanus komodoensis.

Table S6. Results of the robust regression for tooth allometry plotting tooth length as a function of tooth row length in Alligator mississippiensis, Crocodylus porosus, and Varanus komodoensis.

Data S1.r code used in analyses.