Abstract

Objective

Lack of engagement in self-care is common among patients needing to follow a complex treatment regimen, especially patients with heart failure who are affected by comorbidity, disability and side effects of poly-pharmacy. The purpose of Motivational Interviewing Tailored Interventions for Heart Failure (MITI-HF) is to test the feasibility and comparative efficacy of an MI intervention on self-care, acute heart failure physical symptoms and quality of life.

Methods

We are conducting a brief, nurse-led motivational interviewing randomized controlled trial to address behavioral and motivational issues related to heart failure self-care. Participants in the intervention group receive home and phone-based motivational interviewing sessions over 90-days and those in the control group receive care as usual. Participants in both groups receive patient education materials. The primary study outcome is change in self-care maintenance from baseline to 90-days.

Conclusion

This article presents the study design, methods, plans for statistical analysis and descriptive characteristics of the study sample for MITI-HF. Study findings will contribute to the literature on the efficacy of motivational interviewing to promote heart failure self-care.

Practical Implications

We anticipate that using an MI approach can help patients with heart failure focus on their internal motivation to change in a non-confrontational, patient-centered and collaborative way. It also affirms their ability to practice competent self-care relevant to their personal health goals.

Keywords: Heart failure, Self-care, Self efficacy, Study design, Motivational interviewing, Physical function

1. Introduction

Heart failure is a cardiovascular syndrome affecting more than 5.7 million Americans [1]. It is growing in prevalence with 870,000 new cases diagnosed each year, especially among patients older than 80 years [1]. The management of heart failure is complex because it often occurs in the context of multiple chronic conditions [2]. Each chronic condition requires specific self-care, making prioritization a persistent challenge. The promotion of self-care helps to decrease symptom prevalence and prevent re-hospitalization of patients with heart failure [3]. Initiating effective self-care for early signs and symptoms of heart failure may delay the onset of acute decompensation and a heart failure hospitalization [4, 5]. In part due to the high cost of hospitalizations, about $39 billion was spent on heart failure treatment in the U.S. in 2012 [6]; hence, better strategies for patient engagement in self-care are high priority.

Self-care for patients with heart failure has been defined as a naturalistic decision-making process comprised of both self-care maintenance and self-care management [7, 8], as detailed in The Situation Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-care [7]. Self-care maintenance involves choosing positive health practices that may help to prevent an acute exacerbation (e.g. taking medication as prescribed, consuming a low-salt diet, staying physically active, and monitoring daily weight). Self-care management builds on these routine behaviors and includes critical decision-making and follow-up actions around managing signs and symptoms when they occur (e.g., taking an extra diuretic for shortness of breath) [7–9]. Heart failure self-care must be adapted to the individual because each person has his or her own symptom experience, functional disability, values, and motivations for engaging in self-care.

Traditionally, patient education programs focus on disseminating didactic information. However, patient-education alone is rarely sufficient to influence self-care behaviors, especially in the case of heart failure where there are often competing co-morbidities including diabetes mellitus (38%), hypertension (73%), kidney disease (46%) and obesity (47%), [2] in addition to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and cognitive impairment [10–12]. Overall, educational approaches for improving heart failure self-care have been developed and tested with little impact on heart failure outcomes [13, 14].

Early evidence from two pilot studies [15, 16] suggested that a motivational interviewing (MI) intervention was beneficial for adults with heart failure by improving their self-care. Riegel and colleagues reported that the MI approach was effective in increasing patient engagement in discussions of self-care [15] and Paradis and colleagues reported improved confidence in performing self-care behaviors [16]. Ogedegbe and colleagues tested whether MI would improve adherence to anti-hypertensive medication among hypertensive African American patients [17] and found that MI was effective [18]. Building upon both a pilot study and existing literature, Motivational Interviewing Tailored Interventions for Heart Failure (MITI-HF) was designed to improve heart failure self-care maintenance behaviors using MI.

MI is grounded in client-centered counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and social cognitive therapy [19]. MI also incorporates the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change, which assesses a patient’s readiness to change behavior and develops strategies to move toward taking action to change behavior [20]. MI integrates the concepts of relationship building from humanistic therapy [21] with active strategies oriented towards stages of change [20]. The main characteristics of MI are: expressing empathy, developing discrepancy between believe and behavior, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy [22]. The interviewer maintains a nonjudgmental approach and allows the patient to determine the need for behavioral change, rather than offering unsolicited advice on the need for change. The interviewer only explores ways to implement change once the patient expresses the desire and confidence to change. The goal of MI is to help individuals work through inherent ambivalence present in problematic or unhealthy behaviors, [22, 23] and to help them verbally express their own reasons for or against change using a nonjudgmental, empathetic, and encouraging tone [24]. MI can help people identify how their current behaviors conflict with their ability to achieve personal health goals, especially in the context of low readiness to change [24].

MI was initially developed for the treatment of substance abuse [25–27]. Due to its strong theoretical base and empirical support, MI is now used for patients with a wide variety of behaviors including illicit drug abuse, eating disorders, HIV risk behavior, and gambling [28]. It is also used for helping patients manage asthma and cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure in acute and outpatient settings [15, 29–31]. Brodie and colleagues used MI to increase physical activity among older adults with heart failure [29], as well as general and disease specific quality of life [30]. MI has specifically been used to improve heart failure self-care in small pilot studies [15, 16]; however, larger studies like the Ogedegbe study [18] are needed to build the body of evidence and confirm the preliminary albeit promising results of smaller pilot trials.

To address the reality of relatively brief interchanges between providers and patients in clinical settings, Rollnick and Heather developed “brief MI” which can be implemented in short (10-minute) medical consultations. While originally designed for treating addictions, the brief MI approach has wide application to other chronic diseases, including the treatment of both obesity and diabetes in pediatric and adult populations [32]. Brief interventions have been used effectively to reduce consumption of alcohol [33].

This article describes the study design and research methods used to evaluate MITI-HF (Clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT02177656), a randomized controlled trial to determine the feasibility and efficacy of MI to improve self-care and patient-oriented outcomes (acute physical symptoms and quality of life).

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

MITI-HF is a prospective, pilot randomized single-site trial. Participants are randomized to either the MI intervention or usual care. The MI group receive patient educational materials in the hospital; one home visit post-hospitalization and 3–4 follow-up phone calls by a nurse over 90 days. The usual care group receives patient educational materials while they are in the hospital and care as usual post-hospitalization. The primary outcome is change in self-care over 90-days. Secondary outcomes include changes in physical HF symptoms and quality of life. This study is carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki [34].

2.2 Eligibility

All eligible patients were screened for health literacy [35] and cognitive impairment (using a six-item screener derived from the Mini Mental Status Exam) [36]. Adults with heart failure are enrolled into the MITI-HF study from two urban inpatient cardiology units. To be included, participants have to: 1) be hospitalized with a primary or secondary diagnosis of heart failure, 2) be able to read and speak English, 3) be 18 years of age or older 4) live in a setting where they can independently engage in self-care, 5) live within 30 miles of the university hospital 6) have at least adequate health literacy, 7) have symptomatic heart failure (New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–IV) and 8) be willing to participate. Exclusion criteria include: 1) being on a Milrinone drip, 2) being on a list for an implanted ventricular assist device or heart transplant, 3) pregnancy, 4) psychosis and 5) cognitive impairment significant enough to impair the ability to give true informed consent, participate in the intervention, or complete the study instruments.

2.3 Data and safety monitoring

The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment and all data collection procedures are in accordance with the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

2.4 Baseline and follow-up assessment

Clinical information (e.g. etiology and type of heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and comorbid illnesses) are abstracted from patients’ electronic medical records by trained research assistants. NYHA functional class is administered to each participant by a research assistant and scored class I–IV by a single board certified cardiologist using data obtained from a standardized interview [37]. Comorbid conditions are scored using the Charlson comorbidity index. Detailed information on participants’ medications, with doses, are collected at baseline. Sociodemographic characteristics are self-reported.

In the first month of data collection, we realized that the 6-item screening tool for cognition was not adequate to pick up some cases of severe cognitive impairment [36]. In response, a second screening was put in place two weeks after discharge and before the baseline questionnaires were completed. If participants had no recollection of the study or of signing the informed consent during the baseline call, they were excluded from the study on the grounds that cognition was not adequate to proceed. Research assistants collect the data on the baseline questionnaires over the phone approximately two weeks after hospital discharge. Follow-up data are collected 90-days after baseline data collection.

2.5 Randomization and blinding

To achieve balance in the study groups on important demographic and clinical characteristics and increase statistical power, randomization is performed by minimization using the Minim program. [38] Participants are stratified based on NYHA functional class and gender. Randomization to the intervention or usual care group occurs after the informed consent form is signed and a cardiologist scores NYHA functional class. One of the principal investigators and all research assistants are blinded to which group participants are randomized. The other principal investigator was not blinded so as to remain fully available to staff for questions around study implementation.

2.6 Motivational interviewing intervention

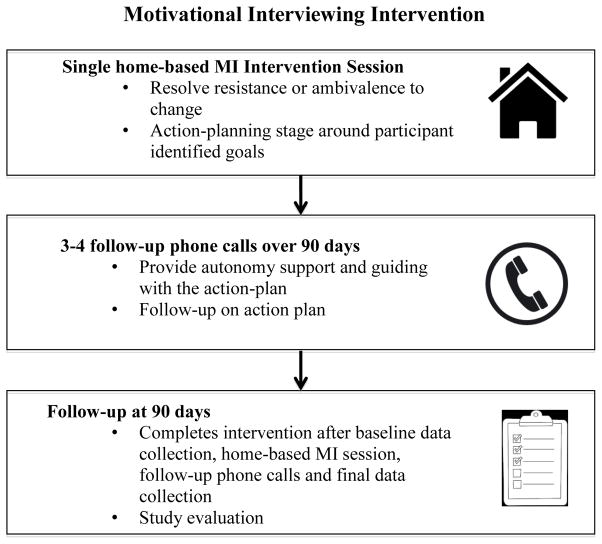

Heart failure specialist nurses serve as the interventionists providing the MI intervention. Each participant is randomized to a nurse and that nurse follows the participant throughout the study. The intervention includes one home-based MI intervention session followed by three to four phone calls over 90 days (Figure 1). Based on our prior work with MI, we anticipate that one 60-minute session and three to four follow-up phone calls scheduled over the following few months will be adequate to deliver this intervention [15]. The intervention begins with the nurse working with the participant on resolving resistance or ambivalence to change on specific aspects of self-care. The conversation then transitions toward action planning. Prior to meeting the participant, the nurse also has access to the Self-Care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI) results, which indicate low-scoring items that can be used as points of dialogue around goal development between the nurse and participant. For example, if a participant scores 1 “Never or rarely” or 2 “Sometimes” on the question, “How routinely do you do some physical activity?” and articulates that his goal is: “to be able to attend my grandson’s football games this fall,” then the nurse tailors the intervention on physical activity as a way of achieving his goals. Importantly, the client-centered style is consistent throughout the process of building motivation where advice and preventative support are provided without slipping into an overtly educational or directive style [39]. Action reflections are distinct from other types of reflections such as focusing on client feelings, rolling with resistance or acknowledging ambivalence by containing participant’s directly or indirectly articulated goals [39]. Over the course of the 90-day follow-up period, the nurse provides advice and preventative support over the phone.

Figure 1.

Stages of the MI intervention

KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

SCHFI: Self Care of Heart Failure Index

HFSPS: Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale

2.7 Interventionist Training

Before starting the study, two bachelor’s degree prepared nurse interventionists received two full days of training covering detailed aspects of MI theory and heart failure-specific self-care techniques and skills. The principal investigators and an expert in MI supervised both training days. Given the importance of communication skills training and better outcomes in studies where skills practice has taken place [40], the interventionists developed their MI skills through patient simulation and role-play scenarios with one another and the facilitators prior to interacting with study participants. Lane and colleagues demonstrated that trainees in MI can reach the same level of competence after a training session by practicing with a simulated patient or a fellow trainee [41].

2.8 Treatment fidelity and integrity

Treatment fidelity, defined as a methodological strategy used to monitor and enhance the reliability and validity of the intervention [42], is monitored throughout the intervention. All intervention sessions are digitally recorded, transcribed and analyzed to assess treatment fidelity. Prior to implementation of the protocol, a standardized rubric was developed based on the intervention manual to score adherence to the study protocol. The standardized rubric provides an ongoing mechanism for providing corrective feedback to the interventionists regarding deviations from the study protocol. One principal investigator reviews each audio recording using the rubric to determine the proportion of the intervention elements covered by the nurse interventionist. In addition to ongoing feedback with the interventionists, a psychologist and certified trainer in MI also reviews random transcripts and provides feedback to the interventionists on the quality of MI as well as adherence to the protocol.

2.9 Usual care control group

All study participants receive patient education materials designed by Krames StayWell for a 6th grade or below literacy level, according to the Fog Index (Table 1) [43]. The photographic images in the materials are commensurate with the demographics and culture of the study population. For instance, the “Busting Barriers” sheet pictures three generations of African American males to reinforce the benefits of social and familial support. All of the educational sheets target goal behavior changes through participant interaction, such as writing down the names of support people who would help them see habits that might block their progress toward change. Individuals randomized to the usual care group receive care as usual without any additional intervention.

Table 1.

Patient Education Materials

| Patient Education Sheet | Educational content areas |

|---|---|

| Busting Self-Care Barriers | Helps patients to identify possible challenges to self- care in order to prevent them from becoming barriers; recommendations include being active, reducing salt, limiting fluid, taking an extra water pill, and calling a healthcare provider. |

| Breaking Down Your Barriers | Describes how to take steps to improve self-care, identify support people, and benefits of self-care behaviors. |

| Dealing with Heart Failure Symptoms | Helps patients record baseline information such as weight, walking distance, and amount of stairs able to climb before becoming short of breath. |

| Watch for Changes | Describes how to monitor symptom changes and it offers tips for limiting salt and fluids. |

| Stay Active to Help Your Heart | Focuses on how to incorporate activity into a daily routine, including how to choose an activity and warning signs of overexertion. |

| Adding Activity to Your Day | Includes tips for making activity part of your day, and for how to keep it fun by walking with friends or reading a book while on an exercise bike. |

| My Heart Failure Symptom Chart | Provides a chart for recording daily weight, change from baseline weight and symptoms. |

| My Symptom Action Plan | Recording action plans for different scenarios of worsening heart failure symptoms, including swelling, increased shortness of breath, and weight gain of two or more pounds in one day. |

2.10 Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome: Self Care of Heart Failure Index

Self-care is measured using the SCHFI v. 6.2, a 22-item, interviewer-administered instrument that quantifies HF patients’ self- care maintenance, self-care management, and self-care confidence (self-efficacy) [8, 44]. Each scale score ranges from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate better self-care. Factor score determinacy reliability coefficients range between 0.78 and 0.90 for the self-care maintenance and management scores [45]. Self-care confidence is uni-dimensional and the various reliability coefficients, including Cronbach’s alpha, ranged from 0.84 to 0.90 [45]. In a recent exploratory factor analysis, the construct validity scores were 0.92 for self-care maintenance, 0.95 for self-care management and 0.99 for self-care confidence [46]. Convergent validity of the SCHFI self-care maintenance score has been demonstrated by comparing it to the European Health Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (r= −0.59, p<0.001) [47].

Secondary Outcome: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)

Quality of life is measured with the KCCQ, which has 23 items that can be quantified into five subscales: physical limitations, symptoms, quality of life, social interference, and self-efficacy. The overall and domain-specific subscales range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better outcomes [48]. In another population of patients with heart failure the internal consistency of the KCCQ is reported to be high (Cronbach’s α 0.92) [49]. Tests of construct validity for the KCCQ have strong associations with NYHA class, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 Health Survey and the six minute-walk-test [48].

Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS) v. 3

Acute physical symptoms are measured with the HFSPS. Scores are calculated by summing responses; higher values reflect worse physical symptom distress. The responses to the 18-items range from 0 (I did not have this symptom) to 5 (extremely bothersome) [50]. The total score ranges from 0 to 90 with higher scores indicating worse physical symptom distress [51]. The reported reliability of the HFSPS scale is 0.90 [52]. Validity was demonstrated when the two domains, dyspnea (6-items, range 0–30 points) and early/non-specific congestion (7-items, range 0–35 points) were associated with survival at 180 and 365-days [51].

Hospitalizations

Hospitalizations during the study are measured with both self-report and confirmed with the electronic health record.

2.11 Sample size and power

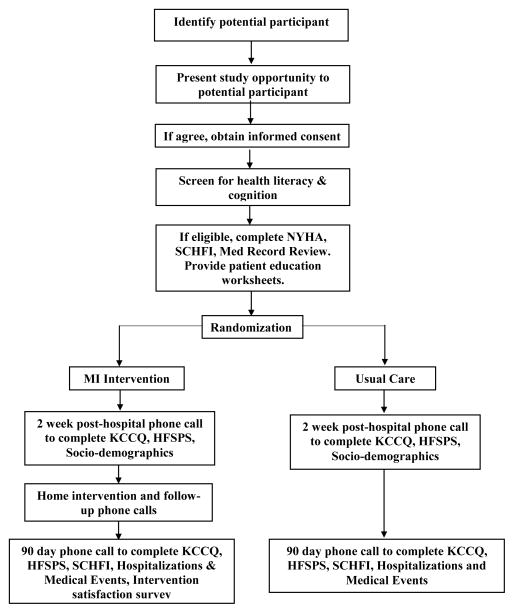

The target sample size is 65 participants; however, to account for an estimated 35% attrition rate, 100 participants will be recruited (Figure 2). The estimated attrition rate was based on pilot data in this sample population. The target sample size was calculated based on a 2:1 randomization scheme (intervention: control) with 90% power (5% alpha) to detect a difference of 80% versus 50% (intervention and control group) of scoring over 70 on the Self Care of Heart Failure Index, which is the cut-off for adequate self-care [44] at three months. The power analysis was performed using G*Power [53] and confirmed with PASS [54].

Figure 2.

MITI-HF Study Flow Diagram

2.12 Planned Statistical analyses

Standard descriptive statistics of frequency, central tendency, and dispersion will be used to describe all measures of the study at baseline. Comparisons of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the intervention and usual care groups at baseline will be reported using Student’s t, Pearson χ2 analysis or ANOVA where appropriate. Differences between groups in improvements in self-care will be quantified using t-tests without assuming equal variance; Cohen’s d is calculated as a standardized index of effect size. Repeated measures tests are used within subjects. Analyses will be conducted using StataSE (College Station, Texas) using intention-to-treat. Effect sizes will be calculated with G*Power [53].

3.0 Preliminary Results

Overall, one hundred participants have been randomized to an intervention or a usual care group. The mean age of participants is 61 years; they are predominantly male (67%) and self-identify as African American (57%). A majority of participants (64%) have no more than a high school education and 31% report not having enough financial support to live on. The majority of participants (59%) have HF with left ventricular ejection fraction < 35% and are functionally compromised (85% NYHA Class III/IV). Participants have an average of 5.4 comorbidities; 70% report having hypertension, 50% diabetes, 32% atrial fibrillation, 21% pulmonary hypertension and 13% chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. On average, participants take 11.5 medications a day. The majority of participants self-report their health as poor or fair (67%). In terms of social support, 78% of people report living with another person, 94% have someone to confide in, 56% are single and 85% report having good or very good quality support.

4.0 Discussion

This article describes the development and implementation of MITI-HF, a randomized controlled trial testing a tailored MI intervention to support heart failure self-care. The anticipated strength of the study is high participation of African Americans with multiple chronic conditions. The anticipated weaknesses are the lack of an objective self-care measure (e.g. pedometer for exercise) and study attrition. The significance of this study is that it tests an innovative MI intervention that has high potential to be integrated into transitional care discharge planning services. Future articles will present the results of the study and implications for heart failure research and clinical practice.

We anticipate that using an MI approach can help patients with heart failure focus on their internal motivation to change in a non-confrontational, patient-centered, and collaborative way. It also affirms their ability to practice competent self-care relevant to their personal health goals.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Edna G Kynett Memorial Foundation. We would also like to thank Krames StayWell, specifically P.J. Bell, Wendy Hiller Gee and Stephanie Manning for designing the patient education materials for all study participants. We gratefully acknowledge the pre-doctoral funding for Ruth Masterson Creber provided by the National Hartford Centers of Geriatric Nursing Excellence Patricia G. Archbold Scholarship program (2012–2014) and NIH/NINR (F31NR014086-01). We also acknowledge the post-doctoral funding for Ruth Masterson Creber by NIH/NINR (T32 NR007969, PI: Dr. Suzanne Bakken) at Columbia University School of Nursing. The authors would also like to acknowledge Thomas A. Gillespie, MD, FACC for scoring the NYHA interviews. We would also like to acknowledge psychologist Brenda Reis, PhD and Janet McMahon, MSN, RN for participating in the MI training and in the treatment fidelity of the intervention and Linda Hoke, PhD, RN for her assistance with recruiting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ruth Masterson Creber, Columbia University, School of Nursing.

Megan Patey, University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing.

Victoria Vaughan Dickson, New York University, College of Nursing.

Marissa DeCesaris, University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing.

Barbara Riegel, University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2015 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014 Dec 17; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong CY, Chaudhry SI, Desai MM, Krumholz HM. Trends in comorbidity, disability, and polypharmacy in heart failure. Am J Med. 2011 Feb;124:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CS, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Riegel B. Event-free survival in adults with heart failure who engage in self-care management. Heart Lung. 2011 Jan-Feb;40:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuyuki RT, McKelvie RS, Arnold JM, Avezum A, Jr, Barretto AC, Carvalho AC, et al. Acute precipitants of congestive heart failure exacerbations. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Oct 22;161:2337–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connell JB. The economic burden of heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2000 Mar;23:Iii6–10. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960231503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Mar 1;123:933–44. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riegel B, Dickson VV. A situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008 May-Jun;23:190–6. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305091.35259.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riegel B, Carlson B, Moser DK, Sebern M, Hicks FD, Roland V. Psychometric testing of the self-care of heart failure index. J Card Fail. 2004 Aug;10:350–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riegel B, Lee CS, Dickson VV. Self care in patients with chronic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011 Jul 19;19:644–54. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pressler SJ. Cognitive functioning and chronic heart failure: a review of the literature (2002–July 2007) J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008 May-Jun;23:239–49. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305096.09710.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dardiotis E, Giamouzis G, Mastrogiannis D, Vogiatzi C, Skoularigis J, Triposkiadis F, et al. Cognitive impairment in heart failure. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:595821. doi: 10.1155/2012/595821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogels RL, Oosterman JM, van Harten B, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM, Schroeder-Tanka JM, et al. Profile of cognitive impairment in chronic heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Nov;55:1764–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeWalt DA, Schillinger D, Ruo B, Bibbins-Domingo K, Baker DW, Holmes GM, et al. Multisite randomized trial of a single-session versus multisession literacy-sensitive self-care intervention for patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2012 Jun 12;125:2854–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dracup K, Moser DK, Pelter MM, Nesbitt T, Southard J, Paul SM, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Self-Care in Patients with Heart Failure Living in Rural Areas. Circulation. 2014 May 9; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riegel B, Dickson VV, Hoke L, McMahon JP, Reis BF, Sayers S. A motivational counseling approach to improving heart failure self-care: mechanisms of effectiveness. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 May-Jun;21:232–41. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paradis V, Cossette S, Frasure-Smith N, Heppell S, Guertin MC. The efficacy of a motivational nursing intervention based on the stages of change on self-care in heart failure patients. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010 Mar-Apr;25:130–41. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181c52497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A, Richardson T, Lewis L, Belue R, Espinosa E, et al. An RCT of the effect of motivational interviewing on medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007 Feb;28:169–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Feb 27;172:322–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.RS, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992 Sep;47:1102–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.RS, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Borrelli B, Hecht J, Ernst D. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychology. 2002;21:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001 Dec;96:1725–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noonan WC, Moyers TB. Motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Use. 1997 Jan 01;2:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson DR, Chair SY, Chan SW, Astin F, Davidson PM, Ski CF. Motivational interviewing: a useful approach to improving cardiovascular health? J Clin Nurs. 2011 May;20:1236–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodie DA, Inoue A. Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2005 Jun;50:518–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodie DA, Inoue A, Shaw DG. Motivational interviewing to change quality of life for people with chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008 Apr;45:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill CA. Acute heart failure: too sick for discharge teaching? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2009 Apr-Jun;32:106–11. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181a27ccd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christie D, Channon S. The potential for motivational interviewing to improve outcomes in the management of diabetes and obesity in paediatric and adult populations: a clinical review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014 May;16:381–7. doi: 10.1111/dom.12195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCambridge J, Rollnick S. Should brief interventions in primary care address alcohol problems more strongly? Addiction. 2014 Jul;109:1054–8. doi: 10.1111/add.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rickham PP. Human Experimentation. Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br Med J. 1964 Jul 18;2:177. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5402.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Aug;21:874–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002 Sep;40:771–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubo SH, Schulman S, Starling RC, Jessup M, Wentworth D, Burkhoff D. Development and validation of a patient questionnaire to determine New York Heart Association classification. J Card Fail. 2004 Jun;10:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans S, Day S, Royston P. Minim: allocation by minimisation in clinical trials. 2013 Available: http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~mb55/guide/minim.htm.

- 39.Resnicow K, McMaster F, Rollnick S. Action reflections: a client-centered technique to bridge the WHY-HOW transition in Motivational Interviewing. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2012 Jul;40:474–80. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane C, Rollnick S. The use of simulated patients and role-play in communication skills training: a review of the literature to August 2005. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Jul;67:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane C, Hood K, Rollnick S. Teaching motivational interviewing: using role play is as effective as using simulated patients. Med Educ. 2008 Jun;42:637–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, et al. Enhancing Treatment Fidelity in Health Behavior Change Studies: Best Practices and Recommendations From the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Govoni N. Dictionary of marketing communications. Vol. 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2004. Fog Index; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riegel B, Lee CS, Dickson VV, Carlson B. An update on the self-care of heart failure index. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009 Nov-Dec;24:485–97. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181b4baa0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbaranelli C, Lee CS, Vellone E, Riegel B. Dimensionality and reliability the self-fare of heart failure index scales: further evidence from confirmatory factor analysis. doi: 10.1002/nur.21623. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vellone E, Riegel B, Cocchieri A, Barbaranelli C, D’Agostino F, Antonetti G, et al. Psychometric testing of the self-care of heart failure index version 6.2. Res Nurs Health. 2013 Jul 7; doi: 10.1002/nur.21554. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Lee CS, Lyons KS, Gelow JM, Mudd JO, Hiatt SO, Nguyen T, et al. Validity and reliability of the European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale among adults from the United States with symptomatic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013 Apr;12:214–8. doi: 10.1177/1474515112469316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Apr;35:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masterson Creber RM, Polomono R, Ferrar J, Riegel B. Psychometric Properties of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2012 Jun;11:197–206. doi: 10.1177/1474515111435605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jurgens CY, Fain JA, Riegel B. Psychometric testing of the heart failure somatic awareness scale. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 Mar-Apr;21:95–102. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jurgens CY, Lee CS, Riegel B. Patient Perception of Heart Failure Symptoms Predicts One-Year Survival. presented at the American Heart Association; Dallas, TX. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jurgens CY, Lee CS, Reitano JM, Riegel B. Heart failure symptom monitoring and response training. Heart Lung. 2013 Jul-Aug;42:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]