Abstract

The majority of existing research on the function of metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptor 1 focuses on G protein-mediated outcomes. However, similar to other G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), it is becoming apparent that mGlu1 receptor signaling is multi-dimensional and does not always involve G protein activation. Previously, in transfected CHO cells, we showed that mGlu1 receptors activate a G protein-independent, β-arrestin-dependent signal transduction mechanism and that some mGlu1 receptor ligands were incapable of stimulating this response. Here we set out to investigate the physiological relevance of these findings in a native system using primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. We tested the ability of a panel of compounds to stimulate two mGlu1 receptor-mediated outcomes: (1) protection from decreased cell viability after withdrawal of trophic support and (2) G protein-mediated phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis. We report that the commonly used mGlu1 receptor ligands quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD are completely biased towards PI hydrolysis and do not induce mGlu1 receptor-stimulated neuroprotection. On the other hand, endogenous compounds including glutamate, aspartate, cysteic acid, cysteine sulfinic acid, and homocysteic acid stimulate both responses. These results show that some commonly used mGlu1 receptor ligands are biased agonists, stimulating only a fraction of mGlu1 receptor-mediated responses in neurons. This emphasizes the importance of utilizing multiple agonists and assays when studying GPCR function.

Keywords: metabotropic glutamate receptor 1, biased agonism, glutamate, quisqualate, DHPG, cerebellar granule cells

1. Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) make up the largest class of membrane receptors and are the target of the majority of current pharmaceuticals (Reiter et al., 2012). Classically, stimulation of these receptors causes activation of their associated G proteins and production of second messengers. Various GPCRs also partake in G protein independent signal transduction, the most studied of which is β-arrestin-dependent signaling. These G protein-independent cascades activate downstream enzymes in temporally and spatially different patterns compared to G protein-dependent activation (DeWire et al., 2007). Thus, it is not surprising that G protein-independent signals result in cellular and physiological outcomes that are distinct from those mediated by G protein stimulation (Luttrell and Gesty-Palmer, 2010).

As we understand more about the complexities of GPCR signaling it is apparent that receptor activation is not as simple as on and off (Rajagopal et al., 2010). Indeed, many GPCR ligands exhibit biased agonism: unequal ability (i.e. efficacies) to stimulate different responses mediated by a single receptor (Rajagopal et al., 2011). Because of the multidimensionality of GPCR signaling and agonism, it is important to assay numerous agonists and responses when characterizing GPCR signaling. Such rigorous investigations not only provide a more complete picture of receptor function, but also provide the framework for development of selective therapeutics that potentially reduce side effects by specifically activating one receptor outcome (Luttrell and Gesty-Palmer, 2010; Violin et al., 2014).

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors are GPCRs primarily expressed in the nervous system. mGlu receptors are divided into three groups based on sequence homology and G protein-coupling (Conn and Pin, 1997; Nakanishi, 1992). Group I mGlu receptors, which include mGlu1 receptors and mGlu5 receptors, are coupled to Gαq proteins. Thus, activation of group I mGlu receptors stimulates phospholipase C, resulting in hydrolysis of PIP2 and formation of the second messengers IP3 and DAG (Ferraguti et al., 2008). Additionally, glutamatergic activation of mGlu1 receptors stimulates a G protein-independent, β-arrestin-dependent signal transduction mechanism that protects mGlu1 receptor-transfected CHO cells from toxicity after serum withdrawal (Emery et al., 2010). Similar increases in cell viability upon glutamate treatment occur in multiple cell types and are dependent on mGlu1 receptor activation (Gelb et al., 2014; Pshenichkin et al., 2008). Activation of the protective, β-arrestin-dependent pathway does not occur with exogenous, group I mGlu receptor-preferring agonists (e.g. quisqualate), but only with endogenous agonists such as glutamate and aspartate (Emery et al., 2012). These findings suggest that activation of mGlu1 receptors may protect neurons from apoptosis. As targeting of mGlu1 receptors could be a potential neuroprotective strategy (Caraci et al., 2012), it is vital to fully characterize mGlu1 receptor signaling in native systems.

The purpose of this study was to investigate mGlu1 receptor signaling in a physiologically relevant model. Primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells were utilized as mGlu1 receptors are highly expressed in these neurons (Santi et al., 1994). To maximize culture viability, granule cells must be maintained in chronic depolarizing conditions (>20 mM potassium) since granule cells undergo apoptosis in concentrations of potassium that are physiological (5 mM). Granule cell death in this model occurs quickly and is reproducible, which is why the potassium removal paradigm is commonly used to study neurotoxicity and neuroprotection (see Contestabile 2002 for thorough review). Using primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells we characterized mGlu1 receptors using a panel of eight mGlu1 receptor ligands (glutamate, aspartate, cysteic acid, homocysteic acid, cysteine sulfinic acid, quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD). The response to each ligand was determined by two mGlu1 receptor-dependent outcomes: protection from toxicity after potassium removal and phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis. We report here that native mGlu1 receptors exhibit biased agonism in primary neuronal cultures. These findings confirm the neuroprotective potential of mGlu1 receptors and emphasize the need for further drug design endeavors to selectively activate this protective mechanism while potentially reducing side effects.

2. Methods

2.1 – Materials

Neurobasal (NB) media, 2 M KCl, B27 supplement, L-glutamine, and gentamicin were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Receptor agonists (glutamate, aspartate, quisqualate, 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), (1S,3R)-1- aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (ACPD), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)), receptor antagonists (YM298198-HCl, CPCCOEt, JNJ16259685, MPEP, MK801, CFM2, MCCG, MAP4) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom). All receptor agonists were prepared in equimolar sodium hydroxide (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) and adjusted to pH 7.3 – 7.5. All antagonists were diluted in DMSO (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), except for MPEP, which was prepared in water. Glutamate pyruvate transaminase (GPT) was obtained from Roche (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2 – Cell cultures

Primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons were prepared as described previously (Wroblewski et al., 1985) using cerebella dissected from P7 Sprague-Dawley rat pups. Cerebellar granule cells were plated in 100 μl at a density of 8×105 cells/cm2 on Nunclon Delta Surface 96-well plates (VWR) coated with poly-L-lysine. Cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) was added the day after plating to prevent growth of non-neural cells. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in culture media (Neurobasal media containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin, 2 mM glutamine, 2% B27 supplement, and 25 mM KCl) for 5 to 6 days in vitro (DIV). For experimentation, granule cells were maintained overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 in Neurobasal containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin and either 25 mM KCl (K25 conditions) or 5 mM KCl (K5 conditions). Granule cells cultured under these conditions express high levels of mGlu1 receptors (Pshenichkin et al., 2008).

2.3 – Cell viability assays

Cell viability was measured by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay where formation of the colored product is proportional to the number of viable cells (Mosmann, 1983). Cerebellar granule cells were maintained for 5 days in vitro in culture media, and then media was removed and replaced with 200 μl K5 media containing drugs in 1% DMSO. Neurons were incubated with drugs overnight. The next day, 50 μl of 1.5 mg/ml MTT in K5 media was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. MTT was then removed and the colored formazan product was dissolved in 65 μl/well DMSO. Absorbance of each well was measured at 570 nm by spectrophotometer (EnVision, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell viability is expressed as either percent of K25 (positive control), or as percent of glutamate efficacy.

2.4 – Measurement of PI hydrolysis

PI hydrolysis was measured using scintillation proximity assay (SPA) beads as previously described (Emery et al., 2010). After 6-7 days in vitro, culture media was replaced with K5 media containing 0.625 μCi/well myo-[3H]inositol (Perkin Elmer) and incubated overnight. Media was then removed and cells were treated with drugs in 0.5% DMSO for 1 hour at 37°C in 100 μl/well Locke’s buffer (156 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 3.6 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 5.6 mM glucose and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) with 20 mM LiCl to block the degradation of inositol phosphates. Drug treatments were then removed and inositol phosphates were extracted in 60 μl/well ice cold 10 mM formic acid for 30 minutes. 40 μl/well were then transferred to a scintillation plate containing 1 mg/well YSi poly-lysine SPA beads (Perkin-Elmer) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with vigorous shaking. After 10 hours of incubation with SPA beads, inositol phosphates were detected by scintillation counting.

2.5 – Stability of agonists in media

Agonists were bioassayed after 24-hour exposure to cerebellar granule cells to establish prolonged stability. Agonists were “cultured conditioned” by incubating agonists in K5 media with cerebellar granule cells for 24 hours. Culture conditioned agonists in K5 media were collected, 20 mM LiCl was added, and agonist were applied to separate cultures of cerebellar granule cells that were previously labeled with 0.625 μCi/well myo- [3H]inositol. Resulting PI hydrolysis in response to culture conditioned agonists was compared in parallel to PI hydrolysis caused by agonists freshly prepared in K5 media with 20 mM LiCl.

2.6 – Curve fittings and statistical analysis

Dose-response curves were modeled via four-parameter nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 6 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). For each agonist the bottom parameter was constrained to the corresponding basal value (K5 for viability, Locke for PI hydrolysis). Differences between dose-response curves were determined by comparing Emax and EC50 values, for experiments with data that could not be fit to the non-linear regression model significant effects were determined by comparing one maximal concentration of ligand to basal levels. Each experiment was performed at least two times using independent preparations of granule cells, with measurements taken in duplicate within each experiment. Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05 by Student’s t-test or Sidak-corrected multiple comparisons following one- or two-way ANOVA. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software.

3. Results

3.1 – Glutamate increases viability of granule cells in K5 conditions via activation of mGlu1 receptors

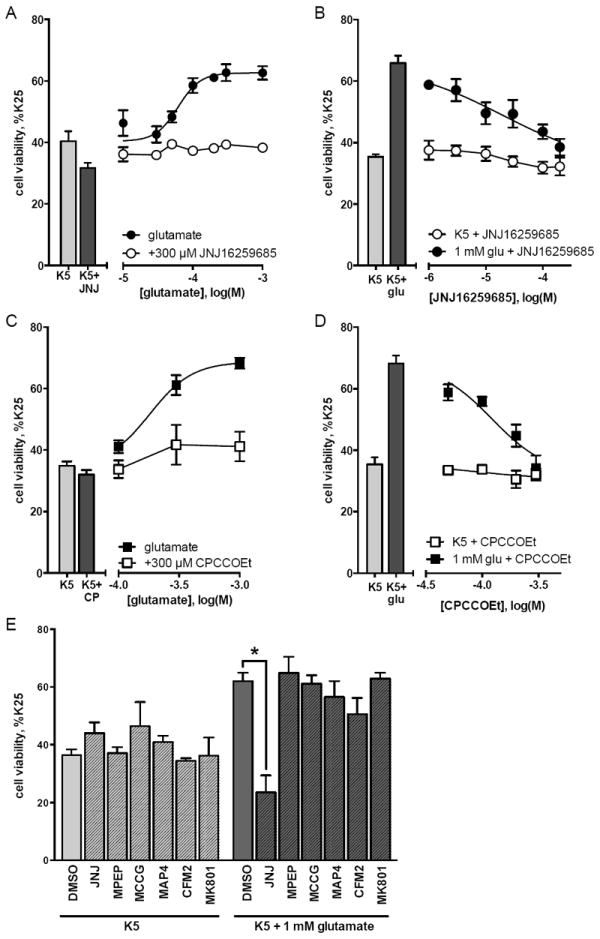

To maximize cell viability, primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons are maintained in media supplemented with high potassium (K25) (Gallo et al., 1987). Decreasing potassium to 5 mM (K5) reduced granule cell viability and after 16 hours the amount of viable cells in K5 cultures was approximately 35% of that in K25 cultures (Figure 1). Addition of glutamate to K5 media caused a concentration-dependent increase in granule cell viability, with an EC50 of 76 μM and a maximum effect of 65% of the viability observed in K25 cultures (p<0.001 compared to K5). This increase in cell viability with glutamate treatment was significantly blocked by the mGlu1 receptor noncompetitive antagonist JNJ16259685 (300 μM, Figure 1A; p=0.004), with an IC50 of 19.8 μM (Figure 1B) and by the mGlu1 receptor noncompetitive CPCCOEt (300 μM, Figure 1C; p=0.007) with an IC50 of 123 μM (Figure 1D). However, the increase in granule cell viability mediated by 1 mM glutamate was not significantly reduced by antagonism of mGlu5 receptors (10 μM MPEP), group II mGlu receptors (100 μM MCCG), group III mGlu receptors (100 μM MAP4), AMPA receptors (10 μM CFM2), or NMDA receptors (1 μM MK801) (Figure 1E). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that the glutamate-dependent increase in viability of granule cells in K5 is specifically mediated by activation of mGlu1 receptors.

Figure 1. Glutamate increases viability of cerebellar granule cells in K5 via mGlu1 receptor activation.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 5 days in vitro and then subjected to potassium withdrawal for 16 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Drugs were added to K5 at the time of potassium withdrawal. (A) Addition of glutamate to K5 conditions increased cell viability and this neuroprotective effect of glutamate was inhibited by addition of the mGlu1 receptor-selective noncompetitive antagonist JNJ16259685 (300 μM). (B) Addition of JNJ16259685 to a maximal concentration of glutamate (1 mM) resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease in the neuroprotective action of glutamate, with an IC50 of 19.8 μM. (C-D) The neuroprotective effect of glutamate was also inhibited by the mGlu1 receptor noncompetitive antagonist CPCCOEt (300 μM), with an IC50 of 123 μM. (E) The glutamate-induced increase in granule cell viability was not affected by antagonists to mGlu5 receptors (MPEP, 10 μM), group II mGlu receptors (MCCG, 100 μM), group III mGlu receptors (MAP4, 100 μM), AMPA receptors (CFM2, 10 μM), or NMDA receptors (MK801, 1 μM). All data are represented as percent of K25 control and are means of at least 3 independent experiments with error bars corresponding to S.E.M. Statistical significance defined as p<0.05 (*) by ANOVA followed by Sidak post-test to account for multiple comparison.

3.2 – Increase in viability of K5 cultures with NMDA treatment requires mGlu1 receptor activation and extracellular glutamate

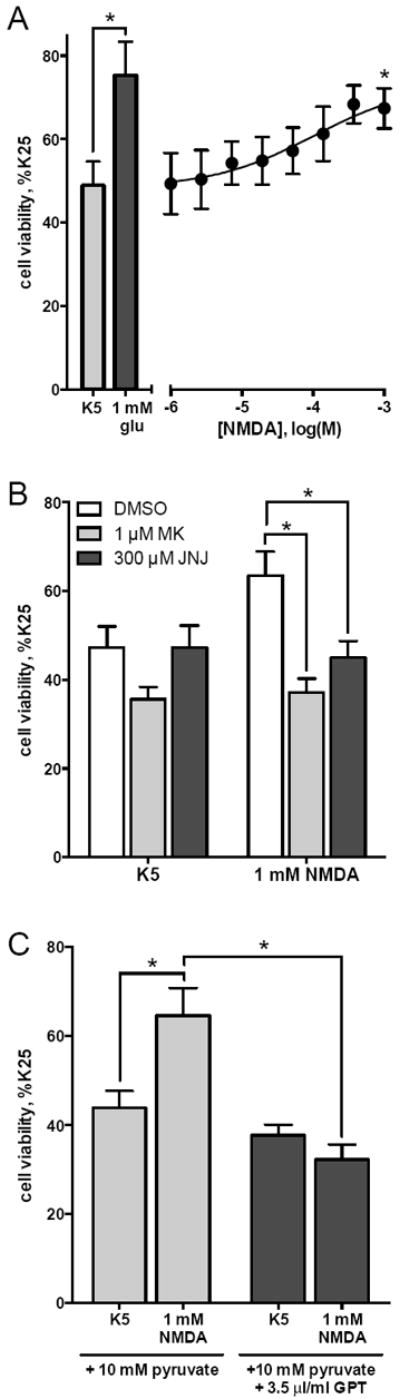

We found that NMDA receptor antagonism did not significantly reduce glutamateinduced protection from K5 toxicity, although there are numerous previous studies reporting that application of NMDA increases viability of granule cells cultured in K5 conditions (Balázs et al., 1988; Copani et al., 1995; Xifró et al., 2014). To address this issue, we tested the ability of NMDA to increase the viability of cerebellar granule cells in K5 cultures. In agreement with previous reports, NMDA caused a concentration-dependent increase in granule cell viability with an EC50 of 106 μM and an Emax of 73% of the cell viability in K25 cultures (p=0.02 compared to K5, Figure 2A). The increase in granule cell viability mediated by 1 mM NMDA was significantly inhibited by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 (1 μM) (Figure 2B). Additionally, the effect of NMDA was blocked by mGlu1 receptor antagonism (300 μM JNJ16259685, Figure 2B). These data imply that the protection mediated by NMDA requires activation of both NMDA receptors and mGlu1 receptors. One possible explanation of this result is that NMDA receptor stimulation induces depolarization of granule neurons, resulting in release of glutamate that subsequently activates mGlu1 receptors. To test this, 1 mM NMDA in K5 was co-applied with glutamate pyruvate transaminase (GPT). In the presence of high concentrations of pyruvate, GPT enzymatically converts glutamate and pyruvate to α-ketoglutarate and alanine, thus effectively depleting extracellular glutamate. Addition of 1 mM NMDA to K5 significantly increased granule cell viability in the presence of 10 mM pyruvate, however NMDA was no longer effective in the presence of 10 mM pyruvate + 35 μg/ml GPT (Figure 2C). These results indicate that NMDA treatment increases the viability of granule cells in K5 due to an NMDA receptor-mediated increase in extracellular glutamate, which then activates mGlu1 receptors. This further supports the conclusion that glutamate-stimulated protection from decreased granule cell viability upon potassium withdrawal does not appear to involve NMDA receptors, but instead specifically requires mGlu1 receptor activation.

Figure 2. Increase in viability of granule cells in K5 with NMDA treatment requires NMDA receptors, mGlu1 receptors, and extracellular glutamate.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 5 days in vitro and then subjected to decreased potassium conditions (K5) for 16 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Drugs were added to K5 at the time of potassium withdrawal. (A) Addition of NMDA to K5 conditions increases granule cell viability (Emax: 72% of K25 control, EC50: 105.5 μM). (B) NMDA effect is inhibited by both antagonism of either NMDA receptors (MK801, 1 μM) or mGlu1 receptors (JNJ16259685, 300 μM). (C) Enzymatic depletion of extracellular glutamate (using glutamate pyruvate transaminase, GPT) also inhibited NMDA protection from K5 toxicity. Data are means of at least 3 independent experiments with error bars corresponding to S.E.M. Statistical significance defined as p<0.05 (*) by ANOVA followed by Sidak post-test to account for multiple comparisons.

3.3 – Only a subset of mGlu1 receptor agonists protect cerebellar granule cells from K5 toxicity

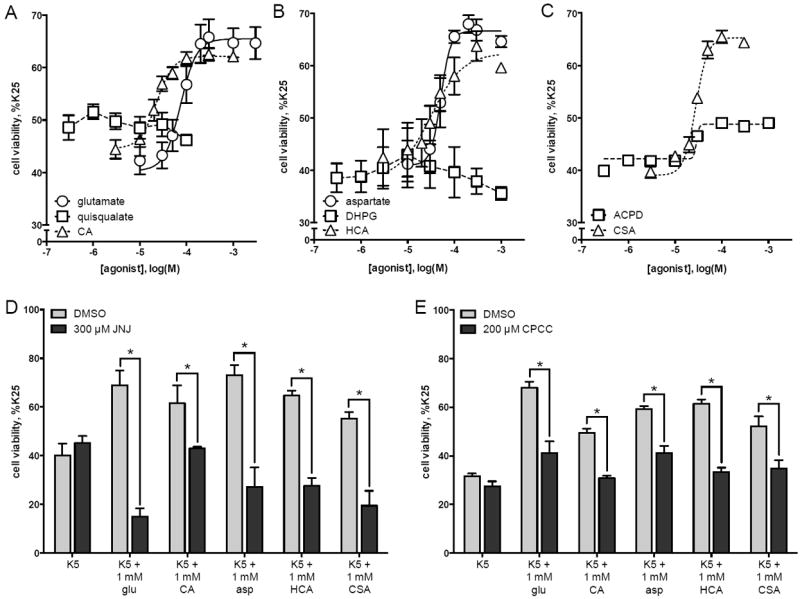

Having established a role of mGlu1 receptor stimulation in increasing the viability of cerebellar granule cells, we next performed a thorough characterization of the pharmacology of this effect using multiple mGlu1 receptor agonists. Similar to glutamate (Figure 3A, round symbols), addition of other endogenous compounds (Shi et al., 2003) increased viability of granule cells in K5 conditions. Addition of aspartate to K5 media significantly increased granule cell viability (Figure 3B, round symbols; p<0.001). The sulfinic acid analog of aspartate, cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA), also increased viability of granule cells in K5 (Figure 3C, triangle symbols; p<0.001), as did the related compounds cysteic acid (CA, Figure 3A, triangle symbols; p<0.001) and homocysteic acid (HCA, Figure 3B, triangle symbols; p<0.001). We also tested three exogenous agonists commonly used to study mGlu1 receptors: quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD. Neither quisqualate (Figure 3A, square symbols) nor DHPG (Figure 3B, square symbols) increased viability of granule cells in K5 and dose-response curves could not be fit to these data. Addition of ACPD to K5 caused a small increase in granule cell viability and this response could be fit to a dose-response curve (Figure 3C, square symbols); however the maximum efficacy of ACPD was not a significant increase compared to K5 alone (49 ± 5% with ACPD compared to 42 ± 4% in K5, p=0.23).

Figure 3. Characterization of ability of mGlu1 receptor agonists to protect cerebellar granule cells from K5 toxicity.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 5 days in vitro and then subjected to decreased potassium conditions (K5) for 16 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Drugs were added to K5 at the time of potassium withdrawal. Cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay and is expressed as a percent of viability of cells cultured in K25 media. K5-induced toxicity was prevented by treatment with (A) glutamate, cysteic acid, (B) aspartate, homocysteic acid, and (C) cysteine sulfinic acid. Viability of cerebellar granule cells was not significantly increased by (A) quisqualate, (B) DHPG, or (C) ACPD. Agonist-dependent increases in cell viability were significantly inhibited by the mGlu1 receptor antagonists JNJ16259685 (300 μM, panel D) or CPCCOEt (200 μM, panel E). Data are means of at least 3 independent experiments with error bars corresponding to S.E.M. Statistical significance defined as p<0.05 (*) by ANOVA followed by Sidak post-test to account for multiple comparisons.

For each agonist that increased viability of granule cells in K5 conditions, a maximal concentration of agonist was assayed in the presence of 300 μM JNJ16259685 (Figure 3D) or in the presence of 200 μM CPCCOEt (Figure 3E). These mGlu1 receptor antagonists significantly blocked the increase in granule cell viability induced by 1 mM glutamate, 1 mM CA, 1 mM aspartate, 1 mM HCA, and 1 mM CSA (Figure 3D-E).

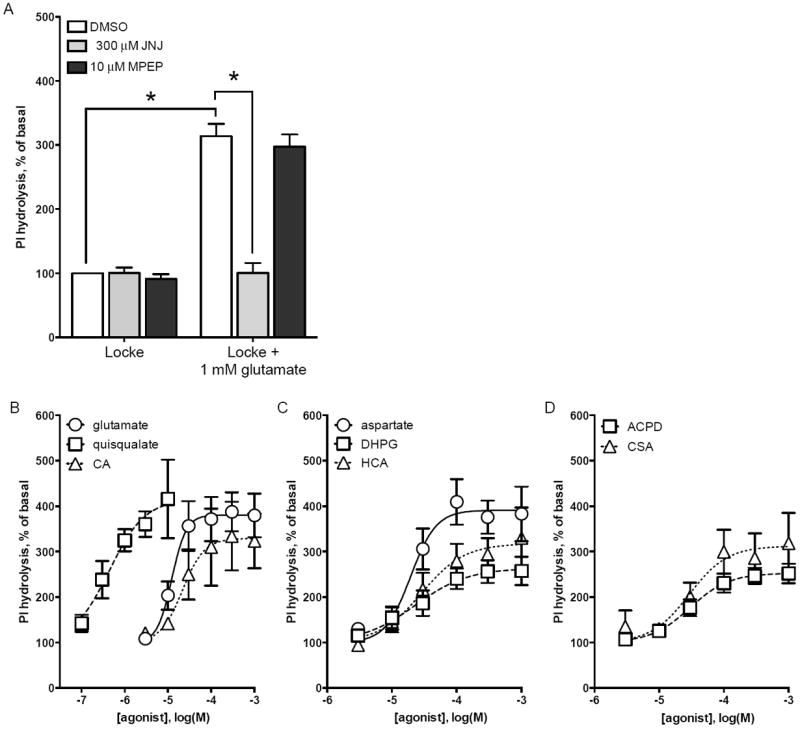

3.4 – mGlu1 receptors exhibit biased agonism in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells

Only a subset of ligands that activate mGlu1 receptors protected cerebellar granule cells from K5 toxicity; however, in previous reports these non-protective ligands stimulate PI hydrolysis in neurons (Schoepp et al., 1994; Toms et al., 1995). This suggests that biased agonism may exist at mGlu1 receptors. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of these non-protective compounds to activate mGlu1 receptor-mediated PI hydrolysis. In cerebellar granule cells maintained overnight in K5 conditions, addition of 1 mM glutamate caused a robust increase in PI hydrolysis compared to granule cells treated with DMSO vehicle (314% of basal, p<0.001; Figure 4A). This increase in PI hydrolysis was completely inhibited by the mGlu1 receptor antagonist JNJ16259685 (300 μM), and was not affected by the mGlu5 receptor antagonist MPEP (10 μM) (Figure 4A). These data suggest that mGlu1 receptor stimulation is solely responsible for glutamatedependent PI hydrolysis in cerebellar granule cells.

Figure 4. Characterization of mGlu1 receptor agonist-mediated PI hydrolysis in cerebellar granule cells.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 6-7 days in vitro and then membrane phosphoinositides were labeled by overnight incubation in K5 plus 3Hinositol. K5 media was then removed and PI hydrolysis was measured in response to agonists and antagonists diluted in Locke’s medium containing 0.5% DMSO vehicle. (A) Addition of 1 mM glutamate caused a robust increase in PI hydrolysis in cerebellar granule cells. Glutamate-induced PI hydrolysis was inhibited by mGlu1 receptor-selective antagonist JNJ16259685 but not by mGlu5 receptor antagonist MPEP. PI hydrolysis was increased in a dose-dependent manner by (B) glutamate, quisqualate, cysteic acid, (C) aspartate, DHPG, homocysteic acid, (D) ACPD, and cysteine sulfinic acid. Data are means ± S.E.M. of 3 independent experiments (panel A) or means ± S.D. of at least 2 independent experiments (panels B-D). Statistical significance defined as p<0.05 (*) by ANOVA followed by Sidak post-test to account for multiple comparisons.

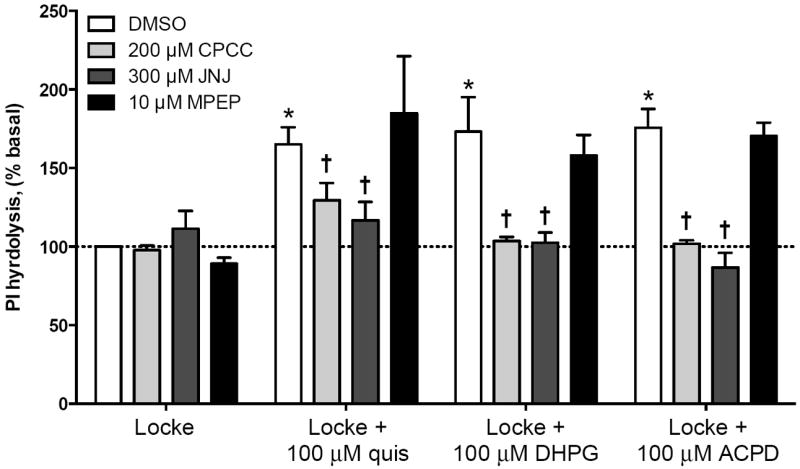

Having established that mGlu1 receptor activation stimulates PI hydrolysis, we next assayed PI hydrolysis in response to a panel of compounds. All five neuroprotective agonists increased PI hydrolysis: glutamate (Figure 4B, round symbols), aspartate (Figure 4C, round symbols), cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA, Figure 4D, triangle symbols), cysteic acid (CA, Figure 4B, triangle symbols), and homocysteic acid (HCA, Figure 4C, triangle symbols). Additionally, the non-protective ligands quisqualate (Figure 4B, square symbols), DHPG (Figure 4C, square symbols), and ACPD (Figure 4D, square symbols) increased PI hydrolysis. Quisqualate was as a full agonist while DHPG and ACPD were partial agonists compared to glutamate. To confirm that PI hydrolysis elicited by quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD is due to mGlu1 receptor activation each agonist was assayed in the presence of JNJ16259685 or CPCCOEt (Figure 5, grey bars). Both of these mGlu1 receptor antagonists significantly decreased PI hydrolysis stimulated by quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD. Additionally, the mGlu5 receptor antagonist MPEP had no effect on agonist-stimulated PI hydrolysis (Figure 5, black bars). These data confirm that the ligands investigated in this study act as mGlu1 receptor agonists in cerebellar granule cell cultures.

Figure 5. PI hydrolysis induced by mGlu receptor-selective agonists is due to mGlu1 receptor activation in cerebellar granule cells.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 6-7 days and then membrane phosphoinositides were labeled by overnight incubation in K5 plus 3H-inositol. K5 media was then removed and PI hydrolysis was measured in response to agonists and antagonists diluted in Locke’s medium containing 0.5% DMSO. Addition of quisqualate (quis, 100 μM), DHPG (100 μM), or ACPD (100 μM) induced a significant increase in PI hydrolysis compared to granule cells treated in Locke’s media only (white bars). PI hydrolysis induced by all three agonists was significantly decreased by the mGlu1 receptor antagonists JNJ16259685 (JNJ, 300 μM – dark grey bars) or CPCCOEt (CPCC, 200 μM – light grey bars). Agonist-induced PI hydrolysis was not significantly diminished by mGlu5 receptor antagonism (MPEP, 10 μM – black bars). Dashed line corresponds to basal PI hydrolysis in Locke + 0.5% DMSO vehicle. Data are means of at least 3 independent experiments with error bars corresponding to S.E.M. Statistical significance defined as p<0.05 when compared to Locke + DMSO (*) or when compared to Locke + agonist (†) by ANOVA followed by Sidak post-test to account for multiple comparisons.

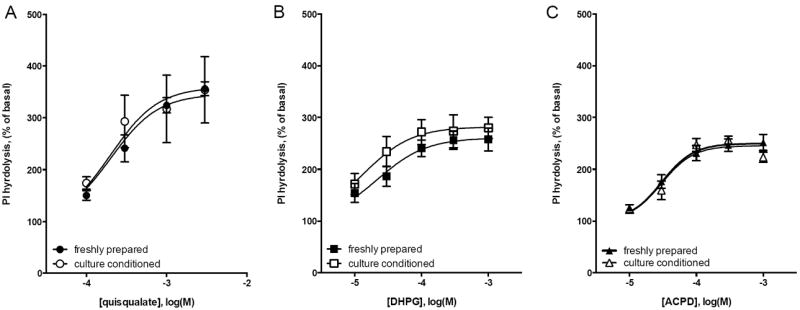

One possible reason quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD cause mGlu1 receptormediated PI hydrolysis in cerebellar granule cells but do not protect from K5 toxicity is that these drugs degrade over time. Viability experiments require overnight incubation while assay of PI hydrolysis requires only a short incubation with agonist (1 hour). To test the hypothesis that these non-protective mGlu1 receptor ligands have a decreased stability over time, agonists were incubated with cerebellar granule cells in K5 media overnight. This culture conditioned media was then removed and added to untreated cultures of cerebellar granule cells. If prolonged incubation decreased agonist stability, then PI hydrolysis stimulated by culture conditioned agonists (Figure 6, open symbols) would be less than that stimulated by agonists freshly prepared in K5 media (Figure 6, closed symbols). However, we found that overnight incubation with cerebellar granule cells had no significant effect on the EC50 or Emax for PI hydrolysis stimulated by quisqualate (Figure 6A), DHPG (Figure 6B), or ACPD (Figure 6C). Thus, the inability of these agonists to protect cerebellar granule cells from K5 toxicity cannot be explained by a loss of agonist stability.

Figure 6. Quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD are not labile when incubated overnight.

Cerebellar granule cells were maintained in K25 media for 6-7 days in vitro and then incubated overnight with agonists in K5 media. The following day, culture conditioned agonists in K5 media were used to stimulate PI hydrolysis in parallel cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Results with conditioned media (closed symbols) are compared with PI hydrolysis in response to agonists freshly prepared in CO2-saturated K5 media (open symbols). There was no change in efficacy or potency for (A) quisqualate, (B) DHPG, and (C) ACPD in stimulating PI hydrolysis after overnight incubation with cerebellar granule cells. Data are means from 3 independent experiments with error bars representing S.E.M.

The EC50 and Emax values for the eight mGlu1 receptor ligands tested in this study are presented in Table 1. The rank order of potency for PI hydrolysis is quisqualate ≫ glutamate ≈ aspartate ≈ CA ≈ DHPG ≈ HCA ≈ CSA ≈ ACPD; for increased cell viability in K5 conditions, the rank order of potency is CA ≈ CSA ≈ HCA > aspartate ≈ glutamate. While the sulfur-containing compounds (HCA, CA, CSA) have similar EC50 values for both assays, glutamate and aspartate are both more potent in inducing PI hydrolysis. This difference in potency for glutamate and aspartate may be explained by uptake of these compounds via excitatory amino acid transporters (Velaz-Faircloth et al., 1996) during the long incubation period required for cell viability experiments, resulting in a decreased effective agonist concentration and thus lower EC50. In support of this hypothesis, the apparent amount of glutamate in K5 media was reduced after overnight incubation with granule cell cultures (Supplemental Figure 1). On the other hand, EC50 values could not be calculated for quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD as these compounds did not significantly increase viability of granule cells in K5 conditions. While quisqualate is extremely potent in stimulating PI hydrolysis, it has no efficacy for protection from K5 toxicity, even at concentrations greater than 200 times its EC50 for PI hydrolysis. Similarly, neither DHPG nor ACPD caused a significant increase in granule cell viability in K5 conditions, but both stimulated PI hydrolysis. It is interesting to note that all the endogenous compounds tested stimulated both responses, whereas the exogenous compounds only stimulated PI hydrolysis.

Table 1. Summary of Emax and EC50 values for two mGlu1 receptor-mediated responses in cerebellar granule cells.

Data are summaries of those presented in figure 3 (increased granule cell viability in K5 cultures), and figure 4 (PI hydrolysis). For each agonist, efficacy is represented as a percentage of the efficacy of glutamate, the endogenous mGlu1 receptor agonist. N.D. (not determined) is used when an agonist had no significant efficacy and thus EC50 values could not be calculated. Values are calculated using data from at least 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate and are presented as mean +/- 95% confidence interval.

| Neuroprotection | PI hydrolysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist | Emax, % glu | EC50, μM | Emax, % glu | EC50, μM |

| Glutamate | 100 ± 9.9 | 76 (52 - 111) | 100 ± 2.6 | 12 (11 - 14) |

| Aspartate | 101 ± 8.7 | 51 (40 - 65) | 103 ± 7.8 | 19 (12 - 32) |

| Cysteic acid | 94 ± 7.3 | 23 (18 - 29) | 87 ± 4.2 | 22 (15 - 30) |

| Homocysteic acid | 95 ± 12 | 31 (14 - 69) | 84 ± 7.4 | 29 (14 - 58) |

| Cysteine sulfinic acid | 99 ± 7.5 | 28 (25 - 31) | 82 ± 10 | 29 (11 - 58) |

| Quisqualate | N.D. | N.D. | 109 ± 7.8 | 0.44 (0.13 - 1.5) |

| DHPG | N.D. | N.D. | 69 ± 3.7 | 23 (14 - 37) |

| ACPD | N.S. | N.D. | 66 ± 1.4 | 30 (28 - 32) |

N.D. = not detected

N.S. = not significant

4. Discussion

It is becoming increasingly apparent that GPCR signaling is more complex than the canonical activation of a G protein. An increasing number of GPCRs, including mGlu1 receptors, are reported to couple to multiple G proteins and non-G protein transducers. mGlu1 receptors originally were reported to increase phospholipase C activity (Houamed et al., 1991; Masu et al., 1991) by coupling with Gq/11 and/or with Gi/o (Selkirk et al., 2001). In heterologous systems, mGlu1 receptors also stimulate G protein-independent responses, including β-arrestin-dependent signaling (Emery et al., 2012, 2010). However, while G protein signaling and PI hydrolysis has been confirmed in neurons, alternative signaling mediated by mGlu1 receptors in native systems is not well described (Ferraguti et al., 2008). In this study we characterize mGlu1 receptor signaling using two methods and multiple ligands in the physiologically relevant model of cerebellar granule cells.

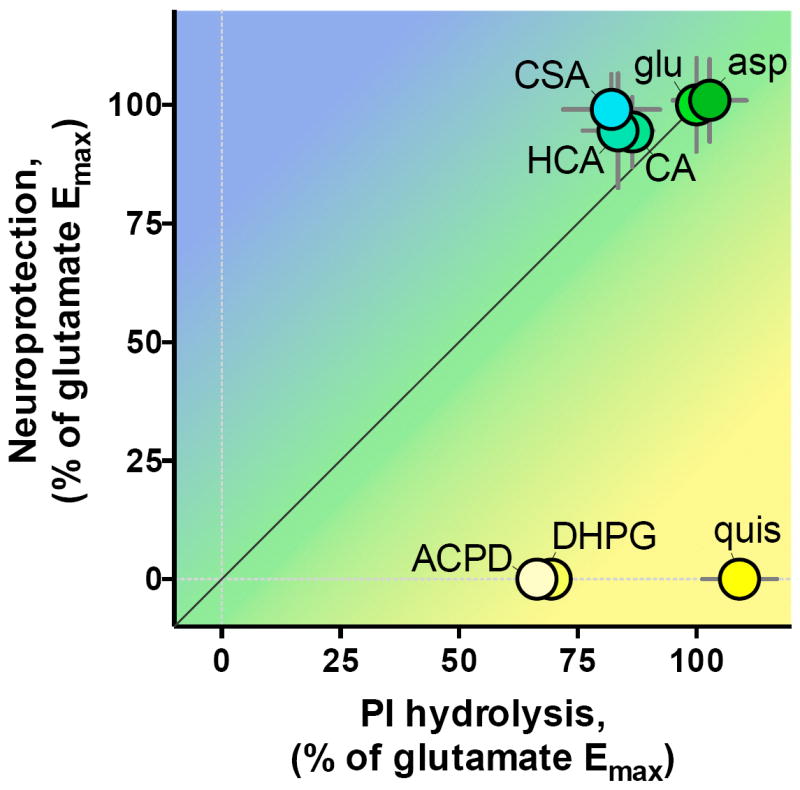

Stimulation of granule cells with glutamate increases PI hydrolysis and also protects granule cells from low potassium-induced toxicity. Both of these actions require mGlu1 receptor activation, as both responses were blocked with mGlu1 receptor antagonists but were unaffected by other glutamate receptor antagonists. In contrast to glutamate, some mGlu1 receptor ligands (quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD) stimulated PI hydrolysis, but were unable to protect granule cells from decreased viability after potassium removal. Thus these ligands are mGlu1 receptor agonists that are completely biased towards PI hydrolysis. On the other hand glutamate, aspartate, CA, HCA, and CSA were balanced agonists with equal efficacies for both responses (Figure 7). To our knowledge, this study is the first demonstration of bias agonism of a class C GPCR in a native system.

Figure 7. Biased agonism of mGlu1 receptors in cerebellar granule cells.

Cartesian representation of relative efficacy for neuroprotection from K5 toxicity (y-axis) versus relative efficacy for PI hydrolysis (x-axis). Coordinates are from Emax values in Table 1 Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Biased agonism may be explained by distinct coupling of mGlu1 receptors with different transducers based on the bound ligand. This is supported by emerging modifications to receptor theory wherein a GPCR has numerous “active” states, with certain ligand-bound receptor confirmations favoring one transducer/pathway over another (Reiter et al., 2012). In this case, a biased agonist is one that preferentially stabilizes specific receptor-transducer complexes, i.e. an agonist that has different molecular efficacies for different transducer systems (Strachan et al., 2014). Additionally, the transducer itself plays a role in receptor conformation and resulting signal transduction. Thus, cell- and tissue-dependent changes in transducer availability can change the signaling profile of a receptor (Maudsley et al., 2005). Therefore it is vital that receptor responses are measured in native systems using endogenous agonists, when possible, to fully assess the physiological function of a receptor.

It is interesting to note that the IC50 values for both mGlu1 receptor antagonists used in this study were substantially higher than previously published results (JNJ16259685: 19.8 μM in this study versus 1.7 nM (Lavreysen et al., 2004). CPCCOEt: 123 μM in this study versus 9.9 μM (Lavreysen et al., 2004; Litschig et al., 1999)). It is important to emphasize that these previously reported IC50 values were calculated based on antagonist ability to block agonist-induced PI hydrolysis, whereas the IC50 values reported in this study were calculated based on antagonist inhibition of glutamatedependent neuroprotection. Additionally, in a model of glutamate-dependent cell growth of two mGlu1 receptor-expressing human melanoma cell lines, the IC50 for JNJ16259685 is approximately 100 μM, as measured by cell viability (Gelb et al., 2014). Thus, it is possible that these mGlu1 receptor noncompetitive antagonists may be more potent in inhibiting mGlu1 receptor-mediated PI hydrolysis compared to mGlu1 receptor-dependent increases in cell viability. Indeed, a natural progression of the receptor theory that explains biased agonism also suggests the propensity for biased antagonism. The multidimensionality of GPCR signaling suggests there are multiple receptor confirmations that promote varied signal transduction (i.e. multiple “active” confirmations); it therefore follows that there are multiple “inactive” confirmations with antagonist binding stabilizing one or more of these states. Just as an agonist can preferentially stabilize one “active” receptor confirmation (a biased agonist) it is logical that an antagonist could also have different affinities for certain “inactive” receptor confirmations, and indeed such biased antagonism is reported for other GPCRs (Dias et al., 2011; Kenakin, 2014; Mathiesen et al., 2005). Thus, the higher IC50 values for inhibition of glutamate-stimulated neuroprotection suggests that these mGlu1 receptor antagonists may be biased towards inhibiting PI hydrolysis. This finding further emphasizes the importance of using multiple assays when characterizing receptor signaling and pharmacology.

In this study, we characterized native mGlu1 receptors in cerebellar granule cells using a panel of ligands via two assays. The first, protection from K5 toxicity, was investigated because this is a common paradigm in cerebellar granule cells (Contestabile, 2002) and because we previously reported glutamate could prevent this toxicity (Pshenichkin et al., 2008). The second, PI hydrolysis, was investigated because it is one of the most commonly used measures of mGlu1 receptor activation (Ferraguti et al., 2008). It is well established that PI hydrolysis is a result of G protein activation, but less is known about the signal transduction responsible for mGlu1 receptor-mediated protection from withdrawal of trophic support. From our studies it is obvious that mGlu1 receptor stimulation of PI hydrolysis is not sufficient to protect from K5 toxicity as some ligands that stimulate PI hydrolysis are not protective. However, the elucidation of the neuroprotective molecular mechanism is complicated by a lack of unbiased mGlu1 receptor-selective agonists. As quisqualate, DHPG, and ACPD are group I mGlu receptor preferring these ligands are commonly used to study mGlu1 receptor signaling in neurons so as to reduce effects of other glutamate receptors. Thus, much of what is known about mGlu1 receptor signaling in native systems is in response to these non-protective, PI hydrolysis-biased agonists (Ferraguti et al., 2008) and may not be applicable to the signal transduction that underlies neuroprotection.

To study the molecular mechanism responsible for mGlu1 receptor-mediated neuroprotection it would be most efficient to use agonists that are biased towards this response. In mGlu1 receptor-expressing CHO cells, we previously reported two such mGlu1 receptor ligands: glutaric acid and succinic acid. These agonists had no efficacy for PI hydrolysis but were able to protect mGlu1 receptor-expressing CHO cells from serum starvation, and thus were biased towards protection. Both agonists exhibited low potency and efficacy (relative to glutamate) (Emery et al., 2012), even though these experiments were performed in an overexpression system with significant receptor reserve (Emery et al., 2010), implying that these agonists may require occupation of a large numbers of receptors to be efficacious. This may explain why results using these ligands in neurons were inconsistent and varied greatly between preparations of granule cells (data not shown). It is possible that the effects of these low-potency ligands are only apparent when mGlu1 receptors are highly expressed, and that different preparations of granule cells express varying levels of mGlu1 receptors. Regardless, to study the protective signaling of mGlu1 receptors new, selective compounds with improved pharmacology need to be developed.

In the absence of agonists biased towards protection, the best ligands to study the neuroprotective mechanism underlying mGlu1 receptor activation are balanced agonists such as glutamate. In this study, we show that extracellular glutamate, mGlu1 receptor activation, and NMDA receptor activation are all required for the increase in granule cell viability mediated by NMDA treatment. This suggests that the protective actions of NMDA (and NMDA receptor activation) are due at least in part to release of glutamate and secondary activation of mGlu1 receptors. Thus, studies on the effect of NMDA in K5 (Contestabile, 2002) may provide a reasonable hypothesis for the signal transduction responsible for mGlu1 receptor-mediated neuroprotection. For example, addition of NMDA to cerebellar granule cells cultured in K5 conditions increases Ras activity, resulting in phosphorylation of ERK and Akt (Xifró et al., 2014). Additional evidence comes from studies in melanoma cell lines, which secrete high concentrations of glutamate (Namkoong et al., 2007). In melanoma cells, targeted downregulation of mGlu1 receptors decreases ERK and AKT phosphorylation (Wangari-Talbot et al., 2012), whereas overexpression of mGlu1 receptors increases ERK and AKT phosphorylation (Wen et al., 2014). Additionally, in transfected CHO cells, mGlu1 receptor stimulation increases ERK phosphorylation and is required for protection from toxicity after serum starvation. This increase in ERK phosphorylation is mediated via a G protein-independent, β-arrestin-dependent pathway (Emery et al., 2010) with a biased agonism profile similar to granule cells, namely that quisqualate and DHPG do not stimulate ERK phosphorylation or protection (Emery et al., 2012). These studies suggest that the anti-apoptotic signaling of mGlu1 receptors in neurons may involve stimulation of the MEK/ERK MAP kinase cascade and/or the PI3 kinase/Akt cascade via a PI hydrolysis-independent mechanism.

As we understand more about the complexity of receptor activation, it becomes overwhelmingly apparent that measuring a single readout using a single ligand provides a limited glimpse into the complete signaling profile of a receptor. Relying on one ligand and/or readout restricts our understanding of the physiological role of a receptor and thus makes selective drug design more difficult. Understanding the signaling of mGlu1 receptors in physiological systems is vital as these receptors may be involved in the pathophysiology of numerous diseases (Nicoletti et al., 2011). Notably, loss of mGlu1 receptor function may contribute to the pathology of spinocerebellar ataxias (Guergueltcheva et al., 2012; Mitsumura et al., 2011; Rossi et al., 2010), and activation of mGlu1 receptors using a positive allosteric modulator has shown therapeutic potential in ataxic mice (Notartomaso et al., 2013). These findings highlight the importance of mGlu1 receptors in cerebellar physiology and emphasize the need to fully understand the signal transduction mediated by mGlu1 receptors in native systems. Additionally, a thorough understanding of biased agonism of mGlu1 receptors may lead to the development of pathway-selective mGlu1 receptor compounds. Such selective ligands would be valuable pharmacological tools for studying receptor function, and could provide a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of diseases associated with mGlu1 receptors.

Supplementary Material

Increasing concentrations of glutamate were added to 7DIV cerebellar granule cells in K5 media and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The following day this cultured conditioned media was removed and the apparent concentration of glutamate was assayed using the Amplex Red glutamic acid assay kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and resulting fluorescence (proportional to glutamate concentration) was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative fluorescent units of culture conditioned glutamate (open symbols) are compared to the signal obtained from glutamate freshly diluted in K5 media (closed symbols). In the culture conditioned media, the signal relative to an EC50 glutamate concentration (76 μM) is equivalent to the signal obtained by 19 μM freshly prepared glutamate, as indicated by the grey arrows. For each point, background fluorescence was corrected by subtracting values derived from controls lacking glutamate. Data are means from 2 experiments with error bars representing S.D.

Highlights.

Glutamate protects cerebellar granule cells from low potassium toxicity.

Neuroprotection is mediated by activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1.

Only some agonists of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 are neuroprotective.

The biased agonists quisqualate, DHPG and ACPD have no efficacy for neuroprotection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The National Institutes of Health Grant NS37436 to JTW.

Abbreviations

- ACPD

1-Aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium

- DHPG

3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- CPCCOEt

7-(Hydroxyimino)cyclopropa[b]chromen-1a-carboxylate ethyl ester

- CA

Cysteic acid

- CSA

Cysteine sulfinic acid

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HCA

Homocysteic acid

- mGlu

Metabotropic glutamate

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PI

Phosphoinositide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balázs R, Jørgensen OS, Hack N. N-methyl-D-aspartate promotes the survival of cerebellar granule cells in culture. Neuroscience. 1988;27:437–51. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraci F, Battaglia G, Sortino MA, Spampinato S, Molinaro G, Copani A, Nicoletti F, Bruno V. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in neurodegeneration/neuroprotection: still a hot topic? Neurochem Int. 2012;61:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A. Cerebellar granule cells as a model to study mechanisms of neuronal apoptosis or survival in vivo and in vitro. Cerebellum. 2002;1:41–55. doi: 10.1080/147342202753203087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copani A, Bruno VM, Barresi V, Battaglia G, Condorelli DF, Nicoletti F. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors prevents neuronal apoptosis in culture. J Neurochem. 1995;64:101–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. β-Arrestins and Cell Signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias Ja, Bonnet B, Weaver Ba, Watts J, Kluetzman K, Thomas RM, Poli S, Mutel V, Campo B. A negative allosteric modulator demonstrates biased antagonism of the follicle stimulating hormone receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;333:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AC, DiRaddo JO, Miller E, Hathaway Ha, Pshenichkin S, Takoudjou GR, Grajkowska E, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB, Wroblewski JT. Ligand bias at metabotropic glutamate 1a receptors: molecular determinants that distinguish β-arrestin-mediated from G protein-mediated signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:291–301. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AC, Pshenichkin S, Takoudjou GR, Grajkowska E, Wolfe BB, Wroblewski JT. The protective signaling of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 Is mediated by sustained, beta-arrestin-1-dependent ERK phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26041–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti F, Crepaldi L, Nicoletti F. Metabotropic Glutamate 1 Receptor: Current Concepts and Perspectives. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:536–581. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000166.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo V, Kingsbury A, Balázs R, Jørgensen OS. The role of depolarization in the survival and differentiation of cerebellar granule cells in culture. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2203–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-02203.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb T, Pshenichkin S, Rodriguez OC, Hathaway Ha, Grajkowska E, DiRaddo JO, Wroblewska B, Yasuda RP, Albanese C, Wolfe BB, Wroblewski JT. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 acts as a dependence receptor creating a requirement for glutamate to sustain the viability and growth of human melanomas. Oncogene. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guergueltcheva V, Azmanov DN, Angelicheva D, Smith KR, Chamova T, Florez L, Bynevelt M, Nguyen T, Cherninkova S, Bojinova V, Kaprelyan A, Angelova L, Morar B, Chandler D, Kaneva R, Bahlo M, Tournev I, Kalaydjieva L. Autosomal-Recessive Congenital Cerebellar Ataxia Is Caused by Mutations in Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houamed KM, Kuijper JL, Gilbert TL, Haldeman BA, O’Hara PJ, Mulvihill ER, Almers W, Hagen FS. Cloning, expression, and gene structure of a G protein-coupled glutamate receptor from rat brain. Science. 1991;252:1318–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1656524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. What is pharmacological “affinity”? Relevance to biased agonism and antagonism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavreysen H, Wouters R, Bischoff F, Nóbrega Pereira S, Langlois X, Blokland S, Somers M, Dillen L, Lesage ASJ. JNJ16259685, a highly potent, selective and systemically active mGlu1 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:961–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litschig S, Gasparini F, Rueegg D, Stoehr N, Flor PJ, Vranesic I, Prézeau L, Pin JP, Thomsen C, Kuhn R. CPCCOEt, a noncompetitive metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 antagonist, inhibits receptor signaling without affecting glutamate binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:453–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Gesty-Palmer D. Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:305–30. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu M, Tanabe Y, Tsuchida K, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. Sequence and expression of a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 1991;349:760–5. doi: 10.1038/349760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen JM, Ulven T, Martini L, Gerlach LO, Heinemann A. Identification of Indole Derivatives Exclusively Interfering with a G Protein-Independent Signaling Pathway of the Prostaglandin D2 Receptor CRTH2. 2005;68:393–402. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010520.response. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maudsley S, Martin B, Luttrell LM. The origins of diversity and specificity in g protein-coupled receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:485–94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumura K, Hosoi N, Furuya N, Hirai H. Disruption of metabotropic glutamate receptor signalling is a major defect at cerebellar parallel fibre-Purkinje cell synapses in staggerer mutant mice. J Physiol. 2011;589:3191–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.207563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S. Molecular diversity of glutamate receptors and implications for brain function. Science. 1992;258:597–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1329206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkoong J, Shin S-S, Lee HJ, Marín YE, Wall Ba, Goydos JS, Chen S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 and glutamate signaling in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2298–305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Bockaert J, Collingridge GL, Conn PJ, Ferraguti F, Schoepp DD, Wroblewski JT, Pin JP. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: from the workbench to the bedside. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1017–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notartomaso S, Zappulla C, Biagioni F, Cannella M, Bucci D, Mascio G, Scarselli P, Fazio F, Weisz F, Lionetto L, Simmaco M, Gradini R, Battaglia G, Signore M, Puliti A, Nicoletti F. Pharmacological enhancement of mGlu1 metabotropic glutamate receptors causes a prolonged symptomatic benefit in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Mol Brain. 2013;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pshenichkin S, Dolińska M, Klauzińska M, Luchenko V, Grajkowska E, Wroblewski JT. Dual neurotoxic and neuroprotective role of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 in conditions of trophic deprivation - possible role as a dependence receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Ahn S, Rominger DH, Gowen-MacDonald W, Lam CM, Dewire SM, Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Quantifying ligand bias at seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:367–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:373–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lefkowitz RJ. Molecular mechanism of β-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:179–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PIA, Vaccari CM, Terracciano A, Doria-Lamba L, Facchinetti S, Priolo M, Ayuso C, De Jorge L, Gimelli S, Santorelli FM, Ravazzolo R, Puliti A. The metabotropic glutamate receptor 1, GRM1: evaluation as a candidate gene for inherited forms of cerebellar ataxia. J Neurol. 2010;257:598–602. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi MR, Ikonomovic S, Wroblewski JT, Grayson DR. Temporal and depolarization-induced changes in the absolute amounts of mRNAs encoding metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar granule neurons in vitro. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1207–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63041207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp DD, Goldsworthy J, Johnson BG, Salhoff CR, Baker SR. 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine is a highly selective agonist for phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1994;63:769–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk JV, Price GW, Nahorski SR, Challiss RA. Cell type-specific differences in the coupling of recombinant mGlu1alpha receptors to endogenous G protein sub-populations. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:645–56. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(00)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Savage JE, Hufeisen SJ, Rauser L, Grajkowska E, Ernsberger P, Wroblewski JT, Nadeau JH, Roth BL. L-homocysteine sulfinic acid and other acidic homocysteine derivatives are potent and selective metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:131–42. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan RT, Sun J, Rominger DH, Violin JD, Ahn S, Rojas Bie Thomsen A, Zhu X, Kleist A, Costa T, Lefkowitz RJ. Divergent transducer-specific molecular efficacies generate biased agonism at a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14211–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.548131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toms NJ, Jane DE, Tse HW, Roberts PJ. Characterization of metabotropic glutamate receptor-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in rat cultured cerebellar granule cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2824–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velaz-Faircloth M, McGraw TS, Alandro MS, Fremeau RT, Kilberg MS, Anderson KJ. Characterization and distribution of the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1 in rat brain. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C67–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangari-Talbot J, Wall Ba, Goydos JS, Chen S. Functional effects of GRM1 suppression in human melanoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1440–50. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Li J, Koo J, Shin S-S, Lin Y, Jeong B-S, Mehnert JM, Chen S, Cohen-Sola Ka, Goydos JS. Activation of the glutamate receptor GRM1 enhances angiogenic signaling to drive melanoma progression. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2499–509. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski JT, Nicoletti F, Costa E. Different coupling of excitatory amino acid receptors with Ca2+ channels in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:919–21. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xifró X, Miñano-Molina AJ, Saura Ca, Rodríguez-Álvarez J. Ras protein activation is a key event in activity-dependent survival of cerebellar granule neurons. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:8462–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.536375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Increasing concentrations of glutamate were added to 7DIV cerebellar granule cells in K5 media and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The following day this cultured conditioned media was removed and the apparent concentration of glutamate was assayed using the Amplex Red glutamic acid assay kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and resulting fluorescence (proportional to glutamate concentration) was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative fluorescent units of culture conditioned glutamate (open symbols) are compared to the signal obtained from glutamate freshly diluted in K5 media (closed symbols). In the culture conditioned media, the signal relative to an EC50 glutamate concentration (76 μM) is equivalent to the signal obtained by 19 μM freshly prepared glutamate, as indicated by the grey arrows. For each point, background fluorescence was corrected by subtracting values derived from controls lacking glutamate. Data are means from 2 experiments with error bars representing S.D.