Abstract

As a surrogate of the life cell, proteo-lipobeads are presented, encapsulating functional membrane proteins in a strict orientation into a lipid bilayer. Assays can be performed just as on life cells, for example using fluorescence measurements. As a proof of concept, we have demonstrated proton transport through cytochrome c oxidase.

Membrane proteins (MPs) are the target of about 60% of all pharmaceuticals.1 Therefore, there is a great interest in bioassays for drug screening purposes of these proteins. To assay ion transport properties the MPs need to be present within lipid bilayers. Such bioassays are mostly performed on life cells2 Proteoliposomes can be used as an alternative,3 which are unfortunately, not comparable to life cells regarding their stability or the control over the orientation of the MPs. The issue of stability was solved successfully by the development of polymerosomes4, which do not permit the oriented encapsulation of MPs. A uniform orientation of MPs is a necessary prerequisite for bioassays, particularly regarding ion transport through ion channels and transporters.

We have therefore developed proteo-lipobeads (PLBs), a biomimetic system for the oriented encapsulation of MPs in a functionally active form. PLBs are based on micrometer sized agarose beads modified with small linker molecules such as NTA (nitrilotriacetic acid) terminated CH2 chains. The MPs are bound to these chains via histidine(his)-tags, a well-established method for the oriented immobilization of MPs.7 After immobilization of the MPs, these particles are subject to dialysis in the presence of solubilized phospholipids. Thereby, MPs are reconstituted into bilayer lipid membranes (BLMs) to form PLBs. The final structure is depicted schematically in Scheme 1. Similar systems have been presented before. For instance, a seven transmembrane segment protein as well as the proximal lipid layer have been attached to paramagnetic beads using antibody technology. Proteoliposomes were then formed by dialysis with lipid micelles.5 This format, however, was designed for binding assays whereas functional assays were not presented. To show the capability of PLBs as functional assays we use cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) from P. denitrificans with the his-tag attached to subunit (SU) I.

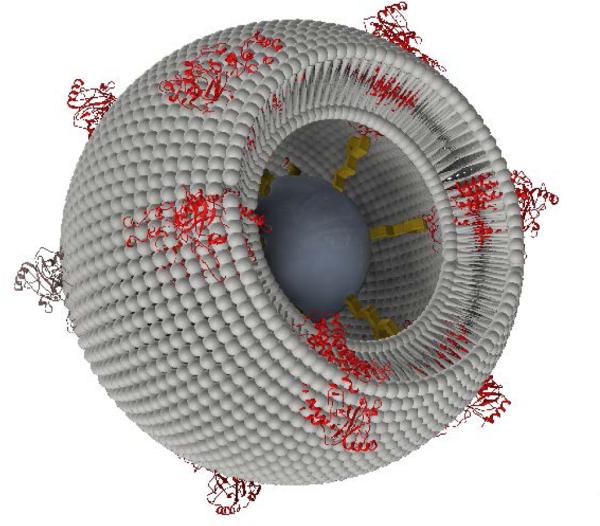

Scheme 1.

Schematic of a Proteo-Lipobead (PLB) based on an agarose bead (grey) modified by an NTA-terminated linker (yellow) with CcO (red) immobilized in strict orientation via a his-tag attached to the cytoplasmically oriented C-terminus of SU I. A DiphyPC (diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) bilayer (grey) is formed between the proteins during dialysis. The layered structure is not drawn true to scale.

The reconstitution of MPs into a BLM, thereby using the immobilized proteins as a scaffold, has been investigated previously on flat surfaces.8, 9 CcO from R. Sphaeroides with the his-tag attached to SU II was immobilized in the reverse orientation than the one used in the present study. A small aqueous layer between surface and lipid layer had been indicated indirectly by electrochemical detection of protons pumped through the CcO in the direction of the surface. An aqueous layer on both sides of the BLM is a further prerequisite for functional assays. The agarose gel used to form PLBs can be considered to provide an additional reservoir for water and ions, as shown by the accumulation of the water-soluble fluorescent dye SNARF-1, even in the presence of the lipid bilayer (Figure S2, Table S1). Hence the PLBs can be expected to provide a format not only for binding but also for functional assays. Changes of physical parameters within or in close proximity to the protein/membrane system can be monitored as a function of time using laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM).6

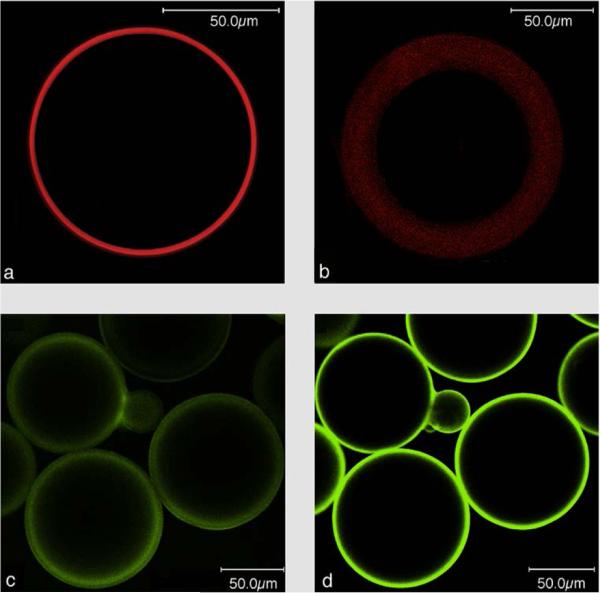

We used LSM to visualize the lipid layer of the PLBs , employing fluorescence labeled lipids such as NBD-PE as well as the potential sensitive dyes (PSDs) di-8-ANEPPS and di-4-ANBDQBS (red-shifted PSD) (Fig. 1). Formal names and excitation/emission wavelengths are given in the supplementary information Table S1. Figure 1c and 1d show the polydispersity of the PLBs ranging from 50-150 μm.

Figure 1.

Laser scanning images of PLBs labelled with NBD-PE, di-8-ANEPPS or di-4-ANBDQBS a) in the presence and b) absence of CcO. Laser scanning images taken at the equatorial plane of CcO based PLBs with a primary antibody specifically bound to SU l and SU II of CcO. A Cy5 conjugated secondary antibody was used as a fluorescent label c) in the absence and d) presence of di-4-ANBDQBS in the lipid phase.

Hemicyanine-based membrane probes like di-8-ANEPPS and di-4-ANBDQBS exhibit negligible fluorescence in aqueous solution but fluoresce strongly when bound to BLMs.10 Figure 1a illustrates a BLM layer of regular fluorescence emission intensity around the bead. BLMs are known to assemble on silica beads by themselves.11 Therefore, as a control experiment, gel beads were subjected to dialysis in the absence of immobilized CcO. Fluorescence emission can be seen in the presence of di-4-ANBDQBS, however, broader and more blurry than the BLM in the presence of immobilized MPs (Figure 1b). All of the images discussed so far were recorded in the equatorial plane of the beads (Figure S3a). Laser scanning images with the focal plane adjusted to the top of the PLB showed a continuous fluorescence of smaller diameter as expected for a BLM fully enclosing the beads (Figure S3b). We concluded from these results that using CcO as a scaffold leads to well-defined lipid bilayers evenly covering the entire surface of the gel bead.

CcO immobilized with the his-tag attached to SU I is oriented with the cytochrome c (cc) binding site pointing to the outside of the membrane. A polyclonal primary Immunoglobulin G (IgG)-antibody from rabbit specific to both SU I and II was bound to the PLBs. Subsequently, a Cy5 conjugated secondary antibody was bound to the primary IgG and the Cy5 label was excited by a HeNe laser at 633 nm. The presence of CcO was indicated by the fluorescence of the Cy5 label in the presence and absence of di-4-ANBDQBS (Figure 1c, d).

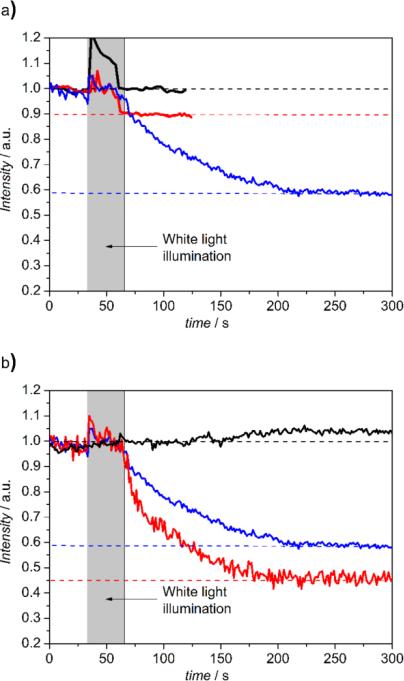

Finally, a functional assay was conducted considering, that CcO, as the terminal complex of the respiratory chain, converts the free enthalpy gained by the reduction of oxygen to water into a difference in electrochemical potentials of protons, across the lipid membrane. consists of the membrane potential, ΔΦ, and a difference in pH values, ΔpH, between the inner and outer aqueous phase. In our case, the cc binding site is located at the outer side of the PLB. Proton transport can be initiated by light activation of photoactive electron donors bound to the cc binding site that inject electrons into the CcO. In this work we used the Ru complex Ru2C ([(bpy)2Ru(diphen)Ru(bpy)2](PF6)4) as electron donor, mixed with aniline as a sacrificial electron donor and 3CP (3-carboxy-PROXYL) to prevent proton release from aniline.12 pH changes at the outside of the PLB can be conveniently detected by fluorescein DHPE (Table S1), a sensor molecule that incorporates into the distal leaflet of the lipid bilayer under the conditions described in the supporting information. A decrease of pH can be detected by a decrease of fluorescence intensity. LSM images and fluorescence intensities were recorded within localized areas before and after continuous illumination with a halogen lamp in the presence and absence of Ru2C, 3CP and aniline (Figure S5). As shown in Figure 3, fluorescence intensities decrease in a time scale of seconds by 10 % and 42 % in the buffered and unbuffered KCl solution, respectively. This effect was abolished under uncoupling conditions in the presence of valinomycin and FCCP (carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone), which render the membrane permeable to potassium ions and protons, respectively whereas in the presence of valinomycin alone the intensity dropped by 55 % due to the collapse of the membrane potential.

This behaviour is characteristic for an active transporter strongly affected by the membrane potential. Time-resolved measurements of proton release have been reported, occurring in the time scale of μs to ms, using CcO reconstituted in liposomes.12,13 These results, however, are not directly comparable with our work, because single laser flashes were used for excitation. Moreover, further work reported in a separate publication leads us to believe that the turnover rate is changed in PLBs. Note in this context, that fluorescein DHPE monitors protons in the immediate vicinity of the lipid bilayer, rather than the aqueous phase as in ref. 13. This will be investigated in more detail in a separate publication.

Conclusions

Our experiments demonstrate the applicability of PLBs as a new platform for functional assays of membrane proteins. Further work is under way using PLBs ranging in size down to the nm scale. Advantages of the new system over lipid vesicles are the uniform orientation of the incorporated proteins combined with the considerably increased stability. LSM assays shown here may be transferred easily to other formats, such as Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or Fluorescence imaging plate reader (FLIPR), which are more feasible for drug screening purposes than LSM.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

a) Time dependent change of the relative fluorescence intensity of membrane bound fluorescein DHPE before and after continuous illumination with a halogen lamp with Ru2C, 3CP and aniline in 40 mM KCl solution (blue) compared to the same PLBs with (red) and without (black) Ru2C, 3CP and aniline in Tris-HCl/KCl (5 mM/35 mM) buffer. b) Time dependent change of the relative fluorescence intensity of membrane bound fluorescein DHPE before and after continuous illumination with a halogen lamp with Ru2C, 3CP and aniline in 40 mM KCl solution (blue) in presence of valinomycin alone(red) and valinomycin and FCCP (black).

Acknowledgments

The research was supported under the Austrian Federal Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology (GZ BMVIT-612.166/0001-III/I1/2010) and the City of Vienna (MA 7). Partial support for this work was provided by ZIT, Center of Innovation and Technology of Vienna. L.M. Loew acknowledges support by NIH grant R01 EB001963. B. Durham acknowledges support by NIH grant P30 GM103450. We acknowledge the assistance of Prof. Michael Boersch, University of Jena, Germany, in the field of LSM.

Footnotes

Proteo-Lipobeads: European Patent pending, Nr. 12198401.7

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Formal names and excitation/emission wavelengths of fluorescence labels. Details of the preparation protocol, additional LSM images demonstrating the polydispersity and stability of the PLBs, See DOI: 10.1039/c000000x/

References

- 1.Yildirim MA, Goh K-I, Cusick ME, Barabasi A-L, Vidal M. Nat Biotech. 2007;25:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/nbt1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez JE, Oades K, Leychkis Y, Harootunian A, Negulescu PA. Drug Discovery Today. 1999;4:431–439. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordlund G, Ng JBS, Bergstrom L, Brzezinski P. Acs Nano. 2009;3:2639–2646. doi: 10.1021/nn9005413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May S, Andreasson-Ochsner M, Fu Z, Low YX, Tan D, de Hoog H-PM, Ritz S, Nallani M, Sinner E-K. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013;52:749–753. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirzabekov T, Kontos H, Farzan M, Marasco W, Sodroski J. Nature Biotechnology. 2000;18:649–654. doi: 10.1038/76501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claxton NS, Fellers TJ, Davidson MW. Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy Bios Scientific Publishers. Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trammell SA, Wang LY, Zullo JM, Shashidhar R, Lebedev N. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2004;19:1649–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giess F, Friedrich MG, Heberle J, Naumann RL, Knoll W. Biophysical Journal. 2004;87:3213–3220. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kibrom A, Roskamp RF, Jonas U, Menges B, Knoll W, Paulsen H, Naumann RLC. Soft Matter. 2011;7:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fluhler E, Burnham VG, Loew LM. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5749–5755. doi: 10.1021/bi00342a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimhult E, Zach M, Hook F, Kasemo B. Langmuir. 2006;22:3313–3319. doi: 10.1021/la0519554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belevich I, Bloch DA, Belevich N, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:2685–2690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608794104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirchberg K, Michel H, Alexiev U. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:8187–8193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.