Abstract

MEF2s are pleiotropic transcription factors (TFs) which supervise multiple cellular activities. During the cell cycle, MEF2s are activated at the G0/G1 transition to orchestrate the expression of the immediate early genes in response to growth factor stimulation. Here we show that, in human and murine fibroblasts, MEF2 activities are downregulated during late G1. MEF2C and MEF2D interact with the E3 ligase F-box protein SKP2, which mediates their subsequent degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4)/cyclin D1 complex phosphorylates MEF2D on serine residues 98 and 110, and phosphorylation of these residues is an important determinant for SKP2 binding. Unscheduled MEF2 transcription during the cell cycle reduces cell proliferation, whereas its containment sustains DNA replication. The CDK inhibitor p21/CDKN1A gene is a MEF2 target gene required to exert this antiproliferative influence. MEF2C and MEF2D bind a region within the first intron of CDKN1A, presenting epigenetic markers of open chromatin. Importantly, H3K27 acetylation within this regulative region depends on the presence of MEF2D. We propose that following the initial engagement in the G0/G1 transition, MEF2C and MEF2D must be polyubiquitylated and degraded during G1 progression to diminish the transcription of the CDKN1A gene, thus favoring entry into S phase.

INTRODUCTION

In vertebrates, the family of MEF2s comprises 4 members—MEF2A, -B, -C, and -D—as well as some splicing variants (1). Common features of all MEF2 members are the MADS box (MCM1, agamous, deficiens, serum response factor) and the adjacent MEF2 domain positioned within the highly conserved amino-terminal region (1). These domains are involved in recognizing the YTA(A/T)4TAR DNA motif, in mediating the formation of homo- and heterodimers, and in the interaction with different cofactors (1). The carboxy-terminal half is much less conserved. It encompasses the transactivation domains and the nuclear localization signal (2). The different family members exhibit specific but also overlapping patterns of expression, during either embryogenesis or adult life (1, 3). MEF2s are subjected to intense supervision by environmental signals, in order to couple the gene expression signature to the organism requirements (1). MEF2s oversee the expression of several genes, depending on and in cooperation with other transcription factors (TFs) (3, 4). In addition, MEF2s can also operate as repressors of transcription when in complexes with class IIa histone deacetylases (HDACs) (5, 6, 7, 8).

The extent of genes under the influence of MEF2s justifies the pleiotropic activities and the assorted cellular responses attributed to these TFs. During development, in general, expression of MEF2 is linked to the activation of differentiation programs (1). In various scenarios, the onset of MEF2 expression coincides with the withdrawal from the cell cycle (9). Specific ablation of MEF2C in neural/progenitor cells impacts differentiation but not their survival or proliferation (10). Also, in muscle, simultaneous ablation of different MEF2s impacts differentiation of satellite cell-derived myoblasts but does not alter proliferation (11).

In oncogene-transformed fibroblasts, induction of MEF2 transcription can trigger antiproliferative responses, which are responsible for reverting the tumorigenic phenotype (7). In other contexts, MEF2s seem to be involved in sustaining rather than inhibiting cell proliferation (12). During the cell cycle, MEF2 transcriptional activities are upregulated when quiescent cells are stimulated to re-enter G1 (13). Here, they contribute to the expression of the immediate early genes in response to serum (14, 15). Paradoxically, signaling pathways elicited by growth factors, and in particular, the phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway can also repress MEF2-dependent transcription (7). This repression is exerted mainly through the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of the TFs (7).

Overall, these results suggest that, during different proliferative stages, MEF2 transcriptional activities could be subjected to multiple and complex adaptations. To better understand the contribution of MEF2s to the regulation of cell growth, in this study we investigated MEF2C and MEF2D expression, regulation, and activities during distinct phases of the cell cycle, using murine and human fibroblasts as cellular models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and reagents.

BJ/TERT cells were cultured in Earle's salts minimal essential medium (EMEM) (HyClone) completed with nonessential amino acids (NEAA; HyClone). All other cell lines were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Lonza). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Lonza). Cells expressing the inducible form of MEF2 were grown in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich)/EMEM (Life Technologies) without phenol red. For analyses of cell growth, 104 cells were seeded, and the medium was changed every 2 days.

The following chemicals were used: 20 μM LY294002 (LY), 10 μM PD9800591, 0.5 μM okadaic acid (LC Laboratories); 2.5 μM MG132, 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), 5 μM roscovitine, 3 μM PD0332991, 1 μM p38i IV, 1 μM staurosporine, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 100 nM microcystin L1, 50 μM ATP, protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (all from Sigma-Aldrich); 100 nM Torin1 (Cayman); and 20 μM SKP2in [3-(1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl)-6-ethyl-7-hydroxy-8-(piperidin-1-ylmethyl)-4H-chromen-4-one] (UkrOrgSyntez Ltd.).

Plasmid construction, transfections, retroviral/lentiviral infections, and silencing.

The pEGFPC2, pFLAG CMV5a, and pGEX-4T1 constructs expressing MEF2C, MEF2D, and SKP2 were generated by PCR and subsequent cloning, using EcoRI/SalI restriction sites (NEB). Phosphodefective (Ser-Thr/Ala) and phosphomimicking (Ser/Asp) MEF2D mutants were generated using a Stratagene QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent). The MEF2D and MEF2D S98A S110A deletion mutants were generated by PCR and cloned into pEGFPC2 and pGEX-4T1 plasmids. pWZL-Hygro-MEF2-VP16-ER, pWZL-Hygro-MEF-ΔDBD-VP16-ER, pWZL-Neo-p53DN (175H) were previously described (7). To generate pWZL-Hygro and pBABE-Puro plasmids expressing SKP2, SKP2DN, SKP2ΔDD (lacking the first 8 amino acids of the destruction domain), MEF2D-FLAG, and MEF2D-S98A/S110A, the relative cDNAs were subcloned into pWZL-Hygro and pBABE-Puro plasmids using the PCR method. The fidelity of all generated plasmids was verified by DNA sequencing.

pLKO plasmids (15897 and 274054, referred to here as 15 and 27) expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) directed against MEF2D were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. For retroviral infection, HEK293 Ampho Phoenix cells were transfected with 12 μg of plasmid DNA. After 48 h at 32°C, virions were collected and diluted as appropriate to get the same multiplicity of infection (MOI) for all genes. For lentivirus-based knockdown, HEK-293 cells were transfected with 5 μg of VSV-G, 15 μg of Δ8.9, and 20 μg of pLKO plasmids. After 36 h at 37°C, virions were collected and opportunely diluted in fresh medium. Unless otherwise specified, all transfection experiments in 293 and IMR90-E1A cells were performed with a standard calcium phosphate method. Silencing of BJ/TERT and BJ/TERT/p53DN was performed with 73 nmol of SKP2 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (GGUAUCGCCUAGCGUCUGA; Invitrogen) and 56 nmol of CDKN1A siRNAs (AGACCAGCAUGACAGAUUU; Qiagen).

Production of recombinant proteins and immunoblots.

pGEX plasmids expressing wild-type MEF2D with amino acids 1 to 190 deleted, MEF2D S98A/S110A, MEF2D S98D/S110D, full-length SKP2, and Rb with amino acids 379 to 928 deleted (16) were transformed in BL-21 bacterial cells. Recombinant protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG at 30°C for 30 min, and proteins were purified using glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Immunoblots were performed as previously described (17), and relative quantitative measurements were achieved by densitometric analysis of Western blot films, normalized to the corresponding p120 or p62/nucleoporin or CRADD (loading controls) values. Each immunoblot experiment was repeated at least twice with similar results, and each densitometric analysis refers to the figures.

Immunoprecipitation and glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown.

Cells were lysed in a hypotonic buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 2 mM EDTA; 10 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors. For each immunoprecipitation 1 μg of antibody was used.

Portions (2 μg each) of recombinant proteins were used as baits in each pulldown experiment. MEF2D-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and SKP2-GFP were obtained from transfected HEK-293 cells, lysed with a hypertonic buffer containing 300 mM NaCl in order to destroy the complexes as much as possible. Pulldown was conducted at 4°C with rotation for 2 h.

Antibodies.

Antibodies used were those against MEF2C C-17 (sc13268; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), VP16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MEF2C CB (raised against a bacterially produced segment of MEF2C [amino acids 341 to 473]), MEF2D (BD Bioscience), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), phosphorylated ERK (pERK), AKT, pAKT(Ser473), RAN, nucleoporin p62, p120 (Cell Signaling), SKP2-8D9 (Life Technologies), p21 CP74 and FLAG M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), GFP (17), CRADD (18), ubiquitin (Covance), and H3K27ac (ab4729; Abcam).

RNA extraction and quantitative qRT-PCR.

Cells were lysed using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center). A total of 1 μg of total RNA was retrotranscribed by using 100 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses were performed using Bio-Rad CFX96 and SYBR green technology (Resnova). The data were analyzed by use of a comparative threshold cycle using the β2 microglobulin gene and HPRT (encoding hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase) as normalizer genes. All reactions were done in triplicate.

Cell cycle FACS analysis and BrdU assay.

For synchronization in G0/G1, NIH 3T3 cells and BJ/TERT cells were serum starved for 48 and 72 h, respectively, and then reactivated by addition of fetal calf serum (FCS). For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, cells were fixed with ethanol (overnight), treated with 10 μg RNase A (Applichem Lifescience), and stained with 10 mg propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Data were analyzed with Flowing software (http://www.flowingsoftware.com/). For S-phase analysis, cells were grown for 3 h with 50 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). After fixation, coverslips were treated with HCl. Mouse anti-BrdU (Sigma) was used as the primary antibody. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma).

In vitro phosphorylation studies.

Cellular lysates from 2.5 million NIH 3T3 cells for each time point were obtained. Cells were lysed for 10 min in native buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.1% Triton, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], PIC, 10 mM NaFl, 5 mM NaVO4, 0.5 μM okadaic acid, 100 nM microcystin L1). Two micrograms of GST fusion proteins bound to resin in GST-binding buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 140 mM NaCl) was next added. The kinase reaction was carried out by incubating for 1 h at 30°C the glutathione-bound proteins with cellular lysates supplemented with 50 μM ATP and 1 μCi γ-ATP (Perkin-Elmer). After several washes, sample buffer was added to the beads. When the recombinant cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) were used, 250 ng of cyclin D1/CDK4 or cyclin E1/CDK2 (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with GST-MEF2D proteins.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and promoter study.

The sequence of the CDKN1A-proximal promoter (10 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream from the transcription start site [TSS]) was recovered from ENCODE. The presence of a putative MEF2 binding site was predicted using CisterZlab (http://zlab.bu.edu/∼mfrith/cister.shtml) and JASPAR (http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/) algorithms.

For each chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), 2.5 × 106 cells were used and ChIP was performed as previously described (7). Anti-MEF2C (CB), anti-MEF2C C-17, anti-MEF2D, anti-H3K27ac, and anti-FLAG M2 antibodies were used, and preimmune serum was used as an unrelated control.

Statistics.

For experimental data, a Student t test was used. A P value of 0.05 was chosen as the statistical limit of significance. Unless otherwise indicated, data in the figures are arithmetic means and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

MEF2C and MEF2D protein stability is regulated during the cell cycle.

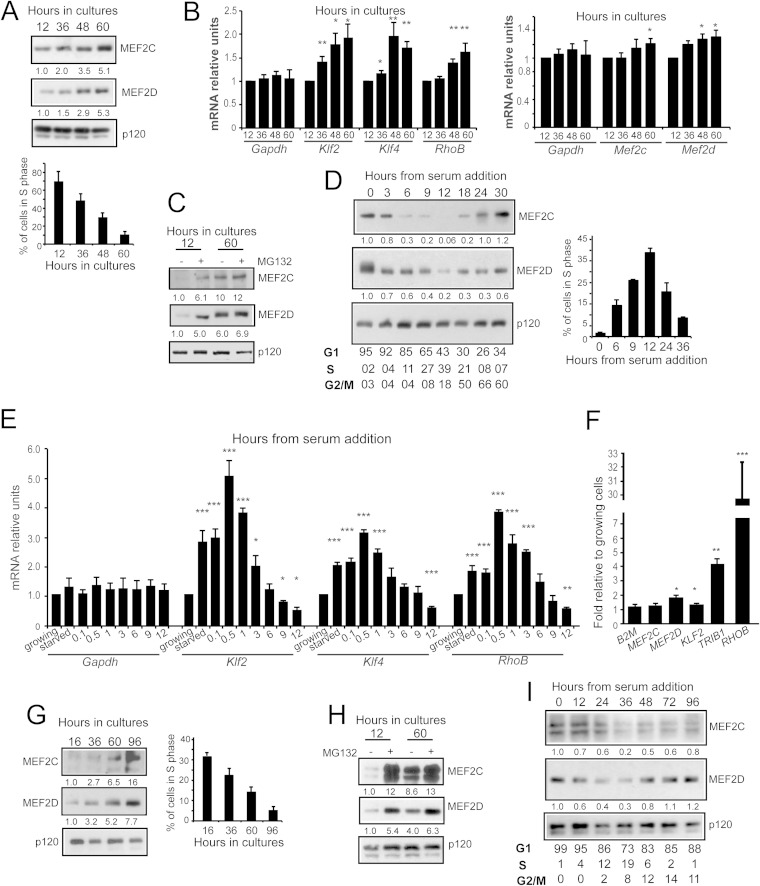

We recently showed that suppression of the PI3K/Akt pathway elicits the upregulation of MEF2C and MEF2D expression (7). This upregulation is mediated by the stabilization of MEF2 proteins, because of a reduced targeting to the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Regulation of MEF2 protein half-life could be a general phenomenon, linked not to PI3K-induced transformation alone but rather to distinct proliferative states of the cells. To explore this hypothesis, we decided to investigate the regulation of MEF2s during different proliferative conditions in untransformed cells. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were selected for these studies, and we initially assessed MEF2 levels during growth arrest, as induced by density-dependent inhibition. Figure 1A illustrates that MEF2C and MEF2D levels increase when cells exit the cell cycle. Densitometric analysis further proved this upregulation. Analysis of BrdU incorporation confirmed entry into the quiescence state following contact inhibition. In parallel, levels of mRNAs of MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB), including Mef2c and Mef2d themselves, rise during density-dependent growth inhibition (Fig. 1B). Experiments using MG132 proved that the UPS plays a key role in the control of MEF2s levels under the different growth conditions. Blocking the proteasome-mediated degradation efficiently augmented MEF2C and MEF2D levels only in growing cells (Fig. 1C). Finally, when G0 serum-deprived cells were restimulated to grow, by addition of 10% FCS, MEF2C and MEF2D levels decreased as cells entered the S phase (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

MEF2C and MEF2D levels are regulated during the cell cycle. (A) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in NIH 3T3 cells grown for the indicated times in 10% FCS. The fraction of cells synthetizing DNA was scored after BrdU staining. p120 was used as a loading control. (B) mRNA expression levels of three MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB), Mef2c, and Mef2d in NIH 3T3 cells grown for the indicated times in 10% FCS. mRNA levels are relative to the first time point (12 h). Gapdh was used as a control gene. Data are means and SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2C and MEF2D levels in NIH 3T3 cells grown for the indicated times in 10% FCS and treated for 10 h with MG132 or not treated, as indicated. p120 was used as a loading control. (D) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2C and MEF2D in NIH 3T3 cells, reintroduced into the growth cycle with 10% FBS, after serum starvation for 48 h. Cellular lysates were collected at the indicated time points. Cytofluorimetric analysis of cell cycle parameters is provided in the lower panel. BrdU positivity is shown in the histogram. (E) mRNA expression levels of three MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB) in NIH 3T3 cells collected 12 h after seeding (growing) or grown for an additional 48 h in 0.5% FBS (starved) and then reintroduced into the growth cycle for the indicated times. mRNA levels are relative to growing condition. Gapdh was used as a control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005. (F) mRNA expression levels of three MEF2 target genes (KLF2, TRIB1, and RHOB), MEF2C, and MEF2D in growing BJ/TERT cells (16 h) compared to density-arrested cells (96 h). mRNA levels are relative to the first time point (16 h). The β2 microglobulin gene was used as a control gene. Data are means and SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005. (G) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in human BJ/TERT cells. Cellular lysates were collected at different times after seeding, as indicated. The fraction of cells synthetizing DNA was scored after BrdU staining. p120 was used as a loading control. (H) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in BJ/TERT cells collected at different times after seeding and treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, as indicated. p120 was used as a loading control. (I) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in BJ/TERT cells, starved for 72 h, reactivated with 10% FBS, and collected at different times after reactivation, as indicated. Cell cycle analysis results are provided in the lower panel.

Previous studies demonstrated that MEF2s are engaged in the transcription of serum-induced immediate early genes (13, 14, 15). Hence, we decided to follow the expression levels of MEF2 target genes after serum stimulation of quiescent cells. The time course analysis (Fig. 1E) confirmed that at early times after serum addition, expression of these genes is augmented. Also, Mef2c and Mef2d mRNAs were upregulated, but at a very modest level (data not shown). However, these upregulations were transient, and 3 h after stimulation for Klf2 and Klf4, or 6 h in the case of RhoB, mRNA levels were reduced compared to those in quiescent cells. These results are in agreement with the described downregulation of MEF2C and MEF2D proteins occurring during late G1/S phase (Fig. 1D). Interestingly after 12 h of stimulation, when cells are mainly in S phase, expression of the MEF2 targets was significantly reduced compared to exponentially growing cells.

To confirm our observations, we also investigated the regulation of MEF2C and MEF2D genes during the cell cycle in human fibroblasts. Immortalized BJ cells expressing TERT gene were arrested in a density-dependent manner. Figure 1F shows that MEF2 target genes, in particular TRIB1 and RHOB, were induced following density-dependent inhibition. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that MEF2C and MEF2D levels increase during growth arrest (Fig. 1G). The strong discrepancy between the changes in RNA and protein levels of MEF2C and MEF2D (compare Fig. 1F and G) further indicates the involvement of the UPS. In fact, as reported for murine fibroblasts, proteasomal inhibition increased MEF2C and MEF2D levels in growing cells, but it had a lower impact on density-arrested cells (Fig. 1H). Also in human fibroblasts, reintroduction of serum-deprived cells into the growth cycle was coupled to an S-phase-mediated MEF2C and MEF2D downregulation (Fig. 1I).

SKP2 regulates MEF2C and MEF2D stability.

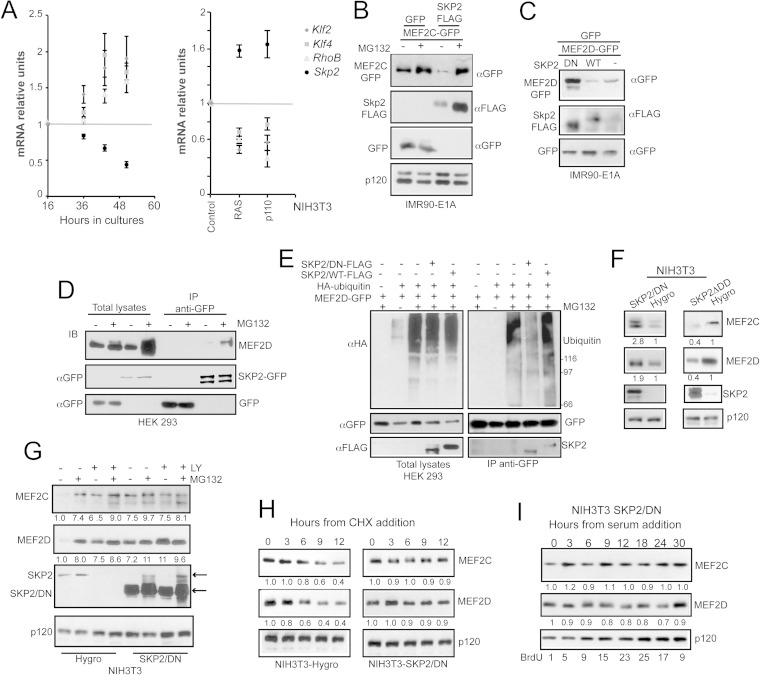

A key point of MEF2C and MEF2D regulation during the cell cycle is their targeting of the UPS. To identify the ubiquitin E3 ligase involved in such a task, we compared gene expression profiles of growing versus quiescent cells, as well as of cells transformed with RAS and PI3K oncogenes versus the normal counterpart. All conditions were marked by a decreased half-life of MEF2 proteins (7) (data not shown). Among the ubiquitin E3 ligases upregulated in both transformed and growing cells, we focused our attention on SKP2 (S-phase kinase-associated protein 2), also known as FBXL1 (19). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that expression levels of Skp2 inversely correlate with the MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB), during density-dependent inhibition and in RAS- or PI3K-transformed murine fibroblasts (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, analysis of publicly available gene expression profiles in different tumors revealed a significant inverse correlation between the expression of MEF2 target genes and SKP2 in soft tissue sarcomas, gastric cancer, metastatic skin carcinoma, metastatic melanoma, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

SKP2 binds and mediates the ubiquitylation of MEF2C/D. (A) mRNA expression levels of MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB) and of Skp2 in NIH 3T3 cells grown for the indicated times in 10% FBS or expressing p110-CAAX and H-RAS. The scheme highlights the inverse correlation between MEF2 target expression levels and Skp2. (B) IMR90-E1A cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1-MEF2C (1 μg) and 2 μg of pFLAG-CMV5a SKP2 or pFLAG-CMV5a GFP as a control. After 24 h, cells were treated with MG132 or left untreated, and after 12 h, cellular lysates were generated and subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. p120 was used as a loading control. (C) IMR90-E1A cells were transfected with pEGFP-C2-MEF2D (1 μg), 2.5 μg of pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2, pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2DN, or empty pFLAG-CMV5a as a control and 200 ng of pEGFP-C2. After 36 h, cellular lysates were generated and subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (D) Cellular lysates from HEK-293 cells, transfected with 5 μg of pEGFP-N1-SKP2 or with empty pEGFP-C2 plasmids and treated for 8 h with 2.5 μM MG132 or left untreated, were immunoprecipitated with an anti-GFP antibody. Immunoblots were performed using the indicated antibodies. (E) HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with the HA-ubiquitin gene (1 μg) and MEF2D-GFP (2 μg) or GFP and SKP2-FLAG or SKP2DN-FLAG or an empty plasmid (4 μg). Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated for 8 h with 2.5 μM MG132 or left untreated. GFP fusions were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against GFP and were subjected to immunoblotting using an antiubiquitin antibody. After being stripped, the filter was probed with anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies. Inputs are included. (F) Immunoblot analysis of MEF2 family members and SKP2 in NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing the dominant negative form (DN) or the hyperactive form (ΔDD) of SKP2 or the control gene (Hygro). Immunoblotting was performed using the indicated antibodies. p120 was used as the loading control. (G) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members and SKP2 in NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing the dominant negative form (DN) of SKP2 or the control gene (Hygro) and treated 12 h after the seeding with LY294002 for 24 h and for the last 12 h with MG132, or left untreated, as indicated. Untreated cells were harvested after 36 h from seeding. p120 was used as the loading control. The lower arrow points to ectopically expressed SKP2/DN. The higher arrow points to a band showing the same size of the endogenous SKP2. (H) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing the dominant negative form of SKP2 (SKP2DN) or the control (HYGRO) and treated for the indicated times with 10 μg/ml of CHX. (I) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members in NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing SKP2DN, starved for 48 h, reactivated with 10% FBS, and collected at different times after stimulation, as indicated. BrdU positivity is shown at the bottom.

To prove the relationships between SKP2 and MEF2s, we performed coexpression studies in human fibroblasts expressing the E1A oncogene. The amount of ectopically expressed MEF2C-GFP (Fig. 2B) was dramatically reduced in the presence of coexpressed SKP2, and proteasomal inhibition recovered its levels. Similarly, MEF2D-GFP levels were downregulated by the simultaneous coexpression of SKP2. Moreover, a deletion-containing version of the E3 ligase acting as dominant negative (ΔF box) (20) efficiently rescued MEF2D-GFP levels (Fig. 2C).

We next investigated whether MEF2D could interact with SKP2. MEF2D was selected for this analysis because of its higher expression, compared to MEF2C, in fibroblasts (21). After coimmunoprecipitation, a complex between endogenous MEF2D and SKP2 was purified from cells expressing SKP2-GFP, and the amount of MEF2D bound to SKP2 was dramatically increased following MG132 treatment (Fig. 2D). MEF2D-GFP expressed in 293 cells was polyubiquitylated, and coexpression with SKP2 increased this polyubiquitylation, whereas SKP2DN reduced it (Fig. 2E). When the dominant negative version of SKP2 was stably expressed in NIH 3T3 cells, levels of MEF2C and MEF2D proteins increased. In contrast, introduction of a hyperactive version of SKP2, SKP2ΔDD (22), caused a dramatic reduction of both MEF2C and MEF2D levels (Fig. 2F).

When NIH 3T3 cells are challenged with MG132 or with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY), MEF2C and MEF2D abundance increases (7). In cells expressing SKP2/DN, the levels of the two MEF2s were higher than control levels. Treatment with LY, MG132, or both failed to further increase the quantities of these TFs (Fig. 2G). This result indicates that SKP2 is the crucial E3 ligase engaged by the PI3K pathway to switch off MEF2 activities. To further prove the contribution of SKP2, we also used cycloheximide (CHX). In proliferating cells, a block of protein synthesis elicited a reduction of MEF2C and MEF2D, already appreciable at 6 h from CHX addition. This reduction was abolished in cells expressing SKP2/DN (Fig. 2H). Finally, the downregulation of MEF2C and MEF2D observed in serum-deprived cells stimulated with 10% FCS was also abrogated in SKP2/DN-expressing cells (compare Fig. 2I and 1D). Not surprisingly, these cells exhibited a reduced ability to enter S phase after serum stimulation. In summary, these results indicate that SKP2 is a critical E3 ligase dictating MEF2C and MEF2D protein levels during the cell cycle.

Molecular determinants of the MEF2-SKP2 interaction.

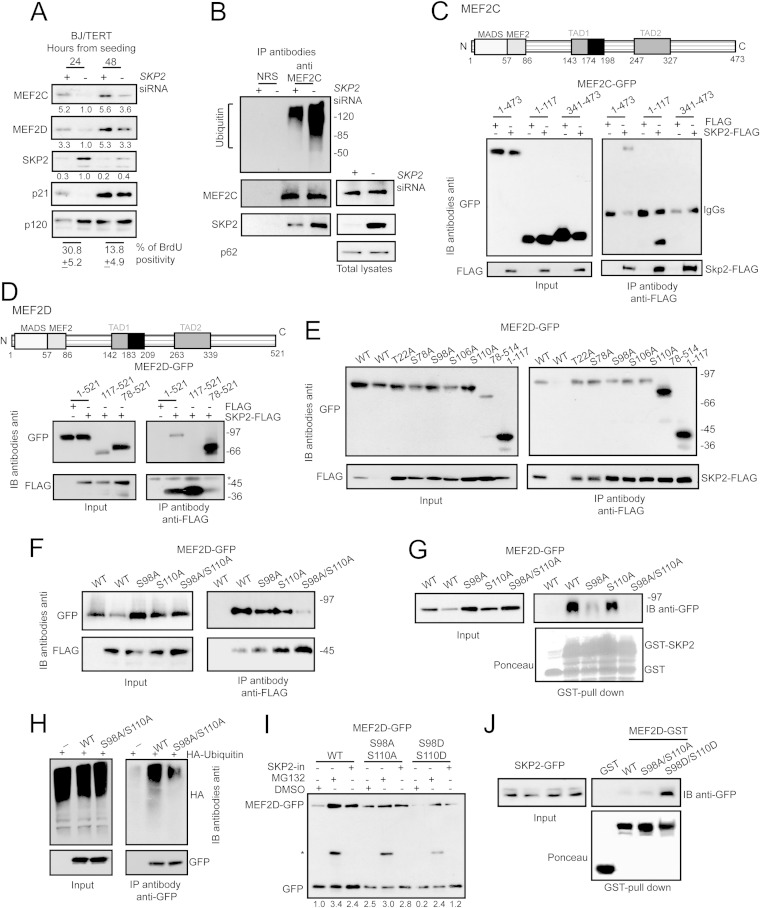

To further confirm the influence of SKP2 on MEF2 stability, we silenced its expression in human fibroblasts. Downregulation of SKP2 provoked the upregulation of both MEF2C and MEF2D proteins (Fig. 3A). The CDK inhibitor p21, a SKP2 substrate, was used as a positive control (23). Furthermore, we also proved that polyubiquitylation of MEF2C was reduced in SKP2-silenced cells (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Mapping of SKP2 binding to MEF2C/D and characterization of SKP2 interference. (A) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2 family members SKP2 and p21 in BJ/TERT cells transfected for 36 h with SKP2 siRNA. Transfections were performed 24 h or 48 h after seeding, as indicated. p120 was used as the loading control. BrdU positivity is shown at the bottom. (B) BJ/TERT cells were transfected with SKP2 siRNA. After 24 h cells were treated for 8 h with 2.5 μM MG132 or left untreated. MEF2C complexes were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against MEF2C and were subjected to immunoblotting using an antiubiquitin antibody. After being stripped, the filter was probed with an anti-MEF2C antibody and an anti-SKP2 antibody. Inputs and p62 (nucleoporin), as the loading control are included. (C) Scheme of MEF2C domains. The MADS and MEF2 domains and the two transcriptional activation domains (TADs) are indicated. HEK-293 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1-MEF2C deletions (1.5 μg) and pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2 or pFLAG-CMV5a (4 μg) and treated for 8 h with 2.5 μM MG132. FLAG fusions were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against FLAG and were subjected to immunoblotting using an anti-GFP antibody. After being stripped, the filter was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody. Inputs are included. (D) Scheme of MEF2D domains. The MADS and MEF2 domains and the two TADs are indicated. HEK-293 cells were transfected with pEGFP-C2-MEF2D deletion mutants (1.5 μg) and pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2 or pFLAG-CMV5a (4 μg). Experimental treatments and immunoprecipitations were performed as for panel C. The asterisk marks the IgGs. (E) HEK-293 cells were transfected with pEGFP-C2-MEF2D deletion mutants and phosphodead mutants (1.5 μg) and pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2 or pFLAG-CMV5a (4 μg). Experimental treatments and immunoprecipitations were performed as for panel C. (F) HEK-293 cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) pEGFP-C2-MEF2D and single or double phosphodead mutants (1.5 μg) and pFLAG-CMV5a-SKP2 or pFLAG-CMV5a (4 μg). Experimental treatments and immunoprecipitations were performed as for panel C. (G) GST pulldown assay. Cellular lysates from HEK-293 cells expressing WT or phosphodead mutant forms of MEF2D-GFP were incubated with 3 μg of recombinant GST-SKP2 or GST alone. (H) HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with the HA-ubiquitin gene (2 μg) and WT MEF2D-GFP or the double-phospho-mutant (4 μg) or GFP alone and treated for 8 h with 2.5 μM MG132 or left untreated. GFP fusions were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against GFP and were subjected to immunoblotting using an antiubiquitin antibody. After stripping, filter was probed with an anti-GFP antibody. Inputs are included. (I) Immunoblot analysis of MEF2D in IMR90-E1A cells transfected with the wild-type, the phosphomutant, and the phosphomimicking forms of MEF2D fused to GFP (2 μg) and with empty pEGFP-C2 (1 μg), used as the loading control. After 12 h cells were harvested, split in three, and treated for 12 h with DMSO, MG132, and the SKP2 inhibitor (SKP2-in), as indicated. (J) GST pulldown assay. Cellular lysates from HEK-293 cells expressing SKP2-GFP were incubated with 2 μg of GST, GST-MEF2D, or its phosphodead and phosphomimetic mutants, as indicated.

SKP2 interacts with its substrates in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (19). In order to map the amino acid residues critical for this interaction, we initially performed a simple deletion analysis to circumscribe the region involved. In Fig. 3C and D, schematic representations of MEF2C and MEF2D TFs highlighting their principal domains are shown. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments proved that the region from positions 1 to 117 of MEF2C is sufficient for the interaction with SKP2 (Fig. 3C). In accordance, the carboxy terminus of MEF2D is dispensable for this interaction (Fig. 3D). Having identified in the MEF2 amino-terminal portion the region recognized by SKP2, we next applied in silico analysis to locate putative phosphorylation motifs. Again, as explained above, we focused the studies on MEF2D. T22, S78, S98, S106, and S110 of MEF2D (all conserved in MEF2C) resulted in the highest score as putative consensus phosphoacceptor sites.

Single phosphodead substitutions of MEF2D were generated, and the binding to SKP2 was tested after cotransfection of the relative cDNAs in 293 cells. Neither the Ala/Ser nor the Ala/Thr substitution in MEF2D abrogated the binding to SKP2. However, a slightly reduced interaction was observed when serine 98 and 110 were replaced with alanine (Fig. 3E). We next generated MEF2D with double dephosphomimetic substitutions. Simultaneous mutations of Ser 98 and 110 to Ala dramatically reduced the binding of MEF2D to SKP2 in 293 cells (Fig. 3F). Then, we used a GST pulldown assay to confirm the importance of Ser 98 and 110 for the interaction with SKP2. In the pulldown assay, the single substitution S98A diminished the binding to SKP2, whereas the double mutation S98A/S110A completely abrogated it (Fig. 3G). We also proved that polyubiquitylation of the S98A/S110A double mutant was largely compromised but not totally suppressed compared to that of the wild-type (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, MG132 and the SKP2 inhibitor increased the amounts of MEF2D-GFP and of the phosphomimetic double mutant (S98D/S110D) but not that of the S98A/S110A double mutant (Fig. 3I). Finally, the GST pulldown assay established that the interaction between SKP2 and the recombinant MEF2D was dramatically improved in the case of the phosphomimetic double mutant (Fig. 3J). These results indicate that phosphorylation of serines 98 and 110 plays an important role in the control of MEF2D stability, by mediating the interaction with SKP2.

MEF2D is a substrate of CDK4.

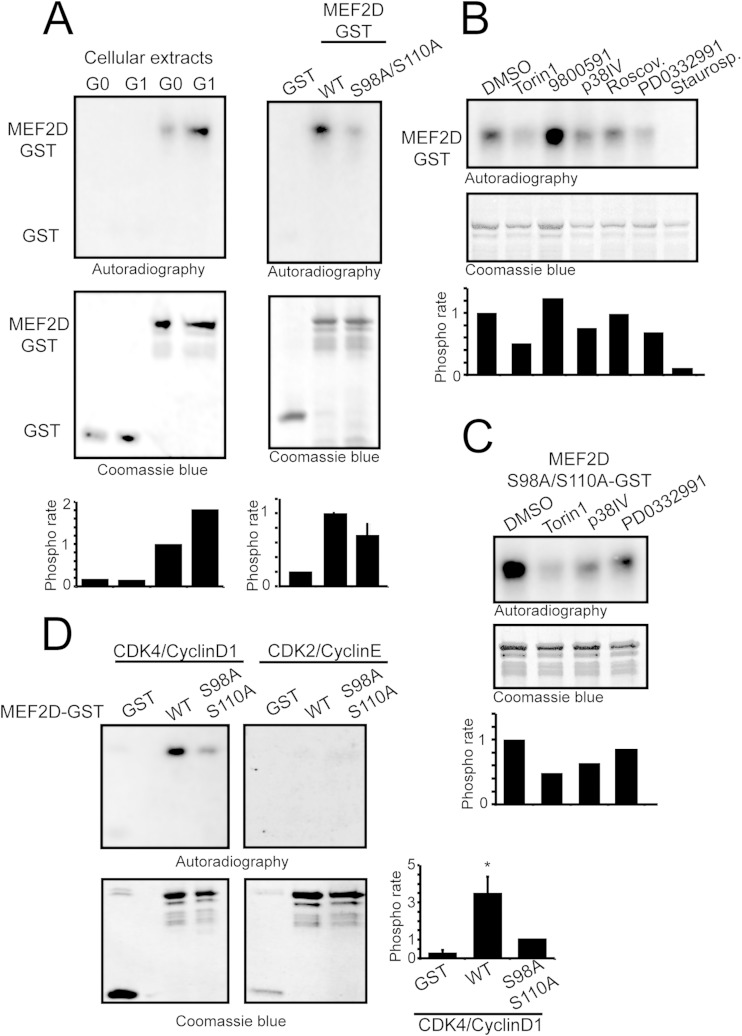

To identify the kinases responsible for MEF2D phosphorylation on serines 98 and 110, we initially arranged an in vitro phosphorylation assay using crude cellular extracts from NIH 3T3 cells as a source of kinase activities. When a MEF2D-GST fusion protein comprising amino acids 1 to 190 was incubated with these cellular extracts in the presence of radiolabeled γ-ATP, it was phosphorylated (Fig. 4A). MEF2D-GST phosphorylation was augmented when extracts were obtained from cells in the G1 phase compared to quiescent G0 cells. Coomassie blue gel staining verified the amount of recombinant protein loaded. Under the same experimental conditions, GST alone was not phosphorylated. When the MEF2D-S98A/S110A double mutant was used, phosphorylation was reduced but not abrogated, thus indicating that the two serine residues are targets of some kinase and that additional amino acids can be phosphorylated in vitro (Fig. 4A). Since S98 and S110 share consensus phosphorylation sequences for several kinases (ERKs, mTOR, p38, CDK2, and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 [CDK4]), we tested whether the relative specific inhibitors could influence MEF2D phosphorylation in our in vitro phosphorylation assay. Staurosporine was used as a positive control. Only mTOR, p38, and CDK4 inhibitors reduced MEF2D(1–190) phosphorylation, thus confirming the existence of multiple MEF2 kinases in the cellular extracts (Fig. 4B). Next, we used the MEF2D-S98A/S110A double mutant, in order to understand which kinase could be involved in the phosphorylation of these residues. The p38 and mTOR inhibitors effectively repressed phosphorylation of the double mutant, whereas the CDK4 inhibitor was the less efficient (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that CDK4 is the kinase that could be more specifically involved in the phosphorylation of S98 and S110, whereas mTOR and p38 are principally implicated in phosphorylating other residues. Finally, to verify the contribution of CDK4, the complex CDK4/cyclin D1 was tested for the ability to phosphorylate MEF2D-GST. To evaluate the specificity, the related kinase CDK2/cyclin E was used for comparison. Only CDK4/cyclin D1 was able to phosphorylate MEF2D in vitro and this phosphorylation was reduced but not abrogated when the S98A/S110A mutant was used (Fig. 4D), thus pointing to the existence of additional phosphorylation sites. The efficacy of both kinases was tested on GST-Rb (data not shown). In conclusion, the 1–190 fragment of MEF2D is the target of multiple kinases in different residues, and CDK4/cyclin D1 can phosphorylate MEF2D on serines 98 and 110, as well as on additional residues.

FIG 4.

MEF2D is phosphorylated by CDK4. (A) (Left) Autoradiography after in vitro phosphorylation of MEF2D-GST and GST as a control, using cellular extracts from serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells, incubated for 4 h with 10% FCS or left untreated. (Right) Autoradiography after in vitro phosphorylation of WT and phosphodead MEF2D-GST and GST alone using cellular extracts from NIH 3T3 cells that had been serum starved and treated for 4 h with 10% FCS. Coomassie staining was used as the loading control. Densitometric analysis is also shown. (B and C) Autoradiography after in vitro phosphorylation performed on GST-MEF2D (B) and the phosphodead mutant (C) in the presence of the indicated kinase inhibitors or DMSO. Crude cellular extracts were obtained from NIH 3T3 cells that had been serum starved and then treated for 4 h with 10% FCS. Coomassie staining was used as the loading control. Densitometric analysis is also provided. (D) Autoradiography after in vitro phosphorylation performed on GST-MEF2D and GST-MEF2D S98A/S110A, using recombinant cyclin D1/CDK4 or cyclin E1/CDK2. Coomassie staining was used as the loading control. Densitometric analysis is also provided. *, P < 0.05.

Roles of MEF2s in the regulation of cell cycle progression.

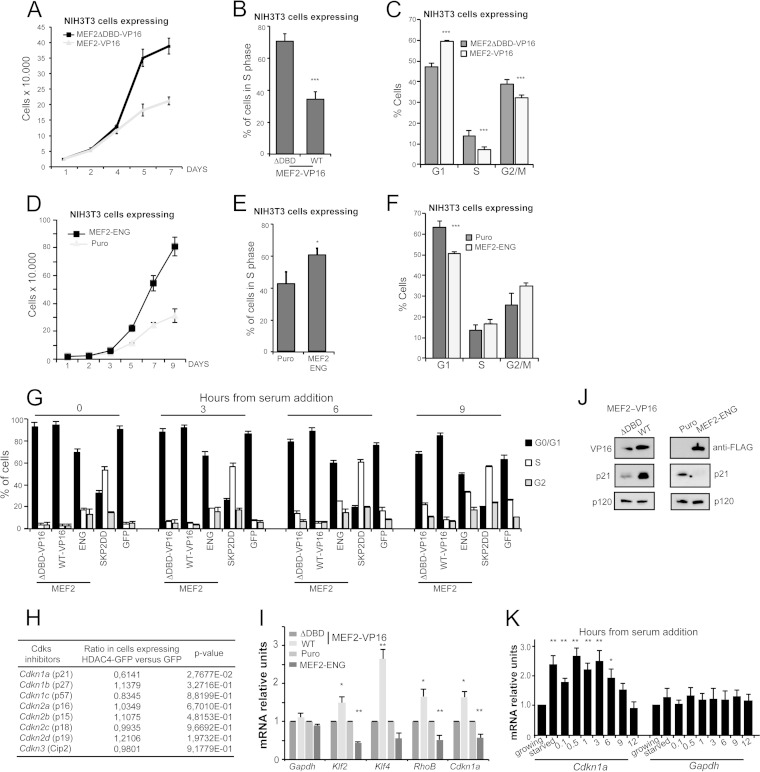

The discovery of the tight regulation of MEF2s stability during cell cycle progression prompted us to explore the effect of artificially altering MEF2 transcriptional activity on cell proliferation. We used the MEF2-VP16-ER chimera and, as a control, the MEF2-VP16-ER construct lacking the DNA-binding domain (ΔDBD, amino acids 58 to 86). NIH 3T3 cells expressing transcription-competent MEF2 are characterized by a reduced proliferative profile, as indicated by the reduction in cell numbers (Fig. 5A), the diminished percentage of cells incorporating BrdU (Fig. 5B), and the increased number of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 5C). To strengthen this observation, we used a repressive version of MEF2 (24), generated by fusing the MADS/MEF2 domains to the transcriptional repressor Engrailed (MEF2-ENG). Cells expressing the repressive version of MEF2 increased their proliferation rate, as evidenced by (i) the increased number of cells (Fig. 5D), (ii) the highest percentage of BrdU incorporation (Fig. 5E), and (iii) the reduced number of cells in G1 (Fig. 5F).

FIG 5.

MEF2s affect NIH 3T3 fibroblasts proliferation by inducing CDKN1A expression. (A) NIH 3T3 cells expressing the two transgenes and treated with 4-OHT were grown for the indicated times. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (B) Forty-eight hours after seeding, quantification of BrdU positivity of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes and treated with 4-OHT was performed. Data are means and SD (n = 5). (C) Cell cycle profile of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes and treated with 4-OHT. Analysis was performed 48 h after seeding. Data are means and SD (n = 4). (D) NIH 3T3 cells expressing the two transgenes were grown for the indicated times. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (E) Forty-eight hours after seeding, quantification of BrdU positivity of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes was performed. Data are means and SD (n = 5). (F) Cell cycle profile of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes. Analysis was performed 48 h after seeding. Data are means and SD (n = 4). (G) Cell cycle profile of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes, serum starved (time zero) or at different times after serum addition. SKP2DD was used as a positive control for unrestricted proliferation. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (H) mRNA induction (n-fold) of the indicated CDK inhibitors, obtained by comparing their levels of expression in NIH 3T3 cells expressing HDAC4-GFP and those expressing GFP as a control (7). (I) mRNA expression levels of MEF2 target genes (Klf2, Klf4, and RhoB) and Cdkn1a in NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes and collected 36 h after the seeding. Gapdh was used as a control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (J) Immunoblot analysis of p21/CDKN1A levels in NIH 3T3 cells expressing the indicated transgenes. Anti-VP16 and anti-FLAG antibodies were used to reveal the expression of the transgenes. p120 was used as the loading control. (K) mRNA expression levels of Cdkn1a in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells stimulated with 10% FCS as indicated. Gapdh was used as a control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

We next investigated the behavior of NIH 3T3 cells expressing the different MEF2 versions during the G0/G1 transition following readdition of serum to starved cells. In this study, we also compared the behavior of cells expressing SKP2ΔDD, a hyperactive version of the E3 ligase (Fig. 5G). As expected, the cell cycle profile of cells expressing the hyperactive SKP2 exhibited a high percentage of cells in S phase also under starvation, thus indicating their inability to enter G0. In serum-starved cells expressing the repressive version of MEF2, cycling cells can still be detected (approximately 30% of the cells in S and G2 phases). Readdition of serum elicited cell cycle reentry in GFP and ΔDBD cells, whereas in the presence of the transcriptionally active MEF2, the percentage of cells approaching S phase was diminished (Fig. 5G).

CDK inhibitors are key regulators of cell cycle progression (25). To evaluate a possible contribution of these inhibitors in transducing MEF2 antiproliferative signal, we took advantage of the profile of genes repressed in NIH 3T3 cells, after expression of a nuclear resident form of HDAC4, since the vast majority of these genes are MEF2 targets (7). Figure 5H shows that Cdkn1a was the sole CDK inhibitor significantly repressed by HDAC4. We next compared the expression patterns of some MEF2 targets and of Cdkn1a in the cell lines engineered to express the different MEF2 variants. Cdkn1a shows a pattern of expression similar to that of other MEF2 target genes, being increased in MEF2-VP16 and reduced in MEF2-ENG cell lines (Fig. 5I). The influence of the two MEF2 chimeras on p21 was confirmed also at protein levels (Fig. 5J). We also analyzed the pattern of p21 expression following serum stimulation of starved cells. Similar to the other MEF2 targets, Cdkn1a mRNA levels were upregulated at starvation and slowly declined during the G1/S transition (9/12 h from stimulation). Compared to the other MEF2 targets analyzed, Cdkn1a was induced to a much lesser extent at early times from serum stimulation (Fig. 5K).

Having defined a mechanism through which MEF2s could suppress cell proliferation, we wanted to confirm the growth inhibitory activity of MEF2 in human cells. We used BJ/TERT human fibroblasts expressing a mutated p53 allele, acting as dominant negative, and cells not expressing this allele. Since CDKN1A is an important p53 target gene, we wanted to exclude an involvement of this tumor suppressor in the antiproliferative activity elicited by MEF2s. Induction of MEF2-dependent transcription using the MEF2-VP16-ER chimera dramatically suppressed cell proliferation and DNA synthesis in a p53-independent manner (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). Upregulation of MEF2 target genes and of CDKN1A was confirmed following MEF2 transcriptional activation in both BJ/TERT and BJ/TERT/p53DN cells (see Fig. S2C and D in the supplemental material). Upregulation of CDKN1A was also verified by immunoblotting (see Fig. S2E in the supplemental material). Both analyses showed that MEF2-dependent upregulation of CDKN1A is p53 independent.

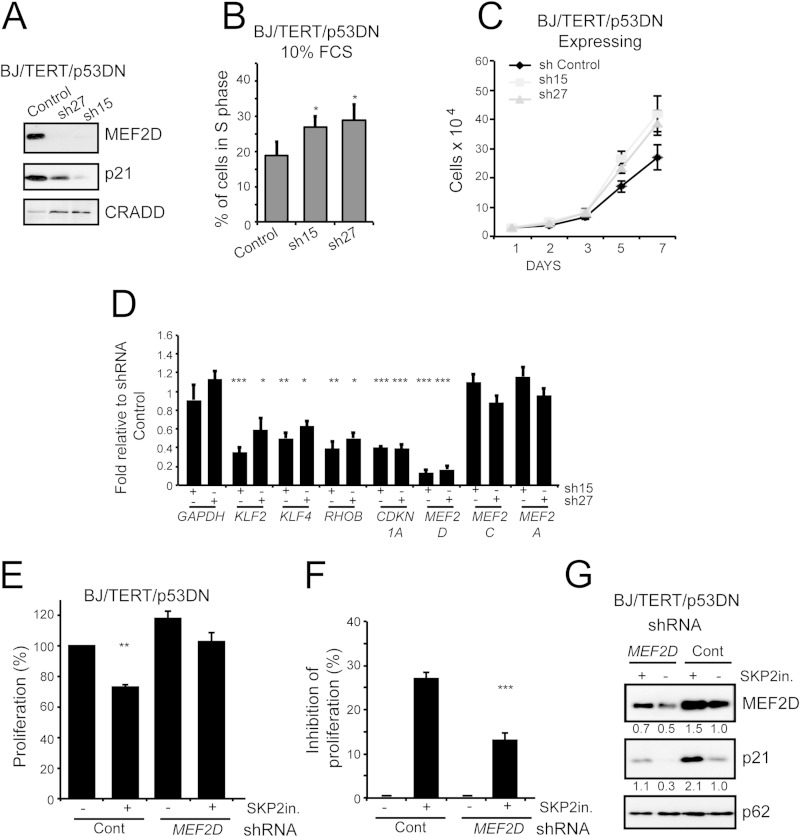

To unambiguously demonstrate the role of MEF2s in the control of cell cycle, we downregulated MEF2D expression following lentiviral infection. Two different shRNAs were evaluated (sh15 and sh27). In BJ/TERT/p53DN cells, MEF2D downregulation was coupled with the reduction of CDKN1A levels (Fig. 6A), an increase in DNA synthesis (Fig. 6B) and augmented cell proliferation (Fig. 6C). mRNA levels of MEF2 target genes and of CDKN1A were reduced in cells with impaired MEF2D expression (Fig. 6D). The specificity of the shRNAs against MEF2D with respect to other MEF2 members was also demonstrated (Fig. 6D).

FIG 6.

MEF2s affect proliferation of human fibroblasts by inducing CDKN1A expression. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p21/CDKN1A in BJ/TERT/p53DN cells silenced for MEF2D expression using two different shRNAs (sh15 and sh27). The efficiency of the downregulation was proved with an anti-MEF2D antibody. CRADD was used as the loading control. (B) Quantification of BrdU positivity of BJ/TERT/p53DN silenced (sh15 and sh27) for MEF2D or not silenced (shCT). Analyses were performed 48 h after seeding. Data are means and SD (n = 4). (C) BJ/TERT/p53DN cells expressing the indicated shRNAs were grown for the indicated times. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (D) mRNA expression levels of MEF2 target genes (KLF2, KLF4, and RHOB) and of CDKN1A in BJ/TERT/p53DN cells in which MEF2D expression was downregulated using two different shRNAs, as indicated. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (E) Quantification of the proliferation rate of BJ/TERT/p53DN cells silenced for MEF2D or not silenced and treated for 24 h with the SKP2 inhibitor or left untreated, as indicated. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (F) Proliferation inhibition in BJ/TERT/p53DN cells knocked down for MEF2D or not knocked down and treated with SKP2 inhibitor or left untreated, as indicated. Data are relative to those for untreated cells and presented as means and SD (n = 3). (G) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of MEF2D and p21/CDKN1A levels in BJ/TERT/p53DN cells treated as for panel E. p62 (nucleoporin) was used as the loading control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

We again decided to verify the proproliferative effect of MEF2D downregulation in a different cell line. When BJ/TERT/E1A/RAS cells were used, the results were confirmed. Downregulation of MEF2D expression was coupled to (i) a downregulation of CDKN1A/p21 levels (see Fig. S2F in the supplemental material), (ii) an improvement of the percentage of cells in S phase (see Fig. S2G in the supplemental material), and (iii) an overall increase of cell proliferation (see Fig. S2H in the supplemental material). Finally, the tested MEF2 target genes were all downregulated (see Fig. S2I in the supplemental material).

Small molecules targeting SKP2 show interesting anticancer properties (26). We tested a SKP2 inhibitor for the ability to restrain proliferation of BJ/TERT/p53DN cells, and we also analyzed the contribution of MEF2D for transducing such antiproliferative response. Figure 6E illustrates that the SKP2 inhibitor can diminish the proliferation of BJ/TERT/p53DN cells. More importantly, the antiproliferative effect of the SKP2 inhibitor (Fig. 6F) and the upregulation of p21 (Fig. 6G) were consistently reduced in the absence of MEF2D. These results further confirm a key role of MEF2 in transducing antiproliferative signals, possibly through the engagement of p21.

CDKN1A is a key element in the antiproliferative activity of MEF2.

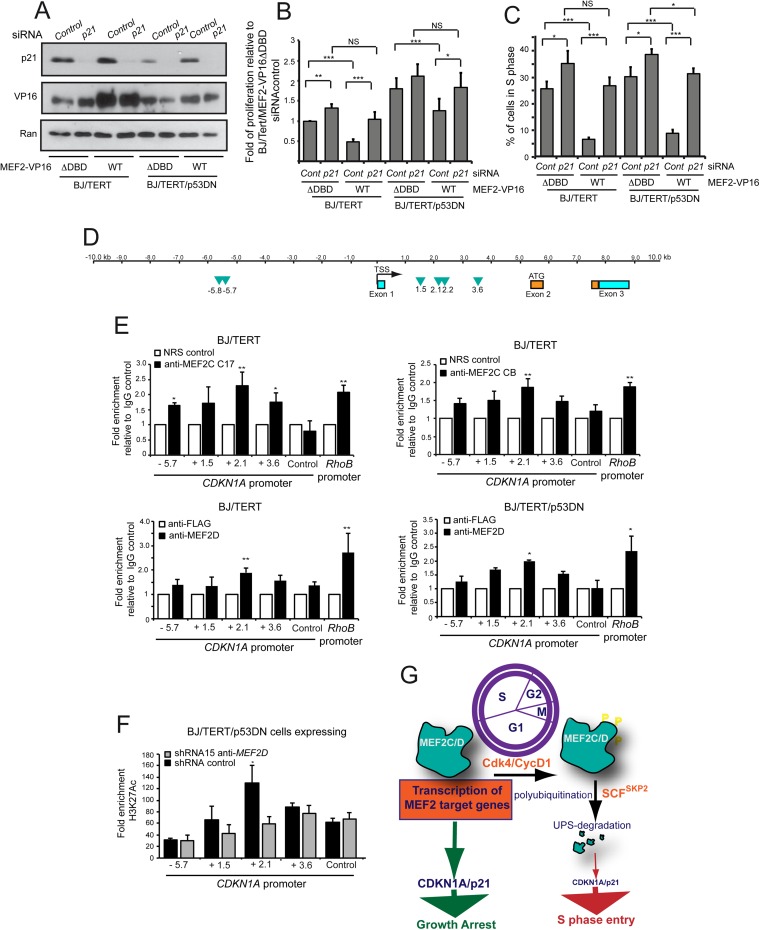

To elucidate the contribution of CDKN1A to the antiproliferative signaling of MEF2s, we silenced its expression in BJ/TERT and BJ/TERT/p53DN cells expressing the inducible MEF2 or its mutant with a deletion in the DNA binding domain (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

MEF2D antiproliferative effects rely mainly on its direct regulation of CDKN1A transcription. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p21/CDKN1A in BJ/TERT and BJ/TERT/p53DN cells expressing the indicated transgenes, treated with 4-OHT, and silenced for the p21/CDKN1A gene or not silenced, as indicated. Anti-VP16 and anti-Ran antibodies were used, respectively, to reveal the expression of the transgenes and as the loading control. (B) Quantification of the proliferation rate of the indicated cell lines relative to BJ/TERT/MEF2ΔDBD cells treated for 36 h with siRNA against the p21/CDKN1A gene or the siRNA control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (C) Quantification of BrdU positivity of the indicated cell lines, treated as for panel B. Data are means and SD (n = 4). (D) Representation of the CDKN1A gene structure and its promoter region 10 kb upstream and downstream from the transcription start site (TSS). The putative MEF2 binding sites are highlighted (green). The coding (orange) and the noncoding (light blue) exons and the ATG leader are also indicated. (E) ChIP of BJ/TERT and BJ/TERT/p53DN cells. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using two distinct antibodies against MEF2C and one against MEF2D. Normal rabbit serum (NRS) and anti-Flag antibody were used as relative controls. The RHOB promoter was used as a positive control, and an internal region (kb +4.7 from the TSS) of the CDKN1A gene was used as a negative control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (F) ChIP of BJ/TERT/p53DN cells in which MEF2D was knocked down with shRNA 15. The H3K27 acetylation status of the putative MEF2 binding sites on CDKN1A promoter is shown. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against acetylated H3K27 (H3K27ac), and normal rabbit serum (NRS) was used as a relative control. Data are means and SD (n = 3). (G) Model representing the cell cycle-mediated regulation of MEF2 levels and MEF2 feedback activity on cell cycle progression. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

When CDKN1A was downregulated, the antiproliferative effect and the inhibition of DNA synthesis elicited by MEF2 upregulation were almost entirely abrogated (Fig. 7B and C).

Changes in CDKN1A levels following MEF2 perturbations could reflect either a direct involvement of MEF2s in regulating its transcription or an indirect role, through the regulation of other TFs, such as KLF4 (27) and KLF2 (28). To clarify these possibilities, we scrutinized the genomic region around the CDKN1A transcription start site for the presence of MEF2-binding consensus sequences. Figure 7D schematizes the organization of the CDKN1A genomic region and highlights the presence of 6 putative MEF2-binding sequences in the promoter and in the first intron of CDKN1A gene. ChIP experiments using two different anti-MEF2C antibodies indicate that MEF2C can interact with the CDKN1A genomic region, and the highest enrichment was obtained for the MEF2 consensus sequence at kb +2.1 from the transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 7E). This enrichment was comparable to the positive control, the region containing the MEF2-binding sequence of the RhoB promoter. Similar results were observed when the ChIP experiments were performed using an antibody against MEF2D. We verified that MEF2D also binds the same genomic region in cells expressing mutated p53 (Fig. 7E).

The genomic region of CDKN1A bound by MEF2 was previously characterized by the ENCODE project as enriched in histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1) (29), two markers of active enhancers (30). These data suggest that MEF2 might actively regulate p21 transcription by binding to an active enhancer and could itself recruit other cofactors, such as the acetyltransferase p300 (31), which in turn cooperate to maintain the open chromatin state. To confirm this hypothesis, we performed ChIP experiment using anti-H3K27Ac antibody. Figure 7F illustrates that the highest enrichment for H3K27 acetylation can be observed around kb +2.1 from the TSS in the same region where MEF2C and MEF2D binding was observed. Furthermore, in cells with downregulated MEF2D, the acetylation of H3K27 was clearly reduced specifically at kb +2.1 from the TSS.

DISCUSSION

MEF2s are pleiotropic TFs, which influence different genetic programs in relation to specific posttranslational modifications (PTMs) and the associations with other transcription factors, coactivators, or repressors (1). The contribution of MEF2s to several differentiation processes is well known. MEF2s supervise differentiation of myoblasts (32), cardiomyoblasts (33), osteoblasts (24), neuronal cells (10, 34), B lymphocytes, and monocytes (35). Mice with Mef2 genes knocked out display phenotypes compatible with defects in these differentiative programs at an advanced stage, suggesting that MEF2s regulate the final steps of these processes (1, 24, 33, 35). Furthermore, in a wide variety of differentiated cells, MEF2s are also engaged to modulate adaptive responses (1, 36, 37).

In this work, we investigated the still-obscure role of MEF2s in the regulation of the cell cycle. Using human and murine fibroblasts as cellular models, we have demonstrated the reciprocal influence of the cell cycle machinery on MEF2 activities and of MEF2s on cell cycle progression. We have discovered that, in addition to previously documented engagements of MEF2s in governing the early transcriptional response to serum (immediate early genes) (13, 14, 15), MEF2 transcriptional activity is regulated at supplementary steps during the cell cycle.

By simultaneously monitoring the mRNAs of the MEF2 target genes and the levels of MEF2C and MEF2D proteins, we noticed the following. (i) During growth arrest (G0), mRNA upregulation of three MEF2 target genes (KLF2, KLF4, and RHOB) is tightly coupled to the stabilization of MEF2C and MEF2D proteins. (ii) Following growth factor stimulation of serum-starved cells (G0/G1 transition), the expression of MEF2 target genes is rapidly and transiently upregulated. This rapid induction of the MEF2 target genes may depend on specific PTMs induced by serum, potentiating MEF2 activity (18, 38). (iii) As cells progress toward the G1/S phases, MEF2 protein levels drop. Again, the mRNA levels of KLF2, KLF4, and RHOB decrease in parallel. The UPS is responsible for this timing-regulated degradation of MEF2C and MEF2D. Overall, the influence of the cell cycle on the half-lives of MEF2C and MEF2D justifies their accumulation under nonproliferative/quiescent conditions.

Phosphorylation plays a key role for targeting MEF2C and MEF2D to the UPS. We provide evidence that phosphorylation of serine residues 98 and 110 is fundamental for mediating the interaction with the F-box protein SKP2 and the subsequent polyubiquitylation-mediated degradation of the TFs. Since residual MEF2 polyubiquitylation was also observed in the presence of the double phosphodead mutant (S98A/S110A) (Fig. 4I), it is possible that additional Ser/Thr residues or different E3 ligases influence MEF2 stability during the cell cycle. Interestingly, a contribution of the same serine residues to the regulation of MEF2C stability was previously proposed (39).

SKP2 is a positive regulator of cell cycle progression and an oncogenic protein that targets tumor suppressor proteins for degradation (19). Hence, MEF2s polyubiquitylation lies at the core of the machinery controlling cell cycle progression: the SCFSKP2 (SKP1–CUL1–F-box protein) superenzyme. In vitro phosphorylation assays using specific inhibitors and recombinant enzymes suggest that cyclin D1-CDK4 but not cyclin E-CDK2 can phosphorylate serines 98 and 110 of MEF2D. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein RB1 and its family members are key substrates of CDK4/CDK6 D-type cyclins complexes for promoting G1-S transition (40). Interestingly, a catalogue of new substrates of these kinases has been generated. Although more precise information about amino acid involvement is not available, in accordance with our discovery, MEF2D was listed in the catalogue as a CDK4/CDK6 substrate (41).

When we experimentally affected MEF2 levels and activities, the overt evoked phenotype was a reduction of cell proliferation. The importance of the growth-suppressive activity of MEF2s stems also from the diminished antiproliferative impact of the SKP2 inhibitor, when MEF2D expression was downregulated by specific shRNAs.

We have discovered that an important element of the antiproliferative pathway engaged by MEF2s is CDKN1A (Fig. 7G). In agreement with our observations, a recent study demonstrated that ectopically expressed MEF2D can upregulate p21 expression (42). CDKN1A transcription fluctuates during the cell cycle, accumulating in G0 and showing a peak after serum stimulation (43). In human fibroblasts, this pattern is strictly dependent on the presence of MEF2D (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). We have shown that MEF2C and MEF2D bind a genomic region within the first intron, at kb +2.1 from the TSS of the CDKN1A gene, a region characterized by an open chromatin status (29). We have also provided evidence that MEF2D is important for favoring H3K27 acetylation, a well-known marker of active/open chromatin, within the CDKN1A gene, in proximity to its binding site. This epigenetic modification may be governed through the engagement of p300/CBP (31), a well-known MEF2 partner (44, 45, 46).

MEF2D is critical for the upregulation of the immediate early genes response to serum. However, at least in BJ/hTERT/p53DN cells, a reduction of MEF2D activity and the consequent upregulation of MEF2 target genes during G0/G1 transition did not affect entry into S phase (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Certainly, we cannot exclude the possibility that in other cellular contexts, this early activation makes an important contribution to cell cycle progression.

A double role of MEF2 during different phases of the cell cycle could explain the apparent conflicting results about MEF2s' antiproliferative and proproliferative activities found in the literature (14, 15, 47). In particular, MEF2C has been reported to be required for B cell proliferation and survival after BCR stimulation but not after Toll-like receptor stimulation (12); in contrast, MEF2A decreases the proliferation and the migration rates of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (48).

A tight and ordered control of the progression through the cell cycle ensures a harmonic regulation of cell proliferation. Progression through the different phases of the cell cycle is orchestrated by the activity of different TFs, which operate under the influence of the cell cycle machinery and allow the ordered (hierarchical) transcription of cell cycle-regulated genes (49). Our studies add MEF2s to the list of the transcriptional regulators, which are an integral part of the machinery that controls the cell cycle.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by AIRC (IG-10437) and MIUR Progetto PRIN (Progetto 2010W4J4RM_002) grants to C.B.

We thank Michele Pagano (New York University) for the SKP2DN plasmid, Mauro Giacca (ICGEB, Trieste, Italy) for the Rb plasmid, Eric Olson (Dallas, TX) for the plasmid encoding MEF2-ENG, and Kevin Ryan (Glasgow, United Kingdom) and Peiqing Sun (La Jolla, CA) for E1A plasmids.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01461-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. 2007. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development 134:4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu YT. 1996. Distinct domains of myocyte enhancer binding factor-2A determining nuclear localization and cell type-specific transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 271:24675–24683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wales S, Hashemi S, Blais AMJ. 2014. Global MEF2 target gene analysis in cardiac and skeletal muscle reveals novel regulation of DUSP6 by p38MAPK-MEF2 signaling. Nucleic Acids Res 42:11349–11362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandmann T, Jensen LJ, Jakobsen JS, Karzynski MM, Eichenlaub MP, Bork P, Furlong EEM. 2006. A temporal map of transcription factor activity: Mef2 directly regulates target genes at all stages of muscle development. Dev Cell 10:797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalizi A, Gaudillière B, Yuan Z, Stegmüller J, Shirogane T, Ge Q, Tan Y, Schulman B, Harper JW, Bonni A. 2006. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science 311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clocchiatti A, Di Giorgio E, Ingrao S, Meyer-Almes F-J, Tripodo C, Brancolini C. 2013. Class IIa HDACs repressive activities on MEF2-depedent transcription are associated with poor prognosis of ER+ breast tumors. FASEB J 27:942–954. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-209346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Giorgio E, Clocchiatti A, Piccinin S, Sgorbissa A, Viviani G, Peruzzo P, Romeo S, Rossi S, Dei Tos AP, Maestro R, Brancolini C. 2013. MEF2 is a converging hub for histone deacetylase 4 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-induced transformation. Mol Cell Biol 33:4473–4491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01050-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barneda-Zahonero B, Román-González L, Collazo O, Rafati H, Islam ABMMK, Bussmann LH, di Tullio A, De Andres L, Graf T, López-Bigas N, Mahmoudi T, Parra M. 2013. HDAC7 is a repressor of myeloid genes whose downregulation is required for transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages. PLoS Genet 9:e1003503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons GE, Micales BK, Schwarz J, Martin JF, Olson EN. 1995. Expression of mef2 genes in the mouse central nervous system suggests a role in neuronal maturation. J Neurosci 15:5727–5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Radford JC, Ragusa MJ, Shea KL, McKercher SR, Zaremba JD, Soussou W, Nie Z, Kang Y-J, Nakanishi N, Okamoto S, Roberts AJ, Schwarz JJ, Lipton SA. 2008. Transcription factor MEF2C influences neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and maturation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:9397–9402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802876105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu N, Nelson BR, Bezprozvannaya S, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. 2014. Requirement of MEF2A, C, and D for skeletal muscle regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4109–4114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401732111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilker PR, Kohyama M, Sandau MM, Albring JC, Nakagawa O, Schwarz JJ, Murphy KM. 2008. Transcription factor Mef2c is required for B cell proliferation and survival after antigen receptor stimulation. Nat Immunol 9:603–612. doi: 10.1038/ni.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki E, Guo K, Kolman M, Yu YT, Walsh K. 1995. Serum induction of MEF2/RSRF expression in vascular myocytes is mediated at the level of translation. Mol Cell Biol 15:3415–3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han TH, Prywes R. 1995. Regulatory role of MEF2D in serum induction of the c-jun promoter. Mol Cell Biol 15:2907–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato Y, Kravchenko VV, Tapping RI, Han J, Ulevitch RJ, Lee JD. 1997. BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J 16:7054–7066. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendoza-Maldonado R, Paolinelli R, Galbiati L, Giadrossi S, Giacca M. 2010. Interaction of the retinoblastoma protein with orc1 and its recruitment to human origins of DNA replication. PLoS One 5:e13720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paroni G, Mizzau M, Henderson C, Del Sal G, Schneider C, Brancolini C. 2004. Caspase-dependent regulation of histone deacetylase 4 nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling promotes apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell 15:2804–2818. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson CJ, Aleo E, Fontanini A, Maestro R, Paroni G, Brancolini C. 2005. Caspase activation and apoptosis in response to proteasome inhibitors. Cell Death Differ 12:1240–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frescas D, Pagano M. 2008. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. 1999. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol 1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinissen MJ, Chiariello M, Pallante M, Gutkind JS. 1999. A network of mitogen-activated protein kinases links G protein-coupled receptors to the c-jun promoter: a role for c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, p38s, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5. Mol Cell Biol 19:4289–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Wu G, Li W, Lobur D, Wan Y. 2007. Cdh1-anaphase-promoting complex targets Skp2 for destruction in transforming growth factor beta-induced growth inhibition. Mol Cell Biol 27:2967–2979. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01830-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu ZK, Gervais JL, Zhang H. 1998. Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold MA, Kim Y, Czubryt MP, Phan D, McAnally J, Qi X, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. 2007. MEF2C transcription factor controls chondrocyte hypertrophy and bone development. Dev Cell 12:377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertoli C, Skotheim JM, de Bruin RA. 2013. Control of cell-cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14:518–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan CH, Morrow JK, Li CF, Gao Y, Jin G, Moten A, Stagg LJ, Ladbury JE, Cai Z, Xu D, Logothetis CJ, Hung MC, Zhang S, Lin HK. 2013. Pharmacological inactivation of Skp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase restricts cancer stem cell traits and cancer progression. Cell 154:556–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Johns DC, Geiman DE, Marban E, Dang DT, Hamlin G, Sun R, Yang VW. 2001. Krüppel-like factor 4 (gut-enriched Krüppel-like factor) inhibits cell proliferation by blocking G1/S progression of the cell-cycle. J Biol Chem 276:30423–30428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101194200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J, Lingrel JB. 2004. KLF2 inhibits Jurkat T leukemia cell growth via up-regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1. Oncogene 23:8088–8096. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, et al. 2012. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zentner GE, Tesar PJ, Scacheri PC. 2011. Epigenetic signatures distinguish multiple classes of enhancers with distinct cellular functions. Genome Res 21:1273–1283. doi: 10.1101/gr.122382.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng M, Zhu J, Lu T, Liu L, Sun H, Liu Z, Tian J. 2013. P300-mediated histone acetylation is essential for the regulation of gata4 and MEF2C by BMP2 in H9c2 cells. Cardiovasc Toxicol 13:316–322. doi: 10.1007/s12012-013-9212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDermott JC, Cardoso MC, Yu YT, Andres V, Leifer D, Krainc D, Lipton SA, Nadal-Ginard B. 1993. hMEF2C gene encodes skeletal muscle- and brain-specific transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol 13:2564–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karamboulas C, Dakubo GD, Liu J, De Repentigny Y, Yutzey K, Wallace VA, Kothary R, Skerjanc IS. 2006. Disruption of MEF2 activity in cardiomyoblasts inhibits cardiomyogenesis. J Cell Sci 119:4315–4321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbosa AC, Kim M-S, Ertunc M, Adachi M, Nelson ED, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. 2008. MEF2C, a transcription factor that facilitates learning and memory by negative regulation of synapse numbers and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802679105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canté-Barrett K, Pieters R, Meijerink JPP. 2014. Myocyte enhancer factor 2C in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Oncogene 33:403–410. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark RI, Tan SWS, Péan CB, Roostalu U, Vivancos V, Bronda K, Pilátová M, Fu J, Walker DW, Berdeaux R, Geissmann F, Dionne MS. 2013. XMEF2 is an in vivo immune-metabolic switch. Cell 155:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan SF, Sances S, Brill LM, Okamoto S-I, Zaidi R, McKercher SR, Akhtar MW, Nakanishi N, Lipton SA. 2014. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of MEF2D promotes neuronal survival after DNA damage. J Neurosci 34:4640–4653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2510-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavanaugh JE, Ham J, Hetman M, Poser S, Yan C, Xia Z. 2001. Differential regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK1/2 and ERK5 by neurotrophins, neuronal activity, and cAMP in neurons. J Neurosci 21:434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magli A, Angelelli C, Ganassi M, Baruffaldi F, Matafora V, Battini R, Bachi A, Messina G, Rustighi A, Del Sal G, Ferrari S, Molinari S. 2010. Proline isomerase pin1 represses terminal differentiation and myocyte enhancer factor 2C function in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem 285:34518–34527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Postigo AA, Dean DC. 1999. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell 98:859–869. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anders L, Ke N, Hydbring P, Choi YJ, Widlund HR, Chick JM, Zhai H, Vidal M, Gygi SP, Braun P, Sicinski P. 2011. A systematic screen for CDK4/6 substrates links FOXM1 phosphorylation to senescence suppression in cancer cells. Cancer Cell 20:620–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang M, Truscott J, Davie J. 2013. Loss of MEF2D expression inhibits differentiation and contributes to oncogenesis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Mol Cancer 12:150. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Jenkins CW, Nichols MA, Xiong Y. 1994. Cell-cycle expression and p53 regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Oncogene 9:2261–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckner R, Yao TP, Oldread E, Livingston DM. 1996. Interaction and functional collaboration of p300/CBP and bHLH proteins in muscle and B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev 10:2478–2490. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slepak TI, Webster KA, Zang J, Prentice H, O'Dowd A, Hicks MN, Bishopric NH. 2001. Control of cardiac-specific transcription by p300 through myocyte enhancer factor-2D. J Biol Chem 276:7575–7585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molinari S, Relaix F, Lemonnier M, Kirschbaum B, Schäfer B, Buckingham M. 2004. A novel complex regulates cardiac actin gene expression through interaction of Emb, a class VI POU domain protein, MEF2D, and the histone transacetylase p300. Mol Cell Biol 24:2944–2957. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2944-2957.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto T, Ebisuya M, Ashida F, Okamoto K, Yonehara S, Nishida E. 2006. Continuous ERK activation downregulates antiproliferative genes throughout G1 phase to allow cell-cycle progression. Curr Biol 16:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao W, Zhao SP, Peng DQ. 2012. The effects of myocyte enhancer factor 2A gene on the proliferation, migration and phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Biochem Funct 30:108–113. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skotheim JM, Di Talia S, Siggia ED, Cross FR. 2008. Positive feedback of G1 cyclins ensures coherent cell-cycle entry. Nature 454:291–296. doi: 10.1038/nature07118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.