Abstract

Cell–matrix interaction is required for tissue development. Laminin, a major constituent of the basement membrane, is important for structural support and as a ligand in tissue development. Laminin has 19 isoforms, which are determined by combinational assembly of five α, three β, and three γ chains (eg, laminin 121 is α1, β2, and γ1). However, no report has identified the laminin isoforms expressed during pituitary development. We used in situ hybridization to investigate all laminin chains expressed during rat anterior pituitary development. The α5 chain was expressed during early pituitary development (embryonic day 12.5–15.5). Expression of α1 and α4 chains was noted in vasculature cells at embryonic day 19.5, but later diminished. The α1 chain was re-expressed in parenchymal cells of anterior lobe from postnatal day 10 (P10), while the α4 chain was present in vasculature cells from P30. The α2 and α3 chains were transiently expressed in vasculature cells and anterior lobe, respectively, only at P30. Widespread distribution of β and γ chains was also observed during development. These findings suggest that numerous laminin isoforms are involved in anterior pituitary gland development and that alteration of the expression pattern is required for proper development of the gland.

Keywords: pituitary development, basement membrane, laminin, in situ hybridization

I. Introduction

Tissue development is regulated by numerous factors, including cell–cell and cell–matrix interaction. The basement membrane is a specialized extracellular matrix that is important in tissue development [13, 29]. One of its roles is maintenance of tissue architecture and integrity through cell–basement membrane interaction, as described by Yurchenco [30]. Laminin is a major component of the basement membrane and is primarily responsible for this function, as its N-terminal domain initiates basement membrane assembly [14, 21]. In addition to structural support, laminin acts as a ligand that binds cell surface receptors to regulate cellular activities [25].

Laminin is a cross-shaped molecule composed of α, β, and γ chains [24]. Durbeej [6] reported that it comprises five α, three β, and three γ chains, which assemble into 19 different laminin isoforms, depending on their combination (eg, the laminin isoform comprising the α1, β2, and γ1 chains is referred to as laminin 121 according to the nomenclature proposed by Aumailley et al. [2]). Recently, we found that, in adult rat anterior pituitary, gonadotrophs produce laminin 111 and 121, while endothelial cells produce laminin 411 and 311 [20]. Our research group also showed that laminin facilitates proliferation and motility of folliculostellate cells, ie, non-granulated cells, in anterior pituitary gland [10, 11]. Since pituitary development results from integration of cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation, it is essential to consider whether certain laminin isoforms contribute to these events. However, no report has identified the laminin isoforms expressed during different developmental stages of the anterior pituitary gland. Here, we used in situ hybridization to investigate the expression and localization of laminin chains during the development of rat pituitary gland.

II. Materials and Methods

Animals

Wistar rats were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The animals were given conventional food and water ad libitum and were kept under a 12 hr light/12 hr dark cycle. Room temperature was maintained at approximately 22°C. All animal experiments were performed after receiving approval from the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee of the Jichi Medical University and were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Regulations for Animal Experiments and Fundamental Guideline for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions, under the jurisdiction of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Tissue preparation

To obtain samples at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5), E15.5, and E19.5, pregnant rats were decapitated after deep anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (Kyoritsu Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan), and the heads of embryos were fixed with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.025 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, at 4°C overnight. For samples at postnatal day 5 (P5), P10, and P30, rats were decapitated, and dissected pituitaries were fixed in 4% PFA in 0.05 M PB, pH 7.4, at 4°C overnight. All samples were mixed-sex, except for P30 (which only included males). They were transferred into 30% sucrose in 0.05 M PB buffer, pH 7.2, at 4°C and incubated for 2 days. Tissues were then embedded in Tissue-Tek compound (Sakura Finetechnical, Tokyo, Japan) and frozen rapidly. A cryostat (CM3000; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to make sections (thickness, 8 μm; sagittal sections for prenatal samples and frontal sections for postnatal samples).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization for each laminin chain was performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, to make complementary RNA (cRNA), DNA fragments were amplified from cDNA of adult rat pituitary using gene-specific primers (for primer information, see [20]). A BLAST search to verify the specificity of probe sequences confirmed that each probe sequence was specific to the target gene. DNA fragments were ligated into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) and cloned. Gene-specific antisense or sense digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled cRNA probes were made by using a Roche DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). DIG-labeled cRNA probe hybridization was performed at 55°C for 16–18 hr. Each mRNA type was visualized with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Roche Diagnostics) by using 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche Diagnostics). Sections treated with DIG-labeled sense RNA probes were used as a negative control to confirm probe specificity. No signal was detected in any sense probes. Sections were observed using an AX-80 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

III. Results

To identify the laminin chains present in the prenatal (E12.5, E15.5, and E19.5) and postnatal (P5, P10, and P30) pituitary gland, we performed in situ hybridization for all laminin chains, using specific cRNA probes. All signals of α, β, and γ chains were observed in the cytoplasm. The expression and localization of each laminin chain are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 .

Expression and localization of laminin chains in prenatal and postnatal stages of rat pituitary gland

| Stage | Location | α chain | β chain | γ chain | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E12.5 | Epithelial cell layer of Rathke’s pouch | α5 | β1 | β2 | β3 | γ1 | γ2 | γ3 | ||||

| E15.5 | Pars distalis | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||

| Pars intermedia | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | |||||||

| Pars tuberalis | α5 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||||

| E19.5 | Parenchymal cells (AL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||

| Marginal cell layer (AL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | |||||||

| Marginal cell layer (IL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | |||||||

| Vasculatures (AL) | α1 | α4 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||

| P5 | Parenchymal cells (AL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||

| Marginal cell layer (AL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ2 | ||||||||

| Marginal cell layer (IL) | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | ||||||||

| Vasculatures (AL) | ||||||||||||

| P10 | Parenchymal cells (AL) | α1 | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | |||||

| Marginal cell layer (AL) | α5 | β2 | γ1 | |||||||||

| Marginal cell layer (IL) | α5 | β2 | γ1 | |||||||||

| Vasculatures (AL) | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||||

| P30 | Parenchymal cells (AL) | α1 | α3 | α5 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||

| Marginal cell layer (AL) | α3 | α5 | β1 | γ1 | ||||||||

| Marginal cell layer (IL) | α3 | α5 | β1 | γ1 | ||||||||

| Vasculatures (AL) | α2 | α4 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | γ2 | ||||||

| P60* | Parenchymal cells (AL) | α1 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | |||||||

| Marginal cell layer (AL) | ||||||||||||

| Marginal cell layer (IL) | ||||||||||||

| Vasculatures (AL) | α3 | α4 | β1 | β2 | γ1 | |||||||

AL: Anterior lobe, IL: Intermediate lobe, Blank: Not detected.

*Data are from Ramadhani et al. 2012.

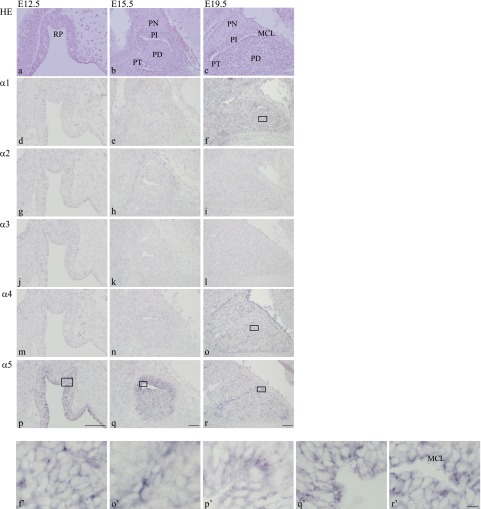

Prenatal laminin chain expression

At E12.5, epithelium cells of oral ectoderm were invaginated to form Rathke’s pouch (the origin of the adenohypophysis) and stratified (Fig. 1a). At this stage, only α5 mRNA was intensely expressed in apical cells and weakly expressed in cells near the basal to intermediate layers of epithelia (Fig. 1p, p’). In contrast, α1–4 mRNAs were not detectable in any cell of the pouch (Fig. 1d, g, j, m). All β1–3 and γ1–3 mRNAs were expressed in epithelial cells of the pouch, as summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1. .

Identification of laminin α chains in prenatal rat anterior pituitary development. Sagittal sections show developing anterior pituitary at E12.5 (a, d, g, j, m, p), E15.5 (b, e, h, k, n, q), and E19.5 (c, f, i, l, o, r). Hematoxylin and eosin staining is shown in a–c. In situ hybridization of laminin α1, α2, α3, α4, and α5 chains is shown in (d–f), (g–i), (j–l), (m–o), and (p–r), respectively. Positive signals of laminin α chains are seen in the cytoplasm of cells (purple); bars=100 μm. Higher magnification views of the boxes in f, o, p, q, and r are shown in f’, o’, p’, q’, and r’, respectively; bar=10 μm. RP: Rathke’s pouch, PN: pars nervosa, PI: pars intermedia, PT: pars tuberalis, PD: pars distalis, MCL: marginal cell layer.

At E15.5, the adenohypophysis differentiated into the pars distalis, pars intermedia, and pars tuberalis (Fig. 1b). At this point, α5 mRNA was intensely expressed in cells of the pars distalis and pars intermedia and weakly expressed in cells of the pars tuberalis (Fig. 1q, q’). As at E12.5, α1–4 mRNAs were not detected in any part of the developing pituitary gland (Fig. 1e, h, k, n). As shown in Table 1, β1 was expressed in some parenchymal cells of the pars distalis. β2 and γ1–2 mRNAs were detected in some parenchymal cells of the pars distalis, pars intermedia, and pars tuberalis, whereas expression of β3 and γ3 mRNAs had diminished at this stage.

At E19.5, the vasculature had invaded the adenohypophysis, and the marginal cell layer was clearly distinguishable around the remnant lumen of Rathke’s pouch (Fig. 1c). Expression of α5 mRNA was intense in apical cells of the marginal cell layer and in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe (Fig. 1r, r’). α1 and α4 mRNAs were strongly expressed in cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe (Fig. 1f, f’, o, o’), whereas α2–3 mRNAs were not detected in any part of the gland (Fig. 1i, l). Expression of β1–3 and γ1–3 mRNAs is summarized in Table 1. β1–2 and γ1–2 mRNAs were detected in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, cells in the marginal cell layer (both anterior and intermediate lobes), and cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe. No expression of β3 or γ3 mRNAs was detected at this stage.

Postnatal laminin chain expression

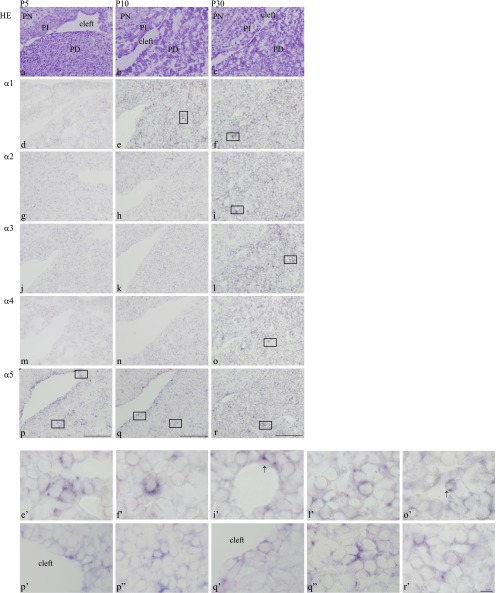

At P5, expression of α5 mRNA was sustained in cells of the marginal cell layer (in both the anterior and intermediate lobes) and in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe (Fig. 2p, p’, p”). However, the signals were lower than in the prenatal stage. No expression of α1–4 mRNAs was detected in the gland at P5 (Fig. 2d, g, j, m), although α1 and α4 mRNAs were observed in vasculature cells at E19.5 (Fig. 1f, f’, o, o’). Expression of β1–3 and γ1–3 mRNAs is summarized in Table 1. β1–2 mRNAs were expressed in cells of the marginal cell layer (in both the anterior and intermediate lobes) and in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, but not in vasculature cells. Expression of γ1 mRNA was detected in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe and in cells of the marginal cell layer (intermediate lobe), whereas γ2 mRNA was detected in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe and in cells of the marginal cell layer (anterior lobe). Laminin β3 and γ3 mRNAs were not detected in the gland at this stage.

Fig. 2. .

Identification of laminin α chains in postnatal rat anterior pituitary development. Frontal sections show the anterior pituitary at P5 (a, d, g, j, m, p), P10 (b, e, h, k, n, q), and P30 (c, f, i, l, o, r). Hematoxylin and eosin staining is shown in a–c. In situ hybridization of laminin α1, α2, α3, α4, and α5 chains is shown in (d–f), (g–i), (j–l), (m–o), and (p–r), respectively. Positive signals of laminin α chains are seen in the cytoplasm of cells (purple); bars=100 μm. Higher magnification views of the boxes in e, f, i, l, o, p, q, and r are shown in e’, f’, i’, l’, o’, p’, p”, q’, q”, and r’, respectively; bar=10 μm. PN: pars nervosa, PI: pars intermedia, PT: pars tuberalis, PD: pars distalis, arrows: labelled cells in vasculature.

At P10, expression of α5 mRNA was similar to that at P5 (Fig. 2q, q’, q”). Laminin α1 mRNA was re-expressed in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe (Fig. 2e, e’), but no signal was detected for α2–4 mRNAs (Fig. 2h, k, n). As summarized in Table 1, β1 and γ2 mRNAs were also expressed in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe and in cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe, but not in cells from the marginal cell layer. Expression of β2 and γ1 mRNAs was detected in all parts of the gland (some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, cells of the marginal cell layer, and cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe), while β3 and γ3 mRNAs were not detected in the gland.

At P30, α1–5 mRNAs were detected as follows: the positive signal for α5 mRNA was weaker in cells of the marginal cell layer and in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, as compared with signals at P5 and P10 (Fig. 2r, r’). Expressions of α2 and α4 mRNA were intensely and specifically expressed in cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe (Fig. 2i, i’, o, o’), while α1 mRNA was strongly detected in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe (Fig. 2f, f’). Expression of α3 mRNA was first expressed in some parenchymal cells and cells of the marginal cell layer (in both the anterior and intermediate lobes) (Fig. 2l, l’). Expression of β1–3 and γ1–3 mRNAs is summarized in Table 1. Laminin β1 and γ1 mRNAs were detected in all parts of the gland (in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, cells of the marginal cell layer, and cells of the vasculature of the anterior lobe), whereas β2 and γ2 mRNAs were expressed in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe and in vasculature cells of the anterior lobe, but not in cells of the marginal cell layer. Expression of β3 and γ3 mRNA was not detectable in any part of the pituitary gland.

IV. Discussion

Using in situ hybridization we identified the laminin chains present in the prenatal and postnatal stages of rat anterior pituitary glands. The laminin isoforms containing α5 were exclusively expressed in the early prenatal stage of anterior pituitary development. Other laminin isoforms were expressed mainly in the postnatal stage of anterior pituitary development: namely, laminin isoforms containing α1 were expressed in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, the α2 and α4 chains in vasculature cells, and α3 in parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe and in cells of the marginal cell layer of the intermediate lobe. Thus, multiple laminin isoforms were involved in the developing anterior pituitary, and expression levels differed by developmental stage.

It has been reported that, in some tissues, laminin isoforms are spatiotemporally regulated and that expression levels change during development [25]. For instance, in the glomerulus, laminin 111 is involved during early glomerulogenesis and then replaced by laminin 511 and 521 during the process of glomerular maturation; only laminin 521 remains in the mature glomerulus [15]. In skeletal muscle, laminin 111 is expressed during the developmental stage and is then changed to laminin 211 at the adult stage [17, 18]. Aumailley et al. [1] hypothesized that the structural and functional properties of laminin are changed by alterations in the combination of the α, β, and γ chains and that these alterations contribute to proper tissue development. Among the 3 laminin chains, the α chain is thought to be the major determinant of laminin structure and function, since it is largely responsible for cell surface adhesion and receptor interactions [30] and is required for laminin secretion [28]. Thus, the expected functions of the laminin isoforms in this study are discussed below in relation to the α chain.

Laminin isoforms containing α5 are commonly expressed in adult tissues, including the lung and kidney [19, 22]. Interestingly, the present study revealed that laminin isoforms containing α5 are the first isoforms expressed during anterior pituitary development (at E12.5) and are expressed before differentiation of hormone-producing cells in rat anterior pituitary (at E13) [16]. During organogenesis, laminin isoforms containing α5 are believed to increase the structural integrity of the basement membrane [23]. Therefore, these isoforms might support initial invagination of the oral ectoderm and subsequent formation of the pituitary anlage. In the present study, we also found that these isoforms were strongly expressed in cells of the marginal cell layer during the postnatal stages. The marginal cell layer is formed by epithelial cells that encircle the residual lumen of Rathke’s pouch and contains undifferentiated cells [7, 26, 27]. Because recombinant laminin containing α5 is involved in self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells [5], it is possible that laminin isoforms containing α5 are required for maintenance of undifferentiated cells in the anterior pituitary gland.

The expression of laminin isoforms containing α1 was unique during pituitary gland development. Briefly, isoforms were first expressed in vasculature cells of the anterior lobe at E19.5 (Fig. 1f, f’). They disappeared shortly thereafter and were then re-expressed in some parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe from P10 to P30 (Fig. 2e, e’, f, f’). This is the first report to show that laminin-producing cells in the same tissue are altered during development. Our previous study showed that, at P60, the laminin α1 chain was produced only by gonadotrophs [20]; thus, it is likely that cells producing the laminin α1 chain from P10 to P30 are gonadotrophs. In rat anterior pituitary, gonadotroph maturation occurred after the first postnatal week [4], which suggests that maturing/matured gonadotrophs produce laminin isoforms containing laminin α1.

Laminin isoforms containing the α4 chain are generally produced by vascular endothelial cells [8]. Consistent with this observation, the present study noted expression of the α4 chain in vasculature cells at E19.5. Interestingly, in the anterior pituitary gland the α4 chain was not expressed at P5 or P10 (Fig. 2m, n) and was re-expressed in the vasculature at P30 until P60 (Fig. 2o, o’; Table 1). Temporal alteration of α4 chain expression has not been reported during vascular development in other tissues; therefore, this phenomenon might be associated with distinct vascular development and maturation in the pituitary gland. Our group showed that only a partial basement membrane was present in the rat anterior pituitary at P5 and that it gradually formed an intact vascular basement membrane until P30 [12]. We speculate that incomplete vascular basement membrane formation at the early postnatal stage is due to the loss of expression of laminin isoforms containing α4 and that re-expression during the late postnatal stage is required for completion of vascular basement membrane formation.

At P30, we observed transient expression of laminin isoforms containing α2 and α3 in vasculature cells and parenchymal cells of the anterior lobe, respectively. Some reports showed that laminin 211 and 221 are involved in the strength and stability of the basement membrane in skeletal muscle [17] and that laminin 332 is involved in cell migration and adhesion in epithelial cells of skin [9]. However, further study is required in order to understand the physiological significance of these isoforms at this specific stage of anterior pituitary development.

In conjunction with alteration of α chain expression, the present study showed that expressions of the β and γ chains also varied during anterior pituitary gland development (Table 1). In addition to the α chain, the β and γ chains are required for self-assembly in the formation of the basement membrane [3]. Cheng et al. [3] proposed a model in which assembly of the α chain with the β and γ chains led to further diversification of the functions of laminin isoforms, as the β and γ chains have varied binding sites. Proper spatiotemporal expression of the β and γ chains might also be important in the development of the pituitary gland.

In conclusion, the different laminin isoforms expressed during each developmental stage may have distinct structural and functional effects on the basement membrane and contribute to development of hormone-producing cells and stromal cells in the anterior pituitary gland. Further studies are needed in order to clarify the mechanisms involved.

V. Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest that might prejudice the impartiality of this research.

VI. Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to declare.

VII. Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Naoki Murayama (Murayama Foundation) for his generous support and David Kipler, ELS (Supernatant Communications) for revising the language of the manuscript. This work was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (22590192), by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (23790233) (25860147) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and by promotional funds for the Keirin Race of the Japan Keirin Association.

VIII. References

- 1.Aumailley M. (2013) The laminin family. Cell Adh. Migr. 7; 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aumailley M., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Carter W. G., Deutzmann R., Edgar D., Ekblom P., Engel J., Engvall E., Hohenester E., Jones J. C., Kleinman H. K., Marinkovich M. P., Martin G. R., Mayer U., Meneguzzi G., Miner J. H., Miyazaki K., Patarroyo M., Paulsson M., Quaranta V., Sanes J. R., Sasaki T., Sekiguchi K., Sorokin L. M., Talts J. F., Tryggvason K., Uitto J., Virtanen I., Von der Mark K., Wewer U. M., Yamada Y. and Yurchenco P. D. (2005) A simplified laminin nomenclature. Matrix Biol. 24; 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Y. S., Champliaud M. F., Burgeson R. E., Marinkovich M. P. and Yurchenco P. D. (1997) Self-assembly of laminin isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 272; 31525–31532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs G., Ellison D., Foster L. and Ramaley J. A. (1981) Postnatal maturation of gonadotropes in the male rat pituitary. Endocrinology 109; 1683–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domogatskaya A., Rodin S., Boutaud A. and Tryggvason K. (2008) Laminin-511 but not -332, -111, or -411 enables mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal in vitro. Stem Cells 26; 2800–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durbeej M. (2010) Laminins. Cell Tissue Res. 339; 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gremeaux L., Fu Q., Chen J. and Vankelecom H. (2012) Activated phenotype of the pituitary stem/progenitor cell compartment during the early-postnatal maturation phase of the gland. Stem Cells Dev. 21; 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallmann R., Horn N., Selg M., Wendler O., Pausch F. and Sorokin L. M. (2004) Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 85; 979–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamill K. J., Paller A. S. and Jones J. C. R. (2010) Adhesion and migration, the diverse functions of the laminin α3 subunit. Dermatol. Clin. 28; 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horiguchi K., Kikuchi M., Kusumoto K., Fujiwara K., Kouki T., Kawanishi K. and Yashiro T. (2010) Living-cell imaging of transgenic rat anterior pituitary cells in primary culture reveals novel characteristics of folliculo-stellate cells. J. Endocrinol. 204; 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horiguchi K., Ilmiawati C., Fujiwara K., Tsukada T., Kikuchi M. and Yashiro T. (2012) Expression of chemokine CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 in folliculostellate (FS) cells of the rat anterior pituitary gland: the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis induces interconnection of FS cells. Endocrinology 153; 1717–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jindatip D., Fujiwara K., Horiguchi K., Tsukada T., Kouki T. and Yashiro T. (2013) Changes in fine structure of pericytes and novel desmin-immunopositive perivascular cells during postnatal development in rat anterior pituitary gland. Anat. Sci. Int. 88; 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruegel J. and Miosge N. (2010) Basement membrane components are key players in specialized extracellular matrices. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67; 2879–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S., Edgar D., Fassler R., Wadsworth W. and Yurchenco P. D. (2003) The role of laminin in embryonic cell polarization and tissue organization. Dev. Cell 4; 613–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miner J. H. (2008) Laminins and their roles in mammals. Microsc. Res. Techniq. 71; 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeskéri A., Sétáló G. and Halász B. (1988) Ontogenesis of the three parts of the fetal rat adenohypophysis. A detailed immunohistochemical analysis. Neuroendocrinology 48; 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton B. L. (2000) Laminins of the neuromuscular system. Microsc. Res. Techniq. 51; 247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedrosa-Demellof F., Tiger C. F., Virtanen I., Thornell L. E. and Gullberg D. (2000) Laminin chains in developing and adult human myotendinous junctions. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 48; 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce R. A., Griffin G. L., Miner J. H. and Senior R. M. (2000) Expression patterns of laminin α1 and α5 in human lung during development. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 23; 742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramadhani D., Tsukada T., Fujiwara K., Horiguchi K., Kikuchi M. and Yashiro T. (2012) Laminin isoforms and laminin-producing cells in rat anterior pituitary. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 45; 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schittny J. C. and Yurchenco P. D. (1990) Terminal short arm domains of basement membrane laminin are critical for its self-assembly. J. Cell Biol. 110; 825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorokin L. M., Pausch F., Durbeej M. and Ekblom P. (1997) Differential expression of five laminin alpha (1–5) chains in developing and adult mouse kidney. Dev. Dyn. 210; 446–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spenle C., Simon-Assmann P., Orend G. and Miner J. H. (2013) Laminin α5 guides tissue patterning and organogenesis. Cell Adh. Migr. 7; 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timpl R., Rohde H., Gohren R. P., Rennard S. L., Foidart J. M. and Martin G. R. (1979) Laminin—A glycoprotein from basement membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 254; 9933–9937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzu J. and Marinkovich M. P. (2008) Bridging structure with function: structural, regulatory, and developmental role of laminin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B. 40; 199–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yako H., Kato T., Yoshida S., Higuchi M., Chen M., Kanno N., Ueharu H. and Kato Y. (2013) Three-dimensional studies of Prop1-expressing cells in the rat pituitary just before birth. Cell Tissue Res. 354; 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura F., Soji T. and Kiguchi Y. (1977) Relationship between the follicular cells and marginal layer cells of the anterior pituitary. Endocrinol. Jpn. 24; 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yurchenco P. D., Quan Y., Colognato H., Mathus T., Harrison D., Yamada Y. and O’Rear J. J. (1997) The α chain of laminin-1 is independently secreted and drives secretion of its β- and γ-chain partners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 94; 10189–10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yurchenco P. D., Cheng Y., Campbell K. and Li S. (2004) Loss of basement membrane, receptor and cytoskeletal lattices in a laminin-deficient muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Sci. 117; 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yurchenco P. D. (2011) Basement membranes: cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3; a004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]