Abstract

Mycoplasma is a virulent organism that is known to primarily infect the respiratory tract; however, affection of the skin, nervous system, kidneys, heart and bloodstream has been observed in various forms, which include Stevens Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, encephalitis, renal failure, conduction system abnormalities and hemolytic anemia. Small vessel vasculitis is a lesser-known complication of mycoplasma pneumonia infection. We report a case of mycoplasmal upper respiratory tract infection with striking cutaneous lesions as the presenting symptom. Mycoplasmal infection was confirmed by serology testing, skin biopsy was suggestive of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. This case brings forth an uncommon manifestation of mycoplasmal infection with extra-pulmonary affection, namely small vessel vasculitis.

Key words: leukocytoclastic vasculitis, mycoplasma, small vessel vasculitis

Introduction

Mycoplasma is a virulent organism that is known to primarily infect the respiratory tract; however, affection of the skin, nervous system, kidneys, heart and bloodstream has been observed in various forms, which include Stevens Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, encephalitis, renal failure, conduction system abnormalities and hemolytic anemia. Small vessel vasculitis is a lesser-known complication of mycoplasma pneumonia infection.

Case Report

A previously healthy 24-year-old Hispanic male came to the emergency room complaining of a worsening skin eruption over his legs. He had first complained of a fever, headache, cough and sore throat five days prior to this presentation and was advised symptomatic treatment with benzocaine, acetaminophen and saline gargles for viral pharyngitis. A rapid Strep, monospot test and throat culture were reportedly negative. Three days later, he developed a rash on both his legs and feet, which ascended, towards his buttocks. He began noticing rapidly evolving fluid filled lesions and this prompted him to come in for evaluation. On inquiry, he denied feeling itchy and having had insect bites. He denied any skin exposure to vegetation, seawater, toxic chemicals and new footwear.

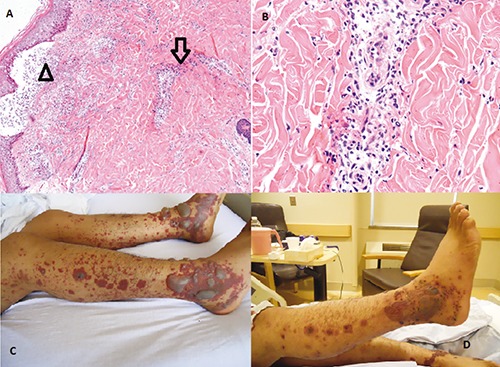

On physical exam, all vital signs were normal. Oral cavity examination showed no ulceration or lesions. No conjunctive chemosis was noted. He was noted to have a diffuse petechial eruption with purpura over his bilateral lower extremities, profound on the anterior aspect of his legs (Figure 1C). This was also noted on the plantar aspect of his feet. Tense fluid filled bullae were noted on his ankles and over the dorsum of both feet. No desquamation was observed. The remainder of the exam was unremarkable. On presentation his white blood cell count was 7.5, platelet count was 417 and C-reactive protein was 159.6. His alanineaminotransferase, aspartate-aminotransferase and Alk Phos levels were all mildly elevated at 95, 42 and 172 respectively. Given his presentation further serology testing was pursued which was as follows. Epstein-Barr virus IgM was <0.91, IgG was positive with a value of >5.00. Mycoplasma IgM was noted to be elevated at 1327 (normal: 0.90-1.09) while IgG was 2.20 (normal: 0.90-1.09). Monospot testing, HIV screening, hepatitis panel, antinuclear antibodies, proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antibodies were all negative. Blood cultures obtained on admission showed no growth after 5 days. Urine analysis was normal.

Figure 1.

A) Skin with epidermal spongiosis, subepidermal vesicles, pustular formation (arrowhead), and leukocytoclastic vasculitis (arrow); B) high power view shows infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, which causes vascular damage; C) gross image of skin findings on admission; D) gross image of skin findings 3 days after the initiation of treatment.

The patient was empirically treated with prednisone, famotidine and hydroxyzine. A skin biopsy was obtained from a lesion on the right medial calf, which showed epidermal spongiosis, subepidermal vesicles and pustules (Figure 1A). Neutrophilic predominance was observed on pathology with rare eosinophils, suggestive of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 1B). Intravenous methylpred-nisolone and colchicine was subsequently started leading to crusting of his bullae and resolution of the petechial rash over the following three days (Figure 1D). Decision was made not to start antibiotics as his upper respiratory symptoms had resolved. On following days C-reactive protein, aspartate-aminotransferase, alanine-aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels trended down to 41.4, 77,35 and 142 respectively and he was discharged from the hospital on day 5. Patient was given tapering dose of oral prednisone for the following 18 days upon discharge. Pertinent differentials were drug induced bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme with bullae and porphyria cutanea tarda all of which were excluded on the skin biopsy.

The patient followed up in the outpatient ambulatory medical clinic following the discharge with in 4 weeks. He had complete resolution of the rash at this time. His blood work on follow-up visit showed improved C-reactive protein of 4.9 and mycoplasma IgM level of 584.

Discussion

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV), also known as hypersensitivity vasculitis and hypersensitivity angiitis, is a histopathologic term commonly used to denote a small-vessel vasculitis.1 LCV is characterized by leukocytoclasis, which refers to vascular damage caused by nuclear debris from infiltrating neutrophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis classically presents as palpable purpura. Less common clinical findings include urticarial plaques, vesicles, bullae, and pustules. This disorder is typically caused by drugs that probably act as haptens to stimulate an immune response. Most commonly implicated medications are penicllins, cephalosporins and sulfonamides.2 Infections such as hepatitis, chronic bacteremias (e.g. endocarditis, infected shunts), and HIV have also been associated with this syndrome.3 In our patient, the vasculitis was associated with an infection with Mycoplasma pneumonia. Other infectious and rheumatic disorders were excluded by appropriate tests.

Mycoplasma pneumonia most commonly causes upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and is also known to cause pneumonia. The onset of illness with mycoplasma is usually heralded by headache, malaise and low-grade fever.4 Infection usually presents with intractable, nonproductive cough with only 3-10% people developing pneumonia.5 Mycoplasma infections have also been noted to present with extra pulmonary manifestations such as those involving the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Neurologic manifestations, such as encephalitis, are usually not accompanied by respiratory symptoms.6 There have been case reports of kidney pediatric population, with renal manifestations occurring after respiratory tract infections.7

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is known for its propensity to cause cutaneous complications. Cutaneous lesions occur in as many as 25% of patients, ranging from erythema to more severe involvement such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Of the dermatologic manifestations, Steven Johnson’s syndrome was noted to be the most common.8 Raynaud phenomenon may also be seen in M. pneumoniae infection, possibly secondary to cold agglutinin formation.9 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumonia has been previously reported in literature as case reports. We performed a thorough search of literature for this association and came up with only rare case reports citing this association.10,11

Based on the rarity of reports LCV is either an uncommon cutaneous complication of mycoplasmal infection or is under diagnosed. The pathogenesis of LCV is not fully understood and has traditionally been considered an inflammation of small vessels that is related to a type III immune complex-mediated hyper-sensitivity reaction.12 In previous reports, it has been suggested that the interplay between autoimmune mechanisms and M. pneumonia antigens could induce vasculitis, but the exact mechanisms remains unknown.10 Presumably, the antibody directed against mycoplasma also attacks the endothelium due to antigen mimicry. This provides a platform for complement linked immune lysis of both the bacteria and endothelium causing vasculitis.11

Our patient was treated with prednisone, famotidine and hydroxyzine, which led to resolution of the petechial rash. The mainstay of therapy for M. pneumoniae infections is a macrolide antibiotic. Our patient was not treated with antibiotics because his upper respiratory tract symptoms had resolved. The recognition of hypersensitivity vasculitis due to an ongoing infection is extremely important since the administration of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may be harmful, as they have been implicated previously for causing LCV.13 Treatment is aimed at the underlying infection. Glucocorticoids can be used in conjunction for cases not responding to the treatment of the underlying infection. In one case report of LCV with encephalitis associated with M. pneumoniae, the patient was treated with amoxicillin and clavulanate and later changed to erythromycin when serology tests were positive for M. pneumoniae. The patient was also treated with prednisone, which resulted to the resolution of the cutaneous lesions and encephalitis.11 Cytotoxic agents should be reserved for the infrequent patient with fulminant or progressive disease.14

Conclusions

In summary, this was a case of infection with Mycoplasma pneumonia presenting with rash due to LCV associated with mild URTI symptoms. It is thus essential for clinicians to keep in mind this association and probably we suggest testing for Mycoplasma pneumonia using mycoplasma serology in patient’s presenting with mild URTI symptoms associated with cutaneous manifestations.

Acknowledgements

the authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Medicine, Department of Pathology and Section of Infectious Diseases at Monmouth Medical Center, New Jersey, USA.

References

- 1.Lie JT. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:181-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calabrese LH, Duna GF. Drug-induced vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1996;8:34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Taboada VM, Blanco R, Garcia-Fuentes M, Rodriguez-Valverde V.Clinical features and outcome of 95 patients with hypersensitivity vasculitis. Am J Med 1997;102:186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luby JP. Pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Chest Med 1991;12:237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansel JK, Rosenow EC, 3rd, Smith TF, Martin JW., Jr Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Chest 1989;95:639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narita M. Pathogenesis neurologic manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Neurol 2009;41:159-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arca M, Bellot A, Dupont C, et al. [Two uncommon extrapulmonary forms of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection]. Arch Pédiatr 2013;20:378-81 [Article in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tay YK, Huff JC, Weston WL. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, not erythema multiforme (von Hebra). J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baum SG. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical pneumonia. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 7th ed.Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. pp 2481. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tr ko K, Marko PB, Miljkovi J.Leukocytoclastic vasculitis induced by Myoplasma pneumoniae infection. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2012;20:119-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez C, Montes M.Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis and encephalitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez EB, Conn DL. Hypersensitivity vasculitis (small-vessel cutaneous vasculitis). Ruddy S, Harris ED, Sledge CB, Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology. 6th ed Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company: 2001. pp 1197-1203. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel CL. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and Henoch-Schönlein purpura. In:Arthritis and allied conditions: a textbook of rheumatology. 15th ed.2005. pp 1793-97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]