Abstract

The goal of cancer treatment is generally pain reduction and function recovery. However, drug therapy does not treat pain adequately in approximately 43% of patients, and the latter may have to undergo a nerve block or neurolysis. In the case reported here, a 42-year-old female patient with lung cancer (adenocarcinoma) developed paraplegia after receiving T8-10 and 11th intercostal nerve neurolysis and T9-10 interlaminar epidural steroid injections. An MRI results revealed extensive swelling of the spinal cord between the T4 spinal cord and conus medullaris, and T5, 7-11, and L1 bone metastasis. Although steroid therapy was administered, the paraplegia did not improve.

Keywords: Intercostal nerve block, Lung cancer pain, Neurolysis, Paraplegia, Spinal cord infarction, Thoracic epidural injection

Inadequate pain relief from systemic medications is common in patients with an advanced malignancy [1]. Chest wall pain caused by tumor involvement in chest wall structures can be challenging to manage with systemic medications, and patients occasionally benefit from interventional procedures such as thoracic epidural block, intercostal nerve block, or neurolysis. We report a case in which a lung cancer patient developed paraplegia after receiving left T8-10 and 11th intercostal nerve neurolysis and T9-10 interlaminar epidural injections.

CASE REPORT

A 42 year-old-woman diagnosed with lung cancer (adenocarcinoma type T4N2M1a, pleural seeding) was admitted to our institution for pleural seeding related to left chest wall pain (T8-11 nerve dermatome) causing respiratory difficulty. One month prior, an enhanced chest and abdomen CT had revealed a collapse of the lower left lung and bilateral lung, and hemithoracic pleural metastasis (the left side showing more severe pleural metastasis), with no bone metastasis (Fig. 1). Following a consultation for pain control, the intercostal nerves in the T8-10 and 11th were blocked with an ultrasound, and there was no motor weakness or side effects. Subsequently, the patient's visual analogue scale score (VAS, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the most severe pain imaginable) dropped from 7-8/10 to 3-4/10 for 3 days. Following her discharge, however, the pain returned with increased severity (VAS 8/10), and she was readmitted through the emergency center. With the aid of an ultrasound, 0.25% chirocaine 2 ml was injected at each level of the T8-10 and 11th intercostal nerve. However, the pain relief did not last longer than two days. Considering that the patient had experienced brief pain relief from the intercostal nerve block, an intercostal nerve neurolysis was scheduled.

Fig. 1. CT image following chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the lung. The CT image shows increased multiple pleuropulmonary metastasis in both hemithoraces, and a small amount of pericardial effusion.

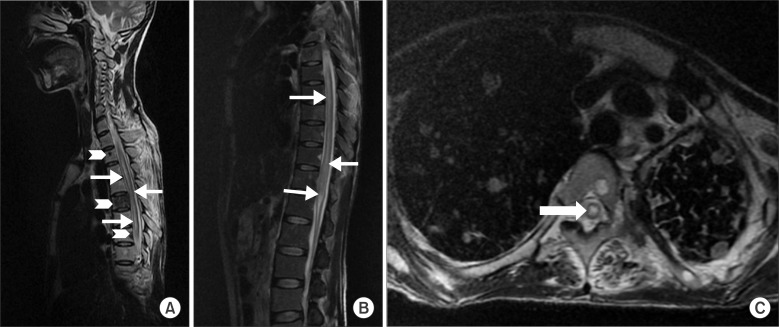

The patient was placed in the prone position on a fluoroscopy-compatible operating table. As alcohol neurolysis could temporarily increase the patient's pain, monitored anesthetic care (MAC) and a thoracic epidural block were also scheduled. Following aseptic preparation and draping, a T8-10 and 11th intercostal nerve neurolysis was conducted using an ultrasound. A 22 G needle was inserted about 5 cm laterally from the lateral tip of each transverse process, under the 8-10 and 11th left ribs. The needle was fixed between the internal intercostal muscle and the innermost intercostal muscle. Following negative blood aspiration, an alcohol 2 ml solution (99.9%) was injected at each level. Then, a C-arm fluoroscopy-guided thoracic epidural injection was performed in the left T9-10 interlaminar space. Using a Tuohy needle, 0.125% chirocaine 8 ml and dexamathasone 5 mg were injected. Upon completion of the procedure, the patient was moved to the recovery room before being transferred to the admission room. After 1 hour, the patient reported bilateral motor weakness to the ward nurse, although her sensory of lower extremities was normal. The nurse believed these symptoms to have been caused by the block and did not consult the pain clinic. About seven hours after the transfer, the patient reported urinary difficulty. The attending physician was notified and the pain clinic was contacted for consultation. Upon physical examination, the neurological tests showed that the upper extremity was intact, but there was significant motor weakness in the lower extremities (hip flexion 0/0, abduction 0/0, adduction 0/0, knee extension 0/0, flexion 0/0, dorsi-flexion 0/0) and a sensory decrease below the L2 level. An epidural hematoma or possible spinal cord infarction were suspected, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was immediately undertaken. The thoracic and lumbar MRI with contrast demonstrated an abnormal spinal cord signal between the T4 spinal cord and the conus medullaris, and bone metastasis at the T5, T7-11, and L1 levels. (Fig. 2) Spinal cord infarction was suspected, and steroid therapy was initiated. Upon physical examination on postoperative day (POD) 5, the patient's entire lower extremity motor grade was 0, and the pinprick and temperature sensitivity were recorded as 0/0 below the T4 level. Despite the intravascular steroid therapy, there was no neurological recovery.

Fig. 2. MRI images following the onset of paraplegia in this case. The CT spine image (A) shows a low-signal intensity, suggesting bone metastasis (chevron). A and B (T-L spine image) show a T2 high-signal intensity from the T4 level to the conus medullaris and a suspected cord infarction (arrow). The T2 weighted axial image (C) shows diffuse cord swelling, another suspected symptom of cord infarction (thick arrow).

On POD 10, the patient became feverish and was diagnosed with pneumonia. She expired from pneumonia complications on POD 22.

DISCUSSION

As many as 43% of patients with malignancies do not experience adequate pain relief from systemic medications [1]. In those patients, the systemic opioid dose must be increased in order to control the pain [2]. However, increases in the systemic opioid dose can also increase the side effects. A plausible interventional approach for patients experiencing the dose-limiting side effects of systemic medications is a nerve block or neurolysis [3]. For chest wall pain caused by a malignancy, an intercostal nerve block is often an option [4,5].

In the present case, we identified three possible reasons for the patient's paraplegia. First, the complications may have been related to the thoracic epidural steroid injection. L. Thefenne et al. encountered a similar case in a 54-year-old male patient who had received right S1 radiculopathy surgery for a L5-S1 slipped disc [6]. Immediately after receiving a lumbar injection with prednisolone 125 mg, the patient developed complete, flaccid motor and sensory paraplegia under the T7 level [6]. T. Adam Oliver et al. also reported the case of a 69-year-old male patient who suffered from lower extremity weakness and paresthesia caused by L2-3 and L3-4 central spinal stenosis, for which he received a L5-S1 interlaminar epidural injection [7]. The reason for his paraplegia after the epidural injection was thought to have been secondary to vascular trauma, vascular spasm, or the injection of particulate steroids into the artery, which may have caused an embolic effect. Although we used non-particulate steroids for the epidural injection and although paraplegia is a very rare complication of epidural injections, there is nevertheless a risk. The second possible cause is an occlusion of the radiculomedullar artery due to hematologic metastasis. There have been a few case reports of paraplegia or neurological deficits following central neuraxial blockades in patients with previously-undiagnosed bone metastases. Kararmaz et al. [8] reported a case of post-operative paraplegia in a previously-undiagnosed case of vertebral metastases originating from endometrial cancer, following a combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Graham et al. [9] also described a case of paraplegia following spinal anesthesia for a bilateral orchidectomy in a case of prostatic carcinoma with spinal metastasis and no pre-existing neurological deficit. As the compliance of the epidural space is restricted by the metastasis, the administration of local anesthetics causes an increase in volume and pressure in the epidural space, leading to symptoms of compressive myelopathy [10]. In our case, the enhanced chest and abdominal CT had shown no evidence of spinal metastasis 1 month prior. However, the MRI taken after the onset of the paraplegia showed multiple spinal metastasis, and there might also have been a risk of embolism by hematologic metastasis.

The third possible reason for the patients' paraplegia may have been complications from the alcohol used in the intercostal nerve neurolysis, and which may have caused spinal cord injury. There has been one case report of paraplegia or neurological deficit following intercostal nerve neurolysis. Roland Kowalewski et al. [11] reported the case of a 55-year-old man with severe scoliosis and chest deformity. The patient was given a 7.5% aqueous phenol solution 6 ml below the 10th rib and 3-4 cm outside the spine midline. A few minutes after the injection, the patient felt a heating sensation in his right leg, and decreased motor and sensory functions in both legs. The cause was the diffusion of the phenol through the intervertebral foraminae, which damaged the motor and sensory roots [11]. Although we used a smaller drug dose than in this report and the injection site was further away from the spine, we did not know the spreading pattern of the alcohol. If the injected alcohol moved through the paravertebral gutter and the intervertebral foraminae into the epidural space, it could have extended into the intrathecal space [12,13].

After looking at other reports of similar cases and comparing them with our patient's MRI and the procedures she underwent, we came to the conclusion that the cause of this patient's paraplegia was most likely to have been spinal cord ischemia, or possibly spinal cord neurolysis. Alcohol mixed with contrast media can be useful to confirm the spread of alcohol under fluoroscopy, and a smaller dose of neurolytic drug may decrease the risk of paraplegia.

Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence as to which of the potential causes discussed above, whether alone or in combination, were responsible for the spinal cord infarction.

Therefore, physicians should always keep a few points in mind when treating patients with lung cancer for pain relief. First, when performing an intercostal nerve neurolysis, the alcohol injection should be located far away from the spine, and a small quantity of alcohol solution should be used. This may reduce the likelihood of complications. However, more research is needed to determine the exact location of the injection or the precise amount to be used. Second, in epidural injections, contrast media is used to track the placement of the needle. Although it may sometimes look as though the tip of the needle is not in the vessel, it is still possible that it may be in the vessel [14]. To evaluate the intravascular injection, a digital subtraction angiography can be useful. One should be particularly aware of this and especially careful with patients presenting a history of spine cancer metastasis or spine surgery, as they may feature changes to the epidural space and potential vessel variations. Third, when performing an intercostal nerve neurolysis, the patient's motor power must be examined after the procedure.

Lastly, if abnormal symptoms such as motor weakness or decreased sensitivity appear after an epidural injection or intercostal nerve neurolysis, a careful physical examination and imaging studies should immediately be taken in order to find the causes of the paraplegia. After identifying the causes, appropriate treatment should be promptly administered in order to minimize the central nerve damage and help the patient recover.

In conclusion, when performing block procedures, physicians should always keep the patients' preexisting conditions as well as the risks of central nerve damage in mind. The possibility of a number of other side effects should also be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This case study is supported by Kunkun University.

References

- 1.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985–1991. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon MI, Kim KS, Shin OY, Oh JY. Effects of intercostal nerve block combined with IV-PCA on postoperative analgesia and pulmonary function recovery after thoracotomy. J Korean Pain Soc. 2002;15:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonica JJ. The management of pain of malignant disease with nerve blocks. Anesthesiology. 1954;15:134–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong FC, Lee TW, Yuen KK, Lo SH, Sze WK, Tung SY. Intercostal nerve blockade for cancer pain: effectiveness and selection of patients. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:266–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolawole IK, Adesina MD, Olaoye IO. Intercostal nerves block for mastectomy in two patients with advanced breast malignancy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:450–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thefenne L, Dubecq C, Zing E, Rogez D, Soula M, Escobar E, et al. A rare case of paraplegia complicating a lumbar epidural infiltration. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:575–583. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver TA, Sorensen M, Arthur AS. Endovascular treatment for acute paraplegia after epidural steroid injection in a patient with spinal dural arteriovenous malformation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:251–255. doi: 10.3171/2012.6.SPINE11835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kararmaz A, Turhanoglu A, Arslan H, Kaya S, Turhanoglu S. Paraplegia associated with combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia caused by preoperatively unrecognized spinal vertebral metastasis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:1165–1167. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham GP, Dent CM, Mathews P. Paraplegia following spinal anaesthesia in a patient with prostatic metastases. Br J Urol. 1992;70:445. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1992.tb15806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Médicis E, de Leon-Casasola OA. Reversible paraplegia associated with lumbar epidural analgesia and thoracic vertebral metastasis. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1316–1318. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowalewski R, Schurch B, Hodler J, Borgeat A. Persistent paraplegia after an aqueous 7.5% phenol solution to the anterior motor root for intercostal neurolysis: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:283–285. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.27477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdalla EK, Schell SR. Paraplegia following intraoperative celiac plexus injection. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:668–671. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell-Jones G, Pither CE, Justins DM. Paravertebral somatic nerve block: a clinical, radiographic, and computed tomographic study in chronic pain patients. Anesth Analg. 1989;68:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin J, Kim YC, Lee SC, Kim JH. A comparison of Quincke and Whitacre needles with respect to risk of intravascular uptake in S1 transforaminal epidural steroid injections: a randomized trial of 1376 cases. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:1241–1247. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a6d1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]