Abstract

Background:

Assessment of patients’ views about the observance of their rights and obtaining feedback from them is an integral component of service quality and ensures healthcare ethics. The aim of this study was to assess patients’ awareness of their rights and their satisfaction with observance of their rights, and provide effective strategies to improve the management of patients’ rights in hospitals of Markazi Province, Iran in 2012.

Materials and Methods:

This analytical study was conducted on 384 patients at 10 hospitals. Patients’ awareness of the relevant hospital legislation was assessed by a structured interview, and then patients’ satisfaction with observance of their rights was measured by a standardized questionnaire consisting of 10 principles approved by the Iran Ministry of Health of Iran in 2012. In this study, through Delphi technique, effective strategies have been provided to improve the management of patients’ rights in the hospitals of Iran. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), t-test, and Z test were applied for data analysis.

Results:

Overall, 89% of the patients were unaware of the relevant hospital legislation and 28% of them were not satisfied with the observance of their rights (1.4 ± 0.6). A significant difference was observed between observance of patients’ rights according to hospitals, language, and place of residence of the patients (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference with respect to patients’ rights according to sex, education, job, and duration of hospital stay (P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

The Patient Bill of Rights of Iran needs further revision and modification. Moreover, extensive education of patients and healthcare processionals as the most structural strategies to promote professional ethics, reduce ethical conflict, and increase implementation of the law to respect patients’ rights should be taken into deeper consideration.

Keywords: Iran, patient rights, satisfaction, strategy

INTRODUCTION

Patient Bill of Rights (PBR) calls for equal rights for all patients to access health services.[1] Patient rights are universal values that have to be adopted.[2] They establish a foundation for preserving good relationships among patients, doctors, and other healthcare providers.[3] Patient rights is considered as a reflection of human rights in the modern day society.[4] It is a recently introduced term in health sciences literature and practice,[5] and the aphorism that patients have needs, not rights, is sometimes a set response to demands for increased patient rights. In fact, patients have both “health” and “life” as the primary values expressed by healthcare professionals and others.[6] Meanwhile, social, economic, cultural, ethical, and political developments, such as population growth and new developments in medical technology,[7,8] increase the awareness and expectations of patients,[9] complexity in healthcare systems, and economic pressures or inflation. These have given rise to a movement in the world toward fuller elaboration and fulfillment of the patients’ rights.[10] Historically, the first texts protecting patients’ rights are Hippocratic in origin, imposing on physicians the respect of patients’ dignity,[11] and legislations on patients’ rights have been passed throughout the world since the Human Rights Act was published by the United Nations in 1948.[12] In 1973, the American Hospital Association (AHA) adopted the first official text of PBR. Since then, protection of patients’ rights has been a focal point in the agenda of many national and international organizations and has become part of national legislation.[13] However, the fundamental reason for the importance attached to patients’ rights and the corresponding increase in legislation is that respecting patients’ rights is an essential part of providing good healthcare.[14] Open and honest communication,[15] respect for personal and professional values,[16] sensitivity to differences, and treatment autonomy are integral to optimal patient care,[17,18] and it is a strategy for guaranteeing continuous quality in healthcare.[19] Respecting patient rights and effective healthcare requires a collaboration among patients, physicians, and other healthcare professions.[20] Research has shown that assessment of patients’ views about the observance of their rights in the healthcare for evaluation of such systems is necessary.[21,22] Therefore, hospitals, both as one of the most important elements of the health service and as an organization, must ensure healthcare ethics[23] and observance of the rights of patients, their families, physicians, and other care providers.[24] On 25 October 2002, the Ministry of Health in Iran adopted 10 principles of patients’ rights and the third edition of the national PBR was published in 2009. Unfortunately, this charter does not cover all patients’ rights compared to what exists in other developed countries.[25] Researches have shown that Iranian patients do not have the right to choose treatment options, be informed of the contents of medical records, participate in clinical decision making, and continue to receive treatment at home.[26] It has been mentioned that 42% of patients in the teaching hospitals in Iran are not satisfied with their participation in clinical decision making and observance of their privacy and confidentiality.[27,28] On the other hand, the ethical difficulties in healthcare have increased in the world, and healthcare providers are involved in recurrent ethical problems.[29] Conducting surveys with respect to patients’ rights and the strategies to reduce ethical conflicts in the hospitals is necessary.[30] Research has shown that using qualitative and quantitative research in ethics, we will be able to deal with problems such as inequities, promotion of healthcare, development institutional ethics, and observance of patient rights.[31]

Recently, patient rights have been gained increasing importance as a major component of system performance by international agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). WHO included an index of responsiveness to the expectations of consumers in its recent health systems in the world.[32]

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess patients’ awareness of their rights, satisfaction with observance of their rights, and provision of effective strategies to improve the management of patients’ rights in hospitals of Markazi Province, Iran in 2012.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To investigate the awareness of and satisfaction with patients’ rights in Iranian hospitals, an analytical study was conducted in January and December 2012. Patients were selected by stratified random sampling of 10 hospitals in Markazi Province. A total of 394 patients were included in the study according to the following criteria: (1) age: 18 years or older; (2) duration of hospital stay: Hospitalization for at least 3 days to enable them to assess their rights; (3) inpatient wards: Patients of intensive care unit (ICU), critical care unit (CCU), and hemodialysis wards were excluded because they were in certain conditions. Patients’ awareness of their relevant hospital legislation was assessed by a structured interview, and then patients’ satisfaction of observance of their rights was measured by a standardized questionnaire with 10 principles approved by the Iran Ministry of Health in 2002.[25] Initially, to avoid bias, an interview with patients about their knowledge of their rights was carried out, and 1 hour later, observance of their rights was assessed by a questionnaire with 20 questions. The structured interview and the completion of the questionnaire lasted 30-35 min. The Likert-type questionnaire consisted of 15 closed questions on the observance of patients’ rights and 5 open questions on the mechanisms of protection of their rights and the weaknesses\and strengths of the hospitals. The patients were asked to rate their responses to questions on observance of their rights on a 5-point scale (1 for “strongly disagree” and 5 for “strongly agree”). The questionnaire was composed of 10 principles of patients’ rights in Iran. These rights which are approved by the Iran Ministry of Health include the right of privacy and confidentiality, explanation of common risks and side effects, providing sufficient information about the disease and diagnosis, obtaining informed consent, introducing the doctor and the nurse to the patient, respectful provision of healthcare, provision of equitable access to healthcare service, provision of sufficient information about medical costs and insurance, denial of access to medical records except for the care providers, observance of patients’ diet, getting clear answers to questions from the treatment team, recognizing the healthcare provision team, access to physician and nurses, and seeking the opinions of patients about clinical research.[26,27] A pilot study was conducted with 35 patients of similar status, which proved the validity, the easy-to-use format, and the understandable nature of the questionnaire. The reliability of this questionnaire was examined using Cronbach's alpha (0.83).

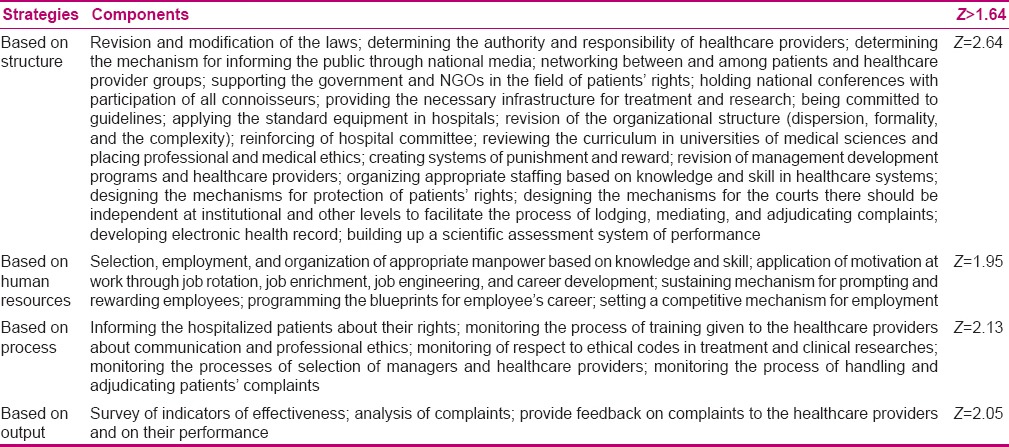

In the second phase of this study, in order to provide effective strategies for the management of patient rights in Iran, a comparative study was performed on the management of patient rights in places such as the United States, countries in European Union, Canada, England, France, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Africa, and Lithuania. The components and strategies of patient rights in Iran were compared with these countries on the basis of comparative tables. Based on this comparative study and the opinions of the patients about the mechanisms of protection of their rights, a questionnaire was developed. This questionnaire included strategies based on structure, human resources, process, and output. Strategies with this classification were validated by Delphi technique. For this purpose, the questionnaire was sent to 36 connoisseurs, including: Ph.D graduates of hospital management, Ph.D graduates of management of health service, and those with doctorate degrees in law. The scores of this questionnaire were classified as strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5). Average scores were calculated according to the formula: Z = [(X/n) − P0)/√(P0 (1 − P0)/n], P0 ≥ 75%, n = 36, P < 0.05, H1:P0 > 75%, H0:P0 ≤ 75%. If Z computed was over + 1.64 or less than − 1.64, the component of strategy would be approved and it would be considered valid, but if Z was calculated to be between +1.64 and −1.64, the component would be disapproved and it would not be considered valid. In addition, this study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Also, patients had not written their names in the questionnaire.

RESULTS

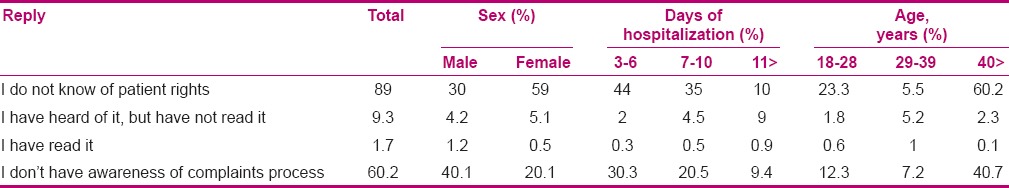

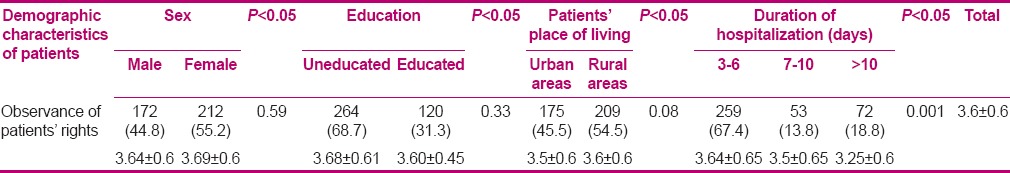

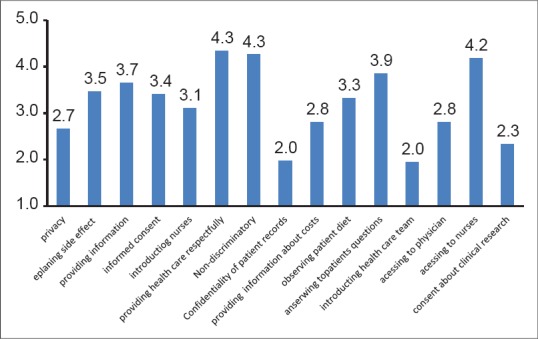

An almost equal number of men and women participated in this study (44.8% and 55.2%, respectively). Overall, 67.4% of the patients had hospital stay duration between 3 and 6 days and most of them were hospitalized in the general surgery ward (12.8%). In these hospitals, 89% of patients were not aware of the relevant hospital legislation and 62.2% were not aware of the complaints process [Table 1]. Overall, observance of patient rights was good (3.6 ± 0.6) [Table 2] and the patients in Tafresh Hospital showed the most satisfaction in this regard (4.1 ± 0.3). The results showed that there was a significant difference between observance of the patient rights according to hospitals, patients’ language, and duration of hospitalization (P = 0.001, P = 0.045, and P = 0.001, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in terms of observance of the patient rights according to sex (P = 0.59), education (P = 0.33), patients’ place of living (P = 0.08), and job (P = 0.9). Hospitals in this study were poor in some of the principles, such as the right of privacy and confidentiality (2.66 ± 2.29), denial of access to medical records except for care providers (1.97 ± 2.17), and providing sufficient information about medical costs and insurance (2.81 ± 1.61) [Figure 1]. On the other hand, the comparative study between patients’ rights in developed and developing countries showed that some rights were not observed in Iran. These rights included the right of copyright of and access to medical records, the right to accept or refuse treatment, the right to accept or reject a meeting, the right to receive treatment at home, the right to access an interpreter, the right to be informed about hospital rules, the right to select other physicians for continuing the treatment, the right to determine the time and place to meet with doctors, and the right to extradite the consent. Finally, this study approved the strategies of patient rights’ management to promote patients’ rights and overcome the weaknesses of laws related to these rights in hospitals in Iran. These included strategies based on structure, human resources, process, and output [Table 3]. Strategies based on structure were the most important strategies to improve the management of patient rights.

Table 1.

Patients’ awareness of the relevant legisla tion in hospitals of Markazi Province, Iran

Table 2.

Patients’ satisfaction with respect to their rights based on demographic characteristics in hospitals of Markazi Province, Iran

Figure 1.

Comparison of patients’ rights in the hospitals in central province of Iran

Table 3.

Strategies approved of patient rights management by Delphi technique in Iran

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that despite the introduction of specific legislation, hospital patients are not yet aware of their legal rights, as 9 out of 10 patients were not aware of the relevant hospital legislation and 4 out of 10 patients were not aware of the complaints process, which is consistent with the findings of other similar studies.[33,34] It has been suggested that patients must be informed about their rights during their hospital admission as an effective strategy for respecting patients’ rights.[11] Among the health professionals, it is accepted that the greatest responsibility for preserving patients’ rights lies with physicians, midwives, and nurses.[4] This task can be undertaken by the nursing staff as they are usually in closer contact with patients compared to other healthcare workers, and thus are the most suitable supporters of the patients’ rights.[35] To date, nurses have not undertaken this role in Iran because there is a lack of nursing personnel and time, which stems from unsuitable organization of the manpower in hospitals. This is consistent with the findings of other similar studies.[11]

Overall, patients were not satisfied with the observance of their privacy and confidentiality. The concept of privacy is used in many disciplines and is recognized as one of the important concepts in nursing as well.[17,36] In fact, the terms “privacy and confidentiality of the person” and “dignity” are interrelated. On the other hand, this issue builds trust in the patient-physician relationship. Kleinman has shown that physicians should consider patients’ information as professional secrets.[37] The consequences of violating this law will increase the stress and aggressive behaviors in patients.[38,39] It is consistent with the findings of other similar studies.[40]

In our study, there was no “denial of access to medical records except for the care providers,” whereas all information about the patient's health status, medical condition, diagnosis, and all other personal information must be kept confidential, even after the patient's death. Mechanicn[41] and Kilpia[42] showed that patients who are not reassured and lack trust require constant alertness and they are in a state of anxiety. It seems that in Iran, absence of electronic health records (EHR) is a barrier to the establishment of patients’ rights in hospital structure. On the other hand, in this study, three out of five patients stated that they were not fully informed about clinical research. Consent forms are the principal method for obtaining informed consent from biomedical research participants. Reicken[43] showed that all protocols must be submitted to proper ethical review procedures, and Ezekie[44] believed that informed consent makes clinical research ethical. Altavilla[45] showed that many differences exist in the protection of children enrolled in clinical trials. Such differences are especially due to a lack of public awareness on ethical issues in this field.

It also seems that in Iran, a lack of binding rules, knowledge of the law, education, and punitive policies can undermine these rights. This finding is consistent with the findings of other similar studies.[46] In the present study, the patients responded that they did not know the healthcare provision team. However, attention to this right reinforces the physician–patient interactions and maintains patients’ freedom in clinical decision making. This could be the result of various factors such as complexity and dispersion in hospital structure and a lack of time. These findings are seemingly consistent with similar studies conducted in this area.[25]

In our survey, most of the patients were satisfied with respectful provision of healthcare. This could be the result of effective communication. In fact, having good communication skills is essential for doctors to establish good physician–patient relationship.[47] Vally showed effective communication with patients has a desirable impact on treatment, recovery, and final outcome.[48] In this study, most of these patients were satisfied with provision of sufficient information about their disease (73%) and explanation of common risks and side effects (69.2%). Patients have the right to be fully informed about their condition; the proposed medical procedures together with the potential risks and benefits of each procedure; alternatives to the proposed procedures, including the effect of non-treatment; and about the diagnosis, prognosis, and progress of treatment. Rogers[49] showed that respect for patient autonomy is a fundamental principle of medical ethics, demonstrated in practice by facilitating patient choice. As Beckman[50] reported, information is a very important issue for patients, given that it constitutes one of the major indicators of their satisfaction as well as a reason for legal proceedings. Shared decision making is associated with patient satisfaction. Studies have shown that most patients prefer to be involved in decision making, although their preferences vary.[23] Patients’ participation in decision making and preservation of their rights cause improvement in treatment, shorter hospitalization period, reduced treatment costs, and prevention of irreparable physical and emotional damages.[51] In this study, this could be attributed to various factors such as having an effective communication or informing the patients about their disease, which is not consistent with the findings of other similar studies,[22,52] though the findings of this study are in line with the findings of other studies.[11,53]

Moreover, about half of the patients were satisfied with informed consent (53.8%). This could be due to the protection of doctors against potential shortcomings. As Dawes[54] reported, informed consent is an important aspect of surgery. Yet, there has been little inquiry as to what patients want to know before their operation. Also, the government has a responsibility to ensure a healthy social and economic environment and provide the structures and mechanisms to guarantee equal access to affordable healthcare, with special regard to the more vulnerable groups of the population. As Black[55] has stated, healthcare policies must be justly since they ensure healthcare ethics.

The patients assessed equitable access to healthcare service as good, which is consistent with the findings of other corresponding studies.[33] In our survey, there was quick access to nurses, but the patients did not have access to their doctors in the hospitals. In fact, everyone has the right to receive healthcare quickly. Overall, it seems that due to their administrative and educational duties and the need for doctors in the operating room or in the ambulatory care visit, there is a lack of access to doctors. This finding is in line with other findings reported in Iranian studies.[27] The limitation of this study was the lack of time for implementation of these strategies and studying their impact on the promotion of patients’ rights in the hospital under study.

CONCLUSION

The results suggest that the establishment of a framework for application of effective strategies can help to promote professional ethics, encourage board-based agreements related to ethical decisions, reduce ethical conflicts, and increase implementation of law on patients’ rights. Moreover, the PBR of Iran is in need of further revision and modification, and extensive education should be provided for the patients and the healthcare professionals as this is the most important structural strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all patients who participated in the study and the hospital managers for facilitating this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Grant from Arak University of Medical Sciences Research Committee (contract No.: 91.07.01.401)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbasi S, Ferdosi M. Do electronic health records standards help implementing patient bill of rights in hospitals. Acta Inform Med. 2013;21:20–2. doi: 10.5455/AIM.2012.21.20-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydin E. Rights of patients in developing countries: The case of Turkey. J Med Ethics. 2003;30:555–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purtilo R. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Company; 1999. Etical dimension in health professions; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakan Ozdemir M, Ozgür Can I, Ergönen AT, Hilal A, Onder M, Meral D. Midwives and nurses awareness of patients’ rights. Midwifery. 2009;25:756–5. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallberg LH. Patients’ rights in Europe: Where do we stand and where do we go? Eur J Health. 2000;7:1–3. doi: 10.1163/15718090020523007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillon R. An introduction to philosophical medical ethics: The Arthur case. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1117–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6475.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zere E, Mandlhate C, Mbeeli T, Shangula K, Mutriua K, Kapenambili W. Equity in health care in Namibia: Developing a needs-based resource allocation formula using principal components analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2007;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delph YM. Health priorities in developing countries. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;1:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almond P. What is consumerism and has it had an impact on health visiting provision? A literature review. Adv Nurs J. 2001;35:893–901. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox J. Consumerism: The different perspectives with health care. Br Nurs J. 2003;12:321–6. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2003.12.5.11178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merakou K, Dalla-Vorgia P, Garanis-Papadatos T, Kourea-Kremastinou J. Satisfying patients’ rights: A hospital patient survey. J Nurs Ethics. 2001;8:499–509. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzu N, Ergin A, Zencir M. Patients’ awareness of their rights in a developing country. Public Health. 2006;120:290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Report of patient rights. Chicago, Illinois and Washington, D.C: American Hospital Association, AHA Board; 1973. AHA. A patients’ bill of rights. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozdemir MH, Ergonen TA, Sonmez E, Can IO, Salacin S. The approach taken by physicians working at educational hospitals in Izmir towards patients rights. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joos SK, Hickam DH, Gordon GH, Baker LH. Effects of a physician communication intervention on patient care outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:147–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan D, Goh LG. The doctor patient relationship: A survey of attitudes and practices of doctors in Singapore. Bioethics. 1998;14:58–76. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyal L. Human need and the right of patients to privacy. J Contemp Health Law Policy. 1997;14:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra S, Waitzkin H. Physician- Patient Communication. West J Med. 1987;147:328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labarere J, Francois P, Auquier P, Robert C, Fourny M. Development of a French inpatient satisfaction questionnaire. Int J Quality Health Care. 2001;13:99–108. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lledó R, Salas L, González M, Rodríguez T, Sánchez M, Ranz M, et al. The rights of the hospital patient: The knowledge and perception of their fulfillment on the part of the professional. The Group in Catalonia of the Spanish Society of Care for the Health Services User. Rev Clin Esp. 1998;198:730–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulter A, Cleary PD. Patients’ Experiences with hospital care in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:244–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsen B, Aakvik A. Patient involvement in clinical decision making: The effect of GP attitude on patient satisfaction. Health Expect. 2006;9:148–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghodsi Z, Hojjatoleslami S. Knowledge of students about Patient Rights and its relationship with some factors in Iran. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;31:345–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joolaee S, Tschudin V, Nikbakht AR, Nasrabadi Z, Yekta P. Factors affecting patients right practice: The lived experiences of Iranian nurses and physicians. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;550:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joolaee S, Nikbakht Nasrabadi AR, Parsa Yekta Z, Tschudin V, Mansouri I. An Iranian perspective on patients’ right. J Nurs Ethics. 2006;13:488–502. doi: 10.1191/0969733006nej895oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsapoor A, Mohhammad K, Malek Afshar M, Ala eddini F, Larijani B. Observance of patients rights: A survey on the views of patients, nurses and physician. Iran Med Ethics Hist Med J. 2010;3:53–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaskooei Eshkevari K, Karimi M, Asnaashari H, Kohan N. The Assessment of observing patients’ rights in Tehran University of Medical Sciences hospitals. Iran J Med Ethics His Med J. 2009;2:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leuter C, Petrucci C, Mattei A, Tabassi G, Ioreto LL. Ethical difficulties in nursing, educational needs and attitudes about using ethics resources. Nurs Ethics J. 2012;20:348–58. doi: 10.1177/0969733012455565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yakov G, Shilo Y, Tzippy S. Nurses’ perceptions of ethical issues related to patients’ rights law. J Nurs Ethics. 2010;17:501–10. doi: 10.1177/0969733010368199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.León Correa FJ. From clinical to social bioethics in Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2008;136:1078–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rashidyan A. Tehran: Policy Development in Health System; 2009. Clinical governance in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzu N, Ergin A, Zencir M. Patients’ awareness of their rights in developing countries. Public Health. 2001;120:290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zülfikar F, Ulusoy MF. Are Patients Aware of Their Rights? A Turkish study. Nurs Ethics. 2001;8:487–98. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes P. The patients’ friend. Nurs Times. 1991;87:16–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman I. Privacy: A concept analysis. Environ Behav. 1976;8:7–29. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleinman I, Baylis F, Rodgers S, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: Confidentiality. CMAJ. 1997;156:521–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schopp A, Leeino Kilpi H, Valimaki M, Dassen T, Gasull M, Lemonidou C, et al. Perceptions of privacy in the care of elderly people in five European countries. Nurs Ethics. 2003;10:39–47. doi: 10.1191/0969733003ne573oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amini A, Tabrizi JS, Shaghaghi A, Narimani MR. The status of observing patient rights charter in outpatient clinics of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences: Perspectives of health service clients. Iran J Med Educ. 2013;13:611–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woogara J. Patients’ privacy of the person and human rights. Nurs Ethics May. 2005;12:273–87. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne789oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. J Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:657–68. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leino-Kilpi H, Välimäki M, Dassen T, Gasull M, Lemonidou C, Scott A, et al. Privacy: A review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:663–71. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reicken HW, Ravich R. Informed consent to biomedical research in Veterans administration hospitals. JAMA. 1982;248:344–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000;283:2701–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altavilla A, Giaquinto C, Giocanti D, Manfredi C, Aboulker JP, Bartoloni F, et al. Activity of ethics committees in Europe on issues related to clinical trials in paediatrics: Results of a survey. J Pharmaceuticals Policy Law. 2009;11:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;24:1772–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trumble C. Communication skills training for doctors increase patient satisfaction. Clinical Governance J. 2006;4:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valley T. London: University of Western antario; 2003. Effective physicians-patient communication and health outcome: A review article; pp. 79–133. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogers WA. Are guidelines ethical? Some considerations for general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:663–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor – patient relationship and malpractice: Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hojjatoleslami S, Ghodsi Z. Respect the rights of patient in terms of hospitalized clients: A cross sectional survey in Iran. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;31:464–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waitzkin H. Doctor- patient communication: Clinical implications of social scientific research. JAMA. 1984;252:2441–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.17.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leino Kilpi H, Kurittu K. Patients’ rights in hospital: An empirical investigation in Finland. Nurs Ethics J. 1995;2:103–13. doi: 10.1177/096973309500200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dawes PJ, Davison P. Informed consent: What do patients want to know? J R Soc Med. 1994;87:149–52. doi: 10.1177/014107689408700312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Black M, Mooney G. Equity in health care from a communication standpoint. Health Care Anal J. 2002;10:193–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1016583100955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]