Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study was to compare changes in pain, oxygenation, and ventilation following endotracheal suctioning with open and closed suctioning systems in post coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) patients.

Materials and Methods:

130 post CABG mechanically ventilated patients were randomly allocated to undergo either open (n = 75) or closed (n = 55) endotracheal suctioning for 15 s. The patients received 100% oxygen for 1 min before and after suctioning. Pain score using critical-care pain objective tool (CPOT) was compared during suctioning between the two groups. Arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2), PaO2 to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) (PF) ratio, and arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) were compared at baseline and 5 min after suctioning. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) was compared at baseline, during suctioning, and at 1 min interval after suctioning for 5 min between the two groups.

Results:

The patients were the same with regard to CPOT scores, i.e. 3.21 (1.89) and 2.94 (1.56) in the open and closed suctioning systems, respectively. SpO2 did not change significantly between the two groups. Changes in PaO2 and PF ratio was more significant in the open than in the closed system (P = 0.007). Patients in the open group had a higher PaCO2 than those in the closed group, i.e. 40.54 (6.56) versus 38.02 (6.10), and the P value was 0.027.

Conclusions:

Our study revealed that patients’ pain and SpO2 changes are similar following endotracheal suctioning in both suctioning systems. However, oxygenation and ventilation are better preserved with closed suctioning system.

Keywords: Closed suctioning, coronary artery bypass grafting, endotracheal suctioning, open suctioning, oxygenation, pain, ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is an efficacious technique of treating coronary artery stenosis.[1,2,3,4,5] To carry out cardiovascular surgeries, patients must be anesthetized and intubated that requires mechanical ventilation support.[6] Following the surgery, for monitoring of hemodynamic indices, adequate volume therapy, and treatment with positive inotropic agents and vasopressor drugs, patients are taken to the intensive care unit (ICU).[7] Tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation significantly impair airway secretion clearing; due to inability to clear their airways spontaneously, the intubated patient needs intermittent suctioning of secretions.[8,9] Basically, tracheal suctioning is used for removing secretions from airways in intubated patients under mechanical ventilation in the ICU.[10,11] Suctioning is, therefore, warranted in mechanically ventilated patients both to prevent airway obstruction and to decrease the work of breathing caused by retrained secretions. Nevertheless, this maneuver is potentially harmful and may lead to critical and life-threatening complications.[12] Endotracheal suction is associated with some complications and risks including bleeding, infection, atelectasis, hypoxemia, cardiovascular instability, elevated intracranial pressure, and lesions in the tracheal mucosa as well. The procedure has been described painful and uncomfortable by patients,[13,14] as it increases the workload of the heart and oxygen consumption that may be associated with serious postoperative complications, especially in post CABG patients.[15] The most commonly reported complication is arterial hypoxemia, while atelectasis, bronchospasm, tracheal mucosal damage, cardiac arrhythmia, intracranial hypertension, and even cardiac arrest have been reported.[10,12]

Two standard methods for clearing endotracheal secretions are available: The open and closed suctioning systems. For removing secretions of patient's airway, the open suction technique is performed by disconnecting the ventilator circuit from the patient's endotracheal tube to insert the sterilized suction catheter through it. Closed suctioning system is performed by positioning a catheter between the endotracheal tube and the Y piece of the ventilator circuit and the patient does not get disconnected from the ventilator.[9,12,16] Closed suctioning was originally introduced for hygienic reasons and as a method of avoiding desaturation[17,18,19] and reduction in lung volume loss during suctioning.[9,20]

Both systems have been compared by different studies with regard to physiologic disturbances, oxygenation, and ventilation changes. Results of most of the studies favored closed suctioning system; nevertheless, there were rather small differences between these two systems and were clinically not relevant.[10] The advantages of these two systems and which system should be preferred, however, have not been substantiated and little is known about the effectiveness of these two suction methods on the respiratory parameters of CABG patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. However, the impact of closed suctioning system on pain has not been investigated in mechanically ventilated patients. The objective of this study was to compare endotracheal suctioning with open and closed systems in post CABG patients under mechanical ventilation. The primary outcome was to compare pain using critical-care pain objective tool (CPOT) scale between the groups. The secondary outcomes included comparison of SpO2, PaO2, PF ratio, and PaCO2 between the two groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a single-blind parallel clinical trial which was performed on post CABG patients undergoing mechanical ventilation admitted in cardiac surgery ICU of Emam Reza hospital of Mashhad in 2013. After obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences and written informed consent from the subjects or, when incompetent, from their next of kin, 130 adult patients (>18 years) under mechanical ventilation requiring endotracheal suctioning following CABG, with Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) score of − 1 or 0 were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were: History of lung disease; presence of thick secretions requiring mucolytics; positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) >5 cm H2O; PF ratio <200; presence of dysrhythmia; hemodynamic instability (mean arterial pressure <70 mmHg), requiring administration of vasopressors or inotropes.[12,21,22] The patients were randomly divided into open and closed suctioning system groups using random number table.

All patients received 100% oxygen for 1 min before and after suctioning. They were ventilated with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) with tidal volumes of 8 ml/kg, frequency of 10–12 breaths per minute (to maintain PaCO2 35–45 mm Hg, FiO2 40–60%, and PEEP 5 cm H2O).

Endotracheal suctioning was performed for 15 s on a protocol base by trained ICU nurses. In the open group, the endotracheal tube was disconnected from the ventilator. A 14-Fr sized disposable suction catheter was passed down in the endotracheal tube and advanced until resistance was met and withdrawn 0.5 cm.[10,12] In all the patients, a negative pressure of 150–200 mm Hg[12] was then applied with both systems continuously for 15 s and the catheter withdrawn while rotating slightly. The patient was then immediately reconnected to the ventilator circuit.[10]

Patients in the closed group were connected to a commercially available closed system (TY-CARE) provided with a 14-Fr sized suction catheter. It was placed between the endotracheal tube and the Y piece of the ventilator's circuit. The suction catheter was in the locked position and the water irrigation port was kept closed all the time. Then for suctioning, it was unlocked and inserted into the endotracheal tube via the Y-piece connector, applying continuous suction for 15 s as the catheter was slowly withdrawn. The procedure was performed identically for all the patients.

Pain using the CPOT was recorded at baseline and during suctioning. Patients received analgesic according to the unit analgesic protocol as necessary only after the procedure, because the time was too short to administer analgesic simultaneously. PaO2, PF ratio, and PaCO2 were compared at baseline and 5 min after suctioning. SpO2 was recorded at baseline, immediately after, and every minute for 5 min after suctioning. CPOT, PaO2, PF ratio, and PaCO2 were compared between and within groups. Arterial blood oxygen saturation was assessed continuously by pulse oximetry, using standard ICU equipment. Arterial blood gases were measured from an indwelling arterial line by a GEM Premier 2000 gas analyzer.

SPSS version 16.0 was used for data entry and statistical analyses. The data were tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test which revealed normal distribution of the data. Normally distributed data were analyzed by t-test; otherwise, nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used. χ2 test was used for analysis of dichotomous variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

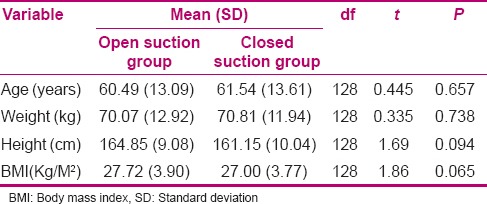

Demographic data of the patients enrolled in the study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and physical characteristics of the two groups of patients enrolled in the study

One hundred and thirty patients, 79 male (60.7%) and 51 female (39.2%), were studied. All patients completed the study. Based on the results obtained through Chi-square test, no significant statistical differences were observed between the two groups of closed and open suctioning systems with respect to demographic specifications (sex, age, weight, height, body mass index) (P > 0.05). The mean age of the participants was 61.01 (13.35) years. Most of the participants were male (60.7%).

CPOT was zero before suctioning in both groups. During suctioning, the CPOT increased to 3.21 (1.89) and 2.94 (1.56) in the open and closed systems, respectively (P = 0.46).

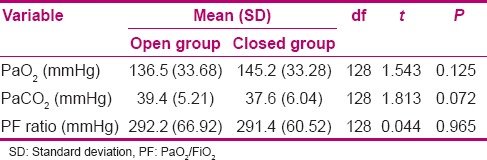

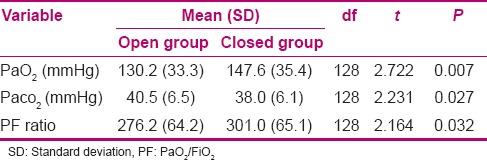

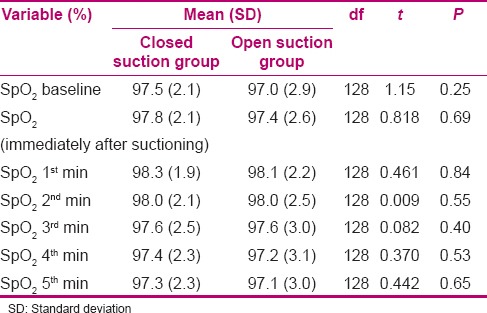

SpO2, PaO2, PF ratio, and PaCO2 were similar before suctioning in both groups [Table 2]. However, patients in the closed group had a significantly higher PaO2 and PF ratio compared to the open group, 5 min after suctioning [Table 3]. Both groups showed a slight increase in PaCO2 after suctioning. However, it was more significant in the open group [Table 3]. SpO2 was slightly higher in the closed group than in the open group, with no statistically significant difference [Table 4].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean respiratory parameters between the two groups at baseline (before suctioning)

Table 3.

Comparison of mean respiratory parameters between the two groups 5 min after suctioning

Table 4.

Comparison of mean arterial oxygen saturation between the two groups at different time periods

No patients showed bronchospasm or dysrhythmias during suctioning.

DISCUSSION

We found that endotracheal suctioning using a closed system can better preserve oxygenation and ventilation in comparison with the conventional open system. On the other hand, both systems are similar with regard to pain following suctioning.

During suctioning with closed suctioning system, mechanical ventilation support is continuous and this would maintain PEEP with minimal changes in FiO2.[9,23] This avoids lung volume loss, with fewer changes occurring in oxygenation and ventilation during suctioning.[9,16,19,20,23,24] Our findings were similar to these reports indicating better oxygen saturation with closed system. However, this benefit was not clinically significant because the effect was transient and both groups returned to pre-suction values after a few minutes. This may be due to application of 100% oxygen before suctioning, as recommended for routine suctioning.

Like our study results, Jongerden et al. showed that there was a mild change in SpO2 with closed suctioning.[10] In another study, Fernandez et al. concluded that open system induces remarkable losses in lung volume that could be decreased by applying closed system; they did not observe significant arterial oxygen desaturation.[12] In both studies, the authors did not evaluate PaO2 changes in their research. There might be a significant change with PaO2, but a mild change in SpO2 because of the difference regarding the value range.

On the other hand, application of closed system can be more beneficial in cases where the patients are oxygen dependent or require high levels of PEEP, since separation of patients from mechanical ventilation during open suctioning even for a short time can lead to patients’ desaturation.

In contrast, Corley et al. questioned the benefits of closed suctioning.[20] Although they showed less lung volume loss with the closed system, it was associated with slower recovery of end expiratory lung volume due to changes in lung impedance.

Another study showed that there was a significant difference in arterial oxygen pressure, which indicated better results of closed suction in comparison with the open method. A significant 18% decrease in arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) induced by open endotracheal suction system and a remarkable increase in PaO2 were observed after suctioning by the closed system.[24]

Moreover, other studies showed that ventilation interruption, decrease in dynamic compliance, loss of positive airway pressure, and reduction in lung volume lead to hypoxemia during open suctioning system.[9,12,21,25,26] These effects of open suctioning system on oxygenation were similar those observed in our study.

Endotracheal suctioning can affect ventilation as well as oxygenation during mechanical ventilation. Our study showed that both systems resulted in an increase in PaCO2 following suctioning; nevertheless, PaCO2 was significantly higher in the open group. This is due to lack of disconnection from the ventilator and continuation of mechanical ventilation in the closed group. However, these changes were not clinically significant because the procedure is quite short and the baseline PaCO2 was not high. This can be of clinical significance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients and in those with impaired initial ventilation.

The main cause of more cardiorespiratory stability in closed suctioning compared with open suctioning is that closed suctioning is intended to preserve ventilation and FiO2 during suctioning.[9,26]

Lasocki et al. measured arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) in their study. They were able to demonstrate a rise in PaCO2 using open suctioning system as compared with baseline values. No significant changes in PaCO2 were observed at the different times of the closed suctioning system.[24]

In addition, another study showed that PaCO2 after open suctioning showed a significant increase, in comparison with the closed method.[9]

Tracheal suctioning has been reported as a painful experience by acutely and critically ill patients.[27,28,29] Nevertheless, there is no report comparing the impact of closed versus open systems on pain during suctioning. To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing pain following endotracheal suctioning with open and closed suctioning systems. In this study, we compared the pain status during open and closed suctioning using CPOT in ventilated post CABG patients. We found that both procedures were painful with no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.464). Although it seems that insertion of catheter for suctioning with closed system might be gentler and, hence, less painful, our research did not prove it.

In addition to its beneficial effects on ventilation and oxygenation, the closed system might decrease the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) as reported by David et al.[30] We did not investigate the VAP incidence in our study because all our patients got extubated before 8 h and use of the closed system for this purpose is recommended for those under mechanical ventilation for more than 4 days.

Our study had some limitations. First, patients with underlying respiratory diseases or requiring high levels of PEEP were excluded. Therefore, our results cannot be extrapolated to these populations. Second, all patients received 100% oxygen before suctioning which might mask the true impact of suctioning with either systems on oxygenation and ventilation.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, we could show that endotracheal suctioning with open system affects oxygenation more significantly compared with the closed system. On the other hand, both systems are similar with respect to pain. However, these effects are not clinically relevant, since in both techniques the pressure and force applied to the trachea are similar. However, the hemodynamic fluctuations were quite short and returned to pre-procedural values after a few minutes. Furthermore, these did not affect the patients’ outcome with regard to new cardiovascular events, time of mechanical ventilation, or ICU stay.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Gonabad University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: Nill.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Morice MC, Banning AP, Serruys PW, Mohr FW, et al. Treatment of complex coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes: 5-year results comparing outcomes of bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention in the SYNTAX trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:1006–13. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mir Mohammad-Sadeghi M, Naghiloo A, Najarzadegan MR. Evaluating the relative frequency and predicting factors of acute renal failure following coronary artery bypass grafting. ARYA Atheroscler. 2013;9:287–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackledge HM, Squire IB. Improving long-term outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary revascularisation: Results from a large, population-based cohort with first intervention 1995-2004. Heart. 2009;95:304–11. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Domburg RT, Kappetein AP, Bogers AJ. The clinical outcome after coronary bypass surgery: A 30-year follow-up study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:453–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst-Rodrigues MV, Carvalho VO, Auler JOC, Jr, Feltrim MIZ. PEEP-ZEEP technique: Cardiorespiratory repercussions in mechanically ventilated patients submitted to a coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:108. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carl M, Alms A, Braun J, Dongas A, Erb J, Goetz A, et al. S3 guidelines for intensive care in cardiac surgery patients: Hemodynamic monitoring and cardiocirculary system. Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:12. doi: 10.3205/000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada N. Closed suctioning system: Critical analysis for its use. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2010;7:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cereda M, Villa F, Colombo E, Greco G, Nactoi M, Pesenti A. Closed system endotracheal suctioning maintains lung volume during volume controlled mechanical ventilation. Intensive care Med. 2001;27:648–54. doi: 10.1007/s001340100897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jongerden IP, Kesecioglu J, Speelberg B, Buiting AG, Leverstein-van Hall MA, Bonten MJ. Changes in heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and oxygen saturation after open and closed endotracheal suctioning: A prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:647–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst-Rodrigues MV, Carvalho VO, Auler JO, Jr, Feltrim MI. PEEP-ZEEP technique: Cardiorespiratory repercussions in mechanically ventilated patients submitted to a coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:108. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez MD, Piacentini E, Blanch L, Fernandez R. Changes in lung volume with three systems of endotracheal suctioning with and without preoxgynation in patients with mild-to-moderate lung failure. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2210–5. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen CM, Rosendahl-Nielsen M, Hiermind J, Egerold I. Endoteracheal suctioning of the adult intubated patient-what is the evidence? Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2009;25:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arroyo-Novoaa CM, Figueroa-Ramosa MI, Puntillo KA, Stanik-Huttb J, Thompsonc CL, White C, et al. Pain related to tracheal suctioning in awake acutely and critically ill adults: A descriptive study. Intensive Critical Care Nurs. 2008;24:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AbuRuz ME, Alaloul F. Patients’ Pain experience after Coronary artery bypass graft Surgery. J Am Sci. 2013;9:592–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozden D, Görgülü RS. Effects of open and closed suction systems on the haemodynamic parameters in cardiac surgery patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2014 doi: 10.1111/nicc.12094. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee EY, Kim SH. Effects of open or closed suctioning on lung dynamics and hypoxemia in mechanically ventilated patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2014;44:149–58. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2014.44.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hough JL, Shearman AD, Liley H, Grant CA, Schibler A. Lung recruitment and endotracheal suction in ventilated preterm infants measured with electrical impedance tomography. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jpc.12661. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans J, Syddall S, Butt W, Kinney S. Comparison of open and closed suction on safety, efficacy and nursing time in a paediatric intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care. 2014;27:70–4. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corley A, Spooner AJ, Barnett AG, Caruana LR, Hammond NE, Fraser JF. End-expiratory lung volume recovers more slowly after closed endotracheal suctioning than after open suctioning: A randomized crossover study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:742. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briassoulis G, Briassoulis P, Michaeloudi E, Fitrolaki DM, Spanaki AM, Briassouli E. The effects of endotracheal suctioning on the accuracy of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production measurements and pulmonary mechanics calculated by a compact metabolic monitor. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:873–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b018ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David D, Samuel P, David T, Keshava SN, Irodi A, Peter JV. An open-labelled randomized controlled trial comparing costs and clinical outcomes of open endotracheal suctioning with closed endotracheal suctioning in mechanically ventilated patients medical intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2011;26:482–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer E, Schuhmacher M, Ebner W, Dettenkofer M. Experimental contamination of a closed endotracheal suction system: 24 h vs 72 h. Infection. 2009;37:49–51. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-7444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lasocki S, Lu Q, Sartorius A, Fouillat D, Remerand F, Rouby JJ. Open and closed-circuit endotracheal suctioning in acute lung injury: Efficiency and effects on gas exchange. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirr SM, Lange M, Hartmann C, Bohnhorst B, Peter C. Closed versus open endotracheal suctioning in extremely low-birth-weight neonates: A randomized, crossover trial. Neonatology. 2013;103:124–30. doi: 10.1159/000343472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazdannik AR, Haghighat S, Saghaei M, Eghbali M. Comparing two levels of closed system suction pressure in ICU patients: Evaluating the relative safety of higher values of suction pressure. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:117–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arroyo-Novoa CM, Figueroa-Ramos MI, Puntillo KA, Stanik-Hutt J, Thompson CL, White C, et al. Pain related to tracheal suctioning in awake acutely and critically ill adults: A descriptive study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arif-Rahu M, Grap MJ. Facial expression and pain in the critically ill non-communicative patient: State of science review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26:343–52. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadian ZS, Sabet RS. The effect of endotracheal tube suctioning education of nurses on decreasing pain in premature neonates. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:340–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.David D, Samuel P, David T, Keshava SN, Irodi A, Peter JV. An open-labelled randomized controlled trial comparing costs and clinical outcomes of open endotracheal suctioning with closed endotracheal suctioning in mechanically ventilated medical intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2011;26:482–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]