Abstract

Background:

Natural delivery is distressing and the mother's severe pain and anxiety in this condition can have negative impacts on the fetus, mother, and the delivery process. Yet, pain and anxiety can be reduced by supporting the mother by a doula. Thus, the present study aims to compare the effects of doula supportive care and acupressure at the BL32 point on the mother's anxiety level and delivery outcome.

Materials and Methods:

The present clinical trial was conducted on 150 pregnant women who had referred to the Shoushtari Hospital, Shiraz, Iran for delivery in 2012. The subjects were randomly divided into two intervention groups (supportive care and acupressure) and a control group (hospital routine care). The mothers’ anxiety score was assessed before and after the intervention, using the Spielberger questionnaire. The delivery outcomes were evaluated, as well. Subsequently, the data were entered into the SPSS statistical software (Ver. 16) and analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA), Chi-square test, correlation coefficient, and logistic regression analysis.

Results:

After the intervention, the highest and lowest mean scores of the state and trait anxieties were compared with the control and the supportive care groups, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). A significant relationship was found between the labor length and mother's anxiety score after the intervention in the supportive care (P <</i> 0.001) and the control group (P = 0.006). However, this relationship was not significant in the acupressure group (P = 0.425). Also, a significant difference was observed among the three groups regarding the mothers’ anxiety level (P = 0.009).

Conclusions:

The study results showed that doula supportive care and acupressure at the BL32 point reduced the mother's anxiety as well as the labor length. Therefore, non-pharmacological methods are recommended to be used during labor for improving birth outcomes and creating a positive birth experience.

Keywords: Acupuncture points, anxiety, childbirth, doula, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Childbirth has a severe psychological, social, and emotional impact on both the mother and her family. Childbirth is in fact one of the major phenomena a woman experiences in her life. Therefore, a negative experience of childbirth can have negative impacts on both the woman and her family.[1] Delivery anxiety is related to the mother's worry and fear about pregnancy, the neuroendocrine changes during pregnancy, and predictions about the birth outcome. In general, anxiety refers to distress that might occur in response to stress.[2] Korukcu conducted a study in Turkey in order to investigate the relationship between fear of delivery and anxiety levels. In that study, 49.4% of the nulliparous women and 50.6% of the multiparous ones were afraid of delivery and a significant relationship was found between fear and anxiety.[3] Fear and anxiety resulting from delivery pain increased the mother's pain and discomfort during the delivery process.[4] Thus, interventions are required to be conducted in order to decrease the negative effects of the maternal physiological processes that occur due to the mother's pain and anxiety and lead to maternal and fetal damage.[5]

Supporting a woman in labor is an old concept that has been investigated by the anthropologists in 150 various cultures. Such women were usually supported by a family member, friend, or a woman during labor.[6] The support is most effective in case it is started at the beginning of the labor and the supporter does not work in the service providing institute. For example, a doula can be of great help in supporting a woman in labor. The doula's support includes emotional support (continuous presence, reassurance, encouragement, and admiration), physical support (reduction of thirst, hunger, and pain), providing information about the delivery process and how to cope with it, respecting the woman's decision, and helping her create relationships with other caregivers.[7]

By calming the woman and suggesting various positions during the labor, the doula increases the fetus’ descent. Besides, continuously supporting the mother leads to reduction of labor length, less utilization of oxytocin for augmentation, a lower rate of instrumental delivery, less utilization of epidural anesthesia and narcotics, and a lower rate of the Cesarean section.[8] In addition to the mother's movements, the doula also recommends special positions that enhance the labor progress and improve the maternal problems, such as backache and inappropriate uterine contractions.[5] Pelvic dimensions tend to change because of the mother's movements; thus, the mother's movements help the fetus rotation and descent and sedate the pain related to inappropriate positions or long-term labor.[9] In the study by Kennel et al., (1991), continuous support by a doula reduced the labor length by one to two hours, increased the mother's capability for controlling the labor, shaped a positive delivery experience, and increased the mother's breast feeding ability during the first month after birth.[10]

Acupressure is another non-pharmacological method for decreasing pain and anxiety. Acupressure is a type of massage therapy developed in ancient China. It is similar in nature to acupuncture and is a non-invasive method. Acupressure stimulates the body for production of endorphin and opioid, and consequently, reduces the pain. Relaxation by stimulation of the acupressure point increases the feeling of good health and reduces muscle fatigue.[11] Chao (2007) and Chung (2003) emphasized the effectiveness of acupressure in reducing labor pain.[12,13] Agarwal et al., (2005) also reported that acupressure at some special points could reduce anxiety.[14]

As helping two vulnerable groups of the society; that is, mothers and children, are the main priorities in the health and treatment system, sedating the mothers’ pain and reducing their anxiety during labor are of utmost importance.[15] Therefore, the present study aims to compare the effects of doula supportive care and acupressure at the BL32 point on the mother's anxiety level and delivery outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized clinical trial was conducted in the delivery ward of the selected educational center of the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Shoushtari Hospital), in 2012. Taking into consideration, d = 5, α = 0.05, 1-β =0.90, SD = 7, and the following formula, a 150-subject sample size (50 subjects in each group) was determined for the study:

The subjects were selected through simple random sampling and were divided into supportive care, acupressure, and control groups, using stratified block randomization. In doing so, a number was randomly selected from the table of random numbers and the researcher moved toward the right or left column or row and wrote the five-digit numbers down. As the participants were divided into three groups in this study, the three-therapy method was used and classification was performed as follows: A: Supportive care group, B: Acupressure group, and C: Control group. Accordingly, ABC: 1, ACB: 2, BAC: 3, BCA: 4, CAB: 5, and CBA: 6. It should be noted that numbers 0, 7, and 9 were ignored.

The inclusion criteria of the study were, a gestational age of 37–41 weeks based on the date of the last menstrual cycle or first and second trimester ultrasound, first or second pregnancy, being between 18 and 35 years old, single pregnancy, head presentation, lack of obvious chromosomal abnormalities and fetal anomalies, not using any special drugs during pregnancy, and having at least middle school education. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria of the study were maternal diabetes, growth restriction, Rhesus (RH) incompatibility, history of smoking, history of tobacco use, pre-eclampsia, oligohydramnios, placenta previa, placental abruption, thick meconium, suffering from any physical or mental disorder, and receiving any kind of medication, including, pethidine, hyoscine, oxytocin, and atropine.

The demographic information questionnaire was completed by the researcher through interviewing the mothers. In addition, the Spielberger questionnaire was used in order to assess the anxiety level. This questionnaire included 40 questions in two 20-item scales. The first 20 questions measured the state anxiety, which was defined as a feeling of worry and tension resulting from situational stress. The second 20 questions assessed the trait anxiety, which referred to individual differences in the tendency toward evaluating the situations as threatening or dangerous.[16] In Iran, Aghamohammadi et al., (2007) used this questionnaire on 150 patients undergoing surgery and reported its reliability as 97%, which was the basis for the present study.[17] The supportive care and acupressure groups completed this questionnaire before (the start of the active phase of labor) and after (at the end of the first stage) the intervention. In the control group, the questionnaire was completed at the beginning of the active phase of the labor and at the end of the first stage.

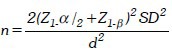

In the first group, the researcher was beside the mother from her entrance into the department, calmed and encouraged her, and recommended appropriate positions to the mother based on the labor stages. In 3–8 cm dilatation, the mother was placed at activity positions, such as lunge, tailor stretching, leaning, and straddle a chair, for 20 minutes, and at relaxing positions, such as semi-setting and side-lying, for 10 minutes. At the 8–10 cm dilatation, the mother was placed at the positions, such as dangle, squatting, and hands and knees, which were effective in the fetus’ head descent[18] [Figure 1]. The positions were selected in such a way that they prevented fatigue and monotony of the condition. Moreover, 20 minutes was considered for changing the mothers’ position during labor, because during the active phase, the cervix opens for 1.2–1.5 cm each hour and as the delivery progresses, the pain and anxiety increase.

Figure 1.

Mother's position. (Reference: www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/comfort-in-labor-simkin.pdf)

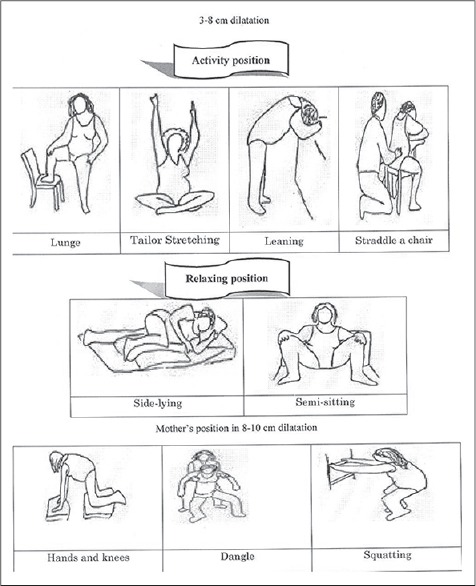

In the second group, in the 3–4 and 7–8 cm dilatations, the mother was placed in a proper position and the BL32 point was pressed. This point lay approximately one index finger length above the top of the buttock crease, approximately one thumb width on either side of the spine[19] [Figure 2]. The pressure was continuously and gently applied by both thumbs for 20 minutes. It was applied at the beginning and stopped at the end of the contractions. On the other hand, the control group only received the department's routine care and underwent no interventions.

Figure 2.

Acupressure point. (Reference: http://acupunctureschoolonline.com/bl-31%E2%80%93bl-34-eight-liao-baliao-acupuncture-points.html)

Finally, the data were analyzed using the SPSS16 statistical software (Ver. 16). The qualitative variables were compared through the Chi-square test. In addition, one-way analysis (ANOVA) was used in order to compare the quantitative variables and in case the results were significant, a post-hoc test was utilized to identify the different groups. Besides, P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

This research project was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.approval code is CT-P-6356.

In this study informed consents were obtained from all the participants.

RESULTS

In this study, no significant difference was found among the groups regarding the number of pregnancies, cervical dilatation at the beginning of the study (3–4 cm), age, level of education, occupation or gestational age (37–41 weeks) (P > 0.005). The highest and lowest frequencies were related to the 21–25 (30%) and 31–35-year-old age groups (19.3%), respectively. With regard to the level of education, the highest and lowest frequencies were related to middle school (43.3%) and academic degrees (23.3%), respectively. Distribution of occupation was also similar in the three study groups and most of the subjects were homemakers (74.7% compared to 25.3% employees). Besides, the highest and lowest gestational age was 41.2 and 37.0 weeks, respectively, and the mean gestational age was 38.9± 1.1 weeks.

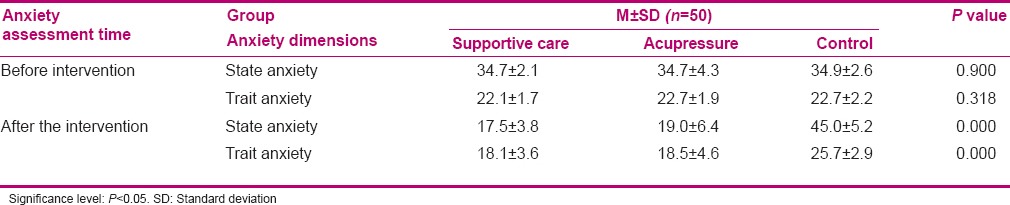

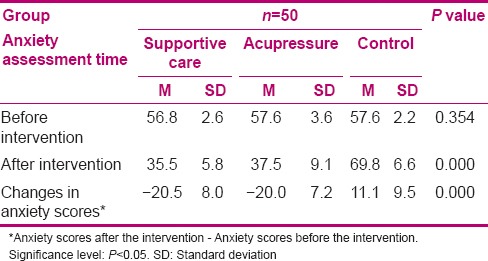

According to the results of one-way ANOVA, no significant difference was found among the three groups regarding the state (P = 0.900) and trait anxiety (P = 0.318) before the intervention. After the intervention (at the end of the first stage), however, the control group's mean score of state anxiety was 27.5 and 26.0 points higher than those of the supportive care and acupressure groups, respectively. Also, the control group's mean score of trait anxiety was 7.6 and 7.2 points higher than those of the supportive care and acupressure groups, respectively, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of various aspects of anxiety before and after the intervention in the three groups

The results of one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference among the three study groups regarding the total score of anxiety before the intervention (P = 0.354).

At the end of the first stage, the mean score of anxiety increased by 21.1% in the control group, while it decreased by 37.5 and 34.8% in the supportive care and acupressure groups, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

The mothers’ mean score of anxiety (state and trait) before and after the intervention in the three groups

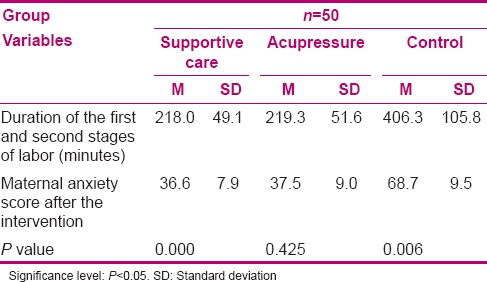

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient revealed a significant relationship between the length of the first and second stages of labor and the mothers’ anxiety score after the intervention in the supportive care (P < 0.001) and the control groups (P = 0.006). However, this relationship was not significant in the acupressure group (P = 0.425). The highest mean length of the first and second stages of labor and the highest mean score of anxiety were related to the control group. On the other hand, the lowest mean length of the labor stages and the lowest mean score of anxiety were related to the supportive care group [Table 3].

Table 3.

The relationship between the length of the first and second stages of labor and maternal anxiety scores after the intervention in the three groups

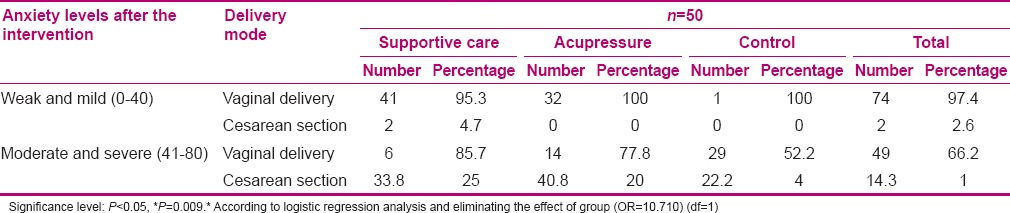

Using logistic regression analysis and eliminating the group effect, a significant relationship was observed between the mothers’ anxiety level after the intervention and the delivery mode (P = 0.009). As the anxiety level increased, the rate of Cesarean section also increased in the three study groups [Table 4].

Table 4.

The relationship between the maternal anxiety levels and types of delivery mode in the two intervention groups (supportive care and acupressure) and the control group

DISCUSSION

The study results revealed a decrease in the supportive care and acupressure groups’ state and trait anxiety scores after the intervention (at the end of the first stage). However, the state and trait anxiety mean scores increased in the control group.

Taking into consideration the supportive care group, the present study results were in line with those of the studies by Hofmeyr[20] and Scott.[21] Hofmeyr stated that supporting the mother through labor could cause considerable changes in the delivery process, including reduction of the mother's anxiety. In Scott's study also, the women supported by the doula had lower state anxiety, positive delivery experience, and higher self-confidence. Furthermore, Teixeira et al., (1999), investigated the relationship between the mother's anxiety and increase in vascular resistance of the uterine arteries. They found a significant relationship between the increase in vascular resistance of the uterine arteries and the state and trait anxiety scores, which was more significant with regard to the state anxiety.[22] Pilkington et al., (2007), also expressed the effect of acupressure on the patients’ anxiety level, based on the Spielberger scale.[23] Therefore, it could be concluded that the mother's anxiety, which was accompanied by an increase in uterine vessel resistance and decrease in oxygenation, played a major role in the fetal as well as maternal outcomes. This emphasized the necessity for performing interventions through labor in order to reduce the mothers’ anxiety.

After the intervention (at the end of the first stage) in the current study, the mean score of anxiety increased in the control group, while it decreased in the supportive care and acupressure groups, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Various studies have shown that acupressure, without any complications, controls and reduces anxiety by stimulating brain responses and hormonal activities, by increasing the blood flow and mediating the metabolism.[24] Chao et al., (2007), also performed acupressure at various points and expressed that this non-pharmacological method was effective in the reduction of women's pain and anxiety during labor. These results were consistent with those of the present study, as a 34.8% decrease was observed in the acupressure group's anxiety score after the intervention in this study.[13]

Mendez and Davim investigated the non-pharmacological methods, such as moving and changing the pregnant women's positions, and concluded that in addition to being appropriate and practical, these methods were highly effective in improving the delivery pain. Pain and anxiety have mutual effects; that is, as one decreases, the other decreases, as well.[25,26] These findings were in agreement with those of the present study.

In contrast to the present study results, Langer et al., (1998), showed that supporting the women through labor was not effective in the need for medical interventions and mothers’ anxiety, pain, self-confidence, and satisfaction.[27] The difference between that study and the present one might be due to the intervention methods, hospital policies, women's cultural background, short period of support, and types of activities of the doulas’. Yet, the support provided by the nurses and the staff might have also been effective in reducing the difference between the two groups.

In the present study, the mean length of the first and second stages of labor in the control group was 187.3 and 188.3 minutes higher compared to that of the supportive care and acupressure groups, respectively. Also, the control group's mean score of anxiety was 69.5 and 72.3 points higher compared to the supportive care and acupressure groups. Essentially, effective and continuous support during labor and delivery turns off the fear-stress-pain cycle.[28] Continuously supporting the mothers during labor and delivery not only reduces their pain and worry, but it also creates a calmness and leads to secretion of catecholamines. Therefore, it reduces the pain, decreases the length of delivery by improving the uterine contraction power, and leads to progress of the physiological delivery.[29]

According to the present study findings, the supportive care group's mean score of anxiety was lower in comparison to the acupressure and control groups. Consequently, the length of the first and second stages of labor was also lower in the supportive care group. Saisto et al., (1999), stated that labor pain mostly results from anxiety, which slows the delivery process down. In addition, they showed that by reducing the anxiety, labor took a shorter period of time.[30] The results of the present study were in agreement with those of the study by Saisto.

The findings of the current study have revealed no significant relationship between the labor length and the mother's anxiety in the acupressure group after the intervention. Several studies have shown that acupressure leads to release of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, which can affect the individuals’ tranquillity.[31,32] Other studies have also indicated that acupressure leads to the release of special peptides, which have analgesic and sedative effects. They particularly reduce the sympathoadrenal system's activity, which is activated during anxiety and labor.[33] In the present study, the three groups were similar with respect to the state and trait anxiety at the beginning of the study. After the intervention, the length of the labor stages and anxiety were lower in the acupressure group compared to the control group; however, no significant relationship was found between the labor length and the mean score of anxiety. As BL32 was one of the effective points in delivery augmentation,[34] acupressure at this point strengthened the uterine contractions. As the contractions are more effective and the interval between the contractions is shorter, labor lasts for a shorter period of time. Although the level of anxiety was lower in the acupressure group compared to the control group, acupressure at the BL32 point was effective in reducing the length of the labor stages. This might have caused the insignificant relationship between the labor length and the mean score of anxiety.

In the control group, the mean score of anxiety and length of the first and second stages of labor were higher compared to the supportive care and acupressure groups, which might explain the significant relationship between the labor length and the mean score of anxiety in the control group. In this regard, Enkin (1996), stated that anxiety decreased the effective uterine contractions through increasing the secretion of the mother's plasma catecholamine, which had a negative impact on the uterine blood flow.[35]

In the current study, the highest rate of Cesarean delivery (40.8%) was related to the control group with average and severe anxiety levels, while the lowest rate (14.3%) was related to the supportive care group with mild anxiety levels.

Stress and anxiety led to secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine. Via the beta-adrenergic receptors in the uterus, epinephrine led to uterine muscle hypoxia, disruption in the uteroplacental blood perfusion, and fetal hypoxia. In addition, via alpha-adrenergic receptors, norepinephrine caused disruption in uterine contractions and slowed down the delivery progress,[36] which might be effective in the performance of the Cesarean section. In general, the mother's anxiety level is related to the incidence of an emergency Cesarean section during labor.[37]

Doula as a supportive person increases the woman's self-confidence and helps her adapt to the delivery process and pain.[38] During the painful uterine contractions, the doula also helps the mother to maintain her tranquillity and control, instead of showing anxious and restless reactions, which facilitate the natural process of the delivery. Biologically, it is assumed that reducing the mother's stress and creating a calm, noiseless environment, leads to the release of oxytocin and this shows the key role played by the doula.

In this study, the anxiety level and rate of Cesarean section were lower in the two intervention groups compared to the control group, which was consistent with the studies by Hodnett,[39] Zhang,[40] Scott,[41] Klaus,[42] Hatem,[43] Albers,[44] and Chang.[45] In these studies also, doula support and acupressure increased the mothers’ self-confidence, reduced their anxiety, and decreased the rate of Cesarean delivery. In the same line, Saisto[30] and Teixeira[22] mentioned that the mother's anxiety was related to an increase of vascular resistance, increase of labor pain, and low labor progress, which increased the chance of a Cesarean delivery.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the present study and similar studies conducted on the issue showed that doula supportive behaviors, including physical and psychological support and changing the mother's positions during labor, through creating an effective relationship with the woman in labor and drawing her active cooperation through the delivery process, could decrease the extra anxiety and tension, reduce anxiety during the delivery process, and make the delivery a desirable experience. Thus, considering the national and international approach toward physiological delivery, this inexpensive, available method, which can easily be taught and executed, is recommended to be used when faced with delivery pain. The findings of the current study also showed that acupressure at the BL32 point for 20 minutes decreased the anxiety level during labor pain. Thus, acupressure could also be used as a simple, inexpensive, non-invasive method for reducing stress during labor.

In this manner, pregnant women are persuaded to select natural vaginal delivery and experience the delivery process with lower stress, which eventually leads to reduction in the rate of Cesarean deliveries and their resultant complications, as well as in the treatment expenditure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The present article was extracted from Mrs. Zahra Masoudi M.Sc. thesis (proposal NO. 6356, IRCT 2012120911706N1). The study was financially supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Hereby, the authors would like to thank the authorities of the college of nursing and midwifery and physicians and midwives of Shoushtari hospital, Shiraz, Iran. They are also grateful for Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stager L. Supporting women during labor and birth. Midwifery Today Int Midwife 2009. 2010;92:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderdice F, Lynn F. Factor structure of the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire. Midwifery. 2011;27:553–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Körükcü Ö, Fırat MZ, Kukulu K. Relationship between fear of childbirth and anxiety among Turkish pregnant women. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2010;5:467–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCrea H, Wright ME, Stringer M. Psychosocial factors influencing personal control in pain relief. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2000;37:493–503. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simkin P, Bolding A. Update on Nonpharmacologic Approaches to Relieve Labor Pain and Prevent Suffering. Midwifery & Women's Health. 2004;49:489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sosa R, Kennell J, Klaus M, Robertson S, Urrutia J. The effect of a supportive companion on perinatal problems, length of labor, and mother-infant interaction. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:597–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198009113031101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundgren I. Swedish women's experiences of doula support during childbirth. Midwifery. 2010;26:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliland AL. After praise and encouragement: Emotional support strategies used by birth doulas in the USA and Canada. Midwifery. 2011;27:525–31. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melzack R, Belanger E, Lacroix R. Labor pain: effect of maternal position on front and back pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6:476–80. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(91)90003-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennel J, Klaus M, McGrath S, Robertson S, Hinkley C. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;265:2197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yip YB, Tse SHM. The effectiveness of relaxation acupoint stimulation and acupressure with aromatic lavender essential oil for non-specific low back pain in Hong Kong: A randomised controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2004;12:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung UL, Hung LC, Kuo SC, Huang CL. Effects of LI4 and BL 67 acupressure on labor pain and uterine contractions in the first stage of labor. J Nurs Res. 2003;11:251–60. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000347644.35251.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao A-S, Chao A, Wang T-H, Chang Y-C, Peng H-H, Chang S-D, et al. Pain relief by applying transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on acupuncture points during the first stage of labor: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. PAIN. 2007;127:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal A, Ranjan R, Dhiraaj S, Lakra A, Kumar M, Singh U. Acupressure for prevention of pre-operative anxiety: a prospective, randomised, placebo controlled study. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:978–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajiamini Z, Masoud SN, Ebadi A, Mahboubh A, Matin AA. Comparing the effects of ice massage and acupressure on labor pain reduction. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2012;18:169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI (Form Y)(“ Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”).Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghamohammadi M. Religious preoperative anxiety. Annual of General Psychiatry. 2008;69:1195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simkin P. The Birth Partner-Revised 3 rd Edition: A Complete Guide to Childbirth for Dads, Doulas, and All Other Labor Companions: Download iTunes eBook. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim S. WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2010;7:167–8. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmeyr GJ, Nikodem VC, Wolman W, et al. Companionship to Modify the Clinical Birth Enviorment: Effects on progress and perceptions of Labour and Breast Feeding. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;98:756–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott KD, Klaus PH, Klaus MH. The obstetrical and postpartum benefits of continuous support during childbirth. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:1257–64. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teixeira JM, Fisk NM, Glover V. Association between maternal anxiety in pregnancy and increased uterine artery resistance index: cohort based study. BMJ. 1999;318:153–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Cummings M, Richardson J. Acupuncture for anxiety and anxiety disorders: A systematic literature review. Acupunct Med. 2007;25:1–10. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.1-2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelman M, Ficorelli C. A measure of success: nursing students and test anxiety. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2005;21:55–9. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200503000-00004. quiz 60-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendez-Bauer C, Arroyo J, Garcia Ramos C, Menendez A, Lavilla M, Izquierdo F, et al. Effects of standing position on spontaneous uterine contractility and other aspects of labor. J Perinat Med. 1975;3:89–100. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1975.3.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davim RM, Torres Gde V, Melo ES. Non-pharmacological strategies on pain relief during labor: pre-testing of an instrument. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2007;15:1150–6. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langer A, Campero L, Garcia C, Reynoso S. Effects of psychosocial support during labour and childbirth on breastfeeding, medical interventions, and mothers’ wellbeing in a Mexican public hospital: A randomised clinical trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1056–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albers L. The evidence for physiologic managment of the active phase of the first stage of labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen P. Supporting women in labor: analysis of different types of care givers. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saisto T, Ylikorkala O, Halmesmaki E. Factors associated with fear of delivery in second pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:679–82. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyoshi J. [Neuropharmacological and genetic study of panic disorder] Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1999;19:93–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ninan PT. The functional anatomy, neurochemistry, and pharmacology of anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 22):12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotani N, Hashimoto H, Sato Y, Sessler DI, Yoshioka H, Kitayama M, et al. Preoperative intradermal acupuncture reduces postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, analgesic requirement, and sympathoadrenal responses. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:349–56. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook A, Wilcox G. Pressuring pain. Alternative therapies for labor pain management. AWHONN Lifelines. 1997;1:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.1997.tb00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enkin C. Oxford university press; 1996. A guide of effective care pregnancy & childbirth. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campell DA, Lake MF, Falk M. A Randomized Control Trial of Continuous Support in Labour by a Lay Doula. J obstet and Gynecol Neonatal Nursing. 2006;35:456–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryding EL, Wijma B, Wijma K, Rydhstrom H. Fear of childbirth during pregnancy may increase the risk of emergency cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:542–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodnett E. Nursing support of the laboring woman. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1996;25:257–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodnett ED. Caregiver support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000199. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Bernasko JW, Leybovich E, Fahs M, Hatch MC. Continuous labor support from labor attendant for primiparous women: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:739–44. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott KD, Berkowitz G, Klaus M. A comparison of intermittent and continuous support during labor: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:1054–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klaus MH, Kennell JH. The doula: an essential ingredient of childbirth rediscovered. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:1034–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb14800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatem M, Sandall J, Devane D, Soltani H, Gates S. Midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;8:CD004667. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albers LL, Anderson D, Cragin L, Moore Daniels S, Hunter C, Sedler KD, et al. The relationship of ambulation in labor to operative delivery. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1997;42:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(96)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang SB, Park YW, Cho JS, Lee MK, Lee BC, Lee SJ. Differences of cesarean section rates according to San-Yin-Jiao(SP6) acupressure for women in labor. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2004;34:324–32. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2004.34.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]