Abstract

Background:

Fertility rate apparently is a non-interventional behavior, but in practice, it is influenced by social values and norms in which culture and traditional beliefs play a significant role. In this regard, some studies have shown that gender roles can be associated with reproductive behaviors. With regard to the importance of annual reduction of population growth rate and its outcomes, the present study was performed to determine the relationship between gender role attitude and fertility rate in women referring to Mashhad health centers in 2013.

Materials and Methods:

The present study is an analytical cross-sectional and multistage sampling study performed on 712 women. Data were collected by a questionnaire consisting of two sections: Personal information and gender role attitude questionnaire that contained two dimensions, i.e. gender stereotypes and gender egalitarianism. Its validity was determined by content validity and its reliability by internal consistency (r = 0.77). Data were analyzed by SPSS software version 16.

Results:

Initial analysis of the data indicated that there was a significant relationship between acceptance of gender stereotypes (P = 0.008) and gender egalitarianism (P < 0.001), and fertility. There was also a direct association between acceptance of gender stereotypes and fertility rate (r = 0.13) and an indirect association between egalitarianism and fertility rate (r = −0.15).

Conclusions:

The results of the present study indicate that there is an association between gender role attitude and fertility. Paying attention to women's attitude is very important for successful planning in the improvement of fertility rate and population policy.

Keywords: Attitude, fertility rate, gender role, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Fertility is one of the main components of population growth about which extensive international and domestic research has been conducted to identify its factors.[1,2] Therefore, measurement of the rate of fertility and its effective factors is considered as the basic parameter not only in population expectations but also in the assessment of economic and social status of the society.[1] Iran is currently experiencing a decline in fertility.[3] In this context, the results of census statistics show that the average annual population growth in Iran has reached from 3.25 in 1991 to 1.62 in 2006 and 1.3 in 2011.[4] The decrease in fertility leads to population aging that affects the size and composition of the labor force, which plays an important role in economic growth.[5]

Fertility seems to be a behavior not needing any intervention; but in practice, it is influenced by the social values and norms in which cultural and traditional beliefs of people play a significant role. In this regard, some studies have shown that gender role can be associated with reproductive behaviors.[3,6]

Gender role is a broad concept and is defined as a set of behaviors, attitudes, and personality characteristics in a particular culture,[2] based on which many of the responsibilities and duties of the family are defined.[7] Gender role attitude is people's beliefs about the roles and responsibilities and the behavioral tendencies of women and men.[8]

Among the aspects of gender role attitudes are gender stereotypes and gender egalitarianism. Gender stereotypes are beliefs and attitudes about masculinity and femininity,[9] and emphasize on the unequal distribution of power in the family and stereotype norms.[10] Gender egalitarianism attitudes emphasizes on the common features in economic production, family training, and power, and the equal distribution of professional responsibilities and family life between women and men.[11]

The relationship between gender role and fertility has been assessed in a few studies. The fact is that changes in gender roles have different effects on men and women.[12] Different views on gender roles in families create differences in individual behavior that ultimately affect the decision-making process in the family.[13]

Based on the findings of Jones and Brayfield (1997) and some results of Bernhardt and Goldscheider (2006) in Sweden, the gender revolution has led to the liberal attitudes to gender roles, and women and men are becoming more aware of the plights of being parents.[14] Also, according to some studies, the division of gender labor at home is associated with the first and second births.[14,15] A study in Sweden has reported that gender role attitude was effective on understanding the costs and benefits of having children, and egalitarian women perceived the benefits of having children less than the women with traditional gender role attitudes.[12]

Gender revolution in Europe and the women's double burden of work-related activities within the home and outside the home have been mentioned as two reasons for the rapid and sustained decline in fertility and not having children in the late 20th century.[16] In this way, in smaller families, women are more equal to men; but at the same time, provision of child care by close relatives is decreased. On the other hand, women's stress has been increased due to increase in their burden, caused by the combination of job activities and household work.[14]

Today, young women have more options in terms of opportunities related to education, family, and career life.[17,18] An increase in education level and participation in labor force, especially for women, result in the creation of modern gender roles and different expectations of life.[19] However, a woman who competes in the public sphere on the basis of gender equality is expected to be responsible for housekeeping and child care at the same time. As a result, the perceived cost of having the first child or other children is high in these women.

In today's modern society, the equality of women and men in the labor market gives an excellent situation to the women which competes with their household work. On the other hand, child birth decreases women's overall revenue, or in some cases, reduces women's opportunities due to the reduction in a part of time devoted to professional activities or temporary or permanent withdrawal from work. In other words, double imposed burden under these circumstances is considered as a detrimental option for women and motivates them less toward having children.[16]

The impact of gender equality on fertility depends on nationality and social background. In this regard, several studies showed that fertility increased with increasing gender equality in the family. For example, McDonald (2000) in his study on the dynamics in gender of the family reported no imbalance between high gender equality in education and the employment in market. He also reported that the lower level of gender equality in family life caused low fertility in the developed countries.[14]

Regarding the decline in the rate of population growth and the incremental change in the family size in Iran, and as recognizing the reproductive behavior of the couples and having infrastructure information are essential in offering the educational programs in order to promote fertility, the researcher decided to perform the present study to determine the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility in women referring to health centers of Mashhad in 2013.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was performed on the women referring to health centers of Mashhad, Iran in 2013. The sample size was 712 women. Sampling was conducted from November to September 2013 (for 4 months) in multistage from all the health centers of Mashhad. Firstly, public health centers under the coverage of five health centers of Mashhad (No. 1, 2, 3, 5, and Samen) were classified, and the statistics were obtained on the clients covered by each health center. Then, their covered health centers were listed and some of the health centers were selected as the clusters by lotto draw method. In each center, the samples were selected from among the available subjects meeting the sampling criteria.

Ethical considerations

Subjects were enrolled after obtaining an informed consent form from them. To collect the information, the interview was conducted in two parts inquiring the demographic characteristics of the subjects and their spouses, families, and children, and their medical and midwifery information, and gender role attitudes questionnaire of Kiani (2008), which consisted of 45 items scored by a five-point Likert’ scale from “absolutely disagree” to “absolutely agree.” Most of the items were scored by direct method (absolutely disagree, score 1; and absolutely agree, score 5), and some items were scored by reverse method (absolutely disagree, score 5; and absolutely agree, score 1). With regard to the dimension of gender egalitarianism, the scores ranged from 37 to 185. A higher score indicated more gender egalitarianism. With regard to the dimension of gender stereotypes, the scores ranged from 8 to 40 and a higher score showed that people could accept stereotypical gender more.

Samples included married biological mothers in all age ranges with any number of children. Pregnant women with a history of infertility and the women with abnormal children were excluded from the study.

To determine the validity of the tools in this study, the content validity was used. The questionnaires were given to the faculty members of Nursing and Midwifery School (n = 10), epidemiologists of the Health Department (n = 2), and the sociologists of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad (n = 2). Its reliability was calculated by the internal consistency and the computation of Cronbach alpha (α =0.77). After recording and collecting the data, the analysis was performed by SPSS software version 16. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of the data. Linear correlation between variables was calculated by Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. For pair comparison, anaysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey methods were adopted.

RESULTS

In this study, 712 women were evaluated. Mean age of the subjects was 30.89 (8.05) years and their age ranged between 15 and 66 years. Also, 44% of the women had high school education and 76% of the women were homemakers. Mean number of children was 1.72 (1.12) and the number ranged between 0 and 6 (boys with a mean of 0.88 ± 0.87 and girls with a mean of 0.86 ± 0.88, with a sex ratio of 1:1).

Descriptive statistics evaluation showed that in terms of the dimensions of gender role attitudes, the mean score of gender stereotypes was 29.55 (4.32), with a range of 8–40, and the mean score of gender egalitarianism was 112.55 (14.46), with a range of 65–158.

There was a statistically significant difference between age and egalitarian gender role attitudes in the studied women (P = 0.04), but there was no statistically significant difference between age and gender stereotypes in women (P = 0.10). In order to compare the mean scores of gender role attitudes based on women's age, the scores of two dimensions were calculated from 100 using the formula

[Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of stereotype gender role and egalitarian gender role based on age in females

The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference between gender stereotypes (P = 0.008) and gender egalitarianism (P < 0.001), and the number of children in women with a coefficient level of 95%.

The calculated correlation coefficient for gender stereotypes was positive (r = 0.13), which means that more gender stereotypes of the women leads to having more number of children, whereas the calculated correlation coefficient for gender egalitarianism was negative (r = −0.15), which represents an inverse relationship between gender egalitarianism and the number of the children in the studied women.

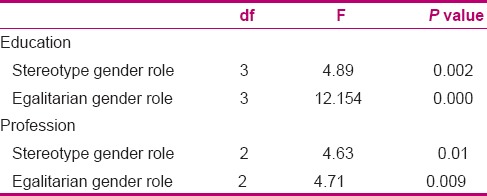

Also, ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of education and job on gender egalitarianism characteristics. Results showed that there was a statistically significant difference between subjects’ job and education and their gender role attitudes [Table 1].

Table 1.

Relationship of gender role attitudes, and women's education and employment

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that in women of different ages, egalitarian gender role attitudes were different, but there was no significant difference in gender stereotypes. In this study, a significant association was observed between the dimensions of gender role attitudes and fertility rate in such a way that the egalitarian gender role attitudes increased in young women, compared to the older women. This is possibly due to a change in the social status of women in recent years and an increase in their participation in social, economic, and political activities.[9,20]

Cotter et al. reported in USA that gender role attitudes have changed from 1974 to 1994 and they have been leaning on gender egalitarianism more, possibly due to the activities related to feminism in the US during this period. Meanwhile, after this period, it was placed aside in the middle of 90s and has not shown increase.[20]

The findings of this study suggest that there is a relationship between gender role attitudes and the number of children, which is in accordance with the study of Henz in Germany.[6] Meanwhile, it is different from the results of Bernhard and Goldscheider in Sweden[12] and Miettinen et al. in Finland[14] who reported that there was no relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility. The difference may be due to the difference in sampling techniques and tools used. In the study of Bernhard and Goldscheider, gender role attitudes questionnaire included three items and was sent by email, while in the present study, the gender role attitudes questionnaire contained 45 items and the questionnaires were completed in the presence of the researcher and in the health centers, which led to different conditions of accountability and accuracy. Miettinen et al.'s study was performed on women aged 25–44 years, without children or with one child, while the present study was conducted in women aged 15–66 years with no limitation in the number of children. In the study of Miettinen et al., the women's intention of fertility was also considered in calculation, while in the present study, the number of existing children was determined.

The findings of this study showed that there was a relationship between gender egalitarianism and gender stereotypes, and the number of children in women, which is in line with the study of Spéder and Kapitány in Hungary reporting that more traditional gender attitudes were associated with having second and third children both among men and women.[21] Meanwhile, it is not consistent with the results of Bernhard and Goldscheider[12] and Miettinen et al.[14] reporting no association between gender role attitudes and fertility.[12,14]

In the study of Bernhard and Goldscheider, gender role attitudes were not effective on women's motherhood and the birth of their first child in the next 4 years. It could be due to the fact that in the study of Bernhard and Goldscheider, only one aspect of gender role attitudes was emphasized and the gender role attitudes toward pre-school children were measured while other roles of life were not investigated. In their study, 25.4% of the women were without a partner, 26% had a steady partner, 44.9% had a partner in a shared house (in the house), and 3.8% were married, while in our study, 92.3% were married, 1.8% were divorced, and 1% were widowed. Therefore, the difference in subjects’ marital status may have affected the results of the present study. On the other hand, in the study of Miettinen et al.,[14] some questions related to gender egalitarianism were included in a separate questionnaire, named as family orientation, and the number of the desired children (desired family size in the future) which is a poor predictor for the outcome of fertility behavior was assessed.

In the study of Henz in Germany, it was reported that the first birth occurred earlier among the couples with traditional gender role attitudes while the behavior of the couples who believed in gender equality was related to the emotional value of the children and was changeable. These findings may be due to the fact that in women with traditional gender role attitudes, motherhood can be regarded as a central element of their social life, affecting their reproductive behavior.[6]

The findings of this study suggest that gender egalitarianism has a negative association with fertility rate in such a way that egalitarian attitudes are associated with a lower fertility rate. The gender stereotypes have a direct association with the number of the children and are associated with a higher fertility rate, which is consistent with the results of Kaufman in USA who reported that the egalitarian women intended to have a child less than traditional women.[15] However, Torr and Short in USA found that there was a U-shaped relationship between the division of gender labor at home and the birth of the second child in such a way that “modern” couples in whom home tasks are shared and “traditional” couples in whom women do housework more have more children than the intermediate group.[22]

This difference in findings may be due to the effects of cultural, social, and economic factors and the differences in geographic areas and in the policies of different governments. On the other hand, couples with egalitarian gender role attitudes tend to choose their own lifestyle more. Therefore, they may reflect the threats of their work dimensions in their parental behavior.[6] One of the most noteworthy findings in the investigation of the relationship between gender roles and women's fertility is that when the women notice their “traditional” gender role less, they accept the roles beyond the home and family and participate in social activities such as business activities more; they have fewer children in their life and have baby later. Their new role requires them to focus more on life compared to fertility. All these factors greatly increase their maternal age.[12]

Revolutionary theory states that gender equality in societies where gender equality has reached within the family has led to reinforcement of fertility.[14]

Regarding the decline in fertility rates and changing roles in Iran, the findings of the present study demonstrate the importance of understanding the changes in gender role attitudes at the family level. Revolutionary theory argues that gender equality should now reinforce the fertility, especially in the communities where this equality has reached within the family. An appropriate division of labor between couples, whether egalitarian or traditional, can lead to a balance between work and family.[14] Sharing roles including the roles related to caring of children, especially in young couples, can be useful. According to the view of global organization of power in 2004, during the gender revolution, when men participate in housework and child care as equally as women, women's participation in their roles such as motherhood will increase.[12]

In the present study, there was a correlation between education level and gender role attitudes, which is in line with the results of Kiani and Taromian[7] in Zanjan and Wernet et al. in USA.[23] Justifying these results, it can be said that women want to change their gender roles,[7] and the egalitarian women focus more on higher education and its consequences than the women with traditional gender role attitudes.

In our study, a statistically significant relationship was observed between occupation and gender role attitudes which is consistent with findings of Stickney and Konrad;[24] but in the study of Zhang, no relationship was found between the jobs of Chinese students’ parents and gender egalitarianism,[25] which is different from the findings of the present study. This difference may be due to differences in the culture of the societies studied and the fact that the students’ partner jobs were assessed while the employment status of the students was not investigated. These findings may be because of the fact that people with different occupational positions have different values. On the other hand, women with egalitarian attitudes accept their roles beyond the home and family and participate more in social activities such as working activities.[12]

Among the limitations of this study, no assessment made of the gender role attitudes of the husbands could be pointed out. In addition, in this study, no information about the quality of the marital relationship and the life satisfaction level of the studied women was available which may also have affected fertility behavior in women.

It is recommended to investigate gender role attitudes to evaluate the different elements influencing the family and fertility in Iran among different cultural, ethnic, and religious groups. It is also recommended to conduct further studies to evaluate the relationship between gender role attitudes of husbands and fertility, and to control the variables influencing marital quality and life satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that gender role attitudes are associated with fertility. With regard to the importance of fertility as one of the main components of population growth, the results of this study can provide new perspectives to compile comprehensive and regular training programs to improve the reproductive behavior in women. In this regard, we can plan and implement the necessary policies in the field of holding counseling psychology classes for the counselors, educators, and other staff providing health services, in order to train women about reproductive behavior and to provide them the needed facilities and lead the individuals toward valuable and voluntary childbearing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the professors and members of the Research and Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and the staff of health centers of Mashhad, as well as all those who participated in this project. This article was derived from a master thesis of Name of student Elham Fazeli, Project Name: Assessment of Relationship Value of Children, Gender Role Attitude and Number of Children among Women Referred to Health Centers in Mashhad with project number 920362 Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research Deputy, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adibi M, Arjmand E, Darvishzadeh Z. Assessment of fertility and its influencing factors among Kurdish clans in Andimeshk. Stu Soc Dev. 2011;1:81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Laroche M, Tomiuk MA. The Chinese in Canada: A study in ethnic change with emphasis on gender roles. J Soc Psychol. 2004;144:5–29. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.144.1.5-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keshavarz H. Factors affecting reproductive behavior of different between non-immigrant and immigrant tribes in Semirom. J Health Syst Res. 2012;8:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General population and housing census preliminary results 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 13]. Available from: http://www.amar.org.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=123 and ArticleType=ArticleViewandArticleID=8 .

- 5.Darabi S. Socioeconomic Consequence of Population Aging in Iran. Soc Sci. 2012;4:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henz U. Gender roles and values of children: Childless couples in East and West Germany. Demogr Res. 2008;19:1451–500. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiani GB, Taromian F. Study of the attitude toward gender role on submit gender egalitarianism among university students and employees in Zanjan. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci Health Ser. 2009;17:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:573–84. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagheri MS. The effect of women employment on family hierarchy. J Fam Res. 2009;5:262–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santana MC, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J Urban Health. 2006;83:575–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazik NA. Washington, D.C: General University Honors; 2011. Gender Role Attitudes in Youth. Washington research library Consortium: American University. Professor Noemi Enchautegui de Jesus. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernhardt E, Goldscheider F. Gender equality, parenthood attitudes, and first births in Sweden. In: Tomas Sobotka., editor. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. Vol. 4. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography; 2006. [Last accessed on 2007 Feb 15]. pp. 19–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2006s19”10.1553/populationyearbook2006s19 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C, Beatty S. Family structure and influence in family decision making. J Consum Mark. 2002;19:24–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miettinen A, Basten S, Rotkirch A. Gender equality and fertility intentions revisited: Evidence from Finland. Demogr Res. 2011;24:469–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman G. Do gender role attitudes matter? Family formation and dissolution among traditional and egalitarian men and women. J Fam Issues. 2002;21:128–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benardi L, Ryser V, LeGoff J. Gender Role-Set, Family Orientations, and Women's Fertility Intentions in Switzerland. Swiss J Sociol. 2013;39:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beyerlein M. Denton, Texas, USA: University of North Texas; 2007. Women's gender role attitude: Association of demographic characteristics, work related factor and life satisfaction. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motiejunaite AK. Family policy, employment and gender-role attitudes: A comparative analysis of Russia and Sweden. J Eur Soc Policy. 2008;18:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liefbroer A. The impact of perceived costs and rewards of childbearing on entry into parenthood: Evidence from a panel study. Eur J Popul. 2005;21:367–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotter D, Hermsen J, Vanneman R. The End of the Gender Revolution? Gender Role Attitudes from 1977 to 2008. American J Sociol. 2011;117:259–89. doi: 10.1086/658853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spéder Z, Kapitány B. How are time-dependent childbearing intentions realized? Realization, postponement, abandonment, bringing forward. Eur J Popul. 2009;25:503–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torr BM, Short SE. Second births and the second shift: A research note on gender equity and fertility. Popul Dev Rev. 2004;30:109–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wernet CA, Elman C, Pendleton BF. The postmodern individual: Structural determinants of attitudes. Comp Soc. 2005;4:339–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stickney L, Konrad A. Gender-role attitudes and earnings: A multinational study of married women and men. Sex Roles. 2007;57:801–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang N. Gender role egalitarian attitudes among Chinese college students. Sex Roles. 2006;55:545–53. [Google Scholar]