Abstract

Introduction:

The extent of neuromeningeal cryptococcosis (NMC) has increased since the advent of HIV/AIDS. It has non-specific clinical signs but marked by high mortality.

Objective:

To analyze the characteristics of the NMC in sub-Saharan Africa.

Materials and Methods:

We have conducted a literature reviewed on the NMC in sub-Saharan Africa from the publications available on the basis of national and international data with keywords such as “Cryptococcus, Epidemiology, Symptoms, Outcomes and Mortality” and their equivalent in French in July 2011. All publications from 1990 to 2010 with 202 references were analyzed. The following results are the means of different studied variables.

Results:

We selected in final 43 publications dealing with the NMC which 24 involved 17 countries in Africa. The average age was 36 years old. The average prevalence was 3.41% and the average incidence was 10.48% (range 6.90% to 12%). The most common signs were fever (75%), headaches (62.50%) and impaired consciousness. Meningeal signs were present in 49% of cases. The mean CD4 count was 44.8cells/mm3. The India ink and latex agglutination tests were the most sensitive. The average time before the consultation and the hospital stay was almost identical to 27.71 days. The average death rate was 45.90%. Fluconazole has been the most commonly used molecule.

Conclusion:

The epidemiological indicators of NMC varied more depending on the region of sub-Saharan Africa. Early and effective taking care of patients to reduce diagnostic delay and heavy mortality remains the challenges.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, epidemiology, neuromeningitis, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Cryptococcosis is a cosmopolitan infection caused by the “Cryptococcus neoformans”. Its course is sub-acute or chronic with a marked opportunistic behavior. Neuromeningeal location caused often fatal meningoencephalitis.[1] In the early 90s, there was a marked increase of the disease related to HIV/AIDS. Epidemiological data are sparse in Africa.[1,2,3,4,5,6] The disease is marked by non-specific constitutional symptoms such as fever, headaches, nausea and vomiting, unconsciousness and rough meningeal signs. This condition often delayed the diagnosis. The objective of this reviewed study was to analyze the epidemiological aspects of neuromeningeal cryptococcosis (NMC) in sub-Saharan Africa in the light of the literature.

Materials and Methods

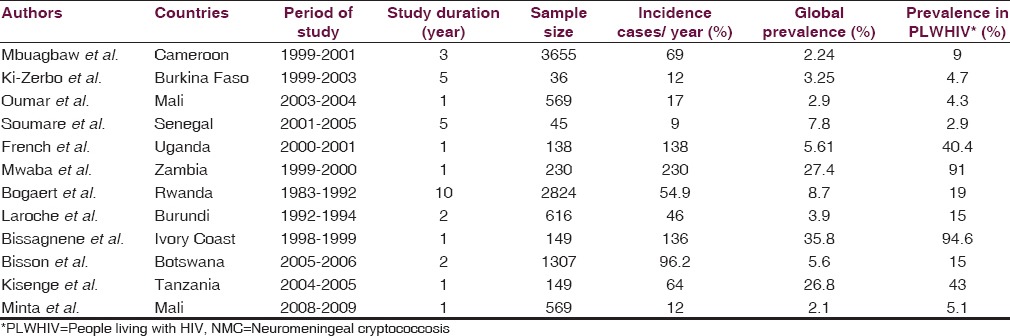

We conducted a literature reviewed on the NMC in sub-Saharan Africa, based on publications in international and national journals. The documentation was based on written and referenced sources. We conducted research references from scientific databases: PubMed, Medline, Google and Medknow bases. The review focused on the following keywords: NMC, epidemiology, clinical features, laboratory findings, antifungal drugs, sub-Saharan Africa with their French corresponding words. We obtained a total of 202 references on all the databases consulted in July 2011. All articles published between 1990 and 2010 were collected. We proceeded to read and select from the abstracts of articles having a structure of original articles of scientific IMRAD kind. We had considered the articles in French and English. The article should focus at least on one of the following variables mentioned above concerning the features of NMC. The study should be conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and/or applied to a sub-Saharan African population. Editorials, general journals and teaching articles, and other aspects of the NMC, as well as papers published outside of our study period, were not retained. We have presented the results as an average of each collected data in Table 1.

Table 1.

Repartition of the NMC according to the sample size, incidence and prevalence rates in different countries reported by authors

Analyze of findings

Our study was a review of the literature on African researches in NMC. It encountered some bias regarding the sub-region and the study period. The sample size was not also uniform across several sites. Another bias was that all aspects have not been assessed by all authors and that had reduced the number of publications finally retained. A multicenter study with a unified protocol may allow overcoming these shortcomings, which do not alter the quality of the study. We identified 43 publications in final processing of the NMC which 24 involved 17 African countries. From these publications only 11 had met our inclusion criteria. The parameters studied were classified into four groups according to whether they relate to each of the aspects raised. For each parameter studied, we did not take into account the numbers of different samples but only the parameter value by publication. Our results are the averages of the findings from different studies, shown in Table 1.

Epidemiological indicators

The sex ratio average was 1.88. This male predominance was reported by most of the studies that we had access.[7,8,9,10] This is contrary to the HIV seroprevalence where the female is dominant worldwide. The average age was 38.02 years ± 4.25 years (range 18 to 65). The age of the young population slice is superimposed on the most affected by HIV/AIDS in the communities.[7,9,11,12] The average incidence rate was 10.48% with a range from 6.90% to 12%. NMC was observed in 85.70% to 97% among HIV + and 7% (range 3% to 10.50%) in HIV-negative patients. NMC affects sub -Saharan African young people with a median incidence of 3.2% in contrast to Western and Central Europe, and Oceania where the median incidence is the lowest around 0.1%.[13] The first case of NMC diagnosed in the UK in 2004 was imported from South Africa by an HIV-positive patient.[14] The number of cases per year is highly variable in Africa from 1 year to another and within the same region. This is remarked in several studies, where the number of cases ranged from 0.75 cases per year in Morocco to 230 cases in Zambia.[7,9,15,16]

The prevalence was 3.41% with a range from 2.24% to 94.6% among people living with HIV and 1.7% in all hospitalized patients (range 0.9% to 26.8%).[17,18]

According to the regional distribution, the prevalence was low, with respective values of 1.7%, 5% and 9% in Central Africa countries.[3,19,20]

In Eastern and Southern Africa regions, the prevalence was very diverse with 7% in Ethiopia,[21] 40.4% in Uganda[17] and 91% in Zambia.[7]

The prevalence was also highly variable and patchy with values between 3.25% and 94.6% in the West African region.[8,22,23] The high prevalence of HIV infection, the ecological environment of Cryptococcus and different research methods used seem to be the best explanation for these variations in prevalence and their impact on available data in our regions. The high frequency of Cryptococcus is highly correlated with the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the Congo Basin, and Southern and West Africa regions.

Clinical aspects

Headaches, fever, altered consciousness and nausea and vomiting are the most frequently encountered symptoms. Headaches and fever usually around 39°C were the most consistent signs.[1] Meningeal signs are present in 49% of cases with extreme of 35.7% to 60%. The oropharyngeal candidiasis and pneumonia tuberculosis were the most common pathologies associated with NMC. Other associated pathologies such as chronic diarrhea, Kaposi's sarcoma and ocular cytomegaloviruses appeared in lower proportions. These conditions are opportunistic infections with clinical signs classifying stages III or IV of HIV/AIDS according to WHO. This explains their concomitant to NMC for which an advanced stage of cellular immunosuppression is a key factor.[5,8,10,15] NMC is the most aseptic meningitis characterized by non-specific general signs and rough meningeal symptoms.[1,6,10,11,17]

Study of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

On CSF study, obtained by lumbar puncture, was performed systematically the search of C. neoformans. On macroscopic examination, the CSF was clear in appearance in 75.1% of cases (57.6% and 89%) with normal or low cytology (4-38 elements/mm3). On biochemical analysis, the average rates of glucose (0.36 g/l) and protein (0.95 g/l) concentration were abnormal. The predominance of the couple hypoglucorrhachial/protein high level is an indicator of aseptic meningitis.[1,5,8,11,15] The Cryptococcus were present in 90.88% on direct examination of CSF in India ink where it was practiced. The research was positive in 20.5% in Burkina Faso,[6] 19% (549/2824) in Rwanda[16] and 15% (193/1307) in Botswana.[24] The culture was positive in Saboureaud medium with 98.40%. The India ink and latex agglutination tests were the most sensitive with an average of 90.88%.[8,10]

Normal cytology is often a misleading element in the NMC, but the rule is not to take it into account and to search Cryptococcus 3-4 times by the India ink test.

According to data from the literature, while someone attributed to the direct examination for a perfect specificity (100%), others felt that it depends on microbiologists, implying the need to confirm any positive results by culture. The sensitivity depends also on several parameters including the thickness of the capsule and the volume of biological fluid seeded. Culture should be a better test with a specificity and sensitivity close to 100%, but is not available in many parts of the continent.[16]

The degree of immunocompromised

Immunosuppressed condition was severe with an average of CD4 count at 44.53 CD4/mm3 (1-187 cells/mm3). The opportunistic nature of cryptococcosis was already known before the era of HIV/AIDS. A severe deficiency of cell-mediated immunity (CD4 count < 100 cells/mm3) is very often the leading factor of NMC.[18,25]

Depending on the HIV status, our results showed that about 7% of subjects were HIV negative. While the NMC is currently a real marker of HIV infection,[8] it remains true that this condition also affects immunocompromised patient by other diseases than HIV[26,27] and even immunocompetent individuals without apparent risk factors.[28]

The duration of disease progression

The mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis and the hospital stay was almost identical to 27.71 days (2-121 days) in several studies.[25,27,29]

Treatment

Fluconazole and amphotericin B were used alone or in combination. Fluconazole is currently widely used alone, 81.25%,[30,31,32] or in combination with flucytosine.[33,34] Amphotericin B is often difficult to access and handle in our regions.[15,28] In a study conducted in Spain in 2000, discharge was favorable for the five patients treated with intravenous amphotericin B associated with flucytosine and fluconazole.[33] A good therapeutic approach is often difficult to do in our communities for reasons of high cost of care and unavailability of drugs.[5,15,28,35,36]

Mortality

Mortality was heavy with 45.9% of deaths (range 42.2% to 71.1%), more than half of the patients died in most studies.[6,7,8,9,10,18] NMC is burdened with a heavy mortality in tropical regions with low income resources countries. This is due to several factors: Expensive and unavailability of drugs, inefficient adapted treatment and limited financial resources among affected patients, in addition to delayed diagnosis due either to rudimentary technical platform or to non-specific signs of the disease.

Conclusion

The neuromeningeal cryptococcosis is a disease under diagnosed in sub-Saharan Africa. In these countries, it affects a young males population severely HIV immunocompromised. The diagnosis is almost a death sentence for patients living with HIV. The data concerning NMC features are patchy and sparse in the sub-Saharan African countries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gari-Toussain M, Mondain-Miton V. Cryptococcosis. In: Medical and Surgical Encyclopedia: Infectious diseases. 1998 8-613-A-10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casadevall A. Estimation of prevalence of cryptococcal infection among patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus in New-York city. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1029–33. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laroche R, Deppner M, N’Dabane ZE. The cryptococcosis in Bujumbura (Burundi) about 80 cases observed in 42 months. Med Afr Noire. 1990;37:588–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muyembe TJJ, Mupapa KD, Nganda L, Ngwala-Bikindu D, Kuezina T, Kela-We I, et al. Cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. Gattii, a case associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Kinshasa, Zaire. Med Trop. 1992;52:435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbuagbaw JN, Biholong NP, Njamnshi AK. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis and HIV infection in the medicine service of the university hospital of Yaoundé-Cameroon. AJNS. 2006;25:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ki-Zerbo G, Sawadogo A, Millogo A, Andonaba JB, Yameogo A, Ouedraogo I, et al. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis during AIDS: A preliminary study in the Bobo-Dioulasso hospital (Burkina Faso). Méd. Afr Noire. 1996;43:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mwaba P, Mwansa J, Chintu C, Pobee J, Scarborough M, Portsmouth S, et al. Clinical presentation, natural history, and cumulative death rates of 230 adults with primary cryptococcal meningitis in Zambian AIDS patients treated under local conditions. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:769–73. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.914.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bissangnene E, Ouhon J, Kra O, Kadio A. Typical aspects of neuromeningeal cryptococcosis in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Med Mal Infect. 1994;24:580–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoufi S, Agoumi A, Seqat M. Cryptococcal neuromeningitis in immunosuppressed subjects at Rabat University Hospital (Morroco) Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2008;66:79–81. doi: 10.1684/abc.2007.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sow PS, Diop BM, Dieng Y, Dia NM, Seydi M, Dieng T, et al. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis and HIV in Dakar, Senegal. Med Mal Infect. 1998;28:511–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oumar AA, Dao S, Ba M, Poudiougou B, Diallo A. Epidemiological, clinical and prognostic aspects of cryptococcal meningitis in Bamako university hospital, Mali. Rev Med Brux. 2008;29:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balogou AA, Volley KA, Belo M, Amouzou MK, Apetse K, Kombate D, et al. Mortality among HIV positive patients in the neurology service of the campus university hospital of Lomé, Togo. AJNS. 2007;26:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–30. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodasing N, Seaton RA, Shankland GS, Kennedy D. Cryptococcus neoformans var. Gattii meningitis in an HIV-positive patient: First observation in the United Kingdom. J Infect. 2004;49:253–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soumare M, Seydi M, Ndour CT, Dieng Y, Diouf AM, Diop BM. Current aspects of neuromeningeal cryptococcosis in Dakar, Senegal. Med Trop. 2005;65:559–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogaerts J, Rouvroy D, Taelman H, Kagame A, Aziz MA, Swinne D, et al. AIDS-associated to cryptococcal meningitis in Rwanda (1983-1992): epidemiologic and diagnostic features. J Infect. 1999;39:32–7. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(99)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.French N, Gray K, Watera C. Cryptococcal infection in a cohort of HIV-1-infectecd Ugandan adults. AIDS. 2002;16:1031–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisenge PR, Hawkins AT, Maro VP, Michele JP, Swai NS, Mueller A, et al. Low CD4 count plus coma predicts cryptococcal meningitis in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okome-Nkoumou M, Mbounja-Loclo ME, Kombila M. Panorama of opportunistic infections in the course of HIV infection in Libreville, Gabon. Cahiers Santé. 2000;3:329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohoue Petmy J, Ekobo AS, Ongolo SA. AIDS and cryptococcosis in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Med Mal Infect. 1992;22:30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woldemanuel Y, Haile T. Cryptococcosis in patients from Tikur Anbessa hospital, Addis-Abeba, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2001;39:185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soumaré M, Seydi M, Ndour CT, Fall N, Dieng Y, Sow AI, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and etiological features of neuromeningeal cryptococcosis at the Infectious Diseases Clinic of Fann Hospital, Dakar (Senegal) Med Mal Infect. 2005;35:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eholie SP, Ngbocho L, Bissagnene E, Coulibaly M, Ehni E, Kra O, et al. Deep mycosis during AIDS in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Bull Soc Path Ex. 1997;90:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisson GP, Lukes J, Thakur R, Mtoni I, MacGregor RR. Cryptococcus and lymphocytic meningitis in Botswana. S Afr Med J. 2008;98:724–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linden P, Pasculle AW, Kramen DJ, Kusne S, Manez R, Montecalvo MA, et al. Isolation of a nutritionally aberrant chain of Cryptococcus from a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1512–3. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botha RJ, Wessels E. Cryptococcal meningitis in an HIV negative patient with systemic sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:928–30. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.12.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bretaudeau K, Eloy O, Richer A, Bruneel F, Scott-Algara D, Lortholary O, et al. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis in an appearance immunocompetent subject. Rev Neurol. 2006;162:233–7. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(06)75005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndiaye M, Soumaré M, Mapoure YN, Seydi M, Sène-Diouf F, Ngom NF, et al. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis in an appearance none immunocompromised subject: A study about 3 cases in Dakar, Senegal. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2008;101:311–3. doi: 10.3185/pathexo3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millogo A, Ki-Zerbo GA, Andonaba JB, Lankoande D, Sawadogo A, Yameogo I, et al. Neuromeningeal cryptococcosis and HIV infection in the hospital of Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso) Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2004;97:119–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laroche R, Dupond B, Touze JP, Taelman H, Bogaerts J, Kadio A, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in African patients: Treatment with fluconazole. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:71–8. doi: 10.1080/02681219280000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soumare M, Seydi M, Ndour CT, Dieng Y, Ngom-Faye NF, Fall N, et al. Clear-fluid meningitis in HIV-infected patients in Dakar, Senegal. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2005;98:104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soumare M, Seydi M, Ndour CT, Dieng Y, Diouf AM, Diop BM. Update on neuromeningeal cryptococcosis in Dakar, Senegal. Med Trop. 2005;65:559–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collett G, Parrish A. Fluconazole donation and outcomes assessment in cryptococcal meningitis. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:175–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandes OF, Costa T, Costa MR, Soares AJ, Pereia AJ, Silva M. Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from patient with AIDS. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:75–8. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822000000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bii CC, Makimura K, Abe S, Taguchi H, Mugasia OM, Revathi G, et al. Antifungal drug and susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans from clinical sources in Nairobi, Kenya. Mycoses. 2007;50:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longley N, Muzoora C, Taseera K, Mwesigye J, Rwebembera J, Chakera A, et al. Dose response effect of high-dose fluconazole for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in southwestern Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1556–61. doi: 10.1086/593194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]