Abstract

Case series

Patient: Male, 11 • Female, 49

Final Diagnosis: Small fiber neuropathy

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Skin biopsy

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Prior autopsy reports demonstrate glycogen deposition in Schwann cells of the peripheral nerves in patients with infantile and late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD), but little is known about associated clinical features.

Case Report:

Here, we report the first confirmed cases of small-fiber neuropathy (SFN) in LOPD and present the results of a first attempt at screening for SFN in this patient population.

After confirming small-fiber neuropathy in 2 LOPD patients, 44 consecutive Pompe patients (iOPD=7, LOPD n=37) presenting to the Duke University Glycogen Storage Disease Program between September 2013 and November 2014 were asked to complete the 21-item Small-Fiber Neuropathy Screening List (SFNSL), where a score of ≥11 is considered to be a positive screen.

Fifty percent of patients had a positive SFN screen (mean score 11.6, 95% CI 9.0–14.2). A modest correlation between the SFNSL score and current age was seen (r=0.38, p=0.01), along with a correlation with duration of ERT (r=0.31, p=0.0495). Trends toward correlation with forced vital capacity and age at diagnosis were also present. Women had a higher mean SFNSL score (14.2) than men (8.2, p=0.017).

Conclusions:

SFN may occur in association with Pompe disease and precede the diagnosis. Further studies are needed to determine its true prevalence and impact.

MeSH Keywords: Erythromelalgia, Glycogen Storage Disease Type II, Polyneuropathies

Background

Late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD), initially recognized in the 1960’s, continues to be a disease with an emerging pheno-type, due to a partial deficiency of acid α-glucosidase (GAA). In contrast, classic infantile Pompe disease was long seen as characterized by cardiomyopathy, respiratory failure, and proximal muscle weakness leading to death within the first 2 years of life [1,2]. The advent of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) has lead to close monitoring of patients with both infantile Pompe and LOPD that did not occur in the past. Over the last 10 years, cardiac involvement (3–5) ptosis (6–10), impaired gastrointestinal function [11], dysphagia, lingual weakness [12,13], and aneurysms [14–16] have all been reported in association with Pompe disease.

Little has been written about peripheral nerve involvement in infantile Pompe disease or LOPD. Prior autopsy reports describe the presence of small, but numerous glycogen deposits in the Schwann cells surrounding both myelinated and unmyelinated axons [17,18]. Despite these findings, definitive clinical evidence of peripheral nerve involvement has not been reported in LOPD. A series of 17 patients undergoing electro-diagnostic testing revealed 4 patients with abnormalities on nerve conduction studies (NCS), but all could be attributed to a reduction in motor amplitudes secondary to the underlying myopathy [19]. A single case report described the occurrence of “severe chronic motor axonal peripheral neuropathy” in a patient with infantile-onset Pompe disease [20]. There were no abnormalities in sensory nerve responses and as previously stated, low motor amplitudes may arise from advanced myopathy or motor neuron disease. A study in mice did reveal that a component of motor neuron involvement contributed to diaphragmatic dysfunction [21]. As with many other aspects of this disease, this lack of evidence may be the result of under-reporting in a condition where respiratory failure and wheel chair dependence are of paramount concern. With advent of ERT, patients are living longer and becoming more concerned with quality of life. Given these factors, peripheral nerve involvement may become a more prevalent issue.

Small-fiber neuropathy (SFN) affects thinly myelinated and unmyelinated nerves that are primarily responsible for pain and temperature sensation. When affected by disease, patients often present with painful paresthesias in the extremities while nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) remain normal [22]. Autonomic dysfunction may also be present, causing a variety of symptoms that include orthostasis, gastrointestinal dysfunction, dry eyes and sexual dysfunction [22]. More recently, muscle cramps have been linked with SFN [23]. The diagnosis is complicated by lack of a clear gold standard for diagnosis. Recently, epidermal nerve fiber density counts obtained through skin biopsy have been touted as a potential standard [24], but the technique is invasive and costly.

In this study, we report two cases of skin biopsy confirmed SFN in patients with LOPD, along with a prospective study screening our clinic population for SFN. To our knowledge, these are the first reported occurrences of SFN in Pompe disease.

Case Report

The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study and all patients signed informed consent to participate in this study.

The two cases described came to attention through routine clinical care. These cases spurred the investigators to develop a prospective trial for all consecutive patients presenting to the Duke University Pompe Disease Clinic from September 2013-November 2014. A total of 44 patients with infantile Pompe (n=7) and LOPD (n=37) were screened and all agreed to participate. All patients completed the study.

Patients were given a printed copy of the Small-Fiber Neuropathy Screening List (SFNSL) for completion at the beginning of their clinic visit (Supplementary File). The SFNSL is a 21 question screening tool developed and validated for use in patients with sarcoidosis [25]. Like Pompe disease, sarcoidosis may cause muscular disease. This is relevant as some SFN and muscle symptoms may overlap. Adult patients completed the SFNSL unassisted, while the seven children completed this screening questionnaire with the assistance of a parent. The SFNSL was chosen due to its high sensitivity in detecting SFN, ease of administration and lack of discomfort for patients. The SFNSL consists of 2 parts, consisting of 8 and 13 questions respectively. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 4 as outlined by Hoitsma et al. 2011 [25]. A score of 11 or more carries 100% sensitivity and 31% specificity for SFN, while a score of >47 is 100% specific and 19% sensitive.

Patients completed this without assistance and returned it to SA, a genetic counselor who works in the clinic. The screening list was then scored by another investigator (LHW), who was not present at the clinic visit and had no direct contact with the patient. A cut-off score of 11 was used as recommended in the SFNSL validation study. A retrospective chart review was performed, collecting demographic information for each patient, including age, sex, age at first symptoms, age at diagnosis of LOPD, current therapy with ERT, duration of ERT, upright forced vital capacity (FVC) measures, presence of diabetes mellitus, other endocrine issues such as thyroid disease and any history of large fiber polyneuropathy. This review also collected information on strength of shoulder abduction and hip flexion was measured by a physical therapist recorded on the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. Information on the sensory examination was not included in the analysis, as it had not been performed systematically. No prospective testing was performed on this population and all prior testing had been performed as part of each patient’s routine clinical care.

The data collected was then entered into a Microsoft Excel database and then analyzed using JMP-11 (SAS, Inc. Cary, North Carolina). Descriptive statistics were calculated, including means, standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals. After ensuring that data was normally distributed, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to test for relationships between the SFNSL score and patient characteristics. The level of significance was set at 0.05 for all analysis.

Results

Patient 1

Patient 1 was an 11-year-old Caucasian boy who was diagnosed with Pompe disease at age 7 years. His family noticed easy fatigability and sought medical care. Creatine kinase levels were elevated and a muscle biopsy demonstrated myopathy. A dried blot spot test for Pompe disease screening was positive. The diagnosis was confirmed by genetic testing revealing GAA mutations associated with late-onset disease (c.-32-13T>G and c.1437+2T>C). He initiated ERT soon after his diagnosis and was stable in regards to muscle strength. His upright FVC was 95% and an echocardiogram was normal. He had no other medical conditions aside from a diagnosis of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, but was taking no medications for this.

The patient had experienced burning and tingling in the tips of all fingers and toes since age 7, prior to starting ERT. The pain was described as constant, but worsened by heat or exercise. He would wet his hands and feet to alleviate the sensation. Upon questioning, he was noted to have intermittent bradycardia, stomachaches, unexplained episodes of vomiting and a past history of urinary incontinence. There was no history of orthostatic hypotension or fainting. Distal sensory loss was found on the physical examination. Polyneuropathy was suspected, but NCS and EMG were normal. Extensive laboratory and immunologic tests did not reveal a cause.

A skin biopsy was performed, revealing frequent swellings of the epidermal nerve fibers, consistent with axonal degeneration. Nerve fiber density was 316 neurites/mm2 of skin. No normal values were available for this age group, but an extrapolation of normal values from teenagers yielded an expected normal range of 400–600 neurites/mm2 of skin. Quantitative sweat testing was performed, demonstrating reduced sweat production from the forearm, proximal leg, distal leg, hand and foot sites. Heart rate variability testing, tilt table testing and blood pressure response to the Valsalva maneuver were normal.

The patient was diagnosed with SFN based upon these findings. He failed gabapentin therapy, which seemed to cause headaches, anger and depression. He started pregabalin with some relief, but had difficulties with compliance. He now describes his dysesthesias as itching and burning, often interfering with sleep. His current SFNSL score is 29.

Patient 2

Patient 2 was a 49-year-old Caucasian woman diagnosed with LOPD by muscle biopsy, dried blood spot testing and genetic testing earlier the same year. Her mutations were identified as c.-32-13T>G (commonly observed in patients with late-onset Pompe disease) and c.525delT (previously reported and in vivo studies show no enzyme activity). At age 19 years, she had elevated liver enzymes and underwent liver biopsy with a diagnosis of fatty liver, despite having normal body habitus. She felt well and no additional evaluation was pursued. At age 41 years, she noted burning pains in her feet. Examinations document loss of pinprick sensation in the distal lower extremities at that time. She was diagnosed with SFN on the basis of her clinical presentation.

Patient 2 underwent skin biopsy for her suspected SFN, after nerve conduction studies and electromyography were normal. This was abnormal on 2 occasions; the most recent demonstrating advanced loss of epidermal nerve fiber density at age 47. With the second biopsy, no intra-epidermal nerve fibers were present at the distal calf site. Diagnostic evaluation (serum protein electrophoresis, immunofixation, 3-hour glucose tolerance testing, vitamin B-12, and inflammatory markers) for an underlying cause was negative and she was diagnosed with idiopathic SFN. Nerve conduction studies continued to show an absence of large fiber involvement at age 48 years.

This patient began to notice muscle weakness at age 45 years with difficulty climbing stairs. The weakness progressed to the point that she was unable to arise from the floor without assistance. An extensive evaluation for causes of myopathy was performed, culminating with the diagnosis of LOPD 4 years later. She presented to our clinic at this time to discuss initiation of ERT.

SFNSL Results

Forty-four other consecutive infantile Pompe and LOPD patients were identified for participation (Table 1). The group was composed of 19 males and 25 females with a mean age of 44.2±20 years. The mean age at diagnosis was 36.0±20 years. Seven patients with infantile Pompe disease were included with a mean age of 8.7 years. Excluding them from analysis did not result in any significant changes other than reducing the mean age and mean age of diagnosis. All but four of 44 patients were receiving ERT. The adults on ERT were receiving a standard dose of 20 mg/kg every 2 weeks with the mean duration of therapy being 4.6±3 years. The infantile-onset Pompe patients received ERT in doses ranging from 40 mg/kg every other week to 40 mg/kg weekly. The mean upright FVC was 64.0±20%. The mean MRC for shoulder abduction was 4.4 (range 2–5) and the mean for hip flexion was 3.3 (range 2–5). One patient had known diabetes mellitus, but no patient had a prior diagnosis of large fiber polyneuropathy. Within the 12 months preceding the study, only 7 of 44 patients had NCS performed at Duke University. These seven studies demonstrated no evidence of large fiber polyneuropathy.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 44 Pompe patients completing the SFNSL.

| Age (years) | 44.2±20 |

| Men | 19 (43%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 36.0±20 |

| Duration of ERT therapy (years) | 5.4±3 |

| Mean Total SFNSL score | 11.6±9 (95% CI 9.0–14.2) |

| % FVC (upright) | 64.0±20 |

| Shoulder abduction (MRC scale) | 4.4 |

| Hip flexion (MRC scale) | 3.3 |

ERT – enzyme replacement therapy; SFNSL – small fiber neuropathy screening list; %FVC – forced vital capacity; MRC – Medical Research Council.

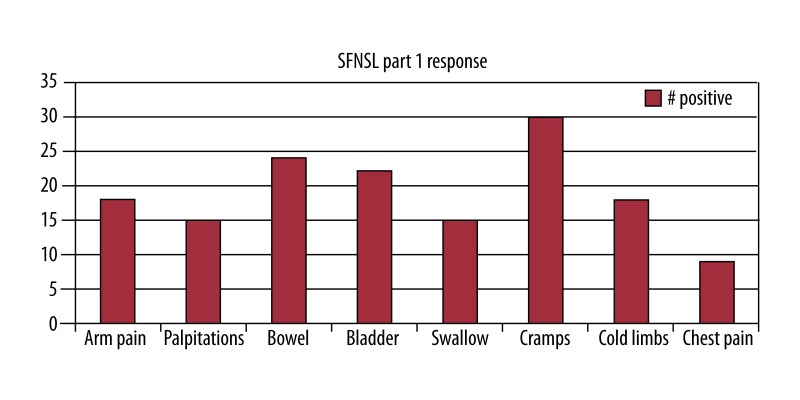

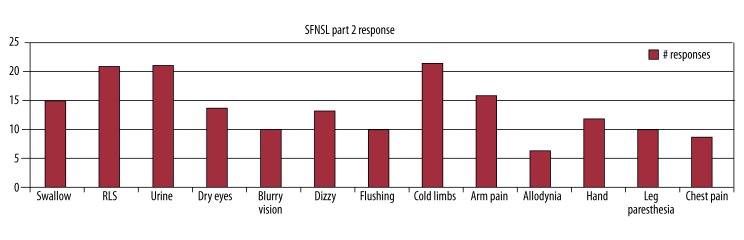

Twenty-two of 44 patients (50%) had a SFNSL score of ≥11, with the mean for the entire group being 11.6 (95% CI 9.0–14.2). In part 1, the mean score was 5.0. For part 2 of the questionnaire, the mean score was 6.6. Figures 1 and 2 provide detailed information on the number of patients who answered positively to each item on the questionnaire. Prior to screening, the presence of swallowing dysfunction on the questionnaire was of concern, as this might reflect bulbar muscle dysfunction as opposed to SFN. However, for part 1, only 34% of patients scored this item and only 2 scored the severity as more than mild. In part 2, only 15 of the patients again answered positively regarding swallowing difficulties, so it should not have had a significant effect upon the overall outcome.

Figure 1.

Results of the SFNSL Part 1 with 44 patients completing.

Figure 2.

Results of SFNSL Part 2 with 44 patients completing.

Extrapolating the numbers from the original SFNSL study, at least one-third of patients with a score of ≥11 would be expected to have SFN confirmed by skin biopsy with epidermal nerve fiber density counts. In this group, this estimate would include 7 of the 22 patients scoring ≥11, with those patients scoring >20 (n=7) being much more likely to have SFN confirmed by further testing.

Relationship with demographic characteristics

A modest correlation between the SFNSL score and current age was seen (r=0.38, p=0.01), along with a correlation with duration of ERT (r=0.31, p=0.0495). There were trends toward significant correlation with age at diagnosis (r=0.27, p=0.0795) and upright FVC (r=–0.26, p=0.09). There was no correlation between the total SFNSL score and shoulder abduction or hip flexor strength.

Differences between men and women

The mean SFNSL score was significantly higher in women (14.2, 95% CI 10.7–17.8) than in men (8.2, 95% CI 5.0–11.5, p=0.01). There was no difference in age between the two groups with a mean age of 39.2 years in men and 49.7 years in women (p=0.23), although there was a trend toward the women being older. There was no significant difference in duration of ERT (men 5.2 years, women 5.6 years, p=0.48) or the upright FVC% (65% men, 63% women, p=0.73). There was no significant difference in shoulder abduction (4.4 men, 4.3 women, p=0.68), but hip flexion strength was better in men (3.6 in men, 3.0 in women, p=0.017)

Discussion

SFN is not recognized as part of the Pompe phenotype. Here, we describe an 11-year-old boy and 49-year-old woman with LOPD who developed SFN without another recognized etiology. In both cases, symptoms of SFN began around the same time as muscle weakness became apparent. Patient 1’s diagnosis was confirmed at age 11 through skin biopsy and quantitative sweat testing, while Patient 2 was diagnosed at age 41 years through skin biopsy and clinical presentation. Given prior histologic reports showing glycogen deposition in the Schwann cells of peripheral nerves and anecdotal patient reports of limb pain and changes in heart rate, these cases prompted consideration of Pompe disease as a potential cause of SFN [17,18]. Subsequent screening of 44 consecutive clinic patients using the SFNSL 21 item questionnaire revealed 50% to be at risk for SFN. This is in line with mounting clinical evidence suggesting neuropathic involvement in Pompe disease [17–20].

There were modest correlations between current age (r=0.38, p=0.01), duration of ERT (r=0.31, p=0.0495), and the SFNSL score. This suggests that the accumulating burden of disease plays a role in the expression of the symptoms queried on the SFNSL, but certainly does not explain all findings. For the index cases reported, the SFN symptoms began early in the disease course and were severe enough to warrant an extensive evaluation. Further studies on SFN in Pompe disease will need to consider other factors, including the role that differing genetic mutations play in the resulting clinical phenotype.

The current study is not without limitations, but is meant as an exploratory screening to determine if further work on SFN in Pompe disease is needed. The small sample size (n=44) is a primary issue, and as the study utilized retrospective chart review, standardized assessment of sensation and detailed NCS/EMG were not available. A larger limitation is the lack of a widely accepted screening questionnaire for SFN. The questionnaire used was validated for sarcoidosis, not Pompe disease, but it was one of the few non-invasive screening lists available for non-diabetic SFN.

If present, identification of SFN would be important in patient care. In addition to the morbidity that arises from neuropathic pain, the presence of SFN would alert physicians to the possibility of associated autonomic dysfunction. Larger, well-formulated studies are needed to determine the true incidence of SFN in Pompe disease and its relationship with patient-reported pain and other symptoms. In the current cohort, we are planning skin biopsies of all consenting patients with an SFNSL score of ≥11 to establish the presence or absence of small-fiber neuropathy. These intraepidermal nerve fiber density measures are essential, as the SFNSL must be validated for infantile Pompe and LOPD and revised as necessary.

Conclusions

SFN can occur in Pompe disease and precede disease diagnosis. Clinicians should be vigilant for symptoms of SFN when treating patients with Pompe disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

P.S. Kishnani reports receiving research and grant support as well as honoraria and consulting fees from Genzyme, A Sanofi Company. P.S. Kishnani is a member of the Pompe Disease and the Gaucher Disease Registry Advisory Boards for Genzyme, A Sanofi Company.

References:

- 1.Engel AG, Hirschhorn R. Acid Maltase Deficiency. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. 2. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 1559–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kishnani PS, Steiner RD, Bali D, et al. Pompe disease diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med. 2006;8(5):267–88. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000218152.87434.f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Beek NA, Soliman OI, van Capelle CI, et al. Cardiac evaluation in children and adults with Pompe disease sharing the common c.-32-13T>G genotype rarely reveals abnormalities. J Neurol Sci. 2008;275(1–2):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soliman OI, van der Beek NA, van Doorn PA, et al. Cardiac involvement in adults with Pompe disease. J Intern Med. 2008;264(4):333–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller-Felber W, Horvath R, Gempel K, et al. Late onset Pompe disease: clinical and neurophysiological spectrum of 38 patients including long-term follow-up in 18 patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(9–10):698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slingerland NW, Polling JR, van Gelder CM, et al. Ptosis, extraocular motility disorder, and myopia as features of pompe disease. Orbit. 2011;30(2):111–13. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2010.546932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravaglia S, Bini P, Garaghani KS, Danesino C. Ptosis in Pompe disease: common genetic background in infantile and adult series. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30(4):389–90. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181f9a923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravaglia S, Repetto A, De Filippi P, Danesino C. Ptosis as a feature of late-onset glycogenosis type II. Neurology. 2007;69(1):116. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000270101.95790.fb. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanovitch TL, Banugaria SG, Proia AD, Kishnani PS. Clinical and histologic ocular findings in pompe disease. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47(1):34–40. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20100106-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanovitch TL, Casey R, Banugaria SG, Kishnani PS. Improvement of bilateral ptosis on higher dose enzyme replacement therapy in Pompe disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30(2):165–66. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181ce162a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein DL, Bialer MG, Mehta L, Desnick RJ. Pompe disease: dramatic improvement in gastrointestinal function following enzyme replacement therapy. A report of three later-onset patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101(2–3):130–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubrovsky A, Corderi J, Lin M, et al. Expanding the phenotype of late-onset pompe disease: Tongue weakness: A new clinical observation. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(6):897–901. doi: 10.1002/mus.22202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobson-Webb LD, Jones HN, Kishnani PS. Oropharyngeal dysphagia may occur in late-onset Pompe disease, implicating bulbar muscle involvement. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013;23(4):319–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Gharbawy AH, Bhat G, Murillo JE, et al. Expanding the clinical spectrum of late-onset Pompe disease: dilated arteriopathy involving the thoracic aorta, a novel vascular phenotype uncovered. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103(4):362–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kretzschmar HA, Wagner H, Hubner G, et al. Aneurysms and vacuolar degeneration of cerebral arteries in late-onset acid maltase deficiency. J Neurol Sci. 1990;98(2–3):169–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90258-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacconi S, Bocquet JD, Chanalet S, et al. Abnormalities of cerebral arteries are frequent in patients with late-onset Pompe disease. J Neurol. 2010;257(10):1730–33. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiMauro S, Stern LZ, Mehler M, et al. Adult-onset acid maltase deficiency: a postmortem study. Muscle Nerve. 1978;1(1):27–36. doi: 10.1002/mus.880010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobson-Webb LD, Proia AD, Thurberg BL, et al. Autopsy findings in late-onset Pompe disease: A case report and systematic review of the literature. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106(4):462–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobson-Webb LD, Dearmey S, Kishnani PS. The clinical and electrodiagnostic characteristics of Pompe disease with post-enzyme replacement therapy findings. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122(11):2312–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burrow TA, Bailey LA, Kinnett DG, Hopkin RJ. Acute progression of neuromuscular findings in infantile Pompe disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;42(6):455–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeRuisseau LR, Fuller DD, Qiu K, et al. Neural deficits contribute to respiratory insufficiency in Pompe disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(23):9419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902534106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26(2):173–88. doi: 10.1002/mus.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopate G, Streif E, Harms M, et al. Cramps and small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(2):252–55. doi: 10.1002/mus.23757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(7):903–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoitsma E, De Vries J, Drent M. The small fiber neuropathy screening list: Construction and cross-validation in sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]