Abstract

Pathological arterial wall changes have been cited as potential mechanisms of cerebrovascular disease in the HIV population. We hypothesize that dilatation would be present in arterial walls of patients with HIV compared to controls. Fifty-one intracranial arteries, obtained from autopsies of five individuals with HIV infection and 13 without, were fixed, embedded, stained, and digitally photographed. Cross-sectional areas of intima, media, adventitia and lumen were measured by preset color thresholding. A measure of arterial remodeling was obtained by calculating the ratio between the lumen diameter and the thickness of the arterial wall. Higher numbers indicate arterial dilatation, while lower numbers indicate arterial narrowing. HIV-infected brain donors were more frequently black (80% vs. 15%, P = 0.02) compared with uninfected donors. Inter and intra-reader agreement measures were excellent. The continuous measure of vascular remodeling was significantly higher in the arteries from HIV donors (β = 2.8, P = 0.02). Adjustments for demographics and clinical covariates strengthen this association (β = 9.3, P = 0.01). We found an association of HIV infection with outward brain arterial remodeling. This association might be mediated by a thinner media layer. The reproduction of these results and the implications of this proposed pathophysiology merits further study.

Keywords: arterial layers, arterial remodeling, dolichoectasia, HIV, stroke

Introduction

Effective antiviral therapies have significantly prolonged the life expectancy of HIV-infected individuals. However, as mortality from opportunistic infections has dramatically dropped, the incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular disease in patients with HIV have steadily increased, and now exceed rates among uninfected individuals of the same age.1 Multiple explanations have been proposed. The most widely accepted is that antiretroviral therapies (ART), particularly protease inhibitors, change lipid metabolism.2 Other explanations include an increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and direct effects of HIV on blood vessels.3,4

An association between HIV infection and cerebrovascular disease risk remains more elusive, although a few epidemiological studies suggest that HIV might increase the risk of stroke and stroke-related hospitalization.5 Proposed mechanisms of stroke in HIV infection include opportunistic infections of the CNS, hypercoagulability secondary to neoplasms, atherosclerotic disease and HIV vasculopathy, among others.5–7 In a previous autopsy study of cerebral arteries from patients without stroke, we found that the media (i.e. muscularis) layer from patients with HIV was thinner than in uninfected young controls and hypothesized that this represented a preclinical stage in the development of HIV vasculopathy, a condition characterized by dilatation and increased tortuosity of the intra- and extracranial arteries similar to that observed in patients with dolichoectasia, a form of outward vascular remodeling.8–10 No study to date has evaluated the type of vascular remodeling occurring in HIV-infected patients. Understanding the pathophysiology of HIV effects on blood vessels may lead to ways to curb the rising cardiovascular and cerebrovascular burden in this population.

The goal of this pathology report is to test the hypothesis that HIV infection is associated with dilatation of the intracranial arteries.

Materials and Methods

Post mortem tissues from individuals with or without HIV infection were obtained from the University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank.10 Arteries were dissected from formalin-fixed brain according to standard anatomical landmarks. Clinical data were obtained from the donor registry, medical records and autopsy reports when available. HIV status was evaluated by antibody screen assay, ELISA and Western blot, done in conjunction with the University of Miami Bone and Tissue Bank, which also supplied demographic data, including sex, age, race, height, body weight, brain weight, causes of death, clinical risk factors, and cocaine abuse if applicable, in these cases. Written informed consent was obtained from donors prior to death and from the next-of-kin after death.

Data collection and processing

The arteries were embedded in paraffin and cut transversely at a thickness of 5 μm at the Pathology Research Resources, Histology Laboratory of the University of Miami. HE stains were used to determine the presence of adventitial lymphocytes. The van Gieson stains were scored for the presence of gaps and duplications of the internal elastic lamina (IEL). All stained sections were digitally photographed on the same microscope, with constant illumination, magnification and scale (3.7 μm/pixel).

The morphometric features of the arterial walls were measured in the digital images with open-source ImageJ software (WS Rasband, ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, imagej.nih. gov/ij/, 1997–2011). First, the arterial layers were segmented by pre-defined color intensity-based thresholding. If needed, manual correction was used to refine the segmentation. The outer perimeter of the adventitia and the areas of each arterial layer were measured. The area measurements obtained were multiplied by 1.25 and the perimeter by 1.12, an approximate correction factor for the shrinkage occurring during fixation, dehydration and paraffin embedding.11,12 The arterial walls deform during preparation and embedding due to the lack of luminal material that holds its original tubular shape. We assumed that the arteries, when filled with blood, are tubular structures with an approximately circular perimeter (i.e. circumference). Based on this assumption, we derived the expected total arterial cross-sectional area from the measured outer adventitial perimeter. From this calculated area, we subtracted the arterial wall cross-sectional area (the sum of the cross-sectional areas of the adventitia, media and intima) to obtain the cross-sectional area of the lumen, the diameter of which was calculated from the circumference, assuming circularity. Due to the diversity of arterial sizes included in the sample, we expressed the cross-sectional areas of each arterial layer as a proportion of the total wall area and the lumen as a proportion of the total arterial area to enable comparisons. Arterial stenosis was calculated by dividing the intima area by the IEL area and then multiplied by 100.13 The intra- and inter-reader agreement for the segmentation measures was obtained by comparing the repeated measurements in a 30% random sample of the arteries included. Both operators (JG and DYC) were blinded to the HIV status. The reproducibility of the IEL disruption, IEL duplication and adventitia lymphocytic infiltrate has been previously confirmed.10

Variable definition

Disruption of the IEL was defined as a gap in the IEL continuity. Duplication of the IEL was defined as the presence of one or more IEL. Adventitial lymphocytic cells were defined as lymphocytes present in the adventitia. Cross-sectional bias was attributed to the lack of apparent uniformity in the thickness of the adventitia and muscularis layer. The proportions of each arterial layer and the lumen were used as continuous variables. Vascular remodeling was defined as the ratio of the lumen diameter to the wall thickness. Higher numbers imply outward vascular remodeling or dilatation while smaller numbers suggest inward vascular remodeling or narrowing.

Statistical analysis

For statistical significance in proportion and means differences, χ2 or t-test was used as appropriate. The predicted (i.e. dependent) variable was the wall-to-lumen ratio. Normality was assessed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov Lilliefors test. Since the arteries from the same individual are not independent among themselves, we used a multilevel mixed model to account for correlations among clusters of arteries.14 We used five models to assess the relationship of HIV and wall-to-lumen ratio: Model 0: univariate analysis; Model 1: controlling for age, sex and race; Model 2: Model 1 plus hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and cocaine use; Model 3: Model 2 plus IEL gaps, IEL duplication, adventitia inflammatory cells, posterior versus anterior circulation and brain weight; and Model 4: Model 3 plus media and adventitia proportion. An alpha value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Type III effects were used to evaluate significance. Agreement between measurements was evaluated with kappa value for categories and with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for continuous variables. The analysis was carried out with SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

We analyzed intracranial arteries from five brain donors with HIV and 13 without HIV. Although the numbers were small, the HIV brain donors were younger (45 vs. 59 years, P = 0.23), more frequently men (80% vs. 46%, P = 0.21) and more frequently black (80% vs. 15%, P = 0.02). No patient with HIV had a recorded history of hypertension, dyslipidemia or ART at the time of death. Only one patient with HIV had diabetes. The proportion of cocaine abuse was similar in both groups (20% vs. 38%, P = 0.46). The most common cause of death in both groups was ischemic cardiomyopathy, and the second most common was infection.

Fifty-one arteries were collected from the 18 brains and included in this analysis (Table 1): 14 middle cerebral arteries (MCA), 12 basilar arteries (BA), 10 intracranial internal carotid arteries (ICA), nine vertebral arteries (VA), three posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) and three anterior cerebral arteries (ACA). The HIV group was represented by 15 arteries and the non-HIV group by 38 arteries. The proportion of posterior versus anterior circulation arteries was similar in both groups (48% vs. 66% anterior vessels, P = 0.23). Two arteries were excluded from the non-HIV group due to extreme pathology manifested by mineralization of the complete intima almost fully obliterating the lumen. The general characteristics of the arteries initially evaluated are reported in Table 1. The PCA and the posterior communicating artery were excluded from further analysis due to obvious differences in their morphometric values. The inter- and intra-operator reliability was excellent for the measurements of the outer adventitial perimeter as well as for each individual arterial layers areas (ICC > 0.99).

Table 1.

Arterial morphometric measurements in the studied sample

| Artery (n) | Outer circumference mm ± SD |

Interadventitial diameter mm ± SD |

Lumen diameter mm ± SD |

Arterial wall area mm2 ± SD |

Arterial wall thickness mm ± SD |

Media proportion % ± SD |

Intima proportion % ± SD |

Adventitia proportion % ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA (10) | 13.2 ± 1.3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 44.8 ± 6.4 | 16.1 ± 7.4 | 39.1 ± 10.6 |

| MCA (14) | 10.4 ± 3.6 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 42.3 ± 7.5 | 16.1 ± 5.8 | 41.5 ± 8.6 |

| ACA (3) | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 43.6 ± 3.5 | 14.4 ± 7.3 | 42.0 ± 10.8 |

| BA (12) | 11.9 ± 2.2 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 49.5 ± 8.3 | 13.3 ± 5.1 | 37.2 ± 7.8 |

| VA (9) | 10.4 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 46.6 ± 5.9 | 18.3 ± 7.0 | 35.1 ± 7.0 |

| PCA (3) | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 44.5 ± 9.9 | 11.8 ± 1.4 | 43.8 ± 11.4 |

| PICA (1) | 5.6 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.21 | 28.2 | 17.4 | 54.5 |

| PcommA (1) | 5.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.15 | 36.3 | 9.5 | 54.2 |

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; N, number; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; PcommA, posterior communicating artery; PICA, posterior inferior cerebellar artery; SD, standard deviation; VA, vertebral artery.

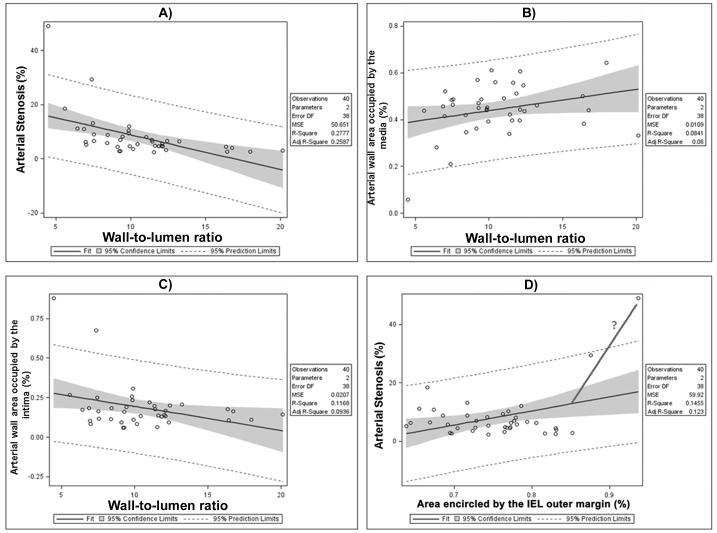

Arterial remodeling correlates in HIV-negative brains

The posterior circulation arteries had greater media proportions (4.0% thicker, P = 0.03) and thinner adventitia than the anterior circulation arteries (3.8% thinner, P = 0.08). On average, the ratio of wall to lumen was 11.7 ± 3.25, ranging from 5.6 to 20.5. In univariate analysis, Black race, hypertension and IEL duplication were the most important predictors of inward vascular remodeling, only black race being significant in multivariate analysis (P = 0.02, Table 2). Using the formula mentioned above, the more severe arterial stenosis in the sample was 19%. Brain weight was the most important predictor of outward vascular remodeling. In multivariate analysis, cocaine use and female sex had the greatest beta coefficient values but were not statistically associated with outward vascular remodeling. A thicker intima was associated with inward vascular remodeling (β = −0.4 per every 5% increment) while greater media proportions were associated with outward vascular remodeling (β = 0.5 per every 5% increment). None of these predictors reached statistical significance (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Brain arterial remodeling correlates in arteries from donors without HIV

| Univariate analysis β- coefficient (P-value) |

Multivariate analysis† β- coefficient (P-value) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (every 10 years) | −0.2 (0.55) | −0.2 (0.80) |

| Female sex | −0.9 (0.43) | 4.0 (0.06) |

| Black race | −2.6 (0.15) | −6.1 (0.02) |

| Hypertension | −1.5 (0.29) | 0.6 (0.79) |

| Dyslipidemia | −0.6 (0.69) | 0.3 (0.91) |

| Cocaine abuse | −0.3 (0.81) | 3.7 (0.13) |

| Brain weight (every 100 grams) | 0.9 (0.11) | 1.0 (0.17) |

| Posterior circulation | −0.4 (0.66) | −0.8 (0.39) |

| Adventitia inflammation | −0.9 (0.41) | −1.0 (0.25) |

| IEL gaps | −0.8 (0.56) | −0.5 (0.75) |

| IEL duplication | −2.6 (0.02) | −2.0 (0.15) |

| Intima (every 5% increase) | −0.5 (0.32) | −0.4 (0.38) |

| Media (every 5% increase) | 0.3 (0.36) | 0.5 (0.17) |

| Adventitia (every 5% increase) | 0.01 (0.93) | - |

A negative beta coefficient suggests inward arterial remodeling while a positive value suggests outward vascular remodeling.

Controlling for all variables including in the first column except for adventitia proportion due to redundancy with the intima and media proportion. IEL, internal elastic lamina.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of individual arterial wall components and lumen by wall thickness to lumen diameter ratio. 1A: This plot shows that greater degrees of stenosis correlate with lower lumen-to-wall ratio (LWR). 1B and 1C: A thinner media is associated with a lower LWR, probably a reflection of increased intima proportion within the arterial wall. 1D: While the degree of stenosis remains stable, there is a growing internal elastic lamina area (IEL). The more vertical line and the question mark indicate a potential increase in stenosis with no more IEL accommodation.

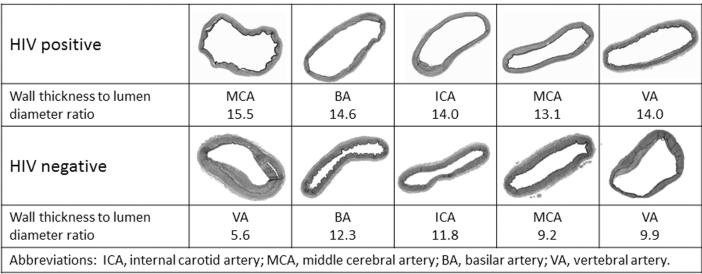

Contribution of HIV to intracranial arterial remodeling

Compared with the non-HIV group, brain arteries from donors with HIV had 1% thinner intima, 4.3% thinner media and 4.9% thicker adventitia. Only the media thickness showed a trend for significance (P = 0.09). Comparing the media thickness in the HIV group (n = 5) to the non-HIV group within the same age range (n = 7), HIV was associated with a decrease of 5.6% in the media thickness (P = 0.03). This difference was smaller when the older uninfected subjects are included in the comparison (3.6%, P = 0.30). Arteries from donors with HIV had on average 2% less arterial stenosis compared to uninfected controls, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.14). The arterial wall proportion was smaller and the lumen proportion larger in the HIV group compared with the uninfected group (β = 5.8, P = 0.02). Consequently, the continuous measure of arterial remodeling was significantly higher in the cerebral arteries from individuals with HIV (β = 2.8, P = 0.02, Fig. 2). Further adjustments for covariates strengthen this association (β = 9.3, P = 0.01, Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Examples of brain arterial remodeling by HIV status. It can be observed that brain arteries from HIV brain donors look thinner and more dilated that the HIV-negative controls.

Table 3.

Relationship between HIV infection and wall-to-lumen ratios (arterial remodeling)

| Model 0 (β- coefficient (P- value)) |

Model 1 (β- coefficient (P- value)) |

Model 2 (β- coefficient (P- value)) |

Model 3 (β- coefficient (P- value)) |

Model 4 (β- coefficient (P- value)) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV positive | 2.8 (0.02) | 4.4 (<0.006) | 6.3 (0.1) | 10.1 (0.006) | 9.3 (0.01) |

Model 0: Univariate analysis. Model 1: controlling for age, gender and race. Model 2: Model 1 plus hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and cocaine use. Model 3: Model 2 plus internal elastic lamina (IEL) gaps, IEL duplication, adventitia inflammatory cells, posterior versus. anterior circulation, and brain weight. Model 4: Model 3 plus media and adventitia proportion. A negative beta coefficient suggests inward arterial remodeling while a positive value suggests outward vascular remodeling.

Discussion

In this sample, HIV infection was associated with outward arterial remodeling, suggesting that in HIV, the cerebral arteries are susceptible to dilatation. This association was stronger after controlling for other factors that we found influenced vascular remodeling. Using a very reliable technique to quantify the arterial cross-sectional area, we confirmed a previous observation that the media thickness in patients with HIV is smaller than in uninfected controls.10 Controlling for media thickness did not change the strong association noted between HIV and outward vascular remodeling.

The clinical and pathophysiological implications of these findings are multiple, although they are not clearly proven. There are few studies reporting correlates of vascular remodeling in the brain, and even less is known about the meaning of arterial remodeling and the associated risk of cerebrovascular disease in HIV infection. It is possible that this strong dilatation tendency culminates in “HIV vasculopathy,” a pathological form of extra- and intracranial arterial dilatation and tortuosity often associated with stroke when cerebral arteries are involved.7,8,15 This form of arteriopathy has been described in 5–20% of patients with HIV who present with strokes, although difficulties with the definition and proper differential workup limit comparisons across studies.6,16 In our sample, none of the patients had a self-reported clinical stroke. We hypothesized that the tendency to dilate observed in the HIV group might be a preclinical stage in the development of arteriopathy and stroke; a longitudinal study is needed to test this hypothesis. Even more, the only significant alteration found in the composition of the arterial wall of HIV brain arteries was a thinner media, and controlling for it did not significantly affect the association. This finding is consistent with reports on HIV vasculopathy in intra and extracranial large arteries.15–17 Two autopsy reports from patients who had strokes associated with HIV vasculopathy have consistently demonstrated media fibrosis and IEL disruption in the involved arteries.16,17 Chetty et al. demonstrated media fibrosis and IEL degeneration in areas with the worst dilatation. In areas adjacent to the aneurysms, inflammation and angiogenesis with breakage of collagen was found.15 Direct smooth muscle cell infection by HIV could be the mechanism by which HIV leads to a thinner media.18 We think that HIV infection might be a key mediator in the weakening of the arterial wall and subsequent flow-induced outward remodeling. This hypothesis is supported by physiological and mechanical data showing that the resistance of the arteries to withstand blood flow is conferred mostly by the media, and that degeneration of the media is associated with arterial dilatation.19,20

Other mechanisms by which HIV can affect the arterial composition have been invoked. Proliferating endothelial cells can replicate HIV, particularly in the context of increased IL-1 and TNF-α exposure.21 Direct infection and activation of the endothelial cells might be an alternative explanation to the deleterious effects of HIV to the arterial wall, particularly in the context of severe immunosuppression.22–25 HIV-infected monocytes can be found within the arterial wall in atherosclerotic lesions and inflammatory vasculopathic changes.18,26,27 Whether the degree of inflammation or monocytic infiltration might play a role in the observed arterial changes reported here remains unknown. Adequate immunological characterization of inflammatory cells might help to answer this question. Contrary to what we found in the HIV subsample, in non-HIV arteries, a thicker media was positively associated with greater dilatation. Whether this represents a normal compensatory response to increasing diameter in the non-HIV population is unknown, but is certainly worth exploring. Another possible explanation to our findings is that the non-HIV control arteries used in this study were diseased. However, the normal aspect of some of the presented arteries in Figure 2 plus the relatively low degree of stenosis in the whole sample (no more than 20%) suggest that the control arteries are not severely diseased. Having had healthier controls with no history of IV drug use or cardiovascular risk factors would have been ideal.

The closest model of brain outward arterial remodeling in humans without HIV infection is dolichoectasia, a condition characterized by abnormal arterial dilatation and tortuosity. Although definitions of dolichoectasia vary, larger arterial diameters are associated with increased mortality and cerebrovascular events.26 In cross-sectional samples, it has been shown that the greater the arterial diameters, the greater the likelihood of association with stroke and other cardiovascular events, suggesting a dose–effect relationship between arterial diameters and pathological consequences.27,28 Plausible mechanisms mediating the increased risk of stroke include dampening of the blood flow with subsequent propensity to develop in situ thrombosis or artery-to-artery embolism, mechanical traction of small penetrating arteries, or intramural hemorrhage leading to acute lumen narrowing.29,30 In contrast to the apparent role of the media in HIV-induced outward remodeling, the starting point in the association between dolichoectasia and cardiovascular risk factors seems to be the intima.9 A healthy endothelium senses changes in wall shear stress and wall tension that activate a cascade of chemical signals that lead to accommodation of the flow to maintain a normal pressure.19,31,32 The lack of adequate adaptation leads to a fragmented IEL, a rather quiescent media and smooth muscle cells, and flow-induced irreversible dilatation.11,33 The scatter plots in Figure 1 show some trends in the relationship between each arterial layer and the overall wall-to-lumen ratio, but if these represent the true magnitude of the effects, this small study lacks statistical power to confirm them. The randomness of the reports and the lack of systematization in the dolichoectasia definition preclude a firm conclusion, but the results should encourage further studies to define whether outward vascular remodeling per se is pathologic or if it serves as a cluster for an overall unhealthy cardiovascular profile.

The emergence of vascular remodeling as a concept to explain the complex interaction between the flow mechanics and the arterial wall is not new, although it has been studied predominantly in extracranial arteries.13,31,34 Different methods have been used to describe remodeling but none has accounted for expected differences in arterial dimensions depending on body size dimension, particularly head size.35 Two important methods to study remodeling have been reported by Glagov et al.13 and Pasterkamp et al.34 Glagov’s method quantifies the percentage of stenosis and draws a scatter plot with the absolute lumen diameter using only the left descending coronary artery, which facilitated direct comparisons among participants.13 Correction for heart size differences among participants was not attempted. This method would have been inappropriate for our study due to the multiple arterial sizes included. Controlling for head size differences was not possible since we lack this information from autopsy reports. Pasterkamp’s method corrects for arterial diameter tapering to determine the expected lumen area and then a matching percentage between the measured versus the expected lumen area is obtained. This method requires at least two different sections from an arterial segment. Since we only obtained one cross-sectional cut, then this method was not suited for our study. Furthermore, it is unknown if the beta coefficient used to correct for arterial diameter tapering is the same in intracranial arteries, especially in the context of frequent branching points. The method used in our study has the advantage of controlling for arterial size differences within arteries and between individuals by using the proportion of each layer in the arterial wall and the proportion of the lumen out of the total arterial cross-sectional area. As shown in Figure 1, greater proportional lumens correlate perfectly with greater wall-to-lumen ratios and vice versa. Additional benefits of this proposed remodeling measure is that it is highly reliable, and that it expresses continuously a physiologically continuous process, increasing the power of the comparisons. There are several limitations inherent to our study. The study is underpowered to detect important associations with cardiovascular risk factors and other clinical variables that could have confounded the association of HIV and vascular remodeling, particularly nutritional state, immunological status, and ART administration or other associations suggested in Table 2. Based on our previous report from the same hospital from which the cases were obtained, it is likely that the majority of the HIV cases were not exposed to ART and that most of them had AIDS.36 Additionally, the equal distribution of adventitial inflammatory cells gives us some reassurance that at least the association between HIV and outward arterial remodeling was not mediated by acute vasculitis. The clinical information was collected from medical records, and in at least three cases, it was minimal. This is likely to introduce bias to under-report cardiovascular disease in patients with HIV and underestimate the effects that these factors have on the remodeling process. However, in the analysis of the non-HIV group, cardiovascular risk factors were not major determinants of remodeling. The sample studied is not representative of the general population; consequently, generalization is not possible. An adequately powered study with different or healthy controls is needed to confirm our results.

In conclusion, our results suggest a strong association of HIV infection with outward vascular remodeling in the studied sample. This association might be mediated by a thinner media layer, but other, unmeasured factors might play a role. If our findings are confirmed, they could lead to innovative ways to approach the rising incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in this population.

References

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dube MP, Lipshultz SE, Fichtenbaum CJ, Greenberg R, Schecter AD, Fisher SD. Effects of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy on the heart and vasculature. Circulation. 2008;118:e36–e40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currier JS, Lundgren JD, Carr A, et al. Epidemiological evidence for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients and relationship to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Circulation. 2008;118:e29–e35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole JW, Pinto AN, Hebel JR, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the risk of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:51–56. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000105393.57853.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor MD, Lammie GA, Bell JE, Warlow CP, Simmonds P, Brettle RD. Cerebral infarction in adult AIDS patients: observations from the Edinburgh HIV Autopsy Cohort. Stroke. 2000;31:2117–2126. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortiz G, Koch S, Romano JG, Forteza AM, Rabinstein AA. Mechanisms of ischemic stroke in HIV-infected patients. Neurology. 2007;68:1257–1261. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259515.45579.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutierrez J, Ortiz G. HIV/AIDS patients with HIV vasculopathy and VZV vasculitis : a case series. Clin Neuroradiol. 2011 Sep;21(3):145–51. doi: 10.1007/s00062-011-0087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez J, Sacco RL, Wright CB. Dolichoectasia-an evolving arterial disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:41–50. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez J, Glenn M, Isaacson R, Marr D, Mash D, Petito C. Thinning of the arterial media layer as a possible preclinical stage in HIV vasculopathy: a pilot study. Stroke. 2012 Apr;43(4):1156–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sho E, Nanjo H, Sho M, et al. Arterial enlargement, tortuosity, and intimal thickening in response to sequential exposure to high and low wall shear stress. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda H, Zhuang YJ, Singh TM, et al. Adaptive remodeling of internal elastic lamina and endothelial lining during flow-induced arterial enlargement. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2298–2307. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1371–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Littell RC, Pendergast J, Natarajan R. Modelling covariance structure in the analysis of repeated measures data. Stat Med. 2000;19:1793–1819. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20000715)19:13<1793::aid-sim482>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chetty R, Batitang S, Nair R. Large artery vasculopathy in HIV-positive patients: another vasculitic enigma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:374–379. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tipping B, de Villiers L, Wainwright H, Candy S, Bryer A. Stroke in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1320–1324. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.116103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubrovsky T, Curless R, Scott G, et al. Cerebral aneurysmal arteriopathy in childhood AIDS. Neurology. 1998;51:560–565. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eugenin EA, Morgello S, Klotman ME, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects human arterial smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro: implications for the pathogenesis of HIV-mediated vascular disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1100–1111. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoi Y, Gao L, Tremmel M, et al. In vivo assessment of rapid cerebrovascular morphological adaptation following acute blood flow increase. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:1141–1147. doi: 10.3171/JNS.2008.109.12.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasser TC, Ogden RW, Holzapfel GA. Hyperelastic modelling of arterial layers with distributed collagen fibre orientations. J R Soc Interface. 2006;3:15–35. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2005.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conaldi PG, Serra C, Dolei A, et al. Productive HIV-1 infection of human vascular endothelial cells requires cell proliferation and is stimulated by combined treatment with interleukin-1 beta plus tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Med Virol. 1995;47:355–363. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf K, Tsakiris DA, Weber R, Erb P, Battegay M. Antiretroviral therapy reduces markers of endothelial and coagulation activation in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:456–462. doi: 10.1086/338572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsue PY, Lo JC, Franklin A, et al. Progression of atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness in patients with HIV infection. Circulation. 2004;109:1603–1608. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124480.32233.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren Z, Yao Q, Chen C. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 120 increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression by human endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2002;82:245–255. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zietz C, Hotz B, Sturzl M, Rauch E, Penning R, Lohrs U. Aortic endothelium in HIV-1 infection: chronic injury, activation, and increased leukocyte adherence. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1887–1898. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passero SG, Rossi S. Natural history of vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Neurology. 2008;70:66–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000286947.89193.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pico F, Labreuche J, Gourfinkel-An I, Amarenco P. Basilar artery diameter and 5-year mortality in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2342–2347. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000236058.57880.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milandre L, Bonnefoi B, Pestre P, Pellissier JF, Grisoli F, Khalil R. Vertebrobasilar arterial dolichoectasia. Complications and prognosis) Rev Neurol (Paris) 1991;147:714–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon HM, Kim JH, Lim JS, Park JH, Lee SH, Lee YS. Basilar artery dolichoectasia is associated with paramedian pontine infarction. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:114–118. doi: 10.1159/000177917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakatomi H, Segawa H, Kurata A, et al. Clinicopathological study of intracranial fusiform and dolichoectatic aneurysms : insight on the mechanism of growth. Stroke. 2000;31:896–900. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ. The emerging concept of vascular remodeling. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1431–1438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heil M, Schaper W. Influence of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors on collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis) Circ Res. 2004;95:449–458. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141145.78900.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegedus K, Molnar P. Age-related changes in reticulin fibers and other connective tissue elements in the intima of the major intracranial arteries. Clin Neuropathol. 1989;8:92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasterkamp G, Schoneveld AH, van Wolferen W, et al. The impact of atherosclerotic arterial remodeling on percentage of luminal stenosis varies widely within the arterial system. A postmortem study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3057–3063. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutierrez J, Gardener H, Bagci A, et al. Dolichoectasia and intracranial arterial characteristics in a race-ethnically diverse community-based sample: the northern manhattan study. Stroke. 2011;42:e118. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutierrez J, Yoo C. Stroke prediction in a sample of HIV/AIDS patients: logistic regression, Bayesian networks or a combination of both?. 19th international congress on modelling and simulation 2011; Perth, Australia. 2011; [Last date accessed: 09/23/2012]. pp. 1030–1036. Available from URL: http://www.mssanz.org.au/modsim2011/B4/gutierrez.pdf. [Google Scholar]