Abstract

Improving value within critical care remains a priority because it represents a significant portion of health-care spending, faces high rates of adverse events, and inconsistently delivers evidence-based practices. ICU directors are increasingly required to understand all aspects of the value provided by their units to inform local improvement efforts and relate effectively to external parties. A clear understanding of the overall process of measuring quality and value as well as the strengths, limitations, and potential application of individual metrics is critical to supporting this charge. In this review, we provide a conceptual framework for understanding value metrics, describe an approach to developing a value measurement program, and summarize common metrics to characterize ICU value. We first summarize how ICU value can be represented as a function of outcomes and costs. We expand this equation and relate it to both the classic structure-process-outcome framework for quality assessment and the Institute of Medicine’s six aims of health care. We then describe how ICU leaders can develop their own value measurement process by identifying target areas, selecting appropriate measures, acquiring the necessary data, analyzing the data, and disseminating the findings. Within this measurement process, we summarize common metrics that can be used to characterize ICU value. As health care, in general, and critical care, in particular, changes and data become more available, it is increasingly important for ICU leaders to understand how to effectively acquire, evaluate, and apply data to improve the value of care provided to patients.

US health care faces a value crisis. Despite spending more on health care per capita than any other country in the world, an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 Americans die annually from potentially preventable harm and frequently do not receive the recommended care that they should.1-3 Although progress has been made, improving value within critical care remains a priority because it represents as much as 11% of total health-care spending,4,5 faces high rates of adverse events,6 and inconsistently delivers evidence-based practices.7,8

ICU directors are increasingly required to understand all aspects of the value provided by their units. The drive to measure and improve value comes from the need to support internal efforts to improve quality and as a response to growing external scrutiny, including the public reporting of specific quality metrics and reimbursement tied to the quality of care. As such, ICU directors need a clear understanding of unit metrics to support efforts to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of care provided in their units.

The primary goal of this article is to familiarize ICU leaders with the fundamentals of measuring ICU quality and value. We briefly describe a conceptual framework for understanding the components of health-care value, provide an approach to develop a value measurement program, and summarize common metrics that can be used to characterize ICU value.

Conceptual Framework for Value

The Quality and Value Relationship

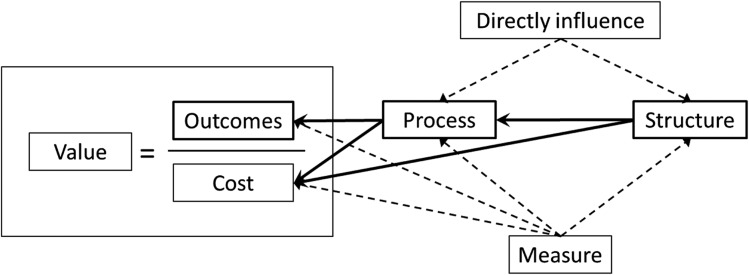

At a basic level, the value provided by an ICU can be conceptually defined as the simple equation of a given outcome divided by the cost associated with obtaining that outcome (Fig 1). Although this formula can be useful conceptually, this model does not capture all the nuances related to health-care outcomes and costs needed to operationally measure health-care value. Despite these limitations, the simplified formula can be useful to begin conceptualizing the relationships among the elements of value.

Figure 1 –

Relationship between value and quality components.

Outcomes can include (1) the quality of care (ie, the degree to which the ICU effectively addresses the patient’s medical condition), (2) the safety of care (ie, the risk of developing an adverse event from being in the ICU), and (3) the satisfaction of care (ie, patient and family experience of receiving care in the ICU). Cost includes both direct and indirect health-care costs associated with the ICU stay. Direct costs include pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and other material costs. Indirect costs include both financial and nonfinancial, such as the extensive hospital infrastructure needed to support ICU functions (eg, hospital building costs, hospital personnel salaries), pain and suffering associated with critical illness to the patient and family, provider emotional burnout, and the opportunity cost of critical illness (ie, patients, families, and providers not performing alternate activities because of the patient being in the ICU).

Determinants and Attributes of Quality Measures

Classically, assessing the quality of health-care delivery has been approached using Avedis Donabedian’s framework, which links three domains: structure, process, and outcome (ie, the S-P-O model).9,10 Structure refers to the conditions under which patients receive care and includes physical design attributes (eg, ICU room layout, location of sinks), materials (eg, medications, central line insertion carts, electronic medical record [EMR] systems), human resources (eg, number and education of staff), and organizational strategies to support standard practices (eg, decision support tools, communication tools, policies and protocols). Process refers to the care that patients actually receive and includes all actions designed to diagnose (eg, chest radiograph to evaluate for suspected pneumonia), treat (eg, antibiotic administration for sepsis), or prevent disease (eg, heparin for VTE prophylaxis). Outcomes are the end results of the care that patients receive, including mortality, morbidity, health-related quality of life, and health literacy. The S-P-O model can be integrated into the value equation to provide further insight into the modifiable factors that influence the determinants of value (Fig 1).

Each domain in the S-P-O model has specific characteristics that are useful when identifying potential ICU metrics. Structures can generally be directly modified by leaders using a variety of techniques, such as creating a central line insertion cart or modifying the ICU staffing model.11,12 However, these changes may vary in feasibility due to resource limitations attributed to either fiscal constraints or other organizational factors.13 Additionally, the impact of structural changes on health-care value is mediated by how this change influences the process of care delivery. Frequently, this means that structural metrics, while important, are insufficient to assess system change.

Process measures evaluate the actions of providers and most directly influence the outcome and cost determinants of health-care value. By reflecting discrete behaviors, process measures are particularly meaningful to clinicians because they can identify individually modifiable targets to improve patient care. Defining the eligible population for a given process measure is important to avoid measurement error. A process of care may be generally indicated in most patients with a disease but specifically contraindicated in selected individuals. For example, lung protective strategies are the standard of care for ARDS, frequently resulting in permissive hypercapnea.14 In this setting, a process of care is generally indicated to prevent iatrogenic ventilator-induced injury. However, it is appropriate to avoid permissive hypercapnea in a trauma patient with a traumatic brain injury and significant cerebral edema who also has ARDS following a pulmonary contusion. Although this strategy could technically be considered nonadherence to lung protective ventilation, it would still be in the best interest of the patient to avoid cerebral herniation. Due to limitations in fully defining the eligible population, 100% adherence to a specific process metric may not always be appropriate and should be accounted for when defining unit goals and interpreting these measures.

Outcomes measures are generally the most meaningful to patients, payers, and other stakeholders because they represent the end result of care. However, although outcome measures are important metrics for ICU directors to assess, they are not directly modifiable by unit leaders. Additionally, overall outcomes measures are difficult to directly link to a specific provider behavior, which hinders their utility in supporting ICU improvement activities if presented without associated structure and process metrics. Outcome metrics also have the significant limitation of being influenced by patient factors such as severity of illness and comorbid disease. To be maximally interpretable, outcome measures, therefore, frequently require accurate risk adjustment to facilitate comparisons between different ICUs or to evaluate changes over time.15 Although risk adjustment can help these comparisons, they are subject to inherent limitations, including the burden of additional data collection and variable performance across various populations.16

Building upon the Donabedian framework, the Institute of Medicine proposed in its 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, that high-quality health care should aim to be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.17 Safe care refers to the avoidance of injuries in the setting of therapy that is intended to help patients. Timely care seeks to minimize unnecessary and potentially harmful delays in health care. Effective care involves providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit (ie, avoiding underuse) and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (ie, avoiding overuse). Delivering patient-centered health care is respectful and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions. Efficient care seeks to optimize how care is provided to minimize system waste. Equitable care ensures that health care does not vary in quality based on patient sex, ethnicity, geography, and socioeconomic status. Although the Institute of Medicine report was not aimed at a particular medical specialty or component of the care continuum, these attributes are directly applicable to the desired outcomes in the ICU setting and, therefore, guide ICU value measurement.

Developing an ICU Value Measurement Process

When initially developing an ICU value measurement process, it is helpful for ICU leaders to engage a multidisciplinary team. Because value does not exist solely within a specific health-care discipline or specialty, discussions involving as many members of the ICU team—physicians, nurses, advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), pharmacists, respiratory therapists, dietitians, physical therapists, chaplains, social workers, and patient care assistants—can be crucial to a successful effort. For example, engaging team members from multiple disciplines can result in a more complete understanding of the factors influencing unit performance as well as facilitate subsequent interventions to improve value. Furthermore, early involvement of those who will be collecting and analyzing the data (eg, data analysts) in the process can be helpful because potential metrics are only valuable if their elements can be measured and analyzed. Finally, senior leadership in a health-care system often plays a key role in setting strategic priorities, focusing the ICU team on big-picture goals of a health-care entity, and providing necessary support. Within this broad context, multidisciplinary teams can be effective in developing and facilitating the measurement process and in designing and implementing interventions to improve unit performance. In developing a local approach to measurement, teams should optimally identify target areas (both external and internal), select meaningful and measurable metrics, acquire the necessary data, and analyze and disseminate the findings.

Identify Target Areas

External target areas and metrics for ICUs are typically predefined and mandated. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention collects surveillance data on health-care-associated infections, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections, through the National Healthcare Safety Network.18 In addition, active surveillance is ongoing through the National Healthcare Safety Network for ventilator-associated events (VAEs).19 A VAE is a newly defined entity comprising ventilator-associated conditions, infection-related ventilator-associated conditions, possible ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and probable VAP that is intended to take the place of the previous VAP surveillance definition, which had previously been publicly reported despite concerns over its validity and reproducibility.19 The Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services publically reports hospital data on a variety of metrics, including core measures, patient safety indicators, and inpatient quality indicators as part of its Hospital Compare website.20 Through the Choosing Wisely Campaign, groups such as the Critical Care Societies Collaborative and American Board of Internal Medicine are identifying measures that ICUs can take to more effectively use health-care resources.21,22 On the state level, several health departments have mandatory reporting requirements relevant to ICU quality and value.23,24

Payers are increasingly examining quality and value metrics with the transition from volume-based reimbursement models (ie, fee for service) to reimbursement based on quality of care (ie, value-based purchasing or pay for performance).25 The use of quality metrics to compare performance between individual providers and facilities is an integral part of these programs, and several ICU measures represent potential pay-for-performance targets. Through their public rating of hospitals based on metrics, health-care accrediting organizations, such as the Joint Commission, and large health-care purchasers, such as the Leapfrog Group, have also attempted to influence health-care quality in the ICU by proposing minimum staffing standards.13

When considering which value metrics to target for internal improvement efforts, ICU leaders and their teams can examine potential outcome and cost metrics for their units. Table 126-42 presents examples of global and organ system-specific value metrics with potential IOM domain classifications and operational descriptions. Teams may consider prioritizing which metric to evaluate by identifying those with the greatest opportunities for improvement and those that generate the most staff engagement. Rather than selecting a metric based on a single criterion (eg, potential impact, actionability), an alternate approach to prioritizing metrics can involve the unit team rating each candidate metric on specific attributes (described in more detail in the next section), including the perceived opportunity to improve (ie, importance), the ability to measure performance (ie, feasibility), and the ability to effect change (ie, actionability). By multiplying these component scores, teams could generate a priority score to help guide decision-making (eg, starting with the top-three metrics).43

TABLE 1 ] .

Examples of Value Metrics, Institute of Medicine Aim, and Description

| Metric | Aim | Description |

| Global | ||

| Unadjusted ICU mortality26, a | S, E, P, Q | Percentage of patients in the ICU who die in the ICU |

| Risk-adjusted ICU mortality27 | S, E, P, Q | Percentage of patients in the ICU who die in the ICU adjusted for severity of illness |

| Unadjusted ICU length of stay26, a | S, E, F | Mean ICU length of stay for all discharges (including deaths and transfers) |

| Delayed ICU admission26 | T, E, Q | Percentage of ICU admissions (excluding interhospital transfers) delayed ≥ 4 h between order and transfer |

| ICU readmission26 | S, E, P, F | Percentage of unplanned ICU readmissions within 48 h |

| Patient falls28 | S, P | Number of falls per 1,000 patient days |

| Pressure ulcers29 | S, E, P, F | Number of new-onset pressure ulcers per 1,000 patient days |

| Medication errors30 | S, T, E, F | Percentage of administered medication doses with errors |

| ICU costs4 | F | Average ICU costs per day |

| Patient/family satisfaction31 | P | Average level of reported satisfaction (Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit survey) |

| Neurologic | ||

| Pain32 | T, E, P | Percentage of patient days during which pain was evaluated four or more times per shift and at a nonsignificant level |

| Agitation32 | T, E, P | Percentage of patient days during which sedation was evaluated four or more times per shift and at either optimal or target sedation level |

| Delirium32 | S, E, P | Percentage of patient days during which delirium was evaluated once per shift and delirium not present |

| Weakness33 | S, E, P | Percentage of patients with clinically detected weakness with no plausible cause other than critical illness |

| Pulmonary | ||

| Mechanical ventilation duration26 | S, E, P, F | Mean number of days on mechanical ventilation for all patients receiving any invasive mechanical ventilation |

| ARDS34 | S, E, P, F | Number of new-onset ARDS per 1,000 ventilator days |

| Unplanned extubations35 | S, E, P, F | Number of unplanned extubations per 1,000 ventilator days |

| Infectious disease | ||

| CLABSI36, b | S, E, P, F | Number of CLABSIs per 1,000 catheter days |

| CAUTI37, b | S, E, P, F | Number of CAUTIs per 1,000 catheter days |

| Probable VAP38 | S, E, P, F | Number of probable VAPs per 1,000 ventilator days19 |

| MRSA infection26 | S, E, P, F | Number of MRSA infections per 1,000 patient days |

| VRE infection26 | S, E, P, F | Number of new-onset VRE infections per 1,000 patient days |

| Clostridium difficile infection39, a | S, E, P, F | Number of new-onset C difficile infections per 1,000 patient days |

| GI | ||

| GI bleeding40 | S, E, P, F | Percentage of patients in whom macroscopic bleeding develops, resulting in hemodynamic instability or the need for RBC transfusion |

| Hematologic | ||

| VTE41 | S, E, P, F | Percentage of patients with new-onset VTE |

| Transfusion reaction42, a | S, E, P, F | Percentage of transfused units with a reaction |

CAUTI = catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI = central line-associated bloodstream infection; E = effective; F = efficient; MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; P = patient centered; Q = equitable; S = safe; T = timely; VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia; VRE = vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

National Quality Forum endorsed.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network reporting.

Once a value target area has been identified, associated structures and processes should be evaluated to identify where to direct improvement efforts (Tables 2,44-60 361-65). For example, an ICU with a higher-than-average CLABSI rate may choose to focus on the structures and processes associated with improvements in this outcome rather than on multiple other possible alternative target areas in which it already performs well. It is also worth considering additional outcomes with which those structures and processes are associated because many interventions are linked to more than one outcome.66 For example, adherence to a ventilator liberation protocol may decrease the rate of VAEs, duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay.

TABLE 2 ] .

Examples of Process Metrics for Value

| Metric | Description |

| Global | |

| ICU nurse staffing12,60 | Average nurse:patient ratio |

| Daily rounds by an intensivist44 | Percentage of daily rounds led by an intensivist |

| Rounds including pharmacist45 | Percentage of daily rounds with clinical pharmacist present |

| Daily goals/safety checklist46 | Percentage of patient days with a completed daily goals checklist |

| Neurologic | |

| Effective pain assessment32, a | Percentage of patient days during which pain was evaluated four or more times per shift |

| Effective sedation assessment32, b | Percentage of patient days during which sedation was evaluated four or more times per shift |

| Effective delirium assessment32 | Percentage of patient days with delirium assessed using formal tool |

| Sleep promotion47 | Percentage of patient days with adherence to sleep promotion checklist |

| ICU mobilization48 | Percentage of patient days receiving mobility therapy |

| Pulmonary | |

| Head-of-bed elevation26 | Percentage of patient days where the head of bed is elevated ≥ 30° |

| Daily chlorhexidine oral care49 | Percentage of patient days where patients had oral care with chlorhexidine |

| Lung protective ventilation14,50 | Percentage of ventilator days on which patients with ARDS receive a tidal volume < 6.5 mL/kg predicted body weight and plateau pressure ≤ 30 cm H2O |

| Ventilator liberation protocol26,51 | Percentage of ventilator days with protocol screening and completion |

| Cardiac | |

| Severe sepsis bundle52, a | Percentage of patients with severe sepsis for whom lactate level was measured, blood culture obtained prior to antibiotic administration, and broad-spectrum antibiotics administered within 3 h |

| Septic shock bundle52, a | Percentage of patients with septic shock for whom the severe sepsis bundle was met within 3 h and vasopressors were administered, central venous pressure and central venous oxygen saturation were measured, and lactate level was rechecked (if initially ≥ 4 mmol/L) within 6 h |

| Infectious disease | |

| Hand hygiene compliance53 | Percentage of opportunities where health-care workers adhered to hand hygiene guidelines |

| Blood cultures for CAP54,55, a | Percentage of ICU patients with CAP with one or more sets of blood cultures performed within 24 h prior to or 24 h after hospital admission |

| CVC insertion protocol36, a | Percentage of CVC insertions in which the CVC was inserted with all elements of maximal sterile barrier technique (cap AND mask AND sterile gown AND sterile gloves AND large sterile sheet AND hand hygiene AND 2% chlorhexidine for cutaneous antisepsis) |

| GI | |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis26 | Percentage of ventilator days with stress ulcer prophylaxis administration |

| Enteral nutrition56 | Percentage of patients receiving enteral nutrition within 24 h of ICU admission |

| Hematologic | |

| DVT prophylaxis57, a | Percentage of patient days with DVT prophylaxis administration |

| Appropriate use of blood transfusions58, b | Percentage of nonbleeding, hemodynamically stable patients receiving any RBC transfusion with a pretransfusion hemoglobin level ≤ 7 g/dL |

| Palliative | |

| Surrogate decision-maker59, b | Percentage of patients for whom a surrogate decision-maker or the absence of a surrogate is documented within 24 h of ICU admission |

| Goals of care59 | Percentage of patients for whom goals of care are documented within 72 h of ICU admission |

CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; CVC = central venous catheter.

National Quality Forum endorsed.

Critical Care Societies Collaborative22 and American Board of Internal Medicine “Choosing Wisely” endorsed.

TABLE 3 ] .

Structural Intervention Types and Examples

| Structural Intervention Type | Example |

| Physical design attributes | |

| ICU layout | Ambient noise in ICU61 |

| Materials | |

| Equipment | Central line insertion cart11 |

| Medications | Antibiotics on unit for severe sepsis62 |

| Human resources | |

| Staff number | Interdisciplinary rounding with clinical pharmacists45 |

| Staff education | Simulation-based learning for medication administration30 |

| Organizational strategies | |

| Provider organization | Closed-ICU physician staffing model12,44,63 |

| Policies | Transfusion policy58 |

| Protocols | Paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol64 |

| Decision support | Daily reminders to remove urinary catheters37 |

| Communication tools | Daily goals46 |

| Monitoring and feedback system | Weekly feedback regarding sepsis care65 |

Select an Appropriate Metric

Metrics should be important, feasible, valid, and actionable (Table 4).67 Important structure and process metrics are closely associated with important outcomes (eg, morbidity, mortality, cost). Selected structure or process measures should be strongly linked to important outcomes. The type of ICU should also be considered because the importance of metrics may vary depending on the patient population. For example, surgical site infection rates are important to surgical ICUs but less so for medical ICUs.

TABLE 4 ] .

Desirable Value Metric Attributes

| Attribute | Meaning |

| Important | Does the metric represent something important to the clinicians and patients in the ICU? Is there room for improvement? |

| Feasible | What resources are required to collect and analyze the data for this metric? |

| Valid | How well does the metric reflect what it is intending to convey (internal validity)? How well does the measure produce consistent results when collected by different people (ie, interrater reliability)? How well can the metric be replicated between ICUs for comparison (external validity)? |

| Actionable | Can an intervention be instituted to influence the metric? Does the measure respond to interventions designed to change it? |

Feasible metrics are based on data that are accessible and can be evaluated using available resources. Factors to consider when judging feasibility include the cost of data collection, impact on clinician workload, accessibility of potential data sources, and availability of individuals with the requisite data analysis skills.

Valid metrics accurately reflect the outcome, process, or structures that they intend to measure. The target audience must believe that the metrics measure what they are designed to measure (ie, face validity), yield consistent results when collected by different individuals (ie, interrater reliability), and are replicable between different ICUs (eg, external validity). For example, the validity of using the prior VAP surveillance definition as an outcome metric was regularly questioned, including the fact that the surveillance definition for VAP detected a significant number of patients who did not have pneumonia, it was unclear how many patients with pneumonia were missed by the diagnosis, and evaluators frequently classified potential VAP cases differently.68,69 For these reasons, the alternative VAE metrics have been developed, with public reporting not currently mandated while validity and benchmarks are being evaluated.19 Similarly, process metrics should effectively depict the behaviors that leaders are seeking to measure. For instance, rates of documented adherence to the central line insertion bundle elements should reflect the realities of clinical care, which frequently require intermittent quality checking and audits by team members.

Actionable metrics can be influenced directly or indirectly by deliberate interventions. For a measure to be actionable there must be room for improvement and an identifiable process or structure that can be changed to lead to improvement, and the metric needs to change in response to the improvement. For example, ICUs with high CLABSI or catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates can implement evidence-based strategies to improve and monitor their rates for improvement more readily than those with lower rates.36,70 These ICUs should also focus on measuring and improving the related structures and processes that can be influenced and have the greatest room for improvement.

Acquire the Necessary Data

After defining the measure to be targeted, data sources need to be identified to measure the metric being examined. Potential data sources include administrative data, clinical data, surveys, and ancillary data (Table 571). Administrative data are usually readily available, with no additional burden for collection. Clinical data can be obtained prospectively or retrospectively from medical records by manual review or direct extraction from EMR databases. Prospectively collected clinical data often require the commitment of human and financial resources, which can limit feasibility, particularly if collection involves large volumes of data or long assessment periods. Survey data include patient satisfaction surveys, such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey and the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit survey, as well as patient safety culture questionnaires, such as the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety.72-74 Ancillary data can be found in additional monitoring systems, such as infection surveillance systems and adverse event reporting systems.

TABLE 5 ] .

Potential Data Sources for Value Metrics

| Data Source | Benefits | Limitations | Typical Use (Example) |

| Administrative | Commonly available across institutions for large groups of patients No new data collection required |

Delay in coding (not real time) Limited granularity Potential for coding errors |

Structure (staffing ratio12) Process (RBC transfusion58) Outcome (length of stay) Cost (cost/d4) |

| Manual chart abstraction | Good detail on focused areas Can translate free text from chart into more-structured data |

Resource intensive per chart reviewed Limited scalability Depends on clinician documentation |

Process (antibiotic administration for sepsis52) Outcome (length of stay) |

| EMR extraction | Larger population More discrete clinical data Potential to automate measurement, reducing ongoing resource utilization (more efficient in the long run) Potential real-time assessment |

Depends on clinician documentation Initial development cost Advance system planning required (eg, variables, data repositories) Balance between discrete data and narrative |

Process (antibiotic administration for sepsis52) Outcome (length of stay) |

| Survey | Provides data commonly not present in the medical record May be scaled depending on scope of project |

Respondent burden Limited ability to integrate into other data reporting |

Structure (staffing ratio12) Outcome (patient satisfaction71) |

| Ancillary system (eg, infection surveillance and adverse event reporting systems) | Provide information commonly not present in medical records | Challenging to integrate with other systems for data gathering and reporting purposes Initial cost to develop system |

Outcome (CLABSI36) Outcome (unplanned extubation35) |

EMR = electronic medical record. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Much of the necessary data for an ICU are available in EMRs. Although EMRs are a valuable source for data on the quality of care, data extraction can require specialized training. Optimally, EMR vendors would ensure that the data needed to evaluate the quality and value of care are easy to obtain through both customizable reports and easier access to raw data for more detailed analysis; however, the ability to obtain these data from EMRs is currently variable. As such, individual hospitals and health systems often need to invest substantially in the human resources required to effectively use these information systems to reduce the burden of data collection.75

Data collection processes should also be pilot tested to ensure their feasibility and reliability. Leaders need to balance the feasibility of data collection and efficiency of measurement with the need for detailed results. If the data are to support a small, preliminary local evaluation, then efficiency is likely to be weighted more. If the scope of the work increases or the project will be ongoing, then the process may need to transition to more precise and automated collection and reporting methods.

Analyze and Disseminate the Findings

Once the data have been collected, they need to be analyzed and disseminated in an easily interpretable manner for target audiences. Frequently, successful completion of this task requires a data analyst or team with both statistical and clinical expertise along with access to necessary data analysis software. Given the smaller sample size of an ICU compared with the hospital or health system, statistical significance may be harder to detect and less meaningful than presenting data exceeding clinically significant bounds.76

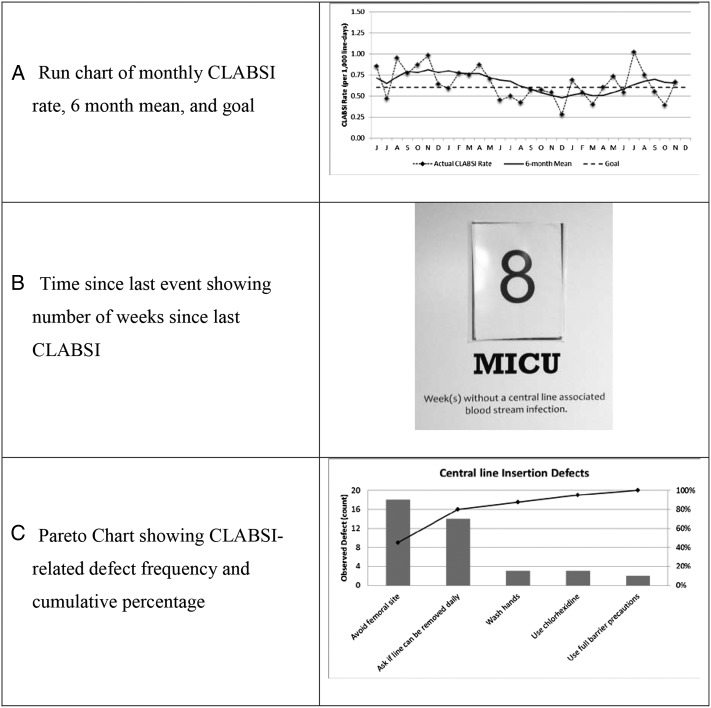

Selecting an approach to display quality data can be influenced by the type of information being communicated and the goal of the communication, understanding that multiple, nonmutually exclusive goals may exist simultaneously. For example, if the goal is to show a change over time in relatively common occurrences (eg, CLABSI rates across multiple ICUs), then run charts can enable immediate appreciation of trends (Fig 2A).77 If the goal is to foster competition, then unit data can be displayed relative to internal goals or external benchmarks using overlapping run charts or side-by-side bar graphs. For metrics with a low rate in a small number of opportunities (eg, CLABSIs in small ICUs), time since last event can be helpful (Fig 2B). Pareto charts, which show a combination of prioritized individual components (bars) along with a cumulative measure (line), can help to prioritize process and structure targets that contribute to specific outcomes (Fig 2C).77

Figure 2 –

A-C, Example run chart (A), time since last event (B), and Pareto chart (C) related to CLABSIs. CLABSI = central line-associated bloodstream infection; MICU = medical ICU.

Evidence suggests that displaying ICU data for staff to review improves adherence with guidelines.78 Scorecards are one method for displaying unit data, which can help to prioritize local needs, support audit and feedback, and track changes over time.79,80 Scorecards can present data at various levels, such as aggregated to the unit level or granular down to the individual provider level. When considering the level of granularity of data presentation, unit directors should consider their ability to effectively attribute the metrics to a specific provider and balance the level of provider identification (eg, unit level, deidentified provider indicators, provider names) with the organizational culture of the ICU (eg, transparency, fair and just culture).

Conclusions

Quality and value metrics are gaining increasing prominence in a rapidly shifting health-care landscape. ICU directors are responsible for facilitating the delivery of high-quality and high-value care for patients within their ICUs. Improving the ability of ICU directors to identify, obtain, and evaluate relevant metrics is critical to ensuring that these units consistently deliver high-quality, high-value health care.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor played no role in the development of the manuscript beyond financial support.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CLABSI

central line-associated bloodstream infection

- EMR

electronic medical record

- S-P-O

structure, process, outcome

- VAE

ventilator-associated event

- VAP

ventilator-associated pneumonia

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health [GM095442].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health policies and data: OECD health statistics 2014. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development website. http://www.oecd.org/health/healthdata. Published 2014. Accessed June 1, 2014.

- 4.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coopersmith CM, Wunsch H, Fink MP, et al. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1072-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothschild JM, Landrigan CP, Cronin JW, et al. The Critical Care Safety Study: the incidence and nature of adverse events and serious medical errors in intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1694-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewson-Conroy KM, Burrell AR, Elliott D, et al. Compliance with processes of care in intensive care units in Australia and New Zealand—a point prevalence study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(5):926-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. AHRQ publication 14-0005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donabedian A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003:1-200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA, et al. Eliminating catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(10):2014-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treggiari MM, Martin DP, Yanez ND, Caldwell E, Hudson LD, Rubenfeld GD. Effect of intensive care unit organizational model and structure on outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(7):685-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parikh A, Huang SA, Murthy P, et al. Quality improvement and cost savings after implementation of the Leapfrog intensive care unit physician staffing standard at a community teaching hospital. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(10):2754-2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garland A. Improving the ICU: part 1. Chest. 2005;127(6):2151-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angus DC, Clermont G, Kramer DJ, Linde-Zwirble WT, Pinsky MR. Short-term and long-term outcome prediction with the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II system after orthotopic liver transplantation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(1):150-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobbin CJ, Bartlett D, Melehan K, Grunstein RR, Bye PT. The effect of infective exacerbations on sleep and neurobehavioral function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(1):99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magill SS, Klompas M, Balk R, et al. Developing a new, national approach to surveillance for ventilator-associated events. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22(6):469-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Data.Medicare.gov website. https://data.medicare.gov. Accessed May 25, 2014.

- 21.Good Stewardship Working Group. The “top 5” lists in primary care: meeting the responsibility of professionalism. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1385-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halpern S, Becker D, Curtis J, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/American Association of Critical Care Nurses/American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine policy statement: the Choosing Wisely top 5 list in critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(7):818-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, Jr, Lipsett PA, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr Variation in postoperative complication rates after high-risk surgery in the United States. Surgery. 2003;134(4):534-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy DJ, Needham DM, Goeschel C, Fan E, Cosgrove SE, Pronovost PJ. Monitoring and reducing central line-associated bloodstream infections: a national survey of state hospital associations. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(4):255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien JM, Jr, Kumar A, Metersky ML. Does value-based purchasing enhance quality of care and patient outcomes in the ICU? Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(1):91-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Ngo K, et al. Developing and pilot testing quality indicators in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2003;18(3):145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb SE, Jørstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C; Prevention of Falls Network Europe and Outcomes Consensus Group. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1618-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaratkiewicz S, Whitney JD, Lowe JR, Taylor S, O’Donnell F, Minton-Foltz P. Development and implementation of a hospital-acquired pressure ulcer incidence tracking system and algorithm. J Healthc Qual. 2010;32(6):44-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford DG, Seybert AL, Smithburger PL, Kobulinsky LR, Samosky JT, Kane-Gill SL. Impact of simulation-based learning on medication error rates in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(9):1526-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasser T, Pasquale MA, Matchett SC, Bryan Y, Pasquale M. Establishing reliability and validity of the critical care family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):192-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. ; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kress JP, Hall JB. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1626-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. ; ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birkett KM, Southerland KA, Leslie GD. Reporting unplanned extubation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2005;21(2):65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725-2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang W-C, Wann S-R, Lin S-L, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care units can be reduced by prompting physicians to remove unnecessary catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(11):974-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coffin SE, Klompas M, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(suppl 1):S31-S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lofgren ET, Cole SR, Weber DJ, Anderson DJ, Moehring RW. Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infections: estimating all-cause mortality and length of stay. Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):570-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Walter SD, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. The attributable mortality and length of intensive care unit stay of clinically important gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2001;5(6):368-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards M, Felder S, Ley E, et al. Venous thromboembolism in coagulopathic surgical intensive care unit patients: is there a benefit from chemical prophylaxis? J Trauma. 2011;70(6):1398-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiersum-Osselton JC, van Tilborgh-de Jong AJ, Zijlker-Jansen PY, et al. Variation between hospitals in rates of reported transfusion reactions: is a high reporting rate an indicator of safer transfusion? Vox Sang. 2013;104(2):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gurses AP, Murphy DJ, Martinez EA, Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ. A practical tool to identify and eliminate barriers to compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(10):526-532., 485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Heitmiller RF, Lipsett PA. Intensive care unit physician staffing is associated with decreased length of stay, hospital cost, and complications after esophageal resection. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(4):753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horn E, Jacobi J. The critical care clinical pharmacist: evolution of an essential team member. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl):S46-S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, Lipsett PA, Simmonds T, Haraden C. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18(2):71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(8):2238-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rello J, Afonso E, Lisboa T, et al. ; FADO Project Investigators. A care bundle approach for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(4):363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McConville JF, Kress JP. Weaning patients from the ventilator. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2233-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. ; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marra AR, Moura DF, Jr, Paes AT, dos Santos OF, Edmond MB. Measuring rates of hand hygiene adherence in the intensive care setting: a comparative study of direct observation, product usage, and electronic counting devices. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):796-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, et al. ; American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1730-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dedier J, Singer DE, Chang Y, Moore M, Atlas SJ. Processes of care, illness severity, and outcomes in the management of community-acquired pneumonia at academic hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(17):2099-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doig GS, Simpson F, Finfer S, et al. ; Nutrition Guidelines Investigators of the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Effect of evidence-based feeding guidelines on mortality of critically ill adults: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2731-2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bilimoria KY, Chung J, Ju MH, et al. Evaluation of surveillance bias and the validity of the venous thromboembolism quality measure. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1482-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Napolitano LM, Kurek S, Luchette FA, et al. ; American College of Critical Care Medicine of the Society of Critical Care Medicine; Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Workgroup. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(12):3124-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl):S404-S411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Checkley W, Martin GS, Brown SM, et al. Structure, process, and annual ICU mortality across 69 centers: United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group Critical Illness Outcomes Study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):344-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joseph A, Ulrich R. Sound Control for Improved Outcomes in Healthcare Settings. Concord, CA: Center for Health Design; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hitti EA, Lewin JJ, III, Lopez J, et al. Improving door-to-antibiotic time in severely septic emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(4):462-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iyegha UP, Asghar JI, Habermann EB, Broccard A, Weinert C, Beilman G. Intensivists improve outcomes and compliance with process measures in critically ill patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):363-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schramm GE, Kashyap R, Mullon JJ, Gajic O, Afessa B. Septic shock: a multidisciplinary response team and weekly feedback to clinicians improve the process of care and mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):252-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berenholtz SM, Dorman T, Ngo K, Pronovost PJ. Qualitative review of intensive care unit quality indicators. J Crit Care. 2002;17(1):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Curtis JR, Cook DJ, Wall RJ, et al. Intensive care unit quality improvement: a “how-to” guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tejerina E, Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P, et al. Accuracy of clinical definitions of ventilator-associated pneumonia: comparison with autopsy findings. J Crit Care. 2010;25(1):62-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klompas M. Interobserver variability in ventilator-associated pneumonia surveillance. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):237-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stéphan F, Sax H, Wachsmuth M, Hoffmeyer P, Clergue F, Pittet D. Reduction of urinary tract infection and antibiotic use after surgery: a controlled, prospective, before-after intervention study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(11):1544-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wall RJ, Curtis JR, Cooke CR, Engelberg RA. Family satisfaction in the ICU: differences between families of survivors and nonsurvivors. Chest. 2007;132(5):1425-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland DK, Curtis JR. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldstein E, Farquhar M, Crofton C, Darby C, Garfinkel S. Measuring hospital care from the patients’ perspective: an overview of the CAHPS Hospital Survey development process. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 pt 2):1977-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sorra JS, Dyer N. Multilevel psychometric properties of the AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pronovost PJ, Nolan T, Zeger S, Miller M, Rubin H. How can clinicians measure safety and quality in acute care? Lancet. 2004;363(9414):1061-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. The advantages and disadvantages of process-based measures of health care quality. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(6):469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gershengorn HB, Kocher R, Factor P. Management strategies to effect change in intensive care units: lessons from the world of business. Part II. Quality-improvement strategies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):444-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kastrup M, Nolting MJ, Ahlborn R, et al. An electronic tool for visual feedback to monitor the adherence to quality indicators in intensive care medicine. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(6):2187-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ. Monitoring patient safety. Crit Care Clin. 2007;23(3):659-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]