Abstract

In the past two decades, microfluidics has become of great value in precisely aligning cells or microparticles within fluids. Microfluidic techniques use either external forces or sheath flow to focus particulate samples, and face the challenges of complex instrumentation design and limited throughput. The burgeoning field of inertial microfluidics brings single-position focusing functionality at throughput orders of magnitude higher than previously available. However, most inertial microfluidic focusers rely on cross-sectional flow-induced drag force to achieve single-position focusing, which inevitably complicates the device design and operation. In this work, we present an inertial microfluidic focuser that uses inertial lift force as the only driving force to focus microparticles into a single position. We demonstrate single-position focusing of different sized microbeads and cells with 95~100% efficiency, without the need for secondary flow, sheath flow or external forces. We further integrate this device with a laser counting system to form a sheathless flow cytometer, and demonstrated counting of microbeads with 2200 beads/s throughput and 7% coefficient of variation. Cells can be completely recovered and remain viable after passing our integrated cytometry system. Our approach offers a number of benefits, including simplicity in fundamental principle and geometry, convenience in design, modification and integration, flexibility in focusing of different samples, high compatibility with real-world cellular samples as well as high-precision and high-throughput single-position focusing.

Introduction

Microfluidics has received considerable attention in recent years for ordering and focusing cells and microparticles into a single stream inside microchannels for a variety of biomedical and clinical applications1–4. Some of the promising advantages of such systems include reduced sample volume, faster sample processing, high efficiency, high throughput and low cost1. Active microfluidic systems that rely on acoustic5–7, dielectrophoretic8, 9, or optical10, 11 principles to focus microparticles into a single stream have been reported. They often offer high precision and efficiency, but require sophisticated external controls and complex device fabrication1. Conversely, passive techniques rely on the inherent hydrodynamics to order microparticles. For instance, hydrodynamic focusing1, 12–14 is the most widely-used passive technique for particle focusing in which one or multiple sheath flows are used to pinch particle sample flow into a band (2D focusing) or a single stream (3D focusing). Although conceptually simple, this approach requires additional fluidic instrumentation and a delicate balance of sheath and sample flows to generate tight focusing, which complicates the setup and operation. Other passive techniques such as hydrophoretic drifting15 use channel geometry-induced pressure field to focus microparticles without the need of sheath flow. This dramatically simplifies the system, but leads to a very limited throughput (<1µL/min)15.

Inertial microfluidics has been receiving considerable attention in recent years for the ability to passively focus16–19 and sort20–31 microparticles at throughputs that are orders of magnitude higher than other techniques32–36. Inertial microfluidics uses the inertial effect of fluids around microparticles to drive them across flow streamlines and order them into equilibrium positions in microscale channels33, 34. Recent studies demonstrated precise 3D single-position focusing with high throughput and without the use of sheath flow and or external forces. Oakley et al.37 used asymmetric serpentine channel to introduce cross-sectional secondary flow entraining particles into a single position in the downstream channel. Bhagat et al.38 used spiral channel to introduce Dean flows for 3D focusing of microbeads and cells. Recently, Chung et al.39, 40 reported the use of microstructure array such as micropillars or microcavities to generate cross-sectional secondary flow for 3D focusing.

While precise focusing of cells and particles with throughput as high as ~mL/min38 and 2,000~36,000 particles/s (depending on the particle concentration)38, 39 has been achieved, these inertial microfluidic focusers rely on a combination of inertial lift and drag forces induced by secondary flows to confine the focusing position37–40. This inevitably increases the complexity of device design and operation. For example, to focus microparticles in a spiral channel, one needs to carefully design and match multiple variables including the diameter of particles, the radius of curvature, channel length, cross-sectional dimension, and input flow41. Further, different sized microparticles exhibit distinct focusing behaviors17, which further complicates the device operation. The devices with microstructure array share similar challenges in which the use of inertial lift forces and additional secondary flow-induced drag restricts the design and operation parameters.

In this work, we demonstrate a microfluidic chip that uses inertial lift as the only key driving force to focus cells and microparticles into a single-position. Our device consists of a low-aspect-ratio channel bifurcated into high-aspect-ratio channels with different hydrodynamic resistances. Based on our two-stage model of inertial focusing34, we combined inertial migration with asymmetric flow separation to achieve precise focusing of microparticles. Through theoretical and experimental investigations, we illustrate the focusing principle with ~100% efficiency at the optimal Reynolds number Re = 40. Further, we integrated the device with a laser counting system38 to form a sheathless flow cytometr and showed counting of 15µm diameter microbeads with efficiency of ~100% and throughput of ~2,200 beads/s. We also demonstrated counting of fibroblast cells with a throughput of ~850 cells/s, with ~100% efficiency, recovery rate, and viability, indicating compatibility of this device with live cell samples. We envision this inertial microfluidic focuser can serve as a powerful microfluidic unit for sheathless, high throughput focusing of microparticle samples contributing to the development of cytometry as well as other biomedical, clinical, and diagnostic sample preparations.

Results

Sheathless 3D focusing in straight microchannel

Sheathless 3D focusing of microparticles in a straight microchannel is achieved by taking advantage of inertial migration and hydrodynamic flow separation. Our device consists of a low-aspect-ratio (LAR) microchannel (channel width w > channel height h) as the upstream segment, which bifurcates into high-aspect-ratio (HAR) channels (h>w) downstream (Fig. 1a). The upstream LAR microchannel uses inertial lift forces to order microparticles into equilibrium positions near the centers of top and bottom walls (Fig. 1b). Downstream, the HAR channels with hydrodynamic resistance R2>R1 further entrain microparticles into a single-position. The difference in hydrodynamic resistance between HAR channels leads to asymmetric flow separation at the bifurcation (Fig. 1c). As a result, the center streamline along which microparticles focus in the upstream channel (red dash line) contorts into channel 1 near the inner sidewall (Fig. 1c). The focused microparticles follow the central streamline and selectively enter channel 1 near the inner sidewall. Further downstream, particles migrate along the inner sidewall towards the center subject to the rotation-induced lift force FΩ. Ultimately, particles equilibrate at the center of the inner sidewall of channel 1, achieving sheathless 3D focusing at the same cross-sectional position.

Figure 1.

Sheathless 3D focusing in a straight microchannel. (a) Schematic of device principle. Lu represents the length of upstream channel. Ld represents the length of downstream channel 1. Inertial migration (b) and asymmetric flow separation (c) are combined to gradually manipulate particle cross-sectional position to achieve single-position focusing. The blue solid line in (c) indicates the separation boundary of the flow. The red dash line indicates the central streamline in upstream LAR channel. R1 and R2 represent the hydrodynamic resistance of downstream HAR channel 1 and channel 2. (d) Bright field and fluorescence images at three downstream positions showing 15µm diameter particles gradually focus into a single focal position at Re=40. Blue and red dash circles indicate microbeads focused at top and bottom channel walls. Green dash circles indicate 3D focused microbeads. (e) Single-position focusing in the present device and two-position focusing in a normal straight HAR channel as control.

To demonstrate device concept, we focused FITC-labeled 15µm diameter polymer microbeads in a PDMS channel at Re = 40. The channel height was fixed at h = 50µm, while the channel width was wu = 75µm upstream and wd = 30µm downstream. The downstream channel length was adjusted to a resistance ratio of R2/R1 = 3. As illustrated in Fig. 1d, microbeads were uniformly dispersed in the fluid shown as a fluorescent band spanning the entire width at the channel entrance (Lu=0mm). As microbeads traverse downstream, they gradually migrate to the center of the channel, as indicated by a bright fluorescent streak at Lu = 25mm. The bright field image at the same downstream position suggests that particles are positioned at two different focal planes near the top and bottom walls, appearing as dark and bright spheres due to differences in vertical planes (indicated with blue and red dash circles). At bifurcation, particle streaks appear in the downstream channel 1, indicating that particles selectively enter it due to asymmetrical separation of flow. Further downstream, bright field images at Ld = 10mm show that all microparticles are focused at the center of the inner sidewall, appearing as consistent bright spheres indicating successful 3D focusing in the same vertical plane (Fig. 1e)19, 37, 39, 40. In a control HAR channel, particles focus into two positions at the center of each sidewall.

Designing device dimensions

The lengths of the upstream LAR and the downstream HAR channel segments can be designed using the two-stage inertial migration model that describes inertial focusing in a microchannel with rectangular cross-section34. The minimum downstream length L necessary for focusing microparticles with diameter a in a channel with cross-sectional dimensions w×h is given by

| (1) |

where μ is fluid viscosity, ρ is fluid density, Uf is the average flow velocity, and Dh = 2wh/ (w+h) is the hydraulic diameter, is the negative lift coefficient related to the first stage of migration, and is the positive lift coefficient related to the second stage migration. Values for and can be obtained from our earlier work34. Fig. 2 illustrates calculated downstream lengths for focusing of particles a = 7–20 µm in diameter in microchannels with cross-sectional dimensions ranging from 50µm×30µm to 125µm×50µm. These calculations show that larger particles require a shorter microchannel to focus due to the inertial lift forces that scale with particle diameter as FL~a4,21, 42. These results also suggest that using channels with a smaller cross-section shortens the focusing channel, which is due to the increased inertial lift forces (FL~Dh−2) in smaller channel cross-section34.

Figure 2.

Designing length of the focusing channel. (a) Theoretical calculation of the upstream low-aspect-ratio channel length Lu for focusing particles with diameter a = 7µm to a = 20µm into two focal positions near centers of top and bottom walls. (b) Theoretical calculation of the downstream length of HAR channel 1 Ld for further single position focusing. (c) Summary of channel cross-sectional dimensions of upstream and downstream segments for designs D1 to D4.

While designing the proper length of microchannel is critical for focusing of microparticles, the resistance ratio R2/R1 of the downstream HAR channels dictates separation of the flow at bifurcation which is critical to entraining microparticles into the correct flow region downstream (Fig. 3). We developed a CFD-ACE+ model of the separation at the bifurcation of the upstream and the downstream sections. We used constant flow at Re = 40 and varied the resistance ratio R2/R1 from 1 to ∞. The resistance ratio R2/R1 was achieved by varying length of downstream channels 1 and 2. The device with R2/R1=∞ was fabricated by selectively punching only the outlet of channel 1. As shown in Fig. 3a, at channel resistance ratio R2/R1= 1, flow is symmetrically separated. The central streamline (red dash line) and the separation boundary (blue solid line) overlap. Thus, the center-focused particles can enter either channel leading to two positions in channel 1 and 2. At R2/R1= ∞, the flow only enters channel 1 (Fig. 3c). The central streamline stretches downstream to the center of channel 1 where the focused microparticles will be located. As a consequence, microparticles migrate towards either side wall leading to two possible positions in channel 1. At 1<R2/R1<∞, the flow is asymmetrically bifurcated (Fig. 3b). The central streamline of the upstream channel extends to the half of the HAR channel 1 near the inner channel wall. Following the central streamline, particles relocate near the inner wall of channel 1 and focus in a single-position further downstream. The bright field images in Fig. 3a–c demonstrate particle motion at the bifurcation at R2/R1=1, 3 and ∞ validating the numerical simulation. The numerical results indicate a flexibility of resistance ratio (1< R2/R1<∞) for fully-focused microparticles in the upstream LAR channel to fulfill single-position focusing downstream.

Figure 3.

Designing the resistance ratio R2/R1. (a) CFD-ACE+ numerical simulations, downstream focusing pattern and experimental bright field images demonstrating flow separation at the bifurcation and corresponding microparticle focusing behaviour at (a) R2/R1 = 1, (b) R2/R1=3, and (c) R2/R1=∞. The red dash line represents the central streamline. The blue solid line represents flow separation boundary. The scale bar is 75µm. (d) CFD-ACE+ simulation at R2/R1=10 illustrates the effective focusing region indicated as the grey area. The yellow dash line is the mirror image of the yellow solid line against the red central streamline. (e) Quantitative study of the width of the effective focusing region at increasing R2/R1. The grey area represents width of the effective focusing region at different R2/R1. The red dotted arrow indicates the widest effective focusing region locating at R2/R1=3. The blue solid dots represent positions of the boundary streamline. The blue hollow dots represent the mirror positions against central streamline at y=0. The yellow solid dots represent the positions of secondary central streamline. The yellow hollow dots represent the mirror positions against y=0.

The resistance ratio R2/R1 can be further refined to maximize tolerance to inertial focusing in the upstream microchannel. Providing the tolerance to inertial focusing is essential for processing samples with high concentration (e.g., >106/mL) in which microparticles may not be able to focus into narrow streaks along the central streamline due to interparticle interactions. To elucidate the resistance ratio R2/R1 for maximum tolerance, we examined flow separation at channel bifurcation at R2/R1=10. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, the blue solid line indicates the separation boundary of the flow located at y=−w/2+|d3|. The distance between the boundary and the central streamline is |d1|. The yellow solid line at y=−w/2+|d3|/2 is the secondary central streamline and represents the streamline that stretches to the center of the downstream HAR channel 1. The distance between the secondary central streamline and the central streamline is |d2|.

Microparticles focused between the boundary and the secondary central streamlines can be entrained downstream for single position focusing, while microparticles outside the region will either enter channel 2 or be focused near the outer sidewall of channel 1(indicated as hollow circles). Considering the symmetry of inertial focusing around the central streamline at y=0, the effective focusing region is defined as the area around the central streamline with a width of 2|dn| (n can be 1 or 2 depending on which streamline is closer to the central streamline). For example, at R2/R1=10, |d2|<|d1| and the effective region has a width of 2|d2| around the central streamline, shown as the grey region in Fig. 3d. As resistance increases from 1 to ∞, the boundary streamline shifts up with the normalized distance |d1/w| increasing from 0 to 0.5 (Fig. 3e). The secondary streamline shifts with the boundary with the normalized distance |d2/w| decreasing from 0.25 to 0. As a result, the width of the effective region 2|dn/w| first increases with the resistance ratio at R2/R1=1~3 from 0 to 0.32. Then it gradually decreases as R2/R1>3. The widest effective region 2|dn/w| equals 0.32 at R2/R1=3. It indicates the optimal resistance ratio at R2/R1=3 that provides the maximum tolerance to inertial focusing (Fig. 3e).

Optimizing Re for 3D focusing with high efficiency

Channel Re can be optimized to achieve 3D focusing with high efficiency. We used polymer microbeads with a diameter of 15µm to investigate inertial focusing at Re = 2.6~78. At Re = 2.6, microbeads focused into a band at the bifurcation in the upstream LAR section because of limited inertial effect at low Re (Fig. 4a). As a result, microparticles equilibrated at multiple positions downstream. At Re = 26, microparticles experience stronger inertial lift forces (FL~Uf2)19 and migrate to the equilibrium positions at the centers of top and bottom walls in the upstream LAR segment. Following the central streamline, microparticles entrained into HAR channel 1 and focused into a single position downstream. Increasing flow to Re = 78, two additional equilibrium positions emerge near the side walls in the LAR channel due to weaker effects of the wall force33. Microparticles at the two additional positions are outside the effective focusing region leading to multiple positions downstream. The linescans of fluorescent intensity peaks at Lu=25mm show that the intensity peaks narrow as Re increases from 2.6 to 78 (Fig. 4b). Notably, at Re=78, two additional intensity peaks appear near the sidewalls, validating the experimental observations in bright field images. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the intensity peaks decreases from ~27µm, until it saturates at ~15µm for Re > 13, suggesting sufficient inertial migration to equilibrium positions.

Figure 4.

Optimizing Re for 3D focusing with high efficiency. (a) Experimental observation at Lu=25mm and Ld=10mm at Re=2.6, 26 and 78. The blue arrows indicate additional equilibrium positions at Re=78. The green dotted line indicates expected focusing position. The scale bar is 75µm. (b) Linescans of fluorescent intensity at Lu=25mm at Re=2.6 ~ 78. The blue arrows indicates the additional fluorescent intensity peaks at Re=78. (c) Quantitative measurement of focusing efficiency at increasing Re (n=3).

We defined efficiency of 3D single-position focusing as the ratio of the number of microparticles focused at the center of the inner sidewall of channel 1 (green dotted line) and the total number of microparticles (see Data Analysis section of Methods for details). As shown in Fig. 4c, the results indicate a focusing efficiency as high as ~99% at Re = 39 and >90% efficiency at Re = 15~55. At Re<15, limited inertial effects on microparticles cause insufficient inertial migration which affects focusing efficiency. At Re>55, focusing efficiency decreases due to additional equilibrium positions emerging near the side walls.

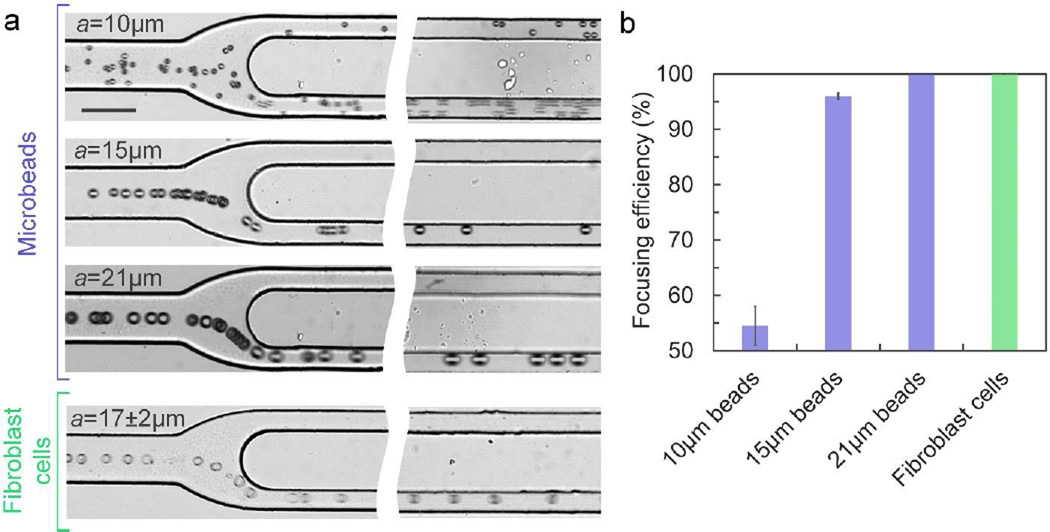

3D focusing of different sized polymer beads and cells

The presented inertial microfluidic focuser can precisely focus microbeads or cells with different diameters into a 3D single position. Using a device with dimensions wu×hu×Lu=75µm×50µm×25mm, wd×hd×Ld=30µm×50µm×10mm and R2/R1=3, microbeads with diameter a ≥ 15µm can be successfully focused into a single position at Re =39 with efficiency η ~99% (Fig. 5). Focusing of larger microbeads exhibits a slightly higher efficiency due to larger inertial lift forces leading to tighter inertial focusing in the given channel dimension. For microbeads with diameter a ≤ 10µm, the device with the current dimensions exhibits only η = 55% focusing efficiency. As shown in Fig. 5a, the 10µm microbeads were insufficiently focused into a band in upstream LAR channel caused by the significantly reduced inertial lift forces on smaller particles (FL~a4)21, 34, 42 leading to much slower inertial migration towards the equilibrium positions (UL~a3)21. The focusing of smaller microbeads can be easily improved by designing longer upstream LAR channel to allow equilibration before entering the downstream HAR channel or designing smaller channel cross-section to enhance the inertial lift forces (FL~Dh−2) for faster migration (UL~Dh−2)34.

Figure 5.

3D focusing of different sized polymer beads and cells. (a) Experimental observation of focusing of different-sized polymer microbeads and fibroblast cells at Lu=25mm and Ld=10mm at Re=40. The scale bar is 75µm. (b) Quantitative measurement of focusing efficiency of different-sized polymer microbeads and fibroblast cells at Re=40 (n=3).

The inertial microfluidic focuser can also focus cellular samples with high efficiency. Mouse fibroblast cell suspension with a diameter of 17.3±2.2µm and a concentration of 3.4×105/mL was introduced into the device at Re=40. Although cells are deformable, heterogeneous and not as spherical as polymer microbeads, the device can successfully align them into the single position shown the same focusing trajectory as polymer microparticles (Fig. 5a). It indicates robustness of the 3D focusing using inertial lift forces in this simple device. Quantitative measurements further indicate that the focusing efficiency is ~100%, suggesting that device with optimized systematic parameters can focus real cellular samples into single-position with high efficiency (Fig. 5b).

Sheathless flow cytometry with high throughput and efficiency

The inertial microfluidic single-position focuser easily lends itself to integration with flow cytometry for counting of fluorescently-labeled microbeads and cells with high efficiency and throughput, without the use of sheath flow, secondary flow or external force field (Fig. 6a). Fluorescently-labeled microbeads or cells were excited using a laser through a 20× objective with a spot size of ~10µm. The laser spot was focused at the half height of downstream channel 1 near inner side wall at Ld1=10mm. Single-position focused microparticles pass the laser spot at the same horizontal and vertical position, eliminating the variation or miscounting induced by different spatial position. Emitted light from microparticles was detected with a PMT, and further amplified and recorded with a LABVIEW data acquisition system. A representative signal is shown in Fig. 6b, with each voltage spike representing a microparticle passing the excitation laser spot. Distribution of the signal potential shows a Gaussian-like distribution with a coefficient of variation of CV = 7% indicating the high precision of the 3D focusing in the device (Fig. 6c). In comparison, the signal acquired using a normal LAR channel has a larger CV > 13% due to microparticles being focused in two positions at different focal planes (Fig. 6d). A throughput of 2200/s was demonstrated with CV=11% for 9×105/mL concentration of 15µm beads (Fig. 6e–f). The increase in CV is caused by bead aggregation and interparticle interactions, which are observed mainly in samples at higher concentrations. Notably, although only observed in a time window lasting 2×10−4s, the throughput reaches ~40,000/s at which the system is still able to detect and differentiate focused beads (Fig. 6g).

Figure 6.

Sheathless flow cytometry with high throughput and high efficiency. (a) Schematic of the custom counting system. (b) Signals of counting microbeads with diameter of 15µm during a 1s time window. (c) The voltage distribution of the signals acquired using the single-position focuser. The inset schematic illustrates cross-section of the downstream channel 1. The green dot represents particle. The blue triangle represents the laser. (d) The voltage distribution of the signals acquired in a normal LAR channel. The inset schematic illustrates cross-section of the LAR channel. The green dot represents particle. The blue triangle represents the laser. (e) Counting of microbeads with high throughput. (f) The voltage distribution of the counting signals. (g) Observation of extreme throughput in 2×10−4s time window. (h) Illustration of fluorescently labeled fibroblast cell counting during 1s time window. (i) Fluorescent and bright field images of cells after running the cytometry experiments. (j) Bright field image of cells after culturing for 2 days. The scale bars in (i) and (j) are 100µm.

The inertial microfluidic sheathless flow cytometer can precisely count cellular samples without damage. Fluorescently-labeled mouse fibroblast cells (3.4×105/mL) were introduced into the device at Re = 40 and counted using the same setup. Approximately 8,500 cells were detected during a 10s time window, indicating a throughput of ~850 cells/s. Figure 6h shows a representative signals during a 1s time window. Although the fibroblast cells can be focused precisely at the single position with ~99% efficiency (as shown in Fig. 5), the recorded signals exhibit a relatively larger CV = 58%. This large variability is attributed in part to variation in size, approximately 13%, and the resulting small variations in the equilibrium position of focused cells. The largest component in the variability (approximately 45%) arises from the nonuniform fluorescent labeling, as observed by analyzing fluorescent images of cells in a hemacytometer. We noted similar variability in our earlier work with SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells38.

To assess compatibility of the system with cellular samples, we measured recovery rate and viability of cells after performing the sheathless cytometry experiments. The recovery rate, which is defined as the ratio of the concentration of cells after and before the process, is measured to be ~99% (n = 3). This result suggests that cells can pass the device without lysis or clogging. Further, cells can still emit fluorescent light after passing the device, confirming the intact cell structure (Fig. 6i). The cells were further cultured for 2 days to test the viability. All cells appeared to function and replicate normally, suggesting high viability (Fig. 6j).

Discussion

The simplicity of the focusing mechanism and device geometry bring flexibility to the design. Designing smaller cross-section leads to shorter focusing length, thus can benefit the miniaturization of the device. For example, the total length of the device for single-position focusing of 7µm diameter particles is calculated to be 80mm using cross-section dimension D3. One can easily shrink the footprint by designing a device with smaller dimension D1 which shortens the length to ~20mm. On the other hand, when processing delicate samples such as cells, one can design larger channel cross-section to reduce magnitude of inertial lift forces acting on cells (FL~Dh−2). Although the total length of channel will increase, reducing stress due to the inertial lift forces can minimize damages or lysis, which is beneficial for focusing biological samples.

Although cellular samples are generally heterogeneous and have wide size distribution, single-position focusing of cellular samples using this device still exhibits ~99% efficiency with high precision. This is because the device only uses inertial lift forces without the need to balance by additional forces such as Dean drag force or electric field force. Previous devices such as microstructure array39, 40 and spiral devices38 achieved the single-position focusing by the balance of inertial lift forces and secondary flow-induced drag force. However, the magnitude of these forces changes with cell diameter at different rate. This feature affects the focusing of different sized cells, leading to defocusing38 and decreasing of the focusing efficiency39. In the presented device, the only design criteria for focusing cells or microparticles is to have a sufficiently long focusing channel so that all the cells can migrate into equilibrium positions.

We demonstrated sheathless cytometry with throughput of 2,200/s for polymer beads and 850/s for cells at a volumetric flow rate of 0.15mL/min. The throughput can be increased further using two approaches. The first is to simply increase concentration of the samples. This approach was used by Chung et al.39, 40 to demonstrate focusing of 10µm diameter microbeads with throughputs of ~13,000 beads/s to 36,000 beads/s. Although using high concentration sample can directly increase the throughput an order of magnitude or higher, it may lead to potential problems such as interparticle interaction and channel clogging. The second approach is to design a device with larger cross-section. Since Re remains at the same order of magnitude (Re = 40), higher volumetric flow rate (Q~Re(w+h)) has to be used to reach the optimal Re which leads to higher throughput. For example, the flow rate used in D2 is 0.15mL/min for Re = 40. In a device with cross-section D4, a flow rate of 0.21mL/min is required for Re = 40 leading to 1.4× increasing in throughput.

In this work, we demonstrate sheathless cytometry of cellular samples with high recovery rate and viability. The compatibility with biological samples stems from the simplicity of the driving forces and the channel geometry. From the principle aspect, the device eliminates the use of sheath flow, secondary flow (and force) and external force, and only uses inertial lift forces to achieve single-position focusing. Thus it minimizes the possible damage on cells caused by these extra flow and forces during the focusing process. From the geometry aspect, the device only consists of two sections of straight channel eliminating the use of microstructures such as pillar array. This feature minimizes the possible clogging or damage as cells travel through these geometries.

In conclusion, we present a microfluidic device with simple straight geometry for ordering microparticles and cells into a single-position with high throughput and efficiency. Our approach uses the inertial lift force as the only driving force to guide microparticles and cells into a single focusing position without using sheath flow, secondary flow and other external forces which are often used by other focusing techniques. Due to the straight channel geometry, the device can be easily designed and modified using our two-stage inertial migration model for focusing of different sized microbeads or cells. We demonstrated focusing of microbeads and cells with efficiency as high as ~99%. We integrated this device with a laser counting system to form a powerful sheathless flow cytometer for counting of microbeads and cells with high throughput and accuracy. Using the system, we demonstrated counting of microbeads with a throughput of >2000beads/s. With further optimization, we believe the count could can be increased much further, as demonstrated by the repeated 0.2 ms windows of throughput in the ~40,000 beads/s. We also demonstrated accurate counting of cells with ~100% recovery rate and ~100% viability implying the delicacy and compatibility of this approach for focusing and counting of real biological samples. We envision this 3D single-position focuser will serve as a powerful microfluidic component for cytometry as well as sorting applications by providing precise and delicate fluidic ordering and alignment of cells.

Methods

Microfabrication

We used standard soft lithography process to fabricate microchannels in polydimethysiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning). We used a 50 µm high master formed in MX5050 dry film photoresist (Microchem Corp.). A mixture of PDMS base and curing agent (10:1 ratio) were poured on the master, vacuum degassed for 120 minutes and then, cured for 4 h on a 60 °C hotplate. The cured PDMS devices were peeled off the master, and inlet/outlet ports were punched with a 14 gauge syringe needle. PDMS was bonded to a standard glass slide using a hand-hold plasma surface treater (BD-20AC, Electro-Technic Products, Inc.). We fabricated devices with different resistance ratio R2/R1 by varying the length of downstream channel 1 and channel 2. The device with R2/R1=∞ was fabricated by selectively punching only the outlet of channel 1. Since the flow can only exit through channel 1 but not channel 2, this arrangement creates R2/R1=∞.

Preparation of microbeads suspensions

We diluted FITC-labeled polymer microbeads with diameter of 15 µm (Bangs Laboratories Inc.) into deionized water to form a suspension with concentration of 4 × 104 beads/mL. To investigate the focusing of different sized microbeads, suspensions of microbeads with diameters at 10µm, 15µm and 21µm (Bangs Laboratories Inc.) were also prepared at concentration of 4 × 104 beads/mL. We added Tween-20 at 0.1% v/v (Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to the particle suspensions as stabilizer to avoid clogging issue. For flow cytometry experiments, we prepared FITC-labeled polymer microbeads with diameter of 15 µm at two concentrations. For demonstration of the counting (Fig. 6b–d), we used concentration of ~3.2×104 beads/mL. For demonstration of high-throughput counting (Fig. 6e–g), we used concentration of 9×105 beads/mL.

Preparation of cell samples

NIH/3T3 fibroblast cells were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Lonza, USA) with HEPES and L-Glutamine, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (gibco, USA). Cells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Medium was changed after 72-hours, and every 48 hours thereafter after washing with PBS (3×2 mL). NIH/3T3 fibroblast cells were labeled with Cell Tracker Green CMFDA (5µM, Invitrogen, USA) in IMDM without serum and incubated for 30 minutes. Cells were suspended by incubation with 0.25% trypsin for 3–5 minutes at 37°C under 5% CO2. Once suspended, cells were spun at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes. Supernatant was exchanged with IMDM to a final volume of 1mL. Cell density was measured using a brightline hemacytometer.

Device operation and microscopic imaging

We first loaded a syringe with particle suspension and connected it to the device by using a 1/16” peek tubing (Upchurch Scientific) with proper fittings (Upchurch Scientific). We pumped particle solution into devices with designed flow rate using a syringe pump (Legota 180, KD scientific). To visualize trajectory of particle in bright-field, we used an inverted epi-fluorescence microscope (IX71, Olympus Inc.) equipped with 20× objective and a 12-bit high-speed CCD camera (Retiga EXi, QImaging). We set the exposure time to minimum value (10 µs) and sequentially took 300 images with minimum time interval. By stacking images in ImageJ, we established a complete view of particle motion. To capture fluorescence images of particle focusing, we used the same microscope while setting the exposure time to 100 ms and sequentially taking 20 images. The images were then stacked and pseudo-colored in ImageJ.

Custom laser counting system

The custom laser counting system consists of an inverted microscope (TE2000U, Nikon Inc., Melville, NY, USA) with a 20× objective. Both FITC-labeled microbeads and cells were excited using a 488nm argon laser (50mW, CVI Melles Griot, Albuquerque, NM, USA) with corresponding neutral density filter (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA) for power adjustment. A photomultiplier tube (H6780-20, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) was used to collect emitted light. The signal collected from the PMT was processed with a current-to-voltage preamplifier (SR570, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and then further recorded using a custom LabVIEW data acquisition system (NI PCI 6036E National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

Data analysis

We measured the linescans of the fluorescent intensity peaks using ImageJ (Fig. 4b). We measured the focusing efficiency of microbeads and cells by manually counting microbeads or cells in at least 100 images captured at Lds=10mm (Fig. 4a and Fig. 5a). At least 600 microbeads or cells were counted for each experiment. Focusing efficiency was calculated as the number of beads in the expected position over the total number of beads. Each experiment was repeated at least three times for every data point.

Numerical models

We modeled devices using a commercial computational fluid dynamics software CFD-ACE+ (ESI-CFD Inc., Huntsville, AL). The module we used to solve for fluid motion in the geometry is FLOW. The physical properties of water was applied to the fluid in the simulation (density ρ = 1000kg/m and dynamic viscosity µ = 10−3 kg/m-s). The velocity of x-direction (m/s) calculated from the flow rate was applied to initial inlet velocity. We set convergence limit for mass fraction to 10−6 and run simulation for 3000 time steps to ensure simulation convergence. We analyzed simulation results in CFD-VIEW. We added 25 streamlines with equal distances across the channel width to visualize streamline distribution.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by funds provided by the Ohio Center for Microfluidic Innovation (OCMI) and NIH grants R01EB010043 and R01GM112017.

References

- 1.Xuan X, Zhu J, Church C. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2010;9:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolan JP, Sklar LA. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:633–638. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toner M, Irimia D. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2005;7:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.011205.135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karabacak NM, Spuhler PS, Fachin F, Lim EJ, Pai V, Ozkumur E, Martel JM, Kojic N, Smith K, Chen P, Yang J, Hwang H, Morgan B, Trautwein J, Barber TA, Stott SL, Maheswaran S, Kapur R, Haber DA, Toner M. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:694–710. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Nawaz AA, Zhao Y, Huang P, McCoy JP, Levine SJ, Wang L, Huang TJ. Lab Chip. 2014;14:916–923. doi: 10.1039/c3lc51139a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi J, Yazdi S, Steven Lin S, Ding X, Chiang I, Sharp K, Huang TJ. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2319–2324. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20042a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi J, Mao X, Ahmed D, Colletti A, Huang TJ. Lab Chip. 2008;8:221–223. doi: 10.1039/b716321e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu H, Doh I, Cho Y. Lab Chip. 2009;9:686–691. doi: 10.1039/b812213j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin C, Lee G, Fu L, Hwey B. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2004;13:923–932. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald MP, Spalding GC, Dholakia K. Nature. 2003;426:421–424. doi: 10.1038/nature02144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Fujimoto BS, Jeffries GDM, Schiro PG, Chiu DT. Opt. Express. 2007;15:6167–6176. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.006167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott R, Sethu P, Harnett CK. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2008;79:046104. doi: 10.1063/1.2900010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao X, Nawaz AA, Lin SS, Lapsley MI, Zhao Y, McCoy JP, El-Deiry WS, Huang TJ. Biomicrofluidics. 2012;6:024113. doi: 10.1063/1.3701566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nawaz AA, Zhang X, Mao X, Rufo J, Lin SS, Guo F, Zhao Y, Lapsley M, Li P, McCoy JP, Levine SJ, Huang TJ. Lab Chip. 2014;14:415–423. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50810b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi S, Song S, Choi C, Park J. Small. 2008;4:634–641. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hur SC, Tse HTK, Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2010;10:274–280. doi: 10.1039/b919495a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Carlo D, Irimia D, Tompkins RG, Toner M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:18892–18897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704958104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hur SC, Choi S, Kwon S, Carlo DD. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;99:4527. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martel JM, Toner M. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3340. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhagat AAS, Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Papautsky I. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1906–1914. doi: 10.1039/b807107a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhagat AAS, Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Papautsky I. Phys. Fluids. 2008;20:101702. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan G, Wu L, Bhagat AA, Li Z, Chen PCY, Chao S, Ong CJ, Han J. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1475. doi: 10.1038/srep01475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou HW, Warkiani ME, Khoo BL, Li ZR, Soo RA, Tan DS, Lim W, Han J, Bhagat AAS, Lim CT. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1259. doi: 10.1038/srep01259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hur SC, Henderson-Maclennan NK, McCabe ERB, Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2011;11:912–920. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00595a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MG, Choi S, Park J. J. of Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:4138–4143. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mach AJ, Kim JH, Arshi A, Hur SC, Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2827–2834. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20330d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nivedita N, Papautsky I. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7:054101. doi: 10.1063/1.4819275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Zhou J, Papautsky I. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7:044119. doi: 10.1063/1.4818906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Yan S, Sluyter R, Li W, Alici G, Nguyen N. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4527. doi: 10.1038/srep04527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J, Kasper S, Papautsky I. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2013;15:611–623. doi: 10.1007/s10404-013-1176-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Giridhar PV, Kasper S, Papautsky I. Lab Chip. 2013;13:1919–1929. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50101a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3038–3046. doi: 10.1039/b912547g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amini H, Lee W, Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2014;14:2739–2761. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00128a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J, Papautsky I. Lab Chip. 2013;13:1121–1132. doi: 10.1039/c2lc41248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martel JM, Toner M. Annu. Rev. of Biomed. Eng. 2014;16:371–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-121813-120704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segré G, Silberberg A. Nature. 1961;189:209–210. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oakey J, Applegate RW, Arellano E, Carlo DD, Graves SW, Toner M. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:3862–3867. doi: 10.1021/ac100387b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhagat AAS, Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Kaval N, Seliskar CJ, Papautsky I. Biomed. Microdevices. 2010;12:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung AJ, Gossett DR, Di Carlo D. Small. 2013;9:685–690. doi: 10.1002/smll.201202413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung AJ, Pulido D, Oka JC, Amini H, Masaeli M, Di Carlo D. Lab Chip. 2013;13:2942–2949. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41227j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Bhagat AAS, Kumar G, Papautsky I. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2973–2980. doi: 10.1039/b908271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asmolov ES. J. Fluid Mech. 1999;381:63–87. [Google Scholar]