Abstract

This article presents the rationale for and description of a promising intervention, Time for Living and Caring (TLC), designed to enhance the effectiveness of respite services for family caregivers. It is guided by the theoretical principles of the Selective Optimization with Compensation (SOC) model, which individually coaches caregivers on how to assess their personal circumstances, identify their greatest needs and preferences, and engage in goal setting and attainment strategies to make better use of their respite time. Focusing on respite activities that match caregivers’ unique needs is likely to result in improved well-being. We report on a pilot study examining TLC’s feasibility and potential benefits and how caregivers viewed their participation. While additional research is needed to test and refine the intervention, we need to find more creative ways to enhance respite services.

Until you value yourself, you will not value your time. Until you value your time, you will not do anything with it. (Peck, 2011)

The primary purpose of this article is to present the rationale for and description of a promising theoretically-based intervention, designed to enhance the effectiveness of respite services for family caregivers. Respite, or having time away from providing direct care to a person needing care, has been identified as one of the most desired and needed forms of assistance for family caregivers (Evercare and the National Alliance for Caregiving, 2009). Yet, there has been little documented research to show that respite has consistent and positive benefits for caregivers (ARCH National Respite Network and Resource Center, 2007). We will argue in this article that a key mechanism missing in the relationship between respite and caregiver outcomes is how caregivers use their time while receiving this service. Furthermore, we propose a unique intervention model that capitalizes on the role of time-use and respite activities in this relationship. The intervention is based on the Selective Optimization with Compensation (SOC) model (Baltes & Baltes, 1990). While this conceptual model has been widely used in interventions and research related to human development, aging, and adjustments to losses, it has not yet been used to guide interventions for caregivers.

Before we describe the features of the intervention based on the SOC model, we discuss the current national crisis related to caregiving that makes it imperative that we develop and test strategies to help alleviate some of the detrimental impact of the crisis. We then propose an explanation for why respite research has not revealed the expected positive results and describe how our intervention examines an important but missing component in this body of research. We also briefly present results from our previous studies that show considerable promise for the intervention model we have developed and plan to test on a much larger scale.

FAMILY CAREGIVING IN THE UNITED STATES

The challenge of providing care to a rapidly growing number of older adults in the United States has entered a crisis phase. In 2009, there were over 42 million persons in the United States providing care for older family members (Feinberg, Reinhard, Houser, & Choula, 2011). However, the numbers of available caregivers is not keeping pace with the increasing numbers of those who need care (International Longevity Center, 2006; Lund, Utz, Caserta, & Wright, 2009; Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013). As is well known, the aging of the baby boomers is creating a dramatic shift in the age composition of the U.S. population (Colby & Ortman, 2014). In 2016, 8,000 of the 76 million baby boomers will be turning age 70 every day, and this trend will continue for 18 years and beyond as they move into their 80s and 90s (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). In other words, the large baby boom generation is beginning to transition from being caregivers to care recipients (Redfoot et al., 2013). By 2056, the population over 65 years and over is projected to become larger than the population under 18 years (Colby & Ortman, 2014). This is problematic because advanced age is most often associated with increased frailty, dependency, and need for assistance (Bault, 2012). As our population ages, the need for caregiving inevitably increases.

Simultaneously, as a result of decreasing family size, increasing divorce rates, geographic mobility of adult children, and increased workforce participation (Brown & Lin, 2012), there is a shrinking pool of available, capable, and willing caregivers in the younger generations. Those that are available to provide caregiving to older family members or friends often experience physical and mental health declines, financial hardships, and personal sacrifices associated with meeting the expectations and tasks of being primary caregivers (APA, 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003; Redfoot et al., 2013). Taken together, the United States is facing a greater demand for caregivers, less supply of potential caregivers, and as a result increasing burden and sacrifice of those who are able to take on a family caregiving role. Research has consistently shown that family caregivers and friends are now providing informal care without adequate support services (Reinhard, Levine, & Samis, 2012). Over the next 30 to 40 years, as the shrinking “caregiver support ratio” heads into a “free fall” (Redfoot et al., 2013, p. 7), the family caregiving crisis in the United States will only worsen. Thus, it is imperative that we develop new strategies to deliver more cost-effective and impactful support services to existing caregivers, including those who are friends or relatives of the care recipients.

RESPITE SERVICES

Respite (time away from caregiving responsibilities and tasks) has been identified as one of the most needed and desired services and potentially one of the most promising strategies to preserve and potentially improve the well-being and quality of life of caregivers (Evercare and the National Alliance for Caregiving, 2009). Respite is expected to provide caregivers the freedom and support they need, by allowing them time to tend to their own wellness, social and family relationships, and other aspects of their daily lives that have been neglected due to their overwhelming caregiving tasks (Evans, 2013). The establishment of the “National Family Caregiver Support Program” in the Older American Act Amendments of 2000 and the Lifespan Respite Care Act of 2006—both of which expanded and enhanced respite care services to families—provides documentation that respite is a critical component to addressing the national caregiving crisis (Lund et al., 2009).

Problematic, however, is that after 35 years of research on the effectiveness of respite, we see only moderately positive, and often inconsistent and mixed results regarding its benefits to caregiver well-being (ARCH National Respite Network and Resource Center, 2007; Kosloski & Montgomery, 1993; Sörensen, Pinquart, & Duberstein, 2002; Zarit, Stephens, Townsend, & Greene, 1998). One of the most widely cited studies examining the use of respite concluded that caregivers need to use respite regularly, at least 2 days per week and in blocks of time to have a chance to be effective (Zarit et al., 1998). Research to date, however, has been limited by a lack of rigorous and controlled research designs, homogeneous samples, lack of comparison groups, and the failure to focus on how to make respite more effective (Evans, 2013). The National Institute of Health (NIH) funded two significant sets of caregiver intervention studies: Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) I (1996-2000), which consisted of nine intervention approaches to find strategies to reduce caregiver stress, and the five-site REACH II studies (2001-2006; Belle, Burgio, Burns, Coon, Czaja, Gallagher-Thompson, et al., 2006; Schulz, Belle, Czaja, Gitlin, Wisniewski, Ory, et al., 2003). Together, this major research effort examined self-care, safety, social support, emotional well-being, management of behavioral problems, skill training, telephone-based support, behavior modification, family therapy, computerized telephone communication, coping classes, and support groups (Belle et al., 2006; Schulz, Belle, et al., 2003). Most of the REACH interventions produced modest, but limited benefits for caregivers. Also, surprisingly, none of the studies examined the effectiveness of respite services (Belle et al., 2006; Schulz, Belle, et al., 2003).

While skepticism about respite justifiably remains, we cannot afford to neglect its considerable promise. At the very least, there is a need to identify and examine mechanisms through which respite can more effectively provide its intended benefits to both care recipients and the growing numbers of family caregivers. We need to move beyond studies that only compare respite users to non-users, and instead, ask questions about new strategies to make respite more effective. We suggest designing studies to compare caregivers who use respite services for different purposes and engage in different respite activities so that the focus is on making respite more effective. Also, Greenwood, Habibi, and Mackenzie (2012) suggested that we need greater clarity about what respite is intended to achieve and clear evidence of a positive impact of respite. These are considered high priority research aims by a recently-formed expert panel (2013-2015) sponsored by the Administration on Aging (AoA) and the National Respite Network and Resource Center (Expert Panel on Respite Research, 2013). The expert panel has been asked to clarify the definition of respite, identify gaps in research on respite, and make suggestions for future research. Two of the authors of this manuscript serve on this expert panel.

After nearly 30 years of our own research on family caregivers and the need for respite, we have come to the conclusion that although respite has been reported by caregivers as the most needed service, it should not be mistakenly assumed to have automatic positive outcomes for caregivers (Caserta, Lund, Wright, & Redburn, 1987; Evercare and the National Alliance for Caregiving, 2009; Shope, Holmes, Sharpe, Goodman, & Izenson, 1993). In one of our own pilot studies, which we discuss in more detail in the next section of this article, we unexpectedly found that 46% of the caregivers were not very satisfied with how they had spent their respite time (Lund et al., 2009). In fact, some caregivers engaged in activities that increased their stress and/or resulted in frustration. This dissatisfaction and frustration was the result of wasted opportunities for more beneficial uses of time that could have been targeted to their specific needs and desires. Table 1 lists some of the comments expressed by caregivers, illustrating their dissatisfaction with respite time.

Table 1.

Caregivers’ Dissatisfaction with Respite Time

|

More importantly, this pilot study found that dissatisfaction with respite time-use was associated with higher caregiver burden and depression (Lund et al., 2009; Utz, Lund, Caserta, & Wright, 2012). Many years ago, Seleen (1982) also reported that life satisfaction was higher when older adults actually spent their time doing desired activities. However, no research to date, other than our own, has examined the relationship between what caregivers do during respite and how that affects their well-being. In short, while there has been an expansion of the availability of respite services for caregivers in the United States, there is minimal evidence on how to maximize the potential benefits that caregivers receive from using them.

A TAILORED INTERVENTION TO MAKE RESPITE MORE EFFECTIVE: TIME FOR LIVING AND CARING

Based on these pilot findings described previously, we have developed an intervention which we call Time for Living and Caring (TLC) that addresses this missing component—what caregivers do during their respite time. The intervention title refers to the need for caregivers to spend time focusing on their personal lives, as well as their caregiving responsibilities. The TLC intervention individually coaches caregivers on how to assess their personal circumstances and then how to best utilize their respite time through goal-setting and goal-attainment strategies. The individualized nature of this intervention is important, because other research has suggested that there is no specific type of time-use that will be most effective for all respite users, as it needs to match the caregiver’s profile, culture, and other caregiving circumstances (Bourgeois, Schulz, & Burgio, 1996; Whitlatch, Feinberg, & Sebesta, 1997). The intervention we propose should be inclusive of a broad and diverse range of caregivers representing various racial, ethnic, religious, and sexual orientation groups because it is based on an individually tailored approach that considers the caregiver’s own unique background characteristics, preferences, and desires (Coon, 2003; Mittleman, Epstein, & Pierzclala, 2002). Those who would participate in our intervention have already determined that using respite services is culturally acceptable to their norms because they would have already made that decision. Also, the intervention could be implemented as caregivers first begin to use respite services and prior to establishing any patterns of what they might do during their respite time. However, we have no reason to expect that the intervention would not be effective for caregivers who already have been using respite for months or even years. Caregiving is a very dynamic process with frequent changes occurring in caregiver circumstances that could easily disrupt patterns in caregiver behaviors. Therefore, we would encourage the implementation of our proposed intervention for caregivers just beginning to use respite, but also for those who have been users for any amount of time. Caregivers with already established patterns of respite-time use could still benefit from an intervention that begins with an assessment of their needs and desires and encourages a good match between an assessment and behavior plans to best meet their perceived needs. Also, the source and type of respite, such as in-home, adult day center, extended care, short-term, or long-term should not matter. The intervention is only based on the assumption that when caregivers use any type of respite they will benefit the most if they use their respite time to best meet their own specific needs. We now turn attention to the conceptual model that guides the intervention.

The intervention was developed according to the theoretical principles of Selective Optimization with Compensation (SOC), which is a theoretical model used to explain how people adjust to age-related limitations, deficits, and potential losses (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Riediger, Freund, & Baltes, 2005; Roberto, Husser, & Gigliotti, 2005; Stawski, Hershey, & Jacobs-Lawson, 2007). The SOC framework is a well-developed model supported by large quantities of empirical inquiry (George, 2012). It has been most influential in generating research related to active life management and its relationship to adjustment and well-being (Freund & Baltes, 2002). Applications of SOC usually involve an assessment of a person’s needs and desires, which then can be used to guide a goal-setting process, whereby individualized goals are selected, and a strategy to optimize goal attainment is pursued. The compensation element in the model emphasizes the importance of taking into account potential obstacles and limitations that would make a selected goal impractical or unfeasible.

SOC has been called a useful theoretical framework for creating intervention programs that foster successful development and aging and that can be targeted to specific populations (Riediger, Li, & Lindenberger, 2006). The SOC model is directly applicable to family caregivers, because their caregiving circumstances usually result in losses of time, social relationships, finances, and other aspects of their lives. Caregiving disrupts and makes life management more difficult and may result in long-term negative consequences to caregiver’s life course development and overall well-being. In the specific context of respite time-use, the SOC model would argue that caregivers should “selectively” focus their attention and efforts on activities of greatest importance or based on their most critical needs, formulate goals that will “optimize” the attainment of their desired goals, while “compensating” for the practical limitations of their current circumstances. Consistent with SOC objectives, the TLC intervention aims to help caregivers maximize gains from carefully selected and prioritized respite time-use, and to minimize further losses that can result from a less satisfying use of respite time. As mentioned previously, this intervention is sensitive and respectful of caregivers from very diverse cultural and sexual orientations because the assessment, goal identification, goal setting, and goal optimization processes are guided by the unique features of each caregiver (Coon, 2003; Mittleman et al., 2002). Based on the SOC model there is no reason for excluding any caregivers based on their unique cultural characteristics.

Description of Intervention

The TLC intervention would be provided most effectively to caregivers in an individualized manner by specially trained persons who already have professional experience or positions related to service delivery to caregivers, families, and/or older adults such as geriatric care managers, social workers, gerontological nurses, mental health professionals, and those with similar academic and employment backgrounds and experience working with caregivers or caregiving families. Other professionals such as life coaches, peer mentors, and support group leaders could be trained to deliver the intervention. The preferred strategy would be to begin with three to four weekly sessions, followed by three to four biweekly sessions, and a phasing-out period of two to three monthly sessions. The intensity and frequency of facilitator contact should be decreased over time because the participant should become more competent in completing the SOC tasks independently. Furthermore, in an effort to provide choice and to accommodate unique caregiver needs, caregivers should be able to individually select the total number of intervention sessions. For example, they could have a total of 8 to 11 sessions over 5 to 6 months. This dosage is in-line with other common caregiver interventions (Eisdorfer, Czaja, Loewenstein, Rubert, Arquelles, Mitrani, et al., 2003; Schulz, 2000; Schulz, Burgio, Burns, Eisdorfer, Gallagher-Thompson, Gitlin, et al., 2003; Schulz, Gallagher-Thompson, Haley, & Czaja, 2000; Schulz, Martire, & Klinger, 2005). Caregivers typically would begin with in-person sessions, but could elect at the end of the weekly sessions to have some contacts delivered over the phone. Past research has found that, above all, caregivers want to have options in how supportive services are made available to them so that their daily responsibilities are best accommodated (Colantonio, Kositsky, Cohen, & Vernich, 2001; Feinberg & Houser, 2011; Ploeg, Biehler, Willison, Hutchison, & Blythe, 2001).

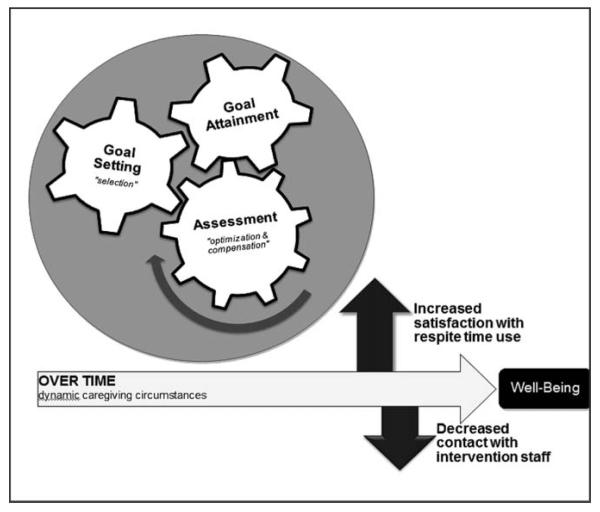

As shown in Figure 1, the intervention would consist of an ongoing process of three interrelated tasks: assessment, goal setting, and goal attainment. Over time, direct staff intervention would decrease, as the individual becomes more accustomed to completing these tasks him or herself, while satisfaction with respite time-use would likely increase as a result. Based on our previous pilot work, we also expect this to result in more positive perceptions of caregiving experiences and potentially improved overall well-being for caregivers (Lund et al., 2009; Utz, Caserta, & Lund, 2012).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model linking the components of the Time for Living and Caring intervention (assessment, goal setting, goal attainment) with the Selective, Optimization, and Compensation Theoretical Principles.

In Figure 1, the assessment gear was intentionally drawn as the largest gear with an arrow, to illustrate that intervention is driven primarily by the initial and ongoing process of assessment, whereby one’s individual and dynamic needs, circumstances, priorities, and resources are discussed and inventoried. During an assessment, a facilitator would discuss with the participant his/her current satisfaction with respite time-use, as well as activities enjoyed but potentially sacrificed due to caregiving responsibilities. The assessment also includes standardized measure of caregiver burden that identifies five separate dimensions of burden: (a) time dependence, (b) developmental, (c) physical health, (d) social relationships, and (e) emotional health (Caserta, Lund, & Wright, 1996; Novak & Guest, 1989). Effectively planned respite time could provide opportunities for caregivers to engage in their desired activities or those directly aimed at alleviating specifically targeted sources of burden. In this sense, the assessment leads naturally to a goal setting process. Using the terminology of the SOC model, the assessment helps guide caregivers in the identification and prioritization of time-use goals (selection of goals), by requiring them to be aware of unique limitations in resources (need for compensation) and forcing them to consider ways to remove obstacles and make goal attainment more likely (facilitates optimization).

Table 2 describes hypothetical caregiver scenarios that might arise during the assessment and subsequent goal setting stages of the intervention. Selection of individualized goals requires prioritizing and advanced planning to insure that the goal or activity can take place during the desired respite time, especially if the desired activities involve the participation of others, or making advanced appointments (Gignac, Cott, & Badley, 2002; Hoppmann, Poetter, & Klumb, 2013). Thus, during this phase of the intervention, facilitators would remind caregivers that they must select and define goals (one to three per session) that are personally important, but also realistic and attainable. We suggest setting no more than three goals per session in order to provide sufficient focus and importance on the attainment of each goal.

Table 2.

Caregiver Scenarios Describing the Assessment Phase of the Intervention that Leads to Initial Goal Selection

|

The compensation strategy of the SOC model reminds caregivers to consider the limitations and restrictions in his/her life circumstances and resources that may not be amenable to change. Accordingly, selection of time-use goals may need to be modified based on these considerations, allowing a more successful optimization of goal attainment. Previous literature documents that goal setting can facilitate behavior change even when the person may be reluctant because the process of specifying goal intentions and developing realistic and individualized implementation plans has positive impacts on subsequent behavior (Gollwitzer, Gawrilow, & Oettingen, 2010; Judge, Bass, Snow, Wilson, Morgan, Looman, et al., 2011; Vancouver, Weinhardt, & Schmidt, 2010; Webb & Sheeran, 2006). A meta-analysis of 94 studies revealed that having a clearly stated goal, as well as a realistic plan of action in place to achieve it, were positively related to successful goal attainment (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). Using the same hypothetical caregiver examples from Table 2, Table 3 presents hypothetical scenarios detailing how the SOC strategies might be used by the facilitator to help coach caregivers to set realistic time-use goals, and ensure that plans for implementation are developed. In other words, the initial goals may need to be revised in order to maximize successful goal attainment.

Table 3.

Caregiver Scenarios Illustrating How Compensation and Optimization are Considered When Setting Time-Use Goals

|

The third feature of the intervention is related to goal attainment. This process involves an evaluation of whether the stated goals were successfully accomplished. If the initial goals were met, it is assumed that the caregiver was able to achieve all three principles of the SOC model—that is, they selected realistic time-use goals, compensated for personal constraints, and optimized his/her ability to achieve the time-use goals. If a specific goal was not met, the facilitator will help the caregiver identify potential reasons why it was not achieved. These reasons might be that the goal was unrealistic, unanticipated barriers arose, the initial plan to address barriers was inadequate, and/or the caregiver’s needs, priorities, circumstances, or resources had changed. Upon review of goal attainment, regardless of whether the specific time-use goal was met or not, the facilitator will help the caregiver identify new goals, repeat existing ones, or revise former goals using the same assessment and goal setting strategies that were used previously—setting the gears of assessment, goal setting, goal attainment into motion once more. Using the same hypothetical scenarios outlined above, Table 4 illustrates how the goal attainment phase of the intervention will force the caregiver to review and re-set future goals, as well as re-consider the constraints of personal circumstances and resources, in order to maximize their future goal-attainment and hopefully their satisfaction with future respite time-use.

Table 4.

Caregiver Scenarios Detailling How the Goal Attainment Phase Leads to the Cyclical or Iterative Nature of the Intervention

|

Given these three intertwined and iterative components of assessment, goal setting, and goal attainment, the TLC intervention is modifiable based on individual circumstances and changing caregiver situations (Belle et al., 2006; Hong, 2010; Schulz, Burgio, et al., 2003). This intervention also has the potential to help caregivers meet multidimensional needs (Carnevale, Anselmi, Busichio, & Millis, 2002; Grant, Elliott, Giger, & Bartolucci, 2001; Paun, Farran, Perraud, & Loukissa, 2004; Query & Wright, 2003; Schulz et al., 2005; Wolff, Giovannetti, Boyd, Reider, Palmer, Scharfstein, et al., 2010). For example, a participant may identify needs related to caregiver self-care, education, skill building, and counseling. Such a caregiver would be coached throughout the intervention to set goals and pursue activities, which might include seeking out additional services and programs that address each of these multiple needs. We strongly encourage caregivers to make use of a wide range of additional services and assistance that are available in their own communities. Those services included in the REACH studies described earlier are more likely to be effective when used in various combinations to meet multiple caregiver needs. Over time, it is assumed that the caregiver would be able to initiate the tasks of assessment, goal setting, and goal attainment on his or her own, allowing the intensity and participation of the facilitator to wane over time. Thus, the overall objective of the TLC intervention is to make caregivers more aware of their need to use respite time more effectively and how to set realistic time-use goals that make respite time more satisfying. In other words, the TLC intervention can be viewed as a way to improve the coping efforts of caregivers, by helping them make the most out of what they have, while recognizing what they most want and need, and identifying how best to proceed given their unique circumstances and constraints (Riediger et al., 2006). Mastering these techniques can equip caregivers with powerful self-care tools and a newfound sense of empowerment.

PILOT TESTING THE INTERVENTION

Our pilot work includes developing, revising, and disseminating over 12,000 copies of a 16-page educational respite brochure; currently in its 5th edition (Lund, Wright, Caserta, Utz, Lindfeldt, Bright, et al., 2014). This brochure outlines (in lay terms) the rationale for valuing respite time, identifies ways to make respite more effective, and explains how goal-setting and goal attainment can lead to improved outcomes if the goals are generated from relevant self-assessment instruments. This brochure is available at the website of California State University San Bernardino (http://sociology.csusb.edu/docs/Respite.pdf) and the caregiver resources links from the website of the Administration on Aging, with free and open access to printable copies. Extensive feedback from respite users and providers has underscored potential benefits of this brochure, which provides the foundation and initial prototype of TLC intervention.

In addition, we pilot tested the TLC intervention using a convenience sample of 20 existing respite users, including four African Americans, three Latinos, and 13 Caucasians. This pilot was used to determine whether the intervention should be delivered in a weekly or bi-weekly schedule and to pilot the feasibility and usefulness of the intervention strategies. Fourteen caregivers were randomly assigned into the intervention condition and six into the non-treatment control condition. Those in the control condition completed only a pre- and post-survey to determine their satisfaction with respite time-use and their perceived burden, depression, and experiences with their caregiving experiences. Those in the control condition (“respite as usual”) were blind to the intervention group and they simply continued to use respite in the same way they had prior to the study. Of the 14 caregivers who agreed to participate in the intervention, seven were assigned to the weekly format (5 consecutive weeks of intervention) and seven were assigned to the bi-weekly format (total of three intervention sessions held every other week). The same intervention protocols related to assessment, goal setting, and goal attainment described earlier were used regardless of how often the intervention sessions were scheduled. During each intervention session, participants completed surveys measuring their satisfaction with respite time-use, level of goal attainment, and perceptions of caregiver burden (Caserta et al., 1996; Novak & Guest, 1989), and satisfaction with caregiving (Lawton, Kleban, Moss, Rovine, & Glicksman, 1989).

The first conclusion from this pilot project was that both the weekly and bi-weekly intervention formats were acceptable to the participating caregivers. Based on the feedback from the intervention facilitators we suggest that it would be most appropriate to begin with weekly sessions and then move toward bi-weekly sessions, but offering caregiver’s choices that best match their preferences. While the quantitative scales used in the pilot study were not particularly useful for statistical purposes due to the small sample size, empirical trends are suggestive of the intervention’s potential effectiveness. On the one hand, those in the control group did not change from the pre- to post-intervention assessments in their reported satisfaction with respite time or perceived satisfaction with caregiving experiences; their burden levels showed a slight increase. On the other hand, those who received the intervention showed a slight improvement in their satisfaction with respite time-use, a slight reduction in burden levels, but no notable changes in their satisfaction with caregiving. Again, none of these trends could be confirmed with statistical tests due to the small sample size. However, open-ended comments, as detailed in Table 5, provide insight into the usefulness of the intervention.

Table 5.

Qualitative Responses from Caregivers Who Participated in the Intervention Revealing the Potential Value of the Intervention

|

From these comments, it is clear that the participating caregivers recognized benefits to identifying in advance how they wanted to spend their respite time and setting specific goals helped empower them to act on their preferences. In addition to caregivers describing the perceived value of the intervention overall, the pilot data also revealed information about the specific activities caregivers most enjoyed during their respite time. The comments listed on Table 6 reveal a broad range of activities, reflecting that no single activity would fit every caregiver’s desires or needs.

Table 6.

Qualitative Responses from Caregivers Describing the Types of Activities They Most Enjoyed Doing during Respite Time

|

While these quotes do not tell the full story of the caregivers’ lives, nor do they confirm the benefits of the intervention, they are nevertheless revealing. These comments remind us that there is considerable diversity among caregiver’s circumstances and that they have sacrificed a great deal to be the primary caregivers to the family member. We cannot continue to assume that simply having respite time available will automatically result in measurable benefits to caregiver’s well-being. Each caregiver has preferences and needs but may be overwhelmed with the constant demands of caregiving such that they lose sight of the importance of self-care and how to go about acquiring it. Having a trained person (such as those described earlier) assist them in assessing and prioritizing their most immediate needs adds an element of objectivity and problem-solving that may be missing from their perspective.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The results from this pilot work serves as an important reminder that individual approaches to helping family caregivers are likely to be more effective than the commonly used “one size fits all” interventions. Accordingly, we believe that the TLC intervention model is well suited to help caregivers more effectively use their respite time by helping them pursue respite activities that best match their unique needs and desires.

When we first began to conduct research focused on caregiver’s use of respite time, we assumed that we would discover specific activities that would lead to better caregiver outcomes. We did not, however, find support for that idea. Rather, we found that what was most important to their well-being was that caregivers used their respite time engaged in activities that they described as “desired.” When there was greater inconsistency between desired and actual respite activities, caregivers experienced higher burden and dissatisfaction with caregiving (Lund et al., 2009). Also, when caregivers used their respite for activities they desired, they experienced lower burden and greater satisfaction with caregiving. When we add to this knowledge the results of our more recent pilot test of our intervention, we are more convinced of the promise that a theory-based (SOC-guided) approach will likely lead to improved well-being among caregivers who use respite services. Although we did not examine the potential of the intervention to have a positive impact on the caregiver’s self-esteem, it is possible that caregivers who become more satisfied with their respite activities could realize these benefits as well.

The crisis in caregiving that we described earlier requires immediate attention. We cannot afford to ignore the reality that there is a rapidly growing population of people in need of care, and that simultaneously we have a shrinking pool of available and willing caregivers to meet these needs. As we mentioned earlier, caregivers have needs for multiple forms of assistance that include legal, financial, emotional, social, educational, physical and mental health, and other aspects of their lives. But, having access to effective respite services is among the highest on their list of needs, in part because having time away from caregiving can allow them to focus their attention on any of these aspects of their lives. Respite can be considered as a multi-component intervention, because caregivers can select any aspect of their lives that is being jeopardized and devote some of their respite time to improving that aspect of their well-being. Respite service is an excellent complement to any other sources of help because it can provide the time needed to acquire the other services and assistance. For example, regular use of respite services can allow caregivers to obtain legal and financial help, seek educational and skill building resources, engage in social activities with friends and relatives, maintain employment outside the home, seek counseling or mental health services, pursue recreational and leisure activities, improve their self-care through exercise, nutrition, rest, relaxation, and/or simply pursue hobbies and other lifelong interests that shape their identity but have been interrupted by heavy caregiving tasks. Our intervention can be a complementary addition to, rather than a replacement for any of these other valuable services.

In short, respite services for caregivers should remain a very high priority as a strategy to help and support them, but we need to direct equal attention to improving the effectiveness of the service by focusing on time-use as a key mechanism. Otherwise, there is a risk that policy-makers could conclude that respite is not worth further investment of already limited resources and direct them elsewhere. As a result, far too many caregivers will continue to experience long-term adverse consequences as remaining options for support are depleted. The SOC model is particularly valuable as a guide to developing practical applications to help caregivers because it is well suited to various life course transitions and circumstances that require people to adjust to potential life losses. The model is intended to find ways to maximize gains and minimize further losses (Riediger et al., 2005). Also, there is a growing body of literature helping to refine the theoretical aspects of SOC along with a complementary accumulating set of research findings (Freund & Baltes, 2002; George, 2012). The SOC model lends itself very well into developing caregiver interventions because it begins with a need to assess and prioritize caregiver needs followed by carefully developing goal setting and goal attainment strategies to address these priorities. It also accounts for individual variability in caregiver circumstances and needs that makes the selection of specific outcomes more achievable. The SOC also should be equally relevant to racially and ethnically diverse caregivers because the intervention would allow them to engage in activities that could be specific to their own cultural preferences.

While the intervention we describe in this article is intended to use a one-to-one approach with a trained facilitator or coach, we hope to help develop more cost-effective options for delivering the intervention in the future. At the present time, it is essential to identify strategies that will help ensure documented and important benefits to caregivers before others begin to abandon respite as an effective and valued service. Unfortunately, respite services have not shown the positive impact on caregiver well-being that has been expected. Our approach is a relatively high resource intervention but with documented results from our work, group-based, online, and self-administered strategies could follow. Given the promising findings of our pilot studies, our future plans are to continue working to make respite more effective by testing our SOC-based intervention and theoretically based hypotheses on a much larger scale and to remain open to other creative approaches that hold promise for improving the well-being of family caregivers. Tests of this intervention model should not be limited exclusively to caregivers who use formal respite services. We are equally interested in helping all caregivers who obtain time away from caregiving to make their time and activities of maximum benefit. The TLC intervention, if proven to be effective in planned randomized trials, is designed and is to be used as an effective complementary “add-on” to already existing respite services. For example, those programs that already provide adult day center respite, extended care respite, or in-home respite services could use the respite brochure we created (Lund et al., 2014) in conjunction with applicable features of this intervention model to guide interested caregiver clients through the assessment, goal setting, and goal attainment phases to plan their respite time. This would provide the foundation for a translational research program designed and implemented to further document improved caregiver outcomes from the “add-on” intervention or service. Many caregivers want to continue their caregiving role, so it is also imperative that we find ways to allow them to do so without increased risk to their own well-being. We hope that this publication will generate more interest among researchers and service providers in focusing attention on how caregivers use their respite time and helping them to achieve improved quality of daily life.

Footnotes

Funding to support this research includes a grant from the Research Committee at the University of Utah’s College of Nursing for the pilot study we describe in this manuscript, as well as faculty support provided by the Community University Partnership and the RIMI grant from the National Institute for Minority Health & Health Disparities (P20 MD002722) at California State University, San Bernardino. This research was also supported in part by the NIH/NINR T32 training grant, Interdisciplinary Training in Cancer, Aging and End of Life Care Research, granted to principal investigators Susie Beck, PhD, RN, FAAN, and Ginny Pepper, PhD, RN, FAAN, of the College of Nursing at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT (T32NR013456).

REFERENCES

- American Psychological Association (APA) Our health at risk. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2011/health-risk.aspx.

- ARCH National Respite Network and Resource Center Respite for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia. 2007 (Fact sheet number 55). Retrieved from http://www.archrespite.org/archfs55.htm.

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM, editors. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bault MW. Americans with disabilities: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(10):727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois MS, Schulz R, Burgio L. Interventions for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A review and analysis of content, process, and outcomes. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1996;43(1):35–92. doi: 10.2190/AN6L-6QBQ-76G0-0N9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Lin IF. The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990-2010. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67(6):731–741. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs089. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale GJ, Anselmi V, Busichio K, Millis SR. Changes in ratings of caregiver burden following a community-based behavior management program for persons with traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2002;17(2):83–95. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Wright SD. Exploring the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI): Further evidence for a multidimensional view of burden. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1996;43(1):21–34. doi: 10.2190/2DKF-292P-A53W-W0A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Wright SD, Redburn DE. Caregivers to dementia patients: The utilization of community services. The Gerontologist. 1987;27:209–214. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio A, Kositsky AJ, Cohen C, Vernich L. What support do caregivers of elderly want? Results from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2001;92(5):376–379. doi: 10.1007/BF03404984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. The baby boom cohort in the United States: 2012 to 2060. 2014 Current Population Reports, P25-1141. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1141.pdf.

- Coon D. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered (LGBT) issues and family caregiving. Family Caregiver Alliance & National Center on Caregiving; San Francisco, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisdorfer C, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA, Rubert MP, Arguelles S, Mitrani VB, et al. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):521–531. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Exploring the concept of respite. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(8):1905–1915. doi: 10.1111/jan.12044. doi: 10.1111/jan.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evercare and the National Alliance for Caregiving The Evercare survey of the economic downturn and its impact on family caregiving. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/data/EVC_Caregivers_Economy_Report%20FINAL_4-28-09.pdf.

- Expert Panel on Respite Research 2013 Retrieved from http://www.lifespanrespite.memberlodge.org/ExpertPanel.

- Feinberg L, Houser A. Assessing family caregiver needs: Policy and practice considerations. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/AARP-caregiver-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update the growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. AARP Public Policy Institute. 2011 Retrieved from http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf.

- Freund AM, Baltes PB. The adaptiveness of selection, optimization, and compensation as strategies in life management: Evidence from a preference study on proverbs. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B(5):P426. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Well-being of the oldest old: An oxymoron? No! The Gerontologist. 2012;52(6):871–875. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns133. [Google Scholar]

- Gignac MA, Cott C, Badley EM. Adaptation to disability: Applying selective optimization with compensation to the behaviors of older adults with osteo-arthritis. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(3):520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Gawrilow C, Oettingen G. The power of planning: Self-control by effective goal-striving. In: Hassin RR, Ochsner KN, Trope Y, editors. Self control in society, mind, and brain. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;38:69–119. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JS, Elliott TR, Giger JN, Bartolucci AA. Social problem-solving abilities, social support, and adjustment among family caregivers of individuals with a stroke. Rehabilitation Psychology Rehabilitation Psychology. 2001;46(1):44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Habibi R, Mackenzie A. Respite: Carers’ experiences and perceptions of respite at home. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SI. Understanding patterns of service utilization among informal caregivers of community older adults. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(1):87–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp105. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann CA, Poetter U, Klumb PL. Dyadic conflict in goal-relevant activities affects well-being and psychological functioning in employed parents: Evidence from daily time-samples. Time & Society. 2013;22(3):356–370. doi: 10.1177/0961463X11413195. [Google Scholar]

- International Longevity Center [Retrieved October 30, 2013];Caregiving in America: Caregiving project for older Americans. 2006 from http://www.caregiverslibrary.org/portals/0/CGM.Caregiving%20in%20America-Final.pdf.

- Judge KS, Bass DM, Snow AL, Wilson NL, Morgan R, Looman WJ, et al. Partners in dementia care: A care coordination intervention for individuals with dementia and their family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(2):261–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq097. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosloski K, Montgomery RJV. Effects of respite on caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients: One-year evaluation of the Michigan Model Respite Programs. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1993;12:4. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Moss M, Rovine M, Glicksman A. Measuring caregiving appraisal. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1989;44(3):P61–P71. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.p61. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.P61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Utz R, Caserta MS, Wright SD. Examining what caregivers do during respite time to make respite more effective. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28(1):109–131. doi: 10.1177/0733464808323448. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Wright SD, Caserta MS, Utz BL, Lindfeldt C, Bright O, et al. Respite services: Enhancing the quality of daily life for caregivers and care receivers. (5th ed) 2014 Retrieved from http://sociolog.csusb.edu/

- Mittleman MS, Epstein C, Pierzclala A. Counseling the Alzheimer’s caregiver: Resource for healthcare professionals. American Medical Association; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. The Gerontologist. 1989;29(6):798–803. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paun O, Farran CJ, Perraud S, Loukissa DA. Successful caregiving of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Skill development over time. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2004;5(3):241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Peck MS. M. Scott Peck, M.D. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.mscottpeck.com/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Biehler L, Willison K, Hutchison B, Blythe J. Perceived support needs of family caregivers and implications for a telephone support service. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2001;33(2):43–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Query JL, Jr., Wright K. Assessing communication competence in an online study: Toward informing subsequent interventions among older adults with cancer, their lay caregivers, and peers. Health Communication. 2003;15(2):203–218. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1502_8. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1502_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot D, Feinberg L, Houser A. The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. Insight on the Issues. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.giaging.org/documents/AARP_baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-insight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: Family caregivers providing complex chronic care. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-10-2012/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care.html. [Google Scholar]

- Riediger M, Freund AM, Baltes PB. Managing life through personal goals: Intergoal facilitation and intensity of goal pursuit in younger and older adulthood. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60B(2):P84–P91. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.p84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger M, Li S-C, Lindenberger U. Selection, optimization, and compensation as developmental mechanisms of adaptive resource allocation: Review and preview. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. The handbooks of aging: Vol. 2. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6th ed. Vol. 2. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2006. pp. 289–313. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto KA, Husser E, Gigliotti C. “I don’t do things like i use to”: Multiple ways in which older women reconcile daily life with chronic health conditions; Paper presented at the Gerontological Society of American 2005 Annual Scientific Meeting; Orlando, FL. Nov, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R. Handbook on dementia caregiving: Evidence-based interventions in family caregivers. Springer; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, Gitlin LN, Wisniewski SR, Ory MG. Introduction to the special section on Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(3):357–360. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.357. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R, Eisdorfer C, Gallagher-Thompson D, Gitlin LN, et al. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): Overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directions. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):514–520. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Czaja S. Understanding the interventions process: A theoretical/conceptual framework for intervention approaches to caregiving. In: Schulz R, editor. Handbook on dementia caregiving: Evidence-based intervention for family caregivers. Springer; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Martire LM, Klinger JN. Evidence-based caregiver interventions in geriatric psychiatry. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;28(4):1007–1038. x. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.003. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seleen DR. The congruence between actual and desired use of time by older adults: A predictor of life satisfaction. The Gerontologist. 1982;22(1):95–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/22.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shope JT, Holmes SB, Sharpe PA, Goodman C, Izenson S. Services for persons with dementia and their families: A survey of information and referral agencies in Michigan. The Gerontologist. 1993;33:529–533. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawski RS, Hershey DA, Jacobs-Lawson JM. Goal clarity and financial planning activities as determinants of retirement savings contributions. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2007;64(1):13–32. doi: 10.2190/13GK-5H72-H324-16P2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Oldest baby boomers turn 60! 2006 Retrieved from http://www.sec.gov/news/press/extra/seniors/agingboomers.htm.

- Utz RL, Caserta M, Lund D. Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(4):460–471. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr110. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz RL, Lund DA, Caserta MS, Wright SD. The benefits of respite time-use: A comparison of employed and nonemployed caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2012;31(3):438–461. doi: 10.1177/0733464810389607. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver JB, Weinhardt JM, Schmidt AM. A formal, computational theory of multiple-goal pursuit: Integrating goal-choice and goal-striving processes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2010;95(6):985–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0020628. doi: 10.1037/a0020628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(2):249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF, Sebesta DS. Depression and health in family caregivers: Adaptation over time. Journal of Aging and Health. 1997;9(2):222–243. doi: 10.1177/089826439700900205. doi: 10.1177/089826439700900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Giovannetti ER, Boyd CM, Reider L, Palmer S, Scharfstein D, et al. Effects of guided care on family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(4):459–470. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp124. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Stephens MA, Townsend A, Greene R. Stress reduction for family caregivers: Effects of adult day care use. Journal of Gerontology. 1998;53B(5):S267–S277. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.s267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]