Abstract

Many causal mutations of intellectual disability have been found in genes involved in epigenetic regulations. Replication-independent deposition of the histone H3.3 variant by the HIRA complex is a prominent nucleosome replacement mechanism affecting gene transcription, especially in postmitotic neurons. However, how HIRA-mediated H3.3 deposition is regulated in these cells remains unclear. Here, we report that dBRWD3, the Drosophila ortholog of the intellectual disability gene BRWD3, regulates gene expression through H3.3, HIRA, and its associated chaperone Yemanuclein (YEM), the fly ortholog of mammalian Ubinuclein1. In dBRWD3 mutants, increased H3.3 levels disrupt gene expression, dendritic morphogenesis, and sensory organ differentiation. Inactivation of yem or H3.3 remarkably suppresses the global transcriptome changes and various developmental defects caused by dBRWD3 mutations. Our work thus establishes a previously unknown negative regulation of H3.3 and advances our understanding of BRWD3-dependent intellectual disability.

Keywords: BRWD3, HIRA, histone H3.3, intellectual disability, YEM

Introduction

Genomic DNA is wrapped around histone octamers and organized into chromatin. The dynamic chromatin structures instruct how a gene should be transcribed during developmental processes. Information associated with chromatin structure can be established and edited by at least four categories of epigenetic mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone tail modifications, nucleosome remodeling, and exchanges of histone variants. Among histone variants, the histone H3 variant H3.3 differs from the conventional histone H3.1 by only 5 residues, but has distinct deposition mechanisms and biological functions. Deposition of H3.3-containing nucleosomes is mediated by Daxx/ATRX or HIRA complex throughout the cell cycle (replication independent), whereas deposition of H3.1 into chromatin is mediated by histone chaperone CAF-1 mainly during DNA replication (replication dependent) 1. HIRA and its associated chaperone Yemanuclein (YEM), the fly ortholog of mammalian Ubinuclein1, deposit H3.3 to actively transcribed regions, nucleosome-free gaps 2, 3 and the male pronucleus at fertilization 4, 5, 6, 7. In contrast, the Daxx/ATRX complex deposits H3.3 to the telomeres 8, 9, 10. During development, deposition of H3.3 but not H3.1 establishes the epigenetic memory of an active gene state 11. Because H3.3 deposition is associated with gene transcription 12, 13 and enriched over actively transcribed regions 8, 14, it has been assumed that H3.3 could promote gene transcription. However, HIRA/YEM-mediated H3.3 deposition at the promoter regions was also shown to be required for PRC2 recruitment and bivalent gene silencing 15. Although the diverse roles of HIRA and H3.3 on gene activation and repression have been studied extensively, how HIRA/YEM-mediated deposition of H3.3 is regulated remains unknown.

Early-onset cognitive impairment, known as mental retardation or intellectual disability (ID), is defined as a reduced ability to learn new skills 16. Genetic studies suggest that ID is a disease of heterogeneous causes. For instance, in X-linked ID (XLID), which accounts for 10-12% of all forms of ID, the biological functions of the causative genes are diverse and not restricted to neurons 17. Among the XLID causative genes, CUL4B encodes the scaffold component of cullin-RING E3 ligase, CRL4B 18, 19. Like other CRL ubiquitin E3 ligases, CRL4B can ubiquitinate different substrates by incorporating a distinct substrate receptor through DDB1 (DNA damage-binding protein 1) 20. Interestingly, one of the CRL4 substrate receptors, BRWD3 (Bromodomain and WD repeat-containing protein 3), was mutated in three XLID families 21, 22. These genetic studies suggest that a BRWD3-containing CRL4 complex is critical for maintaining neural functions and structures. How the BRWD3-containing CRL4 complex functions in the nervous system is not known. Here, we report that dBRWD3, the fly homolog of XLID protein BRWD3, negatively regulates the amount of H3.3 associated with YEM and the levels of chromatin-associated H3.3. Strikingly, the diverse transcriptome changes and developmental defects found in dBRWD3 mutants were restored to normal by inactivation of the HIRA/YEM–H3.3 pathway. These findings identify dBRWD3 as a negative regulator of the HIRA/YEM–H3.3 pathway and provide a potential molecular mechanism underlying the X-linked intellectual disability.

Results and Discussion

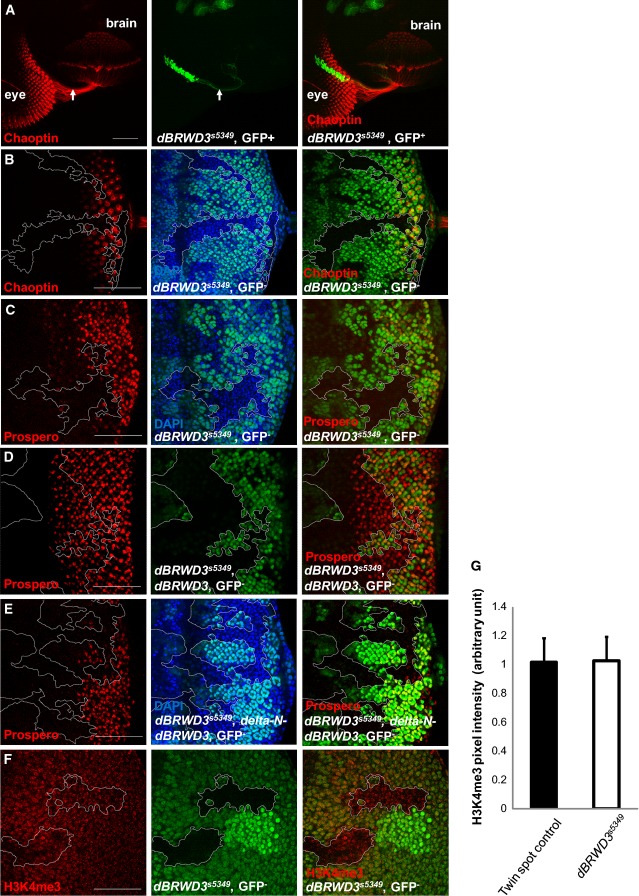

dBRWD3 regulates photoreceptor differentiation

To explore the molecular function of BRWD3 that underlies its implication in intellectual disability, we characterized dBRWD3, an essential gene encoding the only BRWD family protein in Drosophila 23. By immunofluorescence analysis, we confirmed that dBRWD3 protein is absent in the molecularly null dBRWD3 mutant, as previously reported 23 (Supplementary Fig S1A, dashed lines). In dBRWD3 mutant clones, the photoreceptors projected axons to brain normally (Fig1A, arrows, n = 52, penetrance = 100%), but did not differentiate into mature neurons expressing Chaoptin, a terminal differentiation marker (Fig1B, dashed lines, n = 56, penetrance = 92.9%). The expression of Prospero, a homeobox protein, was also markedly reduced in the mutant clones, indicating that the differentiation of R7 and cone cells is arrested (Fig1C, dashed lines, n = 23, penetrance = 100%). To determine whether dBRWD3 functions as a subunit of the CRL4 complex in these processes, we complemented dBRWD3 mutant clones with either wild-type dBRWD3 or delta-N-dBRWD3 mutant proteins that cannot bind to the DDB1 adaptor of the CLR4 complex 24. While expression of wild-type dBRWD3 restored the expression of Prospero (Fig1D, dashed lines, n = 69, penetrance of restoration = 100%) and rescued the lethality of dBRWD3 null mutants (Supplementary Table S1-1), expression of delta-N-dBRWD3 failed to do so (Fig1E, n = 27, penetrance = 92.6%, and Supplementary Table S1-1), indicating that the binding to DDB1 in the CRL4 complex is essential for dBRWD3 to regulate gene expression and animal viability. It has been shown that CRL4B mediates the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of WDR5, a core subunit of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase complexes, thereby regulating the expression of neuronal genes 25. However, H3K4me3 was not increased in dBRWD3 mutant clones (Fig1F, dashed lines, and G), suggesting that dBRWD3 regulates the development of photoreceptors and cone cells independently of WDR5.

Figure 1.

dBRWD3 is required for the differentiation of photoreceptors

- A Projection of axons from wild-type (Chaoptin positive) and dBRWD3s5349 mutant photoreceptors (GFP positive, arrows) into the medulla layer of brain optic lobe.

- B, C Expression of neuronal markers, Chaoptin (B), and Prospero (C) in wild-type (GFP positive) and dBRWD3s5349 mutant photoreceptors (GFP negative, dashed lines).

- D, E Prospero expression (red) in dBRWD3s5349 mutant clones complemented with Flag-dBRWD3 (D) and Flag-delta-N-dBRWD3, encoding a mutant dBRWD3 with a deletion of a conserved HLH-box ranging from amino acid 146 to 164 (E).

- F Expression of H3K4me3 in wild-type (GFP positive) and dBRWD3s5349 mutant photoreceptors (GFP negative, dashed lines).

- G Quantification of H3K4me3 levels in wild-type and dBRWD3s5349 mutant photoreceptors. n = 39, P = 0.54 by Student's t-test.

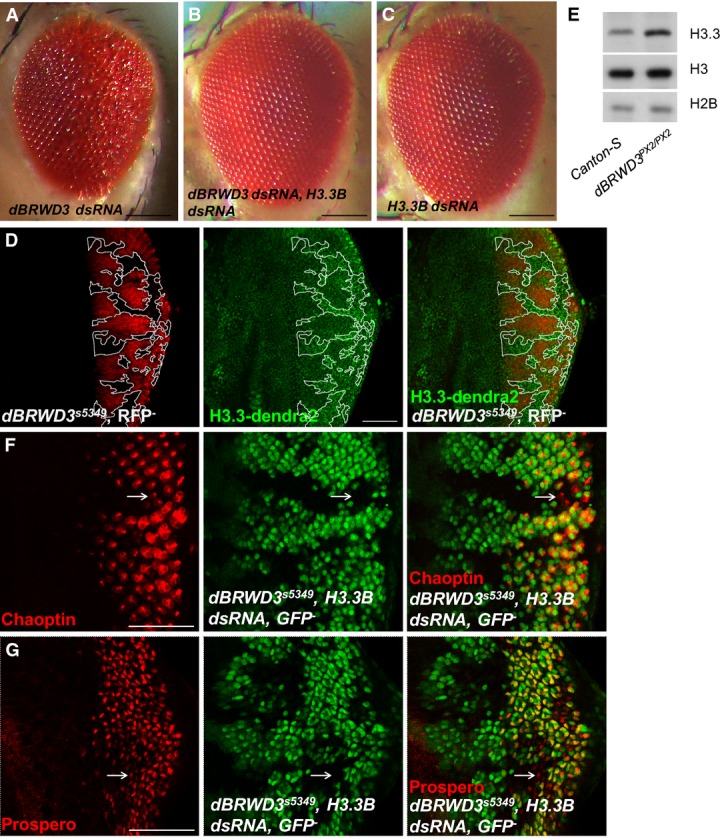

Identification of H3.3 as a suppressor of dBRWD3

To understand how dBRWD3 regulates photoreceptor differentiation, we conducted an RNAi screen to identify modifiers of the rough eye phenotype caused by knockdown of dBRWD3 in the eye imaginal disk (OK107-GAL4-driven UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, Fig2A). From the screen, we identified H3.3B, one of the two genes expressing H3.3, as a genetic suppressor. Double knockdown of H3.3B and dBRWD3 restored normal eye development (Fig2B). In contrast, H3.3B depletion alone did not cause any discernible eye abnormality (Fig2C). This result prompted us to examine whether H3.3 levels are increased in dBRWD3 mutant cells. Lacking a reliable antibody for immunofluorescence studies of endogenous H3.3, we analyzed the transgenically expressed dendra2-tagged H3.3 and found that H3.3-dendra2 levels were higher in dBRWD3 mutant photoreceptors (Fig2D, dashed lines) compared with those in wild-type twin spots. Western blot analysis confirmed an increase of both total and chromatin-associated endogenous H3.3 in dBRWD3 mutants (Fig2E; Supplementary Fig S1B). Taken together, we concluded that dBRWD3 negatively regulates the level of chromatin-associated H3.3. To examine whether the accumulated H3.3 caused abnormal gene expression, we knocked down H3.3 in dBRWD3 mutant clones. The expression of Chaoptin (Fig2F, arrows, n = 44, penetrance of derepression = 65.9%) and Prospero (Fig2G, arrows, n = 33, penetrance of derepression = 84.8%) in posterior dBRWD3 mutant clones increased when H3.3 was knocked down. Thus, the increased H3.3 also underlies the deregulation of gene expression in dBRWD3 mutant clones. Because both H3.3B and H3.3A null mutants are viable 26, 27, we were able to investigate the impact of reducing the number of H3.3 copies on the viability of dBRWD3 mutants. Strikingly, while all homozygous dBRWD3PX2/PX2 mutant larvae died at the pupal stage, more than 40% of H3.3B−/−, dBRWD3PX2/PX2 mutants emerged as adults (Supplementary Table S1-2). Therefore, these data suggested that the increased H3.3 (likely the chromatin-associated H3.3, see below) contributes to the lethality of dBRWD3 mutants. In other words, dBRWD3 is important for viability through controlling H3.3 levels. Consistently, over-expression of H3.3-GFP reduced viability in the otherwise viable transallelic, hypomorphic dBRWD306656/GS3279, but not in wild-type flies (Supplementary Table S1-3). Together, these findings indicate that dBRWD3, through its negative regulation of H3.3, is essential for gene expression and animal viability.

Figure 2.

- A-C Suppression of dBRWD3-RNAi induced rough eye phenotype by simultaneous H3.3B depletion. Images of adult eyes: OK107-GAL4-driven UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA (A), UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA (B), and UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA (C). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

- D The expression of H3.3-dendra2 under the control of ubi promoter in 3rd instar dBRWD3s5349 mutant clones generated by ey-flp (dashed lines, negatively marked by GMR promoter-driven RFP). The scale bar indicates 50 μm.

- E Western blot analysis of endogenous H3.3 and total H3. Lysates prepared from Canton S and dBRWD3PX2/PX2 3rd instar larvae. The levels of endogenous H3.3 and total H3 were detected by Western blot analysis. Histone H2B was used as a loading control.

- F, G Chaoptin (F) and Prospero (G) expression (red) in dBRWD3s5349 mutant clones (arrows) expressing GMR-GAL4-driven UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

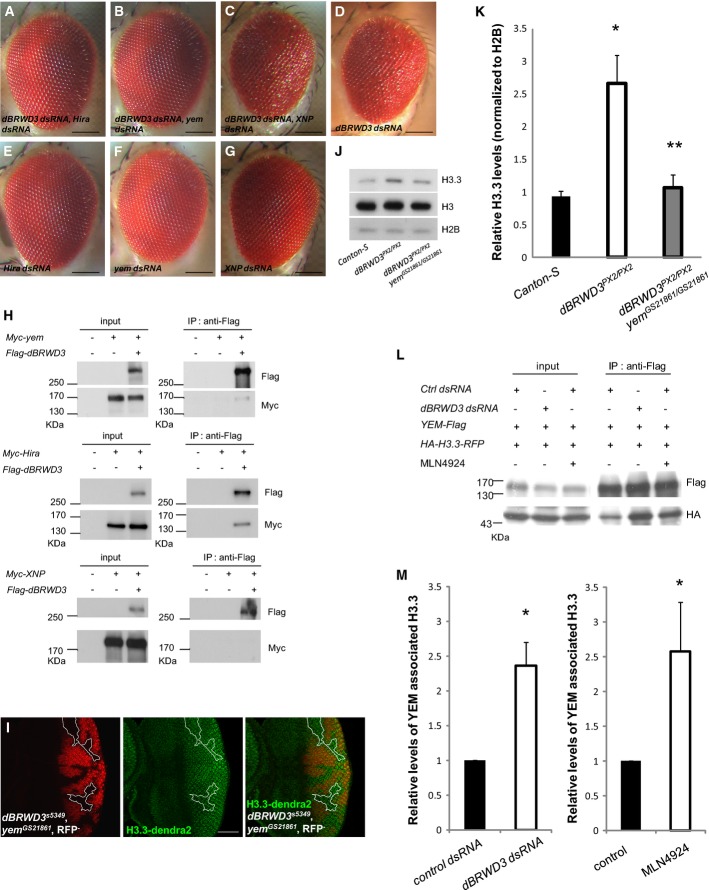

dBRWD3 depends on HIRA/YEM to regulate H3.3

Incorporation of H3.3 into chromatin is mediated by either the HIRA/YEM or Daxx/ATRX (Dlp/XNP in fly) complex 1, 9, 10. We therefore examined the functional relationship between dBRWD3 and the chaperones. Knockdown of Hira (Fig3A) or yem (Fig3B), but not XNP (Fig3C), suppressed the rough eye phenotype caused by dBRWD3 knockdown (Fig3D). As a control, knockdown of Hira (Fig3E), yem (Fig3F) or XNP (Fig3G) in a wild-type background did not result in any eye phenotype. These genetic analyses suggest that HIRA/YEM rather than Dlp/XNP complex may contribute to the increase of H3.3 levels in dBRWD3 mutant cells. Consistently, in a co-immunoprecipitation experiment, Flag-tagged dBRWD3 pulled down Myc-tagged YEM as well as Myc-tagged HIRA, but not Myc-tagged XNP (Fig3H). Domain mapping experiments revealed that HIRA directly or indirectly interacts extensively with dBRWD3 1-574a.a., 527-1214a.a., and 1049-1754a.a. fragments (Supplementary Fig S2A). In contrast, only the dBRWD3 1049-1754a.a. fragment directly or indirectly interacts with YEM (Supplementary Fig S2A). Within the dBRWD3 1049-1754a.a. fragment, bromodomain I is important since its deletion significantly reduced the interaction between dBRWD3 1049-1754a.a. and YEM (Supplementary Fig S2B).

Figure 3.

- A-G Suppression of dBRWD3-RNAi induced rough eye phenotype by simultaneous Hira or yem depletion. Images of adult eyes: OK107-GAL4-driven UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-Hira-dsRNA (A), UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-yem-dsRNA (B), UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-XNP-dsRNA (C), UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA (D), UAS-Hira-dsRNA (E), UAS-yem-dsRNA (F), and UAS-XNP-dsRNA (G). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

- H Association of dBRWD3 with YEM, HIRA, and XNP. S2 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Myc-tagged YEM (upper panel), Myc-tagged HIRA (middle panel), Myc-tagged XNP (lower panel), and Flag-tagged dBRWD3 as indicated. The expression of YEM, HIRA, XNP, and dBRWD3 were detected by Western blot analysis. dBRWD3 complex was immunopurified and analyzed by Western blot using anti-Myc antibody for the associated YEM (upper panel), HIRA (middle panel), and XNP (lower panel).

- I Suppression of dBRWD3s5349 by yemGS21861 in the expression of ubi-H3.3-dendra2. Experimental settings similar to those in Figure2D were applied to dBRWD3s5349, yemGS21861 mutants. Mutant photoreceptors are marked by the absence of RFP. The scale bar indicates 50 μm.

- J Western blot analysis of endogenous H3.3 and total H3 in Canton S, dBRWD3PX2/PX2, and dBRWD3PX2/PX2 yemGS21861/GS21861 3rd instar larvae. H2B protein levels were included as a loading control.

- K Quantification of endogenous H3.3 and total H3 in Canton S, dBRWD3PX2/PX2, and dBRWD3PX2/PX2 yemGS21861/GS21861 3rd instar larvae. Data shown were means ± SD from three independent experiments. *Indicates P < 0.01 versus Canton S and **indicates P < 0.005 versus dBRWD3PX2/PX2 by Student's t-test.

- L A representative Western analysis of YEM-associated H3.3. YEM-Flag and HA-H3.3-RFP were transiently expressed in control knockdown, dBRWD3 knockdown, and MLN4924-treated S2 cells as indicated. The YEM-associated H3.3 was immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody and analyzed by Western blot using anti-HA antibody.

- M Quantification of YEM-associated H3.3 in dBRWD3 knockdown (left panel) and MLN4924-treated (right panel) S2 cells. Data shown were means ± SD from four independent experiments. *Indicates P < 0.01 by Student's t-test.

The stabilization of H3.3 may be mediated either by its incorporation into chromatin or by blocking the rapid degradation of free H3.3. To identify which of the two processes is regulated by dBRWD3, we examined H3.3-dendra2 levels in dBRWD3, yem double mutant. The H3.3-dendra2 levels were similar to wild-type (Fig3I, n = 38, penetrance = 100%), distinct from the marked increase of H3.3-dendra2 in dBRWD3 mutant photoreceptors (Fig2D). Consistently, both the total and chromatin-associated endogenous H3.3 increased only in the dBRWD3 mutant, but not in the dBRWD3, yem double mutant (Fig3J and K, n = 3, P < 0.01, and Supplementary Fig S1B), whereas non-chromatin-associated H3.3 appeared unchanged in dBRWD3 mutant versus dBRWD3, yem double mutant (Supplementary Fig S1C). As a control, anti-H3.3 signal intensities increased linearly when the loaded chromatin fraction proteins increased (Supplementary Fig S1D). Independently, we also evaluated the ratio of chromatin-associated H3.3 to free H3.3 in salivary glands, where the exogenous, heat shock-inducible H3.3-GFP level in the control was about 70% of endogenous H3.3 (Supplementary Fig S1E) at 8 h after a 30-min heat shock. In a randomized, blind manner, we directly measured the GFP intensities that are colocalized (arrowheads in Supplementary Fig S1F and G) and non-overlapping (arrows in Supplementary Fig S1F and G) with DAPI as indexes for chromatin-associated and free H3.3, respectively (Supplementary Fig S1H). The analysis revealed an increase of chromatin-associated H3.3 relative to free H3.3 upon knockdown of dBRWD3 (Supplementary Fig S1I), suggesting an increase of H3.3 chromatin association resulted from per unit of free protein. This increase was not because of a higher H3.3-GFP mRNA expression in dBRWD3 knockdown salivary glands (Supplementary Fig S1J). Together, these data indicate that HIRA/YEM chaperone activity is required for the increased H3.3 observed in dBRWD3 mutant cells. We therefore concluded that dBRWD3 prevents an abnormal activation of HIRA/YEM, thus negatively regulating the amount of stable, chromatin-associated H3.3.

To next characterize the role of dBRWD3 on the expression of histone chaperones, we performed knockdown of dBRWD3 in the S2 cells. As a control, the nuclear dBRWD3 protein level was significantly reduced after knockdown of dBRWD3 (Supplementary Fig S3A). We next examined whether dBRWD3 depletion caused increases of HIRA, YEM, and XNP by using Western blot analyses, which revealed that loss of dBRWD3 did not change the levels of endogenous HIRA and XNP (Supplementary Fig S3B and C). In the case of YEM, although anti-YEM antibody detected overexpressed YEM well (Supplementary Fig S3D and E), it is not sensitive for endogenous YEM by either immunofluorescence or Western blot analyses (Supplementary Fig S3F and E, left panel). We therefore used an ectopic expression system—when dBRWD3 was depleted in S2 cells stably expressing YEM-Myc, YEM-Myc protein levels also did not change (Supplementary Fig S3E, right panel). To further examine HIRA, YEM, and XNP protein levels in a dBRWD3 null condition, we performed immunofluorescence studies in dBRWD3 null mutant clones. Similarly, we found that endogenous HIRA and XNP levels were not altered in dBRWD3 mutant clones (Supplementary Fig S3G and H), neither was endogenous YEM (Supplementary Fig S3I) nor the Flag-YEM (Supplementary Fig S3J) that faithfully recapitulates the expression pattern of endogenous YEM 5. Together, we concluded that dBRWD3 regulates H3.3 levels in a manner independent of degradation of H3.3 chaperones, HIRA, YEM, and XNP. We next investigated whether dBRWD3 regulates the interaction between YEM chaperone and H3.3. There was a 2.3-fold increase of the YEM-associated HA-H3.3-RFP in dBRWD3-depleted S2 cells, compared with control (Fig3L and M, left panel, n = 4). S2 cells were then treated with MLN4924 to test whether CRL4 ligase activity leads to the same outcome. As a control, MLN4924 treatment led to an increase in cullin substrate Armadillo (Supplementary Fig S3K). A similar 2.6-fold increase of HA-H3.3-RFP associated with Flag-YEM was observed (Fig3L and M, right panel, n = 4), suggesting that dBRWD3-containing CRL4 E3 ligase negatively regulates the binding of Flag-YEM to HA-H3.3-RFP. The increased H3.3 binding of YEM upon the loss of dBRWD3 is not due to an artifact of H3.3 overexpression as a similar increase was observed (Supplementary Fig S3M) in S2 cells stably expressing HA-H3.3-RFP at a much lower level than endogenous H3.3 (Supplementary Fig S3L, arrow and arrowhead). Moreover, we also observed a 2-fold increase of endogenous H4 associating with YEM in dBRWD3-depleted S2 cells (Supplementary Fig S3N).

Together, our data suggest that dBRWD3 interacts with HIRA/YEM either directly or indirectly and ubiquitinates an unidentified substrate to reduce the amount of H3.3 associated with YEM. This represents a new CRL4-mediated regulation of histone distinct from two previously reported mechanisms: ubiquitinations of H3 and H4 upon UV-induced DNA damage 28 and an ubiquitination of newly synthesized histone H3 at lysine 122 that moves H3.1 and H3.3 from ASF1 to CAF-1 and HIRA, respectively 29.

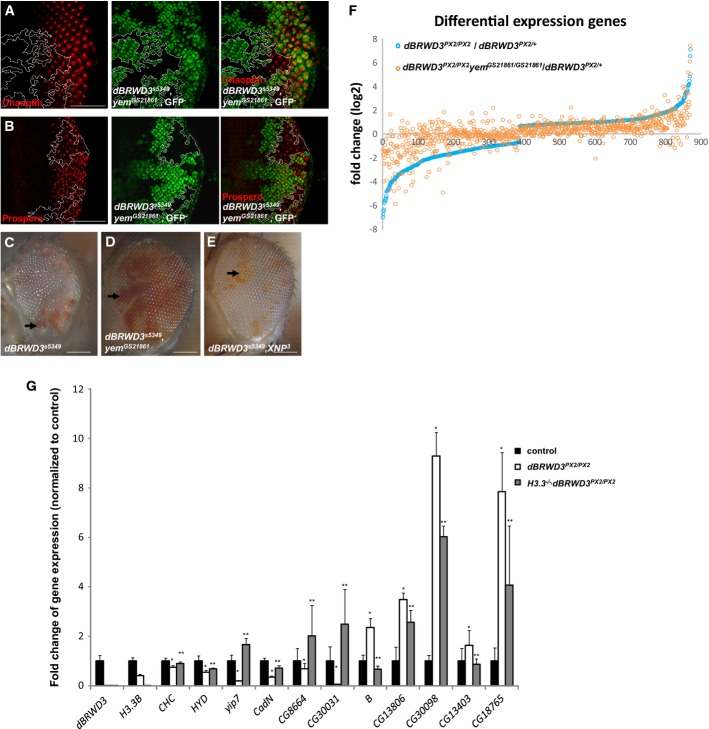

Inactivation of YEM suppresses lethality and aberrant gene expression caused by dBRWD3 mutation

To investigate how much the aberrant HIRA/YEM activity contributes to dBRWD3 mutant phenotypes, we first examined how well dBRWD3, yem double-mutant photoreceptors differentiated. The expression of neuronal differentiation markers Chaoptin (Fig4A, dashed lines) and Prospero (Fig4B, dashed lines) was restored to the wild-type level in the dBRWD3, yem double-mutant photoreceptors (n = 31 and n = 22 respectively, penetrance of restoration = 100%). In the adult stage, the number of surviving dBRWD3 mutant ommatidia, as marked in red (white+), is much smaller than wild-type twin spots marked in white (white−) (Fig4C, arrow). The number of dBRWD3, yem double-mutant ommatidia (red, Fig4D, arrow) is similar to wild-type twin clones (white, Fig4D), indicating that dBRWD3, yem double-mutant ommatidia are viable. Unlike dBRWD3, yem double mutant, the XNP, dBRWD3 double-mutant clones (carrying a deletion allele of XNP 30, Fig4E in red, arrow) are small, again suggesting dBRWD3 specifically regulates HIRA/YEM, but not Dlp/XNP. Like H3.3B, dBRWD3 double mutant, the dBRWD3, yem double mutant could survive into the adult stage, whereas dBRWD3 homozygous, yem heterozygous mutant could not (Supplementary Table S1-2), suggesting that dBRWD3 is an essential gene to prevent an abnormal activation of HIRA/YEM. To determine whether dBRWD3 also regulates HIRA/YEM in other types of neurons, we performed transcriptome analyses on larval brains of dBRWD3 heterozygous, dBRWD3 homozygous, and dBRWD3, yem double homozygous mutants. Results from next-generation sequencing revealed that the expression of 871 genes was significantly different between heterozygous control and homozygous dBRWD3 mutant brains (484 upregulated genes, 387 downregulated genes, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the 871 genes revealed a broad spectrum of biological processes, ranging from synaptic activity to housekeeping metabolism, subjective to dBRWD3 regulation (Fig4F, Supplementary Fig S4A). Among the 387 downregulated genes, the expression of 360 genes (92.8%) was increased in the dBRWD3, yem double-mutant brains compared with dBRWD3 mutant. Among the 484 upregulated genes, the expression of 412 genes (85.1%) was decreased in the double-mutant brains (Fig4F). These differentially expressed genes were evenly distributed on the X chromosome and autosomes (149 on X, 178 on 2L, 154 on 2R, 166 on 3L, and 207 on 3R), excluding the possibility of chromosome-specific regulation. These analyses indicate that dBRWD3 regulates gene expression in the brain mainly through the HIRA/YEM complex. Because the loss of H3.3 restored the expression of Chaoptin and Prospero and viability in the dBRWD3 mutant as the loss of yem did, we further investigated whether H3.3 also underlies the gene expression program regulated by dBRWD3 in brain. We examined 14 randomly chosen differentially expressed genes (seven upregulated, seven downregulated) in Canton S, dBRWD3 null and dBRWD3 null, H3.3B null double-mutant brains. Expression levels for 11 of the 14 chosen differentially expressed genes were significantly rescued in dBRWD3 null, H3.3B null double-mutant brains (Fig4G), suggesting that dBRWD3 regulates gene expression through H3.3 and HIRA/YEM. To further corroborate the notion, we examined H3.3 occupancy over 22 representative 100- to 110-bp regions, contributing 15% of total length of the seven randomly selected genomic regions. Chromatin immumoprecipitation analysis subsequently revealed a higher H3.3 occupancy on the 3′ end of CG8664 and the gene body of CG18765 (Supplementary Fig S4B), implying that dBRWD3 regulates gene expression by limiting the H3.3 level on chromatin. The chromatin landscape in Drosophila can be divided into 9 distinct functional states according to the associated histone marks and epigenetic regulators 31. To delineate the functional state of dBRWD3-associated chromatin, we examined the chromatin landscape features associated with genes that were upregulated and downregulated in dBRWD3 mutant brains (Supplementary Fig S4C). The analysis revealed that active promoter/transcription start site regions, actively transcribed exons, actively transcribed introns (enhancers), other open chromatin, and actively transcribed exons on the male X chromosome (state 1–5) were overrepresented in upregulated genes, whereas actively transcribed introns (enhancers), other open chromatin, and actively transcribed exons on the male X chromosome and heterochromatin-like regions embedded in euchromatin (state 3–5 and 8) were enriched in the downregulated genes.

Figure 4.

- A, B Expression of neuronal genes, Chaoptin (A), and Prospero (B) (red) in dBRWD3s5349, yemGS21861 mutant photoreceptors marked by the absence of GFP. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

- C-E Suppression of the cell lethality in adult dBRWD3s5349 (null) clones by yemGS21861. Adult homozygous dBRWD3s5349 (C), dBRWD3s5349, yemGS21861 (D), and XNP3, dBRWD3s5349 (E) mutant photoreceptors were generated by ey-flp and marked by white gene expression (red regions, arrows), whereas wild-type twin clones were marked by the absence of white (white regions). Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

- F Suppression of aberrant gene transcription in dBRWD3 mutant brains by yem mutation. A scatter plot of the fold changes of the differentially expressed genes in dBRWD3PX2/PX2 versus dBRWD3PX2/+ brains shown in an increasing order (blue circles). The corresponding fold changes in dBRWD3PX2/PX2, yemGS21861/GS21861 versus dBRWD3PX2/+ brains were shown as orange circles.

- G Expression of the differentially expressed genes in dBRWD3PX2/PX2 and dBRWD3 PX2/PX2, H3.3B−/− brains. The expression of B, yip7, CadN, CG8664, CG13403, CG30031, CG13806, CG30098, CHC, HYD, and CG18765 in Canton S, dBRWD3PX2/PX2 and dBRWD3 PX2/PX2, H3.3B−/− brains was analyzed by RT–PCR and presented as mean fold changes from 4 experiments relative to Canton S ± 1 SD. *Indicates P < 0.05 versus Canton S and **indicates P < 0.05 versus dBRWD3PX2/PX2 by Student's t-test.

dBRWD3 has been implicated in complex cellular processes such as migration of Elav-positive nuclei and actin organization (Supplementary Fig S5) that require coordinated expression of many genes 23. Given that most of the dysregulated genes in the dBRWD3 mutant were rescued in dBRWD3, yem double mutants, we investigated whether the additional yem mutation could restore normal nuclear migration and actin cytoskeleton. Indeed, the dBRWD3, yem double mutant exhibited normal nuclei migration and actin organization (Supplementary Fig S5), indicating that HIRA/YEM chaperone activity underlies not only gene expression but also complex cellular processes, such as nuclear migration and cytoskeleton organization.

Inactivation of H3.3 reverses the diverse defects of the dBRWD3 mutant nervous system

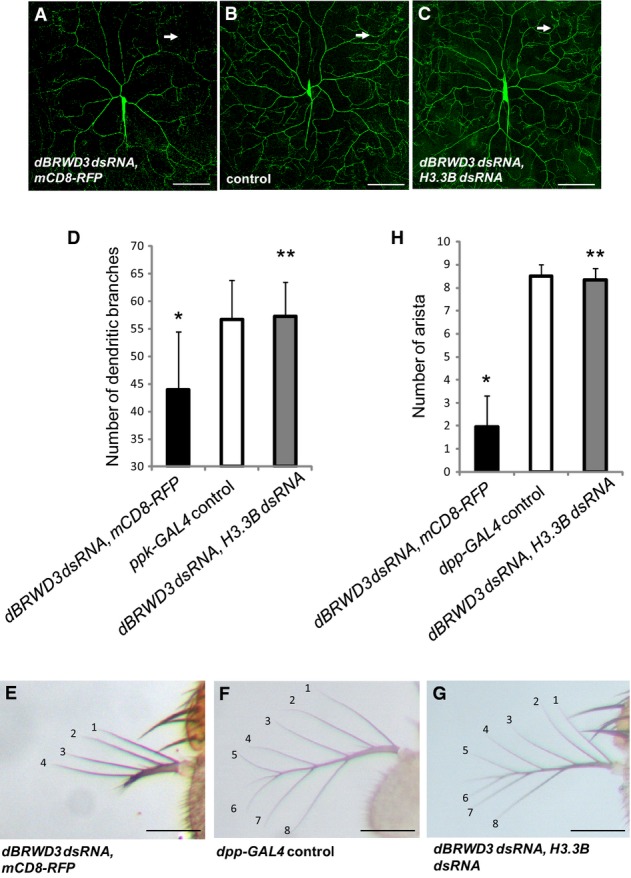

Among the 772 rescued differentially expressed genes, 349 genes (45.2%) were restored to levels comparable to control brains. Gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of neuron-related terms, including dendrite morphogenesis and antenna development (Supplementary Fig S4D). Since reduced dendritic branching has been reported in ID such as Rett's syndrome 32, we next determined whether dBRWD3 affects dendritic morphogenesis through the negative regulation of H3.3. The dBRWD3-depleted class IV dendritic arborization (da) sensory neurons had fewer dendritic branches (Fig5A) compared with the control (Fig5B), as judged by the number of dendritic branches at the periphery of the dendritic field (Fig5D). But the dendritic branches were restored in dBRWD3, H3.3B doubly depleted da neurons (Fig5C and D), supporting the notion that dBRWD3 regulates dendritic morphogenesis through the control of H3.3 levels. Similarly, the development of aristae, one of the two olfactory sensory organs in adult flies, was impaired in dBRWD3-depleted animals (Fig5E) compared with the control (Fig5F), but was restored to normal in dBRWD3, H3.3 doubly depleted animals (Fig5G and H).

Figure 5.

- A-D Dendrite morphogenesis regulated reciprocally by dBRWD3 and H3.3. Dendrite morphogenesis of class IV da neuron was highlighted by UAS-mCD8-GFP driven by ppk-GAL4. (A) Specific knockdown of dBRWD3 in class IV da neurons achieved by ppk-GAL4-driven UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-mCD8-RFP resulted in the absence of high-order dendritic branches (arrow). (B) High-order dendritic branches (arrow) increased in ppk-GAL4-driven UAS-mCD8-GFP control. (C) High-order dendritic branches (arrow) were restored in animals that simultaneously express UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA and UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA by ppk-GAL4. (D) The mean dendritic branch number at 225 μm away from the soma from 27 independent experiments was shown. The error bars indicate 1 SD. *Indicates P < 0.00001 versus GAL4 control and **indicates P < 0.00001 versus dBRWD3 knockdown by Student's t-test. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

- E-H Arista development is regulated by dBRWD3 and H3.3. (E) Knockdown of dBRWD3 in developing arista was achieved by dpp-GAL4-driven UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-mCD8-RFP. The number of branches and length were reduced in the dBRWD3-depleted arista. (F) Normal arista consists of 8–9 branches. (G) Both number of branches and length were restored in the dBRWD3, H3.3B doubly depleted arista. (H) The number of arista branches from 28 independent experiments was shown. The error bars indicate 1 SD. *indicates P < 0.00001 versus GAL4 control and **indicates P < 0.00001 versus dBRWD3 knockdown by Mann–Whitney U-test. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Conclusion

In the present study, we show that dBRWD3 regulates gene expression in the developing nervous system and viability by limiting HIRA/YEM activity to control the levels of chromatin-associated H3.3, highlighting the fact that replication-independent nucleosome assembly needs to be tightly regulated. We also show that identifying the cause underlying the complex consequences associated with dBRWD3 mutation by suppressor screening is rewarding: Inactivation of single HIRA/YEM–H3.3 pathway suppresses various complex dBRWD3 mutant phenotypes, even global gene expression and viability. The HIRA/histone H3.3 pathway might thus represent an attractive therapeutic target for ID patients with BRWD3 mutations.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

C-terminal Flag-tagged dBRWD3, dBRWD3, dBRWD3 fragments, yem, HA-yem, XNP were amplified by PCR from the cDNA clones (dBRWD3: LD40380, yem: RE33235 and XNP: LD28477, Drosophila Genetic Resource Center). delta-N-dBRWD3 lacking the region encoding amino acid 146 to 164 was generated by Thermo Scientific™ Phusion™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit. PCR products were cloned into p-ENTR-D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). pENTR-dBRWD3, pENTR-dBRWD3-Flag, pENTR-delta-N-dBRWD3, and pENTR-yem were recombined into the pUWR vector (DGRC Gateway collection) to generate RFP-tagged dBRWD3, C-terminal doubly Flag-, RFP-tagged dBRWD3, RFP-tagged delta-N-dBRWD3, and RFP-tagged yem. All pENTR-dBRWD3 fragments or deletion mutants were recombined into the pAWF vector (DGRC Gateway collection) to generate Flag-tagged dBRWD3 fragments or deletion mutants of dBRWD3 fragment (1049-1754a.a.). pENTR-yem was recombined into the pAMW vector to produce pAMW-yem (Myc-yem). pENTR-XNP was recombined into the pAMW vector to produce pAMW-XNP (Myc-XNP). pENTR-HA-yem was recombined into the pTFW vector to produce HA-yem-Flag. Hira and H3.3B CDS were PCR-amplified from cDNA, cloned into p-ENTR-D-TOPO, and recombined into the pAMW vector, the pUWR vector to produce pAMW-Hira (Myc-Hira), pUWR-HA-H3.3 (HA-H3.3-RFP), and pUWR-H3.3-dendra2 (H3.3-dendra2).

Fly strains and genetics

Flies were raised in standard conditions at 25°C. The Canton S was used as wild-type control in all experiments. The dBRWD3s5349, dBRWD3PX2, and dBRWD306656 have been described earlier 23. The dBRWD3GS3279 allele is a transposable element insertion in the 3rd intron. The yemGS21861 is a P-element insertion in the 2nd exon. Both dBRWD3GS3279 and yemGS21861 were obtained from Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Kyoto. dBRWD3s5349, yemGS21861 double mutant was generated by recombination. H3.3A and H3.3B null mutant flies were generated and described by Dr. Hödl and Dr. Basler 26. The heat shock-inducible hs-H3.3-GFP was a gift from Dr. Kami Ahmad 12. The UAS-Hira-dsRNA (NIG12153R-1) was obtained from the Fly Stocks of the National Institute of Genetics, Kyoto, Japan (NIG-FLY). The UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA (VDRC40209), UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA (VDRC12771), UAS-yem-dsRNA (VDRC26808), and UAS-XNP-dsRNA (VDRC101568) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC). UAS-dBRWD3-dsRNA, UAS-H3.3B-dsRNA was generated by recombination. OK107-GAL4 was obtained from Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Kyoto. ppk-GAL4 has been described previously 33. Other GAL4 lines and XNP3 30 were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. The transgenic flies ubi-dBRWD3-RFP, ubi-delta-N-dBRWD3-RFP, ubi-yem-RFP, ubi-HA-H3.3-RFP, and ubi-H3.3-dendra2 were generated by microinjection for germ line transformation. ubi-H3.3-dendra2 contained the CDS of H3.3B. For expression of hs-H3.3-GFP in salivary glands, larvae were heat-shocked at 37°C for 30 min and dissected after 8 h.

Further details about clonal analysis, immunoprecipitation, Western blot, cell culture, transfection, RNA interference, immunostaining, RNA sequencing, transcriptome analysis, RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Open access of data

All RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE64009.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Moses in Wellcome Trust, Dr. Ahmad in Harvard University, Dr. Hödl and Dr. Basler in University of Zurich for sharing fly stocks. We thank Dr. CC Chan, Dr. HW Pi, Dr. ST Hsieh, Dr. TP Yao, Dr. CT Chien, Dr. RH Chen, Dr. Henikoff, Dr. Workman, and Dr. Abmayr for their suggestions. This work is supported by Career Development Grant to June-Tai Wu from National Health Research Institute, NSC 101-2321-B-002-062, and MOST 101-2321-B-002-082 grants from Ministry of Science and Technology, and Translational grants from National Taiwan University and National Taiwan University Hospital. We thank Taiwan Fly Core, fly core facility in National Taiwan University, and the sixth common core lab in National Taiwan University Hospital for their technical support.

Author contributions

W-YC, K-YL, H-TS, T-HT, and Z-SS carried out, analyzed, and interpreted the experiments. W-YC also participated in the writing of the article. L-KC, M-JC, C-YC, BC-MT, and HL performed RNA sequencing and analyzed RNA-sequencing data. H-HL, BL, OA-A, and J-TW designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the article. J-TW obtained the funding and carries the overall responsibility for the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Table S2

Review Process File

References

- Tagami H, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G, Nakatani Y. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Gallet D, et al. Dynamics of histone H3 deposition in vivo reveal a nucleosome gap-filling mechanism for H3.3 to maintain chromatin integrity. Mol Cell. 2011;44:928–941. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman JI, Orsi GA, Hughes KT, Loppin B, Ahmad K. Nucleosome-depleted chromatin gaps recruit assembly factors for the H3.3 histone variant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19721–19726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206629109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loppin B, Bonnefoy E, Anselme C, Laurencon A, Karr TL, Couble P. The histone H3.3 chaperone HIRA is essential for chromatin assembly in the male pronucleus. Nature. 2005;437:1386–1390. doi: 10.1038/nature04059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi GA, et al. Drosophila Yemanuclein and HIRA cooperate for de novo assembly of H3.3-containing nucleosomes in the male pronucleus. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Koh FM, Wong P, Conti M, Ramalho-Santos M. Hira-mediated h3.3 incorporation is required for DNA replication and ribosomal RNA transcription in the mouse zygote. Dev Cell. 2014;30:268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Zhang Y. Nucleosome assembly is required for nuclear pore complex assembly in mouse zygotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:609–616. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AD, et al. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell. 2010;140:678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Noh KM, Stadler SC, Allis CD. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14075–14080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008850107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng RK, Gurdon JB. Epigenetic memory of an active gene state depends on histone H3.3 incorporation into chromatin in the absence of transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:102–109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BE, Ahmad K. Transcriptional activation triggers deposition and removal of the histone variant H3.3. Genes Dev. 2005;19:804–814. doi: 10.1101/gad.1259805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarai N, Nimura K, Tamura T, Kanno T, Patel MC, Heightman TD, Ura K, Ozato K. WHSC1 links transcription elongation to HIRA-mediated histone H3.3 deposition. EMBO J. 2013;32:2392–2406. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski LA, et al. Hira-Dependent Histone H3.3 Deposition Facilitates PRC2 Recruitment at Developmental Loci in ES Cells. Cell. 2013;155:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante L, Ropers HH. Genetics of recessive cognitive disorders. Trends Genet. 2014;30:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani S, Zapata J, Gerosa L, Moretto E, Murru L, Passafaro M. The neurobiology of X-linked intellectual disability. Neuroscientist. 2013;19:541–552. doi: 10.1177/1073858413493972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, et al. Mutation in CUL4B, which encodes a member of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complex, causes X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:561–566. doi: 10.1086/512489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey PS, et al. Mutations in CUL4B, which encodes a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, cause an X-linked mental retardation syndrome associated with aggressive outbursts, seizures, relative macrocephaly, central obesity, hypogonadism, pes cavus, and tremor. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:345–352. doi: 10.1086/511134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Zhou P. Pathogenic Role of the CRL4 Ubiquitin Ligase in Human Disease. Front Oncol. 2012;2:21. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, et al. Mutations in the BRWD3 gene cause X-linked mental retardation associated with macrocephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:367–374. doi: 10.1086/520677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotto S, et al. Clinical assessment of five patients with BRWD3 mutation at Xq21.1 gives further evidence for mild to moderate intellectual disability and macrocephaly. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Costa A, Reifegerste R, Sierra S, Moses K. The Drosophila ramshackle gene encodes a chromatin-associated protein required for cell morphology in the developing eye. Mech Dev. 2006;123:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer ES, et al. The molecular basis of CRL4DDB2/CSA ubiquitin ligase architecture, targeting, and activation. Cell. 2011;147:1024–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Xiong Y. X-linked mental retardation gene CUL4B targets ubiquitylation of H3K4 methyltransferase component WDR5 and regulates neuronal gene expression. Mol Cell. 2011;43:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodl M, Basler K. Transcription in the absence of histone H3.3. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai A, Schwartz BE, Goldstein S, Ahmad K. Transcriptional and developmental functions of the H3.3 histone variant in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1816–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhai L, Xu J, Joo HY, Jackson S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Xiong Y, Zhang Y. Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2006;22:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhang H, Wang Z, Zhou H, Zhang Z. A Cul4 E3 ubiquitin ligase regulates histone hand-off during nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2013;155:817–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AR, Cooper SE, Ragab A, Travers AA. The chromatin remodelling factor dATRX is involved in heterochromatin formation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharchenko PV, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:480–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Moser HW. Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:981–991. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueber WB, Ye B, Moore AW, Jan LY, Jan YN. Dendrites of distinct classes of Drosophila sensory neurons show different capacities for homotypic repulsion. Curr Biol. 2003;13:618–626. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Table S2

Review Process File