Summary

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) possess unique gene expression programs which enforce their identity and regulate lineage commitment. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as important regulators of gene expression and cell fate decisions, although their functions in HSCs are unclear. Here, we profiled the transcriptome of purified HSCs by deep sequencing and identified 323 unannotated lncRNAs. Comparing their expression in differentiated lineages revealed 159 lncRNAs enriched in HSCs, some of which are likely HSC-specific (LncHSCs). These lncRNA genes share epigenetic features with protein-coding genes, including regulated expression via DNA methylation, and knocking down two LncHSCs revealed distinct effects on HSC self-renewal and lineage commitment. We mapped the genomic binding sites of one of these candidates and found enrichment for key hematopoietic transcription factor binding sites, especially E2A. Together, these results demonstrate that lncRNAs play important roles in regulating HSCs, providing an additional layer to the genetic circuitry controlling HSC function.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) continuously regenerate all blood and immune cell types throughout life, and also are capable of self-renewal. Protein-coding genes specifically expressed in HSCs (HSC “fingerprint” genes (Chambers et al., 2007)) have been identified by microarray studies, and many have been shown to be functionally critical for HSC function (reviewed in (Rossi et al., 2012)). Similarly, microRNAs can regulate HSC function (Lechman et al., 2012; O’Connell et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2008).

Recent whole transcriptome sequencing has revealed a large number of putative long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). The function of some lncRNAs has been established in a limited scope of biological processes, such as cell-cycle regulation, embryonic stem cell (ESC) pluripotency, and cancer progression (Guttman et al., 2011; Hung et al., 2011; Klattenhoff et al., 2013; Prensner et al., 2011). In the hematopoietic system, only a few lncRNAs have been identified to be involved in differentiation or quiescence: Xist-deficient HSCs exhibit aberrant maturation and age-dependent loss (Yildirim et al., 2013), and maternal deletion of the H19 regulatory elements reduced HSC quiescence (Venkatraman et al., 2013). In addition, lincRNA-EPS was found to promote terminal differentiation of mature erythrocytes by inhibiting apoptosis (Hu et al., 2011), while HOTAIRM1 and EGO are involved in granulocyte differentiation (Wagner et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). Furthermore, recent genomic profiling identified thousands of lncRNAs expressed in erythroid cells. Some of them have been shown to play a role in erythroid maturation and erythro-megakaryocyte development (Alvarez-Dominguez et al., 2014; Paralkar et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, LncRNA function in HSCs still remains largely unknown. Considering that LncRNAs usually exhibit cell-type or stage-specific expression, and HSCs are rare (~0.01% of bone marrow), we reasoned that many HSC-specific lncRNAs may not yet have been identified and annotated. Notably, Cabezas-Wallscheid et al., recently identified hundreds of lncRNAs expressed in HSCs and compared their expression to that in lineage-primed progenitors (Cabezas-Wallscheid et al., 2014). However, without expression validation, comparison of expression in differentiated lineages, and functional studies, their specificity and regulatory role remains unclear. Thus, here we aimed to identify the full complement of lncRNAs expressed in HSC with extremely deep RNA sequencing, to determine LncRNAs specific to HSCs relative to representative differentiated lineages, and also to perform initial analysis of their relevance to HSC function.

Results

Identification of HSC-specific lncRNAs

In order to identify unannotated putative lncRNAs, we purified the most primitive long-term HSCs (SP-KSL-CD150+; hereafter termed HSCs) from mouse bone marrow by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). To uncover lncRNAs expressed in HSCs across different ages, we performed RNA-seq HSCs from 4 month (m04), 12 month (m12) and 24 month (m24) old mice generating 368, 311 and 293 million mapped reads for m04, m12 and m24 HSCs, respectively. In order to achieve the greatest power to detect unannotated transcripts, we also included RNA-seq data from Dnmt3a KO HSCs (Jeong et al., 2014) to reach a total of 1,389 million mapped reads for the HSC transcriptome. Although Dnmt3a KO HSCs inefficiently differentiate, they retain many features of normal self-renewing HSCs adding power to novel gene discovery. In addition, we performed RNA-seq on sorted bone marrow B cells (B220+) and Granulocytes (Gr1+) for comparison. We then performed a stringent series of filtering steps to identify lncRNAs in different ages of WT HSCs, including a minimum length of 200 bases and multiple exons (Figure 1A).

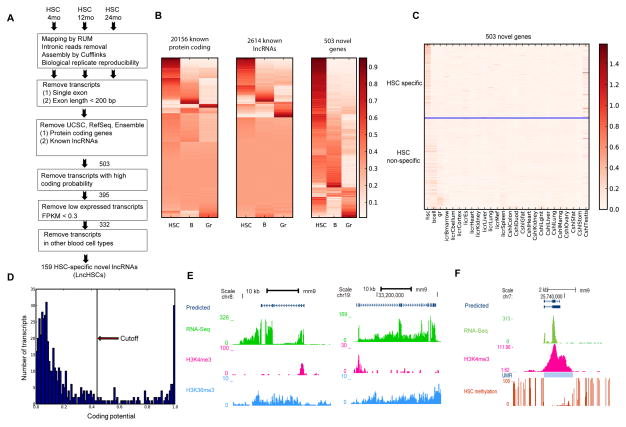

Figure 1. Identification of HSC-specific LncRNAs.

(A) Flowchart for identification of LncHSCs. Filters indicate exclusion criteria.

(B) Heatmap to compare gene expression between HSCs, B cells and Granulocytes, including protein-coding genes, previously annotated lncRNAs and unannotated transcripts.

(C) Expression of the transcripts identified in HSCs, B cells, Granulocytes and 20 other tissues, including Cerebellum, Cortex, ESC, Heart, Kidney, Lung, Embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), Spleen, Colon, Duodenum, Mammary gland, Ovary, SubcFatPad (Subcutaneous Adipose tissue, Sfat), GenitalFatPad (Gfat), Stomach, Testis and Thymus (GSE36025 and GSE36026).

(D) Coding potential prediction by CAPT for 503 unannotated transcripts identified in HSC.

(E) UCSC browser track showing two LncHSCs, with expression (green), H3K4me3 signal (pink) and H3K36me3 (blue).

(F) UCSC browser track showing one LncHSC is located in the UMR, with expression (green), H3K4me3 signal (pink) and DNA methylation (red), and UMR (blue bar).

We first verified the high quality of our data by confirming lineage-specific expression of known protein-coding “fingerprint” genes (Chambers et al., 2007), such as Myct1, Ebf1 and Cldn1 with HSC–, B cell–, and granulocyte–specific expression, respectively (Figure S1A). Next, we identified 2,614 transcripts previously annotated as non-coding RNAs by UCSC Known Gene, RefSeq or Ensemble databases. Comparing their expressions in these three cell types revealed 154, 57 and 81 lncRNAs were enriched to HSCs, B-cells and Granulocytes (Table S1), such as AK018427, AK156636 and AK089406 (Figure S1B).

With known genes filtered out, we focused on the remaining un-annotated and multiple-spliced transcripts, which resulted in 503 unannotated genes in HSC. Comparison of the expression of these transcripts in HSCs, B-cells and Granulocytes revealed that almost one third were HSC specific (Figure 1B). Comparing their expression in 20 additional tissues (RNA-seq data from Encode) showed generally low expression across most tissues except a few expressed in testis (Figure 1C), suggesting they are highly hematopoietically enriched (HE) (Table S1). Prediction of their coding probability using CPAT software (Wang et al., 2013) revealed 395 with low coding probability (< 0.44), representing likely non-coding RNAs (Figure 1D). We further filtered out minimally expressed transcripts in WT HSCs, if their FPKM < 0.3 at all three different ages, which gave rise to 332 genes. Comparison of their expressions in B cells and Granulocytes resulted in 159 high-confidence lncRNAs that are HSC-enriched (Table S1). A similar assembly of B cell and Granulocyte RNA-seq reads identified 124 B cell– (LncB) and 107 granulocyte–enriched (LncGr) previously unannotated transcripts (Table S1). Notably, most of the B cell-specific transcripts identified this way correspond to antibody variable regions.

We next examined the features of the set of HSC-enriched lncRNAs (named LncHSCs). The LncHSCs generally have fewer exons, lower expression, but similar transcript lengths and conservation (PhastCon) scores compared to protein coding genes (Figure S1C–F), in line with previous reports (Derrien et al., 2012). As retrovirus-related transposon elements (TEs) have been shown to be enriched in ESC lncRNAs (Kelley and Rinn, 2012), we considered whether this was also applicable to LncHSCs. Consistent with a previous report (Kapusta et al., 2013), we found that TEs cover about 40% of genomic sequence, 15% of known lncRNAs, but 5% for protein coding genes. For LncHSCs, TEs (particularly LTR-associated; Figure S1G) contribute to about 35% of their genomic sequences. These results suggest that LncHSCs here are distinct from protein coding genes and likely to act as lncRNAs.

We further examined the chromatin state of the LncHSCs. ChIP-seq data for two activation-associated histone marks H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 in purified WT HSCs were obtained from previous studies (Jeong et al., 2014). For LncHSCs, H3K4me3 was typically located at their predicted transcriptional start site (TSS) and H3K36me3 along their gene bodies (Figure 1E). For DNA methylation, whole genome DNA methylation analysis in HSC showed that 62% of lncHSCs are marked by undermethylated regions (UMRs) in their promoter regions, some are even located in a methylation canyon (UMR>3.5 kb) (Jeong et al., 2014). One example is located in a canyon with a broad H3K4me3 peak (Figure 1F). Another example whose transcription originates from the promoter of an active protein coding gene (Figure S1H), is classified to previously described divergently transcribed lncRNAs (Sigova et al., 2013).

LncHSCs showed altered expression with HSC functional decline

To gain insights into the function of LncHSCs in HSC self-renewal and differentiation, we compared their expression between different HSC ages, and between WT and Dnmt3a KO HSCs, because our previous studies showed that aged HSCs exhibited a repopulation defect and myeloid-biased differentiation, and Dnmt3a−/− HSCs exhibit defective differentiation and enhanced self-renewal (Challen et al., 2012). There are a small subset of LncHSCs (29 out of 159) whose expression changes between 4mo and 24mo HSCs (FDR<1E-04). However, almost 58% (92 out of 159) of LncHSCs showed significant expression changes (FDR<1E-04) between age-matched m12 WT HSC and Dnmt3a KO HSCs (Figure 2A). To examine the basis for these differences at the epigenetic level, whole genome bisulfate sequencing of WT and Dnmt3a KO HSCs (Jeong et al., 2014) was analyzed. Interestingly, a majority of LncHSCs show strong loss of DNA methylation at their TSS regions after Dnmt3a KO, suggesting a role for Dnmt3a in their regulation. For example, LncHSC-1 to 6, all show decreased methylation at their TSS regions, however, decreased methylation was not always correlated with expression changes (Figure S2A): LncHSC-1 and –2 exhibit decreased expression; LncHSC-3 and –4 show up-regulation and are accompanied by increased H3K4me3 (Figure 2B); and LncHSC-5 and 6 do not show significant expression changes (Figure S2B). This relatively poor correlation between DNA methylation changes and gene expression alteration resembles the observations from protein-coding genes (Challen et al., 2012).

Figure 2. Transcriptional regulation of LncHSCs.

(A) Heatmap depicting expression of 159 LncHSCs: 4mo HSC vs 12mo HSC and 24mo HSC (Left panel); WT vs Dnmt3a KO HSC (Right panel).

(B) UCSC browser track showing expression (green), H3K4me3 signal (pink) and DNA methylation (red) for LncHSC-3 and LncHSC-4 in WT and Dnmt3a KO (3a KO) HSCs. Grey bars show differential DNA methylation between WT and 3a KO HSCs.

(C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of selected LncHSCs. 50,000 KSL cells (c-Kit+Sca-1+Lin), CD4 T cells (CD4+), CD8 T cells (CD8+), B cells (B220+), Macrophages (Mac1+), Granulocytes (Gr1+) and Red blood cells (TER119+) were sorted for RT-PCR. The expression levels were plotted relative to that in KSL cells (set as 100, n=3, Mean ± SD).

(D) UCSC browser track showing DNA methylation (red), expression (green), H3K4me3 (pink), H3K27me3 (orange), H3K27ac (dark green) and H3K4me1 (blue).

(E) Representative images of LncHSC-1 expression in HSCs analyzed by RNA-FISH. Green is 18srRNA signal and Red is LncHSC-1 signal.

(F) Representative images of LncHSC-2 and LncGr-1 expression in HSC and Granulocytes analyzed by RNA-FISH. Green is LncHSC-2 signal and red is LncGr-1 signal.

We also examined the promoters (TSS ± 5 kb) of LncHSCs for critical HSC-associated transcription factor (TF) binding. Using published ChIP-seq data for 10 key HSC TFs, including Erg, Fli1, Lmo2, Meis1, Gata2, Runx1, PU.1, Scl, Lyl1and Gata2, across a variety of blood lineages (>10) (Hannah et al., 2011), we found that 51% of LncHSCs contain at least one or more TF binding sites on their promoters (e.g., LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2, Figure S2C). Among these 10 TFs, Erg, Flil1 and Pu.1 are the top three factors, exhibiting binding sites near 38%, 29% and 25% of LncHSCs, respectively. This percentage is comparable to protein-coding genes, but much higher than the genome random control, suggesting that the expression of LncHSCs may be precisely regulated by hematopoietic TFs (Figure S2D).

Next, we selected LncHSC-1 through –6 for expression validation by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). Among them, two overlapped with unannotated EST tags: LncHSC-1 (AK039852), LncHSC-2 (DT926623). Notably, LncHSC-2 is represented as an EST on Affymetrix microarrays (MOE430 V2.0) and has been previously identified as an HSC fingerprint gene (Chambers et al., 2007) (Figure S2E). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that LncHSC-1-6 are highly expressed in stem and progenitor cell populations (KSL), but not, or at very low levels, in six other terminally differentiated blood lineages (CD4, CD8, B220, Gr1, Mac1 and Ter119) (Figure 2C). For LncHSC-4, we detected higher expression in erythroid cells (Ter119) than other blood lineages. Indeed, LncHSC-4 (aka Lincred1 (Tallack et al., 2012) has been shown to be regulated by Klf1, Gata1 and Tal1, and possibly involved in erythroid differentiation.

To gain insights into how LncHSCs control HSC function, we focused on LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2, which exhibit several features of interest. These two transcripts are highly expressed in WT HSC (FPKM>3), but suppressed in Dnmt3a KO HSCs (Figure S2B) and their promoter regions are bound by multiple TFs in hematopoietic progenitor cells (Figure S2C). Further expression analysis in HSC and different progenitors revealed that LncHSC-1 is more HSC specific, and LncHSC-2 is expressed in HSC and also different progenitors, but not terminally differentiated cells (Figure S2F). Moreover, we found that LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2 are transcribed from enhancer regions, marked by H3K27ac or H3K4me1, but not H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (Figure 2D). LncHSC-1 is located between two functionally important coding genes, Zfp36l2 and Thada. Genomic translocation was reported within Thada and distal to the Zfp36l2 locus in various myeloid malignancies (Trubia et al., 2006). In addition, heterozygous mutations of Zfp36l2 were detected in leukemias (Iwanaga et al., 2011). Zfp36l2 homozygous knockout mice die from HSC failure within 2 weeks of birth (Stumpo et al., 2009) and recently it was reported that Zfp36l2 is required for self-renewal of erythroid progenitors (Zhang et al., 2013). The human synteny block including LncHSC-1 is also located between THADA and ZFP36L2 on Chromosome 2. RNA-seq data from bone marrow of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) patients (Ley et al., 2010) indicated there are several un-annotated transcripts expressed in this region. However, based on sequence homology, we could not identify specific orthologs to LncHSC-1, consistent with generally poor conservation for lncRNAs across species (Ulitsky et al., 2011). In mouse HSCs there are four LncHSCs (LncHSC–1, –3, –82 and –13) between Thada and Zfp36l2 genes, all four of which showed expression changes after Dnmt3a KO, with LncHSC-1 and –13 down-regulated, and LncHSC-3 and –82 up-regulated (Figure S3A). To examine how the transcripts in this region were impacted by human DNMT3A mutations, we reconstructed and selected from TCGA AML patient data one abundantly expressed transcript at this region (corresponding to the EST tag AF150238) (Figure S3B), and found that patients with DNMT3A mutation showed increased expression (P-value=0.01) (Figure S3C). These data suggest similar regulation of putative lncRNAs by DNA methylation in this syntenic region, despite lack of clear sequence homology. Whereas LncHSC-2 is close to a protein coding gene Pkn2, sequence comparison by BLASTN revealed it is highly homologous (87.6%) to a 3 kb region in its human synteny block, which is also close to PKN2 gene. However, we did not detect expressed transcripts at this region in TCGA patients.

LncRNA function is also dependent on subcellular localization. Enhancer-associated lncRNAs are more enriched in the nucleus, whereas lncRNAs involved in other functions such as post-transcriptional and translational processes tend to be more cytoplasmic. We thus performed RNA FISH to determine the localization of LncHSCs. LncHSC-1 is mainly located in the HSC nucleus compared to the control 18s rRNA (Figure 2E). In parallel, LncHSC-2 is also located in the HSC nucleus, suggesting that LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2 are likely functional non-coding RNAs. To confirm their specificity, we also examined one Granulocyte-enriched LncRNA (LncGr-1), which was found to be exclusively expressed in granulocytes, but not in HSCs (Figure 2F).

LncHSCs control HSC in vitro and in vivo differentiation

To characterize the functions of LncHSC-1/2, we generated retrovirally expressed constructs to knockdown (KD) their expression (Figure 3A). In stem and progenitor cells (Sca-1+), the KD constructs led to 50–70% reduction of their expression by RT-PCR (Figure 3B). To examine their effects on HSC self-renewal and differentiation, retrovirally-transduced KSL-GFP+ cells were sorted after 2 days of in vitro culture and plated in methylcellulose for CFU assays. Knockdown of those transcripts had no effect on the colony number or the lineage specificity after the first plating (Figure S3D). However, after the second plating, KD of LncHSC-1 significantly increased the colony numbers compared to the control, suggesting that progenitors with reduced LncHSC-1 in the first plating had not undergone terminal differentiation (Figure 3C). Indeed, KD of LncHSC-1 led to an increase in cells expressing the HSC/progenitor marker c-Kit (Figure S3D), and cells from second-plating colonies had a more homogeneous morphology (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. LncHSCs regulate HSC differentiation in vitro.

(A) Flow chart depicts knockdown of LncHSC for in vitro and in vivo functional studies.

(B) Q-RT-PCR to show LncHSCs knockdown. Sca-1+ cells were transduced with knockdown constructs, cultured in vitro for two days, then 20,000 GFP+ cells were sorted for RT-PCR (n=3, Mean ± SD).

(C) Methylcellulose CFU assay using 200 KSL-GFP+ cells (transduced by LncHSC-1 KD-1 and LncHSC-2 KD-1). Sorted cells were put into a well of 6-well plate containing Methocult3434 and average colony number counted after 14 days. For the second plating, 2,000 live cells from the colonies obtained in the first plating were plated as before and cultured for 14 days. ** P< 0.01. (n=3, Mean ± SD). Representative of 3 experiments.

(D) Morphology of cells from the colonies at the second plating by cytospin.

See also Figure S3.

Next we performed transplantation to examine the function of LncHSC1/2 in vivo. As we observed that KD of LncHSC-1 increased the myeloid colony number in vitro, we also generated retroviral constructs to over-express LncHSC-1 in stem/progenitor cells. However, after transplantation for 16 weeks, even though the LncHSC-1 transcript level increased by almost 500-fold in the GFP+ (Lin− c-kit+ Sca-1+) KSL cell population, there was no difference in lineage differentiation (Figure S3E–F). Meanwhile, we transplanted the stem/progenitor cells transduced with the LncHSC-1/2 KD constructs. 16 weeks after transplantation, the percentages of donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) in the peripheral blood were similar between the groups. However, although the initial transduction efficiency (Figure S4A) and donor engraftment efficiency (Figure S4B) are similar, the percentage of the GFP+ population varied significantly between different groups (Figure 4A), possibly due to the effects of LncHSC on HSC self-renewal. To determine their impact in lineage differentiation, we compared percentage of different lineages within GFP+ population. We found that KD of LncHSC-1 significantly increased myeloid differentiation at the expense of B cells compared to control KD, aligned with the in vitro findings. In contrast, KD of LncHSC-2 significantly increased T cell lineage and decreased B cell output. As a control, the CD45.2+GFP− population showed similar lineage distributions between different groups (Figure 4B). To confirm the KD efficiency in vivo, we isolated bone marrow (BM) GFP+KSL cells at 20 weeks after transplantation for RT-PCR and confirmed that LncHSCs were knocked down (Figure S4C).

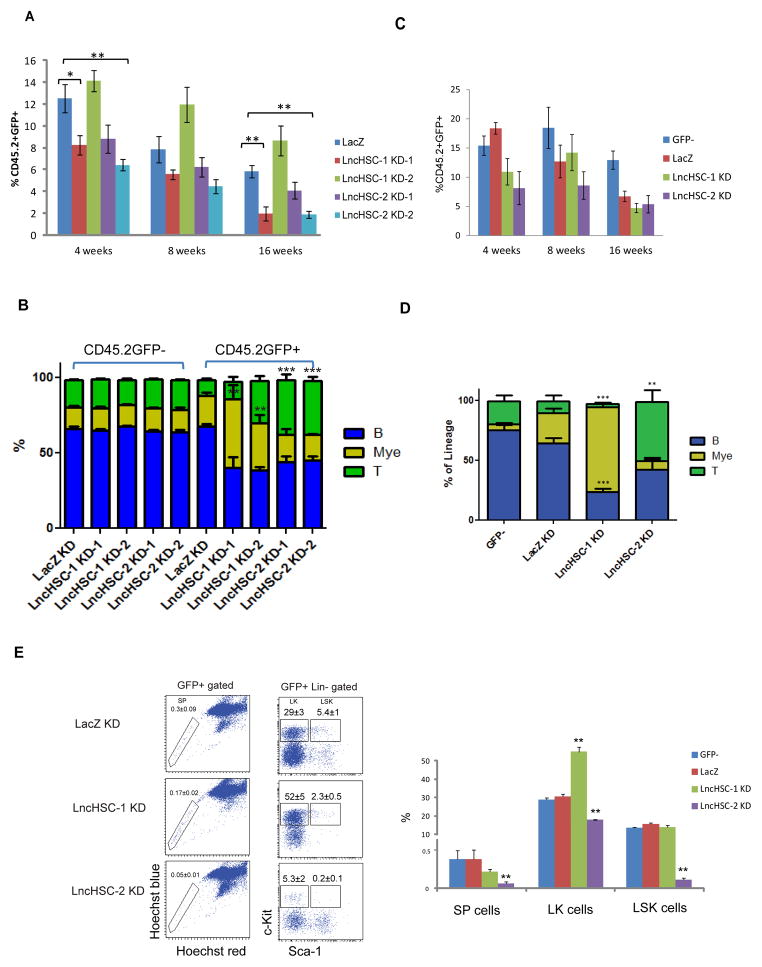

Figure 4. LncHSCs control HSC function in vivo.

(A) Contribution of retrovirally-transduced donor HSCs (CD45.2+GFP+) to recipient mouse PB after primary transplantation. *** P <0.001, ** P< 0.01, * P<0.05. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. (n=10 for Control KD, n=5–8 for LncHSCs KD).

(B) Analysis of HSC differentiation in peripheral blood at 16 weeks post-primary transplant. The % of the indicated lineages within CD45.2+GFP− or CD45.2+GFP+ cell compartment are shown. Myeloid cells (Mye) were defined as Gr1+ and Mac1+, B-cells (B) are B220+, T-cells (T) are CD4+ and CD8+.. *** P <0.001, ** P< 0.01, * P<0.05. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. (n=10 for Control KD, n=5–8 for LncHSCs KD).

(C) Contribution of donor HSCs (CD45.2+GFP− or CD45.2+GFP+) to recipient mouse PB after secondary transplantation. Mean ± SEM. (n=5–6). For secondary transplantation, 500 CD45.2+GFP+ KSL cells from primary recipients were re-sorted 20 weeks after transplantation and mixed with 250,000 CD45.1 WBM cells, and injected into new lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients.

(D) Analysis of peripheral blood cells at 16 weeks post-secondary transplant. The % of the indicated lineages within CD45.2+GFP− and CD45.2+GFP+ cell compartment are shown. Myeloid cells (Mye) were defined as Gr1+ and Mac1+, B-cells (B) are B220+, T-cells (T) are CD4+ and CD8+.. *** P <0.001, ** P< 0.01, * P<0.05. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. (n=5–6).

(E) Bone marrow FACS analysis showing frequencies of side population, LK and LSK cells 16 weeks after secondary transplantation in mice. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01. (n=3–6)

We further performed lineage, progenitor and HSC analysis in the bone marrow after 20 weeks. Notably, the bone marrow GFP+ population in LncHSC-1 KD-1 and LncHSC-2 KD-2 groups was too low for detailed HSC and progenitor analysis, so we focused on LncHSC-1 KD-2 (shRNA#2) and LncHSC-2 KD-1 (shRNA#1) groups. We found there were no significant differences for GMP, CMP and MEP population or LT-HSC, ST-HSC and MPP population after KD (Figure S4D). However, we observed that KD of LncHSC-1 led to increased myeloid cells and LK cells (myeloid progenitors), KD of LncHSC-2 led to more T cells, consistent with the peripheral analysis (Figure S4E).

To examine HSC self-renewal activity, 500 BM GFP+KSL cells from primary recipients of LncHSC-1 (KD-2) and LncHSC-2 (KD-1) were sorted and transplanted into secondary recipients. PB analysis showed GFP+ level were comparable between different groups (Figure 4C), KD of LncHSC-1 increased myeloid differentiation and KD of LncHSC-2 increased T cell differentiation, consistent with primary transplantation results (Figure 4D). For the bone marrow analysis at 16 weeks after secondary transplantation, interestingly the percent of side population (SP) and KSL cells were decreased for LncHSC–2 KD, suggesting that LncHSC-2 is involved in HSC long-term self-renewal (Figure 4E).

While bone marrow of primary recipients of LncHSC-2 KD-2-transduced cells had too few GFP+ cells for detailed analysis, we were able to isolate enough KSL GFP+ cells from a pool of these mice and to perform secondary transplantation, in order to verify the effect on self-renewal. Again, we observed that the percent of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood was very low at 4 weeks, and almost undetectable at 16 weeks (Figure S4F); this precluded us from lineage analysis with this KD construct. In the bone marrow at 16 weeks, we observed dramatically decreased total GFP+ cells for both LncHSC-2 KD constructs, but not LncHSC-1 KD (Figure S4G). These results suggest that both shRNAs for LncHSC-2 affected HSC self-renewal, but with different efficiency.

The mechanisms through which lncRNAs work are largely obscure and are likely to vary. It has been shown that LncRNAs can modulate gene expression through RNA-protein, RNA-RNA or RNA-DNA interactions (Guttman and Rinn, 2012). To determine the immediate impact on gene expressions after LncHSC KD, stem and progenitor cells were transduced with retrovirus. After in vitro culture for 2 days, GFP+ KSL cells were purified and subjected to RNA-seq. As expected, the results revealed the targeted LncHSCs were specifically reduced. However, we only identified 70 and 84 significantly changed genes after KD of LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2, respectively (Table S2). Moreover, we did not see any expression changes of neighboring genes after KD of either LncHSC-1 or LncHSC-2, indicating that LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2 are possibly trans-acting lncRNAs.

ChIRP-seq reveals LncHSC-2 occupancy sites genome wide

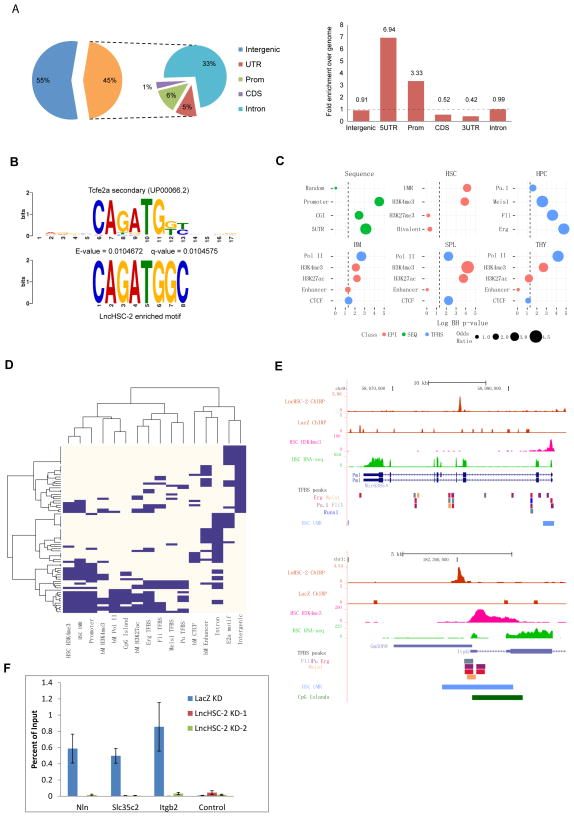

To better understand the functions of LncHSCs, we sought to determine their binding sites by Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification (ChIRP)-seq (Chu et al., 2011; Engreitz et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2011). Given the technical challenges due to the limited number of primary HSCs, we utilized HPC5 cells, a mouse bone marrow-derived multipotent progenitor line (Pinto do et al., 2002) which expresses LncHSC-2 at levels comparable to primary HSCs. We thus performed ChIRP-seq to identify LncHSC-2 binding sites using HPC5 cells. After pull-down, RT-PCR showed that more than 90% of LncHSC-2 RNA was pulled-down. For the negative control, less than 1% of GAPDH RNA was pulled-down (Figure S5A). From CHIRP-seq, we identified 264 LncHSC-2 binding sites concordant in three of four biological replicates and absent in a LacZ negative control (for peak coordinates, see Table S3). Similar to transcription factors, LncHSC-2 binding sites were focal (median size = 284 bp) and most did not spread beyond 600 bp. The distribution of binding sites showed ~11% were localized to promoter/5′ UTR elements (Figure 5A left), representing a 3–7-fold enrichment over genome background (Figure 5A right). The remaining peaks occurred primarily in intronic and intergenic regions.

Figure 5. ChIRP-seq reveals LncHSC-2 binding sites in genome.

(A) LncHSC-2 binding sites are enriched in promoter-proximal regions. Left, pie chart shows the distribution of LncHSC-2 binding sites across the indicated intergenic or intragenic regions. Right, enrichment of LncHSC-2 sites (versus genomic background) among transcript features.

(B) Enriched sequence motif associated with lncHSC-2 binding sites (bottom) strongly resembling the mouse Tcfe2a secondary motif (top).

(C) Co-enrichment analysis of lncHSC-2 binding sites with sequence features, ChIP-seq profiles of hematopoietic transcriptional regulators and epigenetic marks in HSC, multipotent progenitors (HPC-7 cells), bone marrow, thymus, and spleen. Enrichment for LncHSC-2 binding compared to LacZ negative control was assessed by Fisher’s exact test with multiple testing correction. Colors subdivide the results into three classes: epigenetic mark (red), sequence feature (green), and TF binding site (blue). Dot sizes are proportionate to the Odds Ratio. The x-axis values represent the – log Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-value.

(D) Hierarchical clustering of genomic regions bound by lncHSC-2 and published hematopoietic lineage TF or epigenetic marks. The major partition of columns separates LncHSC–2 occupancy into two main branches, with unmethylated promoter proximal regions associated with transcriptional activation marks (H3K4me3/H3K27ac/PolII) and Erg/Fli/Meis1/Pu.1 TFs to the left and promoter distal intronic or intergenic regions associated with bone marrow tissue enhancer or insulator elements (CTCF), E2A sequence motifs to the right. Each line corresponds to a LncHSC-2 peak where blue/white coloring indicates the presence/absence of the additional given factors.

(E) LncHSC-2 occupancy at the genes Pml (top) and Itpkb (bottom). LncHSC-2 and LacZ control ChIRP-seq signal density tracks generated by MACS2 representing the fragment pileup signal per million reads. Additional overlaid tracks are HSC H3K4me3, RNA-seq, undermethylated regions (Jeong et al., 2014) and hematopoietic lineage TF binding sites (Wilson et al., 2010).

(F) ChIP-qPCR to show E2A binding to three LncHSC-2 binding peaks after LncHSC-2 KD in primary Sca-1+ cells. Y-axis represents the % of immunoprecipitated DNA compared to input. Mean ± SEM values are shown (n=4).

See also Figure S5 and Table S3–S6.

Next, we asked whether LncHSC-2 accesses the genome through specific DNA sequences. Motif analysis of LncHSC-2 binding sites identified four core motifs (Table S4), suggesting that specific DNA motifs may be involved in LncHSC-2 occupancy. To further characterize the motifs, we quantified their similarity to known DNA sequence motifs. This revealed a significantly enriched bHLH motif corresponding to a transcription factor E2A isoform encoded by Tcf3 (Figure 5B, and Table S4). E2A proteins act to promote the developmental progression of the entire spectrum of early hematopoietic progenitors, including LT-HSC, MPP, and CLP (Semerad et al., 2009). To gain insight into potential LncHSC-2-mediated chromatin states, we tested the over-representation of its occupied sites (relative to LacZ control) among the ChIP-seq profiles of hematopoietic transcriptional regulators and epigenetic marks in LT-HSC, multipotent progenitors (HPC-7 cells), as well as tissues (bone marrow, thymus, spleen). LncHSC-2 sites were characterized by significant enrichment of undermethylated CpG regions (UMRs), active histone marks H3K4me3/H3K27ac, and TFs Erg/Fli1/Meis1/Pu.1 (Figure 5C and Table S5). Remarkably, GREAT analysis of mouse genotype-phenotype associations showed gene and promoter proximal binding sites were significantly enriched almost exclusively for hematopoietic and immune system phenotypes (14 of 16 terms with binomial test q < 0.05), including abnormal lymphopoiesis (Table S5).

Having identified potential associations between LncHSC-2 and individual transcriptional regulators and epigenetic marks, we next analyzed occupancy patterns of regions bound by LncHSC-2 and enriched factors by hierarchical clustering. This analysis separated LncHSC-2 bound sites into two major clusters: (1) undermethylated promoter proximal regions associated with activating chromatin marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac), hematopoietic TFs and (2) promoter distal intergenic/intronic regions with associated with insulator CTCF, enhancers, or E2A binding motifs (Figure 5D). One LncHSC-2 occupied site containing an E2A motif mapped to the intronic region of the Pml (promyelocytic leukemia protein) gene locus (Figure 5E). As a tumor suppressor, Pml is essential for HSC maintenance and its deficiency affects all hematopoietic lineages in recipient mice after BM transplant (Ito et al., 2008). The core promoter of Itpkb is a site of potential co-occupancy by LncHSC-2 and TFs Erg, Pu.1, Fli1 and Meis1 (Figure 5E). Mice lacking Itpkb, the B isoform of the Ins(1,4,5)P3 3-kinase, have a complete and specific T cell deficiency because of a developmental block at the double-positive thymocyte stage (Pouillon et al., 2003). Other LncHSC-2 co-occupied promoter regions include Cox5b, Itgb2, Tnf, and Slc35c2 (Figure S5B).

Since motif analysis showed that lncHSC-2 binding sites are highly enriched for E2A binding, we wonder whether LncHSC-2 is involved in recruiting E2A to its target sites. To address this question, we analyzed previous ChIP-seq data for E2A binding in HPC7 cells and found that there are almost 20 binding peaks overlapped between E2A and LncHSC-2 (Table S5). From them we selected three sites with the highest scores of enrichment, which are close to gene Nln, Slc35c2 and Itgb2, respectively. Interestingly, ChIP-qPCR showed that E2A binding on these sites was abrogated after LncHSC-2 KD (Figure 5F), suggesting that LncHSC-2 is directly involved or responsible for E2A binding on some target sites.

Recent studies have implicated transposable elements such as ERVs and LTRs in the evolution, regulation, as well as function of lncRNAs (Kapusta et al., 2013; Kelley and Rinn, 2012). To measure whether LncHSC-2 was enriched at any classes of repetitive elements, we performed peak calling again with both unique and multiple-mapped paired-end reads (including up to two alignments). The results show that LncHSC-2 binding sites are specifically enriched for ERVL-MaLR LTR families of repeats and depleted of LINE (L1), SINE (B4, Alu), and Simple repeats (Figure S5C and Table S6).

Discussion

In this study, we carried out a comprehensive RNA-seq analysis in purified HSCs, differentiated B cells and Granulocytes. We discovered 2,614 known lncRNAs and almost 500 unannotated transcripts expressed in HSCs. This list contains almost all the lncRNAs identified from the previous study (Cabezas-Wallscheid et al., 2014), but is more comprehensive. Furthermore, we performed a series of analyses to characterize those lncRNAs, including examining their conservation, overlap with repeats, and their correlation with DNA methylation and histone marks.

Although the known lncRNAs may play important functions for HSCs, in this study we specifically focused on previously unannotated transcripts and identified 159 high-confidence LncHSCs, as compared with the representative differentiated lineages of B cell and Granulocytes. Among them, we demonstrated that LncHSC-1 and LncHSC-2 are located in the nucleus, and differentially expressed between WT and Dnmt3a KO HSCs. KD of LncHSC1/2 revealed that LncHSC-1 is involved in myeloid differentiation, and LncHSC-2 is involved in HSC self-renewal and T cell differentiation. Moreover, we determined that LncHSC-2 bind sites are enriched for the hematopoietic-specific TF binding sites, especially E2A, which is a well-recognized regulator of hematopoietic differentiation.

How complete is our catalog of potential HSC-specific LncRNAs?

Here we used extremely deep sequencing data (>1.3 billion HSC reads when combined) to detect lncRNA expression in HSCs. The number of transcripts that are truly unique to HSCs could be reduced if similarly deep sequencing was performed across additional hematopoietic lineages, and if LncRNAs shared with progenitors were eliminated. On the other hand, our filtering criteria were highly stringent, including size, splicing, and expression level criteria, and we excluded putative lncRNAs that overlapped with protein-coding genes and their extended 3′UTRs, even when they were predicted by splice motif analysis to be transcribed in the opposite direction of the associated coding gene. In this regard, all the lncRNAs identified in our study are intergenic, which may underestimate the number of bona fide HSC-specific lncRNAs. Finally, our use of poly-A+ RNA and filtering criteria likely excludes many enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) (Natoli and Andrau, 2012), another interesting set of non-coding RNAs. Thus, with this comprehensive but conservative approach, we can expect these 159 LncHSCs, due to their low expression in most other tissues (Figure 1), are unlikely to have been discovered using any other approach. This relatively small number (total ~300 HSC-specific LncRNAs including those previously already annotated) is aligned with the small number of protein coding genes (~300) thought to be uniquely expressed in HSCs compared to other blood lineages (Chambers et al., 2007), and is larger than the number of B cell– or granulocyte-specific lncRNAs, perhaps suggesting their particular roles in primitive cells.

Functional characterization of LncHSCs

More data on the functional relevance of lncRNAs will be needed to understand their importance relative to protein coding genes. About two-thirds (116/152) of reported protein coding gene KOs result in some degree of hematopoietic defect after HSC or bone marrow transplantation (Rossi et al., 2012). Here, both of the two LncHSCs we tested in vivo showed an impact on lineage differentiation, while LncHSC-2 showed an effect on self-renewal after KD and transplantation. Although the shRNAs we used here provide an efficient strategy for initial screening, further confirmation of these phenotypes using complete ablation, as well as rescue experiments, would be of value in the future.

In addition to functional studies, mapping the binding sites of LncHSC–2 using ChIRP-seq revealed they are enriched for TF binding sites. KD of LncHSC-2 blocked E2A binding on some target sites suggested that LncHSC-2 is involved in TF binding. Whether LncHSC-2 directly binds to TF or through other complex to recruit them would need to be further investigated.

Although LncRNAs are recognized as being less conserved across species than coding genes, we identified a human syntenic region with several putative lncRNAs that changed in DNMT3A-mutant AML patients in concordance with changes in similarly localized transcripts in mouse Dnmt3a KO HSCs. Whether these LncHSCs contribute to disease development remains to be determined, but the frequent mutation of DNMT3A in AML (Ley et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2011) and other hematologic malignancies (Goodell and Godley, 2013), and the observation that >50% of LncHSCs change in expression after Dnmt3a KO suggest this relationship warrants further investigation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Please see Supplementary Information online for more extensive methods

HSC purification

Whole bone marrow cells were isolated from mouse femurs, tibias, pelvis and humerus. LT-HSCs were purified using the side population (SP) method as previously described (Goodell et al., 1996), in conjunction with cell surface markers: Lineage− (CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, Gr1, Mac1 and T119) Sca-1+ c-Kit+ CD150+.

RNA Sequencing

RNA was isolated from FACS-sorted HSCs with the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen). Paired end libraries were generated with Illumina TruSeq RNA kit. Alignment was performed by RUM (Grant et al., 2011). Cufflinks and Cuffdiff (Trapnell et al., 2010) were used for transcript reconstruction, quantification, and differential expression analysis.

shRNA cloning and viral transduction

Oligos targeting each desired transcript were cloned by BLOCK-iT PolII miR RNAi Expression Vector Kit (Invitrogen). The oligos were further recombined into the retroviral MSCV-RFB vector. For retroviral transduction of hematopoietic progenitors, the suspension was spin-infected at 250 × g at room temperature for 2 hours in the presence of polybrene (4 μg/ml). For in vivo transplantation, cells were incubated for a further 1 hour at 37°C. For in vitro assays, transduced cells were cultured in fresh transduction medium for a further two days.

In vivo Transplantation

C57Bl/6 CD45.1 mice were transplanted by retro-orbital injection following a split dose of 10.5 Gy of lethal irradiation. 50,000 Sca-1+ (CD45.2) donor cells were injected to the recipient mice. For secondary transplantation, 500 CD45.2+GFP+ KSL cells from primary recipients were resorted 20 weeks after transplantation and mixed with 250,000 CD45.1 WBM cells, and injected into new lethally irradiated recipients.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Single molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed using the QuantiGene ViewRNA ISH Cell Assay according to manufacturer’s instruction (Affymetrix). Images were taken on API Deltavision Deconvolution Microscope (Applied precision).

ChIRP

ChIRP was performed as described previously (Chu et al., 2011).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants: 5T32AI007495, AG036562, AG28865 CA126752, DK092883, DK084259, CPRIT grant RP110028 and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation. to W.L.: CPRIT RP110471, DOD W81XWH-10-1-0501 and NIH R01HG007538. We thank the Cytometry and Cell Sorting (AI036211, CA125123, and RR024574), the Genomic and RNA Profiling (grant CA125123) and Integrated Microscopy (HD007495, DK56338, and CA125123) cores at Baylor College of Medicine.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L. and M.J. designed, performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. D.S. and H.J. analyzed the RNA-seq data. B.R. analyzed RNA-seq and CHIRP-seq data and wrote the manuscript. Z.X. analyzed TCGA RNA-seq data. L.Y. and X.T. performed validation experiments. K.S. made over-expression constructs. G.A.D. supervised the research and data interpretation. W.L. supervised the bioinformatic analyses. M.A.G. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez-Dominguez JR, Hu W, Yuan B, Shi J, Park SS, Gromatzky AA, van Oudenaarden A, Lodish HF. Global discovery of erythroid long noncoding RNAs reveals novel regulators of red cell maturation. Blood. 2014;123:570–581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-530683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas-Wallscheid N, Klimmeck D, Hansson J, Lipka DB, Reyes A, Wang Q, Weichenhan D, Lier A, von Paleske L, Renders S, et al. Identification of regulatory networks in HSCs and their immediate progeny via integrated proteome, transcriptome, and DNA Methylome analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challen GA, Sun D, Jeong M, Luo M, Jelinek J, Berg JS, Bock C, Vasanthakumar A, Gu H, Xi Y, et al. Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 2012;44:23–31. doi: 10.1038/ng.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers SM, Boles NC, Lin KY, Tierney MP, Bowman TV, Bradfute SB, Chen AJ, Merchant AA, Sirin O, Weksberg DC, et al. Hematopoietic fingerprints: an expression database of stem cells and their progeny. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:578–591. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, Guernec G, Martin D, Merkel A, Knowles DG, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Pandya-Jones A, McDonel P, Shishkin A, Sirokman K, Surka C, Kadri S, Xing J, Goren A, Lander ES, et al. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science. 2013;341:1237973. doi: 10.1126/science.1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Godley LA. Perspectives and future directions for epigenetics in hematology. Blood. 2013;121:5131–5137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-427724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GR, Farkas MH, Pizarro AD, Lahens NF, Schug J, Brunk BP, Stoeckert CJ, Hogenesch JB, Pierce EA. Comparative analysis of RNA-Seq alignment algorithms and the RNA-Seq unified mapper (RUM) Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2518–2528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G, Young G, Lucas AB, Ach R, Bruhn L, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Rinn JL. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature. 2012;482:339–346. doi: 10.1038/nature10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah R, Joshi A, Wilson NK, Kinston S, Gottgens B. A compendium of genome-wide hematopoietic transcription factor maps supports the identification of gene regulatory control mechanisms. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Yuan B, Flygare J, Lodish HF. Long noncoding RNA-mediated anti-apoptotic activity in murine erythroid terminal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2573–2578. doi: 10.1101/gad.178780.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung T, Wang Y, Lin MF, Koegel AK, Kotake Y, Grant GD, Horlings HM, Shah N, Umbricht C, Wang P, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Bernardi R, Morotti A, Matsuoka S, Saglio G, Ikeda Y, Rosenblatt J, Avigan DE, Teruya-Feldstein J, Pandolfi PP. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2008;453:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature07016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga E, Nanri T, Mitsuya H, Asou N. Mutation in the RNA binding protein TIS11D/ZFP36L2 is associated with the pathogenesis of acute leukemia. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong M, Sun D, Luo M, Huang Y, Challen GA, Rodriguez B, Zhang X, Chavez L, Wang H, Hannah R, et al. Large conserved domains of low DNA methylation maintained by Dnmt3a. Nat Genet. 2014;46:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta A, Kronenberg Z, Lynch VJ, Zhuo X, Ramsay L, Bourque G, Yandell M, Feschotte C. Transposable elements are major contributors to the origin, diversification, and regulation of vertebrate long noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley D, Rinn J. Transposable elements reveal a stem cell-specific class of long noncoding RNAs. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-11-r107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, Bradley RK, Fields PA, Steinhauser ML, Ding H, Butty VL, Torrey L, Haas S, et al. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechman ER, Gentner B, van Galen P, Giustacchini A, Saini M, Boccalatte FE, Hiramatsu H, Restuccia U, Bachi A, Voisin V, et al. Attenuation of miR-126 activity expands HSC in vivo without exhaustion. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, Payton JE, Baty J, Welch J, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli G, Andrau JC. Noncoding transcription at enhancers: general principles and functional models. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Gibson WS, Balazs AB, Baltimore D. MicroRNAs enriched in hematopoietic stem cells differentially regulate long-term hematopoietic output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14235–14240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Nicoll J, Paquette RL, Baltimore D. Sustained expression of microRNA-155 in hematopoietic stem cells causes a myeloproliferative disorder. J Exp Med. 2008;205:585–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paralkar VR, Mishra T, Luan J, Yao Y, Kossenkov AV, Anderson SM, Dunagin M, Pimkin M, Gore M, Sun D, et al. Lineage and species-specific long noncoding RNAs during erythro-megakaryocytic development. Blood. 2014;123:1927–1937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto do OP, Richter K, Carlsson L. Hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells immortalized by Lhx2 generate functional hematopoietic cells in vivo. Blood. 2002;99:3939–3946. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouillon V, Hascakova-Bartova R, Pajak B, Adam E, Bex F, Dewaste V, Van Lint C, Leo O, Erneux C, Schurmans S. Inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate is essential for T lymphocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1136–1143. doi: 10.1038/ni980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, Dhanasekaran SM, Cao Q, Brenner JC, Laxman B, Asangani IA, Grasso CS, Kominsky HD, et al. Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:742–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi L, Lin KK, Boles NC, Yang L, King KY, Jeong M, Mayle A, Goodell MA. Less is more: unveiling the functional core of hematopoietic stem cells through knockout mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semerad CL, Mercer EM, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Murre C. E2A proteins maintain the hematopoietic stem cell pool and promote the maturation of myelolymphoid and myeloerythroid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1930–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigova AA, Mullen AC, Molinie B, Gupta S, Orlando DA, Guenther MG, Almada AE, Lin C, Sharp PA, Giallourakis CC, et al. Divergent transcription of long noncoding RNA/mRNA gene pairs in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2876–2881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221904110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MD, Wang CI, Kharchenko PV, West JA, Chapman BA, Alekseyenko AA, Borowsky ML, Kuroda MI, Kingston RE. The genomic binding sites of a noncoding RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20497–20502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113536108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpo DJ, Broxmeyer HE, Ward T, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Chung YJ, Shelley WC, Richfield EK, Ray MK, Yoder MC, et al. Targeted disruption of Zfp36l2, encoding a CCCH tandem zinc finger RNA-binding protein, results in defective hematopoiesis. Blood. 2009;114:2401–2410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallack MR, Magor GW, Dartigues B, Sun L, Huang S, Fittock JM, Fry SV, Glazov EA, Bailey TL, Perkins AC. Novel roles for KLF1 in erythropoiesis revealed by mRNA-seq. Genome Res. 2012;22:2385–2398. doi: 10.1101/gr.135707.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trubia M, Albano F, Cavazzini F, Cambrin GR, Quarta G, Fabbiano F, Ciambelli F, Magro D, Hernandezo JM, Mancini M, et al. Characterization of a recurrent translocation t(2;3)(p15–22;q26) occurring in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:48–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman A, He XC, Thorvaldsen JL, Sugimura R, Perry JM, Tao F, Zhao M, Christenson MK, Sanchez R, Yu JY, et al. Maternal imprinting at the H19-Igf2 locus maintains adult haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;500:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner LA, Christensen CJ, Dunn DM, Spangrude GJ, Georgelas A, Kelley L, Esplin MS, Weiss RB, Gleich GJ. EGO, a novel, noncoding RNA gene, regulates eosinophil granule protein transcript expression. Blood. 2007;109:5191–5198. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Park HJ, Dasari S, Wang S, Kocher JP, Li W. CPAT: Coding-Potential Assessment Tool using an alignment-free logistic regression model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NK, Foster SD, Wang X, Knezevic K, Schutte J, Kaimakis P, Chilarska PM, Kinston S, Ouwehand WH, Dzierzak E, et al. Combinatorial transcriptional control in blood stem/progenitor cells: genome-wide analysis of ten major transcriptional regulators. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, Pan CM, Lu G, Shen Y, Shi JY, Zhu YM, Tang L, Zhang XW, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:309–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim E, Kirby JE, Brown DE, Mercier FE, Sadreyev RI, Scadden DT, Lee JT. Xist RNA is a potent suppressor of hematologic cancer in mice. Cell. 2013;152:727–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Prak L, Rayon-Estrada V, Thiru P, Flygare J, Lim B, Lodish HF. ZFP36L2 is required for self-renewal of early burst-forming unit erythroid progenitors. Nature. 2013;499:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature12215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lian Z, Padden C, Gerstein MB, Rozowsky J, Snyder M, Gingeras TR, Kapranov P, Weissman SM, Newburger PE. A myelopoiesis-associated regulatory intergenic noncoding RNA transcript within the human HOXA cluster. Blood. 2009;113:2526–2534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.