Abstract

DiGeorge syndrome is an immunodeficient disease associated with abnormal development of 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches. As a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11.2 occurs, various clinical phenotypes are shown with a broad spectrum. Conotruncal cardiac anomalies, hypoplastic thymus, and hypocalcemia are the classic triad of DiGeorge syndrome. As this syndrome is characterized by hypoplastic or aplastic thymus, there are missing thymic shadow on their plain chest x-ray. Immunodeficient patients are traditionally known to be at an increased risk for malignancy, especially lymphoma. We experienced a 7-year-old DiGeorge syndrome patient with mediastinal mass shadow on her plain chest x-ray. She visited Severance Children's Hospital hospital with recurrent pneumonia, and throughout her repeated chest x-ray, there was a mass like shadow on anterior mediastinal area. We did full evaluation including chest computed tomography, chest ultrasonography, and chest magnetic resonance imaging. To rule out malignancy, video assisted thoracoscopic surgery was done. Final diagnosis of the mass which was thought to be malignancy, was lymphoproliferative lesion.

Keywords: DiGeorge syndrome, Lymphoproliferative disorders, Mediastinal neoplasms

Introduction

DiGeorge syndrome is an immunodeficient disease with especially defect in cellular immunity. Signs and symptoms are associated with abnormal development of 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches. As these sites are common embryonic precursor for the thymus and parathyroid, they can cause immunologic problems1). The most common manifestations are cardiac malformations, speech delay, and immune deficiency but wide phenotypic spectrum of neuropsychiatric disorders and otolaryngological disorders also exists. Dysmorphogenesis of pharyngeal pouches occurs during early embryogenesis is known to play a main role in these manifestations2,3). As the etiology is heterogeneous, spectrum is broad of the syndrome. As the clinical phenotype vary widely, there can be no symptoms other than immunologic problem4). Current estimates of the prevalence reach as frequent as 1 in every 2,000 people in America5). In Korea, the prevalence is 0.50 per million6). These patients are at increased risk for lymphoproliferative disorders and even malignancy, such as T-cell and B-cell lymphomas7,8). We present our experience with a case with DiGeorge syndrome, who developed lymphoproliferative disease.

Case report

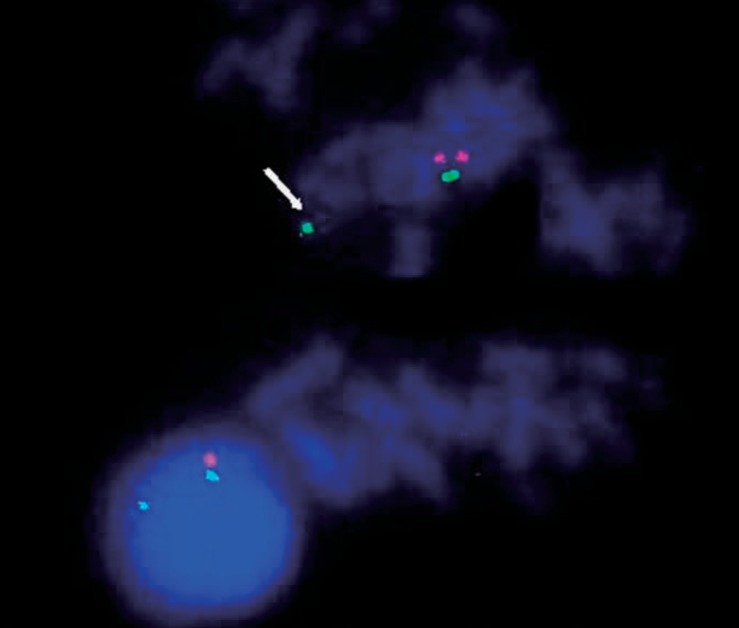

A 7-year-old female, delivered at intrauterine period 38 weeks, 2.9 kg, by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery in another hospital, was diagnosed with DiGeorge's syndrome at 2 weeks of birth by chromosomal assay (Fig. 1) following a hypocalcemic seizure. At that time, there was missing thymic shadow on her chest x-ray. There was no cardiac anomaly with presence of minimal patent ductus arteriosus. She initially came to our hospital for rehabilitation outpatient treatment at the age of 10 months. She visited pediatric department frequently because of recurrent pneumonia and upper respiratory tract infection.

Fig. 1. This is our patient's chromosomal assay. Fluorescence in situ hybridization test was done, and it shows only one TUPLE1 signal at ch' 22. This represents interstitial deletion of 22q11.2, DiGeorge critical region (arrow).

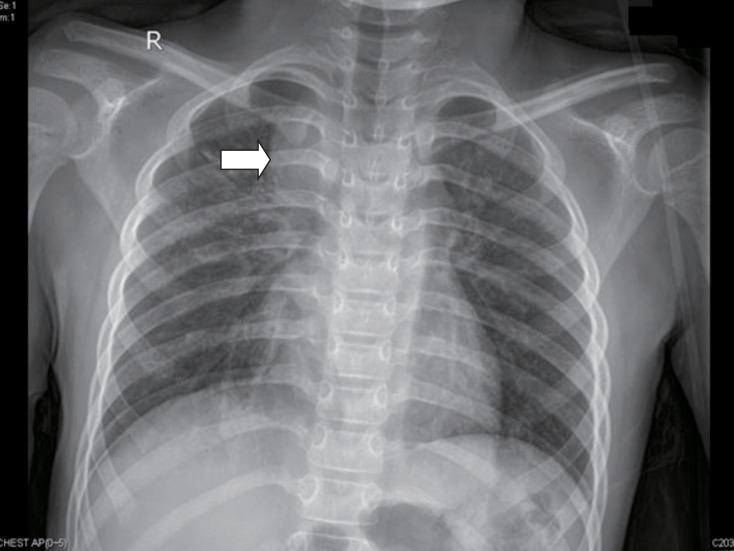

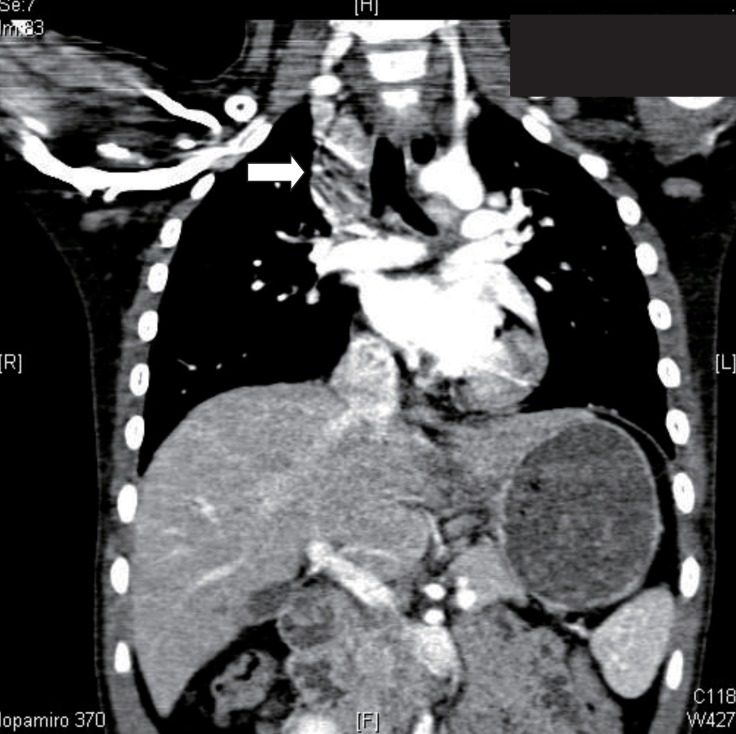

At 7 years of age, she was admitted for pneumonia. Comparing with her initial chest x-ray, a bulging contour of mediastinal shadow was noted on the follow, initially thought to be an enlarged thymus (Fig. 2). As her previous chest ultrasonography reviewed no thymus, we first considered chest computed tomography (CT) for further evaluation. There was no abnormal blood test except mild leukocytosis, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein which thought to be the result of infection. On her chest CT, ovoid enhancing lesion (1.5 cm×2.2 cm×2.3 cm) in right paratracheal area was seen (Fig. 3), and chest sonography was recommended.

Fig. 2. Chest x-ray was taken when she had pneumonia. It shows homogenous mass like lesion on right mediastinal area (arrow).

Fig. 3. Chest computed tomography shows an ovoid enhancing lesion (1.5 cm×2.2 cm×2.3 cm) in right paratracheal area (arrow).

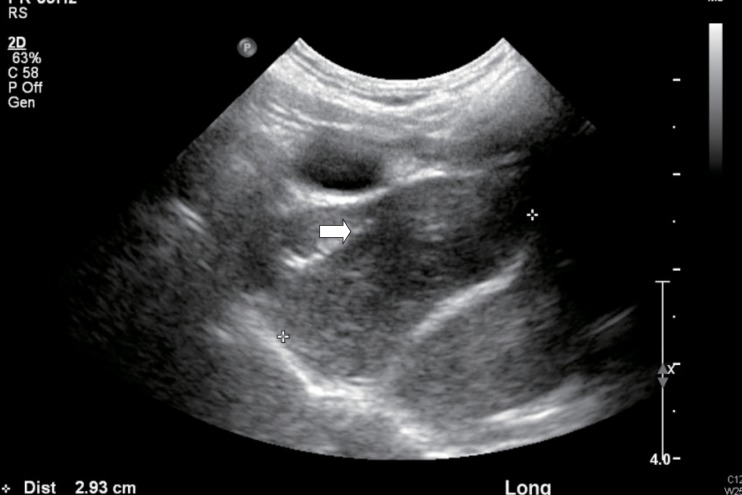

Chest ultrasonography was done. The ovoid enhancing lesion that was seen on the chest CT was a slightly hyperechoic lesion on ultrasonography. Parenchymal echogenic pattern of the thymus was not seen (Fig. 4). As it was a nonspecific finding, excluding thymus was impossible. Follow-up evaluations showed up, mass size showed slight decrease as her pneumonia improved.

Fig. 4. Chest ultrasonography shows a slightly hyperechoic lesion (arrow).

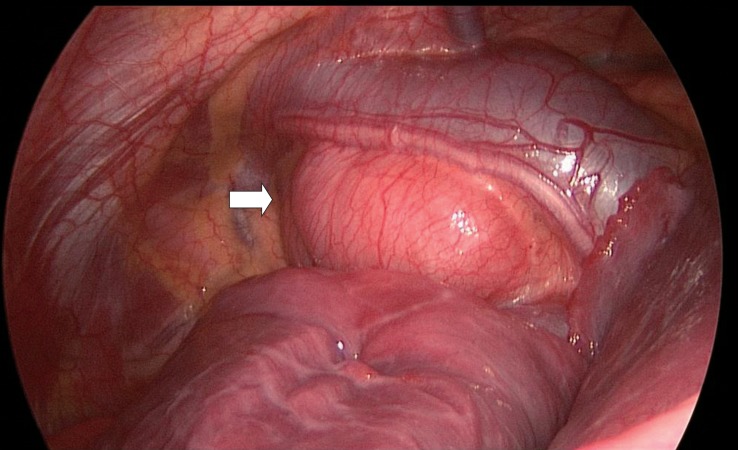

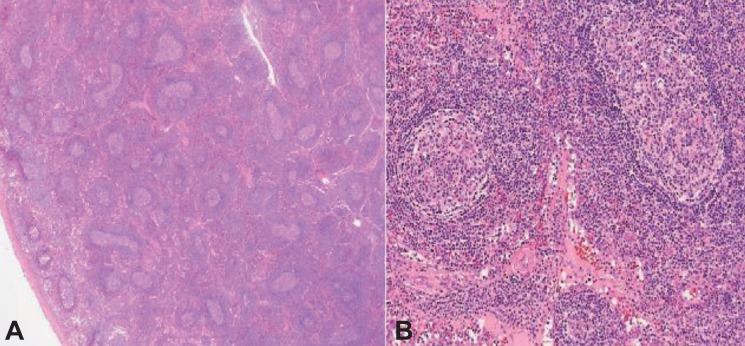

Regular checkup was done through 6 months. Mass shadow still existed, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was recommended. Size of right upper paratracheal mass and lymph nodes were increased. According to the MRI image, there were pneumonic consolidation on both lung fields, and increased size of right upper paratracheal mass and lymphnodes. Lymphoma or lymphoproliferative disorder was suspected. Biopsy was recommended. Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery was done. The thoracic scope showed a 2-cm-sized solid mass in anterior mediastinal mass between superior vena cava and aortic arch was observed (Fig. 5). There was no adhesion or effusion. The mass was removed without any complication, and pathologic review was done. No immunological stain was done. Numerous enlarged follicles were irregularly distributed in various sizes and shapes. Reactive follicles showed well demarcated mantle zone and germinal center (Fig. 6). As it showed normal architecture of lymph node with reactive hyperplasia and there was no evidence of specific infection, special stain was not done. Final diagnosis was lymphoproliferative lesion.

Fig. 5. Thorasic scope shows a 2-cm-sized solid mass in anterior mediastinal mass between superior vena cava and aortic arch (arrow).

Fig. 6. (A) Pathologic finding shows numerous enlarged follicles with irregularly distributed of various sizes and shapes (H&E, ×100). (B) Reactive follicles show well demarcated mantle zone and germinal center (H&E, ×400).

Discussion

In 1965, Angelo DiGeorge described the common embryologic derivation of the heart, thymus and parathyroid glands as the explanation for their joint malformation in patients and named DiGeorge syndrome. As a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11.2 occurs, various clinical phenotypes are shown with a broad spectrum3). The classic triad of this syndrome includes conotruncal cardiac anomalies, hypoplastic thymus, and hypocalcemia. Most of these patients show mildly or moderately diminished circulating T cells. Despite their infrequent cellular immunity, as medical science develops, the patient desired life expectancy extended. Their concern is now complications that can show up as they become older, such as cancer.

Traditionally, immunodeficient patients are known to be at an increased risk for malignancy, especially lymphoma. There are three general biologic circumstances: (1) Endemic incidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection, (2) predominancy of type 2 cytokine production in susceptible hosts and in the case of primary immune defects, and (3) disruption of normal pathways that regulate lymphocyte cell cycling and survival by genetic mutations9).

Serious T-cell defects increases risk of lymphoma. Also chronic inflammation occurring as a result of infection in immunodeficeint patient has oncogenic properties10). The hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11.2 generally includes the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene (COMT). As COMT function is altered, the ability to detoxify certain environmental carcinogens is altered11). It means that DiGeorge syndrome patients are at increased risk for lymphoma. There are some cases of malignancy related with DiGeorge syudrome, but lymphoproliferative disorder related cases have not been reported.

In our case, there was a mass like lesion on mediastinum but as it with wax and wane feature, we just follow up her chest x-ray. But at the last chest x-ray follow-up, the size became larger. We underwent chest sonography, chest CT, and chest MRI. Biopsy was recommended to rule out lymphoma. At the operating field, mass was removed readily, and no malignant evidence was shown. The pathologic finding was also far from malignancy, a lymphoproliferative lesion.

Lymphoproliferative disorders show reactive or atypical lymphoid hyperplasia. In our patient, there was only repetitive infection which can be seen in DiGeorge syndrome, and a mass like shadow on plan chest x-ray. Prognosis of lymphoproliferative disease is generally good, and our patient will have a good prognosis as well. But there are still opportunities for malignancy. Therefore, continuous follow-up is needed. In conclusion, we report a rare case with lymphoproliferative disease in DiGeorge syndrome.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Chinnadurai S, Goudy S. Understanding velocardiofacial syndrome: how recent discoveries can help you improve your patient outcomes. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;20:502–506. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328359b476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gennery AR. Immunological aspects of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0842-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial Syndrome. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driscoll DA, Budarf ML, Emanuel BS. A genetic etiology for DiGeorge syndrome: consistent deletions and microdeletions of 22q11. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:924–933. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu S, Graf WD, Shprintzen RJ. Genomic disorders on chromosome 22. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:665–671. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328358acd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhim JW, Kim KH, Kim DS, Kim BS, Kim JS, Kim CH, et al. Prevalence of primary immunodeficiency in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:788–793. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.7.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pongpruttipan T, Cook JR, Reyes-Mugica M, Spahr JE, Swerdlow SH. Pulmonary extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosaassociated lymphoid tissue associated with granulomatous inflammation in a child with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome) J Pediatr. 2012;161:954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, Pileri SA. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010;102:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filipovich AH, Mathur A, Kamat D, Kersey JH, Shapiro RS. Lymphoproliferative disorders and other tumors complicating immunodeficiencies. Immunodeficiency. 1994;5:91–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Byrne KJ, Dalgleish AG. Chronic immune activation and inflammation as the cause of malignancy. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:473–483. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated metabolism of catechol estrogens: comparison of wild-type and variant COMT isoforms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6716–6722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]