Abstract

Introduction

Childhood absence epilepsy is an epilepsy syndrome responding relatively well to the ketogenic diet with one-third of patients becoming seizure-free. Less restrictive variants of the classical ketogenic diet, however, have been shown to confer similar benefits. Beneficial effects of high fat, low-carbohydrate diets are often explained in evolutionary terms. However, the paleolithic diet itself which advocates a return to the human evolutionary diet has not yet been studied in epilepsy.

Results

Here, we present a case of a 7-year-old child with absence epilepsy successfully treated with the paleolithic ketogenic diet alone. In addition to seizure freedom achieved within 6 weeks, developmental and behavioral improvements were noted. The child remained seizure-free when subsequently shifted toward a paleolithic diet.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the paleolithic ketogenic diet was effective, safe and feasible in the treatment of this case of childhood absence epilepsy.

Keywords: Childhood absence epilepsy, Evolutionary medicine, Ketogenic diet, Neurology, Paleolithic diet

Introduction

The ketogenic diet is an established and effective non-pharmacological treatment for epilepsy [1]. As a first-line therapy it is recommended in deficiencies of enzymes involved in glucose utilization such as the glucose transporter 1 and the pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency syndromes [2]. Otherwise, the ketogenic diet is recommended when at least two antiepileptic drugs fail. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndromes, however, are responding relatively well to the ketogenic diet [3, 4] with 34 % of absence epilepsy patients becoming seizure-free [5]. Currently, there is a tendency towards the use of less strict but easier-to-follow variants of the classical ketogenic diets, such as the modified Atkins diet and the low glycemic index treatment [5, 6]. In a study by Groomes et al. [5] absence epilepsy responded similarly to the ketogenic diet and the modified Atkins diet. Regarding its macronutrient content the paleolithic diet belongs to the low-carbohydrate diets. Also referred to as the evolutionary diet, the paleolithic diet is increasingly popular since the release of the book of Cordain [7] who is now regarded as the founder of the paleolithic diet. Cordain was greatly inspired by Voegtlin [8] who was the first proponent of the diet as well as Eaton and Konner [9] who introduced the concept into a mainstream journal. The paleolithic diet advocates foods humans are evolutionarily adapted to and excludes those that were not available in pre-agricultural times such as grains, diary, legumes, starchy vegetables, refined sugars, oils rich in omega-6 fatty acids and margarines. In this study, a case of a child diagnosed with absence epilepsy and then successfully treated with a carbohydrate-restricted paleolithic diet, we referred to as the paleolithic ketogenic diet, is reported.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child for being included in the study.

Case Report

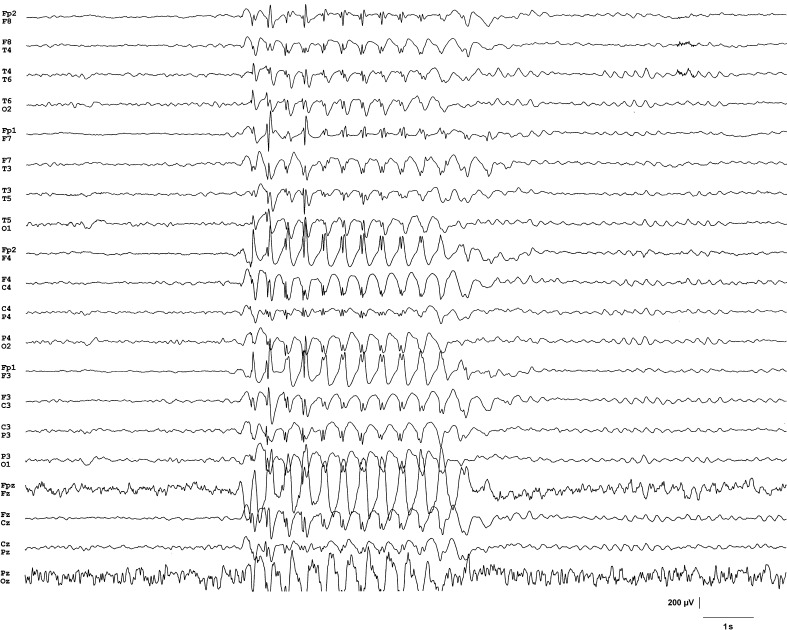

Perinatal history of the 7-year-old child was unremarkable and family history was also negative for epilepsy. She had three febrile convulsions at the ages of 1, 2 and 5 years. Electroencephalograms (EEGs) that were performed subsequently were normal. She was developmentally delayed and was not toilet trained. She had gluten sensitivity and milk allergy. Behaviorally she was withdrawn and unsociable. At age 7 she presented with staring spells with increasing frequency. Six weeks following their onset an EEG examination was carried out which showed frequent trains of generalized spike and wave discharges of 2.5 Hz during both sleep and wakefulness (Fig. 1). Based on electro-clinical features she was diagnosed with childhood absence epilepsy. At this time she had approximately 50 absence seizures a day. She was recommended valproate but her parents refused antiepileptic medication because of concerns of side effects and decided to initiate a dietary therapy. They consulted the last author of this paper who advised the paleolithic ketogenic diet consisting of only meat, offal, fish, egg and animal fat without calorie restriction (Table 1). Fat meats were encouraged over lean meats to approximate a 4:1 fat to protein ratio (in grams). Diet was supplemented with vitamin D3 (2,000 IU/day) and omega3 fatty acids (500 mg/day). This restrictive diet was maintained for 3 months with the child completely adhering to the diet. The diet was well-tolerated and no adverse effects emerged. There was a gradual reduction in the number of seizures from the very first week. At 6 weeks on the diet the child became seizure-free. A laboratory blood test carried out at this time showed normal laboratory parameters with the exception of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol which were moderately elevated (Table 2). Serum glucose was 3.2 mmol/l thus within the range also targeted by the classical ketogenic diet regime. Other laboratory parameters were normal. At 3 months on the diet she was advised to gradually increase carbohydrate intake mostly in the form of low glycemic index vegetables. Other restrictions of the paleolithic diet were maintained. A blood test carried out at 14 months indicated that most laboratory parameters were still in the normal range while total cholesterol level remained elevated (Table 2). Although her weight and height did not change during the preceding 2 years, at 4 months on the diet she had gained 3 kg and grown 6 cm (from 19 to 22 kg and from 110 to 116 cm). Parents also reported improvements in mood and social functioning. Earlier she was described as a child with special needs in education. Currently, she is attending a regular school and performing well. She became toilet trained for daytime, however, nocturnal enuresis remained. Long-term video-EEG encompassing a whole-night sleep was performed at 12 months of diet therapy. The EEG (inspected by Z.C. and A.K.) revealed physiological sleep structure and no signs of epileptic activity. At the time of writing this publication she has been on the diet for 20 months and is seizure-free.

Fig. 1.

An example of waking electroencephalogram showing a train of 2.5 Hz generalized spike and wave discharges at the time of the diagnosis

Table 1.

Sample daily menus

| Paleolithic ketogenic daily menu |

|---|

| Breakfast: scrambled eggs fried in lard |

| Snack: pork greaves |

| Lunch: chuck roast |

| Snack: smoked sausage |

| Dinner: beef steak |

| Paleolithic daily menu |

|---|

| Breakfast: fried eggs, cucumber |

| Snack: pork greaves |

| Lunch: roasted sausage |

| Snack: dry sausage |

| Dinner: roasted chicken leg, cauliflower puree |

Processed meats in the diet were homemade with no gluten, soy, carbohydrate or chemicals added. Cooked meat was prepared using abundant amounts of animal fat

Table 2.

Laboratory data while on the paleolithic ketogenic diet (at 6 weeks after diet initiation) and on the paleolithic diet (at the 14th month)

| Paleolithic ketogenic diet | Paleolithic diet | |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D (25(OH)D) (ng/ml) | 31.5 | – |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 142 | 137 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 4.1 | – |

| Chloride (mmol/l) | 103 | 97 |

| Carbamide (mmol/l) | 5 | 8.9 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/l) | 375 | 274 |

| Total protein (g/l) | 68 | – |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 7.6 | 7.5 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 0.84 | 1.13 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.58 | 2.26 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.85 | – |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 31 | 35 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 254 | 179 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.43 | 2.45 |

| Phosphor (mmol/l) | 1.49 | – |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 0.6 | 1 |

| Iron (μmol/l) | 16 | 11 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 125 | 134 |

Dashes indicate that the given parameter was not measured

HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein

Discussion

Variants of the classical ketogenic diet have been reported to have an effect close to that of the classical ketogenic diet while being more feasible [5, 6]. Efficacy of low-carbohydrate diets is often interpreted in evolutionary terms implicating that humans are well-adapted to ketosis [10]. However, the paleolithic diet itself, which advocates a return to the evolutionary adapted diet, has not yet been studied in epilepsy. The paleolithic diet is gaining popularity worldwide as well as in Hungary mainly due to the books of Cordain [7] and in Hungary due to Szendi [11] and Tóth [12]. In his book, Szendi synthesized knowledge from several sources of medical literature to support the paleolithic diet while Tóth summarized his experience as a physician with an evolutionary attitude. Studies of short-term dietary intervention with the paleolithic diet indicated significant metabolic benefits in healthy controls as well as in diabetic patients [13–16]. Epidemiological and clinical studies of ancestral populations demonstrate an absence or very rare occurrence of western civilization disorders including neurological diseases [13].

In childhood absence epilepsy valproate and ethosuximide are the antiepileptic drugs of first choice. In this case, the parents of the child refused antiepileptic medication and therefore the paleolithic ketogenic diet was initiated as a stand-alone therapy. The diet resulted in a rapid decrease of absence seizures. Seizure freedom was maintained when gradually shifted towards increased carbohydrate intake at 3 months. In addition to seizure control the diet conferred additional benefits including improved behavior and developmental gains. Behavioral benefits are also seen in the classical ketogenic diet [17]. However, in contrast to weight loss and retarded growth, major adverse effects of the classical ketogenic diet [18], our patient did gain weight and height. In this case no apparent adverse effects were noted. As reported by the parents, maintaining the diet, even in the ketogenic phase, was relatively easy for the child without dislike for meat and animal fat. Although childhood absence epilepsy is regarded as a form of epilepsy most patients grow out of, cessation of absence seizures within weeks of diet onset suggests an effect of the diet and not the passage of time. Despite seizure freedom maintained for the last 18 months and the negative EEG, the family is insisting on continuing the paleolithic diet.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the paleolithic ketogenic diet followed by a less carbohydrate-restrictive paleolithic diet was effective, safe and feasible in the treatment of this patient with childhood absence epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge constructive comments on the manuscript received from Dr. Björn Merker. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. Zsófia Clemens is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Zsófia Clemens, Anna Kelemen, András Fogarasi and Csaba Tóth declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Kossoff EH. More fat and fewer seizures: dietary therapies for epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:415–420. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00807-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kossoff EH. International consensus statement on clinical implementation of the ketogenic diet: agreement, flexibility, and controversy. Epilepsia. 2008;49:11–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thammongkol S, Vears DF, Bicknell-Royle J, Nation J, Draffin K, Stewart KG, Scheffer IE, Mackay MT. Efficacy of the ketogenic diet: which epilepsies respond? Epilepsia. 2012;53:e55–e59. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kossoff EH, Henry BJ, Cervenka MC. Efficacy of dietary therapy for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26:162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groomes LB, Pyzik PL, Turner Z, Dorward JL, Goode VH, Kossoff EH. Do patients with absence epilepsy respond to ketogenic diets? J Child Neurol. 2011;26:160–165. doi: 10.1177/0883073810376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda MJ, Turner Z, Magrath G. Alternative diets to the classical ketogenic diet—can we be more liberal? Epilepsy Res. 2012;100:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordain L. The paleo diet: lose weight and get healthy by eating the food you were designed to eat. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voegtlin WL. The stone age diet: based on in-depth studies of human ecology and the diet of man. New York: Vantage Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton SB, Konner M. Paleolithic nutrition—a consideration of its nature and current implications. N Eng J Med. 1985;312:283–289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine EJ, Segal-Isaacson CJ, Feinman R, Sparano J. Carbohydrate restriction in patients with advanced cancer: a protocol to assess safety and feasibility with an accompanying hypothesis. Commun Oncol. 2008;5:22–26. doi: 10.1016/S1548-5315(11)70179-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szendi G. Paleolithic nutrition (Paleolit táplálkozás) Budapest: Jaffa; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tóth C. Paleolithic medicine (Paleolit orvoslás) Budapest: Jaffa; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindeberg S. Food and western disease: health and nutrition from an evolutionary perspective. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Österdahl M, Kocturk T, Koochek A, Wändell PE. Effects of a short-term intervention with a paleolithic diet in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:682–685. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, Ahrén B, Branell UC, Pålsson G, Hansson A, Söderström M, Lindeberg S. Beneficial effects of a Paleolithic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a randomized cross-over pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frassetto LA, Schloetter M, Mietus-Synder M, Morris RC, Jr, Sebastian A. Metabolic and physiologic improvements from consuming a paleolithic, hunter-gatherer type diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:947–955. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pulsifer MB, Gordon JM, Brandt J, Vining EP, Freeman JM. Effects of ketogenic diet on development and behavior: preliminary report of a prospective study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:301–306. doi: 10.1017/S0012162201000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Rho JM. Ketogenic diets: an update for child neurologists. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:979–988. doi: 10.1177/0883073809337162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]