Abstract

Objective

Situations with potential to motivate positive change in unhealthy behavior have been called ‘teachable moments.’ Little is known about how they occur in the primary care setting.

Methods

Cross-sectional observational design. Audio-recordings collected during 811 physician-patient interactions for 28 physicians and their adult patients were analyzed using Conversation Analysis.

Results

Teachable moments were observed in 9.8% of the cases, and share three features: (1) the presence of a concern that is salient to the patient that is either obviously relevant to an unhealthy behavior, or through conversation comes to be seen as relevant; (2) a link that is made between the patient’s salient concern and a health behavior that attempts to motivate the patient toward change; and (3) a patient response indicating a willingness to discuss and commit to behavior change. Additionally, we describe phenomena related to, but not teachable moments, including teachable moment attempts, missed opportunities, and health behavior advice.

Conclusions

Success of the teachable moment rests on the physician’s ability to identify and explore the salience of patient concerns and recognize opportunities to link them with unhealthy behaviors.

Keywords: health behavior change, primary care, smoking, weight management, prevention, health behavior counseling

1. Introduction

Teachable moment is a colloquially term in health care to describe opportunities to stimulate patient action, particularly with regard to health behavior change.[1–7] Conceptual work defining the phenomenon and empirical testing of its effect are limited.[8–11] Most research retrospectively identifies circumstances in peoples’ lives associated with behavior change.[8–11] McBride and colleagues have proposed a conceptual model for the teachable moment[1, 12] and empirically tested it.[13] They define teachable moments as “cueing events:” naturally occurring health events or circumstances that lead individuals to make health behavior changes. Drawing significantly from the Health Belief Model, [14] this definition of a teachable moment informs research examining the effect of cueing events, such as a cancer diagnosis, on rates of smoking cessation,[1] and the impact of worry about cancer on patients’ participation in a behavioral intervention.[13]

McBride et al acknowledge the important social and interactional dimensions of teachable moments.[1, 13] People do not experience health events in isolation, but make sense of experiences through social interaction and communication with friends, family members, and health professionals.[15] Yet, little is known about how teachable moments occur through social interaction and communication. Understanding this process fills an important gap in understanding this phenomenon and could improve health behavior counseling by helping physicians stimulate behavior change through brief, well-timed counseling.

The purpose of this study is to explore the discourse between physicians and patients and examine the social building blocks of the teachable moment for health behavior change during primary care visits. The primary care setting provides unique opportunities to discuss important health events with the majority of the population.[16, 17] Many patients seen in primary care have multiple health behavior risks[18] and counseling that prompts behavior change could make a difference in patients’ lives.[16, 19–26] Thus, examining primary care visits with patients at risk for unhealthy behaviors where health behavior counseling is observed provides a prime environment for observing this phenomenon as it may occur naturally.

2. Methods

Given the limited knowledge about how teachable moments unfold naturally in primary care, we conducted an observational study and used conversation analysis (CA) to answer the following research questions: 1) Is there evidence for teachable moments arising during primary care visits; and 2) if so, how are teachable moments enacted through the communication between physician and patient?

2.1 Study design and sample

We collected audio recordings during 811 physician-patient interactions. Ninety-four physicians from the Research Association of Practices, a practice-based research network of community-based outpatient primary care practices located in Northeast Ohio, were invited to participate in the study. Forty-one physicians enrolled (44% participation rate). Thirteen enrolled physicians were excluded due to logistical problems with data collection (e.g. low patient volume; distance from the research center). The 28 physician participants were residency trained general practitioners (71% internal medicine; 29% family medicine) and averaged 14 years of practice since completion of residency. Half were female; 16 (57%) were white, 9 (32%) black, 2 Asian, and 1 other race.

2.2 Data collection

Adult patients (aged 18–70) scheduled to see a participating physician during data collection days received a letter inviting their participation in the study. Patients who agreed completed a pre-visit telephone survey to assess health risk for smoking, physical activity, consumption of fruits and vegetables and obesity (see Appendix for survey). On the day of the visit, a field researcher confirmed patient consent, observed and audio-recorded the visit. The field researcher’s presence in the room had minimal influence on the content and activities of the visit[27] and had two important benefits. First, the observer carried the audio-recording device, ensuring high quality recordings. Second, the observer identified visits with health behavior talk to be prioritized for transcription. Audio-recorded medical visits were professionally transcribed. De-identified transcripts were organized in Atlas.ti.[28] The University Hospitals of Cleveland IRB approved the study’s procedures.

2.3 Analysis

A multidisciplinary team that included a conversation analyst, a health services researcher, two masters level medical anthropologists, and a family physician analyzed all data. We examined visits with patients who reported a health behavior risk on the survey and where an at-risk health behavior was discussed because of the likelihood that they would have a teachable moment. In many visits, multiple health behavior risks were discussed. Therefore, discussion of a health behavior topic became the unit of analysis. Across the 811 visits, 541 discussions of health behavior were observed and analyzed.

We used conversation analysis (CA), a grounded approach, to analyze the data. Rooted in ethnomethodology,[29, 30] CA is a method for identifying and describing how, through communication, actions such as accomplishing a teachable moment, are achieved through social interaction.[31–37] For each medical visit examined, we used a group process following the CA method described by Pomerantz and Fehr.[38] First, we reviewed transcripts while listening to the audio-recording and identified all instances of health behavior talk. Next, we categorized physicians’ and patients’ verbal actions (e.g. gathering information, evaluating) for each segment, and identified how each action was accomplished. In CA, analysts take an “unmotivated” approach, meaning that our analysis was not guided by a priori definitions of the teachable moment. Rather, we identified the important features of the health behavior talk, prepared case summaries to document our observations, and identified cross-visit patterns that were then developed into a series of working definitions. We used these definitions to individually analyze a group of cases, meeting weekly to discuss our analyses and make comparisons.

After analyzing more than 50 instances of health behavior talk, we identified four categories of health behavior talk: (1) No health behavior advice –instances in which health behavior status was assessed, but no advice for health behavior change was delivered; (2) Health behavior advice – advice to make health behavior change was delivered, but there was no attempt in this talk, short of the advice itself, to persuade the patient to make the recommended change; (3) In action – the patient and physician discussed a health behavior, but the patient was already in the process of making a behavior change. Typically, the physician congratulated the patient for his or her progress; and 4) Possible teachable moments –where the physician attempted to motivate the patient to change a health behavior by suggesting this would help address the patient’s presenting concern.

We focused further attention on this last category, using the CA methods described above. Two groups of cases emerged. Cases where: 1) physicians’ attempts to motivate patients toward behavior change led patients to make a verbal commitment to change; and 2) physicians’ attempts to motivate patients toward behavior change that were resisted. We looked for deviant cases, those that did not fit into the emergent classification scheme, and identified visits with the potential to become teachable moments. These were instances where patients had a salient concern relevant to a health behavior, but the physician did not link the concern to the health behavior in an attempt to motivate change. We labeled these cases missed opportunities. We shared definitions with study consultants who questioned defining the teachable moment based on analysis of discourse alone, without knowing if patients’ behavior changed. As a group, we decided that patients’ verbal commitment to health behavior change was an action toward actual behavior change, and this verbal commitment was the right evidence to use in our analysis because it was the same evidence physicians would have access to during a visit.

Through this process, we developed a codebook that two supervised research assistants used to code approximately half of the cases. We identified additional ambiguous and deviant cases and further refined our definitions and coding procedure. A third coder, trained to apply the final coding procedure, worked with one of the authors (SF), to review all of the cases and consistently apply these codes. All discussions of health behavior topics were categorized into one of six categories: teachable moment, teachable moment attempt, advice, in action, assessment only, and missed opportunity for health behavior counseling.

In what follows, we describe the teachable moment, teachable moment attempt and missed opportunity in more detail. We identify and describe three cases from our database that are exemplars of each category.

3. Results

Among the 811 patient participants, 733 were at risk for at least one unhealthy behavior: 21% were smokers, 68% overweight or obese, 45% inactive and 57% reported poor fruit and vegetable consumption. Among patients who self-identified as at risk for an unhealthy behavior, 451 of those visits included talk about a health behavior for a total of 548 discussions of health behavior (mean number of discussions = 1.2, std dev .45). Table 1 shows the characteristics of these 451 patients.

Table 1.

Patient and Visit Characteristics (n=451)

| Patient Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (std) | 52.6 (10.3) |

| Sex | |

| Male (%) | 147 (33) |

| Female | 304 (67) |

| Race | |

| African American | 172 (38) |

| White | 256 (57) |

| Other Race | 20 (5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 8 (2) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 139 (31) |

| Some college | 136 (30) |

| College degree | 107 (24) |

| Graduate degree | 69 (15) |

| Health Conditions | |

| Diabetes | 109 (24)† |

| Heart disease | 40 (9) |

| High cholesterol | 214 (48) |

| High blood pressure | 253 (56) |

| None of the above conditions | 94 (21) |

| Self-reported Health Status | |

| Excellent | 46 (10) |

| Very good | 134 (30) |

| Good | 150 (33) |

| Fair | 97 (22) |

| Poor | 24 (5) |

|

| |

| Visit Characteristics | n (%) |

|

| |

| Visit Type | |

| Acute care | 103 (23) |

| Chronic care | 255 (57) |

| Well care | 91 (20) |

| Other | 2 (0.4) |

Multiple responses allowed; percentages add to more than 100%.

3.1 Teachable moments for health behavior change

In primary care, teachable moments are a form of opportunistic counseling that takes advantage of health concerns and events in patients’ lives to increase willingness and commitment to change behavior. Teachable moments are accomplished through the communication between the physician and patient, and share the following features: (1) the presence of a concern that is salient to the patient that either has an obvious health behavior component, or comes to be seen as having one through conversation with the physician; (2) a link that is made between the patient’s salient concern and a health topic or health behavior that the physician uses to motivate the patient toward change; and (3) a response from the patient that indicates commitment toward changing the identified behavior. Case 1 is an example of a teachable moment. A key to the transcript notation is in the appendix.

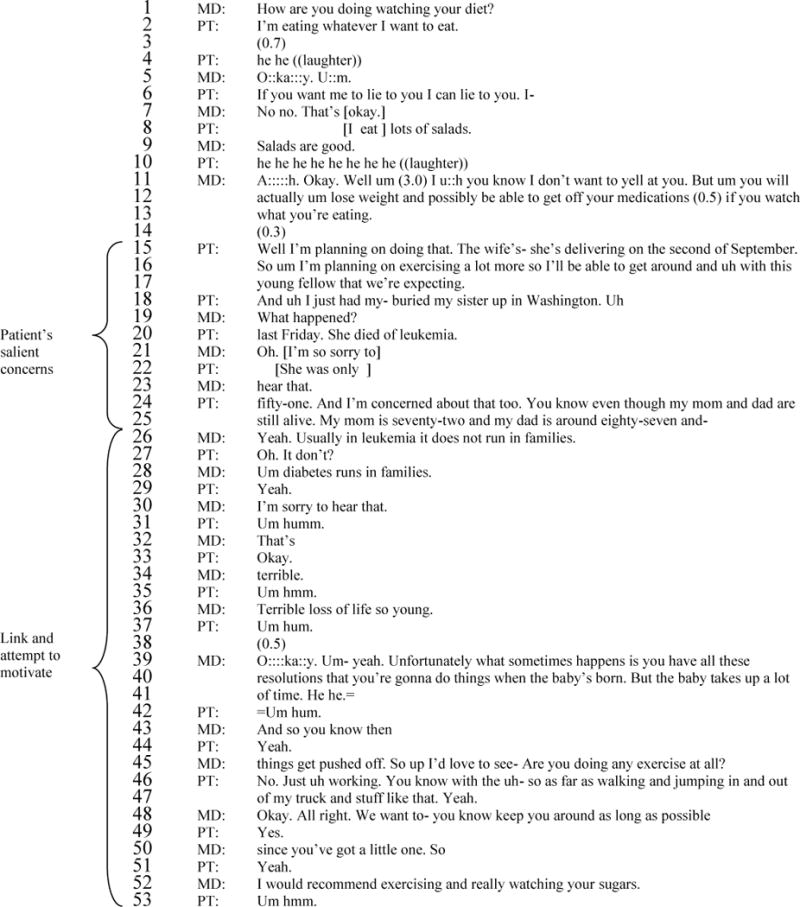

This example of a teachable moment occurs as the physician tries to persuade the patient to change his diet. At the beginning of the segment, the patient expresses little interest in dietary change, first joking (“I’m eating whatever I want to eat” and “If you want me to lie to you I can lie to you. I eat lots of salads.”), then offering a nominal agreement (“I’m planning on doing that.”) before shifting the conversation away from diet toward other topics. Thus, diet is not a topic of importance to this patient at the visit’s beginning. However, other topics are important to the patient, including his wife’s pregnancy, which the patient characterizes as a reason for being healthy (“I’m planning on exercising a lot more so I’ll be able to get around with this young fellow that we’re expecting”) and the recent death of the patient’s sister from leukemia (line 15–25). These are topics the patient raises de novo, and this is evidence that the topics were of particular concern. Thus, his wife’s pregnancy and sister’s death from leukemia are examples of patient salient concerns that have the potential to be leveraged for teachable moments.

Neither of the concerns, however, have an obvious health behavior component. Nevertheless, the physician attempts to redirect the patient’s concern of dying from leukemia to a concern about health behavior. This is accomplished with two pivotal utterances – “Usually in leukemia it does not run in families” (line 26) and “Um diabetes runs in families” (line 28). With the first utterance, the physician addresses the patient’s concern about his sister’s death, implying that the patient need not worry about dying of leukemia. In line 27, the patient responds – ‘Oh. It don’t?’ – showing that the physician correctly addressed his concern. The patient hears the information about leukemia as new information, and changes his thinking about his risk.[39] Next, the physician redirects the patient’s concern about leukemia to another topic – the patient’s diabetes. The physician does this by re-introducing and connecting the topic of diabetes with the patient’s concern about dying from leukemia. These topics are connected by repeating the phrase “runs in families” when referring to both the leukemia and the diabetes, and by the close proximity of the two statements in the conversation. Thus, it can be inferred that the patient should be concerned about dying from diabetes, not from leukemia. In response, we see the patient agree (“Yeah.”) with the physician’s concern about diabetes (line 29), which is not strong evidence that the patient has accepted the salience of this topic, but is evidence that the patient has not yet rejected the topic outright.

Having redirected the patient’s concern to diabetes, the physician moves to bring the topic of health behavior to the floor. The physician builds on the patient’s earlier concern – “We want to- you know keep you around as long as possible since…you’ve got a little one” (lines 48–50) – and then recommends exercising and watching sugar and carbohydrate intake, and offers the patient a referral to a dietician (lines 52–56). In this series of utterances, the physician links the patient’s diabetes and the patient’s salient concern (about dying / staying healthy) with the need for exercise and healthy diet in an attempt to leverage the patient’s concern and motivate change. In response, the patient agrees, first offering a series of “Yes” statements, and then elaborating on the physician’s recommendations (lines 49, 51, 57–58). Next, the patient shares some thoughts about accepting the referral noting that both he and his wife will need a dietician after the baby is born, and he could go first (line 58). This is a notable change from the patient’s response earlier in the visit when the doctor brought up diet. Here, the patient’s response shows acceptance and a stated commitment toward changing the identified health behavior.

All of the teachable moments cases followed this pattern. A wide range of conditions prompted teachable moments (e.g. new onset of diabetes, uncontrolled blood pressure and cholesterol, acute asthma exacerbation, desire to avoid medication, pain in joints, snoring). Both patients and clinicians introduced potentially salient concerns and created links between the salient concern and the health behavior. In addition, teachable moments occurred throughout visits, including during history-taking, diagnosis, and treatment discussions.

As indicated in Table 2 nearly 60% of visits included a salient patient concern that could be linked to a relevant health behavior and 11.2% (n=61) of cases were crafted into a teachable moment. Teachable moments were observed across the majority of physicians: 77% of the physicians who had at least 10 instances of health behavior discussions (n=26) were observed to create at least one teachable moment (mean proportion of discussions per physician =0.09). Other phenomena including missed opportunities (30.8%) and teachable moment attempts (17.2%) were more frequently observed and are discussed next.

Table 2.

Frequency of teachable moments and related health behavior discussion types (n=548 instances of talk)

| Category of health behavior talk | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Teachable moment | 61 (11.1) |

| Teachable moment attempt | 94 (17.2) |

| Missed Opportunity | 169 (30.8) |

| Advice | 57 (10.4) |

| In Action | 132 (24.1) |

| Assessment Only | 35 (6.4) |

3.2 Missed opportunities

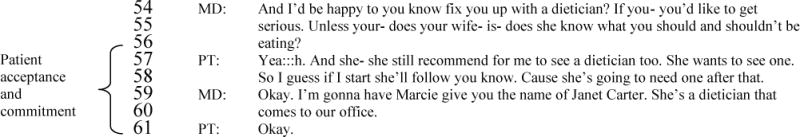

As we show with Case 1, a salient concern with a relevant health behavior component can be leveraged to motivate health behavior change. Missed opportunities are patient visits where a salient concern with a relevant health behavior component was discussed but a link was not made between the salient concern and the health behavior, or a link was made, but there was no attempt to motivate patient behavior change. Case 2 is an example of a missed opportunity for a teachable moment.

Like Case 1, the patient in this visit is worried about dying from a blood clot because a family member recently died from this. The patient raises this topic de novo (line 5) and explicitly states she is worried (lines 19–31) evidence that this concern is salient to her. The patient asks if her high blood pressure could increase her risk of getting a blood clot, and whether someone who is overweight and inactive is at increased risk (lines 8–12). These questions introduce a link between the patient’s weight, inactivity, and risk for blood clots. The physician responds by discussing the risk factors associated with clotting and stating that the patient’s elevated blood pressure does not heighten her risk. This successfully addresses the patient’s concern because in line 33 the patient says “Oh. Okay” and is audibly relieved. This is an example of a missed opportunity because, while the physician addressed the patient’s main concern, the context was ripe to motivate health behavior change. The opportunity to refocus the patient’s worry and acknowledge excess weight and inactivity as important health risks for blood clots and more immediately high blood pressure was missed. Other examples of missed opportunities followed this pattern: presence of a patient concern relevant to an at-risk health behavior where a link between the two is not made and/or there is no attempt on the part of the physician to motivate health behavior change.

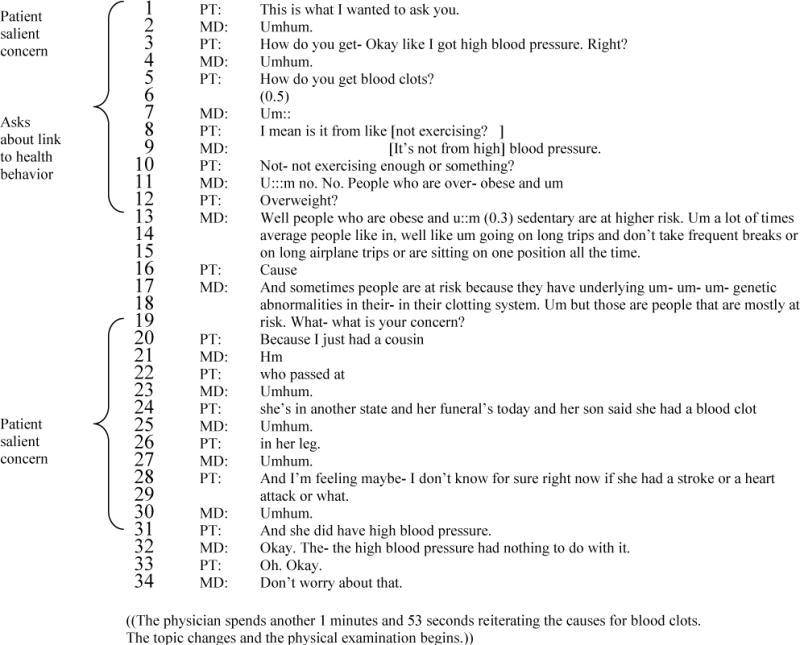

3.3. Teachable moment attempts

Teachable moment attempts share the following two features with teachable moments: the presence of a concern that has a relevant health behavior component, and a link that is made between the health behavior and the patient’s concern that attempts to motivate the patient toward health behavior change. The third component of the teachable moment – the response from the patient that commits to change – is not present. We illustrate two ways the conversation between physicians and patients can result in lack of commitment: 1) patients reject that the health behavior is a problem, and 2) physicians link to concerns that are not salient for patients.

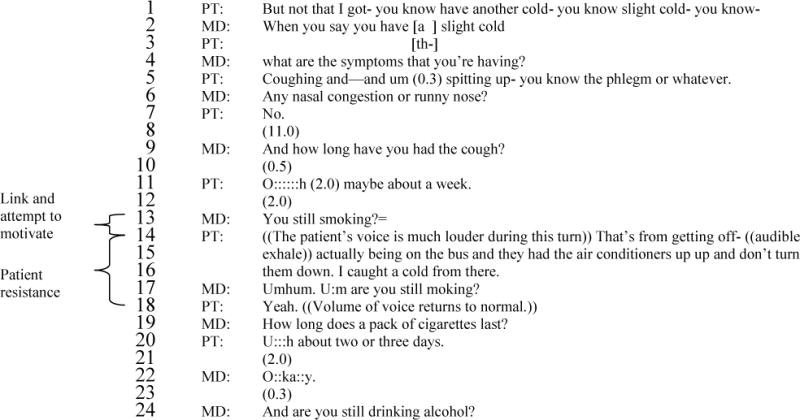

In this visit, that patient’s salient concern is a sore throat. The physician and patient discuss the patient’s symptoms and in this context the physician brings up smoking. The physician’s question in line 13 – “You still smoking?” – indicates the physician knows the patient is a smoker and believes she is continuing this behavior.[40] In addition, given its proximity to the patient’s presenting concern, this question can be heard to make a link between the patient’s smoking behavior and her salient concern – her sore throat.[41] This link is a potential first step in a teachable moment. In response, the patient raises her voice (she is audibly upset) and proposes an alternative explanation for her symptoms; she was exposed to cold air on the public bus and is sick (lines 14–16). It is evident from the patient’s response that she hears this link, is agitated by it and rejects it, consequently resisting the physician’s move toward a teachable moment. Thus, the physician links to a concern that is salient to the patient (sore throat), but the patient challenges the link between her salient concern and her unhealthy behavior. Later in the visit (not shown), the physician tries again and the patient strongly resists this second teachable moment attempt.

A second way teachable moments go awry is when physicians link to concerns that are not salient for patients. Returning to Case 1, the physician’s first attempt at discussing the patient’s diet is resisted by the patient. “How are you doing watching your diet?” (line 1) is a question that shows the physician believes this patient should be watching his diet. In response, the patient states that he is not watching his diet (line 2), and this state of affairs is treated as undesirable (lines 3–6). In lines 11–13, the physician attempts a teachable moment, linking dieting with weight loss and the possibility of reducing medication. The patient’s response (“Well I’m planning on doing that” – line 15) indicates he is not going to do this now and is a form of resistance. As we show above, the physician later attempts to a second teachable moment, this time linking diet to a concern that emerges as clearly salient to the patient: dying. This second attempt is successful. These cases illustrate that more than one teachable moment or teachable moment attempt may be present in a single visit and that linking to a concern that is clearly salient to patients is important.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1 Discussion

This study establishes that teachable moments occur in primary care visits and shows how they are enacted through communication between physician and patient. By recognizing a patient’s salient concern and linking that concern with a relevant health behavior, physicians attempt to motivate patients and, when successful, may elicit patient’s commitment to health behavior change. To do this effectively, physicians need to identify and explore the salience of patient concerns and recognize opportunities to link them with unhealthy behaviors. Physicians do not, however, accomplish teachable moments unilaterally; patient participation is essential. Patients negotiate and are the final judge of the salience of a concern and use a range of strategies to resist attempts to motivate. We observed teachable moments carried out by the majority of physicians in this study. This suggests that the skills necessary for accomplishing teachable moments are well within physicians’ grasp. Moreover, our quantitative findings suggest that while there is additional opportunity for using this technique in health behavior counseling, physicians are making an effort to engage in teachable moments in more than 25% of visits.

A key feature of the teachable moment is the presence of a concern salient to the patient. While it may be common to assume that the salience of a concern is fixed or static, our findings suggest otherwise. Physicians can alleviate as well as escalate patients’ worries, and they can reframe patients’ salient concerns that do not have an obvious health behavior component to be one that does. The plasticity of patients’ salient concerns – that they are open to revision through conversation with physicians – creates the possibility that a broad range of events can be reframed to be salient to patients and motivate health behavior change. Additionally, when physicians attempt to link to a medically relevant concern, but one that is not salient to the patient, efforts to motivate health behavior change can meet with patient resistance. Some forms of resistance are subtle and easy to miss or misunderstand. Motivational interviewing may provide useful techniques for efficiently and effectively managing resistance when it is manifest.[42–44]

An important strength of this study is the number of clinical encounters we studied and that we observed teachable moments as they unfold naturally in the primary care setting. This study would have been further strengthened had we examined video-recordings of medical encounters which offer a more comprehensive understanding of the communication between physician and patient by providing access to eye gaze, body comportment, and facial expression. [45, 46] In addition, we were unable to collect data to examine the characteristics of those patients eligible, but refused participation in the study. While it is unlikely that the communication patterns that we observed would differ among nonparticipants, it is important for future research to replicate this study in other samples of physicians and patients. Other ways to extend this research include exploring how patients and providers perceive and think about teachable moments, teachable moment attempts and missed opportunities (perhaps by coupling observation with post-encounter stimulated recall), and examining if teachable moments lead to actual behavior change rather than relying on patients’ statements of intended action. While some literature suggests that one strong predictor of change is a statement of commitment,[47, 48] what people say they will do when talking to their physician and what people actually do can differ. Thus, evaluating the effect of a teachable moment on actual patient health behavior change is an important next step for research.

4.2. Conclusion

This study extends research on teachable moments by examining this phenomenon in primary care. To date much of the research on teachable moments has been among individuals who have experienced a significant health event.[1, 12, 13] Our work shows that in the primary care setting a broad range of common, everyday health events can be salient concerns and, as such, these events can become teachable moments if they are leveraged to motivate health behavior change. Further, previous research has focused on the emotional and affective aspects of teachable moments,[1, 13] but little was known about how a salient concern develops and becomes a teachable moment.

4.3 Practice implications

This study identifies how the meaning and salience of concerns are transformed into teachable moments through the social interaction between patient and physician during clinical encounters. These findings show how a teachable moment can be accomplished, the prevalence of opportunities for teachable moments and the different ways in which opportunities are missed.

Supplementary Material

Practice Implications.

The skills necessary for accomplishing teachable moments are well within the grasp of primary care physicians.

Case 1.

2003 4450

This is a 40 year-old man in for a routine check of his cholesterol, blood sugars and high blood pressure. The patient reports that he lost 4 pounds since his last visit and the physician congratulates him. The physician asks the patients about his experience with symptoms of diabetes (e.g. thirsty, frequency of urination) and if he is checking his blood sugars. He is not. The physician then reports the patient’s weight at this visit and his prior visit, and the patient notices he lost only 2 pounds. The patient is disappointed. The physician frames the weight loss as positive change and then asks the question, in the transcript, below about his diet.

Case 2.

1601 749

This is a 44 year-old woman seeing the doctor for a chronic routine visit. This patient is obese. After the physician and patient greet each other, the patient brings up her weight, commenting that she didn’t lose any. The physician checks the chart and reports the weight that was recorded today and at the patient’s last visit, reporting that the patient lost fourteen pounds. The topic closes with an exchange of positive remarks about the weight loss, and the patient introduces a new concern as seen below.

Case 3.

1601 671

The patient is a 49 year-old woman seeing the physician for a sore throat. Following a brief greeting, the physician asks the patient about her concerns and the patient reports ‘Something is wrong with my throat.’ This is the patient’s salient concern. The physician asks the patient to describe her symptoms, and the patient describes a sort of pain, indicating that she has had this problem in the past when she had a cold. The physician asks if this problem came back recently, and the patient says it never went away, and now she has another slight cold. This is where the transcript below begins.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant to Susan A. Flocke by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 105292). The authors would like to acknowledge the work by Leslie Cofie and Antje Daub to code the cases. Mary Step, PhD provided helpful comments on a draft of the manuscript. Preliminary findings were presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group November, 2008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments for motivating smoking cessation. Health Education Research Quarterly. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: the power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:320–3. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Making time for tobacco cessation counseling. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:425–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA. Opportunistic preventive services delivery. Are time limitations and patient satisfaction barriers? J Fam Pract. 1998;46:419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosher CE, Lipkus IM, Sloane R, Kraus WE, Snyder DC, Peterson B, Jones LW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Cancer survivors’ health worries and associations with lifestyle practices. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:1105–12. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demark-Wahnefried WL, Jones W. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:319–42. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow RE, Stevens VJ, Vogt TM, Mulloolye JP. Changes in smoking associated with hospitalization: Quit rates, predictive variables, and intervention implications. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1991;6:24–29. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorin AA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Medical triggers are associated with better short-and long-term weight loss outcomes. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory. 2004;39:612–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene J. Forced abstinence and the ‘teachable moment’: hospitalization provides a good opportunity to encourage smokers to quit. Hospitals & Health Networks. 2003;77:30–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: the context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2003;10:325–33. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBride CM, Puleo E, Pollak KI, Clipp EC, Woolford D, Emmons KM. Understanding the role of cancer worry in creating a “teachable moment” for multiple risk factor reduction. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:790–800. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochbaum GM. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Sociopsychological Study. Government Printing office; Washington, DC: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weick KE. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1993;38:628–652. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions. An evidence-based approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stange KC, Zyzanski JS, Jaen CR, Callahan EJ, Kelly RB, Gillanders WR, Shank JC, Chao J, Medalie JH, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, Gilchrist VJ, Langa DM, Goodwin MA. Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. The Journal of Family Practice. 1998;46:377–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine LJ, Philogene GS, Gramling R, Coups EJ, Sinha S. Prevalence of multiple chronic disease risk factors. 2001 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:S18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Isaacson NF, Hung DY, Dickinson LM, Fernald DH, Green LA, Crabtree BF. Practice-level approaches for behavioral counseling and patient health behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etz RS, Cohen DJ, Woolf SH, Holtrop JS, Donahue KE, Isaacson NF, Stange KC, Ferrer RL, Olson AL. Bridging primary care practices and communities to promote healthy behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aspy CB, Mold JW, Thompson DW, Blondell RD, Landers PS, Reilly KE, Wright-Eakers L. Integrating screening and interventions for unhealthy behaviors into primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S373–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holtrop JS, Dosh SA, Torres T, Thum YM. The community health educator referral liaison (CHERL): a primary care practice role for promoting healthy behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S365–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Lee PW, Starr P. Changing adolescent health behaviors: the healthy teens counseling approach. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S359–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Frazier CO, Johnson RE, Rothemich SF, Wilson DB, Devers KJ, Kerns JW. An electronic linkage system for health behavior counseling effect on delivery of the 5A’s. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S350–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green LA, Cifuentes M, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. Redesigning primary care practice to incorporate health behavior change: prescription for health round-2 results. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S347–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin MA. Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics. Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland: 2003. Using Direct Observation in Primary Care Research and the Hawthorne effect. Defining the nature and impact of nurse observers on patients and family physicians interactions; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atlas.ti. Scientific Software Development GMBH. Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garfinkel H. Studies in enthnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heritage J. Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stivers T. Treatment decisions: negotiations between doctors and patients in acute care enounters. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in medical care: Interaction between primary care physicians and patients. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomerantz A, Gill VT, Denvir P. When patients present serious health conditions as unlikely: anaging potentially conflicting issues and contraints. In: Hepburn A, Wiggins S, editors. Discursive research in practiceL New approaches to psychology and interaction. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pomerantz A, Rintel AE. Practices for reporting and responding to test results during medical consultations: Enacting the roles of Paternalism and Independent Expertise. Discourse Studies. 2004;6:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson JD. An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients’ participation. Health Commun. 2003;15:27–57. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson JD, Heritage J. Physicians’ opening questions and patients’ satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heritage J, Robinson JD. The structure of patients’ presenting concerns: physicians’ opening questions. Health Commun. 2006;19:89–102. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heritage J, Sefi S. Dilemmas of advice: aspects of the delivery and reception of advice in interactions between Health Visitors and first-time mothers. In: Drew P, Heritage J, editors. Talk at Work Interaction in Institutional Settings. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 359–417. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pomerantz A, Fehr B. Conversation analysis: An approach to the study of social action as sense making practices. In: Dyke Tv., editor. Discourse: A multidisciplinary Introduction. Sage Publications; London: 1997. pp. 64–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heritage J, Atkinson JM. In: Structures of social action studies in conversation analysis. Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. London: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heritage J, Boyd E. Taking the history: Questioning during comprehensive history-taking. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in medical care. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sorjonen M, Raevaara L, Haakana M, Tammi M, Perakyla A. Lifestyle discussions in medical interviews. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in medical care: Interactions between primary care physicians and patients. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 340–378. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide for Practitioners. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller WR, Rollnick A. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin C. Restarts, pauses and the achievement of a state of mutual gaze at turn beginning. Sociological Inquiry. 1980;50:272–302. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodwin C. Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:862–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64:527–37. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.