Abstract

Objective:

To enquire about the level of awareness regarding various important aspects of palliative medicine among doctors of various departments in four Medical Colleges in Kolkata through a questionnaire.

Materials and Methods:

A questionnaire was developed by few members of Indian Association of Palliative Care. It was distributed, to a convenience sample of doctors who worked at various departments in all four teaching hospitals in Kolkata. The distribution and collection of questionnaires was carried out within four months.

Results:

The results suggested that 85% of the doctors felt that cancer was the commonest reason for the palliative care teams to be involved. Seventy four percent of the doctors mentioned that pain control was their prime job; 53% said that they are enjoying their encounter with palliative care, so far; 77% of the doctors thought breaking bad news is necessary in further decision making process; only 22% of the doctors reported the WHO ladder of pain control sequentially, 35% of the doctors believed other forms of therapies are useful in relieving pain, 35% of the doctors thought that they gave enough importance and time for pain control; 77% said that they had heard about a hospice, among them still 61% of the doctors thought that the patients should spend last days of their life at home. Thinking of the future, 92% of the doctors think that more and more people will need palliative care in the coming days.

Conclusion:

Amongst the doctors of various departments, there is a lack of training and awareness in palliative care. Almost all the doctors are interested and they are willing to have more training in pain control, breaking bad news, communication skills and terminal care.

Keywords: Awareness, doctors, palliative medicine

INTRODUCTION

Palliative medicine is one of the developing medical specialities. It has been recognized by World Health Organization (WHO) and defined as an approach which improves the quality of life of the patients and their families facing life-threatening illness through prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems as physical, psychosocial and spiritual.[1] In United Kingdom, General Medical Council have held doctors guilty of serious professional misconduct because they have been unable to provide palliative medicine or refer for specialist palliative medicine.[2] The concept of palliative medicine is not new. In 460 BC, Hippocrates became the father of medicine by providing simple symptom relief. In the modern world, many developed countries do not consider cancer services provision appropriate until the services have the back up of palliative medicine teams.[3] Many developing countries do recognize the need for palliative medicine. India is running well-designed teaching programs with the establishment of Indian Association of Palliative Care.[4] This article reports on the results of a survey undertaken to enquire about the level of awareness regarding various aspects of palliative care among doctors working in various departments in all four Medical Colleges in Kolkata through a questionnaire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

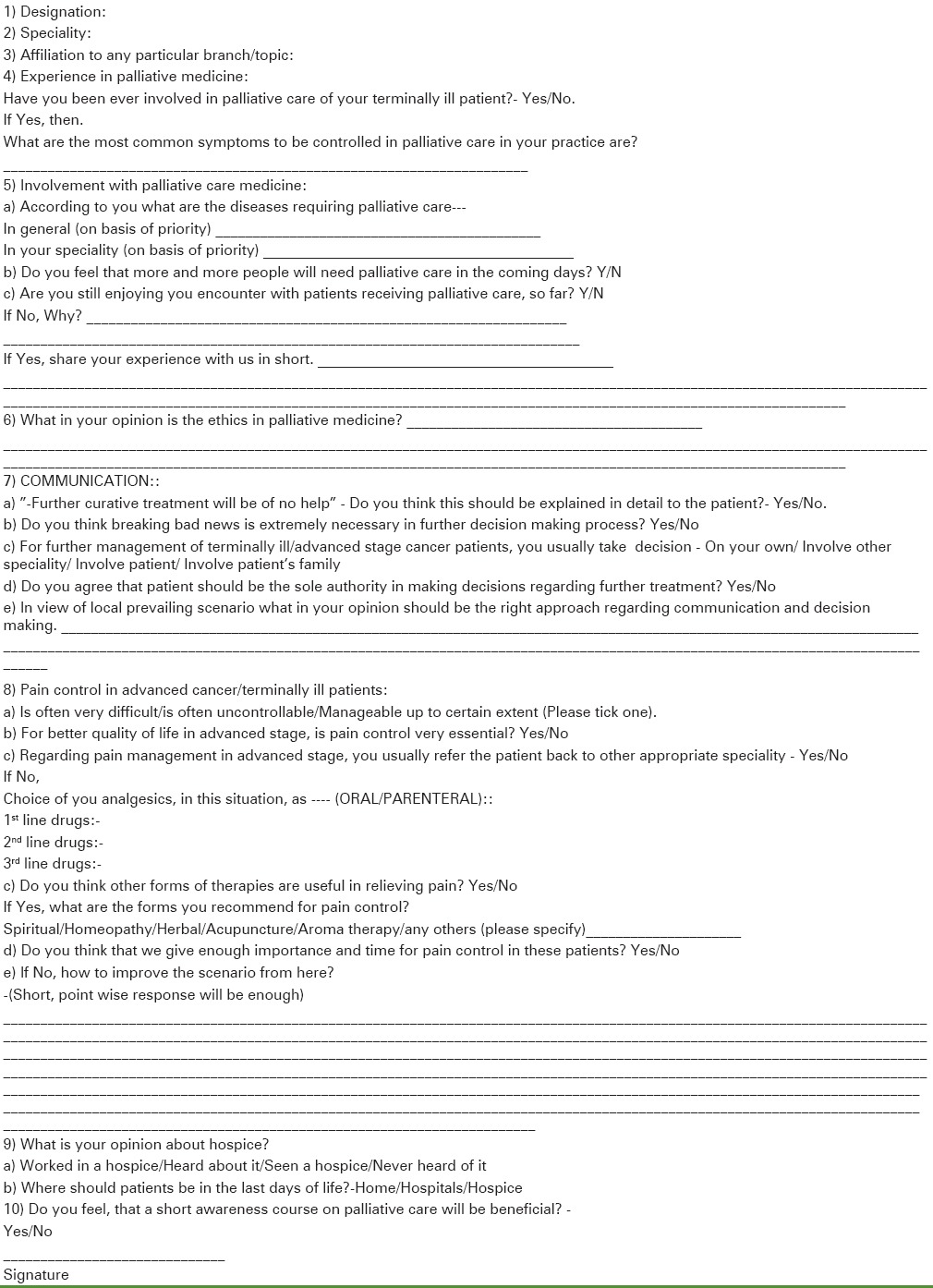

A questionnaire [Table 1] was developed by few members of Indian Association of Palliative Care in Medical College, Kolkata. Ethical committee clearance was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee Board. The questionnaire was internally validated by a pilot study done in Department of Radiotherapy, Medical College, later another bigger sample evaluation from three departments i.e., General Medicine, Surgery and Gynecology was done and correlated among the groups of questions. It was distributed, by hand and via mail, to a convenience sample of doctors who worked at various departments in four teaching hospitals in Kolkata. The distribution and collection of questionnaires was carried out within four months. The questionnaire approach was used to reach a wider number of responses in a relatively short time and at lower cost.

Table 1.

Feedback for palliative care concern and awareness

RESULTS

Of the 688 questionnaires sent, 648 (>93%) were returned. The respondents had a background of a variety of specialities, with 144/648 (22.2%) doctors working in general medicine, whereas 328/648 (50.6%) worked in surgical and allied fields e.g. ENT, anesthesia and 176/648 (27.1%) worked in gynecology and obstetrics.

One hundred forty-four (22.2%) doctors were working as assistant professor or at Senior level. Most doctors i.e., 488 (75.6%) were experienced or were involved in palliative care some way or the other.

After the demographic details, they were asked questions about:

The reasons for providing palliative medicine (diseases and aims)

Their experience of palliative medicine

Ethical issues about palliative medicine

Pain control

Issues around terminal care (Hospice etc.).

The diseases, for which doctors felt palliative medicine was important, ranged enormously. In total, they named 11 diseases as first priority, 13 as second priority. The most frequently mentioned diseases requiring palliative medicine, in any priority order, to be mentioned was cancer (552-85.2%), stroke (48-7.4%) and neurodegenerative disease (24-3.7%).

Four hundred eighty doctors (74.0%) mentioned about pain control as the primary aim for palliative care management. When they were asked whether they were enjoying their experience with palliative medicine, 300 doctors (53.0%) stated that they were enjoying their experience, while 252 doctors (38.8%) were not happy with their experiences, rest did not answer to this question. When asked about the future of palliative medicine. 588 doctors (92%) thought that more and more people will be in need of palliative medicine in future.

When asked whether breaking bad news to the patient is necessary, 504 doctors (77%) thought it was absolutely necessary. When asked whether they explained the prognosis of the disease in detail to the patient, 540 doctors (73%) said they explained in details and fully to the patients.

Regarding decision making, only a few of them (60-9.2%) said they took decision on their own while a majority (564- 87%) said they took decision in consultation with other specialities. Involving the patient too, in decision making was done by 240 doctors (37%) while involvement of family in decision making was sought out by 576 doctors (70%). When it came to the question that whether patient was the sole authority for decision making, majority of them 480 doctors (56%) replied negative.

When asked about the choice and sequence of the analgesia, in terminal cancer pain, correct sequence following WHO ladder of pain control only 22% stated the correct sequence of drugs, although a variety of other forms of pain control was also used by many of them.

The doctors were also asked whether they felt comfortable with any other form of treatment other than allopathic. Four hundred and eight (62.9%) doctors stated that they had no objection. The treatment mentioned by the doctors were spiritual (n = 168, 25.9%), aroma therapy (n = 36, 5.55%), acupuncture (n = 180, 27.7%). Other forms of therapy mentioned were yoga, physiotherapy etc.

Lastly, the doctors’ knowledge about the hospices was questioned. Five hundred and four doctors (77.0%) stated that they had heard about a hospice, although none had seen one and 84 of them (13%) had never heard about a hospice. When asked about the preferred place of providing terminal care, 384 doctors (59%) mentioned home and 168 doctors (25%) chose hospice.

Statistical tests on the data were not performed as the questions asked were open-ended with answers given on individual discretion.

DISCUSSION

Palliative medicine is now perceived as an integral part of medical care rather than ‘elite medicine’. Like any other sub-speciality, palliative medicine training is an essential part of the general internal medicine. As the methods to relieve intractable symptoms and patients’ distress are increasing day by day, it will be inappropriate to expect all the doctors to be able to provide specialist palliative medicine services. However, it remains a generalist's, either primary care doctor or general physician/surgeon, responsibility to start palliative management.

In first part of the questionnaire, the doctors were asked about their perception of palliative medicine and its uses. World Health Organization defined palliative medicine for the first time in 1990, as ‘a facet of oncology, concerned with the control of symptoms rather than with the control of the disease’.[5] The approach now, as designed by WHO, is to consider all the incurable, life-threatening diseases, but cancer remains the top reason for the referrals.

Other diseases mentioned by the sample doctors like stroke or old age are certainly not the cases for specialist palliative medicine. Other diseases for referral to specialist palliative medicine teams are incurable neurological diseases e.g., multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and incurable infective diseases e.g., AIDS, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis etc., The findings of this survey indicate that the doctors need to be more aware of the disease trajectory of palliative medicine.

In the questionnaires, although a guide was written to identify the aims of palliative medicine team, a slot was left to write about what doctors felt was the main aim. The doctors mentioned pain control, counselling and rehabilitation as the main aims. A study in UK had indicated that these are the same aims identified by the general population in UK.[6] Interestingly, the aim identified by the doctors themselves has been ‘Quality of life as primary focus of palliative medicine’. It is worth stressing that the quality of life should be subjective and multidimensional, dynamic, time-specific and is not defined by functional ability, performance status or cognition.[7] The findings of the survey indicate that the doctors are aware of the remit of palliative medicine.

The results of the answers about the experience of palliative medicine and breaking bad news were interesting. Seventy three percent of the doctors felt that they convey and explain in details the bad news to the patients. Studies have shown that 49% consultants have no formal training in breaking bad news and generally 70% of consultants felt that breaking bad news was inadequately done in the hospitals across UK.[8] Furthermore, there are no formal studies of any protocol to suggest any one way is better than the other.[9]

According to our questionnaire, 70% of the doctors mentioned that not infrequently, they involve the families and not only the patients in decision making. It is a well-established concept that a mentally competent patient has the right to knowledge. It is an ethical and legal requirement in many countries.[10] One can argue that in western world, where individualistic attitudes are common, this principle is valid whereas in countries like India, families are entitled in Sharing of information. It is a perfectly reasonable argument and should be followed in good practice. However, the doctors should not deprive patients of the truth. There is considerable evidence that patients who are aware of their conditions accept the treatment and consequences better and also have improved quality of life.[11] There is sometimes the fear that the patients would ‘give up’ after they are told about the diagnosis of a terminal illness. However studies suggest that usually these fears are unfounded and can cause more damage than harm. Also that there are models which can help to provide quality of life after being told of terminal nature of disease.[12] It has been identified by healthcare professionals around the world and governing bodies like WHO, that families should be recognized as experts in gathering information about specific behavior that helps in patients’ care (e.g., patients’ like and dislikes, fears, concerns and beliefs etc.).[13] Also, it is recognized that by sharing the information, the doctors can create a good relationship with patients and families, which leads to smooth transition of events of continuing and terminal care. It must also be said that although more than 27% of the doctors felt disturbed or disappointed, it must be realized that death is the only sure event in our lives. Dying is not a failure. It is dying with loss of dignity and in distressing symptoms, which is deemed unacceptable.[14] The findings of this survey indicate that the doctors are confident about their understanding of breaking bad news and importance of involving both the patient and his/her family in decision making. Further data is required to explore their techniques and patients’ experiences of doctors’ expertise.

Regarding the pain control in cancer patients, World Health Organization guidelines for managing cancer pain refer to a ladder pattern. At first step, it advises to administer non-opioids (e.g., Paracetamol), if necessary in addition of an adjuvant drug (e.g., NSAID). Second step asks for adding moderate opioids (e.g., Codeine, Tramadol etc.) and third step advises to administer strong opioids (e.g., Morphine-Gold standard).[15] In many parts of India morphine is usually difficult to obtain, there are different other strong opioids e.g., Buprenorphine, Pentazocine, Fentanyl etc., However, lateral thinking has helped to overcome it. Lack of knowledge about the cancer pain is sometimes due to more stress on curative treatment and failure to accept the terminal nature of the illness.[16] Also, direct lack of education has been attributed as the most prevalent cause of inadequacy of cancer pain control.[17,18] Although, in our survey doctors identified various appropriate drugs, very few of them sequenced the WHO ladder correctly, which implies that there is a need to explain this most important protocol. This approach has been tested and proven valuable in many studies. In one of the studies, out of 156 patients, 87% ultimately became pain free using this ladder analgesic pattern.[19] There was a fair amount of thought in our survey about the complementary medicine. There is no evidence that any complementary medicine can help curative treatment, but techniques like aromatherapy, music therapy, acupuncture, relaxation therapy etc., have been helpful in managing the patients’ suffering and mental distress.[20] In eastern world in general, the religious coping mechanisms are well established source of strength and well being.[21] This mechanism is also supported in the bereavement phase. In the west, the bereavement support is provided by trained counsellors but in east, extended families play an important role. The findings of this survey indicates that majority of the doctors respect the patients’ right to complementary medicine.

Although more than 77% of the doctors had heard about/seen/worked in a hospice, only 25% mentioned that hospice would be their patients’ preferred place for dying. In fact, 53% mentioned that they would prefer home. This figure is very much culturally dependant. In Belgium, which is a Western European country, with lot of emphasis on individualism, data suggests that only 16% of the patients die at home, whereas 76% die in hospital/nursing home.[22] In contrast to that, data from Italy, which is a Mediterranean country with strong family values, shows that 86% of patients die at home and only 14% in hospital and nursing homes.[23] Wide availability of palliative medicine services should enable the patients to die at home, with their loved ones. Hospitals have been felt too intrusive or busy at times to deal with the dying patients. The findings of this survey indicate that doctors are conscious of the patients’ needs while making decisions about the venue of the patients’ last days.

The most promising aspect of this study was that all of participating doctors felt that a short course on palliative care workshop would be beneficial indicating the urge to know and participate more and more in this arena.

Besides, there are some limitation of this study, the study being conducted among doctors of medical colleges in a city, the number of sampling doctors were less. Besides, the doctors practising in rural areas should be taken into account as they are also involved in providing palliative care to the patients at home who might not enjoy the benefits of a metropolitan city. The study should be broadened to include as much as possible of the doctors of our nation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: WHO; 2002. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley J. The General Medical Council and the right to specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 1997;11:317–18. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.London: National Health Services; 2000. Manual of Cancer Services Standard. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sureshkumar K, Rajgopal M. Palliative care in Kerala. Palliat Med. 1996;10:293–8. doi: 10.1177/026921639601000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders C. London: Edward Arnold; 1984. Appropriate treatment, appropriate death: The management of terminal malignant disease. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarrett N, Payne S, Turner P, Hillier R. Someone to talk to and pain control. What people expect from a specialist palliative care team. Palliat Med. 1999;13:139–44. doi: 10.1191/026921699669165706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldron D, O’Boyle CA, Kearney M, Moriarty M, Carney D. Quality of life measurement in advanced cancer: Assessing the individual. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3603–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett M. Netherlands: The Hague; 2003. Apr 3rd, Lecture at 8th Congress of European Association of Palliative care. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waitzkin H, Stoeckle JD. The communication of information about illness. Clinical, sociological, and methodological considerations. Adv Psychosom Med. 1987;8:180–215. doi: 10.1159/000393131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckman R. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press; 1999. Communication in palliative care: A practical guide. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisman A. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1979. Coping with cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penson J. A hope is not a promise: Fostering hope within palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2000;6:94. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2000.6.2.8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson-Barnett J, Richardson A. London: Oxford University Press; 1999. Nursing research; pp. 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sykes NP, Pearson SE, Chell S. Quality of care of the terminally ill: The carers’ perspective. Palliative. 1992;6:227–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geneva: WHO; 1986. World Health Organisation. Cancer pain relief. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwyer L. Palliative medicine in India. Palliat Med. 1997;11:487–8. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larue F, Colleau SM, Fontaine A, Brasseur L. Oncologists and primary care physicians’ attitudes towards pain control and morphine prescribing in France. Cancer. 1995;76:2375–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2375::aid-cncr2820761129>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zenz M, Zenz T, Tryba M, Strumpf M. Severe undertreatment of cancer pain: A 3 year survey of the German situation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:187–91. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda F. Results if filed-testing in Japan of the WHO draft interim guidelines on the relief of cancer pain. Pain Clin. 1986;1:83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishman B. The treatment of suffering in patients with cancer pain. In: Foley K, Bonica J, Ventafridda V, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy. Vol. 16. New York: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 301–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spilka B, Spangler JD, Nelson CB. Spiritual support in life-threatening illness. J Relig Health. 1983;22:98–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02296390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrijvers D, Joosens E, Middelheim AZ, Verhoeven A. The place of death of cancer patients in Antwerp. Palliat Med. 1998;12:133–4. doi: 10.1191/026921698677498024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Conno F, Caraceni A, Groff L, Brunelli C, Donati I, Tamburini M, et al. Effect of home care on the place of death of advanced cancer patients. Euro J Cancer. 1996;32A:1142–7. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]