Abstract

Aims:

To asses self-reported sleep disturbance and its associated factors in 50-60-year-old Menopause women.

Settings and Design:

This cross sectional study included 700 healthy 50-60-year-old women volunteers who were postmenopausal for at least 1 year. The volunteers were interviewed after providing informed consent. The study questioner included two main aspects: Personal characteristics and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Data were analyzed by using SPSS 14 software.

Results:

The mean sleep scale score was 7.84 ± 4.4. Significant correlations had seen between sleep disturbance and characteristics of occupational status, educational status, husband's occupational status, and economical status, and (P = 0.002). There were no significant correlation between sleep disturbance and other personal characteristics, such as age; partner's age; number of children; family size; consumption of tea, coffee, or cola.

Conclusions:

Sleep disturbance is common in menopausal women. Taking into account the sleep-related personal characteristics, suitable interventions should be taken to improve sleep quality, which is a very important for maintaining the quality of life.

Keywords: Menopause, related factors, sleep quality

INTRODUCTION

For many women, the onset of Menopause and symptoms associated with hormonal changes and cessation of ovulation can affect quality of life and perceptions of health and well-being. This in turn, can impact upon cultural and economic issues.[1] Estrogen decline during menopause may cause various problems such as vasomotor instability, lowered psychometric functions, vaginal and urinary infections, and forgetfulness.[2] The other symptoms include irregular menses, decreased fertility, vaginal dryness,[3] hot flashes, sleep disturbances,[3,4] mood swings, increased abdominal fat, hair thinning, and loss of breast fullness.[3]

Sleep is an essential aspect of life,[5] and insomnia is associated with negative health consequences including fatigue, impaired daytime function, reduced quality of life, and increased visits to health care providers.[2,6] Sleep disturbance is one of the important symptoms observed during menopause too[7] also common and clinically important among elderly individuals.[4,8,9]

Approximately one-third of the adult population reports symptoms of insomnia.[10] Women tend to report sleep disturbances more often than do men of the same age[11] further, insomnia is more common in patients with chronic medical problems and is observed in up to 69% of patients enrolled in primary care clinics.[12] Moreover, after menopause, the prevalence of habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome also increases in women.[13] In contrast, a smaller percentage of adults report severe sleep problems (10%-15%), but the prevalence of severe chronic sleep problems increases to 25% among the elderly.[14] Kravitz (2003) reported that the rates of self-reported sleep difficulties increase during the menopausal transition.[15] Further, the overall prevalence of self-reported sleep difficulty was 38%, and in some studies, it was found to be the least prevalent in the premenopausal group (31%) and most prevalent in the surgical menopausal group (48%).[16] Referring to study in West of Tehran (2011) its rate in healthy menopause women was 70%.[4]

Numerous national surveys have shown that approximately 30%-40% of adults experience sleep disturbances.[17,18] Also referring to study, which had done in west of Tehran (2011) 70% of healthy menopause women experiences insomnia.[4]

The main findings of a study by Young et al., (2003) indicated that objectively measured sleep quality does not diminish with menopause, but the association of menopause with sleep quality differs with respect to objective and subjective measures. These findings indicated that menopausal women were more dissatisfied with the quality of sleep than were premenopausal women.[19] Various factors such as snoring, aging, hot flashes, and night sweats could influence the quality of sleep during menopause.[1]

Based on the results of the aforementioned studies and due to the fact that sleep disturbance is one of the important symptoms observed during menopause and aging, this study was conducted to determine rate of self-reported sleep disturbance in west of Tehran and its associated factors in 50-60-year-old women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study conducted at four selected clinics of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in west of Tehran, during March 2010 to June 2012. This study is the first phase of a research proposal entitled “The effect of valerian and lemon balm on the sleep quality in menopausal women: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial.” In this phase, we were trying to screen menopause women to find those with sleep problems, for entering volunteers to the second phase of mentioned study. The inclusion criteria were as follows:[1] generally healthy women between 50-60 years of age, postmenopausal for at least 1 year, and not undergoing hormone replacement therapy;[2] absence of a medical or psychiatric condition that could cause sleep disturbance;[3] and having scores of 5 or more by using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The volunteers included 700 healthy Menopause women, who were informed about the research and its purposes. Volunteers who were undergoing hormone replacement therapy and/or indulged in tobacco, drugs, or alcohol consumption at the time of the study were excluded. Thus, 700 volunteers were finally included in this study, and were requested to complete a questionnaire regarding their personal characteristics and PSQI.

The aim of the study was explained to the entire 700 volunteers, whom had qualified for the first phase of study filed in provided written informed consent, then interviewed by using a questionnaire, which had three main sections of personal characteristics, perception towards sexual satisfaction and PSQI. The section on personal characteristics included the following 15 items: Age; partner's age; date of last menstruation; family size; number of children; number of children living with the volunteers; educational status; economic status; marital status; occupational status; partner's occupational status; average rate of daily consumption of tea, coffee, and colas. Referring to their perception of sexual satisfaction the visual analog scale (VAS, scale ranging from 0-10) was used. The PSQI section was a self-rated questionnaire that assessed sleep quality and disturbances over 1 month period. The questionnaire had 19 items that were used to generate 7 composite scores. The composite scores provided information about subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction. The scores from the seven components were then summed to yield a single PSQI score. When this single global PSQI score is greater than 5, it is nearly 90% sensitive and specific with regard to diagnosing “poor” sleep. The post hoc cut-off score of 5 on the PSQI produced a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% of patients versus control subjects.

The sample size was calculated based on 80% power and 5% type 1 error and it was determined that 700 subjects were needed for the study. Therefore, we delivered the PSQI questionnaire to 700 volunteers who met the inclusion criteria.

Data were analyzed by using SPSS 14 software. Descriptive statistics, including measures of mean and variance, were calculated for each volunteer's main outcomes. To determine the correlation between the variables and sleep quality, inferential statistics such as Pearson's test, t-test, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Science (TUMS), the oldest and largest Medical Science University of Iran. The members of the Ethics Committee follow the progression of the research from the first step of designing the research proposal to the presentation of the final report.

RESULTS

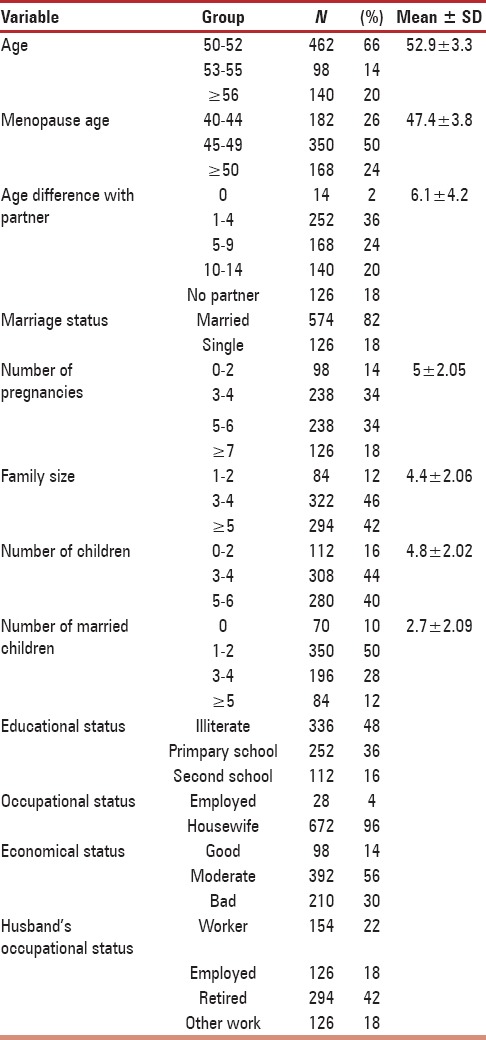

The demographic data obtained from the questionnaire are shown in Table 1. The average age was 52.9 ± 3.3 years, average menopause age was 47.4 ± 3.8 years, average duration of menopause was 5.5 ± 4.4 years, average family size was 4.4 ± 2.06 members, average number of children was 4.8 ± 2.02, and average number of married children was 2.7 ± 2.09. All volunteers drank tea daily, and only 5% did not drink coffee and colas. The highest daily tea consumption was more than four cups per day (32.2% of the volunteers), and the highest daily coffee consumption was 71.4%.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

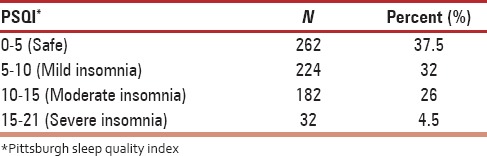

Regarding to PSQI, which assesses sleep quality and sleep disturbances over one month period, the frequency of sleep disturbance was found to be 70% [Table 3].

Table 3.

Sleep quality and frequency of sleep disturbance using PSQI

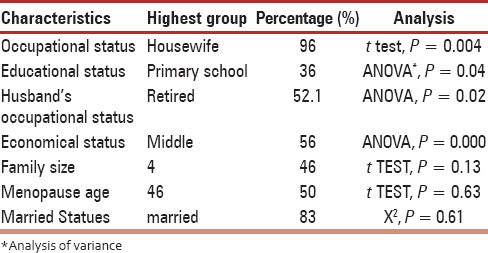

Significant correlations with sleep disturbance just were observed for four characteristics of occupational status, educational status, husband's occupational status, and economical status [Table 2]. Sleep disturbance was not significantly correlated with age; menopause age; age of partner; number of children; family size; and consumption of tea, coffee, and cola.

Table 2.

Analyze of personal characteristics and the pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

DISCUSSION

This study investigated correlations between personal characteristics and self-reported sleep disturbance in 50-60-year-old menopausal women.

Poor sleep quality is highly prevalent in menopausal women.[7,20] The most important intervention factor for decrease in sleep quality in menopausal women is reduction in hormone levels. Age is not the only factor associated with difficulty in sleeping.[16] Moreover, the unique hormonal and psychological changes that occur in middle-aged women at the time of menopause have a significant effect on sleep disturbance.[13] In this study, it was found that age and sleep quality are not correlated. This may be because all the volunteers were postmenopausal with ages ranging from 50-60 years.

In this study, sleep quality and the occupational status (highest group were housewife) were found to be correlated. Furthermore, a correlation was identified between sleep quality and the husband's occupational status, which may be because of lower economical statuses, may have poor access to medical care or having more family distress.

Ohayon et al., (2005) reported that a high degree of education is associated with sleep difficulty[16] and Leshner et al., (2005) determined, that being less educated is associated with a higher prevalence of insomnia.[21] Habte-Gabr et al., (1991) reported that individuals with lower educational statuses may have poor access to optimal medical care and have lifestyles that may result in an overall poor health status.[22] This is expected to increase the risk of sleep disturbances.[8] We found a correlation between educational statuses and sleep quality, and our results were similar to those of the aforementioned studies.

Leshner et al., (2005) indicated that lower income levels are associated with a higher prevalence of insomnia.[21] In this study, economic status and sleep quality were found to be correlated.

The personal characteristics with the highest significant correlation with sleep are economic status, occupational status, husband's occupational status, and educational status. One limitation of this study is the low number of participants. We recommend that more volunteers be recruited for subsequent studies.

CONCLUSION

Our study population included 700 postmenopausal women. It would be helpful to conduct another study with higher number of menopausal women in all districts in Tehran for finding sleep disturbance prevalence. Also conduct other study with andropausal men too. Since the highest groups of menopause was housewife and there was correlation between occupational status and sleep disturbance, it is necessary to do another research for finding its reason, also need to provide more educational and consultation for this high-risk group. The medical staff should be made aware of the personal characteristics of menopausal women, completion of the reproductive period and the commencement of menopause, and importance of sleep quality. Proper planning to execute appropriate guidelines, along with counselling of qualified professionals in supervisory roles is also advisable. This approach could help menopausal women prevent psychological and social damage caused by sleep disturbance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is the first phase of a randomized clinical trial study entitled “The effect of valerian and lemon balm on the quality of sleep in menopausal women: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial,” which is supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research, at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: 11933). This study has been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials Sciences (Code: IRCT201106302172N10). We are very grateful to the participants of this study for making this research possible.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Tehran University of Medical Siences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geller SE, Studee L. Contemporary alternatives to plant estrogens for menopause. Maruritas. 2006;55:S3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and aging: Prevalence of disturbed sleep and treatment considerations in older adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.myoclinic.com, menopause. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menopause/basics/symptoms/con-20019726 .

- 4.Taavoni S, Ekbatani N, Kashaniyan M, Haghani H. Effect of valerian on sleep quality in postmenopausal women: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Menopause. 2011;18:951–5. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31820e9acf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gooneratne NS. Complementary and alternative medicine for sleep disturbances in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:121–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke JR, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:1077–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taibi DM, Vitiello MV, Barsness S, Elmer GW, Anderson GD, Landis CA. A randomized clinical trial of valerian fails to improve self-reported, polysomnographic, and actigraphic sleep in older women with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2009;10:319–28. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habte-Gabr E, Wallace RB, Colsher PL, Hulbert JR, White LR, Smith IM. Sleep patterns in rural elders: Demographic, health, and psychobehavioral correlates. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90195-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mousavi F, Tavabi A, Iran-Pour E, Tabatabaei R, Golestan B. Prevalence and associated factors of insomnia syndrome in the elderly residing in Kahrizak nursing home, Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:96–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 2000;23:243–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National sleep foundation: Women and sleep poll. 1998. [Last accessed on 2006 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www. Sleep foundation.org/sleeplibrary .

- 12.Shochat T, Umphress J, Israel AG, Ancoli-Israel S. Insomnia in primary care patients. Sleep. 1999;22:S359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guilleminault C, Quera-Salva MA, Partinen M, Jamieson A. Women and the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1988;93:104–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bent S, Padula A, Moore D, Patterson M, Mehling W. Valerian for sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119:1005–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Meyer PM. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: A community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohayon MM, Vecchierini MF. Normative sleep data, cognitive function and daily living activities in older adults in the community. Sleep. 2005;28:981–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Li F, Lin Y, Sheng Q, Yu X, Zhang X. Subjective sleep quality in perimenopausa l women and its related Factors. J Nanjing Med Univ. 2007;21:116–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, Austin D, Laurel F. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 2003;26:667–72. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: An epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults, June 13-15, 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shojaeizadeh D, Gashtaee M. Assessing the relationship between knowledge, attitude and healthy behaviour among menopaused women in Tehran in 2000. Iran J Public Health. 2002;31:19–20. [Google Scholar]