Abstract

Objective

This study aims to describe the correlation between age and occurrence of atrial fibrillation after aortic stenosis surgery in the elderly as well as evaluate the influence of atrial fibrillation on the incidence of strokes, hospital length of stay, and hospital mortality.

Methods

Cross-sectional retrospective study of > 70 year-old patients who underwent isolated aortic valve replacement.

Results

348 patients were included in the study (mean age 76.8±4.6 years). Overall, post-operative atrial fibrillation was 32.8% (n=114), but it was higher in patients aged 80 years and older (42.9% versus 28.8% in patients aged 70-79 years, P=0.017). There was borderline significance for linear correlation between age and atrial fibrillation (P=0.055). Intensive Care Unit and hospital lengths of stay were significantly increased in atrial fibrillation (P<0.001), but there was no increase in mortality or stroke associated with atrial fibrillation.

Conclusion

Post-operative atrial fibrillation incidence in aortic valve replacement is high and correlates with age in patients aged 70 years and older and significantly more pronounced in patients aged 80 years. There was increased length of stay at Intensive Care Unit and hospital, but there was no increase in mortality or stroke. These data are important for planning prophylaxis and early treatment for this subgroup.

Keywords: Aged, Atrial Fibrillation, Aortic Valve Stenosis, Postoperative Period

Abstract

Objetivo

Descrever, em idosos, a correlação entre faixa etária e ocorrência de fibrilação atrial após cirurgia por estenose aórtica, além de avaliar a influência da ocorrência de fibrilação atrial na incidência de acidente vascular cerebral, tempo de internação e mortalidade hospitalar.

Métodos

Estudo transversal retrospectivo incluindo pacientes com idade > 70 anos submetidos à cirurgia de troca valvar aórtica isolada.

Resultados

Foram estudados 348 pacientes com idade média de 76,8±4,6 anos. A incidência de fibrilação atrial no pós-operatório foi 32,8% (n=114), sendo superior nos pacientes > 80 anos (42,9 vs. 28,8% 70-79 anos, P=0,017) e havendo significância estatística limítrofe (P=0,055) para tendência linear na correlação idade e incidência de fibrilação atrial. Verificou-se significativo maior tempo de internação na Unidade de Terapia Intensiva e hospitalar total, porém, não se observou maior taxa de acidente vascular cerebral ou de mortalidade hospitalar decorrente da fibrilação atrial.

Conclusão

A incidência de fibrilação atrial no pós-operatório de cirurgia para estenose valvar aórtica em pacientes idosos com > 70 anos foi elevada e linearmente correlacionada ao avanço da idade, especialmente após 80 anos, causando aumento dos tempos de internação total e em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva, sem aumento significativo da morbimortalidade. O conhecimento desses dados é importante para evidenciar a necessidade de medidas profiláticas e de tratamento precoce dessa arritmia nesse subgrupo.

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common complication after cardiac surgery [1] and is associated with higher risks of cerebrovascular accident (CVA), hospital expenses and mortality as well as longer hospital and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stay [2]. In most cases, it spontaneously reverts to sinus rhythm, without the need for pharmacological intervention [3].

Postoperative AF occurs in approximately 30% to 40% of patients who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and in up to about 60% of patients who undergo concomitant valve surgery [4]. The incidence of this arrhythmia depends on the definitions adopted, the characteristics of the patients, the type of surgery performed, and the monitoring method [5]. AF incidence has been increasing for the past few decades thanks to the higher percentage of elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery [1].

This arrhythmia occurs typically on the second or third postoperative day, with 70% of the events occurring by the fourth day. However, it can happen at any time after surgery, including after hospital discharge. In fact, AF is the leading cause of early hospital readmission after cardiac surgery [6].

Indications for aortic valve surgery have been increasing due to an increase in population longevity. Even though AF is expected to be more frequent, there are few data on the prevalence of this condition in individuals aged 80 years or older and on its correlation to morbidity and mortality to offer guidance on the possible need for more aggressive prophylaxis during the preoperative period of more elderly patients.

The aim of this study was to analyze a sample of elderly patients and describe the correlation between age and occurrence of acute postoperative AF after aortic valve stenosis surgery. Secondly, it set out to assess the influence of AF in the incidence of postoperative CVA, hospital length of stay, and hospital mortality.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional retrospective study of patients aged 70 years and older who underwent isolated aortic valve replacement, from 2000 to 2011, due to aortic stenosis or double aortic lesion with predominant stenosis, including reoperations. Patients who underwent associated surgical procedures, including aortoplasty or aortic annular enlargement, and patients with preoperative endocarditis or AF were excluded.

Heart rate was assessed by continuous cardiac monitoring in all patients for a minimum of 72 hours (postoperative ICU) and by daily electrocardiographic examinations until hospital discharge. Additional electrocardiograms were performed when patients suffered palpitations, tachycardia or angina. For the purposes of this study, AF consisted of any episode of supraventricular arrhythmia whose electrocardiography tracing showed "f" waves with varying morphology and amplitude as well as irregular ventricular rhythm.

Angina and heart failure (HF) were classified according to the criteria established by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) and New York Heart Association (NYHA), respectively. Current smoking was defined as smoking one or more cigarettes a day in the past month. Occurrence of CVA was determined in the presence of focal neurological signs or alterations in level of consciousness for > 24 hours. Hospital mortality was defined as death during hospital stay, regardless of length of stay.

Data were collected directly from patients' medical records, then inserted and analyzed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 21.0 software. Descriptive analysis was done through absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables and through average/median and standard deviation/interquartile range for quantitative variables. Comparison of groups was assessed by Student's t-test for normally distributed quantitative variables, by Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables not normally distributed, and by Chi-square test for categorical variables. For low frequencies, Fisher's exact test was used. Multivariate analysis was performed by using multiple logistic regression, where the variables included were the ones with P<0.20 in the univariate analysis. For multivariate analysis of not normally distributed continuous variables, logarithmic transformation was carried out, followed by multiple linear regression analysis with the aforementioned inclusion criteria. The relationship between age and incidence of acute postoperative AF was assessed by chi-square test for linear trends after assigning patients to 5-year age groups. A significance level of 5% was adopted for every test performed. This is a subanalysis of a previous study [7], submitted to and approved by the IC/FUC Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

The sample was comprised of 348 patients, who fit the inclusion criteria established for the study. Demographic characteristics of the studied population are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the studied population.

| Variável | Total | 70-79 anos | ≥ 80 anos | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=348) | (n=250) | (n=98) | ||

| Average age (years) | 76.8±4.6 | 74.5±2.8 | 82.7±2.7 | <0.001 |

| Male patients (%) | 195 (56.0) | 143 (57.2) | 52 (53.1) | 0.562 |

| SAH (%) | 251 (72.1) | 178 (71.2) | 73 (74.5) | 0.629 |

| Diabetes (%) | 77 (22.2) | 57 (22.8) | 20 (20.4) | 0.734 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (%) | 62 (17.8) | 42 (16.8) | 20 (20.4) | 0.525 |

| COPD (%) | 38 (10.9) | 33 (13.2) | 5 (5.1) | 0.047 |

| Previous smoking (%) | 147 (42.2) | 118 (47.2) | 29 (29.6) | 0.004 |

| Current smoking (%) | 10 (2.9) | 9 (3.6) | 1 (1.0) | 0.293 |

| Heart failure III/IV (%) | 132 (37.9) | 91 (36.4) | 41 (41.8) | 0.414 |

| LVEF < 40% (%) | 28 (8.0) | 16 (6.4) | 12 (12.2) | 0.113 |

| Angina III/IV (%) | 23 (6.6) | 18 (7.2) | 5 (5.1) | 0.639 |

| Unstable angina (%) | 25 (7.2) | 21 (8.4) | 4 (4.1) | 0.241 |

| Syncope (%) | 96 (27.6) | 71 (28.4) | 25 (25.5) | 0.682 |

| Previous CVA (%) | 24 (6.9) | 17 (6.8) | 7 (7.1) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 35 (10.1) | 30 (12.0) | 5 (5.1) | 0.084 |

| Previous cardiac surgery (%) | 45 (12.9) | 33 (13.2) | 12 (12.2) | 0.951 |

| Previous AMI (%) | 17 (4.9) | 12 (4.8) | 5 (5.1) | 1.000 |

| Urgency/emergency surgery (%) | 7 (2.0) | 5 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Ischemia time (min) | 57.1±17.4 | 57.0±17.8 | 57.2±16.3 | 0.934 |

| CPB time (min) | 73.9±21.6 | 73.6±20.9 | 74.9±23.5 | 0.598 |

SAH = Systemic arterial hypertension; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass

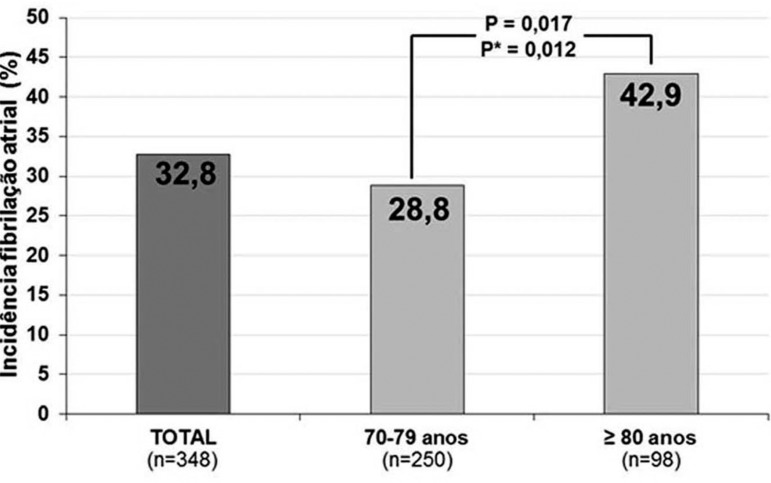

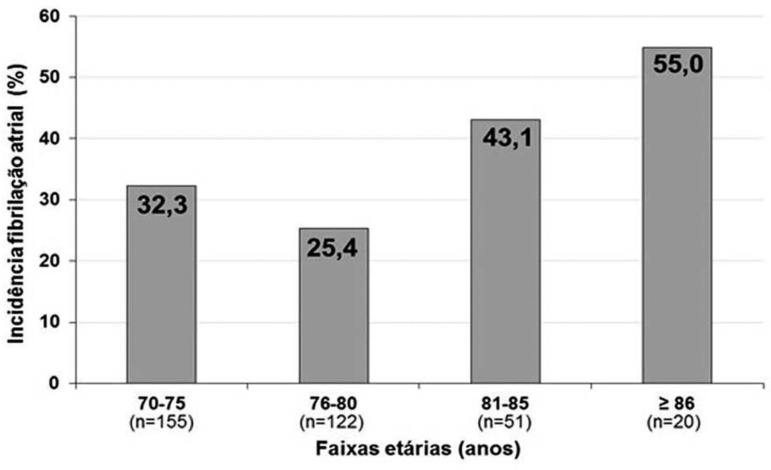

Incidence of postoperative AF was 32.8% (n=114). It was significantly higher (P=0.017) in patients aged > 80 years (42.9%) compared to those aged 70-79 years (28.8%), even when adjusted for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, previous smoking, peripheral vascular disease, and left ventricular ejection fraction (FEVE) < 40% in the multivariate analysis (P=0.012) (Figure 1). The relationship between age group and occurrence of AF can be seen in Figure 2, which shows borderline statistical significance for linear trend (P=0.055).

Fig. 1.

Incidence of postoperative atrial fibrilation after aortic stenosis surgery, total and according to age. *Adjusted for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, previous smoking, peripheral vascular disease, and LVEF < 40% . Incidência fibrilação atrial = Incidence of atrial fibrillation; total = total; anos = years.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between age and acute postoperative AF after aortic stenosis surgery. Borderline statistical significance for linear trend (P=0.055). Incidência fibrilação atrial = Incidence of atrial fibrillation. Faixas etárias (anos) = Age

The analysis of patients who did and those who did not suffer from postoperative AF did not identify characteristics or risk factors with statistically significant differences between those two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of patients with acute postoperative AF.

| Variable | AF | no AF | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=114) | (n=234) | ||

| Average age (years) | 77.4±5.2 | 76.5±4.3 | 0.101 |

| Male patients (%) | 59 (51.8) | 136 (58.1) | 0.314 |

| SAH (%) | 84 (73.7) | 167 (71.4) | 0.745 |

| Diabetes (%) | 23 (20.2) | 54 (23.1) | 0.635 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (%) | 24 (21.1) | 38 (16.2) | 0.341 |

| COPD (%) | 14 (12.3) | 24 (10.3) | 0.700 |

| Previous smoking (%) | 44 (38.6) | 103 (44.0) | 0.398 |

| Current smoking (%) | 3 (2.6) | 7 (3.0) | 1.000 |

| Heart failure III/IV (%) | 48 (42.1) | 84 (35.9) | 0.316 |

| LVEF < 40% (%) | 7 (6.1) | 21 (9.0) | 0.483 |

| Angina III/IV (%) | 7 (6.1) | 16 (6.8) | 0.987 |

| Unstable angina (%) | 7 (6.1) | 18 (7.7) | 0.760 |

| Syncope (%) | 35 (30.7) | 61 (26.1) | 0.435 |

| Previous CVA (%) | 8 (7.0) | 16 (6.8) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 10 (8.8) | 25 (10.7) | 0.714 |

| Previous cardiac surgery (%) | 11 (9.6) | 34 (14.5) | 0.270 |

| Previous AMI (%) | 4 (3.5) | 13 (5.6) | 0.571 |

| Urgency/emergency surgery (%) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (2.1) | 1.000 |

| Ischemia time (min) | 58.5±14.8 | 56.3±18.5 | 0.273 |

| CPB time (min) | 74.8±16.5 | 73.5±23.8 | 0.622 |

AF = atrial fibrillation; SAH = Systemic arterial hypertension; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass

In patients with acute AF, there was a slightly higher, but statistically insignificant, incidence of postoperative CVA. On the other hand, patients with this arrhythmia had a significantly longer Intensive Care Unit and total hospital stay, even in the multivariate analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of hospital mortality. Those analyses are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Incidence of CVA, hospital length of stay, and hospital mortality according to the incidence of postoperative AF.

| Complication | Total | AF | no AF | P | P * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=348) | (n=114) | (n=234) | |||

| CVA (%) | 7(2.0) | 3 (2.6) | 4 (1.7) | 0.687 | - |

| Hospital length of stay | |||||

| Median days of ICU stay (25-75%) | 3 (2-5) | 5 (3-7) | 3 (2-4) | < 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Median days of total stay (25-75%) | 8 (7-13) | 10 (8-15) | 8 (7-10) | < 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Outcome | |||||

| Mortality (%) | 25 (7.2) | 5 (4.4) | 20 (8.5) | 0.234 | - |

AF = atrial fibrillation; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; ICU = Intensive Care Unit. (25-75%) = 25-75% interquartile range.

Adjusted for age

DISCUSSION

By evaluating elderly patients who underwent aortic valve replacement, this study observed an almost linear trend of age and incidence of postoperative AF, with individuals aged > 86 years presenting a 55% rate of this arrhythmia. In addition, hospital length of stay was longer for this population, both total and in the ICU, but incidences of CVA and hospital mortality were not higher.

Postoperative arrhythmias have multifactorial etiology, but it has been suggested that, in the postoperative period, they are mainly a result of incomplete myocardial protection. Oxygen-derived free radicals and calcium overload resulting from reperfusion of ischemic areas are important arrhythmogenic mechanisms that lead to transmural reentry [8].

Some studies have found advanced age, male gender, previous AF, HF, and beta blocker withdrawal as being preoperative factors associated with higher incidence of AF. Even though a number of studies have shown risk factors for postoperative AF following cardiac surgery, an effective prediction model has yet to be developed [9]. A Brazilian study conducted by Silva et al. [4] analyzed the occurrence of AF in 452 patients who underwent cardiac surgery and developed a score to predict this arrhythmia. Factors most associated with AF included patients aged 75 years and older, mitral valve disease, no use of beta blocker, beta blocker withdrawal, and positive fluid balance. The absence of risk factors reflected a 4.6% chance of postoperative AF and for one, two, and three or more risk factors, the chance was 16.6%, 25.9%, and 46.3%.

A previous study that analyzed only patients who underwent aortic valve replacement found that age, previous history of paroxysmal AF, supraventricular heart rate of > 300 bpm in 24 hours, and supraventricular tachycardia on the day before surgery were independent predictors of postoperative paroxysmal AF [10]. In this study, only patients with aortic stenosis were included, without correlating with either beta blockers or fluid balance; however, age was confirmed as an independent risk factor.

Likewise, in other series, advanced age is considered an independent predictor for postoperative AF following cardiac surgery. It has been described that this arrhythmia affects more than 18% of individuals over 60 years old and about 50% of those over 80 years old who underwent CABG [3]. The literature reports any patient over 70 years old who underwent CABG as being at a high risk for developing AF. Furthermore, it is known that for every 10-year increase in patient's age, the risk of developing postoperative AF following cardiac surgery increases 75% [8,11,12]. This association is because these individuals have more comorbidities related to age as well as structural changes in the atrial myocardium, such as distension and fibrosis, which are secondary to changes typical of old age [3]. In this study, which included only patients aged > 70 years, besides a high overall occurrence rate of AF (32.8%), there was also a linear increase with age, as described above; however, the increase was not statistically significant.

Despite being often considered a harmless temporary problem, postoperative AF is associated with an increase in early and late mortality [13], as it has been shown in meta-analysis [14]. High incidence of postoperative AF after cardiac surgery warns of the importance of identifying patients at high risk of developing this arrhythmia [8].

Even though risk factors for postoperative AF are known in a substantial number of patients, when analyzed individually no single risk factor could be identified. That justifies the importance of establishing prophylaxis in order to reduce the incidence of this arrhythmia and consequently its clinical implications to patients who underwent cardiac surgery [3]. Several studies have evaluated the effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological prophylactic interventions in the prevention of postoperative AF.

Meta-analysis was used to assess the impact of those interventions, including amiodarone, beta blockers, sotalol, magnesium, atrial stimulation, and posterior pericardiotomy. All of those significantly reduced the rate of postoperative AF after cardiac surgery. The prophylactic interventions reduced hospital length of stay by about 16 hours and hospital expenses by approximately USD 1,250. In addition, they reduced the occurrence of postoperative CVA, though this reduction was not statistically significant (OR 0.69; CL 95% 0.47-1.01), and they did not affect mortality, neither cardiovascular nor by any other cause [2].

The administration of beta-blocking agents is the most effective measure in AF prophylaxis [3], significantly reducing its incidence after cardiac surgery (OR 0.33; CL 95% 0.26-0.43) [2]. As part of the routine at our institution, every patient starts to receive this class of drugs on the first postoperative day, unless there are contraindications such as hemodynamic instability.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, which could have influenced the quality and uniformity of the data collected; being performed at one single institution, which makes it difficult to make generalizations from the data presented; and the relatively small sample, which could have impacted, for example, the failure to observe a relationship between AF and incidence of CVA and mortality.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, incidence of postoperative AF after aortic valve stenosis surgery in patients aged > 70 years proved high and linearly correlated with advanced age, reaching 55% in patients aged 85 years and older. As a result, there was an increase in ICU and total hospital length of stay; however, there was no increase in morbidity and mortality of affected patients. Knowledge of those data is important to show the need for prophylactic measures and early treatment of this arrhythmia in this subgroup in order to minimize morbidity and postoperative length of stay.

| Abbreviations, acronyms & symbols | |

|---|---|

| CVA | Cerebrovascular accident |

| CCS | Canadian Cardiovascular Society |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| HF | heart failure |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| Authors’ roles & responsibilities | |

|---|---|

| FPJ | Research plan and design; data collection; data analysis and interpretation; statistical analysis; writing of the manuscript |

| GFTF | Data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript |

| JRMS | Data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript |

| PMP | Data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript |

| PRP | Data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript |

| IAN | Data analysis and interpretation; critical review of the manuscript |

| RAKK | Research plan and design; data analysis and interpretation; statistical analysis; writing of the manuscript |

Footnotes

No financial support.

Work carried out at the Cardiology Institute/University Foundation of Cardiology (IC/FUC), Cardiovascular Surgery Service and Graduate Program, and at the Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Surgical Clinic Department, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arsenault KA, Yusuf AM, Crystal E, Healey JS, Morillo CA, Nair GM, et al. Interventions for preventing post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD003611. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003611.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferro CR, Oliveira DC, Nunes FP, Piegas LS. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;93(1):59–63. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2009000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valle FH, Costa AR, Pereira EM, Santos EZ, Pivatto F, Júnior, Bender LP, et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients aged over 75 years undergoing surgery for aortic valve replacement. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;94(6):720–725. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2010005000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva RG, Lima GG, Guerra N, Bigolin AV, Petersen LC. Risk index proposal to predict atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2010;25(2):183–189. doi: 10.1590/s0102-76382010000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geovanini GR, Alves RJ, Brito G, Miguel GA, Glauser VA, Nakiri K. Postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: who should receive chemoprophylaxis? Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;92(4):326–330. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2009000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, Rizzo RJ, Couper GS, VanderVliet M, et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery. Current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation. 1996;94(3):390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaman AG, Archbold RA, Helft G, Paul EA, Curzen NP, Mills PG. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a model for preoperative risk stratification. Circulation. 2000;101(12):1403–1408. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogue CW, Jr, Hyder ML. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac operation: risks, mechanisms, and treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(1):300–306. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rho RW. The management of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Heart. 2009;95(5):422–429. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaw R, Hernandez AV, Masood I, Gillinov AM, Saliba W, Blackstone EH. Short- and long-term mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(5):1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlowska-Baranowska E, Baranowski R, Michalek P, Hoffman P, Rywik T, Rawczylska-Englert I. Prediction of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis: identification of potential risk factors. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12(2):136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogue CW, Jr, Creswell LL, Gutterman DD, Fleisher LA, American College of Chest Physicians Epidemiology, mechanisms, and risks: American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for the prevention and management of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2005;128(2) Suppl:9S–16S. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2_suppl.9s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariscalco G, Engström KG. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: risk factors and their temporal relationship in prophylactic drug strategy decision. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129(3):354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echahidi N, Pibarot P, O'Hara G, Mathieu P. Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(8):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]