Abstract

RNase E is an endonuclease that plays a central role in RNA processing and degradation in Escherichia coli. Like its E. coli homolog RNase G, RNase E shows a marked preference for cleaving RNAs that bear a monophosphate, rather than a triphosphate or hydroxyl, at the 5′ end. To investigate the mechanism by which 5′-terminal phosphorylation can influence distant cleavage events, we have developed fluorogenic RNA substrates that allow the activity of RNase E and RNase G to be quantified much more accurately and easily than before. Kinetic analysis of the cleavage of these substrates by RNase E and RNase G has revealed that 5′ monophosphorylation accelerates the reaction not by improving substrate binding, but rather by enhancing the catalytic potency of these ribonucleases. Furthermore, the presence of a 5′ monophosphate can increase the specificity of cleavage site selection within an RNA. Although monomeric forms of RNase E and RNase G can cut RNA, the ability of these enzymes to discriminate between RNA substrates on the basis of their 5′ phosphorylation state requires the formation of protein multimers. Among the molecular mechanisms that could account for these properties are those in which 5′-end binding by one enzyme subunit induces a protein structural change that accelerates RNA cleavage by another subunit.

Messenger RNAs are labile molecules whose longevity directly influences the synthesis rates of the proteins they encode. Despite the importance of mRNA degradation for gene expression, little is understood about the molecular mechanisms that govern differences in mRNA stability, even in so well studied an organism as Escherichia coli. Elucidating these mechanisms is crucial for explaining how RNA sequence and structure control mRNA lifetimes.

The degradation of most E. coli mRNAs is thought to begin with internal cleavage by the endonuclease RNase E (1), although in some cases decay begins instead with cleavage by RNase III or RNase G (an RNase E homolog) (2, 3). The resulting mRNA fragments are then degraded to mononucleotides by a combination of further endonucleolytic cleavage and 3′ exonucleolytic digestion.

RNase E is a 1,061-aa protein comprising functionally distinct domains. The catalytically active amino-terminal half of the protein (N-RNase E: residues 1–498) is alone sufficient for the enzyme's ribonuclease activity, whereas the carboxyl half of the protein (residues 499-1061) contains both an arginine-rich region and a carboxy-terminal domain that serves as a scaffold for the assembly of a multiprotein complex known as the RNA degradosome (4, 5). By contrast, RNase G, which comprises 489 amino acid residues, is similar in sequence to the amino half of RNase E but lacks an arginine-rich region and a scaffold domain (6, 7).

In view of the homology of RNase G to the catalytic domain of RNase E, it is not surprising that they have a similar cleavage site specificity, with both preferring to cut RNA within single-stranded regions that are AU-rich (8, 9). Another important property shared by these two endonucleases is their preference for RNA substrates that bear a single phosphate group at an unpaired 5′ end. Remarkably, such substrates are cleaved by full-length RNase E, N-RNase E, or RNase G more than an order of magnitude faster than otherwise identical RNAs bearing a 5′-terminal triphosphate or hydroxyl group, even though cleavage may occur far from the 5′ end (9–11). The greater susceptibility of 5′-monophosphorylated RNAs to cleavage by these enzymes may help to ensure the rapid degradation of the downstream products of initial endonucleolyic cleavage, which differ from their primary-transcript precursors in being 5′-monophosphorylated rather than 5′-triphosphorylated. Besides helping to minimize the accumulation of downstream mRNA fragments that could serve as templates for the synthesis of aberrant protein products if not promptly destroyed, this property is also likely to contribute to segmental differences in stability within polycistronic transcripts.

Almost nothing is known about the mechanism by which a monophosphate at the 5′ end of an RNA molecule is able to influence the rate of ribonuclease cleavage at an internal site that may be far downstream. Within the catalytic domain of these enzymes, there presumably is a site that can interact productively with RNA 5′ ends that are monophosphorylated but not with those that bear a triphosphate or hydroxyl, yet the presence of such a 5′-end-binding site has not been verified empirically. In principle, the interaction of RNase E or RNase G with the 5′ terminus of a monophosphorylated RNA could accelerate cleavage either by improving the binding affinity of the RNA substrate or by enhancing the catalytic activity of the enzyme. However, even this fundamental question has remained unanswered, in large part because the electrophoretic methods typically used to monitor RNA cleavage by these two ribonucleases have been inadequate for detailed kinetic analysis.

Here we report the design and use of a pair of fluorogenic RNA substrates whose cleavage by RNase E or RNase G can readily be monitored in real time. With these substrates, we have performed detailed kinetic studies of N-RNase E and RNase G. These studies have revealed that the presence of a monophosphate at the 5′ end of an RNA stimulates cleavage by increasing the catalytic efficiency of these enzymes rather than the binding affinity of the RNA substrate and that a 5′ monophosphate can also enhance the specificity of cleavage site selection within an RNA. Additional experiments indicate that each of these ribonucleases must form a homodimer or higher-order multimer for this activation to occur. Together, these findings provide a framework for understanding how the phosphorylation state of the 5′ end is able to influence internal RNA cleavage at distant sites by RNase E and RNase G.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Plasmids. Plasmid pNRNE7000, a derivative of pNRNE1000 (11), encodes the first 499 amino acid residues of E. coli RNase E fused at the carboxyl terminus to a hexahistidine affinity tag and a c-Myc epitope tag (GGAAAHHHHHH-VAAEQKLISEEDLNGAARS). Plasmid pRNG1101 encodes E. coli RNase G tagged at the carboxyl terminus with the heptapeptide GHHHHHH (12). Plasmids pMAL-NRNE and pMAL-RNG encode chimeras in which E. coli maltose binding protein has been fused to the amino terminus of E. coli N-RNase E or RNase G, respectively.

Protein Purification. N-RNase E and RNase G bearing a hexahistidine tag were purified from E. coli containing pNRNE7000 or pRNG1101, as described (11). MBP-N-RNase E and MBP-RNase G were purified from lysates of BL21(DE3) containing pMAL-NRNE or pMAL-RNG by affinity chromatography on amylose resin (New England Biolabs). Protein concentrations were determined colorimetrically.

RNA Cleavage Assays. The f luorogenic oligonucleotides P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD were synthesized and HPLC-purified by Xeragon (Huntsville, AL). Internally radiolabeled RNA I.26 bearing a 5′ monophosphate or 5′ triphosphate was synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase, as described (11). RNA cleavage was carried out at 25°C in a buffer containing Tris·Cl (25 mM, pH 7.5), MgCl2 (10 mM), NaCl (20 mM), DTT (0.1 mM), and glycerol (5% vol/vol). The cleavage reactions were monitored either continuously by fluorometry with a FluoroMax-2 spectrofluorimeter (excitation at 495 nm; emission at 517 nm) or discontinuously by gel electrophoresis of samples quenched at time intervals with EDTA, followed by analysis with a Molecular Dynamics FluorImager.

Assays of Protein Multimeric State. The subunits of protein multimers were covalently crosslinked in RNA cleavage buffer lacking DTT by treatment with 1,8-bis-maleimidotriethyleneglycol [BM(PEO)3; 3 M, Pierce] for 1 h at room temperature. The protein samples were then dialyzed, concentrated, and analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis. Protein bands were detected by staining with Coomassie blue or by immunoblot analysis with anti-Myc (Zymed Laboratories) or anti-RNase G (a kind gift from G. A. Mackie) antibodies.

Results

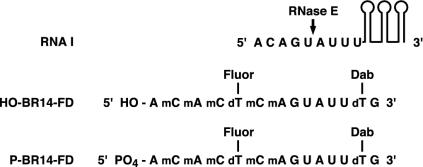

A Fluorogenic Substrate for RNase E and RNase G. To allow RNA cleavage by RNase E and RNase G to be monitored in real time under initial reaction conditions, we developed an oligonucleotide substrate whose digestion by these enzymes results in a marked increase in fluorescence. The sequence of this RNA substrate (BR14-FD; Fig. 1) resembled the 5′-terminal segment of pBR322 RNA I, an untranslated regulatory RNA that contains a single major RNase E cleavage site (13). The key features of the synthetic substrate were a fluorescein tag upstream of the expected RNase E cleavage site and a fluorescence-quenching dabcyl tag downstream of the cleavage site. The bulky fluorescein tag was surrounded by three extra nucleotides to increase its distance from both the 5′ end and the cleavage site. In addition, five of the nucleotides upstream of the cleavage site were 2′-O-methylated to protect them from RNase E digestion (14).

Fig. 1.

Fluorogenic RNA substrates. Sequence of fluorogenic oligonucleotide substrates in comparison to the segment of RNA I that is cleaved by RNase E. Fluor, fluorescein; Dab, dabcyl. For RNA I, the sequence of only the first nine nucleotides is shown, whereas the three tandem stem-loops that comprise the 3′ portion of RNA I are represented diagrammatically. The principal RNase E cleavage site within the 5′-terminal segment of RNA I is marked with an arrow.

This oligonucleotide substrate, bearing either a 5′-terminal hydroxyl (HO-BR14-FD) or a 5′-terminal monophosphate (P-BR14-FD), was chemically synthesized and purified. Upon complete cleavage by a truncated form of E. coli RNase E (N-RNase E) comprising the catalytic amino-terminal half of the protein (residues 1–499) fused at its carboxyl terminus to an affinity/epitope tag, there was a 30-fold increase in fluorescence at 517 nm due to release of the dabcyl tag, which had quenched most fluorescein fluorescence in the uncleaved RNA (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

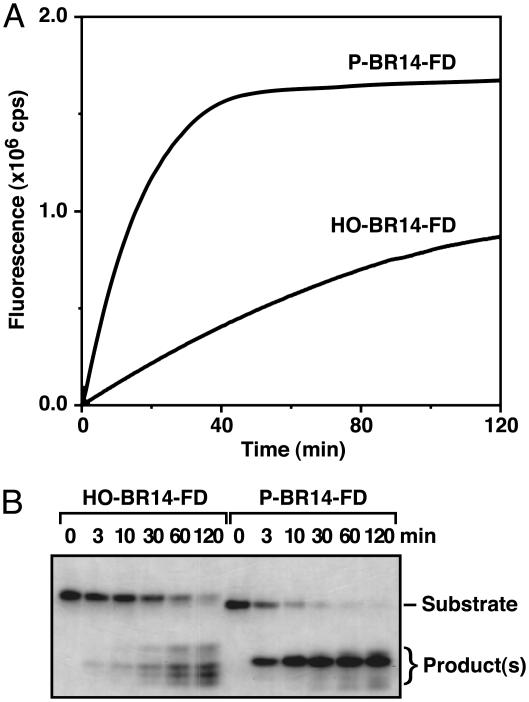

To confirm that this increase in fluorescence accurately reflected the extent of RNA cleavage, N-RNase E digestion of P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD was monitored by both fluorometry and gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). As measured by either of these assays, the time course of a cleavage reaction performed under the same reaction conditions was very similar, with the substrate bearing a 5′ phosphate being cleaved 7- to 10-fold faster than the 5′ hydroxyl substrate. As expected, the initial cleavage rates were dependent on the enzyme concentration and saturable at high substrate concentrations (data not shown). Interestingly, whereas N-RNase E cleaved P-BR14-FD at a unique site, its cleavage site specificity was reduced in the absence of the 5′ phosphate. The slow cleavage of HO-BR14-FD to form multiple fluorescent products was Mg2+ dependent and was unaffected by placental ribonuclease inhibitor. Moreover, an N-RNase E variant impaired by mutation of Lys-112 (15) but purified in an identical manner produced the same HO-BR14-FD cleavage products at a diminished rate (data not shown). These findings indicate that the reduction in cleavage site specificity observed for the 5′ hydroxyl substrate is an intrinsic property of N-RNase E.

Fig. 2.

Fluorometric and electrophoretic assays of enzyme-catalyzed BR14-FD cleavage. (A) Continuous fluorometric assays comparing the cleavage of P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD (1 μM) by N-RNase E (50 nM). (B) Discontinuous electrophoretic assays of P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD cleavage by N-RNase E, performed under the same conditions as in A and analyzed on a 16% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel. Note the greater cleavage site heterogeneity for the 5′-hydroxyl substrate. Similar results were obtained with RNA substrates lacking 2′-O-methyl groups. The relatively high fluorescence of the uncleaved substrate RNAs in the electrophoretic assay compared to their low fluorescence in solution apparently is caused by spatial separation of the fluorophore and quencher under denaturing conditions, as a similar increase in fluorescence is observed in solution when 7 M urea is present.

Catalytic Activation of RNase E and RNase G by a Substrate Bearing a 5′-Terminal Phosphate. The molecular mechanism by which a 5′-terminal monophosphate can markedly accelerate internal RNA cleavage by RNase E or RNase G is not understood. In principle, this rate acceleration could be a consequence of tighter binding of the 5′-monophosphorylated RNA and/or catalytic activation of the enzyme by this form of the substrate. These two possible explanations can be distinguished by comparing the Michaelis–Menten kinetic parameters kcat and Km for cleavage of substrates bearing a 5′ phosphate versus a 5′ hydroxyl.

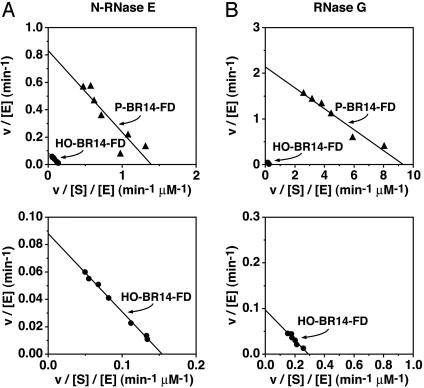

To measure kcat and Km for the two fluorogenic substrates, various concentrations of P-BR14-FD or HO-BR14-FD were combined with a limiting amount of N-RNase E, and the initial rate of RNA cleavage was measured by fluorometry. The data were then analyzed on an Eadie–Hofstee plot to allow kcat (y intercept) and Km (slope) to be calculated for each substrate (Fig. 3A). Whereas kcat was nine times greater for the monophosphorylated substrate (0.83 ± 0.06 min-1) than for the otherwise identical substrate lacking a 5′-phosphate (0.088 ± 0.002 min-1), their Km values were nearly identical (0.60 ± 0.07 μM for P-BR14-FD versus 0.57 ± 0.02 μM for HO-BR14-FD). Similar results were obtained by using E. coli RNase G as a catalyst instead of N-RNase E (Fig. 3B). In the case of RNase G, the increase in kcat for the monophosphorylated RNA (2.1 ± 0.1 min-1) versus the hydroxyl RNA (0.096 ± 0.010 min-1) was somewhat larger (22-fold), but once again the Km values for the two substrates were similar (0.23 ± 0.03 μM for P-BR14-FD versus 0.33 ± 0.05 μM for HO-BR14-FD). These findings indicate that the presence of a monophosphate at the 5′ end of RNA accelerates its cleavage by RNase E or RNase G by catalytically activating these enzymes rather than by increasing the binding affinity of the RNA substrate.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the Michaelis–Menten parameters for ribonucleolytic cleavage of substrates bearing a 5′ monophosphate versus a 5′ hydroxyl. Cleavage of P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD by N-RNase E (75 nM) (A) or RNase G (20 nM) (B) was monitored continuously by fluorometry, and the initial reaction rates measured at various substrate concentrations (0.08–1.20 μM for N-RNase E and 0.05–0.50 μM for RNase G) were graphed as Eadie–Hofstee plots (v, reaction rate; [S], substrate concentration; [E], enzyme concentration). The y intercept of such plots equals kcat, and the slope equals -Km.Inthe two upper graphs, the data for both P-BR14-FD (triangles) and HO-BR14-FD (circles) are shown, whereas in the two lower graphs, the HO-BR14-FD data for N-RNase E (A) and RNase G (B) are replotted in a magnified view in which the scale of both axes has been reduced by a factor of 10.

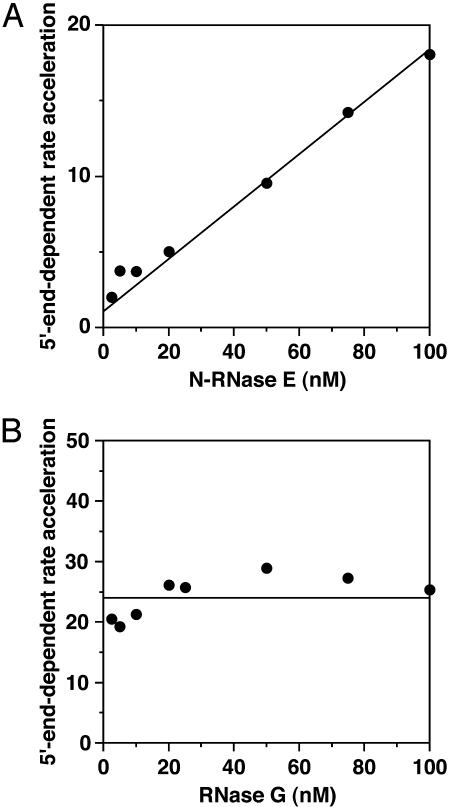

Importance of Enzyme Multimeric State for Activation. In the course of performing these rate measurements, we discovered that the degree to which a 5′-monophosphate facilitates cleavage by N-RNase E depends on the enzyme concentration. When assayed at a fluorogenic substrate concentration of 0.3 μM, the rate enhancement increased from 2-fold at an N-RNase E concentration of 2.5 nM to 18-fold at an N-RNase E concentration of 100 nM (Fig. 4A). Near the low end of this enzyme concentration range (5 nM N-RNase E), there was little difference in kcat and almost no difference in Km between the monophosphorylated substrate (kcat = 0.41 ± 0.02 min-1; Km = 0.50 ± 0.05 μM) and the hydroxyl substrate (kcat = 0.18 ± 0.02 min-1; Km = 0.39 ± 0.08 μM) (data not shown), whereas near the high end of the range (75 nM N-RNase E), kcat was much greater for the monophosphorylated substrate than for the hydroxyl substrate (0.83 ± 0.06 min-1 versus 0.088 ± 0.002 min-1; see above). By contrast, no significant concentration dependence was observed for RNase G, which cleaved P-BR14-FD 20–30 fold faster than HO-BR14-FD over a broad range of enzyme concentrations (Fig. 4B). The influence of N-RNase E concentration on catalytic activation by a 5′-monophosphate was independent of substrate length, as judged from an experiment in which the cleavage rates of a 130- to 185-nt radiolabeled RNA substrate (RNA I.26; ref. 11) bearing either a monophosphate or a triphosphate at the 5′ end were compared at two different N-RNase E concentrations (5 nM versus 75 nM) by an assay involving gel electrophoresis and autoradiography (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Once again, the rate enhancement observed for the monophosphorylated substrate was greater at the higher enzyme concentration.

Fig. 4.

Influence of enzyme concentration on the 5′-end dependence of N-RNase E and RNase G. The ratio of the cleavage rates of P-BR14-FD versus HO-BR14-FD (0.3 μM) is plotted as a function of N-RNase E (A) or RNase G (B) concentration.

The influence of protein concentration on the 5′-end dependence of N-RNase E suggested that the ability of a 5′-monophosphate to catalytically activate this ribonuclease might depend on the enzyme's multimeric state. Of relevance to this hypothesis are recent studies showing that RNase G exists primarily as a homodimer at moderate protein concentrations (16) and that N-RNase E exists primarily as a homotetramer at very high protein concentrations (17). That N-RNase E at lower concentrations can exist as a mixture of protein forms in different multimeric states was indicated by the results of gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions, which revealed both monomeric and dimeric forms of the protein (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

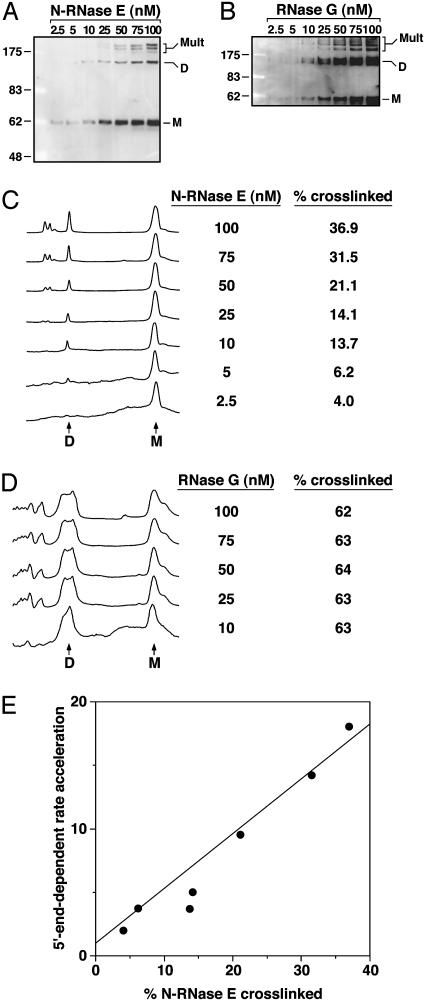

To corroborate the latter finding and extend it to a wide range of protein concentrations, we devised an assay of N-RNase E and RNase G multimeric state that involved chemical crosslinking followed by SDS/gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. N-RNase E at various concentrations was treated with the bifunctional cysteine-crosslinking reagent BM(PEO)3 to covalently join molecules that had formed multimers, and the crosslinked and uncrosslinked forms of the protein were resolved by electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (Fig. 5A). Quantitative comparison of the relative abundance of the different protein forms revealed a marked concentration dependence (Fig. 5C). At low concentrations, N-RNase E appeared to be almost entirely monomeric, whereas at higher concentrations a substantial fraction of the protein formed crosslinkable dimers and higher-order multimers. The concentration dependence of multimerization mirrored the effect of protein concentration on the degree to which N-RNase E could be activated by a 5′-monophosphorylated substrate (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that multimer formation by this enzyme is necessary for its catalytic activation by 5′-monophosphorylated RNA substrates. Depending on the crosslinking efficiency, we calculate that multimeric N-RNase E cleaves the phosphorylated substrate at least 18 times faster than the hydroxyl substrate, whereas monomeric N-RNase E has little, if any, preference for the substrate bearing a 5′-monophosphate.

Fig. 5.

Correlation of 5′-end dependence and protein multimeric state. (A) Chemical crosslinking of N-RNase E at various protein concentrations. Protein samples (2.5–100 nM subunit concentration) were treated with the bifunctional cysteine crosslinking reagent BM(PEO)3 and then analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting. Bands corresponding to monomers (M), crosslinked dimers (D), and crosslinked higher-order multimers (Mult) are marked. The left lane contains a set of protein molecular weight standards. Calibration is in kDa. (B) Chemical crosslinking of RNase G at various protein concentrations. Protein samples (2.5–100 nM subunit concentration) were crosslinked and analyzed by electrophoresis and immunoblotting as in A. (C) Quantitation of the N-RNase E crosslinking data. Traces depicting the relative band intensities in each lane of the immunoblot in A are shown, with vertical scales adjusted to equalize the areas of the monomer peaks. Beside each trace is listed the corresponding protein concentration and the percentage of protein subunits that became crosslinked at that concentration (dimers and higher-order multimers). Arrows identify peaks corresponding to monomer (M) and crosslinked dimer (D) bands. Peaks representing higher-order multimers are to the left of the dimer peak. (D) Quantitation of the RNase G crosslinking data. Vertically adjusted traces depicting the relative band intensities in each lane of the immunoblot in B are shown, along with protein concentrations and the percentage of protein subunits that became crosslinked at each concentration. Only the traces for RNase G concentrations ≥10 nM are shown, because the bands at lower concentrations were too weak to be quantitated. (E) 5′-end-dependent rate acceleration (P-BR14-FD versus HO-BR14-FD, 0.3 μM) as a function of percent crosslinked multimer, as measured at various N-RNase E concentrations (2.5–100 nM).

A similar crosslinking analysis was performed to assess the concentration dependence of RNase G multimerization (Fig. 5B). The yield of crosslinked RNase G was very high and essentially invariant over a wide range of protein concentrations (Fig. 5D). Assuming a crosslinking efficiency of 63% for multimeric RNase G under these reaction conditions, the data suggest that, unlike N-RNase E, this protein exists almost entirely as a dimer or higher-order multimer at the concentrations tested. This finding is consistent with recent sedimentation velocity studies (16) and with the lack of a significant effect of enzyme concentration on the marked 5′-end dependence of RNase G within this concentration range (Fig. 4B).

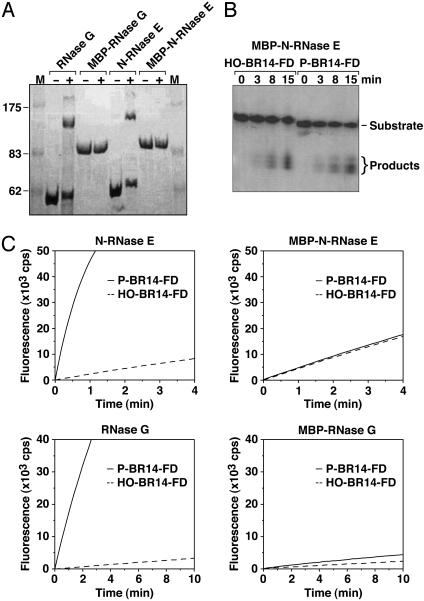

The importance of multimer formation for the accelerated cleavage of substrates bearing a 5′-monophosphate was confirmed by examining protein chimeras in which E. coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) was fused to the amino terminus of N-RNase E or RNase G. The presence of the MBP domain was found to prevent multimer formation by both of these proteins, as judged by crosslinking with BM(PEO)3 (Fig. 6A). As a consequence, the ability of N-RNase E and RNase G to cleave 5′-monophosphorylated RNA faster than 5′-hydroxyl RNA was virtually abolished in the context of these MBP chimeras (Fig. 6C). Moreover, both P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD were cut by MBP-N-RNase E with the reduced cleavage site specificity previously observed only for the 5′-hydroxyl substrate in digests by N-RNase E (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of an amino-terminal maltose-binding protein domain on the dimerization and 5′-end dependence of N-RNase E and RNase G. (A) Chemical crosslinking of N-RNase E, RNase G, MBP-N-RNase E, and MBP-RNase G. Samples of each protein (350 nM) were either treated with the cysteine crosslinking reagent BM(PEO)3 (+) or left untreated (-), and then analyzed by electrophoresis on an SDS/polyacrylamide gel beside a set of protein molecular mass standards (M). Bands for N-RNase E (59.1 kDa), RNase G (56.2 kDa), MBP-N-RNase E (99.3 kDa), and MBP-RNase G (98.4 kDa) were detected by staining with Coomassie blue. (B) Electrophoretic analysis of the cleavage of HO-BR14-FD and P-BR14-FD (0.3 μM) by MBP-N-RNase E (75 nM). (C) Comparative fluorometric analysis of the rate of cleavage of P-BR14-FD and HO-BR14-FD (0.3 μM) by N-RNase E versus MBP-N-RNase E and by RNase G versus MBP-RNase G (75 nM).

Discussion

For a variety of reasons, traditional electrophoretic techniques for monitoring RNA cleavage by RNase E or RNase G are not adequate for performing the initial rate measurements needed for in-depth kinetic analysis of enzyme function. Moreover, these methods are very slow and laborious. Even an improved analytical method that has recently been described (18) is based on a discontinuous assay in which reaction samples for each time point must be fractionated individually by chromatography.

The fluorogenic RNase E/G substrates that we have developed have a number of significant advantages. These RNAs are commercially available and nonradioactive, and they can be stored for prolonged periods without detriment. No specialized equipment is required to monitor their enzyme-catalyzed cleavage, which results in a marked increase in fluorescence that is readily quantifiable by using an ordinary fluorimeter. This continuous assay method allows initial reaction rates to be measured very quickly (several rate measurements can be completed per hour) and with a high degree of accuracy and sensitivity. Such an approach has been used in studies of RNase A (19, 20).

We have used a matched pair of fluorogenic substrates and either N-RNase E or RNase G to compare the Michaelis–Menten parameters kcat and Km for the cleavage of RNAs that differ only in their 5′ phosphorylation state. Our data show that the presence of a 5′-terminal monophosphate accelerates RNA cleavage by these enzymes not by increasing their RNA-binding affinity, as reflected by Km, but rather by enhancing their catalytic efficiency, as evidenced by a marked increase in kcat.

This finding has important implications for the molecular mechanism of the 5′-end dependence of RNase E and RNase G. Because a monophosphate at the RNA 5′ end is preferred over either a triphosphate, a hydroxyl, or an m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G cap (9–11), which are structurally dissimilar, it seems likely that a 5′-terminal monophosphate can interact physically with these ribonucleases and stimulate RNA cleavage rather than that each of the other 5′-terminal functional groups can interact in an inhibitory manner. Binding of the 5′ monophosphate appears to occur in conjunction with the binding of one or more 5′-terminal nucleotides, because the stimulatory effect of a 5′ monophosphate on RNase E is abolished by 5′-terminal base pairing (10). The free energy associated with the proposed interaction of the monophosphorylated RNA 5′ end with RNase E or RNase G apparently is used not to increase the strength of substrate binding but rather to augment the catalytic power of these enzymes. In principle, enzyme activation by a 5′ monophosphate bound outside the active site could be achieved through a change in protein conformation that improves the orientation and/or catalytic potency of important amino acid residues within the active site. Alternatively, a 5′-terminal monophosphate might be able to participate directly in catalysis by binding inside the active site together with the scissile phosphodiester bond and functioning as a catalytic group in RNA cleavage.

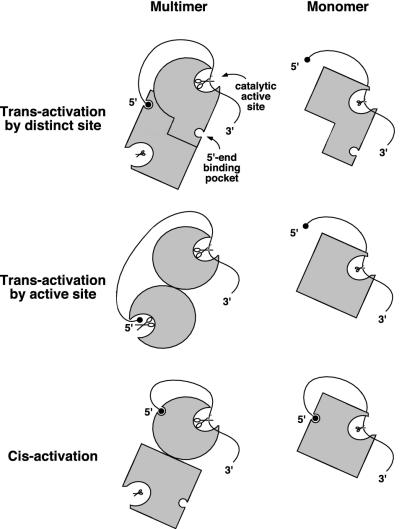

Our finding that the 5′-end dependence of N-RNase E and RNase G correlates with the formation of dimers and higher-order multimers indicates that multimerization is necessary for the catalytic activation of these enzymes by 5′-monophosphorylated RNA substrates. The influence of the enzymes' multimeric state on catalysis suggests specific mechanisms that could account for this property (Fig. 7). For example, if, in addition to a catalytic active site, each multimer subunit has a discrete 5′-end binding pocket that is functionally interconnected exclusively with the active site of another subunit, the occupancy of this 5′-end binding pocket would influence only the catalytic activity of the opposite subunit (trans-activation) and not that of the same subunit. Alternatively, the requirement for multimer formation would be explained if RNase E and RNase G cleave RNA via an alternating sites mechanism in which the active site of one multimer subunit functions as the 5′-end binding pocket that accelerates RNA cleavage by the active site of another subunit. An attractive feature of this model is that enzyme-catalyzed RNA cleavage would generate a new monophosphorylated 5′ end already bound at an active site, potentially facilitating further digestion of the 3′ cleavage product at downstream positions and thereby enhancing the processivity of mRNA decay (21). Finally, unlike the subunits of multimeric RNase E or RNase G, which may become activated when a monophosphorylated RNA 5′ end binds to the same subunit as the scissile phosphodiester bond (cis-activation), isolated monomers of these proteins might fold in a way that precludes their activation, either by inhibiting 5′-end binding or by preventing the bound 5′ end from enhancing catalysis.

Fig. 7.

Possible mechanisms for the multimerization dependence of 5′ activation of RNase E and RNase G. (Top) Transactivation by 5′-end binding to a distinct site on another subunit. (Middle) Transactivation by 5′-end binding to the active site of another subunit (alternating sites mechanism). (Bottom) Cis-activation by 5′-end binding to a site on the same subunit. In these models, catalytically activated RNase E/G subunits are depicted as round molecules that have a large pair of scissors in the active site, whereas unactivated RNase E/G subunits are drawn as rectangular molecules with a small pair of scissors in the active site. RNAs are represented as curved lines, and 5′-terminal monophosphates are represented as black circles.

Electrophoretic examination of the cleavage products of the fluorogenic oligonucleotides used in these studies indicates that 5′ monophosphorylation can both accelerate cutting at the primary RNA cleavage site and inhibit cleavage at nearby secondary sites. This increase in cleavage site specificity depends on the productive interaction of the RNA 5′ terminus with N-RNase E and can be abolished by an amino-terminal modification of N-RNase E that prevents the enzyme from cutting monophosphorylated RNA at a faster rate. Presumably, this interaction induces significant structural changes in the active site that both enhance catalytic activity and constrain substrate binding so as to restrict the enzyme's choice of cutting sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Atilio Deana for helpful comments on the manuscript. These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant GM35769.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviation: BM(PEO)3, 1,8-bis-maleimidotriethyleneglycol.

References

- 1.Mudd, E. A., Krisch, H. M. & Higgins, C. F. (1990) Mol. Microbiol. 4, 2127-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portier, C., Dondon, L., Grunberg-Manago, M. & Regnier, P. (1987) EMBO J. 6, 2165-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umitsuki, G., Wachi, M., Takada, A., Hikichi, T. & Nagai, K. (2001) Genes Cells 6, 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDowall, K. J. & Cohen, S. N. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 255, 349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanzo, N. F., Li, Y.-S., Py, B., Blum, E., Higgins, C. F., Raynal, L. C., Krisch, H. M. & Carpousis, A. J. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2770-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDowall, K. J., Hernandez, R. G., Lin-Chao, S. & Cohen, S. N. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 4245-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada, Y., Wachi, M., Hirata, A., Suzuki, K., Nagai, K. & Matsuhashi, M. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 917-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowall, K. J., Lin-Chao, S. & Cohen, S. N. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 10790-10796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tock, M. R., Walsh, A. P., Carroll, G. & McDowall, K. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8726-8732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackie, G. A. (1998) Nature 395, 720-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang, X., Diwa, A. & Belasco, J. G. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 2468-2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deana, A. & Belasco, J. G. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1205-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomcsanyi, T. & Apirion, D. (1985) J. Mol. Biol. 185, 713-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng, Y., Vickers, T. A. & Cohen, S. N. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14746-14751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diwa, A. A., Jiang, X., Schapira, M. & Belasco, J. G. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 46, 959-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briant, D. J., Hankins, J. S., Cook, M. A. & Mackie, G. A. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1381-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan, A. J., Grossmann, J. G., Redko, Y. U., Ilag, L. L., Moncrieffe, M. C., Symmons, M. F., Robinson, C. V., McDowall, K. J. & Luisi, B. F. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 13848-13855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redko, Y., Tock, M. R., Adams, C. J., Kaberdin, V. R., Grasby, J. A. & McDowall, K. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44001-44008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelenko, O., Neumann, U., Brill, W., Pieles, U., Moser, H. E. & Hofsteenge, J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 2731-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelemen, B. R., Klink, T. A., Behlke, M. A., Eubanks, S. R., Leland, P. A. & Raines, R. T. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 3696-3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coburn, G. A. & Mackie, G. A. (1999) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 62, 55-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.