Abstract

Population aging is a key public health issue facing many nations, and is particularly pronounced in many Asian countries. At the same time, attitudes toward filial obligation are also rapidly changing, with a decreasing sense that children are responsible for caring for elderly parents. This investigation blends the family versus nonfamily mode of social organization framework with a life course perspective to provide insight into the processes of ideational change regarding filial responsibility, highlighting the influence of education and international travel. Using data from a longitudinal study in Nepal—the Chitwan Valley Family Study—results demonstrate that education and international travel are associated with a decrease in attitudes toward filial obligation. However, findings further reveal that the impact of education and international travel vary both across the life course and by gender.

Keywords: attitudes toward elderly care, Nepal, education

Introduction

As the world’s population rapidly ages, elderly care is a key issue facing every nation. In many low-income countries, there is little to no social safety net for aging adults. At the same time, population-wide attitudes and beliefs are also changing, often with a decline in individuals’ sense of filial responsibility (Jayakody, Thornton and Axinn 2007). However, little research has provided a comprehensive look at what precipitates this change: what experiences influence individuals’ attitudes toward filial obligation? Nepal is one setting that has experienced substantial social change in recent decades, as well as an increasingly aging population (Axinn and Yabiku 2001; Chalise and Brightman 2006; Parker and Pant 2011; Thornton and Fricke 1987). Similar to other South Asian settings, government social security is limited and private pensions and health insurance are rare, leading parents to rely on younger generations for elderly care (Caldwell 1982; Niraula 1995; Willis 1980), particularly sons (Bennett 1983; Goldstein et al. 1983). Given Nepal’s recent social and demographic changes, it is an ideal context in which to investigate the confluence of these factors.

The broader literature on ideational change in rural settings suggests that, in Nepal, the recent shift in modes of social organization may be key to understanding individuals’ attitudes toward elderly care (Axinn and Yabiku 2001; Compernolle and Axinn 2014; Thornton and Fricke 1987; Thornton and Lin 1994; Yabiku, Axinn and Thornton 1999). More specifically, the transition away from social life centering on the family to social interactions occurring increasingly outside the home has had a profound influence on individuals’ attitudes, values, and beliefs across multiple domains. Two increasingly common experiences in Nepal that may significantly influence individuals’ attitudes toward filial responsibility are education and international travel—each of which have been shown to influence other family-related attitudes and beliefs (Barber 2004; Bongaarts and Watkins 1996; Boyd 1989; Easterlin 1980; Kalleberg 2009; Pienta, Barber and Axinn 2001). Drawing on a life course framework, the timing and sequencing of education and international travel may influence their impact on both the formation of and change in attitudes over time (Elder, Johnson and Crosnoe 2003; Krosnick and Alwin 1989). Research shows that early-life experiences exert particularly strong influence on subsequent attitudes (Alwin 1994; Alwin, Cohen, and Newcombe 1991; Axinn and Barber 2001; Elder 1977; Elder et al. 2003), thus highlighting the importance of considering the timing of education and travel when investigating their influence on attitudes.

In addition to a life course framework, the gendered nature of educational experiences, international travel, and elderly care suggest that these experiences might influence attitudes for men and women differently. In Nepal, there are sizeable gender-based inequalities in opportunities to both go to school and/or to travel internationally (Alexander and Eckland 1974; Cha 2010; Charles and Bradley 2009; Hochschild 1983, 1989; Morgan and Niraula 1995). The inequality in opportunities may work to reinforce gender differences by shaping individuals’ attitudes toward and expectations of social roles (Blair-Loy 2003; Chodorow 1995; Correll, Benard and Paik 2007; Goffman 1977; Martin 1996; West and Zimmerman 1987), including elderly care.

This study leverages newly available longitudinal data from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS) to provide a comprehensive analysis of how specific dimensions of social organization—education and international travel—influence attitudes regarding elderly care. The CVFS provides panel data on a sample of individuals, tracking their complete life experiences—including education and international travel—and attitudes toward filial responsibility over a twelve year period. The CVFS also features rich data on neighborhood-level access to schools and transportation. Additionally, the CVFS tracks respondents over the precise historical period in Nepal during which educational and travel opportunities rapidly expanded. Because most research on attitudes rely on cross-sectional data, or assess attitudes at only one point in time, the study’s longitudinal design provides a unique opportunity to determine what provokes 1) changes in attitudes toward filial responsibility and 2) how the timing and sequencing of experiences with education and international travel differentially influence attitudes between both men and women.

Theoretical framework

Social organization and attitudes toward caring for parents in old age

The family versus nonfamily mode of social organization framework posits that the nature of regular social interaction is largely influenced by the centrality of familial networks in daily activities (Thornton and Fricke 1987; Thornton and Lin 1994). As critical primary sources of information and learning, parents’ own preferences and behaviors influence children’s family formation attitudes (Axinn et al. 1994; Barber 2000; Elder, Liker and Cross 1984; Thornton 1980) through a combination of socialization and social control processes (Barber 2000). In agrarian communities in low-income countries—such as rural Nepal—because social life is largely organized around the family (Thornton and Lin 1994), with few outside sources of socialization, parents have considerable influence on their children’s attitudes. Rather, family serves as the center of social life, with limited time spent in schools and work occurring close to home. Of particular importance is the parent-child relationship, which remains a key source of emotional and financial support throughout the life course. For instance, because of limited formal employment opportunities outside the home, parental inheritance continues to be a primary source of wealth. As a result, young adults, particularly sons, continue to live with their parents well into adulthood (Cain 1981a, 1981b; Gertler and Lillard 1994). Even after entering marriage, which remains nearly universal, sons still tend to co-reside with parents (Caplan 2000; Gray 1995; Regmi 1999), resulting in a significant amount of time and opportunity for parents to influence their children’s attitudes.

Like many low-income countries, however, Nepal has experienced substantial social changes in recent decades. Specifically, through a combination of local initiatives and international aid, the Nepalese government encouraged settlement in the Chitwan Valley through land and infrastructural reforms, including the first all-weather road in 1979. These initiatives successfully encouraged settlers to take advantage of the rich soil and flat terrain. Subsequent increases in population and development led to the proliferation of nonfamily institutions, particularly education and monetary-based consumerism (Axinn and Yabiku 2001). Within the lifetime of its residents, for example, the number of schools has increased dramatically. In addition, increasing demand for labor abroad, coupled with eased migration policies and established networks, has led to a stark jump in out-migration and international travel rates from Chitwan in recent years. One driving force behind this increase in international travel is work: Nepalese are increasingly migrating to Gulf countries and other wealthier regions in search of two-year labor contracts as an alternative to the region’s inconsistent crop yields and stagnant economy (Kansakar 2003; Seddon et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012).

Such a shift toward more time spent with nonfamily members and institutions results in new socialization forces (Ghimire et al. 2006; Hoelter et al. 2004; Waite et al. 1986), which tend to emphasize individual freedoms and personal investment, rather than collectivist notions and respect for elders. For example, previous research shows that nonfamily living, formalized employment, and education reduce the desire for marriage and children (Axinn and Barber 1997; Coleman 1990; Thornton and Fricke 1987; Waite et al. 1986). Thus, with new nonfamily socialization forces currently unraveling in Nepal, it is reasonable to believe that education and international travel may influence attitudes toward caring for aging parents in such a setting,

Education

Mass education has strong effects on the spread of new belief systems, family preferences and behavior (Axinn and Barber 2001; Becker 1991; Caldwell 1982; Caldwell, Reddy and Caldwell 1988; Castro 1995; Cleland and Hobcraft 1985; Heck et al. 1997; Thornton and Lin 1994; Willis 1973). A principal explanation for the association between education and attitudinal change is its influence on everyday social interactions. Going to school exposes individuals to a unique social environment in which they are surrounded by peers who are their same age and are outside of their family network. This experience likely influences individuals’ attitudes in part because these influential networks are situated within a school setting, a nonfamily institution focused on individual growth and knowledge accumulation during early childhood—a critical time for forming attitudes (Alwin et al. 1991; Axinn and Yabiku 2001). These two factors—a period in the life course during which time individuals are particularly susceptible to socialization and a new institutional setting outside of the family—are strong determinants of attitude formation, and are likely to encourage individuals to adopt more individualistic perspectives (Thornton 2005). For instance, research shows that college experiences precipitate attitudinal shifts in young adults that remain stable throughout their lives (Alwin et al. 1991). Extensive research shows that education profoundly influences individuals’ attitudes, and shifts expectations away from historical family orientations toward those emphasizing personal development and independence (Waite et al. 1986; Goldscheider et al. 1986; Goldscheider and Waite 1991).

In addition to exposing individuals to new ideas through expanding nonfamily social networks, education is also likely to influence individuals’ attitudes toward filial responsibility through educational materials (Caldwell et al. 1988; Thornton 2005). In Nepal, schools often borrow models of education and classroom materials from richer European nations due in part to European colonization. As a result, educational materials disseminate ideas and values more prevalent in rich colonial settings, such as the United Kingdom and other European countries, through textbooks and syllabi (Brock-Utne 2000; Caldwell 1980; Thornton 2005). These materials promote individualism and smaller families by presenting the Western European ideal individual as educated, personally fulfilled, and financially successful and independent. In this sense, time spent enrolled in school both strengthens these individualistic attitudes as well as weakens those supporting opposite or competing behaviors such as those oriented toward the care of elderly kin (Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Ikamari 2003). Through exposure to nonfamily networks and educational materials originating from richer European nations, education is expected to influence attitudes to be less supportive of sons and daughters caring for parents in old age.

International travel

Just as education exposes individuals to new ideas via peer culture and curriculum materials, international travel is another influential nonfamily experience that is increasingly common among Nepalese. Much of the recent international travel from Chitwan is due to labor migration to Gulf and other industrialized countries (Kansakar 2003; Seddon et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012). Of course, individuals around the world and in Nepal have a long history of travelling for work. With more fluid borders and supportive labor policies, however, labor networks have been increasingly expanding beyond local contexts and across international lines. The global number of international migrants increased from 155.5 million in 1990 to an estimated 214 million in 2010 (UN DESA 2009).

Regardless of reasons for international travel, once individuals are abroad, they have multiple opportunities to interact and socialize with other young adults. Here, young migrants or travelers to these destinations are introduced to these new communication landscapes, leading to altered ideas that are shared among individuals and accelerating the diffusion of new or innovative ones (Bongaarts and Watkins 1996; Festinger 1954; Latane 1981). As migration tends to flow from poor societies such as rural South Asia, toward those with higher income, often closer to Europe, the ideas shared during this work experience may well reflect more Western beliefs. Research documents the decline of elderly support across diverse global contexts, including Gulf countries, as well as other family-related behaviors (El-Hadded 2003; Ogawa and Retherford 1993; Sibai and Yamout 2012). This international experience is expected to be particularly influential for Nepalese, as these foreign ideas are very different from those historically prevalent among their families in rural Nepal, regardless of whether in European or Gulf settings.

In addition to exposure to more individualistic networks, the very act of traveling abroad will foster a sense of individualism. Time spent away from family increases feelings of independence and reduces parental authority (Coleman 1990; Thornton and Lin 1994). Further, if linked with work, the income received abroad may increase individuals’ financial independence. This could potentially lead to increased autonomous economic decisions and/or the desire to live separately from their parents (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1987; Pienta et al. 2001). Importantly, the time away from family is likely to allow individuals to envision a future life that does not solely encompass caring for aging parents.

Gender differences in the link between social organization and attitudes toward old age care

In Asia, there are important gender differences in daily life—including education and travel opportunities (Bem 1993; Morgan and Niraula 1995; Risman 2004). Thus, it is possible that changes in both education and travel influence men’s and women’s attitudes toward social roles and filial responsibilities differently. Gendered social roles tend to be based on perceived differences between the sexes (Acker 1990; Rubin 1975; Scott 1986), and historically placed men in professional, public spheres outside the home, and women in the familial, private sphere inside the home (Landes 1988; Parsons and Bales 1955). South Asian women tend to be afforded fewer educational opportunities, and instead spend much of their time fulfilling domestic obligations (Beutel and Axinn 2002; Stash and Hannum 2001; Upadhyay 2002). On the other hand, South Asian male roles center on achieving high levels of education and financial stability, which enables them to provide for their family and their parents in later life (Bennett 1983; Gertler and Lillard 1994; Regmi 1999). In Nepal, international labor migration increasingly provides an avenue for achieving greater financial stability, thereby enabling men to better provide for their families (Alexander and Eckland 1974; Cha 2010; Charles and Bradley 2009; Hochschild 1983, 1989). The gendered differences in men’s and women’s social roles and opportunities in Nepal are likely to powerfully shape individuals’ attitudes and expectations of others (Blair-Loy 2003; Butler 1990; Chodorow 1989; Correll et al. 2007; Goffman 1977; Martin 1998; West and Zimmerman 1987).

In terms of education, men increase their human capital, and thus employment opportunities, by investing in education (Becker 1993; Blau and Duncan 1967; Coleman 1990; Jacobs 1996). In a setting in which married sons historically care for aging parents, this shift toward greater financial independence and exposure to more individualistic attitudes is likely to decrease men’s support for filial responsibilities more than it does for women. Additionally, because education increases one’s career prospects, it is expected to raise men’s and women’s expectations that men have a career, rather than just secure a job in farming or labor (Coleman 1990; Smith 1776; Thornton, Axinn and Xie 2007). As a result, the gap in preferences regarding sons and daughters caring for aging parents is expected to shift, reflecting individuals’ preferences that men, more so than women, make necessary investments for and prioritize a successful career, rather than more domestic tasks, such as caring for parents. In a setting like rural Nepal, this shift is reflected in a decrease, or a narrowing of the gap, between support for sons’ and support for daughters’ filial responsibilities. Lastly, as women’s opportunities to travel abroad tend to be limited, exposure to international networks might have a stronger influence on women’s attitudes toward elderly care than men’s.

Data and methods

The data for this study come from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS). Initiated in the early 1990s, the CVFS provides a unique opportunity to study how individuals’ educational and international travel experiences influence their attitudes toward filial care. Baseline individual and household interviews began in 1996, with 72-minute, face-to-face interviews conducted with all household members ages 15 to 59 and their spouses, regardless of age or place of residence, with a response rate of 97%. Individual life history calendars captured accurate annual retrospective data on schooling, travel, marital status, and childbearing events. After the 1996 baseline interview, respondents participated in household registries, which collected monthly information on family and life events. Using the regular monthly contact during this time, the 1996 respondents were re-interviewed in 2008, regardless of current place of residence. Because this study investigates changes in attitudes toward filial obligation, it focuses on the 95 percent of original respondents who also participated in the 2008 interview. The sample is further restricted to those between the ages of 15 and 25 years old to concentrate on the period in the life course during which time education and international travel typically occur (Alwin et al. 1991; Krosnick and Alwin 1989).

Attitudes toward old age care

Attitudes regarding elderly care were assessed by asking respondents whether married sons/daughters should care for their parents in old age. Attitude measures were assessed in 1996 and again in 2008 on a scale from one to three, with 1 indicating respondents “strongly agree”, 2 that they “somewhat agree,” and 3 that they “don’t agree at all” with the statement. Measures were reverse-coded so that higher numbers reflect more agreement with the statement, or more positive attitudes toward old age care.

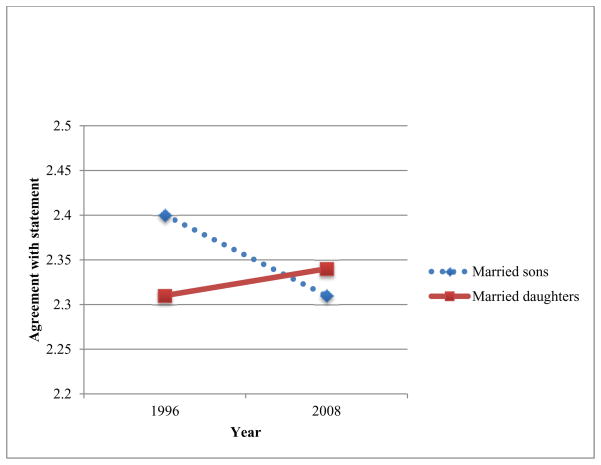

Descriptive statistics of study respondents and their attitudes toward elderly care are provided in Table 1. This table shows that between 1996 and 2008, attitudinal support for sons caring for aging parents declined significantly (2.40 to 2.31) while attitudinal support of daughters caring for aging parents increased significantly (2.29 to 2.34). Interestingly, in 2008 respondents reported slightly more favorable attitudes for daughters caring for elderly parents than for sons (2.34 to 2.31), but this difference is not statistically significant. Figure 1 presents a graphic picture of the convergence of the gendered difference in these attitudes.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (N = 1576)

| Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Attitudes | ||||

| Attitude in 1996: married son care for parents | 2.40 | .67 | 1 | 3 |

| Attitude in 2008: married son care for parents | 2.31 | .70 | 1 | 3*** |

| Attitude in 1996: married daughter care for parents | 2.29 | .64 | 1 | 3 |

| Attitude in 2008: married daughter care for parents | 2.34 | .64 | 1 | 3* |

| Education | ||||

| Educational attainment in 1996 | 6.39 | 3.59 | 0 | 14 |

| Educational attainment, 1996–2008 | .88 | 1.66 | 0 | 9 |

| International travel | ||||

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996 | .10 | .30 | 0 | 1 |

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996–2008 | .18 | .39 | 0 | 1 |

| Other key factors | .57 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | .57 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Family experiences | ||||

| Married in both 1996 and 2008 | .41 | .49 | 0 | 1 |

| Married in only 2008 | .49 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Not married in both 1996 and 2008 | .10 | .30 | 0 | 1 |

| Have children in 2008 | .71 | .45 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of siblings in 2008 | 8.29 | 4.2 | 0 | 29 |

| Ethnicity/caste | ||||

| Bhramin/Chhetri | .50 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Dalit | .10 | .29 | 0 | 1 |

| Hill Indigenous | .14 | .35 | 0 | 1 |

| Newar | .06 | .24 | 0 | 1 |

| Terai Indigenous | .20 | .40 | 0 | 1 |

| Respondent age 1996 | 19.44 | 3.2 | 15 | 25 |

Notes:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; two-tailed tests

Figure 1.

Change in attitudes toward sons and daughters caring for parents in old age, 1996–2008

Education

Educational attainment was assessed using a continuous indicator of the highest grade of school or year of college the respondent completed. This information was collected in a complete life history in 1996 and an updated life history in 2008. The nature of this measure allows one to account for both (1) educational attainment in 1996 and (2) change in education between 1996 and 2008. As shown in Table 1, average educational attainment was 6.4 years in 1996. Additional education attained between 1996 and 2008 was just under 1 year (.9 years).

International travel

In the life history calendar, respondents reported specific years in which they traveled outside of Nepal for one or more weeks during the study time frame. With these data, a dichotomous indicator of respondents’ international travel was created, coded 1 for any international travel. As shown in Table 1, 10 percent of respondents traveled outside Nepal prior to 1996, and 18 percent traveled internationally between 1996 and 2008.

Other key factors

In all models, a dummy variable was included to indicate whether the respondent is female (1) or male (0). In addition to gender, other demographic controls are accounted for, including (1) marital status (with a dichotomous indicator in 1996 and 2008), (2) whether the respondent has a child (measured in 2008), (3) number of siblings (measured in 2008), (4) ethnicity (Bhramin/Chhetri, Dalit, Hill Indigenous, Newar, and Terai Indigenous, Bhramin/Chhetri [ref]), and (5) age in years (in 1996).

As shown in Table 1, fifty-seven percent of the sample was female. Forty-one percent of respondents were married in 1996, with an additional 49 percent marrying by 2008 and ten percent never marrying. More than 70 percent had had children by 2008 (71 percent) and the mean number of siblings in 2008 was 8.3. Half of respondents were Bhramin/Chhetri (50 percent), followed by Terai Indigenous (20 percent), Hill Indigenous (14 percent), Dalit (10 percent) and Newar (6 percent). Average respondent age in 1996 was 19.4 years.

Analytic approach

A lagged dependent variable modeling approach was used to estimate the effects of education and international travel on the change in attitudes between 1996 and 2008, given that the earlier attitudes are held constant. The model can be represented as follows:

where Yt −1 is the attitude in 1996, x is an explanatory factor, and ε is the error term. Tables present estimates for β1 which represent the mean change in attitudes in 2008 for one unit of change in x while holding all other factors constant, including the same attitude measured exactly the same way in 1996 (Axinn and Thornton 1993). Because respondents are clustered within 151 neighborhoods, in all models, robust standard errors that account for the CVFS sampling design are generated.

Results

Education and International Travel

Table 2 presents estimates of the effects of education and international travel on attitudes toward old age care. First, attitudes toward married sons (models 1a–1c) and married daughters (models 2a–2c) changed between 1996 and 2008, regardless of educational attainment and international travel experience. Second, education does not significantly influence changes in these attitudes between the two time periods, net of other individual characteristics. However, while small, the direction of the effect of education attained during this time is in the expected direction: those with more years of education between 1996 and 2008 have slightly less support for both the attitude toward married sons (model 1a) and the attitude toward married daughters (model 2a) caring for their aging parents. Similarly, for those with more years of education attained prior to 1996, this educational experience continued to influence attitudes toward daughters caring for parents between 1996 and 2008: educational attainment in 1996 led to a small decrease in support of old age care in 2008.

Table 2.

Effects of education and international travel on the change in attitudes regarding married sons and daughters caring for parents in old age, 1996 – 2008

| Married sons caring for parents in old age | Married daughters caring for parents in old age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1a | 1b | 1c | 2a | 2b | 2c | |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Educational attainment, 1996 | .00 (.01) | .00 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | ||

| Educational attainment, 1996–2008 | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | ||

| International travel | ||||||

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996 | −.05 (.06) | −.05 (.06) | −.07 (.06) | −.06 (.06) | ||

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996–2008 | −.09* (.05) | −.09* (.05) | −.00 (.04) | .00 (.04) | ||

| Other key factors | ||||||

| Female | −.15*** (.03) | −.18*** (.04) | −.18*** (.04) | −.03 (.03) | −.02 (.03) | −.03 (.03) |

| Family experiences | ||||||

| Married in both 1996 and 2008 | .09 (.08) | .09 (.08) | .09 (.08) | .00 (.08) | .02 (.07) | .01 (.08) |

| Married in only 2008 | .16* (.08) | .16* (.08) | .16* (.08) | .02 (.07) | .02 (.07) | .02 (.07) |

| Have children in 2008 | −.02 (.05) | −.01 (.05) | −.01 (.05) | .04 (.05) | .04 (.05) | .04 (.05) |

| Number of siblings in 2008 | −.00 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | .01 (.00) | .01 (.00) | .01 (.00) |

| Ethnicity/caste | ||||||

| Dalit | −.03 (.06) | −.04 (.05) | −.03 (.06) | −.05 (.07) | −.02 (.06) | −.05 (.07) |

| Hill Indigenous | −.04 (.05) | −.03 (.05) | −.04 (.05) | .06 (.05) | .08* (.04) | .06 (.05) |

| Newar | .08 (.07) | .07 (.07) | .07 (.07) | .07 (.07) | .07 (.07) | .06 (.07) |

| Terai Indigenous | .13** (.05) | .12*** (.05) | .12* (.05) | .04 (.05) | .07 (.04) | .03 (.05) |

| Respondent Age in 1996 | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| Attitude in 1996 | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) | .15*** (.03) | .15*** (.03) |

| Intercept | 2.19*** (.19) | 2.15*** (.17) | 2.20*** (.19) | 2.10*** (.17) | 1.98*** (.15) | 2.09*** (.17) |

| N | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 |

| R-Sq | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

Notes: Each column represents a linear regression model. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; one-tailed tests

Third, models 1b and 2b present estimates of the effects of international travel on attitudes. Results show individuals who traveled outside Nepal between 1996 and 2008 had significantly less support for sons caring for parents in old age, agreeing to the statement .09 points less than those individuals who did not travel (p<.05). Similar to education, international travel experience prior to 1996, while not significant, also operates in the expected direction: those who traveled outside Nepal before 1996 had decreased support for both sons (model 1b) and daughters caring for parents in old age (model 2b). In full models including educational attainment and international travel both prior to 1996, as well as between 1996 and 2008 (models 1c and 2c), results reveal decreased support for filial responsibilities in 2008. However, only the effect of international travel between 1996 and 2008 on attitudes toward sons caring for aging parents is significant.

Gender differences in the effects of Education and International Travel

Table 2 shows that attitudes toward caring for aging parents are different for women and men. Women are significantly less supportive of sons’ filial responsibilities than men are, net of 1996 attitudes, with attitudes toward sons caring for parents in old age (model 1c) .18 points lower than men’s (p<.001). Women are also less supportive of daughters caring for parents than men, although this effect is much smaller and not significant (model 2c).

Table 3 shows estimates of the gendered effects of educational attainment on the change in attitudes toward sons (models 1and 1b) and daughters (2a and 2b) caring for their aging parents. Results demonstrate several points. First, among women and men with no education, women have significantly less support than men for sons caring for parents in old age (p<.001), as well as for daughters caring (p<.01, model 2a). Second, the effects of education, both prior to 1996 and between 1996 and 2008, on both of these attitudes are negative: men with more years of education both before and after 1996 have decreased support for filial responsibilities than men who attained less education during this time. The effects of education prior to 1996 are significant for men for both attitudes: each additional year of education attained before 1996 leads to a .02 decrease in men’s support for sons caring for aging parents (p<.05, model 1a) and a .03 decrease in men’s support for daughters caring for aging parents (p<.01, model 2a), respectively.

Table 3.

Gendered effects of education on the change in attitudes regarding married sons and daughters caring for parents in old age, 1996 – 2008

| Sons caring for parents in old age | Daughters caring for parents in old age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| Educational attainment, 1996 | −.02* (.02) | .00 (.01) | −.03** (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| Educational attainment, 1996–2008 | −.01 (.01) | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | −.03* (.01) |

| Education*Female interactions | ||||

| Education (1996) * Female | .03** (.01) | .03*** (.01) | ||

| Education (1996–2008) * Female | .02 (.02) | .03* (.02) | ||

| Other key factors | ||||

| Female | −.33*** (.07) | −.17*** (.04) | −.22** (.07) | −.06 (.04) |

| Family experiences | ||||

| Married in both 1996 and 2008 | .08 (.08) | .09 (.08) | −.00 (.08) | −.00 (.07) |

| Married in only 2008 | .16* (.08) | .15* (.08) | .02 (.07) | .01 (.7) |

| Have children in 2008 | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.05) | .04 (.05) | .04 (.05) |

| Number of siblings in 2008 | −.00 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | .01 (.00) | .01 (.00) |

| Ethnicity/caste | ||||

| Dalit | −.04 (.06) | −.03 (.05) | −.06 (.07) | −.05 (.07) |

| Hill Indigenous | −.03 (.05) | −.04 (.05) | .07 (.05) | .06 (.05) |

| Newar | .07 (.07) | .08 (.07) | .06 (.07) | .06 (.07) |

| Terai Indigenous | .13** (.05) | .13** (.05) | .04 (.05) | .04 (.05) |

| Respondent Age in 1996 | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| Attitude in 1996 | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) | .14*** (.03) |

| Intercept | 2.28*** (.20) | 2.22*** (.19) | 2.21*** (.17) | 2.15*** (.17) |

| N | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 |

| R-Sq | 5.7 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

Notes: Each column represents a linear regression model. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; one-tailed tests

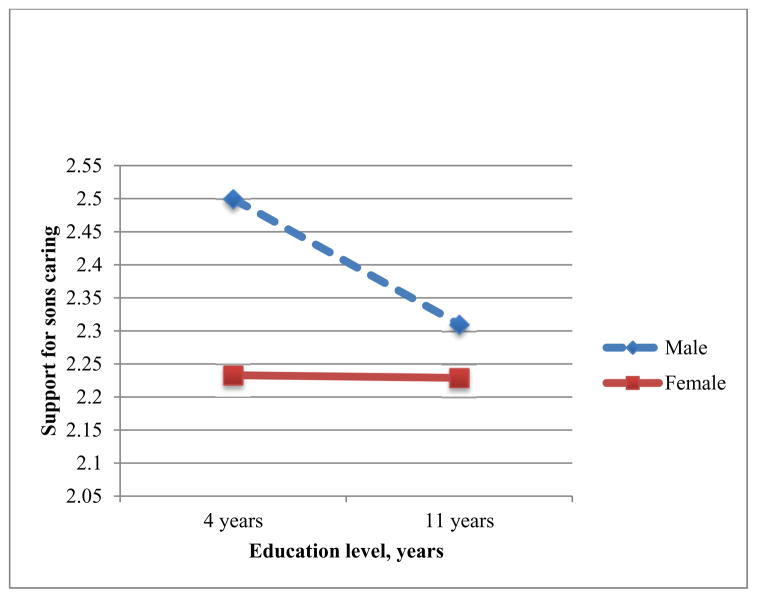

In addition, the effect of education in 1996 is significantly different for men’s and women’s attitudes (p<.01 for attitudes toward sons caring, model 1a, and p<.001 for attitudes toward daughters caring, model 2a). While the effects of education (for men) and being female (with no education) are both negative, the positive interaction suggests that education decreases men’s support for these attitudes more than it does for women; in other words, the effect is less negative for women. Figure 2 presents predicted attitudes toward married sons caring for parents in old age for men and women of varying levels of educational attainment in 1996. Men and women with four years of education are on the left and men and women with eleven years of education are on the right. While women with less education are less supportive than men with the same level of education, the difference in support of elderly care between men and women with more education is much narrower (shown on the right)—men’s attitudinal support decreases more with each additional year of education. This figure depicts the significant interaction between education and gender: the negative association between education prior to 1996 and old-age attitudes is significantly stronger for men than it is for women.i

Figure 2.

Gender and education (prior to 1996) on attitude toward sons caring for parents in old age

The effect of educational attainment between 1996 and 2008 also varies by gender. This interaction is also positive for both attitudes (models 1b and 2b), although only significantly different for men’s and women’s attitudes toward daughters caring for parents in old age (p<.05). Together, the four models presented in Table 3 point to the importance of education in shaping attitudes, regardless of when the years of schooling were attained. Importantly, results indicate that education occurring earlier in the life course continues to have strong effects on attitudes later on in life, and that these effects are particularly strong for men. Education occurring later—between 1996 and 2008—is important as well, also more so for men than women, although is not as influential on attitudes as education occurring earlier on.

I also test whether the effects of international travel on attitudes toward elderly care vary by gender. Similar to education, the effects of travel outside Nepal influence men’s and women’s attitudes differently (results not presented for parsimony). The interactions, however, are in the opposite direction of that between education and gender: international travel between 1996 and 2008 decreases women’s support for sons caring for aging parents significantly more than it decreases men’s support (p<.05). Similarly, international travel prior to 1996 decreases women’s support for daughters caring more than it decreases men’s (p<.05).

Education, International Travel and the gap in gendered attitudes

Table 4 presents estimates of education and international travel on the change in the gap between the two attitudes, or the gap between support for sons caring for parents in old age and support for daughters caring for parents in old age. This model combines the outcome attitudes modeled in Tables 2 and 3, offering a different perspective on respondents’ preferences about who exactly should be caring for aging parents—sons or daughters—and how strongly they prefer one over the other to perform this behavior. Again, the gap is measured by subtracting support for daughters caring for parents from the support for sons caring for parents, meaning that a positive coefficient indicates more support for sons over daughters. Conversely, a negative coefficient indicates less support of sons over daughters. Because sons historically care for parents in old age, a decreasing gap might also signal a flattening out of elderly care preferences.

Table 4.

Effects of education and international travel on the change in the gap in whether married sons should care for parents and whether married daughters should, 1996 – 2008

| Education | |

| Educational attainment, 1996 | .01 (.01) |

| Educational attainment, 1996–2008 | −.00 (.01) |

| International travel | |

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996 | .01 (.07) |

| Travel outside Nepal, 1996–2008 | −.09* (.05) |

| Other key factors | |

| Female | −.16*** (.05) |

| Family experiences | |

| Married in both 1996 and 2008 | .08 (.09) |

| Married in only 2008 | .13* (.08) |

| Have children in 2008 | −.05 (.05) |

| Number of siblings in 2008 | −.01 (.01) |

| Ethnicity/caste | |

| Dalit | .01 (.07) |

| Hill Indigenous | −.10* (.05) |

| Newar | .00 (.07) |

| Terai Indigenous | .08 (.06) |

| Respondent Age in 1996 | −.01 (.01) |

| Attitude in 1996 | .10*** (.03) |

| Intercept | .13 (.19) |

| N | 1576 |

| R-Sq | 4.4 |

Notes: Each column represents a linear regression model. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; one-tailed tests

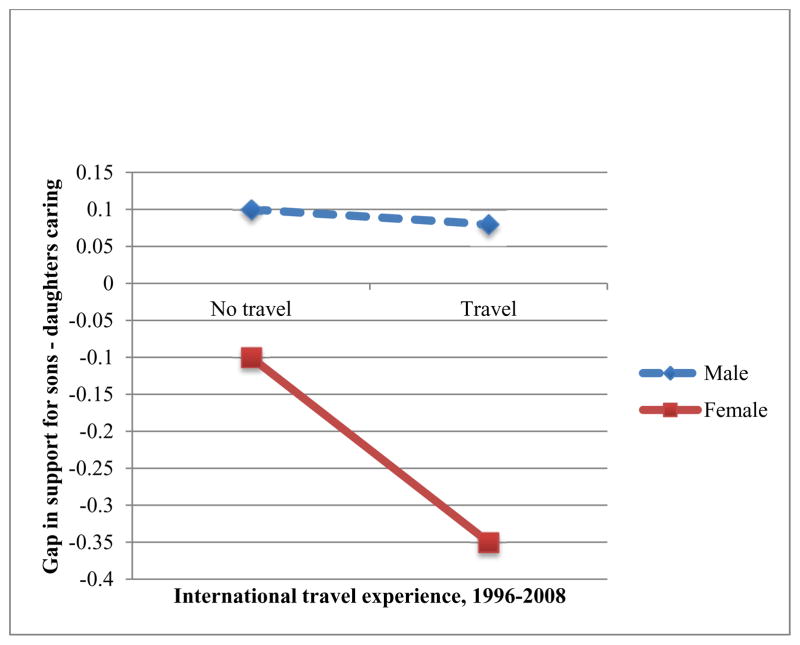

Table 4 reveals several patterns. First, the effect of being female is negative and significant (p<.001), suggesting that the gap between preferences for sons and daughters caring for parents in old age is significantly smaller for women than for men; in other words, women do not have a strong preference for sons caring, compared to men (p<.001). Second, findings also demonstrate that international travel is an important experience influencing the change in the gap in support for sons’ and daughters’ filial responsibilities. Like gender, international travel between 1996–2008 has a negative effect on the change in the gap, meaning that individuals who traveled abroad during this time period have weaker preferences regarding who—sons or daughters—should care for aging parents (p<.05). Rather, those who traveled outside Nepal have more similar attitudes toward sons’ and daughters’ filial roles than those who did not travel during this time. Additional models (not presented for parsimony) tested whether this effect of international travel varied by gender. Similar to previous interactions with gender, international travel experience between 1996 and 2008 influences the change in the gap differently for men and women, as is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Gender and international travel on the gap between sons and daughters caring for parents in old age

In this model, the effect for female remains significant and negative (p<.01), meaning that among men and women who did not travel internationally, women had a much smaller difference between attitudes than men did. The effect of international travel (for men) remains negative although is no longer significant. The interaction between travel and female is negative and significant (p<.05), suggesting that for women who travelled outside Nepal during this time, the gap in support between sons and daughters narrowed even more than for men who traveled during this time. Thus, men and women with no international travel experience between 1996–2008 (on the left) have larger gaps than men and women who did travel (on the right), and this difference due to travel is much larger for women than for men.

Discussion

Attitudes toward old age care have changed in recent decades, with senses of filial responsibility declining worldwide (Jayakody et al. 2007; Ogawa and Retherford 1993; Pienta et al. 2001; Sibai and Yamout 2012). This study finds evidence of similar changes in attitudes in rural Nepal: overall, men and women grow less supportive of sons and daughters caring for parents in old age. Importantly, two key factors influence these changes, both of which underscore the importance of social experiences occurring outside the family. First, educational attainment affects attitudes toward sons and daughters caring for elderly parents: additional years of education are associated with decreased support for elderly care. This finding is consistent with literature documenting the importance of education on attitude formation and change (Alwin et al. 1991; Axinn and Yabiku 2001; Caldwell 1980). Two mechanisms operating to influence attitudes here are different elements of education related to the sharing of information: both the novel, nonfamily networks in a school setting and educational materials originating in more industrialized countries tend to promote ideas associated with individualism and personal freedoms (Thornton 2005). These networks and their attitudes contrast with those more historically prevalent in rural Nepal, which tend to emphasize and center on the family (Waite et al. 1986; Goldscheider and Waite 1991).

Second, international travel is another important nonfamily experience influencing changes in attitudes toward elderly care. Similar to education, travel outside Nepal exposes individuals to new settings and social interactions. Given the nature of recent international travel from Nepal, this migration is to more industrialized and Gulf countries for work (Seddon et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012). These international channels of communication and networks diffuse ideas more prevalent in Western settings, which tend to center more on materialism and individualism, and less on collectivism and kinship obligations (Bongaarts and Watkins 1996; Thornton 2005). International travel also influences attitudes toward elderly care through a heightened sense of individualism gained while abroad. Both time spent away from parents and, if linked to work, financial independence may lead to decreased parental authority and increased desire to lead more separate lives as adult children, resulting in a declined sense of filial responsibility.

Findings also indicate that these effects of education and international travel vary both across the life course and for young women and men. Overall, education, regardless of timing, is negatively associated with support for elderly care (Tables 2 and 3). The experience of education, however, influences women’s and men’s attitudes differently. While the effects of education prior to 1996 (for men) and being female (with no education) significantly and negatively influence attitudes toward elderly care, the interaction between education and female is positive (Table 3). This shows that education is influential overall, but is particularly stronger both for men than for women, as well as when occurring earlier in life: each year of education attained prior to 1996 decreases men’s support for elderly care more than it does women’s. Additional education attained between 1996 and 2008 also affects men’s attitudes more negatively than women’s, although the effect is weaker. These findings that education occurring earlier in life is more influential than exposure to such networks or materials later on is not surprising (Alwin et al. 1991). However, how the timing of enrolment in school affects attitudes later on in life in such a setting as rural Nepal has not been previously documented.

The effect of international travel on attitudes toward filial responsibility also varies by life course timing and gender. While travelling abroad at any time point decreases support for elderly care, international travel experience later on, between 1996 and 2008, is found to be particularly influential (Table 2). The experience was especially powerful for women: those who traveled during this time period had significantly less support for sons and daughters caring for aging parents than women who did not travel.

That the effects of education and international travel vary based on when they are experienced and who is experiencing them is important. It suggests that both dimensions of social organization, as well as attitudes toward old care, remain deeply connected to gendered social roles and expectations (Beutel and Axinn 2002; Thornton et al. 2007) – particularly in a setting in which sons historically care for aging parents. Education led to a larger decline in men’s support for elderly care than women’s, reflecting perhaps their own heightened expectations that they focus on financial endeavors and securing a successful career, rather than on filial obligations. That education prior to 1996 was more influential than education attained 1996–2008 suggests that men develop career goals and aspirations at younger ages, and these ideas affect their attitudes toward social roles in subsequent years. The decrease in the gap between attitudes similarly demonstrated this shift in expectations: that support for sons’ filial responsibilities decreased more than changes in daughters’ shows increased preferences for men to invest in education and financial independence over caring for aging parents (Thornton et al. 2007).

Importantly, these changes in attitudes have serious implications for future changes in how individuals think about and care for those in old age. The overall decrease in support for children, particularly sons, caring for parents in old age is due in part to changes in education and international travel. Enrollment in school and international travel have increased significantly in recent decades, both in Nepal and worldwide. These trends are expected to continue as mass and higher education continues to spread, and as movement, particularly labor, becomes increasingly more mobile across more fluid international borders. In this sense, education and international travel can be expected to continue to influence attitudes toward elderly care, with future attitudes supporting filial responsibilities even less. As changes in attitudes promote changes in associated behaviors (Ajzen 1988), continued decreased support for children caring for aging parents will shift old care to occur more and more outside the family – a shift that has started to occur due in part to nonfamily experiences (Brauner-Otto 2009; Yarger and Brauner-Otto 2014). Such changes present real challenges for policy makers in settings like Nepal, as well as other settings with aging populations and experiencing social change, which struggle to provide for a growing elderly population. A better understanding of how individuals are changing to think about elderly care allows for appropriate investments in infrastructure to address these challenges, such as non-family services and institutions that can address this gap in care.

Biography

Ellen Compernolle is a Doctoral Candidate in Sociology and the Population Studies Center in the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. Her research interests include family demography, development, international migration, social change, and gender.

Footnotes

This effect is also evident in additional models (not presented for parsimony) that flip the gender measure: in models that include a binary indicator for male and an interaction effect for male and education, the main effect for education remains negative, while the main effect for males is positive and the interaction effect between male and education is negative. These results mirror those presented in Table 3: women on average have less support for elderly care, education on average decreases support for elderly care, and education decreases men’s support for elderly care more for than it does women’s.

References

- Acker Joan. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen Icek. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Karl L, Eckland Bruce K. Sex differences in the educational attainment process. American Sociological Review 1974 [Google Scholar]

- Alwin Duane, Cohen Ronald L, Newcome Theodore M. The women of Bennington: A study of political orientations over the life span. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alwin Duane. Aging, personality, and social change: the stability of individual differences over the adult life span. In: Featherman DL, Lerner RM, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-Span Development and Behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 135–85. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G, Barber Jennifer S. Living Arrangements and Family Formation Values in Early Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(3):595–611. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William, Barber Jennifer. Mass education and fertility transition. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):481–505. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William, Yabiku Scott. Social change, the social organization of families and fertility limitation. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(5):1219–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S. Intergenerational influences on the entry into parenthood: Mothers’ preferences for family and nonfamily behavior. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):319–348. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S. Community social context and individualistic attitudes toward marriage. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(3):236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. Human Capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with Special Reference to Education. 3. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bem Sandra Lipsitz. The lenses of gender: transforming the debate on sexual inequality 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Lynn. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters. New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel Ann M, Axinn William G. Gender, social change and educational attainment. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2002;51(1):109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Blair-Loy Mary. Competing devotions: career and family among women executives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Peter M, Duncan Otis Dudley. The American Occupational Structure. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld Hans-Peter, Huinink Johannes. Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(1):143–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Watkins Susan. Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review. 1996;22(4):639–682. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Monica. Family and personal networks in international migration: recent developments and new agendas. International Migration Review. 1989;23(3):638–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner-Otto Sarah R. Schools, schooling and children’s support of their ageing parents in rural Nepal. Ageing and Society. 2009;10(1):1015–1039. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock-Utne Birgit. Gender trouble. Routledge, Butler, Judith; Routledge: 2000. Whose education for all?: The recolonization of the African mind. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cain Mead. Risk and Insurance: Perspective on Fertility and Agrarian Change in India and Bangladesh. Population and Development Review. 1981a;7(30):435–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cain Mead. Perspective on Family and Fertility in Developing Countries. Population Studies. 1981b;36(2):159–75. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1982.10409026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John. Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and Development Review. 1980;6(2):225–255. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John. Theory of fertility decline. London: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John, Reddy PH, Caldwell Pat. The Causes of Demographic Change: Experimental Research in South India. Madison: WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan Lionel. Land and Social Change in East Nepal: A Study of Hindu-tribal Relation. 2. Himal Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Martin T. Women’s education and fertility: results from 26 demographic and health surveys. Studies in Family Planning. 1995;26(4):187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha Youngjoo. Reinforcing ‘separate spheres’: the effect of spousal overwork on the employment of men and women in dual-earner households. American Sociological Review. 2010;75(2):303–329. [Google Scholar]

- Chalise Hom Nath, Brightman James D. Aging trends: Population aging in Nepal. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. 2006;6(3):199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Maria, Bradley Karen. Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregations by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2009;114(4):924–976. doi: 10.1086/595942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow Nancy. Family Structure and Feminine Personality. Feminism in the Study of Religion. 1995:61–80. (1974) [Google Scholar]

- Cleland John, Hobcraft J., editors. Reproductive changes in developing countries: Insights from the World Fertility Survey. London, England: Oxford University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Compernolle Ellen L, Axinn William G. Social organization and social psychology: Mass education, international travel, and ideal ages at marriage. PSC working paper. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13524-019-00838-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll Shelly J, Benard Stephen, Paik In. Getting a job: is there a motherhood penalty. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(5):1297–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin Richard. Birth and fortune: the impact of numbers of personal welfare. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hadded Yahya. Major trends affecting families in Gulf countries. Major trends affecting families: A background document 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H., Jr Family history and the life course. Journal of Family History. 1977;2(4):279–304. doi: 10.1177/036319907700200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H, Jr, Liker Jeffrey K, Cross Catherine E. Parent-child behavior in the Great Depression: Life course and intergenerational influences. In: Baltes P/B, Brim OG Jr, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Vol. 6. New York: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 109–158. [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H, Jr, Johnson Monica K, Crosnoe Robert. The emergence and development of the life course. In: Mortimer Jeylen T, Shanahan Michael J., editors. Handbook of the life course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger Leon. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler Paul J, Lillard Lee A. Introduction: The Family and Intergenerational Relations. The Journal of Human Resources. 1994;29(4):941–949. Special Issue: The Family and Intergenerational Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire Dirgha, Axinn William, Yabiku Scott, Thornton Arland. Social change, premarital nonfamily experience and spouse choice in an arranged marriage society. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111(4):1181–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman Irving. The arrangement between the sexes. Theory and Society. 1977;4(3):301–331. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances Kobrin, Waite Linda J. Sex differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology. 1986;7(1):91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances K, Waite Linda J. New Families, No Families? The Transformation of the American Home. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Calvin, Goldscheider Frances K. Moving out and marriage: what do young adults expect? American Sociological Review. 1987;52:278–85. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Melvyn, Schuler Sidney, Ross James L. Social and Economic Forces Affecting Intergenerational Relations in Extended Families in a Third World Country: A Cautionary Tale from South Asia. Journal of Gerontology. 1983;38(6):716–724. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray John N. The Householder’s World: Purity, Power and Dominance in a Nepali Village. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heck Catherine E, Schoendorf Kenneth C, Ventura Stephanie J, Kiely John L. Delayed childbearing by education level in the United States, 1969–1994. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 1997;1(2):81–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1026218322723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Arlie. The managed heart: the commercialization of human feelings. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Arlie. The second shift. New York, NY: Viking; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelter Lynette F, Axinn William G, Ghimire Dirgha J. Social change, premarital nonfamily experiences, and marital dynamics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(5):1131–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Ikamari Lawrence DE. The effect of education on the timing of marriage in Kenya. Demographic Research. 2003;12(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Jerry A. Gender inequality and higher education. American Review of Sociology. 1996;22:153–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody Rukmalie, Thornton Arland, Axinn William. International Family Change: Ideational Perspectives. Routledge: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. Precarious work, insecure workers: employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review. 2009;74(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kansakar Vidya BS. Population Monograph of Nepal. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics; 2003. International migration and citizenship in Nepal; pp. 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick Jon A, Alwin Duane. Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(3):416–425. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes Joan B. Women in the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution. Cornell University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Latane B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist. 1981;36(4):343. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Karin. Puberty, sexuality, and the self: boys and girls at adolescence. Psychology Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Niraula Bhanu. Gender inequality and fertility in two Nepali villages. Population and Development Review. 1995;21(3):541–61. [Google Scholar]

- Niraula Bhanu B. Old age security and inheritance in Nepal: Motives versus means. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1995;27(1):71–78. doi: 10.1017/s002193200000701x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Naohiro, Retherford Robert D. Care of the elderly in Japan: Changing norms and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 55(3):585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Sara, Pant Bijan. Longevity in Nepal: health, policy and service provision c challenges. International Journal of Society Systems Science. 2011;3(4):333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Talcott, Bales Robert F. Family, Socialization and Interaction Process. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Pienta Amy Mehraban, Barber Jennifer S, Axinn William G. Social change and adult children’s attitudes toward support of elderly parents: Evidence from Nepal. Hallym International Journal of Aging. 2001;3(2):211–235. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi RR. Dimensions of Nepali Society and Culture. SAAN Research Institute; Gairidhara, Kathmandu: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Risman Barbara. Gender as a social structure: theory wrestling with activism. Gender and Society. 2004;18(4):429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Gayle. The traffic of women: notes on the ‘political economy’ of sex. In: Reiter Rayna., editor. Toward an Anthropology of Women. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Seddon David, Adhikari Jagannath, Gurung Ganesh. Foreign labor migration and the remittance economy of Nepal. Critical Asian Studies. 2002;34(1):19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Joan. Gender: a useful category of historical analysis. American Historical Review 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan Michael. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:667–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sibai Abla Mehio, Yamout Rouham. Family-based old-age care in Arab countries: between tradition and modernity. Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries. 2012:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: Strahan and Cadell; 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Stash Sharon, Hannum Emily. Who goes to school? Educational stratification by gender, caste, and ethnicity in Nepal. Comparative Education Review. 2001;45(3):354–378. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. The Influence of first generation fertility and economic status on generation fertility. Population and Environment. 1980;3:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. Reading History Sideways: The fallacy and enduring impact of the developmental paradigm on family life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Fricke Tom. Social change and the family: Comparative perspectives from the West, China, and South Asia. Sociological Forum. 1987;2(4):746–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Lin HS. Social Change and the Family in Taiwan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Axinn William G, Xie Yu. Marriage and Cohabitation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) Trends in International Migrant Stock: the 2008 Revision 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay Bhaumna. Gender roles in rural communities of Nepal. Asian Women. 2002;14(6):81–202. [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J, Goldscheider Frances K, Witsberger Christina. Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review. 1986;51:541–554. [Google Scholar]

- West Candace, Zimmerman Don H. Doing Gender. Gender and Society. 1987;1(2):125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Nathalie, Thornton Arland, Ghimire Dirgha J, Young-DiMarco Linda. Nepali Migrants to the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Values, Behaviors, and Plans. In: Kamrava M, editor. Migrant Labor in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willis Robert. A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81(part 2 supp):S14–S64. [Google Scholar]

- Willis Robert. The old age security hypothesis and population growth. In: Burch T, editor. Demographic behavior: Interdisciplinary perspectives on decision-making. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1980. pp. 43–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku Scott T, Axinn William G, Thornton Arland. Family Integration and Children’s Self-Esteem. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;104:1494–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Yarger Jennifer, Brauner-Otto Sarah R. Non-family experience and receipt of personal care in Nepal. Ageing and Society. 2014;34(1):106–128. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12000815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]