Abstract

Background

We performed a systematic review of patient satisfaction studies in the Plastic Surgery literature. The specific aim was to evaluate the status of satisfaction research that has been undertaken to date and to identify areas for improvement.

Methods

Four medical databases were searched using satisfaction and Plastic Surgery related search terms. Quality of selected articles was assessed by two trained reviewers.

Results

Out of the total of 2,936 articles gleaned by the search, 178 were included in the final review. The majority of the articles (58%) in our review examined patient satisfaction in breast surgery populations. Additionally, 53% of the articles were limited in scope and only measured features of care in one or two domains of satisfaction. Finally, the majority of the studies (68%) were based solely on the use of ad-hoc satisfaction measurement instruments that did not undergo a formal development.

Conclusion

Given the important policy implications of patient satisfaction data within Plastic Surgery, we found a need to further refine research on patient satisfaction in Plastic Surgery. The scarcity of satisfaction research in the craniofacial, hand, and other reconstructive specialties, as well as the narrow scope of satisfaction measurement and the use of unvalidated instruments are current barriers preventing Plastic Surgery patient satisfaction studies from producing meaningful results.

Keywords: Systematic Review, Patient Satisfaction, Plastic Surgery

In 1966, public health icon Avedis Donabedian wrote that the ultimate determinant of a treatment’s quality is its effectiveness in “producing health and satisfaction.”1 Since its establishment as a treatment outcome, many experts have argued that patient satisfaction would have important policy implications2–4. In 1978, John Ware contended that satisfaction data were the “indicator of the structure and process” of a healthcare encounter and should be used in setting the priorities of health organizations and programs, as well as in planning health and medical care research5.

In contrast to using traditional outcomes measures such as mortality and morbidity, Plastic Surgery is a quality of life specialty in which the satisfaction of the patient may be the most important outcomes metric in determining whether the patient will return for additional reconstructive or aesthetic procedures. Especially for aesthetic surgery, understanding factors that influence patient satisfaction is a requisite for maintaining a successful practice. Knowledge of these factors allows practitioners to change aspects of their care that adversely affect their patients’ satisfaction.

In the national healthcare arena, research shows that organizations responsive to satisfaction issues reap significant financial gains, including greater profitability, a larger market share, increased rates of patient retention and referrals, and a reduced risk for malpractice suits6. With major reform pending within the insurance industry, experts expect that satisfaction data may soon be used by third-party payers to determine which providers will be included in their health plans and the reimbursement rates they will receive to compensate for their services7. Given these financial repercussions, several authors even speculate that non-responsive health organizations will eventually fold because of their inattention to satisfaction concerns6, 8, 9.

Despite the importance of satisfaction as a proxy for quality, the concept of patient satisfaction is not well defined. Upon examining 50 years of published patient satisfaction research across all specialties, one study has shown that 80–90% of the patients included in satisfaction studies are “satisfied.”10 Criticizing such studies, one author wrote, “Perhaps this type of study is adequate if the goal is to reassure the public that patients are largely contented. However, if our goal is to actually identify areas to improve care and the patient experience, then…they are insufficient.”10

This systematic review will examine the state of patient satisfaction research within Plastic Surgery. Given the premise of the outcomes movement is to emphasize outcomes from the patient’s perspective, we aim to examine research in which satisfaction levels were reported by the patients themselves, rather than by the provider. Specifically, our aims are to (1) characterize the studies and instruments being used to measure patient-reported satisfaction in Plastic Surgery publications, (2) define the standards of a good satisfaction study, and (3) discuss specific improvements for satisfaction studies that would enhance this area of research in Plastic Surgery.

Material and Methods

Search Criteria

In order to gain a current perspective on the state of satisfaction research, we performed a systematic review of patient satisfaction studies published within the field of plastic surgery within the last 15 years. Our goal was to identify studies that were categorized as plastic, reconstructive, or cosmetic surgery and have the measurement of patient satisfaction as at least one of their main themes. We searched the following four electronic databases: MEDLINE, Cochrane, International Science Institute’s Web of Science, and PyscInfo. Table 1 shows the details of the search for each database. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Search Terms

| Database | Search Terms and Boolean Operators | Fields Searched |

|---|---|---|

| Medline | (Patient Satisfaction OR Attitude to Health) AND (Plastic Surgery OR Cosmetic Techniques OR Reconstructive Surgical Procedures) | Keywords, exploded MeSH headings |

| Cochrane | (Patient Satisfaction OR Attitude to Health) AND (Plastic Surgery OR Cosmetic Techniques OR Reconstructive Surgical Procedures) | Keywords, exploded MeSH headings |

| PyscInfo | (Plastic Surgery OR Cosmetic Techniques OR Aesthetic Surgery OR Reconstructive Surgery OR Cosmetic Surgery OR Reconstructive Surgical Procedures) AND (Patient Satisfaction OR Acceptance of Healthcare OR Attitude to Health OR Patient Preferences OR Healthcare Acceptability) | Subject Fields |

| ISI Web of Science | (Patient Satisfaction) AND (Plastic Surgery OR Cosmetic Techniques OR Reconstructive Surgical Procedures) | Topic |

All searches were limited to articles in English, about humans, from peer-reviewed sources, and published between 1994–2009.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Each article gathered by the search was assessed for content. Articles were excluded from further review if they were written before 1994 or in a language other than English. Articles pertaining to procedures not considered to be of a plastic or reconstructive or cosmetic surgery nature were excluded. A list of the procedures of the articles excluded at this point is as follows: tattooing, laser hair removal, circumcision, genital mutilating procedures, body-piercing, cream application, skin treatments done by a dermatologist, and reconstructive procedures generally performed by an orthopedic, urology, or sports-medicine specialist. Of the remaining manuscripts, only those that specifically described how they measured the study participants’ satisfaction were included in the review. Many studies spuriously mentioned that their patients were “satisfied,” but described neither what exactly they were satisfied with nor how their satisfaction was measured. Because of this lack of detail, such articles were excluded from the review. Table 2 gives a summary of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Study Articles

| Characteristic | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| The Population | Surgical Patients receiving an explicitly plastic/reconstructive surgery procedure. | Patients receiving other operations and treatments. |

| The Interventions | An explicit and reproducible method used to measure patients’ satisfaction with their surgical experience. | Patient satisfaction not or only vaguely referenced. |

| Studies Included | English Language, published 1994 or later, any study design and/or article type. | Non-English Language, pre-1994 publications. |

Analysis of Study Characteristics

Two reviewers examined all articles retrieved by the search for adherence to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The reviewers jointly examined any articles in which they disagreed about the article’s inclusion/exclusion status and resolved the issue by consensus. The studies on the finalized inclusion list were read in entirety by both reviewers and appraised for the quality of the satisfaction measurement process. Specifically these studies were analyzed with respect to (1) the type of surgical procedure, (2) the domains of satisfaction that were measured, and (3) the characteristics of the measurement instruments. Finally, the year and location of the institutions where the study was done were recorded. This was done in order to assess how satisfaction research has changed over the last 15 years as well as to examine how satisfaction research in American institutions differs from that done outside of the United States.

Surgical Topic

The reviewers sorted the studies into the following 10 categories according to the type of surgical procedure being discussed: breast reconstruction, breast reduction, breast augmentation, genital surgery (cosmetic and reconstructive), hand surgery, cosmetic facial surgery, craniofacial surgery, liposuction/body contouring, other reconstructive surgeries, and an “all others” category. Our purpose was to determine the percentage of satisfaction studies in our review that were done within each sub-specialty and see if this percentage reflects the percentage of plastic surgery patients who are treated by that sub-specialty. In this way, we will determine which sub-specialties are proficient in undertaking satisfaction studies and which sub-specialties need to devote more research to the topic.

Domains of Satisfaction

In developing the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ), a widely used self-administered satisfaction survey for general patient populations, John Ware and his colleagues constructed a taxonomy for classifying the different domains of patient satisfaction with providers and medical services4. According to their review of satisfaction studies, all the features of care that influenced a patient’s satisfaction could be categorized into one of the following eight domains: interpersonal manner of provider, competence of provider, accessibility/convenience of care, finances, efficacy/outcomes of treatment, continuity of care, physical environment, and availability of care and resources.

We modified Ware’s taxonomy to make the domains more relevant to the Plastic Surgery experience by categorizing satisfaction issues into one of the following five domains: provider-related issues, aesthetic outcomes, functional outcomes, psychological outcomes, and an “all other issues” category.

Due to a scarcity of measurements about provider-related issues, we combined Ware’s domains of “interpersonal manner of provider” and “competence of provider” into one domain named “provider-related issues.” None of the studies in our review measured satisfaction regarding Ware’s domains of accessibility/convenience of care, finances, continuity of care, or physical environment. For this reason, we eliminated these domains from our review.

Additionally, because of the diversity of reasons for seeking treatment within Plastic Surgery and the variability of the outcomes, we extended the domain of “efficacy/outcomes” to three different domains that correspond to the different types of outcomes (aesthetic, functional, and psychological). Survey items were classified into the aesthetic outcomes domain if they inquired about patients’ opinions of the surgery’s impact on their appearance. This could refer to either how the patient felt about the appearance of the specific operated body part or to how the surgery impacted their overall appearance. Items were placed into the functional outcomes domain if they referred to patients’ opinions of how the surgery impacted the functional level of the operated body part. This included inquiries about pain and sensitivity levels, as well as assessments of strength, range of motion, and capabilities to do specific tasks. The psychological outcomes domains contained survey items that refer to the patients’ assessments of how their surgery impacted their self-esteem, self-confidence, or other aspects of their mental health.

In our review, few studies included items that addressed issues in the domain of availability of care and resources domain. Several studies inquired about patients’ satisfaction with pre-surgery educational resources or rehabilitation support systems made available to them. Other studies asked patients’ to assess how other areas of their life have been impacted by their procedure, including their relationships and their libido. Because these items do not clearly fall into one of Ware’s categories, we created an “all others” categories. The issues belonging to this category were not measured frequently.

After categorizing the items that were measured, we recorded how frequently patient satisfaction was measured within each particular domain. Our aim is to determine which domains of satisfaction are being measured and how often. Because satisfaction has a multi-dimensional construct, it is important that all the different aspects of satisfaction are measured, rather than only measuring the patient’s “overall” satisfaction. Through measuring the variety of aspects of satisfaction, physicians are able to discover the specific areas that require attention and thus improvements can be targeted more effectively.

Satisfaction Measurement Instrument

Each study was placed into one of the following categories based on the characteristics of the measurement tool and its creation process: (1) an ad-hoc questionnaire, (2) a standardized generic questionnaire that is not specific to the procedure described in the article, or (3) a well-developed and procedure-specific instrument. This was done to examine the state of the questionnaires being used in satisfaction research. An outcomes questionnaire should be reliable, valid and responsive, properties which are tested in a formal development process. In the 1990’s the Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) of the Medical Outcomes Trust established a rigorous system for assessing patient reported outcome instruments11. Based on their system, Cano et al. constructed a process for developing quality instruments that meet this criteria12. This process consists of carefully planned and executed stages of item generation, pilot testing, and psychometric evaluation. In the item generation stage, a comprehensive literature review is conducted to determine all the important topics that are relevant to the particular type of surgery and patient population. Then, drawing from these topics, the survey’s preliminary questions are developed through focus group discussions with both experts and patients. After the preliminary questions have been created, the survey is administered to several groups of patients (both pre-and post-operatively) to test the levels of responsiveness, test-retest reproducibility, and correlations between items. After these pilot tests, the psychometric properties of the survey are evaluated using the SAC’s system. After the necessary modifications are made, the survey is validated and useful for outcomes research projects.

Results

Study Retrieval

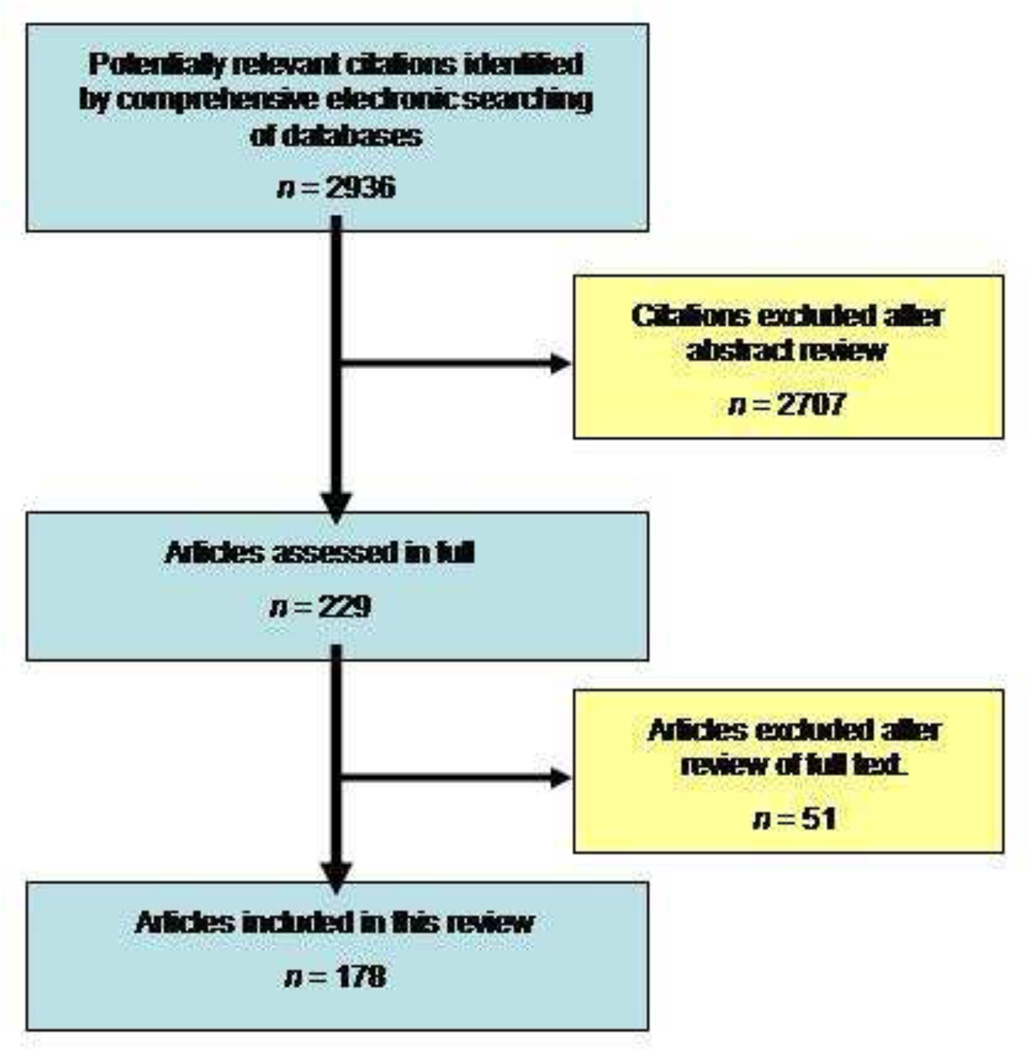

The database searches yielded a total of 2,936 articles. After a comprehensive review process, 178 articles were included in the final review. Interested readers can contact the senior author for an appendix with the reference information for the articles included in the review. A selection flow chart is presented in Figure 1. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Review Process

Results of Analysis of Study Characteristics

Surgical Topics

Breast reconstruction constituted the largest group in our review, with 71 articles or 40% of all studies in the review. With the exception of Cosmetic Facial Surgery, which had 36 studies and represented 20% of the entire review, the other surgical topics were significantly less represented. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Distribution of Satisfaction Studies

| Type of Surgery | % of All Studies (# of studies) |

|---|---|

| Breast Reconstruction | 40% (71) |

| Cosmetic Facial Surgery | 20% (36) |

| Breast Reduction | 10% (18) |

| Craniofacial Surgery | 8% (14) |

| Breast Augmentation | 8% ( 14) |

| Liposuction/Body Contouring | 5% (9) |

| Other Reconstructive Surgeries | 3% (6) |

| Genital Surgery | 3% (5) |

| Hand Surgery | 2% (4) |

| All others | 2% ( 3) |

Number of reviews does not add up to 178 because 1 review included the surgical topics of Breast Reconstruction and Breast Reduction and 1 review included the surgical topics of Breast Reconstruction and Breast Augmentation.

Domains of Satisfaction

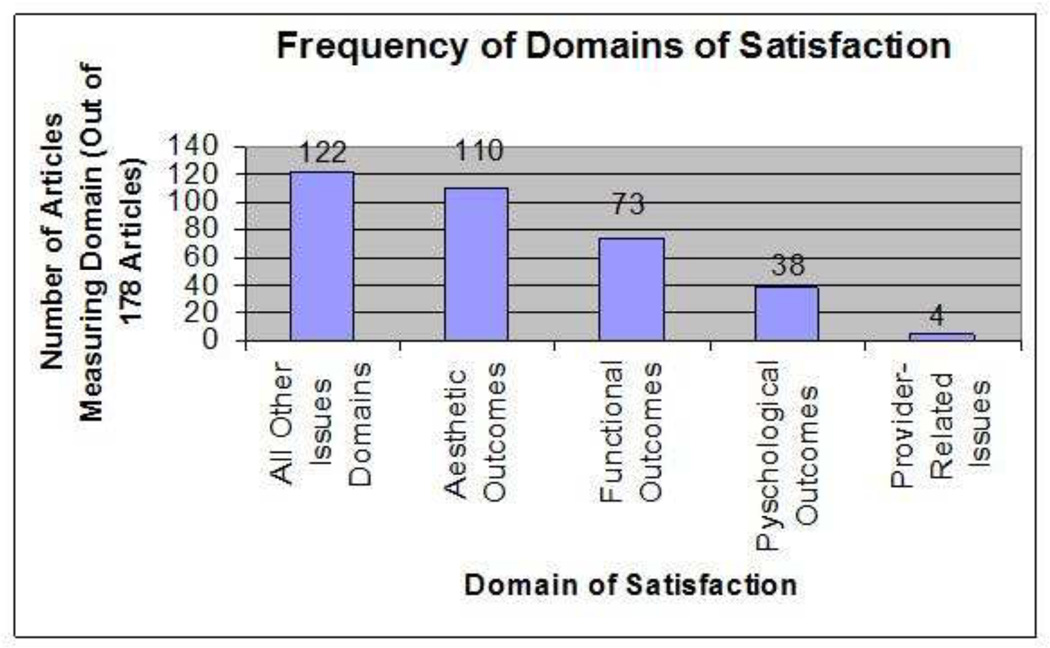

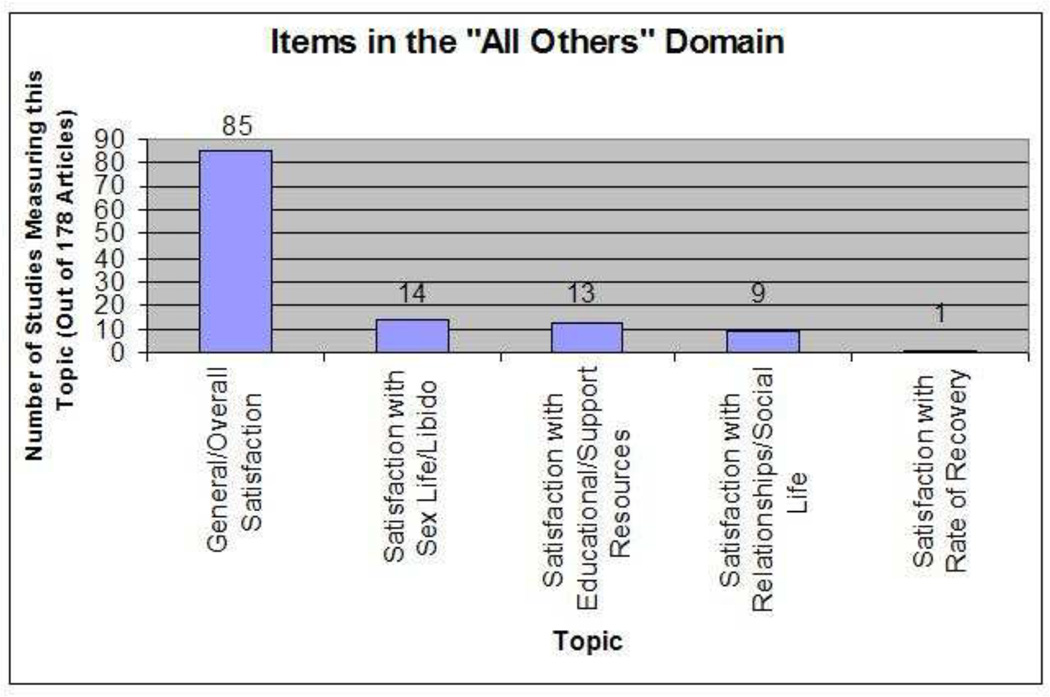

Ninety-five studies (representing 53% of the review) measured only one or two domains of satisfaction. Fifty-seven studies (32%) measured three domains and only 26 studies (15%) measured 4 domains. One hundred and ten of the articles (62%) measured patient satisfaction with issues that were categorized into the “aesthetic outcomes” domain. Of the 122 studies that measured an aspect of satisfaction in the “all others” domain, 85 were only inquiring about patients’ “general” or “overall” satisfaction. The satisfaction domains of functional and psychological outcomes were each measured by 73 studies (41%) and 38 studies (21%), respectively. (Figure 2) (Figure 3)

Figure 2.

Bar Graph of the Domains of Satisfaction

Figure 3.

Bar Graph of “All Other” Domain Issues

Satisfaction Measurement Instrument

One hundred twenty-one (68%) studies used only ad-hoc questionnaires to evaluate their patients’ satisfaction. This category represents those instruments that were created by the authors without following a formal development process. On the other hand, 21 studies (12%) used only validated questionnaires that were developed following formal guidelines and targeted specific patient populations according to the plastic surgery procedure they received. Eighteen studies (10%) used only generic, non-surgery specific questionnaires. Eighteen of the studies in our review (10%) used a combination of the three types of surveys. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Quality of Measurement Tools

| Type of Measurement Tool | ∼ % of Studies Utilizing This Type (# of Studies) |

|---|---|

| Ad-hoc Questionnaires Only | 68% (121) |

| Generic Questionnaires Only | 10% (18) |

| Well-developed, Procedure-specific Questionnaires Only | 12% (21) |

| Combination of Ad-hoc and Generic Questionnaires | 6% (11) |

| Combination of Ad-hoc and Well-developed, Procedure-specific Questionnaires | 1.5% (3) |

| Combination of Generic and Well- developed, Procedure-specific Questionnaires | 1.5% (3) |

| Combination of Ad-hoc, Generic, and Well-developed, Procedure-specific Questionnaires | 0.5% (1) |

National Versus International Satisfaction Research

Seventy-nine of the satisfaction studies were performed by U.S. institutions, constituting 44% of the total studies in our review. Thus, the other 99 studies (56%) were done by international institutions. Our analysis revealed that both U.S. and international satisfaction research efforts are limited by the same problems. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Comparison of National and International Studies

| Location | United States | International |

|---|---|---|

| # of Studies | 79 | 99 |

| % of Studies That Are Breast Related | 47 | 65 |

| % of Studies Using Only Ad-hoc Questionnaires | 75 | 62 |

| % of Studies Examining 3 Or More Domains | 43 | 51 |

Our review indicates that U.S. satisfaction studies are more diverse in surgical topic than International satisfaction studies, but rely more on ad-hoc instruments and tend to measure fewer domains of satisfaction.

Research Trends Over Time

To examine how Plastic Surgery satisfaction research has changed over the past decade and a half, we sorted the studies in our review into 3 groups based on their year of publication. The first group contained studies published from 1994–1998, the second group studies published from 1999–2003, and the third group studies from 2004–2009. The results of this exercise show that Plastic Surgery patient satisfaction research is moving in the right direction, as both the number and quality of satisfaction studies steadily increased during the years of our review. (Table 6)

Table 6.

Satisfaction Research has Improved Over Time

| Year of Publication | 1994–1998 | 1999–2003 | 2004–2009 |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of Studies | 13 | 55 | 110 |

| % of Studies That Are Breast Related | 77 | 60 | 53 |

| % of Studies Using Only Ad-hoc Questionnaires | 85 | 67 | 66 |

| % of Studies Examining 3 or More Domains | 15 | 28 | 36 |

Since 1994 (the first year of literature reviewed), the number of satisfaction studies has greatly increased. Additionally, the diversity of surgical topics has increased, as well as the number of studies in non-breast sub-specialties and the number of domains being measured.

Discussion

Over the past two decades, the Outcomes Movement has revolutionized the principles and guidelines of clinical investigations by emphasizing the necessity of gathering patient-reported outcomes. As evidenced by the large number of studies gleaned by the search criteria for this review, much progress has been made within Plastic Surgery regarding the development of outcome instruments based on the patient’s perspective. Substantial work remains, however, in further refining these instruments for use in Plastic Surgery.

The results of this systematic review revealed three areas where improvement in patient satisfaction research can be made: (1) increasing the number of satisfaction studies done within non-breast related Plastic Surgery topics, (2) measuring multiple dimensions of satisfaction rather than only one or two, and (3) using well-developed, surgery-specific questionnaires instead of generic and ad-hoc questionnaires.

A large proportion of the satisfaction studies (58%) were focused on breast surgery, whereas satisfaction outcomes have received less attention in other plastic surgery subspecialties. More research must be done by all Plastic Surgery sub-specialties to incorporate the satisfaction outcomes as part of their clinical studies. This systematic review also revealed that more dimensions of patient satisfaction should be surveyed in future research. The literature shows that a patient’s satisfaction depends on a number of different aspects of the experience, and with 53% of the studies in our systematic review only inquiring about one or two aspects of their satisfaction, a large spectrum of satisfaction outcomes is left unexamined. Knowing patients’ levels of satisfaction with the different parts of their treatment experience should promote improvement efforts with specific aspects of care. Measuring general satisfaction alone is not specific enough to point out the areas of a practice that need improvement. The usefulness of a satisfaction survey hinges on its ability to point out those areas where improvement can be made.

Finally, the results show that 121 (68%) of the reviewed ‘satisfaction’ studies apply only ad-hoc questionnaires. Because of the myriad of different methods used in these studies to gather, score, and analyze the data, the results from ad hoc questionnaires may not be reliable, valid and responsive. Although these ad-hoc questionnaires may have face validity, unless they are developed systematically and tested for psychometrical properties, their scientific quality is uncertain. The use of generic questionnaires may be more expedient and is applied in 18% of the studies in our review. But these questionnaires do not target specific conditions and certain populations, which affects the discriminant validity of these questionnaires. Thus both ad-hoc and generic tools are inadequate for measuring satisfaction related to the effects of a specific procedure. We propose that satisfaction instruments have the following characteristics: (1) that they are procedure-specific, (2) that they have undergone a formal development process, (3) that they are reliable, valid, and responsive, and (4) that they consider the multiple domains of satisfaction.

The need for satisfaction-related outcomes instruments is great. Regardless of the type of delivery and reimbursement systems that will result from the imminent reforms in the health industry, experts agree that patient-centered care will play an increased role 13–16. A number of government agencies, industry regulators, and insurance companies are calling for physicians to report their patients’ outcomes13, 14. Patient Satisfaction data are included in the list of outcomes that insurance companies and care providers will need to report15.

Some of the commercial and government payors that offer Pay-for-Performance reimbursement programs, including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Blue Cross of California, are already using patient satisfaction reports as one of the metrics to determine the quality of care delivered by their plan’s providers. In these programs, physicians report a set of specialty-specific performance measures, developed by the payor, for each patient they see. Some payors offer physicians financial rewards if their patients’ outcome measures meet certain benchmarks. For example, physicians who participate in Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) are eligible to receive a bonus of 1.5% of their total fee schedule charge if they report the requisite outcome measures for at least 80% of their Medicare patients. Several academic institutions, like the Emory Clinic and Southwestern Vermont Medical Center, have even linked faculty physicians’ salaries and bonuses to their patients’ outcomes data, including satisfaction data15.

The ultimate goal of outcome reporting programs is to make the information available to the public13, 14, 16. This is especially pertinent for Plastic Surgery, because patients seeking treatment often are able to “shop around” before choosing a surgeon. These patients will be able to compare outcomes data from different surgeons in making their decisions about which treatment to seek and which provider to see. Making satisfaction outcomes data available to everyone will foster competition between both providers and health systems, thereby leveraging market forces to bring down the costs of care and give patients the best quality of care for their money. Creating this sort of competition is the cornerstone of the reforms being pushed for by President Obama and many congressmen17. In the current era of quality assurance and continual improvement, Plastic Surgery can demonstrate the value of its services by developing better scientific metrics to evaluate the patients’ perceptions of surgical procedures and their experiences interfacing with this specialty.

Table 7.

Names and Frequencies of the Generic Instruments Used in the Studies of Our Review

| Name of Instrument | # of Studies Using This Instrument |

|---|---|

| Short-Form 36 | 11 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 4 |

| Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale | 2 |

| Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) | 2 |

| Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZ) | 2 |

| Body Cathexis Scale | 1 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 1 |

| QLQ-C30 | 1 |

| Multi-Dimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire | 1 |

| Body Image Visual Analogue Scale | 1 |

| Health Utilities Index Mark 2 | 1 |

| Health Utilities Index Mark 3 | 1 |

| Social Adaption Self-evaluative Scale | 1 |

| QL-Index | 1 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Ham-A) | 1 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Ham-D) | 1 |

| Childhood Experience Questionnaire | 1 |

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

References

- 1.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware JEJ. How to Survey Patient Satisfaction. Drug Intelligence and Clinical Pharmacy. 1981;15:892–899. doi: 10.1177/106002808101501107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder-Pelz S. Toward a Theory of Patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ware JEJ. Defining and Measuring Patient Satisfaction with Medical Care. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1983;6:247–263. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware JEJ, Davies-Avery A, Steward A. The measurement and meaning of patient satisfaction. Health Med Care Serv Rev. 1978;1:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fottler MD, Ford RC, Bach SA. Measuring Patient Satisfaction in Healthcare Organizations: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Best Practices and Benchmarking in Healthcare. 1997;2(6):227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KC, Hamill JB, Kim HM, Walters MR, Wilkins EG. Predictors of patient satisfaction in an outpatient plastic surgery clinic. Ann Plast Surg. 1999 Jan;42(1):56–60. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otani K. Patient Satisfaction: Focusing on "Excellent". Journal of Healthcare Management. 2009;54:93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund CM. Benchmarking Patient Satisfaction. Best Practices and Benchmarking in Healthcare. 1996;1(4):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin NJ. Opinions: Patient Satisfaction Surveys: Another View. Healthcare Quarterly. 2007;10(3):8. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2007.18916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohr K. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano S, Browne J, Lamping D. The Patient Outcomes of Surgery-Hand/Arm (POS-Hand/Arm): A new patient-based outcome measure. J Hand Surgery (Br.) 2004;29:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal MB. What works in market-oriented health policy? N Engl J Med. 2009 May 21;360(21):2157–2160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903166. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter ME. A Strategy for Health Care Reform-Toward a Value-Based System. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul 9;361(2):109–112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904131. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Impact of Patient Satisfaction on Pay-For-Performance in Medical Practices. Press Ganey; 2008. [Accessed July 28, 2009]. Updated Last Updated Date. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray K, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development: Incorporating Patient Preferences. JAMA. 2008;300(4):436–438. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacker J. Healthy Competition-The Why and How of "Public-Plan Choice". N Engl J Med. 2009 May 28;360(22):2269–2271. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903210. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]