Abstract

The main culprit in the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is the generation of high level of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In this study, we report a novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategy for I/R injury based on H2O2-activatable copolyoxalate nanoparticles using a murine model of hind limb I/R injury. The nanoparticles are composed of hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HBA)-incorporating copolyoxalate (HPOX) that, in the presence of H2O2, degrades completely into three known and safe compounds, cyclohexanedimethanol, HBA and CO2. HPOX effectively scavenges H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner and hydrolyzes to release HBA which exerts intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities both in vitro and in vivo models of hind limb I/R. HPOX nanoparticles loaded with fluorophore effectively and robustly image H2O2 generated in hind limb I/R injury, demonstrating their potential for bioimaging of H2O2-associated diseases. Furthermore, HPOX nanoparticles loaded with anti-apoptotic drug effectively release the drug payload after I/R injury, exhibiting their effectiveness for a targeted drug delivery system for I/R injury. We anticipate that multifunctional HPOX nanoparticles have great potential as H2O2 imaging agents, therapeutics and drug delivery systems for H2O2-associated diseases.

Keywords: Theranostics, Bioimaging, Drug delivery, Polymer, Hydrogen peroxide

1. Introduction

I/R injury occurs in a variety of clinical conditions, such as coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and stroke [1–5]. Reperfusion of blood flow to previously ischemic tissues is accompanied by generation of large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which overwhelm cellular defenses and damage normal cellular functions. When oxygen is resupplied during reperfusion, NADPH oxidases are known to generate a large amount of toxic ROS which include H2O2, superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, hypochlorous acid and nitric oxide-derived peroxynitrite [6]. In particular, H2O2, the most abundant form of the ROS produced during I/R, induces oxidative stress and triggers apoptosis, further exacerbating initial tissue damages. Despite its essential role in cellular signaling in living organisms, overproduced H2O2 is known to be a major source of oxidative stress and serves as a precursor of highly reactive ROS such as hydroxyl radical, peroxinitrite and hydrochlorite [7]. Therefore, targeting H2O2 as a diagnostic marker as well as a therapeutic target for I/R injury has tremendous potential.

Over the past decades, tremendous efforts have been made in the development of biodegradable polymers for drug delivery systems which can enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of conventional drugs and improve patient compliance/convenience, while reducing their detrimental side effects and required dose. To date, the most thoroughly investigated biodegradable polymers have been members of polyesters, such as poly(lactic acid), poly(glycolic acid) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [8,9]. In general, therapeutic drugs are physically admixed within the matrix and released during the degradation of the polymer matrix. The polymeric drug carriers could provide considerable benefits such as enhanced therapeutic effects, prolonged bioactivity, controlled release rate and decreased administration frequency/dose. However, a drawback of these degradable polymers is that the high concentration of acidic degradation products at a localized site causes inflammatory responses. Moreover, nanoparticulate drug carriers have limited drug loading which prevents them from achieving the full drug delivery potential. In this regard, there has been increasing interest in the development of new polymeric drug carriers that have a high content of deliverable drugs and induce little to no inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. One of the approaches to fulfill these criteria involves the direct incorporation of bioactive molecules into the backbone of biodegradable polymers, pioneered by Uhrich [10,11].

Previously, we developed fully biodegradable polyoxalate copolymer (HPOX) which chemically incorporates naturally occurring bioactive hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HBA) in the backbone of polymers [12,13]. HBA is one of phenolic compounds found in diverse plants and is a major active pharmaceutical ingredient in Gastrodia elata Blume, which has been used as an herbal agent [14]. HPOX was designed to covalently incorporate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory HBA in its backbone, not attached to the side groups and release HBA during its hydrolytic degradation. Another unique property of HPOX is its ability to react with H2O2 to perform peroxalate chemiluminescence reaction in the presence of fluorescent compounds. Previously, nanoparticles based on polyoxalate were developed which could image H2O2 produced in a peritoneal cavity in mice during lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation [15]. However, the polyoxalate was unsuitable for formulation into solid nanoparticles due to its instability under aqueous conditions, limiting its applications in both bioimaging and drug delivery.

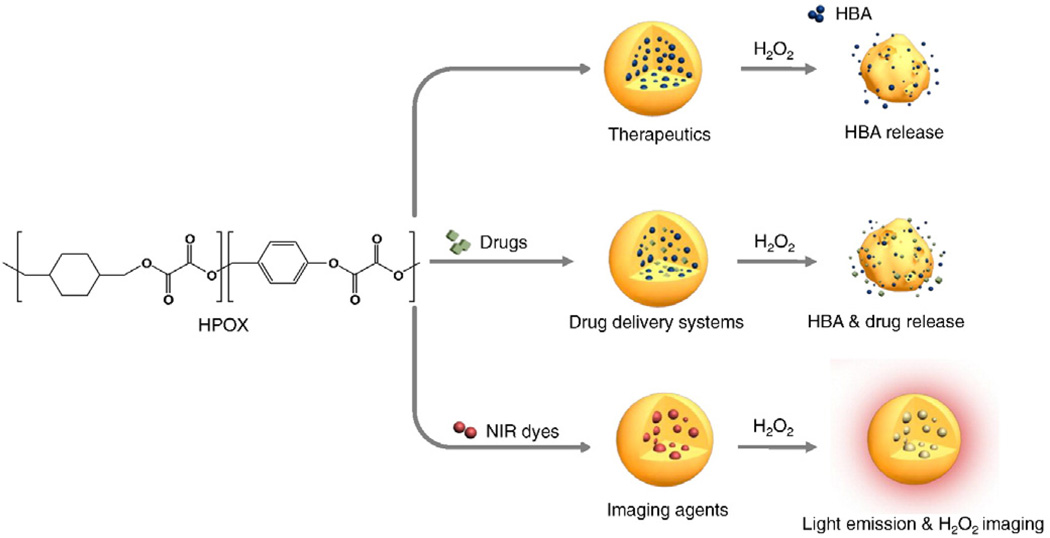

In this paper, we report molecularly engineered solid HPOX nanoparticles with enhanced stability and high specificity for H2O2, thus allowing physiological bioimaging and therapy for I/R injury. We used a mouse model of hind limb I/R to evaluate the potential of multifunctional HPOX nanoparticles as H2O2 imaging agents and therapeutics for H2O2-associated inflammatory diseases. In addition, the potential of HPOX nanoparticles as site directed drug delivery systems for I/R injury was investigated using an anti-apoptotic agent, 4-amino-1,8-napthalimide (4-AN) as a model drug. Here, we present multifunctional H2O2-activatable nanoparticles that are able to image H2O2 in vivo, possess intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and capable of site directed drug delivery for the treatment of I/R injury (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multifunctional H2O2-activatable nanoparticles as a novel strategy for bioimaging and therapy. HPOX nanoparticles are able to serve as H2O2 imaging agents, therapeutics and site-directed drug delivery systems for I/R injury.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of HPOX

All chemicals and solvents were of American Chemical Society grade or HPLC purity and were used as received. HPOX was synthesized using cyclohexanedimethanol, 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol and oxalyl chloride. Briefly, 1,4-cyclohexanedimethanol (21.96 mmol) and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (5.49 mmol) were dissolved in 20 mL of dry tetrahydrofuran (THF) and triethylamine (60 mmol) was added dropwise to the solution under nitrogen at 4 °C. Polymerization was initiated by adding oxalyl chloride (27.45 mmol) in 25 mL of dry THF to the reaction solution at 4 °C, and the reaction mixture was kept under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature for 6 h. Polymers were obtained through extraction using dichloromethane (DCM), followed by precipitation in cold hexane. The chemical structure of polymers was identified with a 400 MHz 1H NMR spectrometer (JNM-EX400 JEOL), and the molecular weight was determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Futecs, Korea) to be approximately 20 kDa with a mean polydispersity of 1.8.

2.2. Nanoparticle preparation and characterization

HPOX nanoparticles were generated using an emulsion/solvent evaporation method. In brief, 100 mg of HPOX dissolved in 1 mL of DCM was added to 5 mL of 10 (w/v)% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution and homogenized using a sonicator and homogenizer to form a fine oil/water emulsion. The emulsion was transferred to a 20 mL PVA (1 w/v%) solution and homogenized for 1 min. The remaining solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator. The particles were then centrifuged and washed with de-ionized water three times to remove residual PVA. The suspension was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized to produce free-flowing particles. To develop HPOX nanoparticles loaded with rubrene or 4-AN, 5 mg of rubrene or 10 mg of 4-AN was dissolved in 100 µL of DCM or dimethylsulfoxide, respectively. The procedures for particle formulation were the same as for empty HPOX nanoparticle formulation. For comparison, PLGA (MW 30 kDa) was also formulated into nanoparticles using the same procedure for HPOX. It was determined that 1 mg of PLGA and HPOX nanoparticles contained ~95 µg and~75 µg of 4-AN, respectively.

2.3. Release kinetics of 4-AN

HPOX or PLGA nanoparticles (5 mg) loaded with 4-AN were dispersed in 20 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with or without 100 µM H2O2 and incubated under continuous stirring at 37 °C. At appropriate time points, the suspension was centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 30 s. A 2 mL aliquot of supernatant was taken and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS. The concentration of 4-ANin the supernatant was measured using a UV-spectrometer (S-3100, Scinco, Korea) and the release kinetic was determined by comparing the concentrations of 4-AN standard solutions.

2.4. Detection and scavenging of H2O2

HPOX nanoparticles were suspended in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4 to give a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Various amounts of the H2O2 solution (1 mM in PBS, 0.1 M) were added to the nanoparticle suspensions, and the chemiluminescence intensity was measured with a luminometer (Femtomaster FB12, Zylux Corporation, Huntsville, AL) with a 10 sec acquisition time. The chemiluminescence emission spectra were obtained in the presence or absence of H2O2 using a spectrofluorometer (RF-6500-PC, Shimadzu, Japan). The ability of HPOX nanoparticles to scavenge H2O2 was evaluated by measuring the H2O2 concentration. HPOX nanoparticles (0.5 or 1 mg) were added into 1 mL of H2O2 solution (10 µM). The H2O2 solutions were incubated at 37 °C under mechanical stirring for 24 h. After short centrifugation at 1000 ×g, the H2O2 concentration of the supernatant was measured using the Amplex Red Assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.5. Flow cytometry

RAW 264.7 cells (1 × 106 cells) were seeded in a glass bottom dish (MatTek Corp. Ashland,MA) and cultured for 24 h prior to the experiment. Cells cultured were treated with HBA or HPOX nanoparticles for 12 h and then incubated with 2 µg of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) for 4 h to induce intracellular ROS generation. Dichlorofluorescin-diacetate (DCFH-DA) was added to each dish to observe ROS generation. Cells were also incubated with 100 µM of H2O2 to induce apoptosis and treated with Annexin-V labeled with FITC for 15 min. Flow cytometry was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACScan (Mountain View, CA).

2.6. Animal surgeries

For biocompatibility study, we administered HPOX by intraperitoneal injection on a daily basis. The subject size was 4/group for vehicle and HPOX groups. After 7 days of injections, blood of each mouse was collected and centrifuged (2000 ×g for 10 min) to separate serum. Creatinine and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels were measured within 24 h using an IDEXX Catalyst Dx* Chemistry Analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Maine, USA). The organs were removed and embedded in paraffin. Serial paraffin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. I/R surgeries were performed in 15–16 week old male FVB mice (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) as described previously [16]. After mice were anesthetized, femoral artery was identified and tied around a specialized 30G-catheter with a 7-0 silk suture. The animal remained under anesthesia for a specified duration of ischemia. Reperfusion was achieved by cutting the suture and reestablishing arterial blood flow. Sham operated mice underwent the same procedure without femoral artery occlusion/reperfusion. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed at 2 days for biochemical/molecular studies, and at 2 weeks for histological analysis. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

2.7. Bioluminescence imaging

In vivo bioluminescence imaging was carried out with a Xenogen IVIS 50 imaging system (Caliper LS, Hopkinton, MA). Images and measurements of bioluminescent signals were acquired and analyzed using Living Image software. The animals were anesthetized using 1–3% isoflurane, and placed onto the warmed stage inside the camera box. The animals received continuous exposure to 1–2% isoflurane to sustain sedation during imaging. Image acquisition times were 1–3 min. The region of interest (ROI) that was defined manually over the whole body was quantified as photons/second (ph/s) using the software.

2.8. Assays for caspase-3 and PARP-1 activities

Caspase-3 activities were measured using synthetic caspase substrate AcDEVD-pNa. Release of pNa was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm by a spectrometer, and adjusted to the background. PARP activity was measured with an ELISA based, PARP Universal Colorimetric Assay Kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

2.9. Immunohistochemistry

Immunofluorescent staining was performed as described on frozen sections of the muscle tissues in the ischemic area 24 h after I/R surgery. Apoptosis was quantified using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. We used 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to stain nuclei. The amount of apoptosis was expressed as the number of TUNEL positive nuclei (TUNEL+) as a proportion of the total number of all nuclei (N). At least 10 high power fields (~2000 nuclei/field) were analyzed.

2.10. Statistical analyses

Calculations and statistics were performed using GraphPad 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical analysis was carried out using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni's tests for post hoc differences between group means. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of HPOX nanoparticles

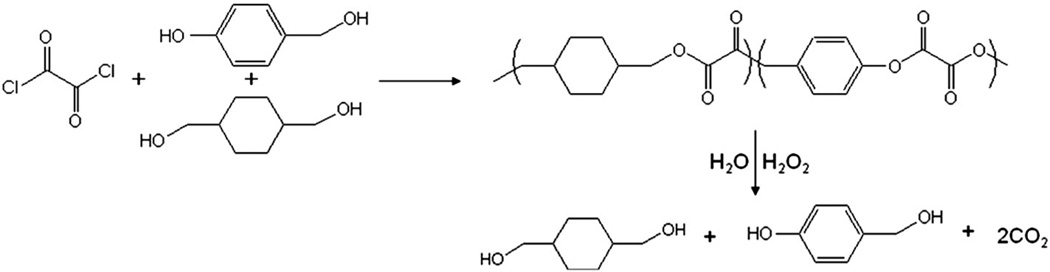

The nanoparticles were composed of HBA-incorporating copolyoxalate (HPOX), which is a recently developed H2O2-responsive polymer (Fig. 2) [12]. HPOX has great potential for treating various H2O2-associated and inflammatory diseases because, in the presence of H2O2, it is designed to degrade completely into cyclohexanedimethanol (a FDA approved food additive), HBA (an antioxidant and antiinflammatory agent often found in herbal products and a powerful scavenger of free radicals), and carbon dioxide. Despite its fast hydrolysis with a half-life of ~14 h, due to its hydrophobic nature under physiological condition, we were able to formulate nanoparticles using an emulsion/solvent-evaporation method and lyophilize them, yielding solid nanoparticles.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structure, synthesis and degradation of HPOX nanoparticles. The chemical structure of polymers was identified with a 400 MHz 1H NMR spectrometer (JNM-EX400 JEOL). 1H NMR in deuterated chloroform on a 400 MHz spectrometer: 7.2–7.3 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.5–7.6 (m, 2H, Ar), 5.3 (m, 2H OCH2-PhO), 4.1–4.3 (m, 4H, COOCH2CH), 1.8–2.0 (m, 2H, C(CH2)3HO), 1.0–1.8 (m, 8H, cyclic CH2).

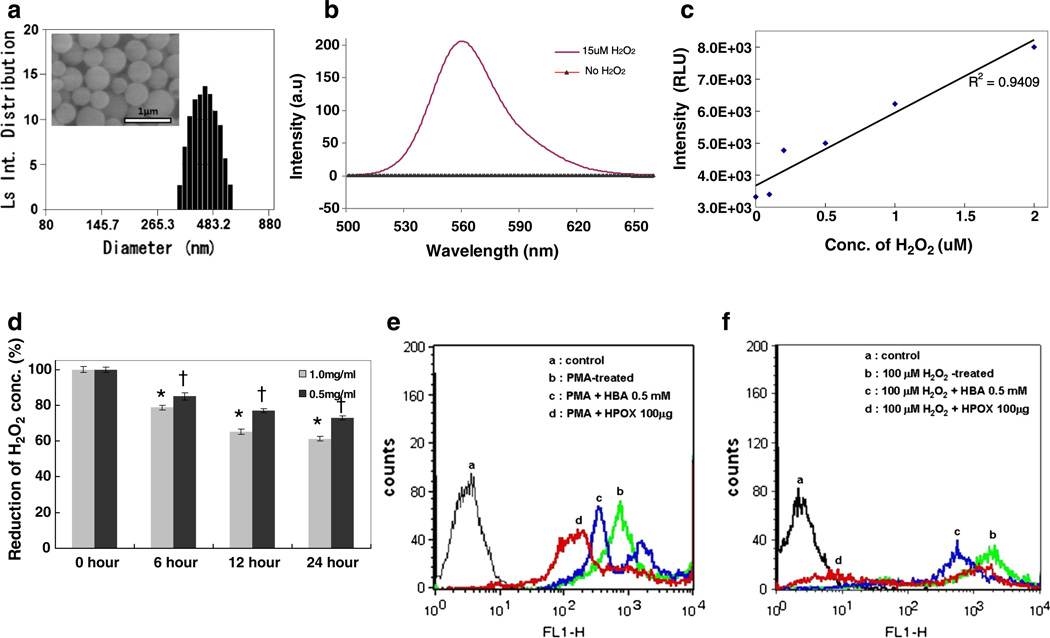

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed that the nanoparticles are smooth and round spheres with an average diameter of ~450 nm (Fig. 3a). Encapsulation of fluorescent dyes or anti-apoptotic drugs into the particles shows no significant effects on the particle shape and size (data not shown). HPOX possesses the peroxalate ester linkages in its backbone and therefore is able to perform a three component chemiluminescence reaction between peroxalate ester, H2O2, and fluorophore. We first investigated the chemiluminescence properties of HPOX nanoparticles loaded with rubrene (Rb) as a fluorophore. As shown in Fig. 3b, the addition of H2O2 to the suspension of rubrene-loaded HPOX nanoparticles (HPOX/ Rb) instantaneously initiated chemiluminescence reactions to produce high energy intermediate dioxetanedione that chemically excites Rb, leading to the generation of strong light emission at 565 nm [17,18]. The nanoparticles showed no light emission without H2O2. HPOX/Rb showed a linear correlation between chemiluminescence intensity and H2O2 concentration within a range of 0–2 µM and they could detect H2O2 as low as ~250 nM (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Specificity and sensitivity of HPOX nanoparticles to H2O2 in vitro. (a) A representative DLS image of empty HPOX nanoparticles. Inset is a representative SEM image. (b) Chemiluminescence emission of rubrene-loaded HPOX nanoparticles in the presence/absence of H2O2. (c) Sensitivity of HPOX to different concentrations of H2O2. (d) Scavenging of H2O2 by HPOX nanoparticles. *P < 0.05 vs 0 h control, †P < 0.05 vs 1.0 mg/mL groups. n = 4/group. (e) Inhibition of ROS generation by HPOX nanoparticles in PMA-stimulated macrophages. (f) Anti-apoptotic property of HPOX nanoparticles in H2O2-stimulated macrophages.

We also hypothesized that HPOX nanoparticles could scavenge H2O2 because peroxalate ester linkages in the HPOX backbone react with H2O2 and decompose into carbon dioxide. We found that HPOX nanoparticles scavenge H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner, with remarkable (~40%) reduction at the concentration of 1 mg/mL in 10 µM of H2O2 solution (Fig. 3d).We also investigated the antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of HPOX nanoparticles in vitro (Fig. 3e). RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with PMA to induce ROS generation and the generation of ROS in cells was observed using DCFH-DA as a probe for intracellular ROS. PMA-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells generated a large amount of ROS, evidenced by strong DCFH-DA fluorescence. Free HBA (0.5 mM) showed inhibitory effects on ROS generation. However, treatment of HPOX nanoparticles significantly suppressed the ROS generation in PMA-stimulated cells more effectively than free HBA.

A high concentration of H2O2 is known to induce apoptosis, which is highly associated with numerous pathological conditions such as myocardial/reperfusion injury. We therefore studied the potential of HPOX nanoparticles to inhibit H2O2-mediated apoptotic cell death. H2O2-mediated apoptosis was analyzed using Annexin V-FITC by flow cytometry. Free HBA exhibited a moderate anti-apoptotic activity of HBA, evidenced by a leftward shift of Annexin V-FITC fluorescence. However, HPOX nanoparticles exhibited a stronger anti-apoptotic activity than free HBA (Fig. 3f). The stronger antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activity of HPOX is likely attributed to the combined effects of H2O2 scavenging activity and its intrinsic antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic activity of released HBA.

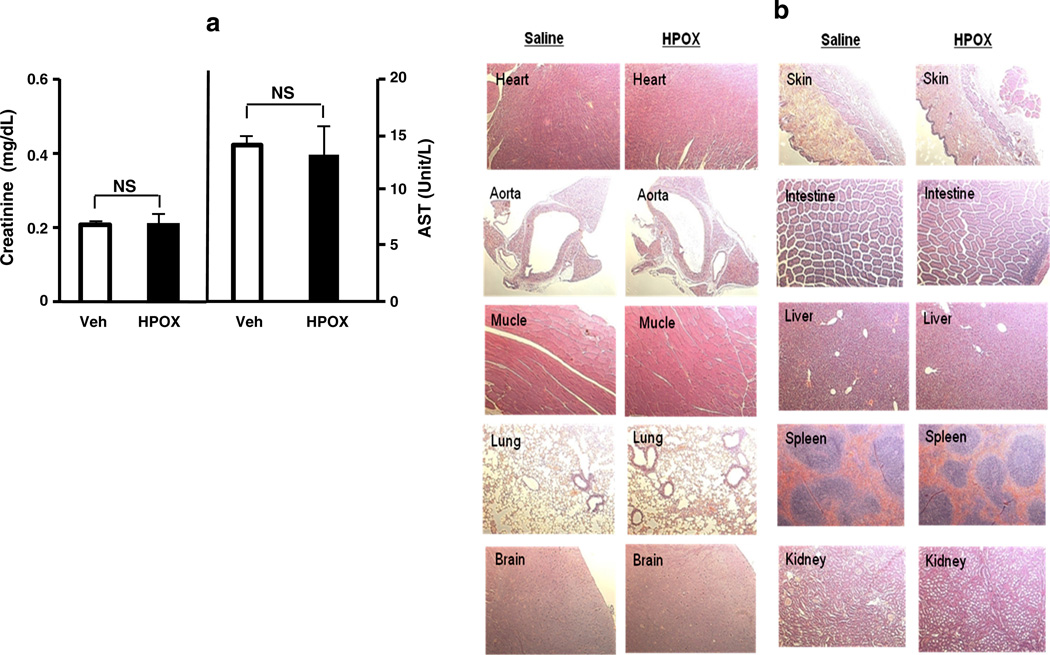

3.2. Biocompatibility of HPOX nanoparticles

To determine the potential cumulative toxic effects of HPOX, we administered HPOX daily for 7 days in mice. Serum tests for renal function and hepatic function showed no significant abnormalities after 7 days (Fig. 4a). In addition, there was no significant histological evidence of accumulated toxicity in the different organs associated with administration of HPOX for 7 days (Fig. 4b). These observations demonstrate that HPOX nanoparticles have no or little cumulative toxicity in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Biocompatibility of HPOX nanoparticles after daily intraperitoneal administration for 7 days. (a) Creatinine and aspartate transaminase (AST) level. (b) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)—stained tissue sections of different organs. HPOX at 50 µg/day was administered for 7 days. n = 4/group.

3.3. Imaging of H2O2 using chemiluminescent HPOX nanoparticles

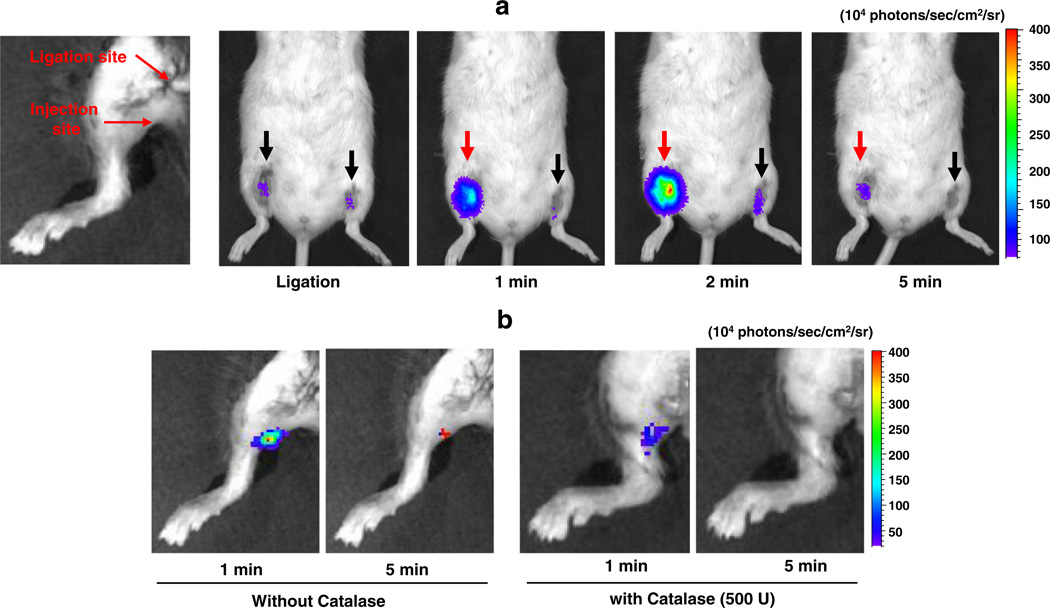

The bioimaging potential of HPOX was assessed by determining whether HPOX/Rb could image the endogenous level of H2O2. We used a mouse hind limb I/R model with 1 h of ischemia followed by reperfusion. HPOX/Rb was directly injected distal to the ligated site 30 min before the reperfusion, and the chemiluminescent light emission imaging was performed on a Xenogen IVIS 50 small animal imaging system. HPOX/Rb showed a robust and significant activation to generate light emission within 1 min of reperfusion, peaking at 2 min.

Chemiluminescent light emission completely disappeared after 10 min of reperfusion (Fig. 5a). Additionally, to confirm whether activation of HPOX/Rb is specific for H2O2, H2O2-degrading enzyme, catalase was injected with HPOX/Rb to determine whether nanoparticle activation could occur in the absence of H2O2 production. Catalase coadministration resulted in significant inhibition of HPOX activation and reduced light emission (Fig. 5b). Based on these data, we conclude that HPOX nanoparticles are able to detect endogenously overproduced H2O2with excellent sensitivity and specificity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the imaging of endogenously overproduced H2O2 in I/R injury.

Fig. 5.

Bioimaging of H2O2 using HPOX in hind limb I/R model in vivo. (a) In vivo imaging of H2O2 with HPOX/Rb after I/R in mouse hind limbs. Ischemia was induced for 1 h in both limbs and HPOX/Rb was directly injected just distal to the ligation sites (50 µg HPOX/Rb per site). Right hind limb was reperfused (red arrow) but left hind limb remained ligated (black arrow). Black arrow: ischemia, red arrow: reperfusion. Reperfusion at different time points as indicated. Rep = reperfusion. Acquisition time = 30 s/image. (b) In vivo imaging of H2O2 with HPOX/Rb in the presence or absence of catalase. Ischemia was induced for 1 h and 50 µg HPOX/Rb was directly injected into gastrocnemius muscles. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. Anti-apoptotic activity of HPOX nanoparticles

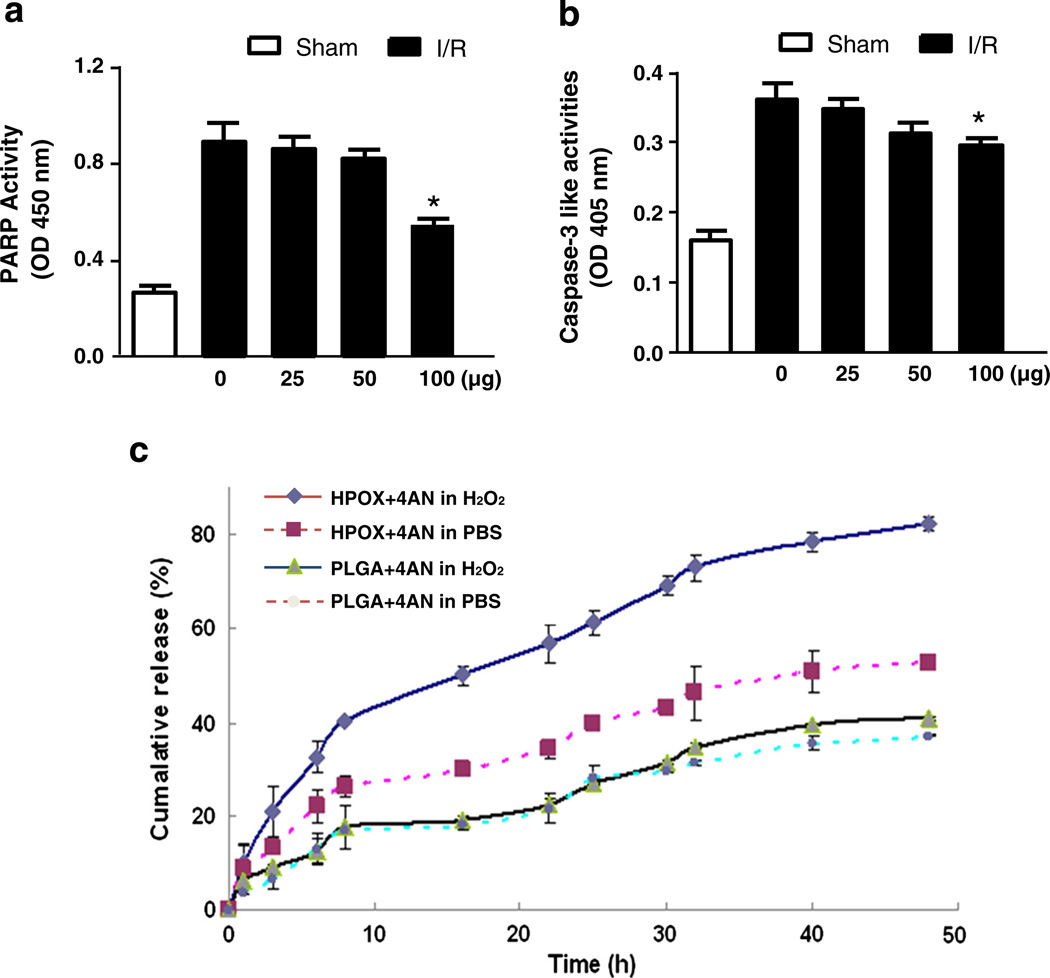

To test the potential of HPOX as therapeutics for the treatment of I/R injury, we first examined the ability of HPOX nanoparticles to inhibit the activation of polyADP ribose polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and caspase-3, both are critical enzymes involved in apoptosis [19–21]. HPOX was administered in the gastrocnemius muscle after hind limb I/R. Treatment with empty HPOX nanoparticles at a dose of up to 50 µg did not show significant inhibition of PARP-1 or caspase-3 activation by I/R (Fig. 6a & b). However, there was significant inhibition of PARP-1 and caspase-3 activities at the dose of 100 µg, suggesting that HPOX at a high dose exerts biologically significant anti-apoptotic activity presumed to be due to their potent antioxidant property.

Fig. 6.

Anti-apoptotic properties and pharmacokinetics of HPOX nanoparticles. (a–b) Quantification of PARP-1 and caspase-3 activities after I/R with different concentrations of HPOX nanoparticles. n = 4/group. *P < 0.05 vs no HPOX + I/R. (c) Release kinetics of 4-AN from HPOX/4AN compared with PLGA/4AN in the presence or absence of H2O2 (100 µM).

Then, we explored whether HPOX nanoparticles could be used as a targeted drug delivery system using 4-amino-1,8-napthalimide (4-AN) as a model drug. Previous studies demonstrated that 4-AN is a potent inhibitor of PARP-1, and treatment with the PARP-1 inhibitor has been shown to be effective in preventing apoptosis in heart in vitro and in vivo [22,23]. In this experiment, we formulated HPOX nanoparticles loaded with 4-AN (HPOX/4AN) to determine whether drug-loaded HPOX nanoparticles could rapidly and efficiently deliver the drug payloads in response to overproduction of H2O2 at the site of I/R injury. Initially, the in vitro release kinetics of 4-AN from HPOX/4ANwas studied in the presence or absence of H2O2 and the pharmacokinetic was compared with PLGA counterpart. The in vitro drug release profiles of HPOX/4AN demonstrated that HPOX showed faster cumulative release of 4-AN within 5 h, although for the first 3 h, PLGA and HPOX nanoparticles showed a similar rapid initial release pattern (Fig. 6c). The possible reason for initial release likely represents the release of 4-AN that was loosely adsorbed on the surface or poorly entrapped HPOX. H2O2 accelerated the drug release rate of HPOX. However, the drug release rate of PLGA was not affected by H2O2 and was slower than that of HPOX. In this study, the concentration of H2O2, 100 µM, was chosen after careful concentration of previous studies reporting H2O2-responsiveness. For examples, boronate-based fluorescent probes could detect intracellular H2O2 after the addition of exogenous 100 µM of H2O2 [24]. Mahmoud et al. developed inflammation responsive logic gate nanoparticles that degrade in the presence of 100 mM of H2O2[25].

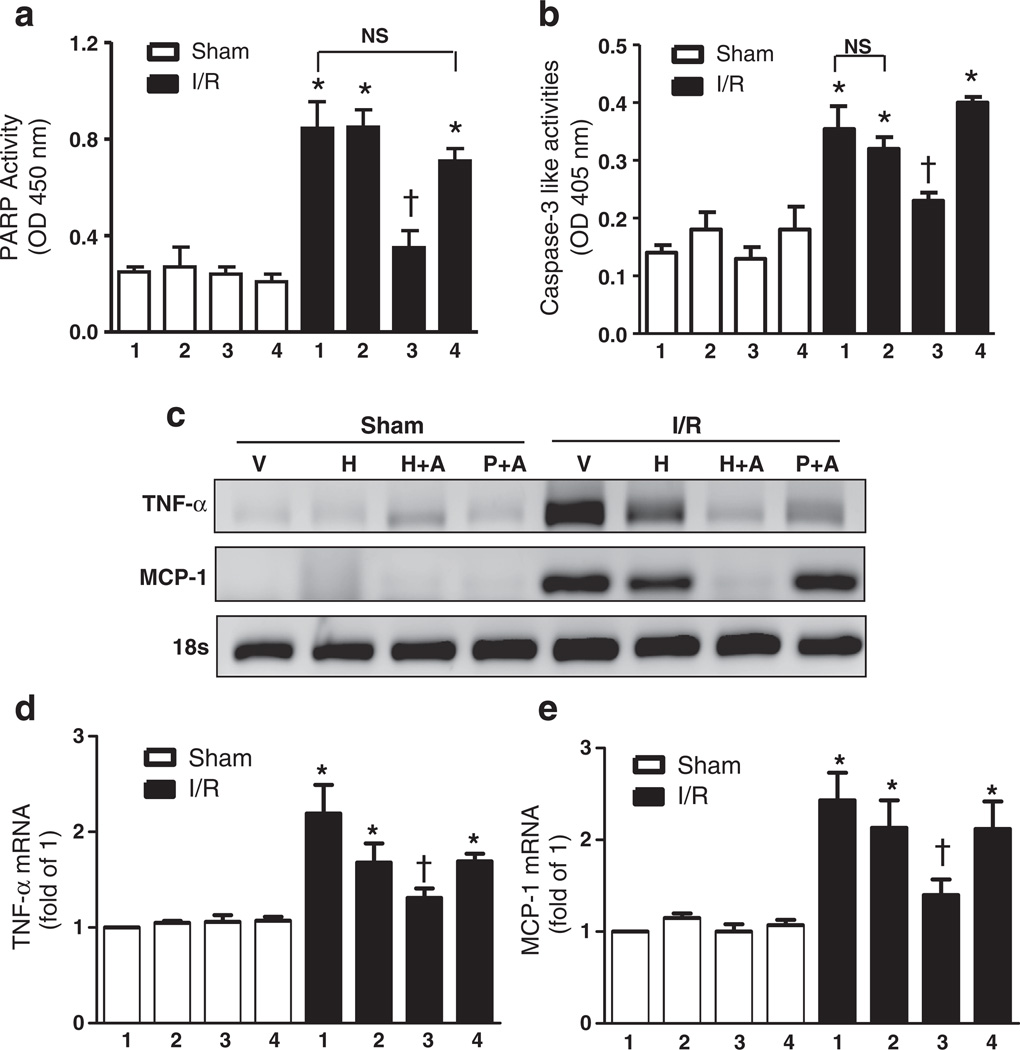

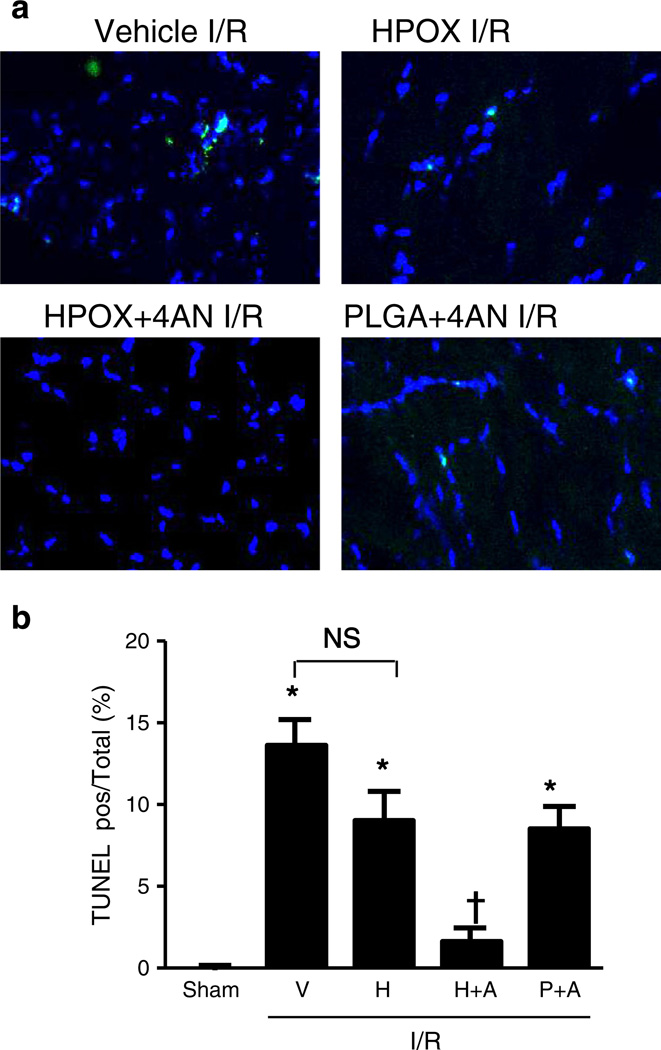

Next, we studied the efficacy of HPOX nanoparticles as I/R targeted drug delivery and potential synergistic therapeutic effects with a payload of 4-AN. HPOX/4AN (50 µg of nanoparticles/animal) was injected into the gastrocnemius muscle just distal to the reperfused occlusion. Vehicle, HPOX alone and PLGA/4AN served as control groups for HPOX/4AN. PARP-1 and caspase-3-like activities were significantly increased in vehicle group after I/R compared to the sham operated group (Fig. 7a & b). HPOX/4AN group significantly decreased the I/R− induced PARP-1 and caspase-3 activities compared to the I/R + vehicle group. HPOX alone showed modest but non-significant reduction of I/R induced caspase-3 activities. There was also significant attenuation of various markers of inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), after I/R in HPOX/4AN group compared to the I/R + vehicle group (Fig. 7c–e). HPOX alone showed modest but non-significant reduction of various pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, I/R-induced myocyte apoptosis was significantly inhibited in HPOX/4AN group compared to the I/R + vehicle group (Fig. 8a & b). Again, HPOX alone and PLGA/4AN showed modest but non-significant inhibition of myocyte apoptosis. Interestingly, PLGA nanoparticles had a higher drug loading capacity (~9.5%) than HPOX nanoparticles (~7.5%), but HPOX/4AN exhibited significantly higher therapeutic effects. The superior therapeutic effects of HPOX/4AN over PLGA/4AN can be explained by their faster drug release profile and intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of HPOX. Based on these findings, we conclude that HPOX nanoparticles have the potential to be used as an effective I/R-targeted drug delivery system, and intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of HPOX may further contribute to their overall beneficial effect during I/R injury.

Fig. 7.

I/R specific drug delivery of HPOX nanoparticles loaded with anti-apoptotic 4-AN as a model drug. (a–b) Quantification of PARP-1 and caspase-3 activities after I/R with or without 4-ANloaded HPOX. *P < 0.05 vs Sham of each group; †P < 0.05 vs IR group, n = 4/group. 1 = vehicle, 2 = HPOX, 3 = HPOX/4-AN, 4 = PLGA/4-AN. (c)mRNA levels of factors associated with inflammation. V = vehicle, H = HPOX, H+A = HPOX/4AN, P+A = PLGA/4AN. (d–e) Quantification of TNF-α (d) and MCP-1 (e) mRNA levels after I/R with or without 4-AN loaded HPOX. *P < 0.05 vs Sham of each group, n = 4/group. 1 = vehicle, 2 = HPOX, 3 = HPOX/4AN, 4 = PLGA/4AN.

Fig. 8.

Anti-apoptotic effect of HPOX nanoparticles loaded with PARP-1 inhibitor. (a) Representative TUNEL staining of myocytes, (b) quantification of TUNEL positive myocytes/total cells of gastrocnemius muscle after I/R with and without 4-AN loaded HPOX. *P < 0.05 vs Sham; †P < 0.05 vs IR+H, n = 4/group. V = vehicle, H = HPOX, H+A = HPOX/4AN, P+A = PLGA/4AN.

4. Discussion

Ideal drug delivery system would have combined target specificity with stimuli responsiveness to enhance the bioavailability of the drug [26]. It is therefore highly desirable to design stimuli responsive drug carriers for controlled drug delivery, which can release drugs on arrival at the target site [27]. Several such drug delivery systems have been generated that are responsive to pH, temperature, magnetic field, and concentrations of electrolytes or glucose [26,28]. However, these stimuli-responsive systems tend to be more generalized and may not be specific to the affected area. In this study, we engineered stimuli-responsive nanoparticles that are able to react with endogenously generated H2O2 with high sensitivity and specificity.

Tissue damage is the most important determinant of morbidity and mortality after various conditions that are associated with increased H2O2 production, such as myocardial infarction, vascular thromboembolic events, post cardiovascular surgery, and post traumatic injuries [2,4,29,30]. Therefore, limiting cellular death is paramount to favorable outcomes in these conditions. Particularly, suppression of ROS overproduction during these conditions using various antioxidants has been shown to effectively block the deleterious effects of ROS, such as apoptosis, in experimental settings in vitro and in vivo [1,31]. However, the beneficial effects of antioxidant therapy in human clinical studies have been disappointing [32,33]. One of the main reasons for the lack of benefit in the clinical setting may be due to the fact that non-specific suppression of ROS is not desirable. A similar issue also complicates anti-apoptosis therapy. Even though inhibition of apoptosis has been shown to be effective in preventing tissue damage in various I/R models, the use of anti-apoptotic drugs has been limited by potential side effects, such as pre-existing tumor proliferation [22,23,34–36]. In these cases, I/R-specific drug delivery systems will allow targeted release of drugs into specific areas or tissues that are undergoing a pathological process. The approach based on H2O2-responsive HPOX will allow high concentrations of drugs to be delivered to the affected area. In addition, non-toxic degradation products of HPOX with their favorable intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties offer additional benefits of being used for I/R injuries. Thus, this targeted strategy will not only be more effective but will significantly limit potential side effects of the drug. HPOX nanoparticles are, we believe, the first multifunctional nanoparticles that are able to image H2O2 in vivo, possess intrinsic antioxidant and antiinflammatory therapeutic properties, and are capable of delivering drugs rapidly and effectively for the treatment of I/R injury.

5. Conclusions

HPOX incorporating naturally occurring antioxidant HBA was formulated into solid nanoparticles which could encapsulate fluorescent dyes or drugs. HPOX nanoparticles showed intrinsic antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activities in cell culture and a mouse hind-limb I/R injury. HPOX nanoparticles with fluorophore were also able to detect endogenously overproduced H2O2 generated in I/R injury by performing chemiluminescence reactions. These experiments are the first steps in developing a potential bioimaging agent and a targeted drug delivery system that will minimize side effects while being able to deliver higher drug concentrations to localized areas that are specifically affected during I/R. We anticipate the enormous potential of multifunctional HPOX nanoparticles for the H2O2-associated diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the World Class University Program (R31-20029, DL and PMK) and Basic Science Research Program (2010-0021903, DL) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Korea, and National Institutes of Health RO1 HL091998 (PMK).

References

- 1.Gottlieb RA, Burleson KO, Kloner RA, Babior BM, Engler RL. Reperfusion injury induces apoptosis in rabbit cardiomyocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:1621–1628. doi: 10.1172/JCI117504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeroudi MO, Hartley CJ, Bolli R. Myocardial reperfusion injury: role of oxygen radicals and potential therapy with antioxidants. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994;73:2B–7B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zweier JL. Measurement of superoxide-derived free radicals in the reperfused heart. Evidence for a free radical mechanism of reperfusion injury. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:1353–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002;10:620–630. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilgun-Sherki Y, Rosenbaum Z, Melamed E, Offen D. Antioxidant therapy in acute central nervous system injury: current state. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:271–284. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aragno M, Cutrin JC, Mastrocola R, Perrelli MG, Restivo F, Poli G, et al. Oxidative stress and kidney dysfunction due to ischemia/reperfusion in rat: attenuation by dehydroepiandrosterone. Kidney Int. 2003;64:836–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seong K, Seo H, Ahn W, Yoo D, Cho S, Khang G, et al. Enhanced cytosolic drug delivery using fully biodegradable poly(amino oxalate) particles. J. Control. Release. 2011;152:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y, Kwon J, Khang G, Lee D. Reduction of inflammatory responses and enhancement of extracellular matrix formation by vanillin-incorporated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffolds. Tissue Eng. A. 2012;18:1967–1978. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prudencio A, Schmeltzer RC, Uhrich KE. Effect of the linker structure on salicylic acid-derived poly(anhydride-esters) Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society. 2004;228:231, (POLY). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wattamwar PP, Mo YQ, Wan R, Palli R, Zhang QW, Dziubla TD. Antioxidant activity of degradable polymer poly(trolox ester) to suppress oxidative stress injury in the cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010;20:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park H, Kim S, Song Y, Seung K, Hong D, Khang G, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of hydroxybenzyl alcohol releasing biodegradable polyoxalate nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:2103–2108. doi: 10.1021/bm100474w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S, Park H, Song Y, Hong D, Kim O, Jo E, et al. Reduction of oxidative stress by p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol-containing biodegradable polyoxalate nanoparticulate antioxidant. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3021–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HJ, Hwang IK, Won MH. Vanillin, 4-hydroxybenzyl aldehyde and 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol prevent hippocampal CA1 cell death following global ischemia. Brain Res. 2007;1181:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee D, Khaja S, Velasquez-Castano JC, Dasari M, Sun C, Petros J, et al. In vivo imaging of hydrogen peroxide with chemiluminescent nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:765–769. doi: 10.1038/nmat1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhury S, Bae S, Ke QG, Lee JY, Kim J, Kang PM. Mitochondria to nucleus translocation of AIF in mice lacking Hsp70 during ischemia/reperfusion. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2011;106:397–407. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S, Hwang O, Lee I, Lee G, Yoo D, Khang G, et al. Chemiluminescent and antioxidant micelles as theranostic agents for hydrogen peroxide associated-inflammatory diseases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22:4038–4043. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee I, Hwang O, Yoo D, Khang G, Lee D. Detection of hydrogen peroxide in vitro and in vivo using peroxalate chemiluminescent micelles. Bull. Kor. Chem. Soc. 2011;32:2187–2192. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Virag L, Szabo C. The therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:375–429. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, et al. Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science. 2002;297:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, Wolf BB, Casiano CA, Newmeyer DD, et al. Ordering the cytochrome c-initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2-3-6-7-8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner [In Process Citation] J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:281–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae S, Siu PM, Choudhury S, Ke Q, Choi JH, Koh YY, et al. Delayed activation of caspase-independent apoptosis during heart failure in transgenic mice overexpressing caspase inhibitor CrmA. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;299:H1374–H1381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00168.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhury S, Bae S, Kumar SR, Ke Q, Yalamarti B, Choi JH, et al. Role of AIF in cardiac apoptosis in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes from Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;85:28–37. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller EW, Albers AE, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. Boronate-based fluorescent probes for imaging cellular hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16652–16659. doi: 10.1021/ja054474f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmoud EA, Sankaranarayanan J, Morachis JM, Kim G, Almutairi A. Inflammation responsive logic gate nanoparticles for the delivery of proteins. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011;22:1416–1421. doi: 10.1021/bc200141h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng F, Zhong Z, Feijen J. Stimuli-responsive polymersomes for programmed drug delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:197–209. doi: 10.1021/bm801127d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onaca O, Enea R, Hughes DW, Meier W. Stimuli-responsive polymersomes as nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2009;9:129–139. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Yang SC, Kao CY, Pierce RH, Murthy N. Solid polymericmicroparticles enhance the delivery of siRNA to macrophages in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlag MG, Harris KA, Potter RF. Role of leukocyte accumulation and oxygen radicals in ischemia–reperfusion-induced injury in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H1716–H1721. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodruff TM, Arumugam TV, Shiels IA, Reid RC, Fairlie DP, Taylor SM. Protective effects of a potent C5a receptor antagonist on experimental acute limb ischemia–reperfusion in rats. J. Surg. Res. 2004;116:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang PM, Haunstetter A, Aoki H, Usheva A, Izumo S. Morphological and molecular characterization of adult cardiomyocyte apoptosis during hypoxia and reoxygenation. Circ. Res. 2000;87:118–125. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:1610–1618. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vivekananthan DP, Penn MS, Sapp SK, Hsu A, Topol EJ. Use of antioxidant vitamins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:2017–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black JH, Casey PJ, Albadawi H, Cambria RP, Watkins MT. Poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitor PJ34 abolishes systemic proinflammatory responses to thoracic aortic ischemia and reperfusion. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2006;203:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conrad MF, Albadawi H, Stone DH, Crawford RS, Entabi F, Watkins MT. Local administration of the Poly ADP-Ribose Polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, PJ34 during hindlimb ischemia modulates skeletal muscle reperfusion injury. J. Surg. Res. 2006;135:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hua HT, Albadawi H, Entabi F, Conrad M, Stoner MC, Meriam BT, et al. Polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibition modulates skeletal muscle injury following ischemia reperfusion. Arch. Surg. 2005;140:344–351. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.4.344. (discussion 51–2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]