Abstract

Objective

Endometrial biopsy (EMBx) and colonoscopy performed under the same sedation is termed combined screening and has been shown to be feasible and to provide a less painful and more satisfactory experience for women with Lynch syndrome (LS). However, clinical results of these screening efforts have not been reported. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the long-term clinical outcomes and patient compliance with serial screenings over the last 10.5 years.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the data for 55 women with LS who underwent combined screening every 1–2 years between 2002 and 2013. Colonoscopy and endometrial biopsy were performed by a gastroenterologist and a gynecologist, with the patient under conscious sedation.

Results

Out of 111 screening visits in these 55 patients, endometrial biopsies detected one simple hyperplasia, three complex hyperplasia, and one endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO Stage 1A). Seventy one colorectal polyps were removed in 29 patients, of which 29 were tubular adenomas. EMBx in our study detected endometrial cancer in 0.9% (1/111) of surveillance visits, and premalignant hyperplasia in 3.6% (4/111) of screening visits. No interval endometrial or colorectal cancers were detected.

Conclusions

Combined screening under sedation is feasible and less painful than EMBx alone. Our endometrial pathology detection rates were comparable to yearly screening studies. Our results indicate that screening of asymptomatic LS women with EMBx every 1–2 years, rather than annually, is effective in the early detection of (pre)cancerous lesions, leading to their prompt definitive management, and potential reduction in endometrial cancer.

Keywords: Combined screening, endometrial cancer screening, colonoscopy, Lynch syndrome, endometrial biopsy, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

Introduction

Lynch syndrome (LS), or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by a germ-line mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2) that increases the risk of cancer in these patients [1]. In a study of LS mutation positive patients in the United States, Stoffel [2] estimated lifetime risks for women of 43% for colorectal cancer (CRC) and 39% for endometrial cancer (EC). Similarly, Bonadona et al. [3] found a lifetime risk of 35% for endometrial cancer in French families with Lynch syndrome. Furthermore, women with LS have an estimated lifetime risk of 6.7–8% for ovarian cancer (OC) [1, 3, 4]. These cancers can occur at any age but typically occur at an earlier age of onset than the general population. Patients who develop an initial cancer are also at an elevated risk of developing second primary cancers [1, 4–6].

Due to these elevations in risk, screening recommendations have been implemented. In both women and men with LS, CRC screening with colonoscopy and performance of polypectomy has resulted in an 80% decreased incidence of CRC, and a reduction in both CRC-related and overall mortality [7–9]. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend colonoscopy starting at age 20–25 years or 2–5 years prior to the earliest colon cancer if it is diagnosed before age 25 and repeated every 1–2 years [8, 10–12]. This contrasts with the general population in which CRC screening is usually recommended starting at age 50, and repeated at intervals of up to10 years.

NCCN guidelines recommend prophylactic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) as an endometrial cancer risk reducing option for women with LS who have completed childbearing [12–14]. Prior to or when risk reducing surgery is not performed, screening guidelines based on consensus opinion include annual endometrial biopsy starting at age 30–35 or 5–10 years prior to the earliest diagnosis of EC in the family [11]. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) has also been used for endometrial cancer screening, but its efficacy is lacking. NCCN states there is no clear evidence to support screening for endometrial or ovarian cancer for women with LS, and annual office endometrial sampling, transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 measurement are described as optional [12]. Due to the elevated risk of endometrial cancer in these patients, and the lack of consensus with screening guidelines, many practitioners opt to screen these patients [11, 15]. EC is not routinely screened for in the general population because it typically presents with warning symptoms, including post-menopausal or otherwise abnormal uterine bleeding. The endometrial cancer in women with LS however, is more likely to begin before menopause, with an average age of onset of 48, when abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms are less obvious.

Although colonoscopy is typically performed under sedation, EMBx is usually performed in an office setting without anesthesia. Patients often experience moderate discomfort and cramps. Combined screening, with EMBx at the time of colonoscopy to take advantage of the intravenous sedation, has been shown to be feasible and acceptable to patients at our institution [16]. Following our proof of principal demonstration, combined screening is now being routinely performed. While we know that this combined screening approach is very well liked by our patients, we do not know how combining these two screening procedures will affect clinical outcomes and patient compliance.

The primary purpose of our study was to analyze pathologic outcomes of EMBx, with attention to diagnosis of hyperplasia and cancer, as well as resultant treatments following diagnosis. We also analyzed the pathologic profiles of colorectal polyps removed by colonoscopy and patient adherence with this combined screening program over a 10.5 year time period. Toward these ends, we performed a retrospective chart review of 55 women from our LS database who underwent EMBx and colonoscopy as a combined procedure.

Methods

Patient selection

LS patients were identified following referral for high-risk gynecologic management, and then scheduled for combined screening in coordination with their upcoming endoscopy. All routine EMBxs for LS patients are offered as joint procedures with colonoscopy. A total of 62 women had undergone combined screening from July 1, 2002, to March 1, 2013, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Women were identified if they had undergone one or more combined screening visits for elevated risk of EC. For the current study, patients were included only if they either met Amsterdam II criteria, or had a genetic mutation for LS. Seven patients were excluded based on these criteria, leaving 55 women who were included in our study. Of these, 32 (58%) patients had MMR mutations: MSH2 in 17 (53%) patients, MLH1 in 8 (25%) patients, MSH6 in 4 (13%), and PMS2 in 3 (9%). The remaining 23 (42%) patients met Amsterdam II criteria.

Data collected

For our analysis of all study-eligible patients, we collected and retrospectively evaluated data from the patients’ medical record for each patient’s age, height, weight, diagnostic criteria for LS, CA125 levels and pelvic ultrasonography (including endometrial stripe thickness), pathology results from EMBx and colonoscopy, intervals between combined screenings, gravidity, parity, race/ethnicity, menopausal status, all cancer diagnoses preceding and during the study period, cervical stenosis, and surgeries performed owing to combined screening results. This study received approval from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board.

Clinical examination

The annual clinic visit included a physical examination, Pap smear, pelvic examination, CA125 measurement, TVUS, and genetic counseling as needed starting at age 30. A review of clinical symptoms included whether the patient had experienced early satiety, abdominal bloating, pelvic pain or pressure, abnormal uterine bleeding, or postmenopausal bleeding. These patients had also been seen by the gastroenterologist prior to colonoscopy, and by a genetic counselor.

TVUS

TVUS was ordered for ovarian cancer screening on all patients starting at age 30 on a yearly basis. Interpretation by the radiologist included measurement of uterine size, uterine anatomy, endometrial stripe thickness, and ovarian morphology. If abnormal ovarian findings were reported, follow-up imaging was repeated after a shortened interval. Endometrial stripe thickness on TVUS was documented, but only used for retrospective analysis, as routine EMBx was performed during the study. Endometrial stripe thickness was deemed abnormal (during the retrospective analysis) when ≥ 12 mm in premenopausal women, or ≥ 5 mm in postmenopausal women [17, 18].

Combined screening/EMBx

At the time patients were originally seen, combined screening consisted of a colonoscopy performed by a gastroenterologist followed by an EMBx performed by a gynecologist, both while the patient was under intravenous sedation in the endoscopy suite. The endometrial biopsy portion of the combined screen was started at age 30. Negative results from a urine pregnancy test were required before EMBx could be carried out. As time progressed the order of the procedures were changed and the gynecologist went first followed by the gastroenterologist. This modification allowed the gynecologist to finish quickly and return to their clinic, and not have to wait for the colonoscopy to be completed.

Combined screenings were performed in the endoscopy suite under intravenous sedation using versed, fentanyl and on occasion propofol. The patient was placed on a stirrup-equipped stretcher. For the EMBx, the patient’s feet were moved into the stirrups and the patient placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. The EMBx was performed using a 3- or 4-mm pipelle (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT) with or without a tenaculum. A bimanual examination of the uterus and ovaries was performed upon completion of the EMBx. Gynecologic supplies for the EMB were brought to the endoscopy suite by the clinical nurse. If cervical stenosis or insufficient endometrial tissue was encountered, hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage were scheduled.

Colonoscopy

Upon completion of the EMBx, the patient was taken out of lithotomy and placed in the left lateral position for colonoscopy. Visualization was aided using indigo carmine dye and retroflexion in the right colon. Completion of colonoscopy was documented by visualization of the appendiceal orifice or cannulation of terminal ileum. Polyps were removed by cold biopsy or snare polypectomy, with or without cautery.

Pathology review

One pathologist reviewed the EMBx, hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) specimens. A variety of gastrointestinal pathologists reviewed the specimens taken at colonoscopy.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and the lengths of screening intervals. The Fisher’s exact test was used for calculating significance levels. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Adherence

We defined adherence as patients returning to MD Anderson for follow-up gynecologic surveillance examinations at intervals of <36 months.

Results

Demographics

The mean age at enrollment was 39.5 years (range 25.8 to 73.8). The majority were Caucasian (85%), with 7% Hispanic, 5% Asian, and 2% African American. Eighty-five percent were pre-menopausal, with 11% post-menopausal and 4% peri-menopausal. The majority, 78% were multiparous with 22% nulliparous. Weight distribution was 51% overweight or obese and 49% normal weight. Two women (3.6%) had cervical stenosis and underwent hysteroscopy with dilation and curettage. One patient with cervical stenosis had successful EMBx during CS the following year and underwent hysterectomy thereafter, and the other patient was lost to follow-up.

Serial screens per patient and screening intervals

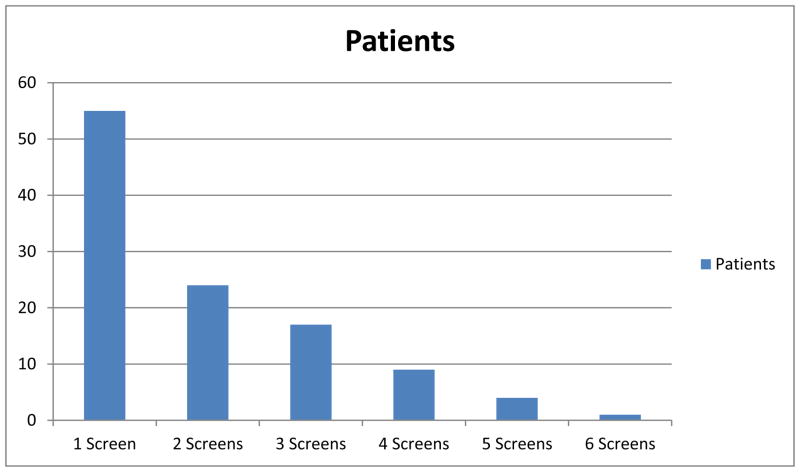

The combined screenings were scheduled according to the recommended colonoscopy schedule for patients with LS, at 1–2 years intervals. We recommended the EMBx portion of the CS starting at age 30 years. During the 10.5-year study period, a total of 111 CS surveillance visits were performed in 55 patients. All patients underwent at least one combined screening. Twelve women were enrolled in a one-time combined screening trial and had no plans of returning to our institution for further screenings. Of the remainder, 24 women had two consecutive combined screenings, 17 had three such screenings, nine had four screenings, four had five screenings, and one had six consecutive screenings, as shown in Figure 1. The overall median screening interval (defined as the time between one screening and the next) was 15.5 months (range, 1–71 months).

Figure 1.

Patients with consecutive serial combined screening visits

EMBx results, treatment of abnormalities, and outcomes

In 5 patients, endometrial biopsy yielded abnormal findings, as shown in Table 1. Pathology results showed one case of simple hyperplasia (SH) without atypia, two cases of complex hyperplasia (CH) without atypia, one case of complex atypical hyperplasia (CAH), and one case of endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EC), FIGO grade 1A. Four women were found to have abnormal endometrial pathology at their first screening, and one woman was found to have abnormal endometrial pathology at her second screening (6.7 months after the first). This second EMBx was performed along with an early repeat colonoscopy secondary to finding a colorectal polyp with tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia at the initial screen. No further high-grade dysplasia was found during repeat colonoscopy.

Table 1.

Positive EMBx Findings

| EMBx | Criteria | Treatment | Final Pathology | BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH | MLH1 | TAH/BSO | CAH | 33.6 |

| CH | ACII | OCPs | No Hyperplasia | 26.1 |

| CH | MLH1 | Levonorgestrel IUD | No Hyperplasia | 33.2 |

| CAH | MSH2 | TLH/BSO | CAH | 22.6 |

| EC FIGO grade 1A | MLH1 | TAH/BSO/staging | CAH | 32.5 |

Body Mass Index (BMI); Complex Hyperplasia (CH); Complex Atypical Hyperplasia (CAH); Simple Hyperplasia (SH); Amsterdam Criteria II (ACII); Oral Contraceptive Pills (OCPs); Endometrial Cancer (EC); Total Abdominal Hysterectomy (TAH)/Bilateral Salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO); Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy (TLH); Intrauterine Device (IUD)

Three of those five women (one with SH without atypia, one with CAH, and one with EC) proceeded to hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. All final pathology results showed CAH, including the patient with EC on biopsy. Both patients with CH without atypia chose conservative management. One of two patients with CH without atypia chose to take oral contraceptives, and EMBx performed 6 months after the initial screening showed no evidence of hyperplasia. The second woman with CH without atypia opted for a levonorgestrel intrauterine device, and had no evidence of hyperplasia on her next two screens (10.3 and 14.5 months later). Four out of five (80%) of the patients with abnormal endometrial pathology had germ-line mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes; three patients with a MLH1 mutation, and one with a MSH2 mutation. Out of 55 patients 1/23 (4.3%) of patients identified by Amsterdam II criteria and 4/32 (12.5%) of patients identified with mutations had abnormal endometrial pathology. No statistically significant difference was seen.

CA125 and TVUS results

All CA125 measurements were normal (<35 U/mL; data not shown), and no cases of OC were detected. Although six patients had abnormal ovarian findings on TVUS, all but one of these abnormalities resolved spontaneously, as visualized on follow-up TVUS. One patient had a change in management owing to an abnormal ultrasonography finding of a 6.1-cm ovarian cyst with septations and nodularity, with a normal CA125 measurement. She underwent laparoscopic removal of the cyst, with resultant benign pathology.

Fifty-four of the 55 women had at least one TVUS, with a mean endometrial thickness of 5.4 mm (range 1–16 mm). Results showed that 4/5 of the abnormal pathology findings had normal endometrial thickness measurements, including the patient with adenocarcinoma. These measurements were analyzed retrospectively.

Physical and gynecologic examination

No signs or symptoms of LS-associated cancers were detected on the yearly physical and gynecologic examinations.

Cancer diagnosis

Seventeen cancers were diagnosed in these 55 patients, 13 (76%) prior to our study period. They included 11 colon cancers, one breast cancer, and one thyroid cancer. Four (24%) cancers occurred during the screening period, one each of cancer of the endometrium (diagnosed on combined screening), breast, thyroid, and anaplastic astrocytoma.

Colonoscopy results, treatment of abnormalities, and outcomes

Polyps were removed in 29 (53%) patients during serial colonoscopies. In total, 70 polyps were removed, of which 29 (42%) polyps were neoplastic. Findings included 27 tubular adenomas, one tubular adenoma with high grade dysplasia, and one tubulovillous adenoma. Patients with precancerous polyps were scheduled to return for repeat colonoscopy in one year.

Adherence

Adherence, defined as patients returning for surveillance examinations within a three year interval, was 88%. We excluded those women who had only planned one screening visit. In general, the follow-up interval was determined by the gastroenterologist based on findings on colonoscopy. The median follow-up interval was 15.5 months, consistent with NCCN recommendations for colonoscopy at 1–2 year intervals.

Discussion

This is the first study reporting outcomes in women undergoing same-session combined colon and endometrial cancer screening. Surveillance of 55 asymptomatic women with LS, using a combined technique of colonoscopy and EMBx, under IV sedation, was well-tolerated and effective in the detection of early endometrial lesions and colonic polyps.

Initial EC screening studies in LS patients by Dove-Edwin and Rijcken evaluated endometrial thickness on TVUS; however, TVUS alone lacked sensitivity [17, 19]. Due to these findings, endometrial thickness on TVUS was not used in our study [17, 19, 20]. When our data on endometrial thickness was retrospectively analyzed, four out of five of the patients with abnormal endometrial sampling had normal endometrial thickness on TVUS. If endometrial thickness had been utilized in our study to determine the need for EMBx, four out of five of the abnormal endometrial specimens would have been missed.

It is well accepted that simple endometrial hyperplasia is not an immediate precursor to EC. However most investigators feel, and it has been previously shown, that simple hyperplasia does have at least a small risk (1%) of progressing to cancer in sporadic EC [21]. In LS patients, Nieminen et al. [22], showed MMR deficiency in 7% of normal endometrium, 40% of simple hyperplasia, 100% of complex hyperplasia without atypia, and 92% of complex hyperplasia with atypia. Together these studies suggest that in LS, SH and CH with or without atypia represents precursors of EC. Based on these data, EMBx in our study detected endometrial cancer in 0.9% (1/111) of surveillance visits, and premalignant hyperplasia in 3.6% (4/111) of screening visits. In total, pathologic endometrial findings were found in 4.5% (5/111) of surveillance visits. Our endometrial pathology detection rates using routine serial EMBx concur with those previously documented. Our study agrees with the majority of the current literature that EMBx appears to be superior to TVUS in the detection of (pre)cancerous endometrial lesions. Performing these procedures using a combined screening approach, aids in the comfort of the procedures.

Two other studies also showed that EMBx was more effective than TVUS for LS screening. In the first surveillance study, Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. [20] screened 175 LS patients every 2–3 years and found 14 cases of EC in total, with 11 cases found with screening. EMBx diagnosed eight of 11 patients with EC whereas TVUS detected only four EC cases. In addition, EMBx detected premalignant hyperplasia in 14 other cases. The number of cancers diagnosed by EMBx was 2.2% (11/503) of surveillance visits, and hyperplasia 2.8% (14/503) of surveillance visits [20, 23].

Gerritzen et al. [24] also showed that endometrial surveillance with routine annual endometrial sampling was more effective than TVUS alone for the diagnosis of endometrial (pre)malignancy. They performed 64 routine EMBx procedures and cancer was detected in 1.6% (1/64) of surveillance visits, and hyperplasia detected in 4.9% (3/64) of surveillance visits [23, 24].

Ultrasound was performed in our study for the evaluation of ovarian cancer, and not specifically for the evaluation of EC. In light of the EC detection rates using serial EMBx, we propose that endometrial biopsy alone, without the addition of TVUS could be feasible for future EC screening studies. Because TVUS has demonstrated low yield for the detection of ovarian malignancy [23], it is unclear the benefit of TVUS in screening guidelines.

In our study, the rationale for adding the endometrial biopsy to the colonoscopy under sedation came from the desire to diminish pain and discomfort for the patients. It also combined two procedures into one. EMBx in non-LS symptomatic patients is usually performed once or twice in a lifetime, and only in a limited number of women. In contrast, women with LS require serial endometrial biopsies, which given the discomfort and anxiety associated with the procedure, may lead to decreased compliance. In a previous study by Manchanda et al., annual outpatient hysteroscopy and endometrial sampling in 41 women for LS screening reported high patient acceptance and higher accuracy compared to TVUS. In our study, pairing the biopsy with the colonoscopy while under sedation has allowed our patients to feel comfortable with these frequent screening recommendations. Compliance with follow-up in our study was 88%, possibly owing to the increased comfort offered with the CS with sedation approach.

In our facility, combined screenings are scheduled at the beginning of the day, allowing gynecologists to return to their clinics with little interruption of their schedule. Early on in the feasibility study, the gastroenterologist typically went first. However, as time went on the gynecologist went first, in the interest of getting the quicker part of the procedure done, so the gynecologist could leave and not have to wait on the gastroenterologist to perform the colonoscopy. As shown in the feasibility study [16], the EMBx added a median time of 5 minutes (range, 1–12 minutes), whereas colonoscopy duration for the study endoscopist averages about 19 minutes. No increases in anesthetic medication dosing or change in type of sedation offered were necessitated by the addition of the EMBx.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer other than LS include: nulliparity, obesity, older age, tamoxifen use, and unopposed estrogen exposure. Of the five LS patients with abnormal endometrial pathology, four were obese or overweight (Table 1), and one was nulliparous. Their mean age was 43.8 years (range, 34.6–53.4 years), and none used tamoxifen or unopposed estrogen. It is unclear whether obesity is an additive risk factor for women with LS. However, counselling LS patients on known modifiable risk factors for endometrial cancer, especially obesity, is a reasonable clinical strategy.

Colonoscopy detected 29 precancerous polyps with no cases of CRC. No interval EC or CRC was detected, and no ovarian cancer was detected

The intervals between combined screenings were based on the recommended colonoscopy follow-up frequency of every 1–2 years [8, 9], rather than annual EMBx. Our median screening interval was 15.5 months, and our endometrial pathology detection rates were comparable to yearly screening studies. Based on our findings, we recommend changing to a 1–2 year screening interval, in parallel with the colonoscopy recommendations.

A study limitation was the retrospective nature of the study as well as the inclusion of Amsterdam II criteria and mutation carrier status, rather than mutation carrier status alone for patient inclusion.

Conclusion

This is the first study reporting outcomes in women undergoing same-session colon and endometrial cancer screening. Women with LS require serial annual endometrial biopsies which given the discomfort of the procedure, may lead to decreased compliance. Combined screening under sedation is feasible and less painful than EMBx alone. Since these results were obtained with serial EMBx without consideration of endometrial thickness on ultrasound, we propose that EMBx alone could be feasible for EC screening. Our endometrial pathology detection rates were comparable to yearly screening studies. Our results indicate that screening of asymptomatic LS women with EMBx every 1–2 years, rather than annually, is effective in the early detection of (pre)cancerous lesions, leading to their prompt definitive management, and potential reduction in endometrial cancer.

Acknowledgments

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA016672.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, de la Chapelle A, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:214–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<214::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoffel E, Mukherjee B, Raymond VM, Tayob N, Kastrinos F, Sparr J, et al. Calculation of risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer among patients with Lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1621–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonadona V, Bonaiti B, Olschwang S, Grandjouan S, Huiart L, Longy M, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305:2304–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson P, Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Bernstein I, Aarnio M, Jarvinen HJ, et al. The risk of extra-colonic, extra-endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:444–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koornstra JJ, Mourits MJ, Sijmons RH, Leliveld AM, Hollema H, Kleibeuker JH. Management of extracolonic tumours in patients with Lynch syndrome. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:400–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasen HF. What is hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) Anticancer Res. 1994;14:1613–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dove-Edwin I, Sasieni P, Adams J, Thomas HJ. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic surveillance in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer: 16 year, prospective, follow-up study. BMJ. 2005;331:1047. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38606.794560.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Sistonen P. Screening reduces colorectal cancer rate in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1405–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, Aktan-Collan K, Aaltonen LA, Peltomaki P, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:829–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vos tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Nagengast FM, Griffioen G, Menko FH, Taal BG, Kleibeuker JH, et al. Surveillance for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: a long-term study on 114 families. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1588–94. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindor NM, Petersen GM, Hadley DW, Kinney AY, Miesfeldt S, Lu KH, et al. Recommendations for the care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to Lynch syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1507–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.12.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen LM, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, et al. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burt RW, Cannon JA, David DS, Early DS, Ford JM, Giardiello FM, et al. Colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1538–75. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasen HF, Blanco I, Aktan-Collan K, Gopie JP, Alonso A, Aretz S, et al. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut. 2013;62:812–23. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang M, Sun C, Boyd-Rogers S, Burzawa J, Milbourne A, Keeler E, et al. Prospective study of combined colon and endometrial cancer screening in women with lynch syndrome: a patient-centered approach. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:43–7. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dove-Edwin I, Boks D, Goff S, Kenter GG, Carpenter R, Vasen HF, et al. The outcome of endometrial carcinoma surveillance by ultrasound scan in women at risk of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma and familial colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1708–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvinen HJ, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Aktan-Collan K, Peltomaki P, Aaltonen LA, Mecklin JP. Ten years after mutation testing for Lynch syndrome: cancer incidence and outcome in mutation-positive and mutation-negative family members. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4793–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rijcken FE, Mourits MJ, Kleibeuker JH, Hollema H, van der Zee AG. Gynecologic screening in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:74–80. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Butzow R, Leminen A, Lehtovirta P, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen HJ. Surveillance for endometrial cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:821–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403–12. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<403::aid-cncr2820560233>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieminen TT, Gylling A, Abdel-Rahman WM, Nuorva K, Aarnio M, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, et al. Molecular analysis of endometrial tumorigenesis: importance of complex hyperplasia regardless of atypia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5772–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auranen A, Joutsiniemi T. A systematic review of gynecological cancer surveillance in women belonging to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) families. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:437–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerritzen LH, Hoogerbrugge N, Oei AL, Nagengast FM, van Ham MA, Massuger LF, et al. Improvement of endometrial biopsy over transvaginal ultrasound alone for endometrial surveillance in women with Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:391–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9252-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]