Abstract

Background

The prognoses of young breast cancer patients are poor. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the different characteristics and prognoses among different subtypes of young breast cancer patients.

Methods

The study included 1360 patients <40 years-old (y) and 3110 patients 40-50y with operable breast cancer in Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University. The characteristics, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were compared.

Results

The median follow-up was 54.1 months. More grade III tumors and more lymph-vascular invasions (P < 0.01) were presented in <40y group when compared with 40-50y group. More patients <40y presented with Luminal B (25.3% vs. 17.5%, P < 0.01) and triple negative (16.7% vs. 13.4%, P < 0.05) breast cancer while fewer had Luminal A tumor (48.5% vs. 59.2%, P < 0.01). Younger patients with tumors of both Luminal A and Luminal B types were at increased risk for worse DFS (P = 0.03, HR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.05-2.72; P < 0.01, HR = 3.61, 95% CI = 2.50-5.22) when compared with the older patients. Patients <40y with Luminal B tumor had a two point five fold higher risk of death compared with older counterparts (P < 0.01, HR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.35-4.79), however, a worse overall survival rate was not observed in the younger women with Luminal A breast cancer (P > 0.05). In multivariate analysis, Luminal B subtype was also a strong predictor of disease relapse (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.19, P < 0.01) in younger patients with Luminal subtype tumors.

Conclusion

Characteristics of breast cancer suggested a more aggressive biology in Chinese patients with breast cancer diagnosed at young age. Luminal B subtype may have a negative effect on the prognosis of young patients in China which should be validated further.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Young age, Subtype, Characteristics, Survival

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in developed countries. According to the American Cancer Society, there will be over 200,000 new breast cancer patients in the USA in 2010, accounting for 28% of all malignant tumors in women [1]. It was estimated that only 11% of breast cancer patients are diagnosed between 35-44 years of age (y); and less than 5% are diagnosed under the age of 35 [2]. However, the figure reported is significantly higher in Asian, especially in Chinese population (10-20% in total) [3,4]. Breast cancer, although rare in young women, in known to have more aggressive biological characteristics and is associated with a more unfavorable prognosis compared with older women [4-6]. As previous reported, it is known that 5-year overall survival (OS) of young breast cancer patients was 80-90% and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) was 70-80%, which were significantly lower than their older counterparts [7].

However, not all young breast cancer patients suffered from poor prognosis. To date, few well-designed study have focused on young age breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Although there is still no clear definition of ‘young’ breast cancer patients (ranging from 30 y to 45 y), the relationship of young breast cancer patients and breast cancer subtype remain great interest for investigation. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the different characteristics and prognoses among different subtypes of breast cancer between young breast cancer patients aged 39 or younger and the patients aged 40-50.

Methods

Patients and follow-up

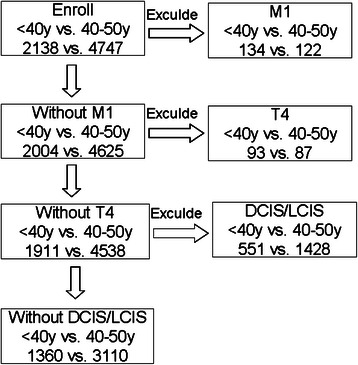

The medical records of 2138 and 4747 female patients aged <40y and 40-50y who had breast cancer diagnosed first time and were treated with breast surgery between Jan 1st, 2003 and December 31st, 2012, were retrospectively reviewed. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Cancer Hospital, Fudan University. The information was retrieved from the database of the Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. All patients were staged according to the 2007 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines [8,9]. Seven hundred and seventy-eight and 1637 patients were excluded from the two groups respectively according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Figure 1. Patients who required neoadjuvant therapy or who had metastastic disease were not included. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of these patients were classified by the inpatients’ computerised database, as required by the REMARK criteria [10,11]. All patients were required to have a complete physical examination, bilateral mammography, chest radioscopy, ECG, ultrasonography of breasts, axillary fossa, cervical parts, abdomen and pelvis, and routine blood and biochemical tests before surgery and adjuvant therapy when appropriate. Outpatient department records and records of personal contact with the patients, including routine correspondence and/or telephone calls, were used to follow the patients and determine the occurrence of loco-regional recurrence, distant metastasis or death. Patients returned to the Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University for follow-up every 3 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months in the third to fifth years, and annually after 5 years.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for study.

Standard treatment

All patients were required to have a comprehensive physical examination and a pre-operative evaluation before surgery. All of the mastectomies and lumpectomies were R0 resection (margin-clear resection). Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, post-mastectomy radiotherapy and/or endocrine therapy was determined by the risk of relapse and was based on the standard of care at the time of surgery. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was used to evaluate the status of estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR) in the tumors, as previously described. HER2 status was evaluated by IHC staining with (3+) being positive, (0 and 1+) being negative and (2+) requiring further evaluated by FISH. Four subtypes were defined: 1) Luminal A: ER(+) and/or PR(+), HER2(-), grade 1 or grade 2 tumors, 2) Luminal B: ER(+) and/or PR(+) and HER2(+) tumors or ER(+) and /or PR(+) and HER2(-) grade 3 tumors, 3) HER2+: ER(-), PR(-) and HER2(+) tumors, 4) Triple negative: ER-, PR-,HER2- tumors.

Endpoints and statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the first diagnosis of primary breast cancer to death from any cause. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from the diagnosis of breast cancer to the development of any local recurrence or metastatic disease. Patients without any evidence of relapse or death were censored at the last date they were known to be alive.

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The Chi-square test was used to compare patient and clinical-pathological characteristics between sub-groups, and the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis rank test was used for ordinal categorical variables. Survival distributions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and the comparison between subgroups was done by the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was carried out using Cox’s proportional hazard regression model, and hazard ratios (HR) are presented with their 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and discussion

Clinicopathologic characteristics

One thousand three hundred and sixty patients below the age of 40y and 3110 patients from 40y to 50y with primary breast cancer were included in the study. The patient characteristics of the two groups were summarized in Table 1. The median age was 35.2y and 46.0y respectively for the two comparison groups. Eighty patients (5.9%) younger than 40y had a family history in comparison with 1.4% in the group of 40-50y patients (P < 0.05). Two hundred and twenty-three (16.4%) patients aged 39 or younger received breast conservative surgery (BCS) while fewer older patients (7.6%) underwent BCS. A larger proportion of younger patients received chemotherapy (93.2% vs. 90.1%) and radiotherapy (25% vs. 17.4%). However, the difference were not statistically significant in all adjuvant therapies between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients according to age

| Age | <40y | 40 ~ 50y | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| character | No. | % | No. | % | |

| T stage | <0.01 | ||||

| T1 | 520 | 38.2 | 1072 | 34.5 | |

| T2 | 625 | 46.0 | 1914 | 56.3 | |

| T3 | 215 | 15.8 | 124 | 9.2 | |

| N stage | 0.07 | ||||

| N0 | 626 | 46.0 | 1580 | 50.8 | |

| N1 | 324 | 23.8 | 787 | 25.3 | |

| N2 | 324 | 23.8 | 606 | 19.5 | |

| N3 | 86 | 6.4 | 137 | 4.4 | |

| Family history | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 80 | 5.9 | 44 | 1.4 | |

| No | 1280 | 94.1 | 3066 | 98.6 | |

| Tumor Grade | <0.01 | ||||

| Grade I | 56 | 4.1 | 93 | 3.0 | |

| Grade II | 775 | 57 | 2233 | 71.8 | |

| Grade III | 529 | 38.9 | 784 | 25.2 | |

| Tumor type | 0.4 | ||||

| IDC | 1216 | 89.4 | 2762 | 88.8 | |

| ILC | 60 | 4.4 | 168 | 5.4 | |

| Others | 84 | 6.2 | 180 | 5.8 | |

| LVI | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 413 | 30.4 | 790 | 25.4 | |

| Negative | 947 | 69.6 | 2320 | 74.6 | |

| ER status | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 821 | 60.4 | 2133 | 68.6 | |

| Negative | 539 | 39.6 | 977 | 31.4 | |

| PR status | 0.9 | ||||

| Positive | 826 | 60.7 | 1894 | 60.9 | |

| Negative | 534 | 39.3 | 1216 | 39.1 | |

| HER2 status | 0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 390 | 28.7 | 647 | 20.8 | |

| Negative | 970 | 71.3 | 2463 | 79.2 | |

| Subtype | <0.01 | ||||

| Luminal A | 660 | 48.5 | 1959 | 59.2 | |

| Luminal B | 344 | 25.3 | 579 | 17.5 | |

| Her2 positive | 129 | 9.5 | 327 | 9.9 | |

| Triple negative | 227 | 16.7 | 445 | 13.4 | |

| Srugery | <0.01 | ||||

| BCS | 223 | 16.4 | 236 | 7.6 | |

| Mastectomy | 1137 | 83.6 | 2874 | 92.4 | |

| Endocrine therapy | 0.7 | ||||

| No | 204 | 15.0 | 442 | 14.2 | |

| Yes | 1156 | 85 | 2668 | 85.8 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.4 | ||||

| No | 92 | 6.8 | 308 | 9.9 | |

| Yes | 1268 | 93.2 | 2802 | 90.1 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.1 | ||||

| No | 1020 | 75.0 | 2568 | 82.6 | |

| Yes | 340 | 25.0 | 542 | 17.4 | |

Abbreviation:

IDC intraductal carcinoma.

ILC intralobular carcinoma.

LVI lymphovascular invasion.

ER eostregen receptor.

PR progesterone receptor.

BCS breast conservative surgery.

Younger patients tended to have a higher T stage (P < 0.01) and the trend of a higher N stage (P = 0.07) in comparison with the group of older patients. More grade III tumors (38.9% vs. 25.2%, P < 0.01) and more lymph-vascular invasions (30.4% vs. 25.4%, P < 0.01) were presented in the <40y group when compared with 40-50y group.

Breast cancer in women younger than 40 had a lower ER positive rate (60.4% vs. 68.6%, P < 0.01) but a higher HER2 positive rate (28.7% vs. 20.8%, P < 0.01) between the pair. The PR positive rate was similar between the two groups (P = 0.9). More patients <40y presented Luminal B (25.3% vs. 17.5%, P < 0.01) and triple negative (16.7% vs. 13.4%, P < 0.05) breast cancer while less of them presented Luminal A tumor (48.5% vs. 59.2%, P < 0.01, Table 1). The percentage of patients with HER2 positive, hormone receptor negative breast cancer was similar in both groups (9.0% vs. 9.9%, P > 0.05, Table 1).

When the cut-off age was set at 35y, almost the same characteristics as women aged 39 or younger were found with more of these patients having family history of breast cancer and BCS. Similarly, tumor of patients <35y presented higher T stage, N stage, higher grade and more lymph-vascular invasions. The proportion of Luminal B and triple negative breast cancer in <35y patients was also preponderant over that in 35-50y patients (Data not shown).

When we analyzed the subtypes according to molecular classification, more patients with HER2+ and Triple negative breast cancer presented higher T and N stage in comparison with those with Luminal groups (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in surgical modality or adjuvant therapy strategy among the four subtype groups (P > 0.05,data not shown).

Survival analysis

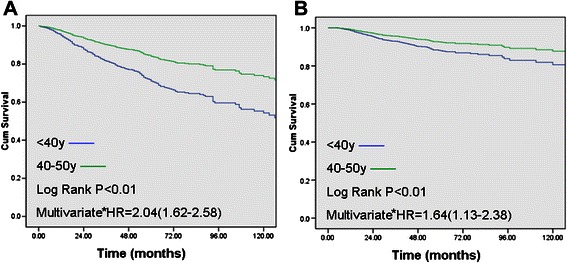

The median follow-up of the reported patients was 54.1 months (58.8 months for <40y group vs. 50.5 months for 40-51y group). The 5y DFS was 72% vs. 83% (P < 0.01) and the 5y OS was 87% vs. 93% (P < 0.01), in favour of patients in the 40-50y group (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Overall survival (A) and disease-free survival (B) of <40y group vs. 41-50y group. *Adjusted for tumor size (≤5 cm v >5 cm) and lymph node status. HR, hazard ratio.

There were significant differences between the two age groups with regards to the ascending of T stage and N stage subgroups (P < 0.01 both for OS and DFS, data not shown). The survival curves of the <40y group fell more sharply as the tumor grade increased when compared with women of older age group (P < 0.01 both for OS and DFS, data not shown). The effect of age on survival was significantly different between <40y group and 40-50y group, adjusted for tumor size and/or lymph node status (P < 0.01, HR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.13-2.38 for OS and P < 0.01, HR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.62-2.58 for DFS, Figure 2).

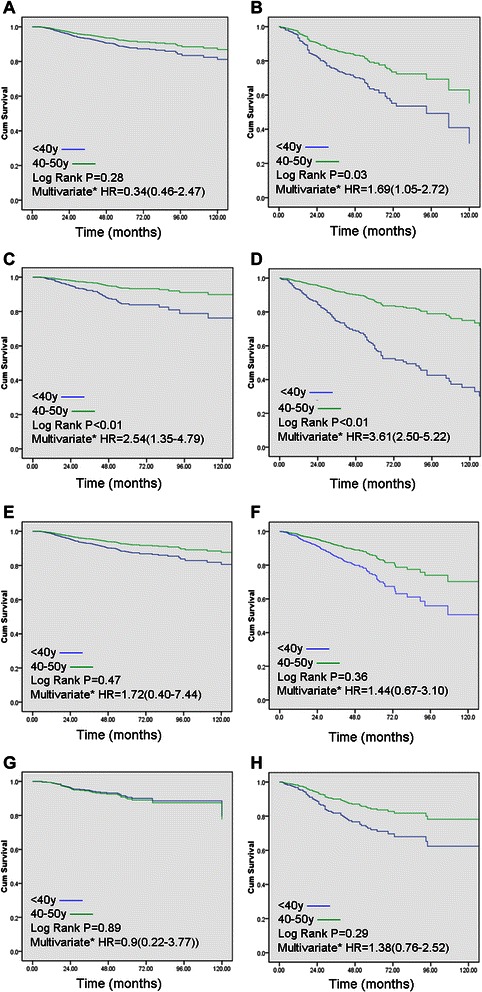

When compared different subtypes of breast cancer in the two different age groups (adjusted T and N stage in the analysis),younger patients with tumors classified as Luminal A and Luminal B type were at increased risk of poor DFS (P = 0.03, HR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.05-2.72; P < 0.01, HR = 3.61, 95% CI = 2.50-5.22). Additionally, patients <40y with Luminal B tumor had a two point five fold higher risk of death compared with older counterpart (HR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.35-4.79, Figure 3) while there was no significant risk of death associated with Luminal A subgroup (P > 0.05). In contrast, HER2+ and triple negative breast cancer showed no significant differences in DFS or OS between the younger and the older groups (P > 0.05, Figure 3). Furthermore, Luminal B subtype was a strong prognostic factor of disease relapse (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.19, P < 0.01) in younger patients with Luminal subtype tumor.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (A,C,E,G) and disease-free survival (B,D,F,H) between the two age groups, according to subtype (A/B: Luminal A, C/D: Luminal B, E/F: HER2, Triple negative: G/H). *Adjusted for tumor size (≤5 cm v >5 cm) and lymph node status. HR, hazard ratio.

Almost all the same trends were identified when comparing the <35y and ≥35y groups for subgroup comparisons as those found when comparing the two groups <40y and 40-50. Young age was shown being one of the major predictors for worse survival with respect to the larger tumour size group, the higher lymph node rate group and the Luminal B group.

Discussion

Breast cancer is a rrare in young women [12,13]. Consensus has been reached that breast cancer in young age is different from those of less young age [14]. Young patients often present with more aggressive biologic behavior, such as advanced stage, less ER positive expression, higher histological grade and more lymph-vascular invasion [15].

To our acknowledgement, this is the only study focused on breast cancer subtype and survival with largest sample of young patients. The most common surgery was mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection (83.6%) while breast conserving surgery was performed in only 16.4% patients. Studies have shown that young age alone is not a contraindication for breast conservation, but the risks should be discussed with the patient [16,17].

Our study has shown that young breast cancer patients are found at a more advanced stage and have more aggressive histologic and molecular characteristics, irrespective of the cut-off age at 35y or 40y. Younger patients frequently suffered from a higher T stage, a higher N stage andmore de-differentiation, which are all indicative of a poorer prognosis . In addition, this study is also consistent with the results of the Colleoni et al [12] that more vessel invasions and HER2 overexpresed tumors were more frequently found in breast cancer occurred in patients of young age. It was reported that approximately one-quarter of all breast cancer cases are hormone receptor negative, but a large proportion of hormone receptor negative tumor occurs in younger women [18]. Our study showed that younger patients had fewer hormone receptor-positive cancer (60%) in comparison with older women group aged between 40-50 (68%). These data are consistent with previous studies from other countries reporting less hormone receptor positivity in younger breast cancer patients [19].

Although environmental, lifestyle and genetic factors may have a great impact on the survival of young breast cancer patients, the TNM stage and biological features determine the prognosis. In our study, we found at a more advanced stage and have more aggressive histologic and molecular characteristics, irrespective of the cut-off age at 35y or 40y. Even in multivariate analysis, young age was a key point to both DFS and OS.

In this study, we found that Luminal A, Luminal B were the most common subtype in Chinese young breast cancer patients, followed by triple negative and HER2 positive with negative hormone receptor subtypes. Others reported that the Luminal B and triple negative were the most common subtypes in young patients because of the different definition of breast cancer subtype which associated with a increased risk of death in young patients [20]. In our study, young patients with Luminal B breast cancer had a 2.5 fold higher risk of death and 3.6 fold higher risk of relapse disease compared with the older counterpart Luminal A, HER2+ or triple negative, had similar survival outcomes in the two age groups. These findings were supported by recent studies reported by Chang’s group [21]. This finding has the accordance with the report of Lin et al [22]. Our study and others suggest that HER2 over-expression, high tumor grade and hormone receptor status may all be important prognostic factors in young breast cancer patients. Hormone receptor positivity may be important in managing young breast cancer patients because of the long exposure to the high level of estrogen [23]. Therefore, patients of young age with Luminal B tumor defined by positivity of both hormone receptors and HER2 expression will benefit from the combination of anti–HER2 target therapy, endocrine therapy and chemotherapy.

Our study also has some limitations in clearly defining young women breast cancer. Some of our cases had very limited follow-up which were censored too early, which might influence the survival analysis. Additionally, it is known that young breast cancer has a disproportionately high presentation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations [24,25]. However, genetic testing has not been well established in China. Further genetic and genomic investigations may accelerate our understanding of breast cancer in young patients. Lastly, the definitions of subtypes of breast cancer varied in the literature which could mislead the analysis and therefore conclusions. More reliable classification is needed to better address the tumor biology in young women’s breast cancer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, tumors in young women are more likely to present advanced disease with high grade and lymphovascular invasion. Young breast cancer patients in China are more likely to have Luminal B and triple negative tumor. Young patients with Luminal B tumor, but not other subtype, had the highest risk for relapse and death events over the older patients. Further research is required to investigate new treatment strategies in young patients with breast cancer, especially Luminal B subtype.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their willingness to cooperate with our study.

Abbreviations

- Y

Years-old

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- CI

Confidence intervals

- IDC

Intraductal carcinoma

- ILC

Intralobular carcinoma

- LVI

Lymphovascular invasion

- ER

Eostregen receptor

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- BCS

Breast conservative surgery

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LCT participated in the data collection, carried out the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. ZMX and GHD conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. HC helped to revise the grammar and design of the manuscript. XJ, HYY and MH participated in the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Li-Chen Tang, Email: forever_drawer@163.com.

Xi Jin, Email: 369128696@qq.com.

Hai-Yuan Yang, Email: 12211230025@fudan.edu.cn.

Min He, Email: minsmiler@126.com.

Helena Chang, Email: Hchang@mednet.ucla.edu.

Zhi-Ming Shao, Email: dgh20031126@gmail.com.

Gen-Hong Di, Email: zhimingshao@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence- SEER 17 Regs Public Use, Nov. 2008 Sub (2000-2006)-Linked to County Attributes-Total US, 1969-2006 Counties. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; 2009. Released April 2009 based on the November 2008 submission. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 3.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, St Louis J, Finkelstein DM, Yu KD, et al. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):e279–89. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han W, Kim SW, Park IA, Kang D, Kim SW, Youn YK, et al. Young age: an independent risk factor for disease-free survival in women with operable breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubsky PC, Gnant MF, Taucher S, Roka S, Kandioler D, Pichler-Gebhard B, et al. Young age as an independent adverse prognostic factor in premenopausal patients with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2002;3(1):65–72. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2002.n.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggard MA, O'Connell JB, Lane KE, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Ko CY. Do young breast cancer patients have worse outcomes? J Surg Res. 2003;113(1):109–13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4804(03)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang LC, Yin WJ, Di GH, Shen ZZ, Shao ZM. Unfavourable clinicopathologic features and low response rate to systemic adjuvant therapy: results with regard to poor survival in young Chinese breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singletary SE, Connolly JL. Breast cancer staging: working with the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(1):37–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly JL. Changes and problematic areas in interpretation of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th Edition, for breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(3):287–91. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-287-CAPAII. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(2):229–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes DF, Ethier S, Lippman ME. New guidelines for reporting of tumor marker studies in breast cancer research and treatment: REMARK. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(2):237–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colleoni M, Rotmensz N, Robertson C, Orlando L, Viale G, Renne G, et al. Very young women (<35 years) with operable breast cancer: features of disease at presentation. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2002;13(2):273–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon EK, Park HJ, Oh CM, Jung KW, Shin HY, Park BK, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among adolescents and young adults in Korea. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, Thurlimann B, et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2013;24(9):2206–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gajdos C, Tartter PI, Bleiweiss IJ, Bodian C, Brower ST. Stage 0 to stage III breast cancer in young women. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(5):523–9. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(00)00257-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles RC, Gullerud RE, Lohse CM, Jakub JW, Degnim AC, Boughey JC. Local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery: multivariable analysis of risk factors and the impact of young age. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1153–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litiere S, Werutsky G, Fentiman IS, Rutgers E, Christiaens MR, Van Limbergen E, et al. Breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy for stage I-II breast cancer: 20 year follow-up of the EORTC 10801 phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):412–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei XQ, Li X, Xin XJ, Tong ZS, Zhang S. Clinical features and survival analysis of very young (age < 35) breast cancer patients. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2013;14(10):5949–52. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.10.5949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molino A, Giovannini M, Auriemma A, Fiorio E, Mercanti A, Mandara M, et al. Pathological, biological and clinical characteristics, and surgical management, of elderly women with breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59(3):226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J, Wu CC, Xie ZM, Luo RZ, Yang MT. Comparison of Clinical Features and Treatment Outcome of Breast Cancers in Young and Elderly Chinese Patients. Breast care. 2011;6(6):435–40. doi: 10.1159/000332593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R. Prati YF, D.U. Chang, M.K. Lee, S. Apple, S.A. Huryitz, H. Chang: Effect of young age on aggressive subtypes of breast cancer (BC). SSO, Abstract#2092063, March 25-28, 2015. 2015.

- 22.Lin CH, Chuang PY, Chiang CJ, Lu YS, Cheng AL, Kuo WH, et al. Distinct clinicopathological features and prognosis of emerging young-female breast cancer in an East Asian country: a nationwide cancer registry-based study. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):583–91. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horn J, Opdahl S, Engstrom MJ, Romundstad PR, Tretli S, Haugen OA, et al. Reproductive history and the risk of molecular breast cancer subtypes in a prospective study of Norwegian women. Cancer causes control: CCC. 2014;25(7):881–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayraktar S, Amendola L, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Hashmi SS, Amos C, Gambello M, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of breast cancer in BRCA-carriers and non-carriers in women 35 years of age or less. Breast. 2014;23(6):770–4. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robson M, Gilewski T, Haas B, Levin D, Borgen P, Rajan P, et al. BRCA-associated breast cancer in young women. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1642–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]