Abstract

Purpose

To provide an improved platform for simple, reliable, and cost-effective genotyping.

Background

Modern fertility treatments are becoming increasingly individualized in an attempt to optimise the follicular response and reproductive outcome, following controlled ovarian stimulation. As the field of pharmacogenetics evolve, genetic biomarkers such as polymorphisms of the follicle stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) may be included as a predictive tool for individualized fertility treatment. However, the currently available genotyping methods are expensive, time-consuming or have a limited analytical sensitivity. Here, we present a novel version of “competitive amplification of differentially melting amplicons” (CADMA), providing an improved platform for simple, reliable, and cost-effective genotyping.

Methods

Two CADMA based assays were designed for the two common polymorphisms of the FSHR gene: rs6165 (c.919A > G, p. Thr307Ala, FSHR 307) and rs6166 (c.2039A > G, p. Asn680Ser, FSHR 680). To evaluate the reliability of the new CADMA-based assays, the genotyping results were compared with two conventional PCR based genotyping methods; allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) and Sanger sequencing.

Results

The genotype frequencies for both polymorphisms were 35 % (TT), 42 % (CT), and 23 % (CC), respectively. A 100 % accordance was observed between the CADMA-based genotyping results and sequencing results, whereas 5 discrepancies were observed between the AS-PCR results and the CADMA-based genotyping results. Comparing the CADMA-based assays to (AS-PCR) and Sanger sequencing, the CADMA based assays showed an improved analytical sensitivity and a wider applicability.

Conclusions

The new assays provide a reliable, fast and user-friendly genotyping method facilitating a wider implication in clinical practise.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-014-0329-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CADMA, Fertility treatment, FSHR polymorphisms, Genotype analysis, Pharmacogenetics

Introduction

Modern fertility treatments are becoming increasingly individualized in an attempt to optimise follicular stimulation and reproductive outcome following controlled ovarian stimulation (COS). Traditionally, measurement of factors like basal levels of Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), in combination with ultrasound guided measurement of the antral follicles, has been used to determine the starting dose of exogenous gonadotropin administered during COS [1].

Recently, a number of studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms of the gonadotropins and their receptors may affect the outcome of COS [2-6]. Especially the common polymorphisms of the FSH receptor (FSHR), rs6165 (c.919A > G, p. Thr307Ala, FSHR 307) and rs6166 (c.2039A > G, p. Asn680Ser, FSHR 680), has been shown to influence the sensitivity to exogenous FSH administration and the number of follicles recruited [2-6]. Despite some discordance in the literature [4, 7, 8], heterozygous and homozygous carriers of the Ser680 allele appear to require significantly higher amounts of FSH during COS in order to achieve successful stimulation, compared to the homozygous wild-type (Asn680) [4, 6, 9-14]. Although the FSHR polymorphisms have been shown to affect the outcome of COS, the direct clinical benefit in terms of increased pregnancy rates appear limited. Further, widespread use of genetic testing for FSHR polymorphisms also require implementation of relative expensive and time consuming methods, combined with an expertise that many fertility clinics do not have available.

The aim of this study was to provide a new, simple, reliable and cost-effective alternative method of genotyping the two common FSHR polymorphisms. The method is based on a modified version of “competitive amplification of differentially melting amplicons” (CADMA), which apply a three-primer system and high resolution melting (HRM) for genotyping. By modifying the primer design of CADMA, the method was optimized for simple and reliable genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms, such as the two common FSHR polymorphisms.

Materials and methods

Sample material

Seventy-eight Danish patients were included in this study. It is estimated that more than 90% is of Caucasian origin.

All sample material was obtained from surplus ovarian tissue from women undergoing fertility preservation by having ovarian tissue cryopreserved at Laboratory of Reproductive Biology, Rigshospitalet, Denmark. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg (H-2-2011-044) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

DNA extraction

Fifty patients were genotyped using DNA extracted from approximately 25 mg ovarian tissue, using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA samples were subsequently stored at −20 °C.

As ovarian tissue samples were not available for the remaining 28 patients, these patients were genotyped from DNA extracted from the granulosa cells (GC) of small antral follicles. The granulosa cells were obtained from aspirates of small antral follicles from individual follicles in connection with preparation of the tissue for freezing. The GC were isolated from the follicular fluid after a brief centrifugation (400 × g, 10 min), and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at−80 °C. DNA was extracted from the GC using Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), with slight modifications to the protocol (see supplementary material).

Modified CADMA primer design

The two novel genotyping assays (FSHR 307 and FSHR 680) are based on the principle of CADMA. The method was originally invented, to investigate cell-specific mutations in a large wild-type background [15, 16]. By applying a three-primer system, CADMA allows for simultaneous amplification of both mutated and wild-type sequences, detectable through high-resolution melting (HRM) [15].

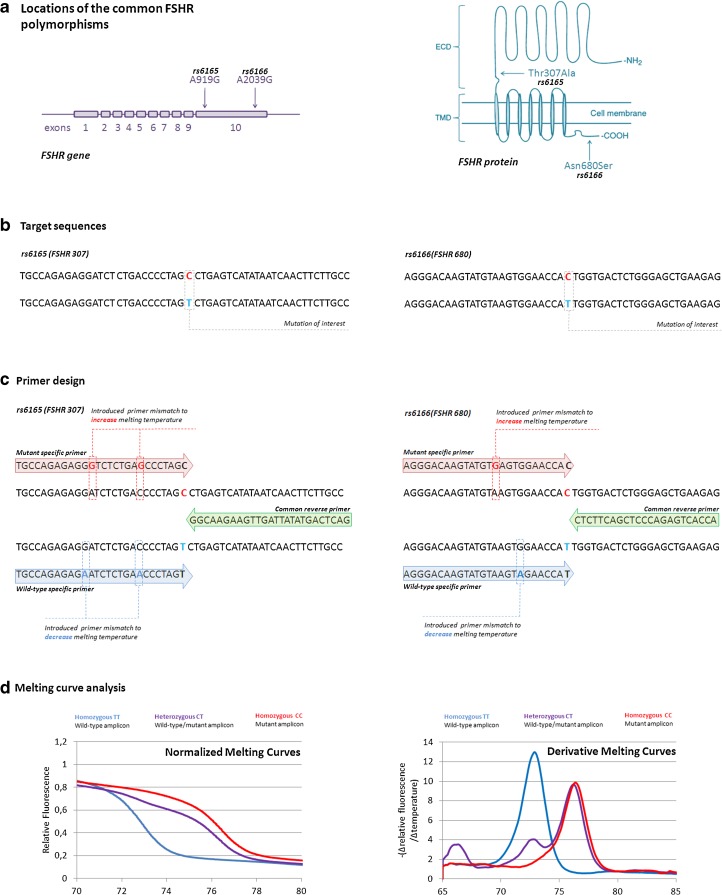

We have modified the three-primer system of CADMA for optimized genotyping of the common FSHR polymorphisms (Fig. 1). The first primer is designed to amplify only mutated sequences, including the SNP in the 3’ end. Furthermore, mismatches are included in the primer sequence, which introduces temperature increasing mutations into the “mutant” amplicon. Whereas the CADMA method utilizes a second primer that amplifies both wild-type and mutated alleles, we have designed the second primer to amplify only the wild-type sequences by including the SNP in the 3’ end. As for the mutant primer, mismatches are included in the wild-type primers, in order to introduce melting temperature decreasing mutations in the “wild-type” amplicon (Fig. 1c). The third primer, is a common reverse primer that anneals to both wild-type and mutant sequences. Following PCR, HRM analysis of the amplicons is performed, by which the melting curves of the amplicons are visualized (Fig. 1d). Because of the introduced mutations the amplicons differ in nucleotide content according to genotype, which can be visualized as genotype specific melting profiles (Fig. 1d). The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Modified primer design. a The gene and protein locations of the two commons polymorphisms rs6165 and 6166. Although both polymorphisms are present in the same exon, they reside in different protein domains of the receptor. Rs6165 are found in the extracellular domain (ECD) of the receptor, whereas rs6166 resides in the intracellular C-terminal of the receptor. b Mutated and wild-type sequences are amplified simultaneously using a three-primer system, based on the target sequence. c The first primer is designed to amplify only mutated sequences, with one or more melting temperature increasing mutations introduced in the mutated amplicon. The second primer is designed to amplify only wild-type, with one or more melting temperature decreasing mutations introduced in the wild-type amplicon. A third common primer is designed as a reverse primer. d The resulting amplicons differ in nucleotide content according to genotype, which will be reflected in melting temperatures, detectable through melting analysis d. The early peak (67 °C) observed in the negative derivative melting curves for the heterozygous (purple) samples, is due to the formation of heteroduplexes formed between wild-type and mutant amplicons. Figure modified from Casarini et al., 2011 and Kristensen et al., 2012 [15, 26].

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| SNP | Assay | Primer sequence (3’➙5’) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs6165 Thr307Ala | CADMA-based HRM assays |

Wild-type primer*: | CAGAGAGAATCTCTGAACCCTAGT |

| Mutation primer*: | CAGAGAGGGTCTCTGAGCCCTAGC | ||

| Common reverse primer: | GGCAAGAAGTTGATTATATGACTCAG | ||

| rs6166 Asn680Ser | CADMA-based HRM assays |

Wild-type primer*: | AGGGACAAGTATGTAAGTAGAACCAT |

| Mutation primer*: | AGGGACAAGTATGTGAGTGGAACCAC | ||

| Common reverse primer: | CTCTTCAGCTCCCAGAGTCACCA | ||

| rs6165 Thr307Ala | AS-PCR assays |

Wild-type primer: | GAGGATCTCTGACCCCTAGT |

| Mutation primer: | AGGATCTCTGACCCCTAGC | ||

| Control primer: | TAGCCTCAAGGGCAGGTATG | ||

| Common reverse primer: | GATGCAATGAGCAGCAGGTA | ||

| rs6166 Asn680Ser | AS-PCR assays |

Wild-type primer: | GACAAGTATGTAAGTGGAACCAT |

| Mutation primer: | GACAAGTATGTAAGTGGAACCAC | ||

| Control primer: | TTCACCCCATCAACTCCTGT | ||

| Common reverse primer: | TCCTGGCTCTGCCTCTTACA | ||

*Temperature-shifting mismatches in the primer sequences are highlighted in bold and underscored

PCR and HRM conditions

PCR and HRM analysis was performed on the LightCycler®480 Instrument II (Roche Diagnostics, Ropkreuz, Switzerland). The PCR was performed in a final volume of 10 μl, applying the LightCycler® 480 High Resolution Melting Master (Roche) as PCR/dye master mix. The final reaction mix for the FSHR 307 assay consisted of 2 μl template DNA (10 ng/μl), 5 μl LightCycler® 480 High Resolution Melting Master, 1.2 μl MgCl2 (25 μM), 0.3 μl FSHR 307 wild-type primer (10 μM), 0.1 μl FSHR 307 mutation primer (10 μM), 0.2 μl FSHR 307 common reverse primer (10 μM), and finally adding 1.2 μl ddH2O to a final volume of 10 μl.

A similar reaction mix was optimized for the FSHR 680 assay, with the following primer-concentrations: 0.1 μl FSHR 680 wild-type primer (10 μM) 0.3 μl FSHR 680 mutation primer (10 μM) and 0.2 μl FSHR 680 common reverse primer (10 μM).

The assays were optimized to perform at the same PCR cycling conditions. The protocol was initiated by one cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 61 °C for 15 s, 70 °C for 10 s, and finally, one cycle at 95 °C for 1 min. HRM was performed from 65 to 95 °C with a temperature increase of 0.1 °C/s with 50 acquisitions/°C. Each sample was run in duplicates.

For data analysis, the LightCycler® 480 series software version 1.5.0.39 was applied. The melting profiles were visualized using the software function “Melt Curve Genotyping”.

Allele specific PCR

In total, 42 samples were analysed with conventional AS-PCR followed by gel-electrophoresis, in cooperation with Molecular Genetic Reproductive Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden. PCR conditions have previously been described [17], and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Sanger sequencing

In total, 24 samples was analysed with Sanger sequencing, performed on the ABI Genetic Analyzer 3130 XL (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) using the control- and common reverse primers from the AS-PCR setup [17]. The PCR products were sequenced using a BigDye terminator kit v1.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufactures’ protocol with slight modifications, in which the single-stranded PCR was performed using 1 μl of the BigDye terminator in a final volume of 10 μl.

Results

Optimization of the CADMA-based genotyping assays

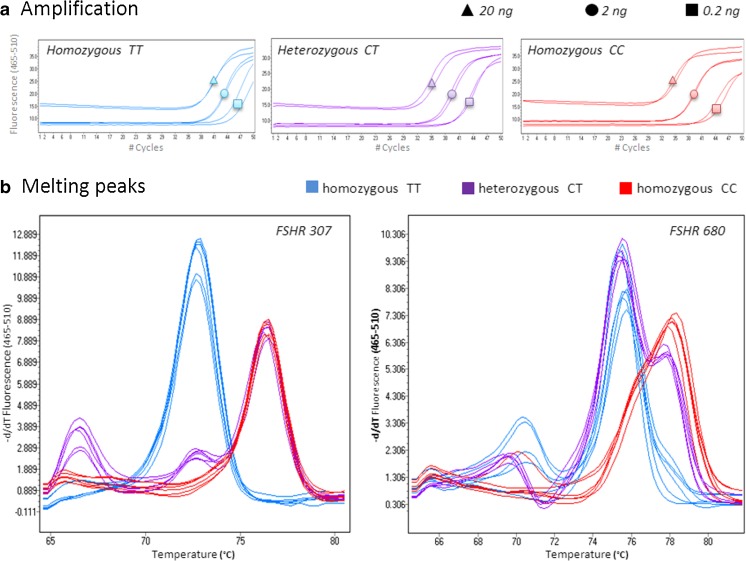

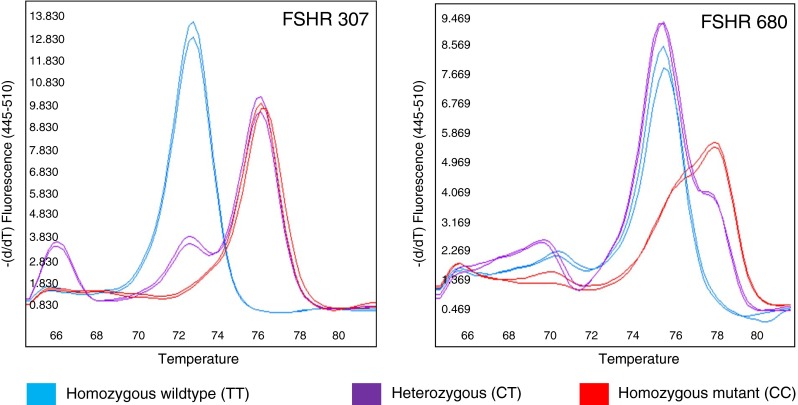

The assays were optimized using DNA of known genotype by adjusting relative primer concentrations and annealing temperature to allow maximum separation of the various genotypes by HRM. For each of the assays three distinct melting profiles, one for each of the three different genotypes, could readily be distinguished (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CADMA-based assays for FSHR genotyping. The negative derivative melting profiles of the two FSHR assays are shown. Based on the primer design, the amplicons have genotype-specific nucleotide content, resulting in three distinct melting curve profiles: (blue) homozygous wild-type (TT), (purple) heterozygous (CT), (red) homozygous mutant (CC)

Analytical sensitivity of the CADMA-based genotyping assays

The analytical sensitivity of the assays was tested by genotyping DNA inputs of 20, 2 and 0.2 ng from samples of all three genotypes (TT, CT and CC) for both polymorphisms.

The assays were able to reliably genotype DNA inputs down to 0.2 ng (Fig. 3). As expected, the samples of the three different DNA concentrations reached the exponential amplification at different cycle numbers, inversely proportional to DNA concentrations (Fig. 3a). The HRM analysis of the PCR products revealed that the melting profiles of samples of low DNA concentrations matched the reference profiles (Fig. 3b). A closer investigation of the melting peaks revealed a heteroduplex formation (small peak at 70 °C) in one homozygous CC sample (20 ng) in the FSHR 680 assay (Fig. 3b). This, however, did not influence the ability of the assay to reliably genotype the sample. Additionally, minor shifting in the late part of the homozygous TT curves (small shift at 78 °C) was observed in the FSHR 680 assay, in the samples of 2 and 0.2 ng (Fig. 3b). This could indicate some amplification had occurred from the mutant specific primer (CC), resulting in a small portion of the PCR product having incorporated a cytosine base (C) instead of a thymidine (T). However, with the vast majority of the PCR product being homozygous TT, the small shift does not influence the ability of the assay to reliably genotype samples of low input DNA.

Fig. 3.

Genotyping low input DNA. In order to investigate the analytical sensitivity of the FSHR assays, we tested the assays ability to genotype DNA samples of low input. As expected, the number of cycles needed to reach the exponential amplification was inverse proportional to the DNA concentrations a. Visualized melting peaks b revealed that the melting curve profiles of samples of low DNA concentrations matched the genotype specific melting curve profiles.

Comparison between the CADMA-based genotyping assays, AS-PCR and Sanger sequencing

In total, 78 samples were genotyped using the new CADMA-based genotyping assays. There was a 100 % accordance between the genotypes of FSHR 307 and FSHR 680. Of the 78 samples, the genotype frequencies for both polymorphisms were 35 % (TT), 42 % (CT), and 23 % (CC), respectively.

Forty-two of the 78 samples were analysed with AS-PCR and 24 of the 78 samples were analysed with Sanger sequencing. As sample material was limited, the 24 samples analysed with sequencing were selected for genotype comparison between the three different genotyping methods (results presented in Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparing results from the CADMA-based assays, AS-PCR and Sanger sequencing

| Sample no. | FSHR 307 CADMA | FSHR 680 CADMA | FSHR 307 AS-PCR | FSHR 680 AS-PCR | FSHR 307 Sequencing | FSHR 680 Sequencing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High quality DNA | 1 | TT | TT | TT | CT | TT | TT |

| 2 | TT | TT | TT | TT | TT | TT | |

| 3 | TT | TT | TT | TT | TT | – | |

| 4 | TT | TT | TT | TT | – | TT | |

| 5 | TT | TT | TT | TT | TT | TT | |

| 6 | TT | TT | TT | TT | poor quality | TT | |

| 7 | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | – | |

| 8 | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | |

| 9 | CT | CT | CT | CT | – | CT | |

| 10 | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | |

| 11 | CT | CT | CT | TT | CT | CT | |

| 12 | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | CT | |

| 13 | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | |

| 14 | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | |

| 15 | CC | CC | CC | CC | – | CC | |

| 16 | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | – | |

| 17 | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | |

| 18 | CC | CC | no amplification | no amplification | CC | CC | |

| Trizol DNA | 19 | TT | TT | TT* | – | TT | TT |

| 20 | TT | TT | TT* | – | poor quality | poor quality | |

| 21 | CT | CT | CT*† | – | poor quality | poor quality | |

| 22 | CT | CT | – | – | poor quality | CT | |

| 23 | CC | CC | CC* | – | CC | CC | |

| 24 | CC | CC | no amplification* | – | poor quality | poor quality |

Discrepancies between assays are highlighted in red

-As sample material was limited, some of the samples could not be tested for all six genotyping assays

*The AS-PCR was performed with an additional + 6 cycles, in order to achieve results for comparison

†The AS-PCR had to be re-run in order to achieve results for comparison

Due to the limited sample material, some of the samples were not tested for all six genotyping assays. As the polymorphisms Thr307Ala and Asn680Ser are in linkage disequilibrium [3, 18, 19] the genotype of the FSHR 307 assays should in theory match the genotype of the FSHR 680 assays. Thus, the samples with limited samples material were analysed for minimum one of the two polymorphisms for each genotyping method, except for sample 22 in which all sample material was used for CADMA-based- and sequencing analysis.

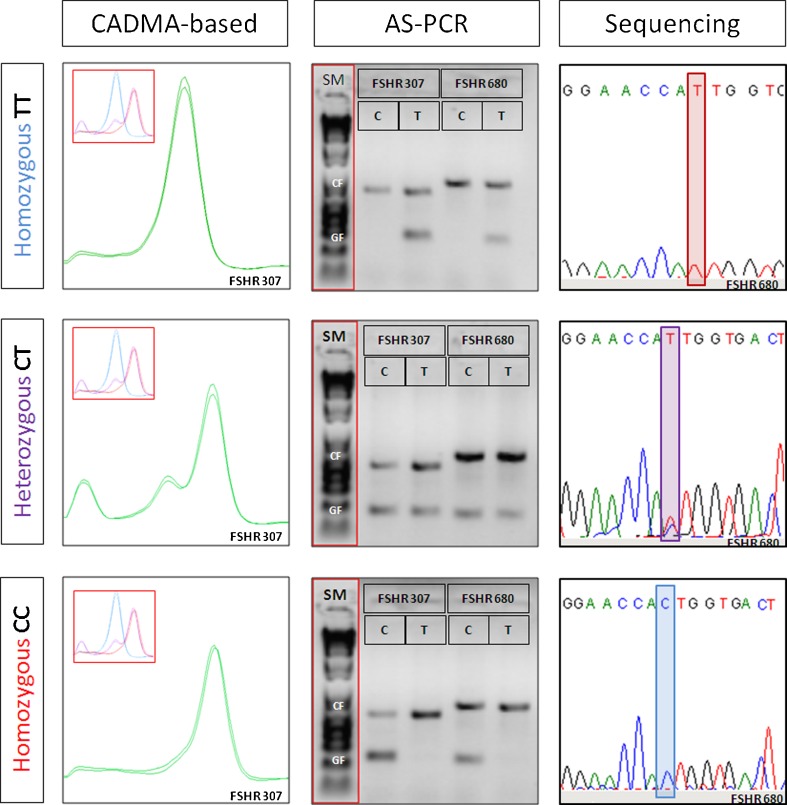

Comparing the results of the three genotyping platforms, there was 100 % accordance between the results of the new CADMA-based assays and the sequencing results. Discrepancies were observed between the results of the new CADMA-based assays and the AS-PCR assays in 2 samples: sample 1 and 11. Since the sequencing results support the genotypes of the CADMA-based assays, the discrepancies were ascribed to false-positive amplification by the AS-PCR assays.

When applying AS-PCR for genotyping, we encountered recurrent problems with uneven amplification and false-positive amplification, as presented in supplementary Fig. S1. Uneven amplification resulted in weak gel-bands, which lowered the analytical sensitivity of the AS-PCR assay. False-positive amplification or uneven amplification occurred at low frequencies, when 50 ng DNA of high quality was used for input in a 50 μl reaction mix. In comparison, no false-positive amplification was observed in the CADMA-based assays. When genotyping trizol extracted DNA (DNA concentration ≤ 10 ng/ul), additional amplification cycles were required (3 to 6 additional cycles) during the PCR to sustain visible gel-bands.

Of the 24 samples selected for comparison between the three genotype methods, the AS-PCR assays failed to genotype 2 samples (sample 18 and 24). Of the total 42 samples analysed with AS-PCR, the AS-PCR assays failed to genotype 3 of the 42 samples, and showed false-positive amplification in 5 of the 42 samples (data not shown). In comparison, the new CADMA-based assays reliably genotyped all 78 samples included in the study.

As expected, the sequencing assays failed to provide useful result for most of the trizol extracted samples, as the DNA of these samples are of low quality and quantities.

Discussion

This paper presents a new, reliable, and simple method for genotyping the two common polymorphisms of the FSHR gene, rs6165 (c.919A > G, p. Thr307Ala, FSHR 307) and rs6166 (c.2039A > G, p. Asn680Ser, FSHR 680).

The two assays are based on a modified version of CADMA, which, by incorporating melting temperature changing mutations in the amplicons, allows for sensitive genotyping by HRM. By applying samples of known genotypes as reference, the melting profiles of the PCR amplicons can be used for reliable genotyping of samples of unknown status. As for AS-PCR, the genotype-specific primers of the two novel CADMA-based assays are designed by including the respective SNPs in the 3’ end of the primer sequences. Unlike AS-PCR, melting temperature increasing mutations are introduced into the amplicons via the primer sequences, to obtain sufficient differences in melting temperatures between the mutated amplicon and the wild-type amplicon (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Because of the introduced mutations in the primers, the amplicons differ in nucleotide content according to genotype. The nucleotide content will be reflected in the melting properties of the amplicon, detectable through HRM analysis.

Besides shifting the melting temperatures of the amplicons, the primer-mismatches against both alleles help to increase the individual primer specificities by increasing the competitive binding between target and primer, thereby limiting false amplification [20]. False positive amplification pose a potential problem when applying conventional AS-PCR for genotyping, as the mutation- and wild-type primers differs only by a single basepair. As for CADMA, an internal mismatch in the primer sequence can however, help to increase the specificity of the primer. An additional limiting factor of the conventional AS-PCR setup is the final identification of the amplicons by gel-electrophoresis. If the final amplicon concentration is low due to low DNA input or sub-optimal PCR conditions, the visibility of the gel-bands may be low or missing. Alternative to gel-electrophoresis, AS-PCR can be performed as real-time PCR and monitored using fluorescent dsDNA binding dyes [21]. As for AS-PCR, conventional PCR followed by HRM has also been applied for SNP genotyping [22]. However, it may be difficult to genotype melting temperature neutral SNPs using this approach [23], and if the PCR has not performed optimally this may cause melting curves to become shifted and potentially lead to false genotyping results [24].

Sanger sequencing and AS-PCR were selected for comparison with the new CADMA-based genotyping assays (Fig. 4). An alternative to the conventional methods is the commercially available TaqMan® assay (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). Although they provide a reliable genotyping platform, the TaqMan® assay was not included in this study, due to the high costs of the assays [25].

Fig. 4.

Methods applied for FSHR genotyping. In the left panel, CADMA-based genotyping analysis is shown with reference peaks in the upper left corners. The three possible genotypes are characterized by distinct melting curves, which enable fast and reliable genotyping. In the mid panel, genotyping by allele specific PCR (AS-PCR) is shown along with a size marker (SM, TrackIt™ 1 KB DNA Ladder, Life technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). Each assay contain a PCR control fragment (CF; upper band) and a genotype specific fragment (GF; lower band), separated by gel-electrophoresis. The presence of a lower band indicates the genotype. In the right panel, genotyping by Sanger sequencing is shown.

We acknowledge that 76 patients included in the present study constitute a relative limited number of patients in the context of a FSHR polymorphism assay. However, it appears that the new assay has several advantages as compared to AS-PCR and sequencing:

Time efficiency

The complete time span from the PCR set-up to the results of the analysis is approximately 2 h for the new assays. For both AS-PCR and Sanger sequencing, considerably longer time spans were required with at least 3 h for AS-PCR and 7 h for sequencing.

Closed-tube analysis

The new assays have the advantage that both PCR and HRM can be performed in the same sealed PCR tube, minimizing the risk of PCR contamination, in contrast to both AS-PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Analysis of fragmented and low input DNA

Although the trizol extracted DNA proved difficult to analyse due to both low DNA yield and poor quality, satisfactory results were obtained for all 28 samples, when applying the CADMA-based genotyping assays. In contrast, adequate results were only obtained in half of the sequenced trizol samples as too much background was present in the electropherograms. Likewise, adequate genotyping results were difficult to obtain by the AS-PCR assays, this however, was partially resolved by increasing the number of PCR cycles and the input DNA.

Interpreting results

Applying standard melting profiles as references, interpreting the results of the new CADMA-based genotyping assays is fast and easy. The AS-PCR method is also easy to interpret, provided that the PCR performs optimally. However, in several of the PCRs the gel-bands were too weak to interpret reliably, which lowers the analytical sensitivity of the AS-PCR assay. Interpreting the results of Sanger sequencing is a bit more time consuming, as additional changes such as insertions or deletions in the DNA sequence may complicate the identification of the SNP of interest.

Costs

The cost for reagents for CADMA-based genotyping is estimated to be roughly one third of the price for sequencing and half cost for conventional Taqman probe assays. We estimate that considerable reduction in cost of FSHR genotyping may encourage a more widespread use of this assay in a clinical IVF setting.

Taken together, the two novel CADMA-based genotyping assays provide a convenient and cost-effective method for genotyping common polymorphisms of the FSHR gene, compared to AS-PCR and Sanger sequencing.

The two new assays presented in this paper are designed to enable genotyping of the prognostic biomarkers Thr307Ala and Asn680Ser, and can be applied to most tissue types, as the FSHR assays enables genotyping of sample inputs down to 0.2 ng, combined with the ability to genotype samples with low DNA quality. The CADMA assay described in this paper should be directly applicable to many diagnostic units, as HRM instruments are standard equipment in most diagnostic laboratories. It is envisioned that this assay should facilitate the use of FSHR genotyping in various clinical situations, as for instance in women receiving low dose stimulation with only limited exogenous FSH administration, where levels of FSH remain in close proximity to the physiological concentrations, contrary to traditional COS where levels of FSH may overshadow potential clinical effects of FSHR polymorphism. Also women who show an unexpected response to COS may be worthwhile to consider for genotyping in order to identify sub-groups where the FSHR polymorphisms may be part of the aetiology.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 176 kb)

False-positive amplification using AS-PCR. We encountered recurrent problems with uneven amplification (left panel) and false-positive amplification (mid and right panel), when genotyping with AS-PCR. Each assay consists of two PCR runs, one for each genotype, containing a PCR control fragment (CF; upper band) and a genotype specific fragment (GF; lower band). The presence of a lower band marks the genotype. As the two polymorphisms are in linkage disequilibrium, the genotype of FSHR 307 should match the genotype of FSHR 680. (GIF 333 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Yvonne Giwercman from Molecular Genetic Reproductive Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden, for providing reference DNA of known genotypes, as well as AS-PCR assays the FSHR polymorphisms rs6165 and rs6166.

Source of funding

This work was supported by the faculty of Health, University of Aarhus, and by ReproHigh, an Interregional EU project.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alviggi C, et al. A common polymorphic allele of the LH beta-subunit gene is associated with higher exogenous FSH consumption during controlled ovarian stimulation for assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alviggi C, Humaidan P, Ezcurra D. Hormonal, functional and genetic biomarkers in controlled ovarian stimulation: tools for matching patients and protocols. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behre HM, et al. Significance of a common single nucleotide polymorphism in exon 10 of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor gene for the ovarian response to FSH: a pharmacogenetic approach to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:451–456. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000167330.92786.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Marca A, et al. Polymorphisms in gonadotropin and gonadotropin receptor genes as markers of ovarian reserve and response in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laan M, Grigorova M, Huhtaniemi IT. Pharmacogenetics of follicle-stimulating hormone action. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19:220–227. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283534b11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoni M, Casarini L. Potential for pharmacogenetic use of FSH: a 2014-and-beyond view. Endocrinol: Eur. J; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai SS, et al. Association of allelic combinations of FSHR gene polymorphisms with ovarian response. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klinkert ER, et al. FSH receptor genotype is associated with pregnancy but not with ovarian response in IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazaros L, et al. Influence of FSHR diplotypes on ovarian response to standard gonadotropin stimulation for IVF/ICSI. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lledo B, et al. Effect of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor N680S polymorphism on the efficacy of follicle-stimulating hormone stimulation on donor ovarian response. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013;23:262–268. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835fe813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez MM, et al. Ovarian response to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation depends on the FSH receptor genotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3365–3369. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y. Association of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor polymorphisms with ovarian response in Chinese women: a prospective clinical study. PLoS.One. 2013;8:e78138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Y, Ma CH, Tang HL, Hu YF. Influence of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) Ser680Asn polymorphism on ovarian function and in-vitro fertilization outcome: a meta-analysis. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudjenah R. Genetic polymorphisms influence the ovarian response to rFSH stimulation in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization programs with ICSI. PLoS.One. 2012;7:e38700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristensen LS, Andersen GB, Hager H, Hansen LL. Competitive amplification of differentially melting amplicons (CADMA) enables sensitive and direct detection of all mutation types by high-resolution melting analysis. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:264–271. doi: 10.1002/humu.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristensen LS, Kjeldsen TE, Hager H, Hansen LL. Competitive amplification of differentially melting amplicons (CADMA) improves KRAS hotspot mutation testing in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindgren I, Giwercman A, Axelsson J, Lundberg GY. Association between follicle-stimulating hormone receptor polymorphisms and reproductive parameters in young men from the general population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:667–672. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283566c42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gromoll J, Simoni M. Genetic complexity of FSH receptor function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La MA, et al. The combination of genetic variants of the FSHB and FSHR genes affects serum FSH in women of reproductive age. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1369–1374. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok S, Chang SY, Sninsky JJ, Wang A. A guide to the design and use of mismatched and degenerate primers. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;3:S39–S47. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.4.S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morlan J, Baker J, Sinicropi D. Mutation detection by real-time PCR: a simple, robust and highly selective method. PLoS.One. 2009;4:e4584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittwer CT, Reed GH, Gundry CN, Vandersteen JG, Pryor RJ. High-resolution genotyping by amplicon melting analysis using LCGreen. Clin Chem. 2003;49:853–860. doi: 10.1373/49.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gundry CN, et al. Base-pair neutral homozygotes can be discriminated by calibrated high-resolution melting of small amplicons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3401–3408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristensen LS, Dobrovic A. Direct genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms in methyl metabolism genes using probe-free high-resolution melting analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1240–1247. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De La Vega FM, Lazaruk KD, Rhodes MD, Wenz MH. Assessment of two flexible and compatible SNP genotyping platforms: TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays and the SNPlex Genotyping System. Mutat Res. 2005;573:111–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casarini L, Pignatti E, Simoni M. Effects of polymorphisms in gonadotropin and gonadotropin receptor genes on reproductive function. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011;12:303–321. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 176 kb)

False-positive amplification using AS-PCR. We encountered recurrent problems with uneven amplification (left panel) and false-positive amplification (mid and right panel), when genotyping with AS-PCR. Each assay consists of two PCR runs, one for each genotype, containing a PCR control fragment (CF; upper band) and a genotype specific fragment (GF; lower band). The presence of a lower band marks the genotype. As the two polymorphisms are in linkage disequilibrium, the genotype of FSHR 307 should match the genotype of FSHR 680. (GIF 333 kb)