Although treatable and curable in many developed countries, tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant health threat and leading cause of death in resource-poor countries. However, the emergence of extensively and multidrug-resistant TB has the potential to also become a significant threat to public health in industrialized nations. Prompted by the limited data regarding the treatment course of multidrug-resistant TB in Canada, this retrospective cohort study examined individual characteristics and responses of a group of patients treated at a health care centre in Toronto, Ontario.

Keywords: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, Outcomes, Review, Treatment

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading cause of death worldwide and the emergence of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) poses a threat to its control. There is scanty evidence regarding optimal management of MDR TB. The majority of Canadian cases of MDR TB are diagnosed in Ontario; most are managed by the Tuberculosis Service at West Park Healthcare Centre in Toronto. The authors reviewed 93 cases of MDR TB admitted from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2011.

RESULTS:

Eighty-nine patients were foreign born. Fifty-six percent had a previous diagnosis of TB and most (70%) had only pulmonary involvement. Symptoms included productive cough, weight loss, fever and malaise. The average length of inpatient stay was 126 days. All patients had a peripherally inserted central catheter for the intensive treatment phase because medications were given intravenously. Treatment lasted for 24 months after bacteriologic conversion, and included a mean (± SD) of 5±1 drugs. A successful outcome at the end of treatment was observed in 84% of patients. Bacteriological conversion was achieved in 98% of patients with initial positive sputum cultures; conversion occurred by four months in 91%.

CONCLUSIONS:

MDR TB can be controlled with the available anti-TB drugs.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La tuberculose (TB) demeure une cause importante de décès dans le monde, et l’émergence de TB multirésistante (TB-MR) en menace le contrôle. Il existe peu de données probantes sur la prise en charge optimale de la TB-MR. Au Canada, la majorité des cas de TB-MR sont diagnostiqués en Ontario, et la plupart sont pris en charge par le service de la tuberculose du West Park Healthcare Centre de Toronto. Les auteurs ont examiné 93 cas de TB-MR hospitalisés entre le 1er janvier 2000 et le 31 décembre 2011.

RÉSULTATS :

Quatre-vingt-neuf patients étaient nés à l’étranger. Cinquante-six pour cent avaient déjà eu un diagnostic de TB, et la plupart (70 %) présentaient uniquement une atteinte pulmonaire. Leurs symptômes incluaient une toux productive, une perte de poids, de la fièvre et des malaises. L’hospitalisation durait en moyenne 126 jours. Tous les patients ont eu un cathéter central inséré par voie périphérique pendant la phase de traitement intensif, car les médicaments étaient administrés par voie intraveineuse. Le traitement a été maintenu 24 mois après la conversion bactériologique et incluait une moyenne (±ÉT) de 5±1 médicaments. Chez 84 % des patients, le résultat était positif à la fin du traitement. Ainsi, 98 % des patients ont profité d’une conversion bactériologique aux cultures d’expectorations initiales positives. Chez 91 % d’entre eux, la conversion s’était produite au bout de quatre mois.

CONCLUSIONS :

Il est possible de contrôler la TB-MR à l’aide des médicaments antituberculeux actuellement sur le marché.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease that is preventable, treatable and curable; however, it remains one of the leading causes of death in the world, primarily in resource-poor countries.

The emergence of drug-resistant TB, multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB poses a significant worldwide threat to the control and treatment of the disease (1–3). As defined by the WHO, MDR TB demonstrates resistance to at least both of isoniazid and rifampicin; extensively drug-resistant TB demonstrates additional resistance to any fluoroquinolone and to at least one second-line injectable agent (capreomycin, kanamycin, amikacin) (4). The increasing proportion of resistant cases is contributing to a risk to public health, with significant morbidity and mortality on a global level, and a significant challenge to public health in industrialized countries (4,5).

Newly diagnosed cases of TB in Canada are both demographically and geographically focused, affecting marginalized individuals, the foreign born and Aboriginal Canadians. The majority of MDR TB cases in Canada are diagnosed in foreign-born individuals from countries with the largest burden of TB. Most newcomers immigrate to large urban centres in Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta, leading to a concentration of TB cases in these areas. The incidence rate of new TB cases in Canada overall is 4.6 per 100,000 population, while in Toronto (Ontario), the rate is >12 per 100,000 (6). Of the TB diagnosed in Canada, 40% of all TB cases and 60% of MDR TB cases are diagnosed in Ontario.

The management of MDR TB is complex, requiring multiple second-line drugs that have lower efficacy against TB, or more frequent or severe side effects than the first-line drugs. The WHO has categorized anti-TB drugs into five groups, with group 1 including the standard oral first-line agents (Table 1) (7,8).

TABLE 1.

Antituberculosis drugs

| Group | Description | Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | First-line oral agents | Isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, rifabutin |

| 2 | Injectable agents | Kanamycin, amikacin, capreomycin, streptomycin* |

| 3 | Fluoroquinolones | Moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, ofloxacin |

| 4 | Oral bacteriostatic second-line agents | Ethionamide, protionamide, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid |

| 5 | Agents with unclear efficacy | Clofazimine, linezolid, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, thiacetazone, clarithromycin, imipenem |

There are limited available data regarding the treatment course of MDR TB in Canada. Therefore, we aimed to describe our experience in treating 93 cases of MDR TB over a 12-year period. We sought to identify patient characteristics associated with early bacteriological response to treatment.

METHODS

Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint Bridgepoint/West Park Healthcare Research Ethics Board, Toronto, Ontario.

A retrospective cohort study was performed. All patients diagnosed with MDR TB at West Park Healthcare Centre between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2011 were included. Patients were identified through chart review.

As standard practice, all patients with MDR TB were admitted to the inpatient TB Service for isolation and initiation of treatment. Sputum cultures were repeated monthly until bacteriologic conversion was achieved. Bacteriologic conversion was defined as three sets of negative sputum cultures (each set comprises two specimens one day apart) for three consecutive months; the date of conversion was defined as the date of collection of the first negative culture. Patients with pulmonary involvement remained in isolation until achieving bacteriologic conversion.

Antibiotic selection and dosing

The intensive phase of treatment lasted six months, while the continuation phase extended 24 months after bacteriologic conversion. All patients had a peripherally inserted central catheter for the duration of the intensive phase. Since 2002, it has been practice to administer all antibiotics by intravenous route, if possible (9,10). Drug combinations were guided by TB in vitro susceptibility testing. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was performed at the Public Health Ontario Laboratories (Toronto, Ontario). DST was performed according to Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute testing standards recommended methods (as available), including agar proportion, radiometric broth (BACTEC 460, Becton-Dickinson, USA) and nonradiometric broth (MGIT 960, Becton-Dickinson, USA) (11–13). Antibiotic dosing is described in Table 2. All first-line drugs to which susceptibility was preserved were used.

TABLE 2.

Drugs used in treatment regimen (n=93)

| Drug | Patients, n (%) | Dose and unique monitoring requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Ethambutol | 41 (44.1) | 15 mg/kg daily. Visual acuity and colour vision assessed monthly in hospital and every 2 months after discharge |

| Pyrazinamide | 36 (38.7) | 20–25 mg/kg daily for first 3 months of therapy |

| Rifabutin | 7 (7.5) | 300 mg daily |

| Streptomycin | 2 (2.2) | 15 mg/kg daily |

| Amikacin | 83 (89.2) | Initial dose 15 mg/kg daily. Adjusted to target serum peak and trough levels of 25–30 mg/L and <2 mg/L, respectively. Audiometry assessed every 1–2 months (17) |

| Capreomycin | 0 (0) | |

| Any fluoroquinolone | 87 (93.6) | |

| Ofloxacin | 3 (3.2) | 400 mg BID |

| Levofloxacin | 15 (16.1) | 750 mg daily. Used since 2005 |

| Gatifloxacin | 25 (26.9) | 400 mg daily. Used until withdrawn from the market |

| Moxifloxacin | 59 (63.4) | 400 mg daily. Used since 2006 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 (1.1) | 500 mg BID |

| Ethionamide | 20 (21.5) | 250 mg BID. Thyroid-stimulating hormone assessed monthly (18) |

| Cycloserine | 30 (32.3) | 250 mg BID |

| Para-aminosalicylic acid | 42 (45.2) | 4 g BID. Thyroid-stimulating hormone assessed monthly (18) |

| Clofazimine | 87 (93.6) | 100 mg daily |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 13 (14.0) | 500/125 mg TID |

| Clarithromycin | 9 (9.7) | 500 mg BID |

| Linezolid | 4 (4.3) | 600 mg BID |

| Imipenem | 4 (4.3) | 1 g BID |

| Thioridazine | 2 (2.2) | 50 mg daily at bedtime |

| Thalidomide | 1 (1.1) | 25 mg daily |

| Drugs in regimen, mean ± SD | 5.0±1.5 |

BID Twice daily; TID Three times daily

Drug monitoring and adverse effects

Patients were closely monitored for side effects, and drug regimens were adjusted as needed (14). Nausea and gastrointestinal upset were managed with antiemetics and proton pump inhibitors. Complete blood counts, creatinine and liver enzyme levels were routinely measured in all patients. If liver enzyme levels were elevated above three times the upper limit of normal, all medications were stopped temporarily; once normalized, the drugs were sequentially reintroduced in increasing order of the potential for hepatotoxicity (15,16). Other drug-specific monitoring steps are described in Table 2 (17,18).

Other management issues

Psychosocial issues were identified through intensive interviews with each patient at admission. Individual and family counselling was conducted regularly and, where appropriate, external referrals were made at discharge. Weekly education/information sessions were conducted for patients and family. Mixed media were used, as well as open-ended group discussions. Because many of our patients did not speak English, the authors used interpretation services heavily, either onsite or by telephone.

Follow-up

After completing the inpatient portion of treatment, all patients with MDR TB were discharged home with community-based directly observed therapy (19), which was administered once daily five days per week. Patients attended TB clinic at two-month intervals until completion of treatment. At each visit, liver enzyme levels, complete blood count and chest radiography were obtained. After treatment completion, patients were seen at six-month intervals for two years and yearly thereafter. Each clinic visit included a review of symptoms, physical examination and chest radiography. Patients with significant lung scarring had computed tomography scans and underwent sputum induction to confirm sustained bacteriologic conversion at yearly intervals.

Data collection and analysis

Demographic and immigration history data were abstracted in addition to clinical and radiographic findings at presentation, comorbidities, drug resistance patterns and treatment course. Data are presented as mean and SD, or number and percentage, as appropriate. Patient and treatment factors associated with a favourable treatment outcome were sought. Because the observed mortality and treatment failure rates were low, the primary outcome was chosen as early bacteriologic conversion within two months of starting MDR TB treatment. Variables studied for an association with early bacteriologic conversion included demographic characteristics, presenting symptoms, comorbidities, presence/absence of resistance for each drug tested and use of each drug in the treatment regimen. Univariate associations were assessed using χ2 and Student’s t test, as appropriate, with a significance level of 0.05. In sensitivity analyses, the cut-off value for early conversion was varied to three and four months. Although multivariate regression analysis was planned, the sample size proved to be too small to permit this to be performed.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

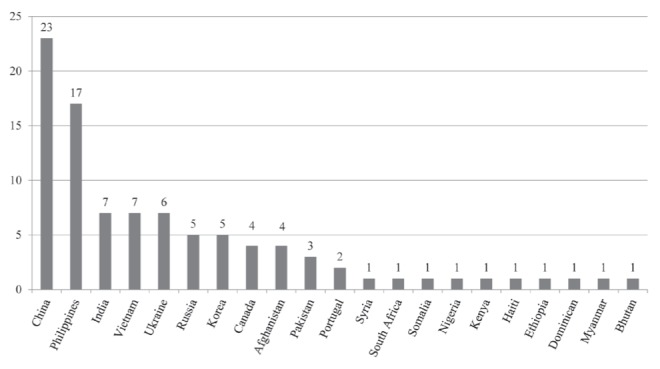

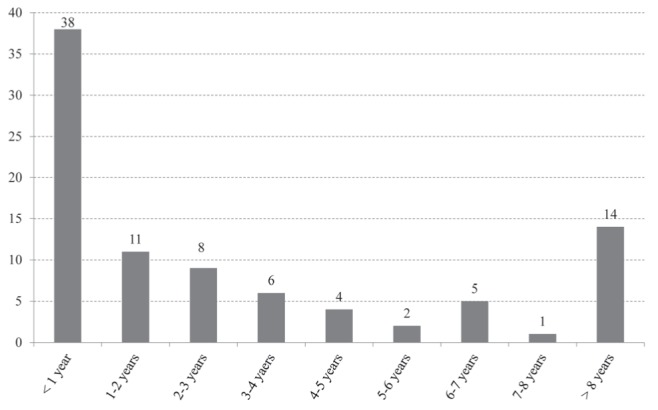

During the study period, 111 patients were diagnosed with MDR TB in Ontario. Of these, 93 (84%) were referred to West Park Healthcare Centre and admitted to the inpatient TB Service. The reason for referral was universally for management of MDR TB. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 3. Forty percent of the patients were female and the mean (± SD) age was 36±15 years. Eighty-nine (96%) were foreign born, most commonly from China and the Philippines (Figure 1). At the time of diagnosis, 43% had been in Canada for <1 year (Figure 2). Of the four Canadian-born individuals, one was Aboriginal, two were Canadian-born children of foreign-born parents; and the fourth had close contact with a foreign-born individual with MDR TB.

TABLE 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 36.0±15.2 |

| Female sex | 37 (39.8) |

| Canadian born | 4 (4.3) |

| Foreign born | 89 (95.7) |

| Landed immigrant | 45 (48.4) |

| Refugee | 22 (23.7) |

| Visitor | 7 (7.5) |

| Work visa | 1 (1.1) |

| Student visa | 4 (4.3) |

| Foreign born, unknown status | 10 (10.8) |

| Years in Canada before MDR TB diagnosis, mean ± SD | 4.6±6.1 |

| Previous TB treatment | 49 (52.7) |

| Symptoms | |

| Productive cough | 56 (60.2) |

| Weight loss | 51 (54.8) |

| Malaise | 36 (38.7) |

| Fever | 37 (39.8) |

| Hemoptysis | 13 (14.0) |

| Night sweats | 17 (18.3) |

| Chest pain | 13 (14.0) |

| Other symptoms | 20 (21.5) |

| Asymptomatic | 18 (19.3) |

| Site of TB | |

| Pulmonary only | 65 (69.6) |

| Pulmonary + extrapulmonary | 16 (17.2) |

| Extrapulmonary only | 12 (12.9) |

| Lymphatic | 15 (16.1) |

| Other sites | 18 (19.4) |

| Comorbidities | |

| HIV | 1 (1.1) |

| Hepatitis B | 3 (3.2) |

| Hepatitis C | 2 (2.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (9.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (5.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (10.8) |

| Psychiatric illness | 7 (7.5) |

| Cancer | 5 (5.4) |

| Heart disease | 6 (6.4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. MDR Multidrug-resistant; TB Tuberculosis

Figure 1).

Multidrug-resistant patients according to country of birth. Note: patients from China include 12 Tibetans

Figure 2).

Length of time in Canada at time of diagnosis (foreign born [n=89])

Most patients were symptomatic, most commonly with productive cough and constitutional symptoms (Table 3). Eighteen patients initially reported no symptoms. Regarding the site of TB, 70% had only pulmonary involvement, 13% had only extrapulmonary involvement, and 17% had both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB (Table 3). The most common extrapulmonary site of involvement was lymphatic (16%). Comorbidities were not common (Table 3) and coinfection with HIV was present in only one patient.

Drug resistance

Four patients presented with resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid only. The remaining 89 patients showed resistance to ≥3 drugs (Table 4). Drugs tested for susceptibilities varied over the study period due to changes in laboratory testing guidelines and practice.

TABLE 4.

Drug resistance

| Drug | Previous treatment for tuberculosis* | New tuberculosis |

|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | 49/49 (100) | 44/44 (100) |

| Rifampin | 49/49 (100) | 44/44 (100) |

| Ethambutol | 28/49 (57.1) | 19/44 (43.2) |

| Pyrazinamide | 20/49 (40.8) | 14/44 (44) |

| Rifabutin | 28/45 (62.2) | 30/39 (76.9) |

| Streptomycin | 33/49 (67.4) | 33/44 (75.0) |

| Amikacin | 3/49 (6.1) | 1/44 (2.3) |

| Capreomycin | 1/49 (2.0) | 2/44 (4.6) |

| Any fluoroquinolone | 8/49 (16.3) | 2/44 (4.6) |

| Ofloxacin | 8/49 (16.3) | 2/44 (4.6) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0/0 (0) | 0/1 (0) |

| Moxifloxacin | 0/2 (0) | 0/2 (0) |

| Ethionamide | 13/49 (26.5) | 13/44 (29.6) |

| Para-aminosalicylic acid | 0/18 (0) | 2/22 (9.1) |

| Clofazimine | 0/46 (0) | 1/42 (2.4) |

| Linezolid | 0/2 (0) | 0/2 (0) |

| Drugs resistant, n | ||

| 2 | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 8 (16.3) | 10 (22.7) |

| 4 | 12 (24.5) | 13 (29.6) |

| 5 | 9 (18.4) | 7 (15.9) |

| 6 | 8 (16.3) | 10 (22.7) |

| 7 | 5 (10.2) | 4 (9.1) |

| 8 | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) |

| Drugs resistant, mean ± SD | 4.7±1.7 | 4.7±1.3 |

| XDR tuberculosis | 0 (0)† | 0 (0) |

Data presented as number resistant/number tested (%) or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Patient self-report of previous tuberculosis (TB) treatment;

One patient presented to the authors institution initially with multidrug-resistant TB plus fluoroquinolone resistance but stopped treatment and was lost to follow-up after five months of treatment. He presented again to the authors’ institution one month after being ‘lost’, was again culture positive and had developed amikacin resistance (extensively drug-resistant [XDR] TB), which was successfully treated

Treatment

Patients were hospitalized for 126±71 days; the total treatment duration averaged 26±7 months. Regimens included a mean of 5.0±1.5 drugs (Table 2). The most common combination included at least amikacin, a fluoroquinolone and clofazimine.

Outcomes

All patients completed treatment at the time of writing. Sixty patients continue to be followed in clinic; the longest follow-up to date is eight years following treatment completion. Eighty-four percent of patients had a successful outcome at the end of treatment (cure or treatment completed) (Table 5) (20). Three patients died, but two of these were from causes unrelated to MDR TB (liver cancer and suicide). The cause of death in the third patient was unknown because he was transferred to another institution, but may have been due to MDR TB. One patient failed treatment and one was lost to follow-up (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Treatment outcomes (n=93)

| Outcome at end of treatment* | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cure or treatment completed | 78 (83.9) |

| Death | 3 (3.2)† |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 (1.1) |

| Treatment failure | 1 (1.1) |

| Not evaluated | 10 (10.8) |

| Outcome after treatment | |

| Possible relapse | 3 (3.2) |

| Microbiologically confirmed relapse | 0 (0) |

As defined by the WHO (20);

Two deaths were unrelated to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

All patients experienced clinical improvement, including those who reported no symptoms when initially assessed; all 93 (100%) patients gained weight. Bacteriologic conversion was achieved in 79 of 81 (98%) patients with initial positive sputum cultures. One patient died from metastatic liver cancer before treatment was implemented, and the other patient’s treatment outcome was unknown because this patient was transferred to another institution before conversion. Sputum cultures were negative in 52 (66%) patients by two months after treatment implementation; in 68 (86%) by three months; and in 72 (91%) by four months. Two (2.2%) patients achieved culture conversion; however, their sputa subsequently became positive again. One of these patients reverted because of nonadherence to treatment (lost to follow-up). The other patient was classified as a treatment failure. This patient achieved bacteriologic conversion after two months of treatment, but had worsening imaging and positive sputum cultures after 17 months of treatment. Her initial isolate was resistant to fluoroquinolones; however, the drug susceptibility did not change. Once she achieved bacteriologic conversion again, she underwent right upper lobectomy and has remained free from disease since 2010.

Of the 93 patients, there were three (3.2%) possible relapses but no microbiologically confirmed relapses (Table 5). One patient presented with pulmonary and extrapulmonary (cervical lymphatic) disease and completed 24 months of treatment following bacteriological conversion. A fluoroquinolone was given for only two months due to severe Achilles tendonitis. Eight months after treatment completion, a new enlarged cervical lymph node developed; biopsy of the lymph node showed necrotizing granulomas, but bacteriologic testing was negative. Treatment was restarted and she recently completed 26 months of retreatment. The second patient with possible relapse had pulmonary MDR TB and achieved culture conversion after two months of treatment. Three months after completing 26 months of treatment, she had a new infiltrate on chest x-ray and MDR TB treatment was reinitiated. Bronchoscopy was smear and culture negative but did not reveal another etiology for the infiltrate. Retreatment for MDR TB was completed after 36 months. The third possible relapse had pulmonary and cervical lymphatic MDR TB; culture conversion was achieved at four months of treatment and he completed 28 months of treatment. One month after treatment completion, new cervical lymphadenopathy developed and MDR TB treatment was reinitiated; the lymphadenopathy quickly resolved. An excisional biopsy was performed after four months of treatment (a biopsy could not be obtained sooner), but cultures were negative and pathology was inconclusive. Treatment was discontinued after nine months because of transaminitis and was not restarted. He was free from disease for the three subsequent years of follow-up.

Predictors of early culture conversion

Patients whose regimen included ethionamide were significantly more likely to convert within two months of initiating therapy than those who did not (87% versus 60%; P=0.040). However, when the outcome was examined as conversion within three or four months, no significant association was found. Patients without a productive cough were more likely to achieve early bacteriologic conversion than those who had a productive cough (81% versus 58%; P=0.049), but again, there was no association with conversion at three or four months. No other single medication use, drug susceptibility or patient characteristic was found to be significantly associated with early conversion.

DISCUSSION

In the present retrospective review of 93 MDR TB patients treated at West Park Healthcare Centre, we found that 84% of patients achieved a successful outcome at the end of treatment. When potential relapses are included (n=3), 81% of patients achieved a successful treatment outcome. Furthermore, sputum culture conversion occurred quickly in most patients with pulmonary MDR TB; conversion occurred by two months of therapy in 66% of patients and by four months in 91%. We could not identify any factors that predicted early conversion. An overall modest sample size and the comparatively few poor outcomes limited our ability to perform multivariable analyses.

Other Canadian studies reporting treatment outcomes in MDR TB include a report describing 24 cases treated in Alberta or British Columbia from 1989 to 1998 (21), an earlier cohort from our institution (22) and a recently published nationwide public health surveillance study (23). The Western Canada study observed a successful outcome in eight of 18 (44%) patients who had completed treatment at time of writing. Four patients had nonevaluable outcomes. Five of 24 (20%) patients died, a significantly higher proportion than the 3.2% that we observed. The explanation for this difference is not readily apparent, but may be due to the age difference between the two patient populations: mean age 52±19 years in the Western Canada cohort versus 36±15 years in our cohort. Another possible explanation for the difference in outcomes is that our cohort was treated one decade later and treatment of MDR TB has evolved. The more recent nationwide public health surveillance study reported treatment outcomes of 91 MDR TB cases from 1997 to 2008 (23). A successful outcome was observed in 65 of 91 (71%) of patients, death occurred in six of 91 (6.6%) and a negative outcome (death, failure, lost to follow-up or treatment ongoing for >3 years) was observed in 19 of 91 (21%). The treatment outcomes observed at our institution are similar to – but still somewhat more favourable – than these Canada-wide treatment outcomes.

Treatment outcomes at our institution from 2000 to 2011 were better than those observed in patients treated from 1986 to 1999; success was 70% in the earlier cohort (22). This improvement in treatment outcomes over time has also been described by another institution (24). Chan et al (24) found that their long-term success rate was 75% for patients treated from 1984 to 1998, versus 56% for those treated from 1973 to 1983. They surmised that the improvement in outcomes was due to increased use of resectional lung surgery and fluoroquinolones.

We also suspect that the evolution of fluoroquinolone use may have played a role in our higher success rate. From 1986 to 1999, we used ciprofloxacin (an earlier-generation fluoroquinolone) in 65% of patients; no other fluoroquinolones were used. From 2000 to 2011, a fluoroquinolone was used in 94% of patients, and the most commonly used drugs of this class were moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin (both later-generation fluoroquinolones). Meta-analyses have shown that the use of a fluoroquinolone in an MDR TB regimen is associated with better outcomes (25,26). Additionally, later-generation fluoroquinolones have been shown to have superior bactericidal activity compared with earlier-generation fluoroquinolones (27). Because nearly all of our patients were treated with a fluoroquinolone, we were unable to demonstrate statistically significant effects on treatment outcomes.

Resectional lung surgery did not play a role in our increase in successful outcomes. Some experts have recommended surgical treatment for patients with well-localized disease who have sufficient respiratory function and in whom there are a lack of sufficient available drugs to design a curative regimen (9). However, only one of our patients fulfilled this criterion and underwent successful right upper lobectomy. In our earlier cohort, six of 40 (15%) patients underwent lung resection surgery.

The relatively high rate of successful outcomes that we observed was likely due to several key aspects of our treatment approach. We treated patients for >18 months, and we used directly observed therapy throughout; this combination of strategies is associated with better outcomes (28). We used at least four likely effective drugs in the intensive phase, another strategy associated with success (26). We used an individualized treatment strategy whereby second-line DST was used to design treatment regimens. This is in contrast to standardized drug regimens used by some programs that are based on population surveys of local drug-susceptibility patterns. There are limited data comparing individualized and standardized treatment regimens; however, one systematic review showed higher treatment success with individualized regimens (64%) than standardized regimens (54%), although the difference was not significant (28).

We also used a multidisciplinary team to manage our MDR TB patients, whereby we addressed both medical and psychosocial issues. Ninety-six percent of our patients were foreign born; most were in Canada <5 years, and they were in various stages of establishing themselves and their families. In Canada, it is well documented that immigrants and refugees take seven to 10 years to achieve economic stability, and at least one-third of newcomers live in officially defined poverty during their first 10 years of resettlement (29,30). Additionally, we have observed that the respiratory isolation associated with MDR TB treatment presents multiple challenges for both the patient and his/her family. TB patients are vulnerable to the stigma associated with a diagnosis of TB within their respective ethnocultural communities. Ethnicity, health care beliefs, familiarity with the Canadian health care system, language barriers, literacy, cultural and religious beliefs, educational level and socioeconomic status potentially affect the health outcomes of MDR TB patients (31). Timely and careful monitoring for psychiatric side effects, with medications and multidisciplinary psychosocial interventions, have been successful strategies in treating and managing our patients (30).

Several aspects of our treatment approach may be considered controversial. We hospitalized all patients for initiation of treatment until they were deemed to be no longer infectious; the average length of stay was 126 days. The WHO currently recommends an ambulatory-based model of care over a hospitalization-based model because of improved cost effectiveness with the former (8). Ours is a mixed-model because the majority of our patients’ treatment still occurs in the outpatient setting. We believe that the initial period of hospitalization is beneficial because it allows for effective isolation, introduction of medications, initial monitoring and management of side effects and support for psychosocial issues.

Our frequent use of clofazimine in the treatment of MDR TB may also be considered controversial because the WHO considers clofazimine to be a group 5 drug. However, two recent systematic reviews have suggested that treatment outcomes with clofazimine-containing regimens are similar to treatment outcomes with more traditional MDR TB regimens (32,33). Additionally, our experience has demonstrated that clofazimine is usually very well tolerated – a finding that is supported by the literature (32). High-quality studies investigating clofazimine containing regimens for the treatment of MDR TB are needed.

Limitations of our study include the fact that it was conducted at a single institution and, therefore, may be subject to referral bias. Additionally, we did not systematically collect data on treatment-related adverse effects.

In summary, our findings indicate that MDR TB can be controlled with the correct combination of available anti-TB drugs used by an experienced team of health care providers.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zignol M, Hosseini M, Wright A, et al. Global incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Infec Dis. 2006;194:479–85. doi: 10.1086/505877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee R, Allen J, Westenhouse J, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in California: 1993–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:450–7. doi: 10.1086/590009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migliori G, Sotgiu G, Lange C, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: Back to the future. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:476–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00025910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2012. < www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/> (Accessed November 15, 2012)

- 5.Langlois-Klassen D, Wooldrage K, Manfreda J, et al. Piecing the puzzle together: Foreign-born tuberculosis in an immigrant receiving country. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:895–902. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada. Tuberculosis in Canada. 2011 < www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tbpc-latb/pubs/tbdrc-ratb11/index-eng.php> (Accessed November 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: Emergency update 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: 2011 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caminero JA. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Evidence and controversies. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:829–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke MF, Appleton SC, Mitnick CD, et al. Aggressive regimens for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis reduce recurrence. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:770–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M24-A2. 2nd edn. Wayne: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; 2011. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes: Approved standard. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NCCLS. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes: Approved standard Document M24-A. Wayne: NCCLS; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCCLS. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes, 2nd edn – Tentative standard NCCLS document M24-T2. Wayne: NCCLS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torun T, Gungor G, Ozmen I, et al. Side effects associated with the treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1372–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts CH, Smith C, Breen R, et al. Hepatotoxicity in the treatment of tuberculosis using moxifloxacin-containing regimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1275–6. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, Shin SS, et al. Hepatotoxicity during treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Occurrence, management and outcome. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:596–603. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seddon JA, Godfrey-Fausset P, Jacobs K, et al. Hearing loss in patients on treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1277–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00044812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satti H, Mafukidze A, Jooste PL, et al. High rate of hypothyroidism among patients treated for multidrug-resistant in Lesotho. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:468–72. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toczek A, Cox H, Du Cros P, et al. Strategies for reducing treatment default in drug-resistant tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;17:299–307. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis: 2013 revision. Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersi A, Elwood K, Cowie R, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Alberta and British Columbia, 1989 to 1998. Can Respir J. 1999;6:155–60. doi: 10.1155/1999/456395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avendano M, Goldstein RS. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Long term follow-up of 40 non-HIV-infected patients. Can Respir J. 2000;7:383–9. doi: 10.1155/2000/457905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minion J, Gallant V, Wolfe J, Jamieson F. Multidrug and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Canada 1997–2008: Demographic and disease characteristics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan ED, Laurel V, Strand MJ, et al. Treatment and outcome analysis of 205 patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1103–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1159OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston JC, Shahidi NC, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahuja SD, Ashkin D, Avendano M, et al. Multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis treatment regimens and patient outcomes: An individual patient data meta-analysis of 9,153 patients. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsburg AS, Grosset JH, Bishai WR. Fluoroquinolones, tuberculosis, and resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:432–42. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shan NS, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:153–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beiser M. Resettling refugees and safeguarding their mental health: Lessons learned from The Refugee Resettlement Project. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2009;46:539–83. doi: 10.1177/1363461509351373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mckenzie K, Hansson E, Tuck A, Lam J, Jackson F. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups; issues and options for service improvement. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Achar JM, Sherpa T, Cohen HW, et al. Differences in clinical presentation among persons with pulmonary tuberculosis: A comparison of documented and undocumented foreign-born versus US-born persons. Clin Inf Dis. 2008;47:1277–83. doi: 10.1086/592572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dey T, Bridgen G, Cox H, et al. Outcomes of clofazimine for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:284–93. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopal M, Padayatchi N, Metcalfe JZ, et al. Systematic review of clofazimine for the treatment of drug resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:1001–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]