Abstract

Purpose

Despite earlier detection and stage migration, seminal vesicle invasion is still reported in the prostate specific antigen era and remains a poor prognostic indicator. We investigated outcomes in men with pT3b disease in the contemporary era.

Materials and Methods

The institutional radical prostatectomy database (1982 to 2010) of 18,505 men was queried and 989 with pT3b tumors were identified. The cohort was split into pre-prostate specific antigen (1982 to 1992), and early (1993 to 2000) and contemporary (2001 to present) prostate specific antigen eras. Of the 732 men identified in the prostate specific antigen era 140 had lymph node involvement and were excluded from study. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine biochemical recurrence-free, metastasis-free and prostate cancer specific survival. Proportional hazard models were used to determine predictors of biochemical recurrence-free, metastasis-free and cancer specific survival.

Results

In the pre-prostate specific antigen, and early and contemporary prostate specific antigen eras, 7.7%, 4.3% and 3.3% of patients, respectively, had pT3bN0 disease (p >0.001). In pT3bN0 cases, the 10-year biochemical recurrence-free survival rate was 25.8%, 28.6% and 19.6% (p = 0.8), and the cancer specific survival rate was 79.9%, 79.6% and 83.8% (p = 0.6) among the eras, respectively. In pT3bN0 cases in the prostate specific antigen era, prostate specific antigen, clinical stage T2b or greater, pathological Gleason sum 7 and 8–10, and positive surgical margins were significant predictors of biochemical recurrence-free survival on multivariate analysis while clinical stage T2c or greater and Gleason 8–10 were predictors of metastasis-free and cancer specific survival.

Conclusions

Despite a decreased frequency of pT3b disease, and lower rates of positive surgical margins and lymph nodes, patients with seminal vesicle invasion continue to have low biochemical recurrence-free survival. Advanced clinical stage, intermediate or high risk Gleason sum at pathological evaluation and positive surgical margins predict biochemical recurrence. High risk clinical stage and Gleason sum predict metastasis-free and cancer specific survival.

Keywords: prostate, adenocarcinoma, seminal vesicles, prostatectomy, prostate-specific antigen

Taditionally, SVI by adenocarcinoma of the prostate at RP is associated with worse pathological features and prognosis.1,2 In the PSA era, despite earlier detection and stage migration, rates of SVI have decreased from greater than 10%, but persist at approximately 6% of all RP specimens.3 In-depth studies of pathological specimens have distinguished certain types of SVI, with lesser degrees having more a favorable prognosis.4,5 In the PSA era, SVI is most commonly via extraprostatic extension into the soft tissues adjacent to the prostate and SVs, and subsequently into the wall of the SVs.4 Nevertheless, SVI is believed to be associated with occult micrometastatic disease, earlier biochemical recurrence and eventual disease progression.6

The largest previous analysis of SVI included approximately 300 men and demonstrated a biochemical recurrence rate of greater than 60%.7 A second analysis of 220 men similarly demonstrated a high rate of recurrence (54%) and no benefit to adjuvant or salvage therapy.3 Using a larger, comprehensive database from our institution, we investigated outcomes in men with pT3b disease treated predominantly without ART in the contemporary era.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The institutional review board approved, Johns Hopkins University RP database (1982 to present) was queried for men with pT3b disease. Of approximately 18,505 men who underwent RP 989 had SVI (pT3b disease). All patients at our institution undergo bilateral pelvic LN dissection. All RP specimens were processed. The SVI diagnosis was confirmed under standard protocol with SVI defined as tumor invading the muscular wall of the SV, which can occur by several mechanisms, of which the most common is extraprostatic extension at the base of the prostate, direct tracking along the ejaculatory duct complex, or via isolated, noncontiguous SV deposits.4,8–10 Of note, the route of invasion was not consistently documented and not considered in analysis. The cohort was grouped into 3 time based cohorts, including the prePSA (1982 to 1992), early PSA (1993 to 2000) and contemporary PSA (2001 to 2010) eras. The split between the early and contemporary PSA eras was based on the penetrance of PSA screening and incorporation of the Partin tables into clinical practice at our institution.11,12 A total of 257 men underwent RP before 1993 and 732 were identified in the PSA era, including 283 in the early and 447 in the contemporary eras, respectively. Appropriate comparative tests (the t and chi-square tests, and ANOVA) were used to determine differences in preoperative and postoperative characteristics among the eras.

Men with prostate cancer involving pelvic LNs were excluded from further survival analysis. A total of 242 men with LN invasion (N1) were excluded, yielding 155, 217 and 375 evaluable in each era, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine BFS, MFS and CSS among all 3 time cohorts. Men with pT3bN0 disease in the PSA era only were evaluated for predictors of BFS, MFS and CSS using univariate and multivariate proportional hazard models. Variables included preoperative PSA (0 to less than 10, 10 to less than] 20, and 20 or greater), clinical stage (cT2a or less, cT2b, and cT2c or greater), pathological Gleason sum (2–6, 7, and 8–10) and positive SMs. Significant predictors of BFS, MFS and CSS on univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 989 men were identified with SVI (pT3b). The SVI rate was 12.7%, 5.7% and 3.9% in the prePSA, and early and contemporary PSA eras, respectively (p <0.001). Table 1 lists clinical and pathological data on all patients among the eras. Based on D'Amico criteria,13 the rate of high risk prostate cancer decreased significantly as the era progressed (58.5%, 21.9% and 11.8%, respectively, p <0.001). Of note, the rate of positive SMs decreased from 52.7% to 41.4% to 35.1%, and the rate of positive LNs decreased from 39.7% to 23.9% to 16.1% among the eras, respectively (p <0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and pathological data on all patients with SVI (pT3b) in prePSA, early PSA and contemporary PSA eras

| 1982-1992 | 1993-2000 | 2001-Present | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts | 257 | 285 | 447 | |

| Median age (range) | 61 (38-75) | 59 (41-73) | 59 (40-73) | 0.2 |

| No. race (%): | 0.02 | |||

| Black | 7 (2.7) | 22 (7.7) | 65 (14.5) | |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.7) | |

| White | 248 (96.5) | 250 (87.7) | 363 (81.2) | |

| Other/unknown | 2 (0.8) | 13 (4.6) | 16 (3.6) | |

| No. RP (%): | <0.001 | |||

| Laparoscopic | 0 | 0 | 28 (6.3) | |

| Robot assisted laparoscopic | 0 | 0 | 38 (8.5) | |

| Retropubic | 257 (100.0) | 285 (100.0) | 380 (85.0) | |

| No. clinical stage (%): | <0.001 | |||

| T1a-T2a | 35 (14.2) | 106 (37.5) | 242 (55.5) | |

| T2b | 56 (22.7) | 78 (27.6) | 89 (20.4) | |

| T2c-T3 | 155 (62.8) | 99 (35.0) | 105 (24.1) | |

| Median ng/ml PSA (range) | 12.6(0.6-151) | 9.7 (0.1-84) | 7.2 (0.8-67) | <0.001 |

| No. biopsy Gleason (%): | <0.001 | |||

| 2-6 | 110 (45.5) | 119 (41.9) | 114 (25.6) | |

| 7 | 87 (36.0) | 134 (47.2) | 240 (53.8) | |

| 8-10 | 45 (18.6) | 31 (10.9) | 92 (20.6) | |

| No. pathological Gleason (%): | <0.001 | |||

| 2-6 | 25 (9.7) | 31 (11.0) | 36 (8.1) | |

| 7 | 128 (49.8) | 174 (61.5) | 240 (53.8) | |

| 8-10 | 104 (40.5) | 78 (27.6) | 170 (38.1) | |

| No. pos pathological findings (%): | ||||

| SM | 135 (52.5) | 118 (41.4) | 156 (35.1) | <0.001 |

| LN | 102 (39.7) | 68 (23.9) | 72 (16.1) | <0.001 |

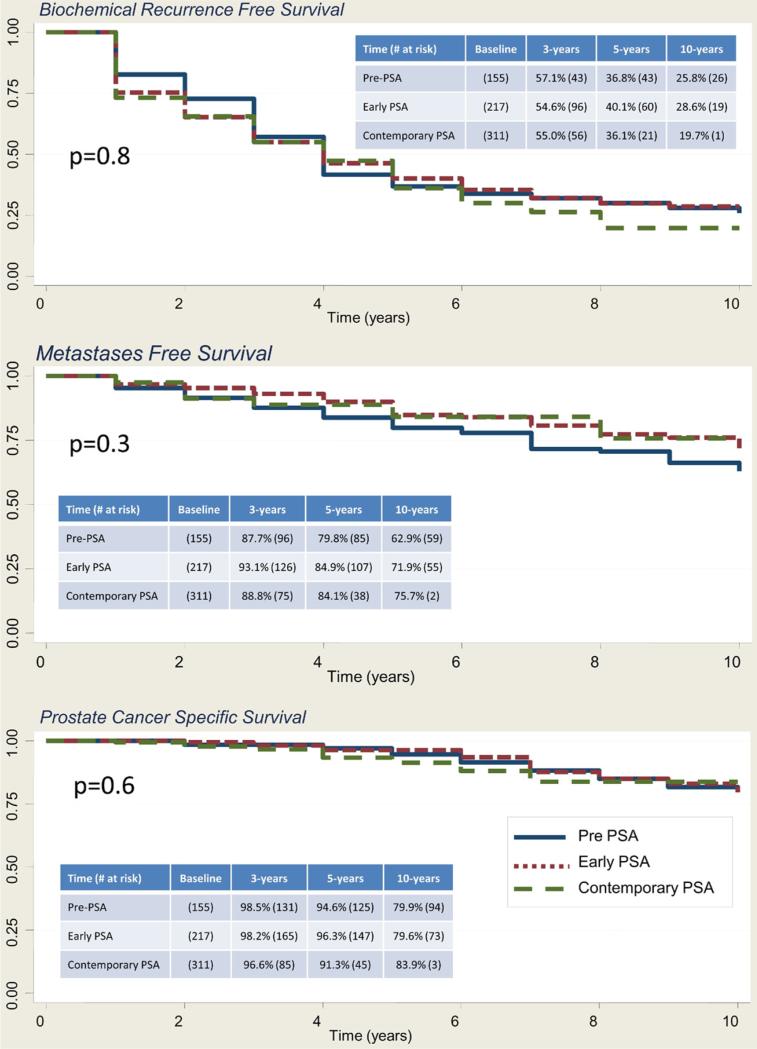

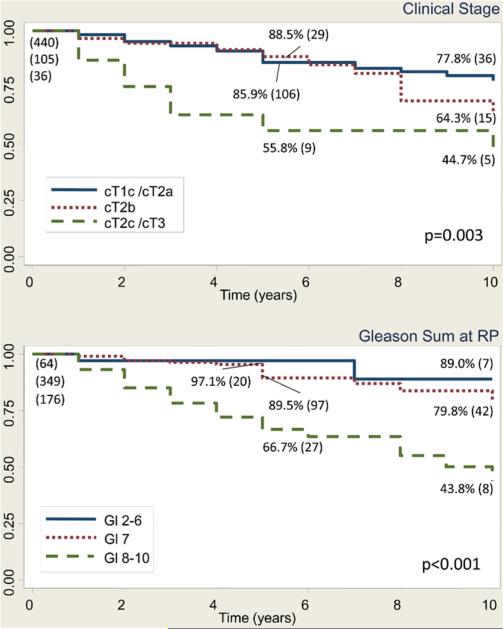

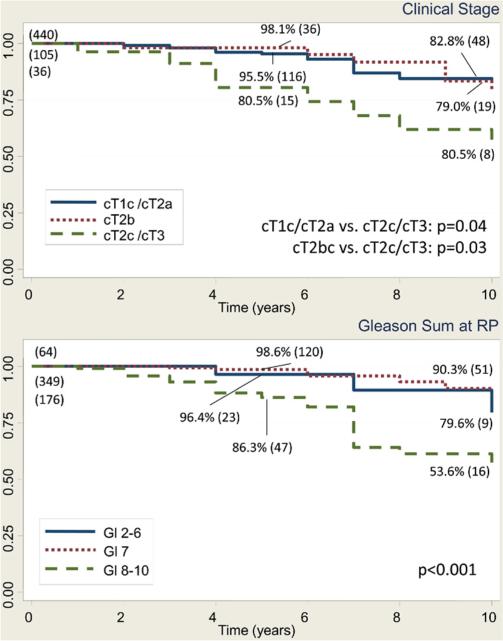

In men with pT3bN0 disease, the 10-year BFS rate was 25.8%, 28.6% and 19.7% in the prePSA, and the early and contemporary PSA eras, respectively (p = 0.8). The MFS rate was 62.9%, 71.9% and 75.7% (p = 0.3), and the CSS rate was 79.9%, 79.6% and 83.9%, respectively (p = 0.6, fig. 1). Table 2 lists the characteristics of the 592 patients with a median age of 59 ears (range 41 to 73) who had pT3bN0 disease and median PSA 7.7 ng/ml (range 0.1 to 84.1). Notably 202 men (34.2%) had positive SMs. In pT3bN0 cases in the PSA era, preoperative PSA (0 to less than 10, 10 to less than 20, and 20 or greater ng/ml), clinical stage (cT2a or less, cT2b, and cT2c or greater), pathological Gleason sum (2 to 6, 7, and 8 to 10) and positive SMs were significant predictors of BFS, MFS and CSS on univariate analysis, and were included in the final multivariate model. Multivariate analysis revealed that clinical stage cT2c or greater (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.08–2.51, p = 0.02), pathological Gleason 7 (HR 14.4, 95% CI 6.9–29.9, p <0.001), and 8–10 (HR 45.3, 95% CI 21.3–96.4, p <0.001) and positive SMs (1.42, 1.11–1.82, p = 0.006) were significant predictors of BFS. Figure 2 shows univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis. Predictors of MFS were clinical stage T2c–T3 (HR 4.3, 95% CI 1.94 –9.3, p <0.001) and Gleason 8 –10 at RP (HR 7.4, 95% CI 1.8 –31.4, p = 0.01, fig. 3). Predictors of CSS were clinical stage T2c–T3 (HR 4.1, 95% CI 1.8 –9.3, p <0.001) and Gleason 8 –10 at RP (HR 3.9, 95% CI 1.35– 11.5, p = 0.01, fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of BFS, MFS and CSS in men with pT3bN0 disease, including survivors and those at risk at 3, 5 and 10 years, in prePSA, early PSA and contemporary PSA eras. Log rank test p value.

Table 2.

Demographic and pathological data on 592 men with pT3bN0 disease in PSA era of 1993 or thereafter

| No. Pts (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race: | |

| Black | 78 (13.2) |

| Asian | 2 (0.3) |

| White | 487 (82.3) |

| Other/unknown | 25 (4.2) |

| RP: | |

| Laparoscopic | 26 (4.4) |

| Robot assisted laparoscopic | 37 (6.3) |

| Retropubic | 528 (89.2) |

| Clinical stage: | |

| cT1a-T2a | 440 (75.7) |

| T2b | 105 (18.1) |

| T2c-T3 | 36 (6.2) |

| Biopsy Gleason: | |

| 2-6 | 203 (34.4) |

| 7 | 297 (50.3) |

| 8-10 | 90 (15.3) |

| Pathological Gleason: | |

| 2-6 | 64 (10.9) |

| 7 | 349 (59.3) |

| 8-10 | 176 (29.9) |

| Pathological findings: | |

| Extraprostatic extension | 512 (86.8) |

| Pos SM | 202 (34.2) |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of BFS in men with pT3bN0 prostate cancer in PSA era, including those with ART or salvage therapy, shows survivors at 5 and 10 years, and number at risk (values in parenthesis). Gl, Gleason. Log rank test p value.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of MFS in men with pT3bN0 prostate cancer in PSA era, including those with ART or salvage therapy, shows survivors at 5 and 10 years, and number at risk (values in parenthesis). Gl, Gleason. Log rank test p value.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of CSS in men with pT3bN0 prostate cancer in PSA era, including those with ART or salvage therapy, shows survivors at 5 and 10 years, and number at risk (values in parenthesis). Gl, Gleason. Log rank test p value.

In the contemporary PSA era, 30 men with pT3bN0 (5.1%) received ART, including 19 with positive SMs. A total of 141 men (41.1%) received adjuvant or salvage radiation (73 or 21.5%), hormone therapy (96 or 28.2%) and/or chemotherapy (29 or 8.9%). When the 144 patients who received adjuvant or salvage therapy were excluded, multivariate analysis including the same variables as before indicated that pathological Gleason sum 8–10 (HR 4.7, 95% CI 1.6–13.6, p = 0.004) and positive SMs (HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.4–4.3, p = 0.001) were predictors of BFS. In general, patients receive salvage therapy upon evidence of metastatic disease at our institution. Therefore, meaningful conclusions could not be drawn from analyses of MFS and CSS when treated patients were excluded.

DISCUSSION

By detecting prostate cancers at an earlier, more curable stage and allowing urologists to better select patients for RP through predictive nomo-grams such as the Partin tables, PSA changed the treatment and outcomes in men with prostate cancer. Consequently, fewer men have advanced grade14 or stage15 at RP. Specifically, prior studies have demonstrated and this study corroborates a decrease in the SVI rate in men who undergo RP. While the rate of SVI (pT3bN0) has more than halved from 7.%7 to 3.6%, SVI remains a strong predictor of biochemical recurrence and cancer specific mortality.7,16

In fact, despite improved detection of prostate cancer through PSA screening, the rates of biochemical recurrence, MFS and CSS in men with pT3b disease have remained remarkably stable from the prePSA to the contemporary eras. This finding is perplexing since preoperative characteristics, such as clinical stage and PSA, the node positive disease rate and positive SM status, appeared to improve as the era of surgery progressed. However, Gleason sum at biopsy and in the pathological specimen may explain the discrepancy between improved screening and earlier detection without an apparent survival advantage. Almost 20% of the men in the contemporary PSA era with pT3b disease had biopsy Gleason sum 8–10, and almost 40% had Gleason 8–10 at RP analysis. These values approximate the rates of advanced grade disease in the prePSA era. While this represents the experience at a single, large tertiary referral center and may be biased by referral patterns, we postulate that the improvements in clinical stage, PSA and pathological stage prompted by PSA screening (as manifested by the decreasing rate of pT3b disease) are offset by the relatively stable proportion of men with high risk Gleason sum in the pT3b population.

Eggener et al reported similar improvements in clinical stage, preoperative PSA and positive SMs between the prePSA and PSA eras, and a concomitant increase in pathological Gleason grade.3 However, they noted improvements in BFS and CSS in the contemporary PSA era at 4 and 7 years that were not seen in our analysis. The improvement in BFS and CSS in their study was only seen on uni-variate analysis of era. When era was evaluated on multivariate analysis, controlling for PSA, Gleason, stage, etc, there was no difference in BFS among the eras, leading the group to conclude that PSA era may act as a “surrogate measure for other prognostic clinical and pathological parameters.”3

The factors most likely to predict biochemical recurrence were advanced clinical stage (greater than T2b), intermediate7 or high risk8–10 pathological Gleason sum, and positive SMs. Multiple series have demonstrated that preoperative PSA, Gleason sum and SM positivity predict BFS.1,6,7,17 PSA was not an important predictor of outcome on multivariate analysis, most likely since our approach focused more directly on the PSA era, so that PSA levels were truncated by improved screening and detection. An earlier analysis from our institution confirmed the importance of Gleason sum and SM status in predicting BFS.18 Importantly, high risk clinical stage and Gleason sum were predictors of MFS and CSS in this cohort, which is valuable information when counseling patients found to have SVI at RP.

The earlier study from our institution also concluded that SVI is not uniformly associated with a poor prognosis. While most men experience biochemical recurrence, patients can be counseled that most will survive many years despite prostate cancer growth beyond the gland. In fact, we observed favorable MFS and CSS rates of 70% and 80%, respectively, at 10 years in men with pT3bN0 disease. Eggener et al similarly found that 80% to 93% of men with SVI were alive at 7 years.3 In the Southwest Oncology Group 8794 study of a cohort of men with pT3N0M0, the MFS and CSS rates at 10 years were 71% and 74% in the groups receiving ART, and 61% and 66%, respectively, in the groups not receiving ART.19 By comparison, only 5% and 40% of men in our analysis went on to receive adjuvant radiation and salvage treatments, respectively, in the form of radiation, hormone therapy or chemotherapy. In general, men at our institution receive salvage hormonal therapy only when demonstrable metastatic lesions are identified, not biochemical recurrence. Therefore, the low secondary treatment rate suggests that men with SVI can expect favorable, long-term CSS with relatively low rates of adjuvant and salvage therapy.

Despite the known risk of recurrence, there is no consensus regarding the role of adjuvant and salvage radiation therapy in these men. Traditionally, men with SVI respond poorly to ART.20,21 However, the Southwest Oncology Group 8794 trial demonstrated metastasis-free and overall survival benefits in all men with pT3 disease treated with immediate adjuvant radiation therapy.19 Conversely, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 2291122 and the phase III ARO96-09/AUO09-9523 trials failed to demonstrate a survival benefit in men with pT3b disease treated with ART. Nonetheless, several groups have noted an improvement in the biochemical recurrence rate, in the range of 10% to 38%, in men with SVI treated with salvage radiation therapy.24–28 Due to restraints in the timing and duration of treatments, conclusions regarding ART and additional treatments from our analysis should be viewed with prudence.

In addition to the lack of time dependent salvage treatment information, there are a number of other important limitations inherent to the retrospective nature of this study. Importantly, preoperative selection bias, modifications in surgical technique and changes in prostate cancer grading over the eras certainly influenced the capture and interpretation of these data. Importantly, since minimally invasive approaches to RP are associated with higher SM rates,29,30 the use of laparoscopic and robot assisted surgery in the contemporary PSA era could have influenced outcomes in these patients. A significant omission from this analysis is the route of SVI. While some studies show that the SVI route carries important information regarding biochemical recurrence, it is currently believed that the SVI route is not prognostic in patients lacking LN metastasis.9,10,18 Therefore, it was justifiably omitted from our analysis. It is also established that the finding of SVI can vary among institutions and pathologists.17 Analysis of all RP specimens at our institution is completed by an experience genitourinary patholo-gist in a uniform manner.8

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a decrease in the frequency of pT3b disease, and lower positive SMs and LN positive rates in the contemporary PSA era, SV invasion portends a poor prognosis in regard to BFS following RP. Advanced clinical stage, intermediate or high risk Gleason sum at pathological evaluation and positive SMs predicted biochemical recurrence. However, in the contemporary era, with little use of ART, men with pT3b disease have favorable 10-year CSS.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health SPORE Grant P50CA58236.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ART

adjuvant radiation treatment

- BFS

biochemical recurrence-free survival

- CSS

prostate cancer specific survival

- LN

lymph node

- MFS

metastasis-free survival

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- SM

surgical margin

- SV

seminal vesicle

- SVI

seminal vesicle invasion

Footnotes

Study received institutional review board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salomon L, Anastasiadis AG, Johnson CW, et al. Seminal vesicle involvement after radical prostatectomy: predicting risk factors for progression. Urology. 2003;62:304. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Iocca A, et al. Use of Gleason score, prostate specific antigen, seminal vesicle and margin status to predict biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001;165:119. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggener SE, Roehl KA, Smith ND, et al. Contemporary survival results and the role of radiation therapy in patients with node negative seminal vesicle invasion following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1150. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155158.79489.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billis A, Teixeira DA, Stelini RF, et al. Seminal vesicle invasion in radical prostatectomies: which is the most common route of invasion? Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39:1097. doi: 10.1007/s11255-007-9189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter SR, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Seminal vesicle invasion by prostate cancer: prognostic significance and therapeutic implications. Rev Urol. 2000;2:190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom KD, Richie JP, Schultz D, et al. Invasion of seminal vesicles by adenocarcinoma of the prostate: PSA outcome determined by preoperative and postoperative factors. Urology. 2004;63:333. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secin FP, Bianco FJ, Jr, Vickers AJ, et al. Cancer-specific survival and predictors of prostate-specific antigen recurrence and survival in patients with seminal vesicle invasion after radical pros-tatectomy. Cancer. 2006;106:2369. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein JI. Radical prostatectomy: processing, staging, and prognosis. Parts I and II. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:1185. doi: 10.1177/1066896910370473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohori M, Scardino PT, Lapin SL, et al. The mechanisms and prognostic significance of seminal vesicle involvement by prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1252. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villers AA, McNeal JE, Redwine EA, et al. Pathogenesis and biological significance of seminal vesicle invasion in prostatic adenocarcinoma. J Urol. 1990;143:1183. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partin AW, Yoo J, Carter HB, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen, clinical stage and Gleason score to predict pathological stage in men with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1993;150:110. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han M, Partin AW, Piantadosi S, et al. Era specific biochemical recurrence-free survival following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith EB, Frierson HF, Jr, Mills SE, et al. Gleason scores of prostate biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens over the past 10 years: is there evidence for systematic upgrading? Cancer. 2002;94:2282. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jhaveri FM, Klein EA, Kupelian PA, et al. Declining rates of extracapsular extension after radical prostatectomy: evidence for continued stage migration. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tefilli MV, Gheiler EL, Tiguert R, et al. Prognostic indicators in patients with seminal vesicle involvement following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;160:802. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein JI, Partin AW, Potter SR, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate invading the seminal vesicle: prognostic stratification based on pathologic parameters. Urology. 2000;56:283. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathological T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2009;181:956. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalapurakal JA, Huang CF, Neriamparampil MM, et al. Biochemical disease-free survival following adjuvant and salvage irradiation after radical prostatectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1047. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor N, Kelly JF, Kuban DA, et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:755. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Kwast TH, Bolla M, Van Poppel H, et al. Identification of patients with prostate cancer who benefit from immediate postoperative radio-therapy: EORTC 22911. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiegel T, Bottke D, Steiner U, et al. Phase III postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy compared with radical prostatectomy alone in pT3 prostate cancer with postoperative undetectable prostate-specific antigen: ARO 96-02/AUO AP 09/95. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chawla AK, Thakral HK, Zietman AL, et al. Salvage radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate adenocarcinoma: analysis of efficacy and prognostic factors. Urology. 2002;59:726. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liauw SL, Webster WS, Pistenmaa DA, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for biochemical failure of radical prostatectomy: a single-institution experience. Urology. 2003;61:1204. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosbacher MR, Schiff PB, Otoole KM, et al. Postprostatectomy salvage radiation therapy for prostate cancer: impact of pathological and biochemical variables and prostate fossa biopsy. Cancer J. 2002;8:242. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephenson AJ, Shariat SF, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2004;291:1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trock BJ, Han M, Freedland SJ, et al. Prostate cancer-specific survival following salvage radio-therapy vs observation in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2008;299:2760. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loeb S, Epstein JI, Ross AE, et al. Benign prostate glands at the bladder neck margin in robotic vs open radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2010;105:1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams SB, Chen MH, D'Amico AV, et al. Radical retropubic prostatectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: likelihood of positive surgical margin(s). Urology. 2010;76:1097. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]