Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) can be found in several tissues of mesodermal origin. Uterine tissue contains stem cells and can regenerate during each menstrual cycle with robust new tissue formation. Stem cells may play a role in this regenerative potential. Here, we report that transplantation of cells isolated from murine uterine tissue can rescue lethally irradiated mice and reconstitute the major hematopoietic lineages. Donor cells can be detected in the blood and hematopoietic tissues such as spleen and bone marrow (BM) of recipient mice. Uterine tissue contains a significant percentage of cells that are Sca-1+, Thy 1.2+, or CD45+ cells, and uterine cells (UCs) were able to give rise to hematopoietic colonies in methylcellulose. Using secondary reconstitution, a key test for hematopoietic potential, we found that the UCs exhibited HSC-like reconstitution of BM and formation of splenic nodules. In a sensitive assay for cell fusion, we used a mixture of cells from Cre and loxP mice for reconstitution and demonstrated that hematopoietic reconstitution by UCs is not a function of fusion with donor BM cells. We also showed that the hematopoietic potential of the uterine tissue was not a result of BM stem cells residing in the uterine tissue. In conclusion, our data provide novel evidence that cells isolated from mesodermal tissues such as the uterus can engraft into the hematopoietic system of irradiated recipients and give rise to multiple hematopoietic lineages. Thus, uterine tissue could be considered an important source of stem cells able to support hematopoiesis.

Introduction

The adult mammalian uterine endometrium regenerates during each menstrual cycle with robust new tissue formation. The regenerative nature of the uterus suggests that stem cells may play an important role in this tissue. Initially, it was suggested that three different kinds of epithelial stem cells—one type sensitive to estrogen, one to progesterone, and the third to both—were responsible for the regenerative ability of uterine tissue [1]. Later, Schwab and Gargett reported identification of two subsets of uterine stem/progenitor cells derived from the endometrium that had clonogenic potential for either epithelial or mesenchymal differentiation [2,3]. We have recently found that the uterus retains resident hemangioblasts from which two derivative cell clusters commit to either a hematopoietic or an endothelial lineage [4].

The stem cells that give rise to blood cells are called hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Mouse HSCs were first identified on the basis of their ability to form colonies in the spleens of lethally irradiated mice after bone marrow (BM) transfer [5,6]. A widely accepted assay used to judge whether a particular cell type has the capacity to function as an HSC is their ability to reconstitute blood cell lineages after transplantation into lethally irradiated recipients [7]. If the transplanted mice recover from BM reconstitution and all types of blood cells reappear (bearing a genetic marker from the donor animal), the transplanted cells are believed to have included stem cells.

Besides the typical BM source of HSCs, recent papers report that cells from adult non-hematopoietic tissues can contribute to the regeneration of the hematopoietic system in lethally irradiated mice [8–10]. For instance, Jackson et al. [9] describe significant hematopoietic engraftment and differentiation potential of adult skeletal muscle cells and Bjornson et al. [8] showed that neural stem cells also had HSC-like capacity. BM-derived cells also have the capacity to differentiate into other kinds of cells, including muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and hepatocytes [11–13]. In sum, this suggests that tissue-specific stem cells have differentiation potential outside of their tissue of origin. This led us to investigate in the current study whether cells derived from uterine tissue could rescue lethally irradiated mice by generating and/or supporting the major hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Here, we show that the murine uterus contains a population of stem cells that are capable of hematopoiesis.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University Health Network Animal Care Committee. We used female C57BL/6 mice and C57BL/6-TgN (ACTb-EGFP) 1Osb mice (Jackson Laboratory), nude mice (National Institutes of Health), Blimp-Cre mice, and Z/EG loxP reporter mice (expressing EGFP on Cre-mediated excision at loxP sites; generated by Novak et al. [14]).

Cell preparation

Under anesthesia, GFP+ mice were heparinized and then perfused through the descending aorta to flush all blood cells from the organs. Uterine cells (UCs) were obtained by mincing the uterus and incubating the tissue twice for 1 h with Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium, 0.25% trypsin, 2 mg/mL collagenase, and 0.01% DNAase at 37°C. Cells were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer, centrifuged, washed, counted, and suspended in a solution of 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in preparation for reconstitution. BM cells were prepared in 0.1% BSA with PBS [15]. For kidney cell preparation, kidneys were mashed and filtered to generate a single cell suspension [16]. The cells were centrifuged, washed, counted, and suspended in 0.1% BSA with PBS in preparation for reconstitution.

Flow cytometry analysis

One million UCs were stained with the following antibodies: anti-mouse Sca-1-Phycoerythrin labeled, CD34, cKit, CD45, CD31 (all BD Biosciences) and anti-mouse Thy1.2, EpCAM-Allophycocyanin labeled, CD90.1, CD44-PeCy7 labeled (all from eBioscience). Antibody incubation was carried out for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. An Alexa fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-rat antibody (Molecular Probes) was added with the unconjugated primary antibodies. Isotype-identical sera served as controls (Becton Dickinson). Cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). The fluorescence intensity of 50,000 cells for each sample was quantified.

BM reconstitution

BM cells, UCs, kidney cells (which are non-hematopoietic) [17], or a combination of either GFP+ UCs or GFP+ kidney cells with unfractionated GFP− BM cells (1:1 ratio; 3×106 cells in 250 μL/mouse) were injected into lethally irradiated female recipients (9.5 Gy γ-irradiation) through the tail vein [15]. These mice were used to assay animal survival till 30 days post-implantation and for fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry for GFP+ cells in blood, spleen, BM, lung, heart, and uterus at 8 weeks after reconstitution. In addition, at 8 weeks post-reconstitution, spleen and BM from UC+BM transplanted mice were analyzed by dual-colored flow cytometry to identify GFP+ cells that express a variety of hematopoietic lineage markers.

Long-term fate of implanted UCs

Recipient mice reconstituted with a mixture of GFP+ UCs and GFP− BM cells were housed for 12 months. GFP+ cells were quantified by flow cytometry in blood, BM, and spleen tissues. In a hematopoietic colony formation assay, GFP+ cells isolated from the chimeric recipients were cultured in MethoCult medium (StemCell Technologies 03434). Erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E), granulocyte-macrophage colony forming unit (CFU-GM), and granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, megakaryocyte colony forming unit (CFU-GEMM) progenitors were classified and quantified after 7 days in culture [18]. Recipient kidney, liver, and brain tissues were collected and perfusion fixed in 10% formalin in PBS. The fixed tissue samples were cut into 1 mm slices, embedded in paraffin wax, cut into 5 μm sections, stained with an anti-GFP antibody, and then photographed by light microscopy.

Secondary BM reconstitution

A combination of GFP+ UCs and GFP− BM cells (1:1 ratio; 3×106 cells/animal) was injected into lethally irradiated mice (primary reconstitution). After an 8-week recovery from primary BM reconstitution, BM cells (3×106 cells/animal) isolated from the chimeric recipients were injected into different irradiated wild-type recipients to establish secondary reconstitution. Nine days after secondary reconstitution, splenic tissue from the secondary recipients was examined by fluorescence microscopy for the presence of GFP+ cell colonies. In the long-term secondary reconstitution study, the percentages of cells in the blood, BM, and spleen that expressed GFP were evaluated by flow cytometry in secondary recipients 6 and 9 weeks after reconstitution.

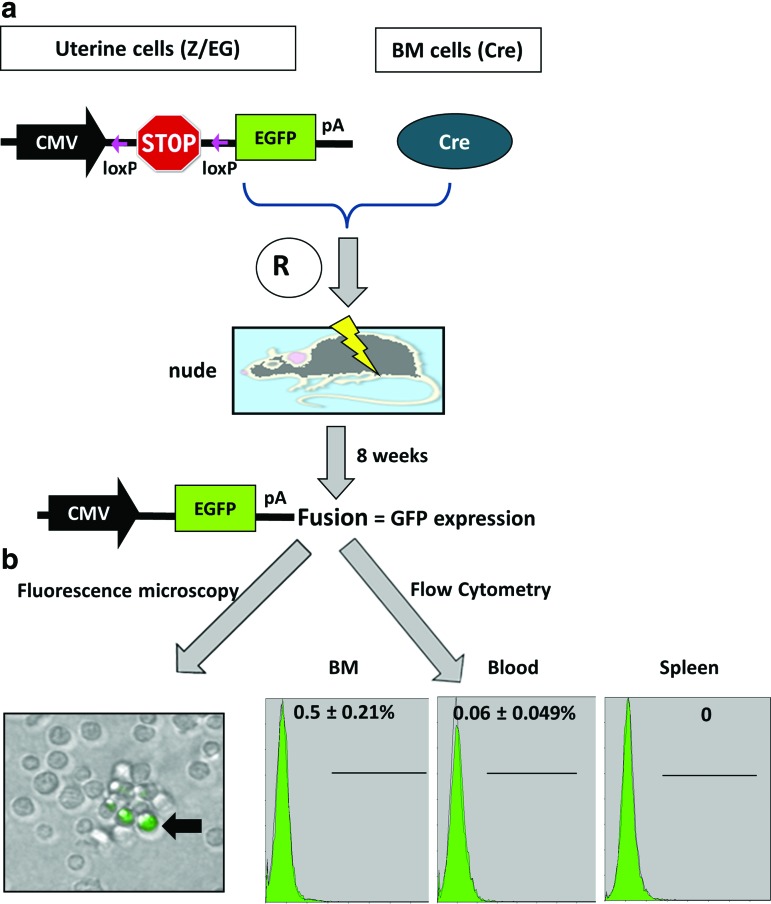

In vivo cell fusion assay using the Cre-loxP system

Using Blimp-Cre mice and the loxP-containing Z/EG reporter mouse strain, rare Cre-dependent excision events can be identified. Cre recombinase is expressed in all hematopoietic lineages and progenitors of Blimp-Cre mice [14]. When cell fusion between a Z/EG UC and a Blimp-Cre BM cell occurs, the Cre protein facilitates the deletion of a loxP-flanked transcription stop signal and turns on EGFP expression. We used these strains as a sensitive system for the contribution of UC-BM cell fusion to reconstitution by using mixed Z/EG UCs and Blimp-Cre BM cells. These cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, and then injected into irradiated nude mice to reconstitute the BM (total of 3×106 mixed cells/animal). GFP+ cells that resulted from fused Cre and Z/EG cells in the recipient BM, blood, and spleen were quantified using flow cytometry at 8 weeks after reconstitution.

BM reconstitution with uterine-resident BM stem cells

It is conceivable that BM stem cells or circulating stem cells transiently residing in donor uterine tissue could contribute to reconstitution observed in the irradiated recipients. To identify the source of the stem cells isolated from the uterus, we first irradiated and then reconstituted female C57 mice with GFP+ BM cells. In these mice, all BM-derived cells will be GFP+, including those that migrate and become resident in other tissues, such as the uterus. We assessed GFP expression in these reconstituted mice after 8 or 12 weeks in the BM, blood, and uterus by flow cytometry. Then, we performed a secondary reconstitution using a 1:1 ratio of wild-type BM and uterine-derived cells from these chimeric mice (which may contain uterine-resident GFP+ cells originating from the primary reconstituted BM) and generated a second set of chimeric mice. GFP+ cells, representing engrafted cells that were originally BM cells resident in the uterus, were quantified in the blood, BM, and spleen of the secondary recipients using flow cytometry 8 or 12 weeks after secondary reconstitution.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean±standard error. Analyses were performed using GraphPad (v. 4.0), with the critical α-level set at P<0.05. Comparisons between two groups were made using unpaired, two-tailed, non-equal variance Student's t-tests. Time course and multi-group comparisons were made using analysis of variances. When F-values were significant, differences between the groups were specified with Tukey's multiple-comparison post-tests.

Results

Identification of unique HSC-like cells in uterine tissue

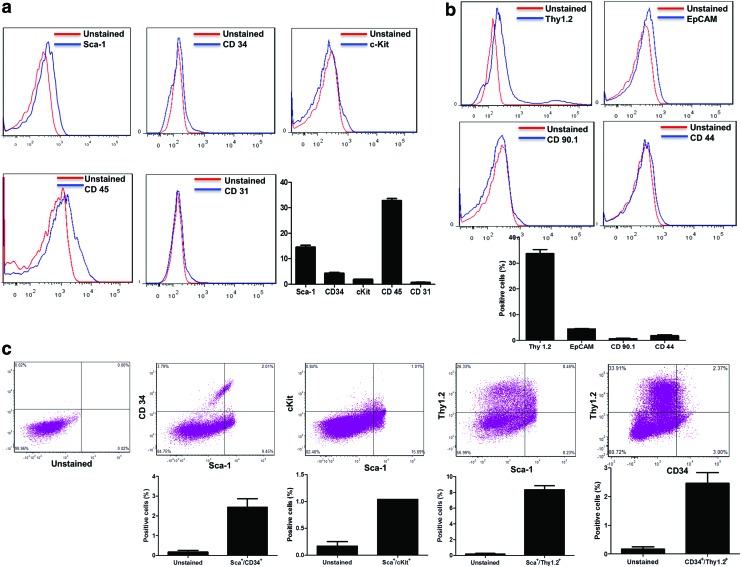

To define the nature of UCs that may be competent to produce hematopoietic cell lineages, flow cytometry was used to quantify the expression of surface antigens on cells isolated from mouse uteri. These data showed that isolated UCs are 32.86±1.5% CD45+ (which may represent the hematopoietic lineage, Fig. 1a), and 33.7±3.1% positive for Thy1.2 (which may represent the mesenchymal lineage, Fig. 1b). In the uterine hematopoietic-like compartment, 14.54±2.3% of cells are Sca-1+ (Fig. 1a). These UCs were Thy1.2hi and epithelial cell adhesion marker (EpCAM)lo (Fig. 1b), suggesting they are likely from the endometrial stroma. In summary, the UCs are Sca-1+, CD34lo, CD45hi, cKitlo, and CD31− (suggesting they are hematopoietic in lineage, Fig. 1c) but are mostly negative for uterine mesenchymal markers such as CD44, CD90.1 (Fig. 1b). These data suggest the existence of unique uterine HSC-like cells (Sca-1+, CD34lo, and c-Kitlo), which are most likely derived from the endometrial stroma.

FIG. 1.

Antigenic profiles of the isolated mouse uterine cells (UCs). (a) Representative images of flow cytometry histogram plots show the population of UCs expressing the hematopoietic cell lineage markers Sca-1, CD34, c-Kit, and CD45, and the endothelial marker CD31. The percentage of UCs expressing the lineage markers are shown in the accompanying bar graph. (b) Representative images of flow cytometry histogram plots show the population of UCs expressing mesenchymal cell lineage markers Thy1.2, EpCAM, CD90.1, and CD44. The percentage of UCs expressing mesenchymal cell lineage markers are shown in the accompanying bar graph. (c) Representative dual-colored flow cytometry plots show the CD34/Sca-1, cKit/Sca-1, Thy1.2/Sca-1, and Thy1.2/CD34 double-positive cells. Quantification of these dual-labeled cells is shown in the accompanying bar graphs. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

UCs reconstitute the hematopoietic compartment of the BM

One standard test for HSC potential is the ability for the cells to reconstitute the BM of a lethally irradiated recipient [19]. To demonstrate hematopoietic activity, the putative stem cell must produce new cells over the long term. We found that transplantation with cells from uterine preparations was capable of delaying death after myeloablation, and that all mice reconstituted with UCs alone survived significantly (P<0.01) longer over the 4 week duration of the study than those in a control group injected with kidney cells alone (Fig. 2a). Kidney cells were chosen as a negative control, because the kidney is a highly differentiated organ and renal cells lack hematopoietic activity [17]. This demonstrates that cells within the UC population have hematopoietic potential.

FIG. 2.

UCs reconstitute the hematopoietic compartment of the bone marrow (BM). (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves illustrating the percent survival (in days, y-axis) of lethally irradiated mice reconstituted with BM cells, UCs, kidney cells, or a 1:1 mixture of GFP+ UCs and wild-type BM cells. Survival was significantly greater (P<0.05) with UCs (n=10) than kidney cells (n=8) but was higher with the BM cells and highest with the mixed cells (n=20; log-rank test for trend chi-square=12.48). (b) Representative fluorescence micrographs showing GFP+ cells in recipient tissues at 8 weeks after reconstitution with UCs+BM cells. The percentage of GFP+ cells was quantified by flow cytometry. (c, d) Dual-colored flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of GFP+ cells co-expressing markers of hematopoietic lineage (double-positive cells) from recipient spleen (c) and BM (d). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

The recipient survival rate increased to 80% when mice were implanted with BM cells and 95% when mice were implanted with a 1:1 mixture of UCs freshly isolated from GFP+ transgenic mice and BM cells from wild-type mice (3×106 cells/animal, Fig. 2a), indicating a possible synergistic effect between uterine and BM cells in rescuing animals after myeloablation. After 8 weeks, 33–42% of cells in the blood, spleen, and BM of mixed UC/BM cell recipients were GFP+ (Fig. 2b), indicating the presence of implanted UCs, while GFP expression was absent in the hematopoietic tissues of mice reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of GFP+ kidney cells and wild-type BM cells (data not shown). This demonstrates that some cells isolated from the uterus are able to migrate to and engraft into the blood and major hematopoietic organs.

Fate of engrafted cells in animals rescued with UCs

Further assessment of GFP expression in the BM and spleen of the GFP+ UC/BM cell recipients (Fig. 2c, d) revealed that most GFP+ cells also expressed the hematopoietic marker CD45, as well as markers typically associated with hematopoietic progenitors or stem cell populations, including Sca-1, and, to a lesser extent, CD34 in the BM, and CD34 and AC-133 in the spleen. We also detected the expression of lymphoid (T-cell markers CD8 and CD4) and myeloid (macrophage marker Mac-3) lineages. Together, these findings suggest that the injected UCs contributed fully to hematopoietic cell lineage restoration in the recipient BM and blood.

Functional studies of potential HSCs in reconstituted mice

The studies outlined earlier demonstrate that UCs contain cells with HSC-like potential over the short term, and we next wanted to determine whether these cells could demonstrate long-term engraftment and contribute to diverse tissues. Twelve months after reconstitution, GFP expression persisted in ∼10–20% of cells in the blood, BM, and spleen of the chimeric mice (Fig. 3a). To confirm that the engrafted UCs retained their hematopoietic potential at 12 months after reconstitution, we performed a hematopoietic colony formation assay of sorted GFP+ cells from the BM of long-term reconstituted chimeric mice. GFP+ colonies were observed after 7 days in semi-solid hematopoietic growth media. Early erythroid progenitors (BFU-E), granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (CFU-GM) and multilineage progenitors (CFU-GEMM) were enumerated at frequencies of 20±4, 82±17, and 7±3 per 1×105 GFP+ BM cells, respectively (Fig. 3b). In contrast, no GFP+ colonies were detected in BM cell cultures from control mice. Supporting the widespread engraftment and multilineage potential of the implanted UCs, immunohistochemical staining further revealed GFP+ cells in parenchymal kidney, liver, and brain tissues (Fig. 3c). This suggests that stem cells derived from uterine tissue have the capacity to traffic to peripheral tissues and form differentiated cells.

FIG. 3.

UCs are capable of long-term hematopoietic reconstitution. Lethally irradiated mice were injected with a mixture of GFP+ UCs and wild-type (C57BL/6) BM cells. (a) Percentages of cells from various recipient tissues expressing GFP at 12 months after reconstitution (assayed by flow cytometry). C57BL/6, wild-type, Chimeric, UC recipients (n=5). (b) Hematopoietic colony formation assay. Sorted GFP+ cells isolated from the BM of UC recipients at 12 months post-reconstitution produced different types of hematopoietic colony-forming units (CFUs) after 7 days in differentiation culture. (c) Representative micrographs of immunohistochemical staining for GFP and endothelial marker expression in sections from recipient tissues. GFP+ UCs differentiated into kidney, liver, brain (blue arrows), and endothelial cells (red arrows) within the respective tissues. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

UCs are capable of secondary hematopoietic reconstitution

A second component of the standard test for HSC potential is long-term self-renewal, meaning stem cells isolated from a transplanted individual can themselves be used to reconstitute the BM of another, lethally irradiated recipient (secondary reconstitution). We injected BM cells from chimeric mice previously reconstituted at 8 weeks with a mixture of GFP+ UCs and wild-type BM cells into irradiated, wild-type recipients (Fig. 4a). Under fluorescence microscopy, we detected numerous GFP+ cell colonies in the splenic tissue of the secondary recipients 9 days after secondary reconstitution (Fig. 4b). GFP expression was also present in ∼20% of cells in the blood, BM, and spleen for at least 9 weeks (Fig. 4c). Altogether, these data suggest that UCs contain a population with true HSC potential, as proved by their ability to establish long-term reconstitution.

FIG. 4.

UCs are capable of secondary hematopoietic reconstitution. (a) Bone marrow cells (BMCs) isolated from UC recipients at 8 weeks after primary reconstitution were injected into a second set of lethally irradiated mice (secondary reconstitution). R, reconstitution. (b) Representative images illustrating GFP+ nodules in the secondary recipient spleen at 9 days after secondary reconstitution. (c) Percentages of cells from various secondary recipient tissues expressing GFP at 6 and 9 weeks after secondary reconstitution (assayed by flow cytometry, n=5). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Hematopoietic reconstitution by UCs is independent of cell fusion or contamination by resident BM-derived cells

Since the UCs used to reconstitute the BM of lethally irradiated mice were mixed with wild-type BM cells, we used a Cre/loxP recombination system (illustrated in Fig. 5a) to determine whether fusion of GFP+ UCs with donor BM cells could account for our observation of GFP expression in the hematopoietic compartment of reconstituted recipients. BM cells isolated from Cre mice (expressing Cre in all hematopoietic lineages and progenitors) combined with UCs isolated from Z/EG mice [14] were injected into irradiated nude mice. Since the Z/EG UCs would express GFP only when fused with Cre BM cells, these mice provided a sensitive system to visualize cell fusion events between co-injected BM and UC cells [20,21]. We detected GFP expression in <1% of recipient BM, blood, or spleen cells at 8 weeks after reconstitution (Fig. 5b), indicating that cell fusion could not account for the significant UC-derived hematopoiesis observed in the reconstituted animals.

FIG. 5.

Hematopoietic reconstitution by UCs is independent of cell fusion with BM cells. (a) Schematic illustrating the Cre/loxP recombination system used to detect cell fusion in the hematopoietic compartment of mice. Very few cells in the recipient BM expressed GFP (which indicates fusion; black arrow in photomicrograph). R, reconstitution. (b) By flow cytometry, the fusion rate (% of cells expressing GFP±standard deviation) was <1% in recipient BM, blood, and spleen at 8 weeks after reconstitution (n=3). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

BM stem cells and circulating HSCs are known to traffic transiently to or reside in uterine tissue [22,23], raising the possibility that these cells could have contributed to hematopoietic reconstitution in the irradiated recipients [24]. To address this, we first reconstituted irradiated female mice with GFP+ BM cells (Fig. 6a). Eight or twelve weeks later, GFP expression was observed in 70–75% of BM cells and in 6% of UCs (Fig. 6b, c). Next, UCs isolated from these chimeric mice (and containing a mixture of native UCs and GFP+ cells of blood or BM origin but residing in the uterus) were mixed with wild-type BM cells and used to reconstitute another group of irradiated mice. In this model, all BM-derived cells that were resident in the uterus of chimeric donor mice would express GFP, while cells of uterine origin from the chimeric donor mice would be GFP−. We detected no GFP+ cells in the BM, blood, or spleen of the secondary recipients at 8 or 12 weeks after reconstitution (Fig. 6b, c), implying that the UCs used in our initial reconstitution experiments were not likely derived from trafficking BM or circulating HSCs.

FIG. 6.

Hematopoietic reconstitution by UCs is independent of contamination by BM-derived cells. (a) Schematic illustrating the secondary reconstitution experiment to assess the possibility that BM-derived cells contributed to hematopoietic reconstitution of irradiated recipients. (b) Eight weeks after irradiated mice were injected with GFP+ BM cells (n=4), GFP+ cells were detected in recipient BM, blood, and uterine tissue by flow cytometry. By flow cytometry, GFP expression was not detected in secondary recipient tissues reconstituted with uterine tissue at 8 weeks after secondary reconstitution (n=4, reconstituted from two different primary-reconstituted mice). (c) Twelve weeks after irradiated mice were injected with GFP+ BM cells (n=4), GFP+ cells were detected in recipient BM, blood, and uterine tissue by flow cytometry. By flow cytometry, GFP expression was not detected in secondary recipient tissues reconstituted with uterine tissue at 12 weeks after secondary reconstitution (n=4, reconstituted from two different primary-reconstituted mice). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

In summary, cells isolated from the murine uterus and engrafted into the hematopoietic system of irradiated recipients gave rise to a range of blood cell types. Our data provide novel evidence of a possible HSC-like niche in the adult uterine tissue.

Discussion

The current series of experiments provides novel evidence that cells isolated from mesodermal tissues such as the uterus can engraft into the hematopoietic system of irradiated recipients and give rise to multiple hematopoietic lineages. Our data provide novel evidence of a possible HSC-like niche in the adult uterus. The prolonged regenerative capacity of the uterus that underlies the menstrual cycle led researchers many years ago to speculate that the uterus contains populations of stem cells [1]. Somewhat later, clonogenicity assays confirmed the presence of a stem cell population in uterine tissue [25,26]. Our group refined the understanding of uterine stem cells by showing that some had the properties of hemangioblasts, demonstrating the ability to differentiate along either hematopoietic or endothelial lines [4]. The stem cell potential in the uterus may play an important role in healing of tissues outside the uterus: Our group has shown that UCs home to injured myocardium and aid in functional healing [27]. Together, these results suggest that UCs may provide a convenient source of cells with hematopoietic activity. Here, we show that stem cells within the uterine tissue can successfully contribute to hematopoietic lineages in a lethally irradiated animal, suggesting they would be well suited to transplantation therapies that require cells with hematopoietic potential.

The uterus is composed of three predominant cellular compartments: endometrial epithelium, endometrial stroma (together called the endometrium), and the myometrium. Based on immunohistochemistry, all endometrial epithelia, glandular, and luminal cells expressed EpCAM [28]. Endometrial stroma is marked by Thy1.2. We examined the antigenic profile of the isolated mouse UCs by flow cytometry and found that isolated UCs are about 33% positive for CD45 (which may represent the hematopoietic lineage) and 34% positive for Thy1.2 (which may represent the mesenchymal lineage). In the hematopoietic compartment, about 15% of the cells are Sca-1+. The uterine Sca-1+ cells were Thy1.2hi and EpCAMlo, suggesting these cells are most likely from the endometrial stroma. Our data also showed that these cells are CD34lo, CD45hi, cKitlo, and CD31−, suggesting they are hematopoietic in lineage, but are mostly negative for uterine mesenchymal markers such as CD44, CD90.1. These data suggest the existence of unique uterine HSC-like cells (Sca-1+, CD34lo, and c-Kitlo), which were most likely derived from the endometrial stroma.

When transplanted alone, UCs were able to significantly extend the lifespan of lethally irradiated mice compared with those transplanted with kidney cells, suggesting that UCs can contribute to short-term hematopoietic function in these mice. Despite this hematopoietic function, UCs alone had a limited capacity for long-term reconstitution of the hematopoietic system of these mice. To assess the hematopoietic activity of cells derived from uterine tissue, we adopted a competitive BM transplantation model in which lethally irradiated mice were given a test cell population from a distinguishable strain of mice mixed with BM [29,30]. UCs were prepared from the uteri of GFP+ mice, mixed with whole BM from wild-type mice, and transplanted into lethally irradiated wild-type mice. The recipient survival rate reached 95% after this procedure. After 8 weeks, approximately 42% of cells in the blood, BM, and spleen of recipient mice were GFP+, indicating the presence of implanted UCs. Further assessment of GFP expression in the BM and spleen of the mice transplanted with GFP+ cells revealed that most GFP+ cells also expressed the hematopoietic marker CD45 and other markers typically associated with hematopoietic progenitor/stem cell populations, such as Sca-1 and CD34. These data suggest that the injected UCs contributed to hematopoietic cell lineage restoration in the recipient BM and blood.

A major principle of HSC biology is that true stem cells must be highly proliferative and able to generate progeny that can repopulate secondary recipients [31,32]. Thus, we injected BM cells from chimeric mice (previously reconstituted at 8 weeks with a mixture of GFP+ UCs and wild-type BM cells) into irradiated, wild-type recipients. We found numerous GFP+ cell colonies in the splenic tissue of the secondary recipients at 9 days after secondary reconstitution. GFP expression was detected in the blood, BM, and spleen for at least 9 weeks. Together, these findings suggest that uterine tissue contains a cell population with true HSC-like ability to establish long-term reconstitution.

Our procedure for UC transplantation did not include sorting cells for stem cells markers. The cells with HSC-like potential likely made up only a small percentage of the transplanted cells. It is possible that the transplanted UCs without stem cell potential contributed to HSC-like UC cell engraftment by the production of cytokines or extracellular matrix material. Further studies will be needed to delineate the precise stem cell and microenvironment properties required for optimal UC hematopoietic function and engraftment. Our data lead us to suggest that the uterus contains a cell population with HSC-like phenotypes and activities. However, what are the specific characteristics associated with these hematopoietically active cells in the uterus? We propose three possible models to account for their activity. First, it is possible that the adult uterus contains multiple distinct stem cell populations: a mesenchymal stem cell, an HSC, and possibly other stem cell types. Second, it is possible that stem cells resident in the murine uterus, well known to be potent stem cells [2], can transdifferentiate when placed in a challenging environment. Third, it is possible that a primitive multipotent stem cell exists in the uterus and is capable of differentiating into hematopoietic cell types. We recently reported such a cell—a non-BM-derived hemangioblast in the adult uterus [4]. Since the hematopoietic reconstitution by UCs is not a function of fusion with donor BM cells or of contamination by resident BM-derived cells in the uterine tissue, our currently favored model is that uterine hemangioblasts may account for this hematopoietic activity.

Our observations not only raise important questions about the specificity of cell fate in developmental biology but also reveal the clinical potential of using ectopic stem cells for reconstitution of hematopoiesis. Some questions remain to be answered, including confirming the anatomic location of the uterine HSC-like niche, delineating the specific immunophenotypes of the UCs with HSC-like potential, as well as the potential of epithelial and mesenchymal stem cells and determining the physiological significance of putative stem cells of various types in uterine tissue. This study demonstrated HSC-like cells in the uterus. However, we did not evaluate differences between these cells and HSCs in the BM. Future work will also examine the specific similarities and differences between BM and UCs with hematopoietic activity. In addition, these studies have not outlined the prevalence of these reconstitution-capable HSC-like cells within the uterus, a question we plan to address in future studies. It should also be noted that we did not achieve 100% GFP+ reconstitution in the BM of recipient mice in this study. We have, however, established that cells within the uterine niche are capable of performing HSC-like functions within the BM, paving the way for more mechanistic studies. These studies will include a detailed lineage-tracing or lineage-depletion examination of the contribution and differentiation capability of UCs from the reconstituted BM to the GFP+ cells found in peripheral organs, such as the kidney, liver, and brain (Fig. 3c). It is worth mentioning that some groups have identified stem/progenitor cells in menses [33,34]. Thus, suitable uterine tissue could be an easily accessible cell source that is useful for treatment of blood diseases or stem cell-based therapy. Indeed, a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial exploring the use of UCs for stem cell therapy is currently underway [35]. More extensive mechanistic evaluations, along with clinical trials, are required to determine the role these cells might play in future therapies.

Summary

We have shown that the uterus contains an HSC-like stem cell compartment that can reconstitute the BM of lethally irradiated mice. These UCs show stem cell properties in long-term and secondary reconstitution studies, suggesting these cells have true hematopoietic potential. We have excluded the possibility that these results are due to either fusion of the UCs with BM-derived cells or the function of BM cells resident in the uterus. These HSC-like UCs may provide a potent and convenient stem cell source for future HSC therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kristie Jolliffe for her assistance with the preparation and editing of this article. This research was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP86661) to R.-K.L. R.-K.L. holds a Canada Research Chair in cardiac regeneration. A.K. holds the Gloria and Seymour Epstein Chair in Cell Therapy and Transplantation, University Health Network, and the University of Toronto.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Prianishnikov VA. (1978). On the concept of stem cell and a model of functional-morphological structure of the endometrium. Contraception 18:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gargett CE. (2007). Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update 13:87–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwab KE. and Gargett CE. (2007). Co-expression of two perivascular cell markers isolates mesenchymal stem-like cells from human endometrium. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 22:2903–2911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Z, Zhang Y, Brunt KR, Wu J, Li S-H, Fazel S, Weisel RD, Keating A. and Li R-K. (2010). An adult uterine hemangioblast: evidence for extramedullary self-renewal and clonal bilineage potential. Blood 116:2932–2941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Till JE. and McCulloch EA. (1961). A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res 14:213–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu AM, Siminovitch L, Till JE. and McCulloch EA. (1968). Evidence for a relationship between mouse hemopoietic stem cells and cells forming colonies in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 59:1209–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domen J. and Weissman IL. (1999). Self-renewal, differentiation or death: regulation and manipulation of hematopoietic stem cell fate. Mol Med Today 5:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjornson CR, Rietze RL, Reynolds BA, Magli MC. and Vescovi AL. (1999). Turning brain into blood: a hematopoietic fate adopted by adult neural stem cells in vivo. Science 283:534–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson KA, Mi T. and Goodell MA. (1999). Hematopoietic potential of stem cells isolated from murine skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:14482–14486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang W. (2000). Role of muscle-derived cells in hematopoietic reconstitution of irradiated mice. Blood 95:1106–1108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari G, Cusella-De Angelis G, Coletta M, Paolucci E, Stornaiuolo A, Cossu G. and Mavilio F. (1998). Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors. Science 279:1528–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, et al. (2001). Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature 410:701–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, Mars WM, Sullivan AK, Murase N, Boggs SS, Greenberger JS. and Goff JP. (1999). Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science 284:1168–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, Nagy A. and Lobe CG. (2000). Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated excision. Genes N Y N 200028:147–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazel S, Cimini M, Chen L, Li S, Angoulvant D, Fedak P, Verma S, Weisel RD, Keating A. and Li R-K. (2006). Cardioprotective c-kit+ cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. J Clin Invest 116:1865–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dekel B, Zangi L, Shezen E, Reich-Zeliger S, Eventov-Friedman S, Katchman H, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Margalit R. and Reisner Y. (2006). Isolation and characterization of nontubular sca-1+lin- multipotent stem/progenitor cells from adult mouse kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:3300–3314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito T. (2003). Stem cells of the adult kidney: where are you from? Nephrol Dial Transplant 18:641–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bubnic SJ. and Keating A. (2002). Donor stem cells home to marrow efficiently and contribute to short- and long-term hematopoiesis after low-cell-dose unconditioned bone marrow transplantation. Exp Hematol 30:606–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulop GM. and Phillips RA. (1989). Use of scid mice to identify and quantitate lymphoid-restricted stem cells in long-term bone marrow cultures. Blood 74:1537–1544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagy A. (2000). Cre recombinase: the universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis 200026:99–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauer B. (1998). Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods 14:381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du H. and Taylor HS. (2007). Contribution of bone marrow-derived stem cells to endometrium and endometriosis. Stem Cells 25:2082–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mints M, Jansson M, Sadeghi B, Westgren M, Uzunel M, Hassan M. and Palmblad J. (2008). Endometrial endothelial cells are derived from donor stem cells in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 23:139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cogle CR. and Scott EW. (2004). The hemangioblast: cradle to clinic. Exp Hematol 32:885–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan RWS, Schwab KE. and Gargett CE. (2004). Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod 70:1738–1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwab KE, Chan RWS. and Gargett CE. (2005). Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril 84Suppl 2:1124–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xaymardan M, Sun Z, Hatta K, Tsukashita M, Konecny F, Weisel RD. and Li R-K. (2012). Uterine cells are recruited to the infarcted heart and improve cardiac outcomes in female rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52:1265–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Zillwood RM, Nguyen HPT. and Wu D. (2009). Isolation and culture of epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal stem cells from human endometrium. Biol Reprod 80:1136–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison DE. (1980). Competitive repopulation: a new assay for long-term stem cell functional capacity. Blood 55:77–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison DE, Astle CM. and Lerner C. (1988). Number and continuous proliferative pattern of transplanted primitive immunohematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:822–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA. and Till JE. (1963). The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies. J Cell Physiol 62:327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spangrude GJ, Smith L, Uchida N, Ikuta K, Heimfeld S, Friedman J. and Weissman IL. (1991). Mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 78:1395–1402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hida N, Nishiyama N, Miyoshi S, Kira S, Segawa K, Uyama T, Mori T, Miyado K, Ikegami Y, et al. (2008). Novel cardiac precursor-like cells from human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal cells. Stem Cells 26:1695–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng X, Ichim TE, Zhong J, Rogers A, Yin Z, Jackson J, Wang H, Ge W, Bogin V, et al. (2007). Endometrial regenerative cells: a novel stem cell population. J Transl Med 5:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bockeria L, Bogin V, Bockeria O, Le T, Alekyan B, Woods EJ, Brown AA, Ichim TE. and Patel AN. (2013). Endometrial regenerative cells for treatment of heart failure: a new stem cell enters the clinic. J Transl Med 11:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]