Abstract

The adherence to masculine norms has been suggested to be influenced by social settings and context. Prisons have been described as a context where survival is dependent on adhering to strict masculine norms that may undermine reintegration back into the larger society. This study attempted to examine the relationship between masculine norms, peer support, and an individual’s length of incarceration on a sample of 139 African American men taking part in a pre-release community re-entry program. Results indicate that peer support was associated with length of incarceration and the interaction between the endorsement of masculine norms and peer support significantly predicted the length of incarceration for African American men in this sample. Implications for incarcerated African American men and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords: Men, Masculinity, Incarceration, Peer Support

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010), as of 2009 there were a total of 2,284,900 adult jail and prison inmates in the United States. Men represented 82% of those incarcerated. In 2010, 708,677 incarcerated individuals were released from prison (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011). In 2010, the average yearly, per person cost associated with incarceration at the Federal level was $28,284 (UScourts.gov, 2011) and the average cost at the State level was approximately $24,000 (The Pew Center on the States, 2008). The magnitude of these numbers demonstrates the economic costs that occur as a result of imprisonment. While this provides some measure of the effect of incarceration on a federal or state economic scale, it does not reveal the impact on the family unit.

Across all racial and ethnic groups the rates of incarceration have risen dramatically in the past 30 years, with the highest increases occurring among African American men. According to Harrison and Karberg (2004), African American men make up approximately 45% of the United States prison population and are incarcerated at a rate that is eight times more than White men. Discretionary decision-making policies have lead to African American men being arrested, charged, and convicted at rates much higher than their White counterparts (Pewewardy & Severson, 2003). The impact of greater criminal justice involvement, including longer prison sentences, increases one’s susceptibility to the health and social risks and threats associated with incarceration. The disparities in incarceration rates also amplify and perpetuate the problems faced by African American men, their families and their community.

The disproportionate number of incarcerated African American men makes it important to examine the effects of prison on their individual, family, and community functioning. From an individual perspective, research indicates that males in prison are one and a half times more likely than females in prison to die from AIDS. Incarcerated African Americans are two and a half times more likely than incarcerated Whites or Hispanics to die from AIDS-related complications (Maruschak, 2006). Prison is also associated with more communicable disease, increased risk of sexually transmitted disease and overall poor health outcomes (London & Myers, 2006; Thomas & Torrone, 2006). Several studies indicate that African American men face increased barriers to employment on release (Cooke 2005; Marbley & Ferguson, 2005; McKinnon & Humes, 2000). These barriers have been discussed as a manifestation of institutionalized racism. Furthermore, African American men released from prison have identified difficulties securing stable living arrangements after incarceration, which negatively affects their ability to operate in society (Cooke, 2005). This inability to secure housing and difficulties finding employment significantly contribute to high rates of re- imprisonment among African American men (Marbley & Ferguson, 2005).

The health, employment and housing issues described above extend beyond problems faced by individuals and have implications for family and community life. Prison can interfere with African American men’s family and other social networks and can diminish social cohesion (Thomas & Torrone, 2006). It can also lead to negative community health effects, such as increased transmission of sexually transmitted diseases by formally incarcerated men (Thomas & Torrone, 2006). London and Myers (2006) indicated that due to the disproportionate number of incarcerated African American men, it is likely that, without intervention, poorer life course and health trajectories will continue for their families as well as their communities. Recognizing that all men, and specifically African American men, engage in behaviors that lead to higher rates of imprisonment than women, consideration of their gendered experiences is critical for improving life outcomes among this population.

Masculinity and Men’s Functioning

According to Connell (2000), masculinity has multiple adaptations and is arranged in a complex manner along the lines of dominance and subordination. Hegemonic masculinity can be understood as a set of practices that support the dominance of men over women and other “lesser masculinities” (e.g., gay men and men of color; Connell, 1995). While the initial conceptualization of masculinity was that of a static structure only accessible to some (i.e., White men), the current conceptualization has changed. There is recognition that different masculine norms exist and they are contextually dependent, changeable and dynamic (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005).

Research indicates that context plays an important role in an individual’s masculine identity (Connell, 1995; Demetriou, 2001; Lusher & Robins, 2010). Within the prison context, features of masculinity such as dominance, power, and control are often on display (Seymour, 2003). Evans and Wallace (2008) reported inmates who are characterized by the masculine norms of violence and dominance are seen to be the aggressors within the prison system, while those not exhibiting such traits are often victimized. Within the prison setting, men may find it advantageous to adopt and amplify certain masculine traits while minimizing others. Research on this topic has documented that becoming a perpetrator and increasing one’s association with the masculine norm of violence may be the only way to achieve safety from being victimized in prison (Evans & Wallace, 2008). In this regard, men may rely heavily on violence in prison to demonstrate their masculinity (Connell, 2000). The adoption of traditional masculine norms are not only associated with negative outcomes. Adherence to certain masculine norms in the prison setting may facilitate meeting the demands of the prison context (Mahalik, Locke et al., 2003).

Not all prisoners adopt masculine norms within the prison setting. Some research points out that while barriers do exist toward men seeking treatment services in prison, there are a number of problems for which inmates are likely to seek services (Morgan, Steffan, Shaw & Wilson, 2007). Indeed, there is evidence that male inmates experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety may have an increased likelihood of requesting services (Diamond, Magaletta, Harzke & Baxter, 2008).

While adherence to masculine norms such as violence and dominance may play a functional role within the prison environment, they may have the opposite effect as one reintegrates back into family, community and social life (Mahalik, Locke et al., 2003). Within intimate partner violence research, the endorsement of the masculine roles of violence and power are seen as being used to control women (Prospero, 2008). Additionally, the masculine norms of power and dominance have been associated with sexual aggression (Locke & Mahalik, 2005). There is also some evidence that men conforming to more traditional masculine norms view help-seeking as stigmatizing (McKelly & Rochlen, 2010). These norms may also be associated with men’s successful reentry from prison back into family and community life (McKelly & Rochlen, 2010).

Men’s transition from prison into the community may require reliance on others, something negatively reinforced in the prison context and potentially stigmatizing for men who conform to traditional masculine norms. These masculine norms may be negatively associated with social support, an area identified with positive physical and mental health and lowered recidivism rates (Iwamoto, Gordon, and Oliveros, 2012; La Vigne, Visher, & Castro, 2004; Shinkfield & Graffam, 2009). Reintegration to family and community life may be predicated on men’s perceptions of the levels and equality of supports available to them as they make this transition.

Peer Support and Men’s Functioning

Among incarcerated men, both real and perceived supports have important implications for functioning. Studies indicate that individuals with few family supports are particularly at risk for recidivism and that social support is extremely important to their community reintegration (La Vigne et al., 2004; Shinkfield & Graffam, 2009). Fewer supports present as a risk factor, while more are viewed as protective. Peer support is seen as protective because it has been demonstrated to shield individuals from engaging in criminal activities as well as aid their reentry and rehabilitation after release from prison (Cullen, 1994). Research has also shown that increases in support may serve to decrease criminal involvement as well as mediate and moderate additional negative outcomes, such as psychological problems (Hochstetler, DeLisi, & Pratt, 2008; Iwamoto et al., 2012). Perceptions of peer support have also been demonstrated to reduce or mediate negative psychological effects that may be encountered while living in a hostile environment, such as prison (Iwamoto et al., 2012; Johnson, Listwan, Colvin, Hanley, & Flannery, 2010). These findings indicate that increases in peer support, both real and perceived, may act to insulate individuals from a number of negative corollaries while imprisoned, as well as assist with reintegration and lessen the likelihood of recidivism on release.

Existing evidence suggests that men experience greater pressure to endorse and adhere to dominant masculine norms. These norms are associated with negative health and behavioral consequences and context impacts which norms are valued and endorsed. This study used a convenience sample of incarcerated African American men to: 1) Examine the relationship between the endorsement of masculine norms and an individuals’ length of incarceration; 2) Examine the relationship between a measure of peer support and length of incarceration; 3) Examine the interaction between masculine norms and peer support as related to length of incarceration. We hypothesized that increased endorsement of masculine norms would be positively associated with length of incarceration and increased levels of peer support would be negatively associated with an individual’s incarceration length. We also hypothesized the interaction of lower levels of endorsed masculine norms and higher levels of endorsed peer support would be associated decreased length of incarceration.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were 139 African American men taking part in a pre-release community re-entry program. Men who were invited to participate in the intervention and study were over the age of 18, able to give consent, and within 3–6 months of release from incarceration. The mean age of the sample was 30.2 (SD = 7.95) with an average length of incarceration of 17.83 months (SD = 17.06). The mean for the CMNI-22 was 54.46 (SD = 4.89), indicating the sample was high in their conformity to masculine norms. The mean in the current study was comparatively higher than the mean of the sample in Rochlen, McKelley, Suizzo and Scaringi (2008) study which found a mean of 26.58 (SD = 5.28) for men caring for their children full time. The average total score for the Peer Support measure was 40.96 (SD = 8.25) which is somewhat higher than the mean of 36.7 found in a national sample (Institute of Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University, 2011).

Measures

Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI-22; Mahalik, Locke et al., 2003)

The CMNI-22 is a revised and shortened version of the original CMNI developed by Mahalik, Good, and Englar-Calrson (2003). The purpose of the CMNI-22 is to evaluate the degree to which individuals conform to the 11 separate masculine norms identified during the development of the original CMNI. The measures items are rated on a 4-point scale (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree) that seeks to identify the norms of dominant masculinity. These include risk-taking, disdain for homosexuality, violence, winning, emotional control, power over women, dominance, playboy, self-reliance, primacy of work, and pursuit of status. The measure includes items such as “Sometimes violent action is necessary” and “I love it when men are in charge of women.” The CNMI-22 was developed by using only the two highest loading items on each of the 11 subscales of the CMNI-94. Mahalik, Locke et al. (2003) reported the CMNI-22 total score correlates .92 with the original CMNI total score. The CMNI achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of .66 in the current study. This is comparable to the internal consistency of .65 and .64 reported for the measure in samples examining full time fathers and working adult males (Rochlen et al., 2008).

Texas Christian University Adult Family and Friends Assessment - Peer Scales

In the current study, peer support was examined through the use of the eleven items that comprise the Peer Scales of the Texas Christian University Adult Family and Friends Assessment (Joe, Simpson, Greener, & Rowan-Szal, 2004). The Adult Family and Friends Assessment and specifically the peer scales address conflict and warmth in one’s relationships with peers as well as focus on mutual activities and levels of involvement (Institute of Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University). These items are scored on a 0–5 likert type scale (e.g., 0 = never and 5 = always), with lower scores demonstrating less perceived peer social support. The measure includes items such as “Spent Time with their Families” and “Worked Regularly on a Job.” Some items, such as “Spent Time with a Gang” and “Got Arrested/had Legal Problems” were reverse coded. The reported reliability estimate for the Peer Scales in the developmental sample was alpha = .94 (Institute of Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University) and in this study was alpha = .89.

Procedures

This study was part of a larger community re-entry evaluation project. The goal of this re-entry initiative was to reduce recidivism rates for men reintegrating into the community from prison. The men in this study were located within one of two minimum-security correctional facilities in the state of Connecticut. These particular facilities provide programs specific to education and addiction, with a focus on successful community reintegration. Factors associated with successful community reintegration as well as a reduction in re-offending are the primary focus of the re-entry project. Participants were informed that the project received a Certificate of Confidentiality from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and, therefore, their information would be protected from release under subpoena. Additionally, all participants were informed that the information they provided would be anonymous and in no way affect their parole, probation, or release status. Participants were also made aware that their participation in the project was voluntary and they would be allowed to withdraw at any point. The data for this project was collected by trained research assistants during semi-structured interviews that ranged in length from 45 minutes to two hours. Information regarding an individual’s current length of incarceration was gathered as part of the interview process. This information was obtained through self-reporting as part of the interview and was coded as number of months for current incarceration.

Results

Correlation Analysis

The first analysis examined our first hypothesis, regarding the relationship between the endorsement of masculine norms and an individuals’ length of incarceration. This hypothesis was not supported as the CMNI total score did not significantly correlate with length of incarceration, (r (135) = .15, p = .08). Next we examined our second hypothesis, that there was a relationship between an individual’s peer support and length of incarceration. This hypothesis was supported as the Peer Support total score significantly correlated with length of incarceration, (r (137) = −.22, p < .05). It was suspected that age might explain this relationship. However, after controlling for age, Peer Support still significantly correlated with length of incarceration, (r (134) = −.21, p < .05). These results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of Correlation Analysis

| CMNI Total Score |

Peer Support Total Score |

Age | Length of Incarceration |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMNI Total Score | −.207* | −.250** | .150 | |

| Peer Support Total Score | −.207* | .266** | −.218* |

p < .05

p < .01

n = 137

Regression Analysis

This analysis used simultaneous multiple regression to examine our third hypothesis, that the interaction between masculine norms and peer support would be related to length of incarceration (see Table 2). This table provides the information for each step in the equation as well as the standardized beta coefficients and significance value for each predictor. We hypothesized that the interaction of lower levels of endorsed masculine norms and higher levels of endorsed peer support would predict decreased length of incarceration. In order to conduct this analysis, both total scores were centered in order to reduce the chance of multicollinearity between the predictors and the interaction term (Aiken & West, 1991). The interaction term was created by multiplying the centered CMNI and Peer Support total scores. In the first step, the centered variables were entered as independent variables in the analysis. In the second step, the centered variables as well as the interaction term were entered as independent variables.

Table 2.

Results of Main Effects and Interaction Effects

| Predictors | Beta | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: F(2, 134) = 3.96, p < .05; R2 = .06 | ||

| CMNI | .112 | .196 |

| Peer Support | −.186 | .032 |

| Step 2: F(3, 133) = 4.59, p < .001; R2 = .09 | ||

| CMNI | .093 | .274 |

| Peer Support | −.174 | .041 |

| CMNI × Peer Support | −.196 | .020 |

n = 137

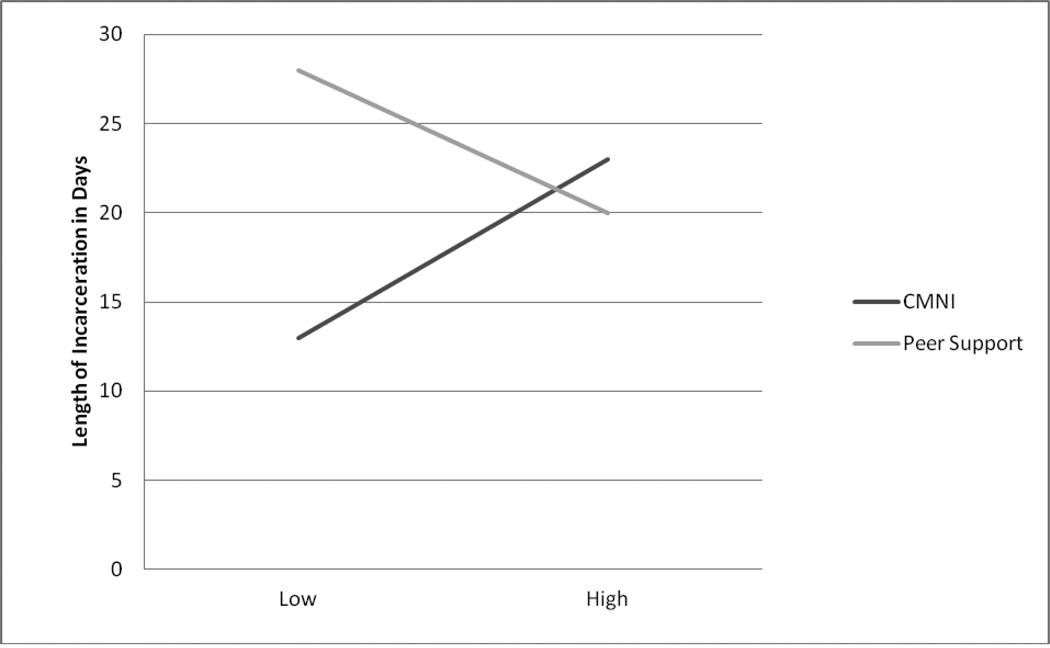

The first step was significant, F (2, 134) = 3.96, p < .05; R2 = .06. These results indicated that increased Peer Support scores significantly predicted decreased length of incarceration, however the CMNI failed to significantly predict this outcome. In the second step Peer Support, the CMNI and the interaction of Peer Support and the CMNI were examined. The second step was also significant, F (3, 133) = 4.59, p < .001; R2 = .09 (see Figure 1). In this analysis Peer Support and the interaction between Peer Support and the CMNI were related to decreased length of incarceration. This model explained a significant portion of the variance (9%).

Figure 1.

Peer Support and CMNI Interaction

p < .01

Discussion

The impact of incarceration has far-reaching consequences for men’s functioning, including their mental and physical health as well as reintegration into the community (Cooke, 2005; Iwamoto, et al, 2012; Tripp, 2009; Williams, 2007). The importance of identifying factors that influence men’s functioning while in prison and upon release has a number of implications for these men, their families, and communities. Recognizing that masculine norms may lead to negative incarceration outcomes can aid in circumventing or treating potential consequences, such as homelessness, strained family relations, and public health concerns (Bonhomme, Stephens, & Braithwaite, 2006). These issues become all the more relevant in the African American population, where disparities related to imprisonment are prevalent (London & Myers, 2006).

Prior research has demonstrated that masculine norms are prevalent within prison settings (Evans & Wallace, 2008; Lutze & Murphy, 1999). We sought to expand this line of questioning by examining one’s endorsement of masculine norms and length of incarceration. This question grew out of previous research showing a link between masculinity, violence and prison (Connell, 2000; Evans & Wallace, 2008). We therefore hypothesized that the endorsement of masculine norms would be associated with longer incarceration time. The results demonstrated that the endorsement of masculine norms approached significance as a predictor of increased incarceration length. Perhaps with a larger sample size this correlation would have been significant. While the current study examined the relationship of the CMNI total score with length of incarceration, the CMNI also contains 11 subscales. Future research may benefit from examining the relationship between specific subscales and outcomes of interest, such as an individual’s length of incarceration.

We also examined the relationship between peer support and length of incarceration. Our results indicated that peer support and length of incarceration were significantly associated. Peer support can be a protective factor during community reintegration, (Hochstetler et al., 2008; Iwamoto et al., 2012). This finding underscores the need to increase men’s reliance on positive peer support upon release. Specifically, this finding highlights the need to develop interventions that increase men’s likelihood of using pro-social support during community reintegration, rather than relying on supports with associated negative outcomes, such as gang involvement.

An examination of a potential interaction between masculine norms and peer support as related to an individual’s length of incarceration was also examined. These results indicated that less endorsement of masculine norms and higher endorsement of peer support predicted a decreased length of incarceration for individuals in this study.

The findings from these analyses have several implications. While some research indicates that adopting masculine norms within the prison setting may serve a functional role, there is also research suggesting that adherence to masculine norms is associated with negative outcomes (Mahalik, Locke et al., 2003; Locke & Mahalik, 2005). Although endorsement of masculine norms in this sample was not significantly associated with one’s length of incarceration, there was a significant interaction with peer support that predicted an increased length of incarceration.

Understanding how incarcerated African American men express masculinity, how these traditional masculine norms interact with other important areas of functioning such as one’s support system, and the relationship to outcomes associated with successful reentry are important areas of inquiry. Additionally, these results provide evidence of the positive benefits of peer support for incarcerated African American men. This demonstrates the importance of maintaining and increasing positive social networks for African American men during incarceration and when reintegrating into the community. Length of incarceration is only one of many important outcomes related to the experience of incarcerated African American men. This study will hopefully steer future research to examine the role of masculinity and support systems and their relation with prison involvement and community reintegration. This raises important questions about the direction of the causal relationship between length of incarceration and the presence or consistency of extended social networks. More studies that examine the relationship between social networks and length of incarceration with an eye toward either intervention or prevention for incarcerated men and their social networks are recommended.

This study begins to examine how masculinity is understood within the prison context for African American men, results should be considered taking into account study limitations. This study was cross sectional, and causality cannot be inferred. The results may not be generalizable to other populations. These findings highlight the difficulty of conducting research with this often invisible and understudied population and replicating the results. They also underscore the difficulty of measuring masculinity in a situation where the context may fundamentally alter how an individual expresses it.

While the current study has several limitations, it adds to our knowledge of the complexities involved in understanding the endorsement of masculine norms in diverse settings with understudied populations. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine the role of masculine norms and peer-support with incarcerated African American men and its affect on incarceration length. These findings and their importance to future research are significant given the incarceration and health disparities faced by African American men. Finally, these results indicate that, as masculinity continues to be examined in regards to this population, its relationship with other outcomes such as health-related issues, employment after release and recidivism should be considered.

Contributor Information

Derrick M. Gordon, Yale University School of Medicine

Samuel W. Hawes, Yale University School of Medicine

M. Arturo Perez-Cabello, Yale University School of Medicine.

Tamika Brabham-Hollis, Yale University School of Medicine.

A. Stephen Lanza, Family Reentry.

William J. Dyson, Central Connecticut State University

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme J, Stephens T, Braithwaite R. African-American males in the United States prison system: Impact on family and community. Journal of Men's Health & Gender. 2006;3:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Correctional populations in the United States, 2009. [Retrieved on August 22, 2011];2010 from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus09.pdf.

- Bureau of Justice StatisticsCorrectional populations in the United States, 2010 2011Retrieved on April 20th, 2012from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus09.pdf

- Brannon R, Juni S. A scale for measuring attitudes towards masculinity. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1984;14:6. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. St. Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. The Men and the Boys. Allen & Unwin: NSW; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19:829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke CL. Going home: Formerly incarcerated African American men return to families and communities. Journal of Family Nursing. 2005;11:388–404. doi: 10.1177/1074840705281753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen FT. Social support as an organizing concept for criminology: Presidential address to the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Justice Quarterly. 1994;11:527–560. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou DZ. Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique. Theory and Society. 2001;30:337–361. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond PM, Magaletta PR, Harzke AJ, Baxter J. Who requests psychological services upon admission to prison? Psychological Services. 2008;5:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR, Ward CH. Masculine gender-role stress: Predictor of anger, anxiety, and health-risk behaviors. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:133–141. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T, Wallace P. A Prison within a prison?: The masculinity narratives of male prisoners. Men and Masculinities. 2008;10:484–507. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston C. Prisoners and their families: Parenting issues during incarceration. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, Karberg JC. Prison and jail inmates at midyear in 2003 (NCJ Publication No. 203947) Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. 2004:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstetler A, DeLisi M, Pratt TC. Social support and feelings of hostility among released inmates. Crime & Delinquency. 2010;56:588–607. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University. Adult Family and Friends Assessment. [Retrieved on January 25, 2012];2011 from: 1/25/ http://www.ibr.tcu.edu/pubs/datacoll/ADCforms.html#ClientFunctioningTrtEngagement. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Gordon D, Oliveros A. The role of masculine norms, informal support on depression and anxiety among incarcerated men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0025522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, Greener JM, Rowan-Szal GA. Development and Validation of a Client Problems Profile and Index for Drug Treatment. Psychological Reports. 2004;95:215–234. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.1.215-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Listwan S, Colvin M, Hanley D, Flannery D. Victimization, social support, and psychological well-being: A study of recently released prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2010;37:1140–1159. [Google Scholar]

- La Vigne NG, Visher C, Castro J. Chicago prisoners’ experiences returning home. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; 2004. [Retrieved August 22, 2011]. from http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=311115. [Google Scholar]

- Locke BD, Mahalik JR. Examining masculinity norms, problem drinking, and athletic involvement as predictors of sexual aggression in college men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:279–283. [Google Scholar]

- London AS, Myers NA. Race, incarceration, and health: A life-course approach. Research on Aging. 2006;28:409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lusher D, Robins G. A social network analysis of hegemonic and other masculinities. The Journal of Men's Studies. 2010;18:22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lutze FE, Murphy DW. Ultramasculine prison environments and inmates’ adjustment: It’s time to move beyond the"Boys Will Be Boys” paradigm. Justice Quarterly. 1999;16:709–733. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Good GE, Englar-Carlson M. Masculinity scripts, presenting concerns, and help seeking: Implications for practice and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RP, Gottfried M, Freitas G. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2003;4:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Marbley AF, Feruguson R. Responding to prisoner reentry, recidivism, and incarceration of inmates of color: A call to the communities. Journal of Black Studies. 2005;35:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L. HIV in prisons, 2004 (Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, NCJ 213897) [Retrieved September 3, 2011];2006 from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp04.pdf.

- McKelly RA, Rochlen AB. Conformity to masculine norms and preferences for therapy or executive coaching. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2010;11:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon J, Humes K. The Black population in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RD, Steffan JS, Shaw L, Wilson S. Needs for and barriers to correctional mental health services: Inmate perceptions. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1181–1186. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. Assessing the factor structures of the 55- and 22-item versions of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2011;5:118–128. doi: 10.1177/1557988310363817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, Moradi B. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory and development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory-46. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2009;10:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Center on the States. One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008. [Retrieved August 22, 2011];Public Safety Performance Project. 2008 from http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/sentencing_and_corrections/one_in_100.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pewewardy N, Severson M. A Threat to liberty: White privilege and disproportionate minority incarceration. Journal of Progressive Human Services. 2003;14:53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Próspero M. Effects of masculinity, sex, and control on different types of intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlen AB, McKelley RA, Suizzo MA, Scaringi V. Predictors of relationship satisfaction, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction among stay-at-home fathers. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2008;9:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour K. Imprisoning masculinity. Sexuality and Crime. 2003;7:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shinkfield AJ, Graffam J. Community reintegration of ex-prisoners: Type and degree of change in variables influencing successful reintegration. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2009;53:29–42. doi: 10.1177/0306624X07309757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Torrone E. Incarceration as forced migration: Effects on selected community health outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1762–1765. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp B. Fathers in jail: Managing dual identities. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice. 2009;5:26–56. [Google Scholar]

- UScourts.gov. Newly Available: Costs of Incarceration and Supervision in FY 2010. [Retrieved August 22, 2011];2011 from http://www.uscourts.gov/news/newsview/11-06-23/Newly_Available_Costs_of_Incarceration_and_Supervision_in_FY_2010.aspx.

- Williams NH. Prison health and the health of the public: Ties that bind. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2007;13:80–92. [Google Scholar]