Abstract

Electrically conducting polymers have been recognized as novel biomaterials that can electrically communicate with biological systems. For their tissue engineering applications, conducting polymers have been modified to promote cell adhesion for improved interactions between biomaterials and cells/tissues. Conventional approaches to improve cell adhesion involve the surface modification of conducting polymers with biomolecules, such as physical adsorption of cell adhesive proteins and polycationic polymers, or their chemical immobilization; however, these approaches require additional multiple modification steps with expensive biomolecules. In this study, as a simple and effective alternative to such additional biomolecule treatment, we synthesized amine-functionalized polypyrrole (APPy) that inherently presents cell adhesion-supporting positive charges under physiological conditions. The synthesized APPy provides electrical activity in a moderate range and a hydrophilic surface compared to regular polypyrrole (PPy) homopolymers. Under both serum and serum-free conditions, APPy exhibited superior attachment of human dermal fibroblasts and Schwann cells compared to PPy homopolymer controls. Moreover, Schwann cell adhesion onto the APPy copolymer was at least similar to that on poly-L-lysine treated PPy controls. Our results indicate that amine-functionalized conducting polymer substrates will be useful to achieve good cell adhesion and potentially electrically stimulate various cells. In addition, an amine functionality present on conducting polymers can further serve as a novel and flexible platform to chemically tether various bioactive molecules, such as growth factors, antibodies, and chemical drugs.

Keywords: cell adhesion, surface modification, conducting polymer, polypyrrole, scaffolds

1. Introduction

Electrically conducting polymers (CPs) have gained great attention as novel biomaterials for various biomedical applications including biosensors and tissue scaffolds[1, 2]. CPs' inherent electrical activity and conductivity have shown their unique abilities to mediate electronic or electrochemical communications between living systems and bionic devices[3, 4]. In particular, CP-based biomaterials enable electrical stimulation of cells and tissues for the modulation of cell fate, such as proliferation, differentiation, and activation[5-10]. Polypyrrole (PPy) is one of the most studied CPs for tissue engineering applications because of its good environmental stability, easy synthesis, and biocompatibility[11, 12]. By controlling chemical structure of pyrrole monomer (i.e., pyrrole derivatives) and dopants, physiocochemical properties and interactions of PPy with cells can be varied[13-15].

In general, an ability for biomaterials to support cell adhesion is prerequisite for their intimate interactions with living cells and tissues for tissue engineering applications[16, 17]. To this end, CP-based substrates have been modified to improve cell-substrate interactions by promoting cell adhesion[13, 14, 18-22]. Conventional approaches to promote cell adhesion onto conducting polymers include the introduction of cell adhesive biomolecules as dopants, and chemical conjugation or physical adsorption of cell adhesive molecules (e.g., fibronectin, laminin, cell adhesive peptides)[14, 19-23]. For example, Cui et al. incorporated two peptides derived from laminin into PPy, in which these laminin-derived peptides were doped in oxidized PPy films during electrochemical polymerization[24]. This peptide-incorporated bioactive PPy film led to higher neuron density on the films compared to the PPy controls doped with poly(styrene sulfonate). Also, affinity peptides (T59) that have specific binding to chloride-doped PPy were used to non-chemically tether extracellular matrix component-derived peptides and to promote PC12 adhesion[25, 26]. For chemical modification of PPy, Lee et al. synthesized carboxylic acid-functionalized PPy and chemically tethered fibronectin derived peptide, RGD, onto the carboxylic group presented on the PPy surfaces to promote human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) adhesion [14]. However, these immobilization methods of cell adhesive biomolecules onto PPy require expensive peptides and/or multiple conjugation steps. Hence, a simple and effective cell adhesive conducting biomaterial, which does not need additional biomolecule treatment for cell adhesion, is highly desirable.

Amine functionalities on biomaterials, in general, have been used to encourage cell adhesion by providing positive charges on surfaces under physiological conditions[27-29]. For example, positively charged electrolytes, such as poly-lysine and polyethyleneimine, have been commonly used to make a variety of material surfaces, including conducting polymers, capable of permitting cell adhesion[30]. Based on this fact, we aimed to synthesize amine functionalized conducting substrates that inherently present positive charges under physiological conditions, which could potentially replace use of additional treatments with exogenous cell adhesive substances (e.g., poly-lysine and laminin). In this study, we synthesized an amine-functionalized pyrrole derivative (i.e., 1-aminopropyl pyrrole) and electrochemically synthesized polymer films with various compositions of pristine pyrrole monomer (Py) and 1-aminopropylpyrrole (APy):

The resultant films were characterized to confirm the presence of amine groups on the surfaces and electroactivity. In vitro culture of fibroblasts and Schwann cells was performed to study cell adhesion on the amine-functionalized PPy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All chemicals, cell culture supplements, and disposable tissue culture supplies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Hyclone, and BD, respectively, unless otherwise noted.

2.2. Synthesis of 1-aminopropyl Pyrrole

1-aminopropyl pyrrole (AP) was synthesized as previously described in other literature[31, 32]. Briefly, 41 mmol of 1-(2-cyanoethyl)pyrrole (Sigma) was added dropwise into 300 mL of 0.1 mol LiAlH4 (Aldrich) in diethyl ether (Sigma). The solution was refluxed overnight and the reaction was terminated by dropwise addition of 3.4 mL of double de-ionized (DDI) water, 7 mL of 20% NaOH, and 3.4 mL DDI water. The solution was filtered and dried in a vacuum oven for 2 days. A yellow oily product was obtained and stored under N2 at -20°C until use. The product was characterized by 1H NMR (ESI Fig S1) according to the literature[31].

2.3. Electrochemical polymerization of PPy copolymer films

Polypyrrole copolymers of pristine pyrrole and APy were electrochemically synthesized on gold-coated glass slides. Gold-coated glass slides were prepared by deposition of 3 nm chromium and 30 nm gold onto glass slides (25×75×1 mm, Fisher) with a thermal evaporator (Denton). Pristine pyrrole and APy were mixed in an aqueous 1 M para-toluene sulfonic acid (Acros) solution with total concentration at 50 mM. Molar ratios (pyrrole:APy) were varied to have 100:0, for APPy-A0 (regular PPy), 50:50 for APPy-A50, and 0:100 for APPy-A100 (Table 1). APPy films were synthesized electrochemically by applying a constant potential of 1.0 V, versus a standard calomel electrode (Fisher), for 30 s using a potentiostat (Electrochemical Analyzer, CH Instrument). A three-electrode configuration was employed with a Pt mesh as a counter electrode and a standard calomel electrode (SCE) as a reference. After deposition, the samples were washed extensively with DDI water, dried in a vacuum oven overnight, and stored in a desiccator until used.

Table 1.

Characteristics of amine-functionalized PPy films synthesized with different initial feed ratios.

| Concentration in the solution (mM) | Surface amine concentration (nmol/cm2) | Roughness (nm) | Conductivity(S/cm) | Water contact angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrrole | AP | |||||

| APPy-A0 | 50 | 0 (0%) | 0 | 13.6±3.4 | 2.4 ×10±1.2 ×10 | 83.5±6.0 |

| APPy-A50 | 25 | 25 (50%) | 56 | 20.1±6.7 | 4.9×10-1±3.3×10-1 | 77.2±2.5 |

| APPy-A100 | 0 | 50 (100%) | 421 | 16.4±8.0 | 3.1×10-3±1.5×10-3 | 67.3±1.5 |

2.4. Characterization of amine-functionalized PPy films

Static water contact angles were measured using a goniometer (Edmund Optics) assembled with a Navitar CV-M30 camera. An ultrapure water droplet (2 μL) was placed on the surface of the samples at room temperature. Three samples were used and averages ± standard deviation were reported. XPS analysis using a Kratos AXIS Ultra XPS system was performed to study surface elemental compositions. The system was operated at 1×10-9 Torr chamber pressure, 15 kV and 150 W Al X-ray source. High-resolution spectra were collected with 20 eV pass energy at takeoff angles of 90° between the sample and analyzer. Calibration of the binding energy was performed by setting the C-C/C−H component in the C1s peak at 284.7 eV. Film thickness and surface roughness were measured using a Veeco Profilometer (Dektak 6M Stylus) according to the previous literature [13]. An in-plane sampling resolution was maintained to be 0.5 μm for scanning. Conductivities of the APPy films were measured using a Jandel four-point probe (1.0 mm tip spacing) with a CH Instruments, electrochemical analyzer[13, 33]. For conductivity measurement, APPy polymer films were peeled off and transferred to non-conductive tape (3M). Conductivity (σ) of the sample was calculated from the I-V curve and thickness (t) of the sample according the following equations[13, 33],

| [1] |

where σ is the conductivity (S/cm); t is the sample thickness (cm); k is a geometric constant (k=π/ln2=4.532). Three samples were used and averages ± standard deviation are reported. Surface amine concentration was quantified using ninhydrin reagents[34]. In brief, 2 mL of 2% ninhydrin solution (Sigma) was added into a screw-capped vial containing a 1 cm × 1 cm piece of each sample. The vial was boiled in a water bath for 15 min. Absorbance of the solution was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. Standard solutions were prepared using APy and their absorbance was measured. Surface amine concentration was calculated from the absorbance of the sample solution. Three samples were used and averages ± standard deviation are reported.

2.5. In vitro cell culture experiments

2.5.1. Isolation and maintenance

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (nHDF, Lonza) were maintained in T-75 tissue culture flasks (Corning) with 5% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Hyclone) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and passaged every week. Schwann cells were isolated from neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) according to previous protocol[35]. Isolated Schwann cells were maintained in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, 30 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen), and 2 μM forskolin (Sigma). Purity of Schwann cells was confirmed > 99% by immunostaining with anti-S100 antibody (Dako).

2.5.2. Adhesion studies

For cell culture experiments, all samples were UV sterilized for at least 1 hour. Some samples (as controls) were treated with poly-L-lysine (50 μg/mL) for 2 hours at room temperature to compare with cell adhesion on amine-functionalized PPy substrates. The samples were washed two times with sterile DDI water. Cells, either nHDFs or Schwann cells, were suspended in medium and seeded onto the substrate at a density of 3×104 cells/cm2. The nHDFs were cultured in serum-free DMEM (1% penicillin-streptomycin) or in serum containing DMEM (10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin). Schwann cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM (Hyclone) containing 10% FBS, 30 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 2 μM forskolin (Sigma), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cell adhesion was quantified using the CellTiter® 96 aqueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay (MTS kit, Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Four hours after seeding, the substrates were gently washed with sterile PBS to remove unbound or loosely-bound cells. Then, a mixture of serum-free culture medium and MTS reagent solution (5:1) was added into each well. After 2 hour incubation, absorbance of the medium was measured at 490 nm. At least five samples were used and averages ± standard deviation are reported.

2.5.3. Immunofluorescence

Adherent cells were stained using a calcein-AM dye (Invitrogen). Cells were aspirated and washed with PBS, followed by incubation with 2 μM calcein-AM in PBS for 15 min. Viable adherent cells were stained green. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (IX-70, Olympus) equipped with a color CCD camera (Optronics MagnaFire).

2.6. Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated using one-way analysis of variance analysis (ANOVA) for comparisons between three or more groups and a Student's t-tests for comparisons between two groups with Origin software (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). The criterion for statistical significance was p<0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of amine-functionalized PPy films

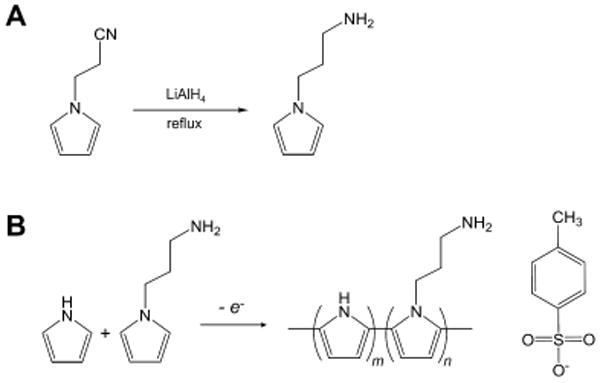

To prepare amine-functionalized PPy polymer films, APy was first synthesized by reduction of 1-(2-cyanoethyl)pyrrole using LiAlH4 (Figure 1a). Then, homopolymers of pristine pyrrole (APPy-A0) and APy (APPy-A100), and their copolymer (APPy-A50) were electrochemically polymerized at a constant potential of 1 V for 30 s (Figure 1b). We synthesized the PPy copolymer films (APPy-A50) with the same initial molar concentrations of pristine pyrrole (25 mM) and AP (25 mM) in the feed (Table 1). Thicknesses of the synthesized films were 9.4±7.9, 2.6±0.3, and 1.2±0.8 μm for APPy-A0, APPy-A50, and APPy-A100, respectively.

Figure 1.

Chemistry for amine-functionalized PPy substrates. (A) Chemistry of 1-aminopropylpyrrole (APy) synthesis from 1-(2-cyanoethyl) pyrrole. (B) A scheme of the electrochemical synthesis of copolymers of pyrrole and APy.

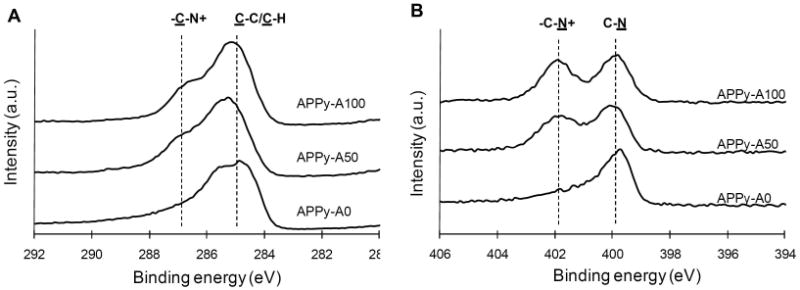

Surface amine groups on the PPy films were quantified using a ninhydrin assay (Table 1). Incorporation of AP into PPy substrates significantly resulted in color changes in ninhydrin solution, whereas pristine PPy films (APPy-A0) did not lead to substantial color change with the reagent. APPy-A100 and APPy-A50 had 421 and 56 nmol of amine per cm2 substrates, respectively. APPy-A50, polymerized from equimolar pyrrole and AP (25 mM each), showed 13% surface amine group compared to that of APPy-A100. This indicates that the pyrrole derivative, AP, was poorly incorporated into copolymer films compared to pristine pyrrole. This unfavorable incorporation of pyrrole derivatives has been widely observed, which results from steric hindrance of the bulky side chain during polymerization[4, 14, 33]. Surface elements on the APPy films were characterized by XPS. Peak assignments were made according to literature[36-38]. Introduction of amine functionality changed both carbon and nitrogen spectra of C1s and N1s (Figure 2). In the C1s spectra, peaks observed in the range of 286.5 – 287.2 eV correlate to amino carbons in the amine functionalized polypyrrole. For example, the peak (C-N+) at 287 eV became prominent in APPy-A50 and APPy-A100. Likewise, positively charged nitrogen atoms (C-N+) were newly detected around 401.9 eV in the N1s spectra for the amine functionalized polypyrrole films. These spectroscopic analyses further confirmed the presence of amine functionality at the APPy surfaces. The amine functionalities presented on the APPy-A50 and APPy-A100 substrates will exhibit positive charges under physiological conditions and can be potentially employed for chemically conjugating various bioactive ligands, such as peptides, growth factors, antibodies, and chemical drugs, onto the aminated surfaces.

Figure 2.

High resolution (A) C1s and (B) N1s XPS spectra of regular PPy (APPy-A0) and amine-functionalized PPy copolymer (APPy-A50 and APPy-A100) films. The dashed lines in (A) and (B) indicate the peaks related to C-N+.

As expected, presentation of amine functionality on the PPy substrates influenced wettability (Table 1. ESI Figure S2). The amine-functionalized PPy (APPy-A50 and APPy-A100) exhibited lower water contact angles compared to the regular PPy (APPy-A0). With increases in surface amine concentrations, the surfaces became more hydrophilic. APPy-A100 and APPy-A50 had contact angles of 67.3±1.5° and 77.2±2.5°, respectively. Increased wettability of the amine-functionalized PPy is attributed to an increase in hydrophilic moiety (i.e., primary amine) on the APPy films. Hydrophilicity as well as surface charges of biomaterials affects cell adhesion and proliferation and can improve biocompatibility[39, 40]. In general, hydrophobic surfaces induce denaturation of adsorbed proteins by altering their structures[41]. Incorporation of APy into PPy led to a drastic decrease in conductivity (Table 1. ESI Figure S3). APPy-A100 and APPy-A50 exhibited four- and two-orders of magnitude decrease in conductivity, respectively, compared to regular PPy (APPy-A0). Although amine-functionalized conducting polymers are useful to enhance cell adhesion or chemically tether molecules, a severe decrease in conductivity may limit their applications that require high electrical sensitivity and conductivity. Thus, two properties, conductivity and functionality, have to be considered together and optimized according to applications. The amine-functionalized PPy films, especially APPy-A50, would be useful because of their moderate ranges of conductivity that can be sufficient for electrical stimulation of cells [14, 42]. Roughness of the copolymer films was 13.6±3.4, 20.1±6.7, and 16.4±8.0 nm for APPy-A0, APPy-A50, and APPy-A100, respectively. Roughness of regular PPy and APPy films were similar without substantial differences (Table 1), which allows us to rule out the possible topographical effects of APPy on cell adhesion when studying the relationship between surface amine functionality and cell adhesion.

3.2 Cell Adhesion onto amine-functionalized PPy

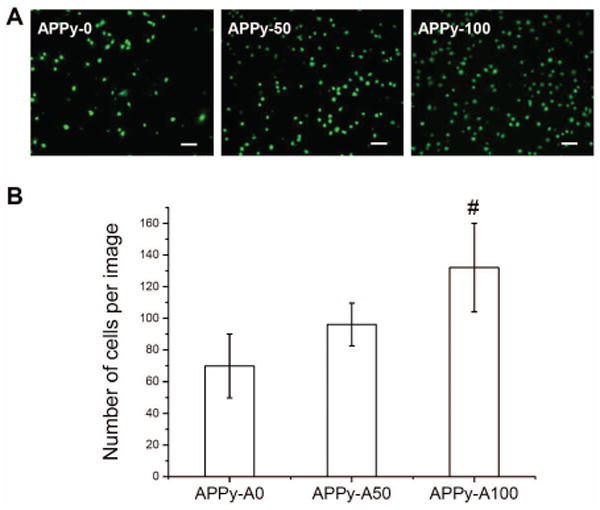

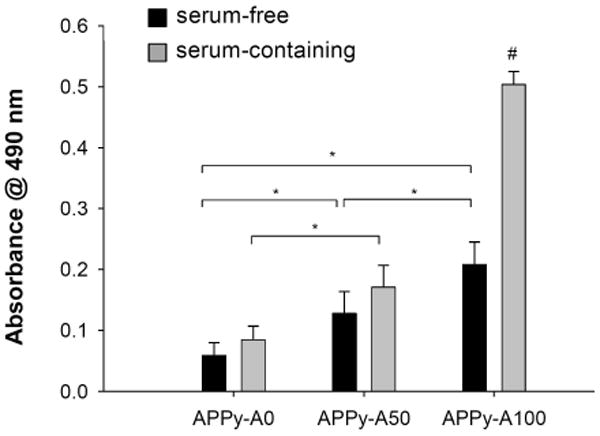

Fibroblasts were cultured on PPy substrates to study cell adhesion. Fibroblasts are one of the most studied cells for adhesion on various biomaterials[43-45]. First, fibroblast cell adhesion onto the APPy substrates was tested in a serum-free environment. As shown in Figure 3, fibroblasts adhered well onto the sample surfaces and were viable. With an increase in surface amine groups, more cells adhered. Quantitative analysis was performed using an MTS assay, which measures the metabolic activity of viable cells to reduce MTS to a colorimetric formazan product[46]. Results indicated a significant increase in attached fibroblasts on the amine-functionalized PPy films over unmodified PPy films in serum-free medium (Figure 4). The MTS assay results showed a similar trend to cell counting (ESI Fig S2), indicating the relevance of a viability assay for the quantification of adhered cells. It can be suggested that enhanced cell adhesion on the amine-functionalized PPy may result from charge-charge interactions between the cell membrane and the amine-functionalized substrates. Most cell membranes are negatively charged; thus positively charged substrates can help anchor cells onto the substrata[30]. Next, cell adhesion was also studied in serum-containing medium. Significantly increased cell adhesion on all samples in serum-containing medium was observed compared to that in serum-free medium. This increased cell adhesion in serum-containing medium implies that fibroblast adhesion onto the APPy substrates can be mediated by the adsorption of cell adhesive proteins (e.g., fibronectin and laminin) present in serum as well as the charge interactions. Several studies reported that adsorption of cell adhesive extracellular matrix proteins increase on positively charged material surfaces[28, 47, 48]. Therefore, cell adhesive proteins may absorb more onto the hydrophilic amine-functionalized surfaces and then promote cell adhesion, indicating the cooperative roles of serum proteins and positively charged surfaces in cell adhesion. However, further studies should be performed to clearly understand the mechanisms of improved cell adhesion onto the amine-functionalized PPy in the presence of serum by exploring adsorption of specific proteins and their molecular conformations onto the substrates after adsorption.

Figure 3.

Fibroblast adhesion on the amine-functionalized PPy copolymers. (A) Representative fluorescence images of fibroblasts cultured in serum free medium on APPy-A0, APPy-A50, and APPy-A100. Four hours after seeding, the samples were incubated in calcein AM solution to stain cytoplasm of living fibroblasts. Scale bars are 100 μm. (B) Numbers of fibroblasts on the APPy substrates. The numbers of cells were counted from randomly acquired fluorescence images. Each bar and represents the average ± standard deviation (n≥5). A pound (#) denotes a statistical significance among all groups (p<0.05)

Figure 4.

Quantitative cell viability assay of fibroblast adhesion on of regular PPy (APPy-A0) and amine-functionalized PPy copolymer (APPy-A50 and APPy-A100) films. Fibroblasts were seeded onto substrates in either serum-containing or serum-free medium. After 4 hour incubation, an MTS assay was performed. Each bar represents the average ± the standard deviation (n≥6). A pound (#) denotes a statistical significance among all groups (p<0.01), and an asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance between two groups (p<0.05).

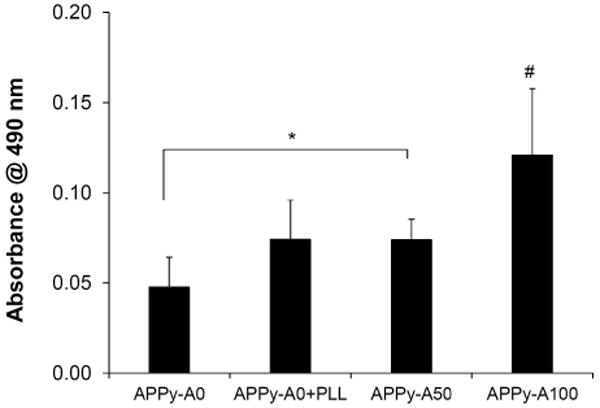

In addition, we tested adhesion of Schwann cells onto the aminated conducting polymers. Schwann cells are glial cells found in peripheral nerve. These cells play essential roles in regenerating damaged peripheral nerve tissue, which include guidance of axon growth, secretion of neurotrophins, and providing contacts with neurons/axons[49, 50]. A recent report demonstrated that electrical stimulation of Schwann cells through PPy-based biomaterials enhanced brain-derived nerve growth factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) secretion[51, 52]. Thus, improvement of Schwann cell attachment onto conducting substrates can potentially allow fabricating and employing electrically conducting scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering applications. We prepared additional control samples by treating regular PPy (APPy-A0) with 50 μg/mL poly-L-lysine (PLL) solution to compare the ability of the APPy to support Schwann cell adhesion. Similar to fibroblasts, more Schwann cells were found on the amine-functionalized PPy substrates (Figure 5). APPy-A100 was superior to other samples in Schwann cell adhesion (p<0.01). Adhesion of Schwann cells on APPy-A50 was significantly higher than that on untreated APPy-A0 and similar to that on PLL-treated APPy-A0. The results demonstrate that the amine-functionalized PPy films are effective for Schwann cell adhesion. Importantly, our conducting biomaterials, inherently presenting cell-adhesive surface properties, can save efforts and cost for additional treatment with cell adhesive biomolecules (e.g., PLL, laminin, and fibronectin).

Figure 5.

Adhesion of Schwann cells on the amine-functionalized PPy films and PLL-treated (50 μg/mL) regular PPy films. Experiments were performed and evaluated in an analogous manner to the fibroblast adhesion study. Each bar represents the average ± the standard deviation (n≥5). A pound (#) denotes a statistical significance among all groups (p<0.01), and an asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance between two groups (p<0.05).

4. Conclusion

Cellular interactions with biomaterials are critical in tissue engineering applications. Initial adhesion of cells onto biomaterial scaffolds determines integration of biomaterials. Accordingly, conducting polymers have been modified to promote cell adhesion for their improved interactions with cells/tissues. In this study, inherent positive charges were introduced into the PPy structure by polymerizing amine-functionalized pyrrole to improve adhesion of fibroblasts and Schwann cells onto the conducting substrates. Addition of serum in culture could further improve fibroblast adhesion onto the amine-functionalized PPy. These amine-functionalized conducting films may replace use of conventional polymeric cations (e.g., PLL) for the promotion of cell adhesion on CPs. In addition, these amine-functionalized PPy substrates can serve as a platform to chemically conjugate various bioactive ligands, such as ECM proteins/peptides, growth factors, antibodies, and chemical drugs, for various biomedical applications (e.g., biosensors, scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01EB004429. This research was also supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2013R1A1A1012179).

References

- 1.Guimard NK, Gomez N, Schmidt CE. Conducting polymers in biomedical engineering. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:876–921. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy JG, Lee JY, Schmidt CE. Biomimetic conducting polymer-based tissue scaffolds. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace GG, Higgins MJ, Moulton SE, Wang C. Nanobionics: the impact of nanotechnology on implantable medical bionic devices. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4327–4347. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30758h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendrea AD, Cianga L, Cianga I. Review paper: Progress in the field of conducting polymers for tissue engineering applications. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 2011;26:3–84. doi: 10.1177/0885328211402704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt CE, Shastri VR, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth using an electrically conducting polymer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8948–8953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forciniti L, Ybarra J, 3rd, Zaman MH, Schmidt CE. Schwann cell response on polypyrrole substrates upon electrical stimulation. Acta Biomater. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Nishizawa M, Nozaki H, Kaji H, Kitazume T, Kobayashi N, Ishibashi T, Abe T. Electrodeposition of anchored polypyrrole film on microelectrodes and stimulation of cultured cardiac myocytes. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1480–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooney E, Mackle JN, Blond DJ, O’Cearbhaill E, Shaw G, Blau WJ, Barry FP, Barron V, Murphy JM. The electrical stimulation of carbon nanotubes to provide a cardiomimetic cue to MSCs. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6132–6139. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JY, Bashur CA, Goldstein AS, Schmidt CE. Polypyrrole-coated electrospun PLGA nanofibers for neural tissue applications. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4325–4635. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowlands AS, Cooper-White JJ. Directing phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells using electrically stimulated conducting polymer. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4510–4520. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ateh DD, Navsaria HA, Vadgama P. Polypyrrole-based conducting polymers and interactions with biological tissues. J R Soc Interface. 2006;3:741–752. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang X, Marois Y, Traore A, Tessier D, Dao LH, Guidoin R, Zhang Z. Tissue reaction to polypyrrole-coated polyester fabrics: an in vivo study in rats. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:635–847. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonner JM, Forciniti L, Nguyen H, Byrne JD, Kou YF, Syeda-Nawaz J, Schmidt CE. Biocompatibility implications of polypyrrole synthesis techniques. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:034124. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JW, Serna F, Nickels J, Schmidt CE. Carboxylic acid-functionalized conductive polypyrrole as a bioactive platform for cell adhesion. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1692–1695. doi: 10.1021/bm060220q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson BC, Moulton SE, Richardson RT, Wallace GG. Effect of the dopant anion in polypyrrole on nerve growth and release of a neurotrophic protein. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3822–3831. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tirrell M, Kokkoli E, Biesalski M. The role of surface science in bioengineered materials. Surf Sci. 2002;500:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.del Valle LJ, Estrany F, Armelin E, Oliver R, Aleman C. Cellular adhesion, proliferation and viability on conducting polymer substrates. Macromol Biosci. 2008;8:1144–1151. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng S, Rouabhia M, Shi G, Zhang Z. Heparin dopant increases the electrical stability, cell adhesion, and growth of conducting polypyrrole/poly(L,L-lactide) composites. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:332–344. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green RA, Lovell NH, Poole-Warren LA. Cell attachment functionality of bioactive conducting polymers for neural interfaces. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3637–3644. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao Y, Li CM, Wang S, Shi J, Ooi CP. Incorporation of collagen in poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for a bifunctional film with high bio- and electrochemical activity. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92:766–772. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Yue Z, Higgins MJ, Wallace GG. Conducting polymers with immobilised fibrillar collagen for enhanced neural interfacing. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7309–7317. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stauffer WR, Cui XT. Polypyrrole doped with 2 peptide sequences from laminin. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2405–2413. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui X, Lee VA, Raphael Y, Wiler JA, Hetke JF, Anderson DJ, Martin DC. Surface modification of neural recording electrodes with conducting polymer/biomolecule blends. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;56:261. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200108)56:2<261::aid-jbm1094>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanghvi AB, Miller KP, Belcher AM, Schmidt CE. Biomaterials functionalization using a novel peptide that selectively binds to a conducting polymer. Nat Mater. 2005;4:496–502. doi: 10.1038/nmat1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nickels JD, Schmidt CE. Surface modification of the conducting polymer, polypyrrole, via affinity peptide. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:1464–1471. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JH, Jung HW, Kang IK, Lee HB. Cell behaviour on polymer surfaces with different functional groups. Biomaterials. 1994;15:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb K, Hlady V, Tresco PA. Relationships among cell attachment, spreading, cytoskeletal organization, and migration rate for anchorage-dependent cells on model surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;49:362–368. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000305)49:3<362::aid-jbm9>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgenthaler S, Zink C, Stadler B, Voros J, Lee S, Spencer ND, Tosatti SG. Poly(L-lysine)-grafted-poly(ethylene glycol)-based surface-chemical gradients. Preparation, characterization,and first applications. Biointerphases. 2006;1:156–165. doi: 10.1116/1.2431704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazia D, Schatten G, Sale W. Adhesion of cells to surfaces coated with polylysine. Applications to electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1975;66:198–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.66.1.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JY, Schmidt CE. Pyrrole-hyaluronic acid conjugates for decreasing cell binding to metals and conducting polymers. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4396–4404. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajesh, Bisht V, Takashima W, Kaneto K. An amperometric urea biosensor based on covalent immobilization of urease onto an electrochemically prepared copolymer poly (N-3-aminopropyl pyrrole-co-pyrrole) film. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3683–3690. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JY, Lee JW, Schmidt CE. Neuroactive conducting scaffolds: nerve growth factor conjugation on active ester-functionalized polypyrrole. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:801–810. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore S. Amino acid analysis: aqueous dimethyl sulfoxide as solvent for the ninhydrin reaction. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:6281–6283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suri S, Schmidt CE. Cell-laden hydrogel constructs of hyaluronic acid, collagen, and laminin for neural tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1703–1716. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han MG, Im SS. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of electrically conducting polyaniline/polyimide blends. Polymer. 2000;41:3253–3262. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graf N, Yegen E, Gross T, Lippitz A, Weigel W, Krakert S, Terfort A, Unger WES. XPS and NEXAFS studies of aliphatic and aromatic amine species on functionalized surfaces. Surf Sci. 2009;603:2849–2860. [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Giglio E, Guascito MR, Sabbatin L, Zambonin G. Electropolymerization of pyrrole on titanium substrates for the future development of new biocompatible surfaces. Biomaterials. 2001;22:2609. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arima Y, Iwata H. Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3074–3082. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schakenraad JM, Busscher HJ. Cell-polymer interactions: The influence of protein adsorption. Colloids Surf. 1989;42:331–343. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thevenot P, Hu W, Tang L. Surface chemistry influences implant biocompatibility. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8:270–280. doi: 10.2174/156802608783790901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mawad D, Stewart E, Officer DL, Romeo T, Wagner P, Wagner K, Wallace GG. A single component conducting polymer hydrogel as a scaffold for tissue engineering. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:2692–2699. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pennisi CP, Dolatshahi-Pirouz A, Foss M, Chevallier J, Fink T, Zachar V, Besenbacher F, Yoshida K. Nanoscale topography reduces fibroblast growth, focal adhesion size and migration-related gene expression on platinum surfaces. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;85:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei J, Yoshinari M, Takemoto S, Hattori M, Kawada E, Liu B, Oda Y. Adhesion of mouse fibroblasts on hexamethyldisiloxane surfaces with wide range of wettability. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;81:66–75. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenbarth E, Meyle J, Nachtigall W, Breme J. Influence of the surface structure of titanium materials on the adhesion of fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1399–1403. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)87281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cory AH, Owen TC, Barltrop JA, Cory JG. Use of an aqueous soluble tetrazolium/formazan assay for cell growth assays in culture. Cancer Commun. 1991;3:207–212. doi: 10.3727/095535491820873191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson CJ, Clegg RE, Leavesley DI, Pearcy MJ. Mediation of biomaterial-cell interactions by adsorbed proteins: a review. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1–18. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keselowsky BG, Collard DM, García AJ. Surface chemistry modulates focal adhesion composition and signaling through changes in integrin binding. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5947–5954. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Son YJ, Trachtenberg JT, Thompson WJ. Schwann cells induce and guide sprouting and reinnervation of neuromuscular junctions. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:280–285. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt CE, Leach JB. Neural tissue engineering: strategies for repair and regeneration. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2003;5:293–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang J, Hu X, Lu L, Ye Z, Zhang Q, Luo Z. Electrical regulation of Schwann cells using conductive polypyrrole/chitosan polymers. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93:164–174. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koppes AN, Nordberg AL, Paolillo GM, Goodsell NM, Darwish HA, Zhang L, Thompson DM. Electrical stimulation of Schwann cells promotes sustained increases in neurite outgrowth. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:494–506. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.