Abstract

Background

Genetically modified pigs are a promising potential source of lung xenografts. Ex-vivo xenoperfusion is an effective platform for testing the effect of new modifications, but typical experiments are limited by testing of a single genetic intervention and small sample sizes. The purpose of this study was to analyze the individual and aggregate effects of donor genetic modifications on porcine lung xenograft survival and injury in an extensive pig lung xenoperfusion series.

Methods

Data from 157 porcine lung xenoperfusion experiments using otherwise unmodified heparinized human blood were aggregated as either continuous or dichotomous variables. Lungs were wild type in 17 perfusions (11% of the study group), while 31 lungs (20% of the study group) had 1 genetic modification, 40 lungs (39%) had 2, and 47 lungs (30%) had 3 or more modifications. The primary endpoint was functional lung survival to 4 hours of perfusion. Secondary analyses evaluated previously identified markers associated with known lung xenograft injury mechanisms. In addition to comparison among all xenografts grouped by survival status, a subgroup analysis was performed of lungs incorporating the GalTKO.hCD46 genotype.

Results

Each increase in the number of genetic modifications was associated with additional prolongation of lung xenograft survival. Lungs that exhibited survival to 4 hours generally had reduced platelet activation and thrombin generation. GalTKO and the expression of hCD46, HO-1, hCD55 or hEPCR were associated with improved survival. hTBM, HLA-E, and hCD39 were associated with no significant effect on the primary outcome.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis of an extensive lung xenotransplantation series demonstrates that increasing the number of genetic modifications targeting known xenogeneic lung injury mechanisms is associated with incremental improvements in lung survival. While more detailed mechanistic studies are needed to explore the relationship between gene expression and pathway-specific injury, and explore why some genes apparently exhibit neutral (hTBM, HLA-E) or inconclusive (CD39) effects, GalTKO, hCD46, HO-1, hCD55, and hEPCR modifications were associated with significant lung xenograft protection. This analysis supports the hypothesis that multiple genetic modifications targeting different known mechanisms of xenograft injury will be required to optimize lung xenograft survival.

Introduction

Porcine lung xenografts are a promising alternative to critically scarce human allografts if innate immunologic barriers can be overcome. 1–3 Genetically modified heart, lung, kidney and islet xenografts have contributed to improved survival in pre-clinical models. 3–8 In particular, knocking out the α-1,3 galactosyl transferase gene (GalTKO) prevents expression of galactose 1,3α-galactose (Gal), 9,10 the primary target of pre-formed human anti-pig antibodies. 11 Transgenic expression of human proteins responsible for regulating critical complement pathways (hCD46, hCD55, hCD59) have also demonstrated efficacy in various models. 12–18 Targeting prothrombotic and inflammatory pathways (hTBM, hEPCR, hCD39, HO-1) and adhesive interactions (HLA-E) have been proposed to suppress additional mechanisms of xenograft injury, some of which arise from interspecies molecular incompatibilities. 3,19–24

Ex-vivo perfusion with human blood is a mechanistically informative whole-organ model of clinical pig-to-human xenotransplantation, and a platform for studying mechanisms of lung xenograft injury and testing genetic and pharmacologic interventions. 1,25 Our group has previously reported the effects of several genetic and pharmacologic interventions on lung xenograft performance during ex-vivo perfusion with human blood. 12,16,22,26,27 Although traditional experiments using this model have contributed to major advances in the field, with the exception of a few reports, such as the analysis of the GalTKO.hCD46 genotype by Burdorf et al, 12 they are typically limited to assessment of a single intervention with small sample sizes, constraining statistical power. Importantly, as the number of available, rationally targeted genetic modifications increases, 1,19 the ability to measure the efficacy of each modification against multiple relevant “reference” genotypes becomes increasingly complicated by logistical challenges, model constraints, and resource limitations. Based on remarkable advances in genetic engineering, in the span of two years the genotype of pigs available has progressed from GalTKO.hCD46 to include up to six genetic modifications in varying combinations. As such, potentially important effects associated with recent genetic interventions may not be apparent using traditional “head-to-head” experimental approaches, particularly when the number of experiments with particular multi-gene phenotypes is small.

In the course of our lab’s lung xenotransplantation research, we have performed nearly 400 ex-vivo porcine lung perfusion experiments. The purpose of the current study was to analyze this aggregate data set for trends associated with lung xenograft failure or survival among pig donors with various genetic modifications, each of which is designed to attenuate injury associated with one or more pathways known to drive acute lung xenograft injury. Here we present a “meta-analysis” of our ex-vivo xenoperfusion experience, using the context of the large data set to ask in an exploratory manner whether specific genetic modifications appear to contribute significantly to improve acute lung xenograft survival. 1

Methods

Animal care and procedures were in compliance with National Institute of Health guidelines, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee; the Institutional Review Board approved human blood collection and use. Most genetically engineered pigs were obtained from Revivicor (Blacksburg, VA). Exceptions included some GalTKO, hCD55, and GalTKO.hCD55 transgenic animals, which were sourced from Imutran - Novartis USA or Immerge Biotherapeutics (Charlestown, MA), directly or via the National Swine Research Resource Center, and GalTKO.hCD39 pigs which were imported from St. Vincents Hospital (Sydney, Australia). The GalTKO.hCD46.HLAE pigs were produced by crossbreeding and cloning of Revivicor GalTKO.hCD46 pigs with HLAE transgenic pigs originally generated through collaboration with Eckhard Wolf, Nikolai Klymuik, and Andrea Bahr at Ludwig Maximilians University (LMU; Munich, Germany). Finally, a limited number of GalTKO.hCD46.hTBM pigs were cloned by Revivicor using transgenic cells developed at LMU. 28

In most (but not all) cases, founder animals were prescreened by the supplier to confirm expression of each test gene in promoter-appropriate locations. When possible, lines with high levels of expression in the lung were typically selected, and generated for lung perfusion experiments by cloning or breeding. However, in other transgenic lines (hCD39, HO1, EPCR, and pigs with four or more modifications), founder animals were produced, and expression was therefore only evaluated in peripheral blood cells (PBMC) of transgenic pigs pre-perfusion, and thus might have variable expression in the lung. Results for most of the individual wild type, hCD55, hCD46, GalTKO, and GalTKO.hCD46 xenoperfusion experiments have previously been reported in peer-reviewed journals. 12,16,26,27 Most experiments using pigs with three or more genetic modifications have been presented orally and published in abstract form.

Our ex-vivo lung xenoperfusion technique has been previously described and was performed consistently between experiments; those performed under separate protocols or experiencing technical failures were excluded. 12,16,25,26,29 Briefly, the proximal pulmonary artery was cannulated via median sternotomy following systemic heparinization,. After treatment with the thromboxane synthase inhibitor 1-benzylimidazole and synthetic prostaglandin E2 or I2 (as alprostadil, epoprostenol or treprostinil), the lungs were flushed with 4°C Perfadex (XVIVO; Göteborg, Sweden). The heart and lung block was explanted, and the lungs prepared for independent ventilation and perfusion of the right and left lungs in side-by-side independent circuits.

Lungs were perfused with heparinized, freshly collected whole human blood expanded with ABO blood type-matched human plasma; typically approximately 900 ml of whole blood from two volunteer donors was combined with four 240 ml units of “recovered” frozen plasma, with 60% of the pooled blood perfusate apportioned to the right lung circuit based on relative lung weight. Heparin is required in this model to prevent blood coagulation on contact with the mechanical circuit; lungs exposed to pharmacologic or other manipulations beyond perfusate heparinization were excluded from this analysis. Pulmonary vascular resistance was monitored continuously, and blood samples were obtained from the pulmonary venous effluent at predefined intervals. In-vitro analyses included: β-thromboglobulin (βTG), plasma prothrombin fragments 1 & 2 (F1+2), and thromboxane levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; complete blood counts by automated counter; and CD62p expression by flow cytometry. Other previously reported parameters, such as histamine elaboration and complement activation, were not routinely measured across all experiments, and were thus not included in this analysis.

The endpoint of each experiment was functional survival to 4 hours of xenoperfusion; lung failure was defined as tracheal edema with fluid preventing ventilation and/or perfusate sequestration in the lung (indicating loss of vascular barrier function), supra-physiologic rise in pulmonary vascular resistance (a proxy for right heart failure in vivo), or absence of oxygen step-up across the lung (indicating failure of gas exchange). The primary outcome was functional lung survival to 4 hours, assessed both categorically and continuously by survival time censored at 4 hours for occasional recent experiments where perfusion was continued for longer intervals.

Experimental conditions (e.g. presence of individual genetic modifications) and outcomes were dichotomized. The main analysis was between the effects of genetic modifications on survival. Because the GalTKO.hCD46 genetic platform has become the background genotype for subsequent research by our group and others based on our recent report of its efficacy, 12 a subgroup analysis of lungs incorporating this genotype was also performed.

Statistical analyses were performed using Instat (Graphpad; LaJolla, CA), Excel (Microsoft; Redmond, WA), and SigmaPlot (Systat; San Jose, CA). Categorical data were compared in a univariate fashion by two-sided Fisher exact tests, and for modifications present in more than 5% of the group the individual effect of each intervention on the primary outcome was assessed by multivariable logistic regression. Survival times were compared by log-rank test. Two-way analysis of continuous variables was by unpaired Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test for normally and non-normally distributed data, while multiple comparisons were performed using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn’s post-test. All continuous data are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. An independent biostatistician reviewed the statistical approach.

Results

There were 355 separate ex-vivo lung xenoperfusions performed by our group between August 2003 and April 2014. 14 (4%) lungs procured by other teams and sent to our center for xenoperfusion, and 183 (52%) lungs perfused with pharmacologic treatments in addition to heparin were excluded from this analysis. Further, 1 untreated lung failed from technical reasons and was censored. The genotypes of the 157 untreated lungs included for analysis are summarized in Table 1; 77 (49%) have been reported in previous publications. 12,16,26,27 140 (89%) lungs came from genetically modified pigs, consisting of 9 different gene modifications in 14 genotypic combinations. 96 (61%) lungs included the GalTKO.hCD46 genotype, with 47 (49%) of these expressing one or more additional transgenes.

Table 1.

Summary of lung xenograft genetics and outcomes.

| Characteristic | Lung xenografts |

|---|---|

| n | 157 |

| Genetic modifications, % (n) | |

| GalTKO | 83 (130) |

| hCD46 | 61 (96) |

| hCD55 | 19 (30) |

| hCD39 | 7 (11) |

| hEPCR | 6 (9) |

| hTBM | 9 (14) |

| HLA-E | 5 (8) |

| hHO-1 | 2 (3) |

| Genotypes, % (n) | |

| WT | 11 (17) |

| hCD55 | 6 (10) |

| GalTKO | 13 (21) |

| GalTKO.hCD39 | 4 (6) |

| GalTKO.hCD55 | 4 (7) |

| GalTKO.hCD46 | 31 (49) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hCD39 | 3 (4) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hCD55 | 6 (10) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hHLA-E | 5 (8) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hHO-1 | 2 (3) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hEPCR | 4 (6) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hTBM | 8 (13) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hCD55.hEPCR | 1 (2) |

| GalTKO.hCD46.hCD55.hCD39.hEPCR.hTBM | 1 (1) |

| Outcomes | |

| Median survival time, minutes (IQR) | 150 (42 – 240) |

| 4 hours functional survival, % (n) | 35 (55) |

| Failure within 4 hours, % (n)a | 65 (102) |

| Tracheal edema | 12 (19) |

| Perfusate sequestration | 5 (8) |

| Excessive pulmonary vascular resistance | 36 (57) |

| Failed gas exchange | 4 (6) |

incomplete data for 12 lungs

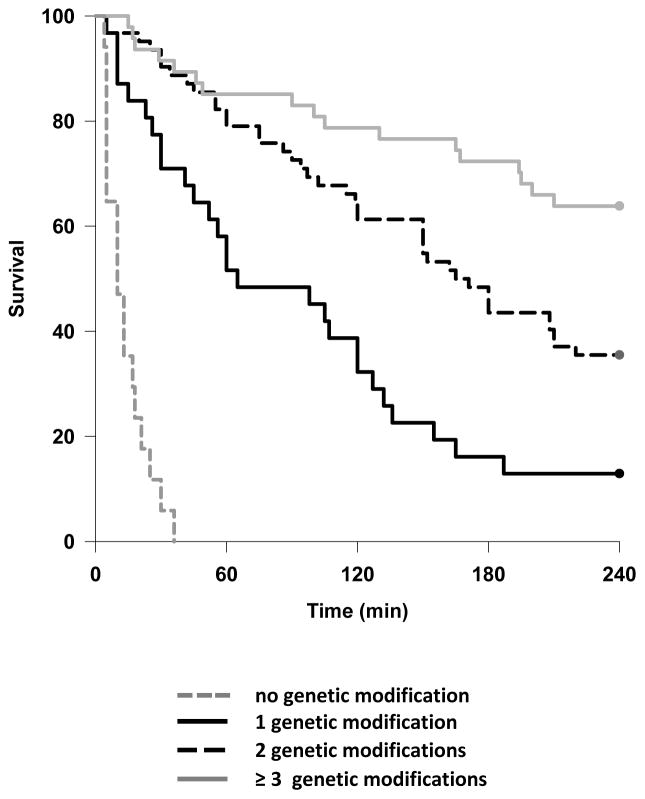

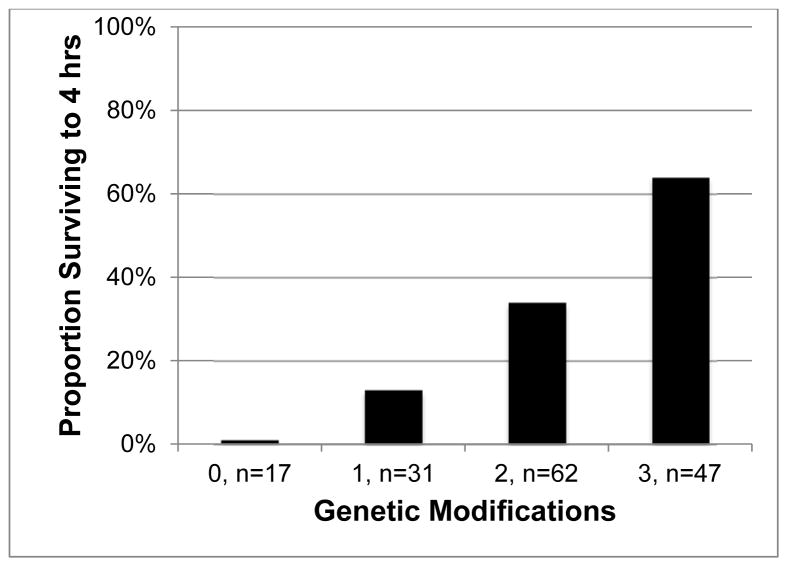

The overall median survival time was 150 (42 – 240) minutes, and 55 (35%) of lungs survived to 4 hours. As previously reported, 12,26 xenoperfused wild type (WT) lungs rapidly failed due to hyperacute rejection, primarily mediated by pre-formed human anti-Gal antibodies (Table 2). 11 Increasing numbers of genetic modifications were associated with stepwise improvements in lung survival (Figure 1), such that the majority of lungs featuring at least 3 modifications survived to the 4-hour endpoint (Figure 2 & Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes and perfusion parameters associated with cumulative genetic modifications. βTG and F1+2 levels are after 30 minutes of xenoperfusion.

| Modifications | 0, n = 17 | 1, n = 31 | 2, n = 62 | ≥3, n = 47 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median survival, min (IQR)a | 10 (5 – 18) | 65 (30 – 134) | 168 (87 – 240) | 240 (166 – 240) |

| Survival to 4 hours, % (n)b | 0 | 13 (4) | 34 (21) | 64 (30) |

| βTG, IU/mLb | 1300 (992 – 1962) | 869 (638 – 1066) | 588 (422 – 757) | 518 (385 – 584) |

| F1+2, nMb | 18 (10 – 23) | 7 (1 – 19) | 2 (1 – 3) | 2 (1 – 3) |

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Kaplan – Meier survival curve demonstrating association between cumulative genetic modifications and survival time. P < 0.01 for all inter-group comparisons.

nb: 0 modifications group represents xenoperfusion of wild type pig lungs.

Figure 2.

Association between cumulative genetic modifications and survival to 4 hours of perfusion. P < 0.0005.

nb: 0 modifications group represents xenoperfusion of wild type pig lungs.

On univariate analysis, GalTKO or expression of hCD46, hHO-1, or hEPCR were associated with prolonged lung xenograft survival (Table 3). After multivariate logistic regression, GalTKO, hCD55 and hEPCR were independently associated with improved survival (Table 4). Among GalTKO.hCD46 lungs, hCD55 and hEPCR expression remained associated with protection from injury, while hCD39, HLAE, and hTBM had no apparent protective effect on lung survival (Tables 3 & 4).

Table 3.

Association between selected individual genetic modifications and xenograft survival among all and GalTKO.hCD46 lungs.

| All Lungs | GalTKO.hCD46 Lungs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Modification, % (n) | Failed, n=102 | Survived, n=55 | P | Failed, n= 51 | Survived, n=45 | P |

| GalTKO | 74 (75) | 100 (55) | < 0.0001 | n/a | n/a | |

| hCD46 | 50 (51) | 82 (45) | < 0.0001 | n/a | n/a | |

| hCD55 | 18 (18) | 22 (12) | 0.53 | 6 (3) | 22 (10) | 0.08 |

| hCD39 | 7 (7) | 7 (4) | 1.00 | 10 (5) | 0 | 0.02 |

| HLA-E | 3 (3) | 9 (5) | 0.13 | 6 (3) | 11 (5) | 0.72 |

| hHO-1 | 0 | 5 (3) | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | |

| hEPCR | 1 (1) | 16 (8) | 0.001 | 2 (1) | 18 (8) | 0.03 |

| hTBM | 8 (8) | 11 (6) | 0.56 | 16 (8) | 13 (6) | 0.57 |

Significant differences are noted in bold font.

Table 4.

Independent effects on lung xenograft survival associated with individual genetic modifications, analyzed for all lungs (center column), and in the context of the GalTKO.hCD46 background (right column).

| Genetic Modification, OR (95% CI) | All xenografts, n = 157 | GalTKO.hCD46 xenografts, n = 96 |

|---|---|---|

| GalTKO | 1.6 (1.1 – 2.2) | n/a |

| hCD46 | 1.1 (0.9 – 1.4) | n/a |

| hCD55 | 1.2 (1.0 – 1.5) | 1.4 (1.0 – 1.8) |

| hCD39 | 1.0 (0.7 – 1.3) | 0.6 (0.4 – 0.9) |

| HLA-E | 1.3 (0.9 – 1.8) | 1.3 (0.9 – 1.8) |

| hEPCR | 1.6 (1.2 – 2.1) | 1.6 (1.1 – 2.2) |

| hTBM | 1.0 (0.8 – 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8 – 1.3) |

Significant differences are noted in bold font.

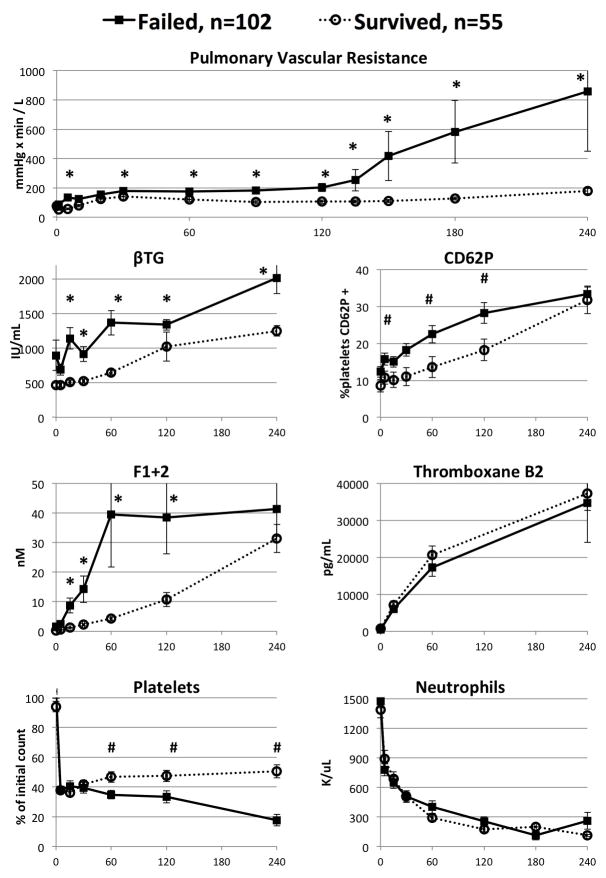

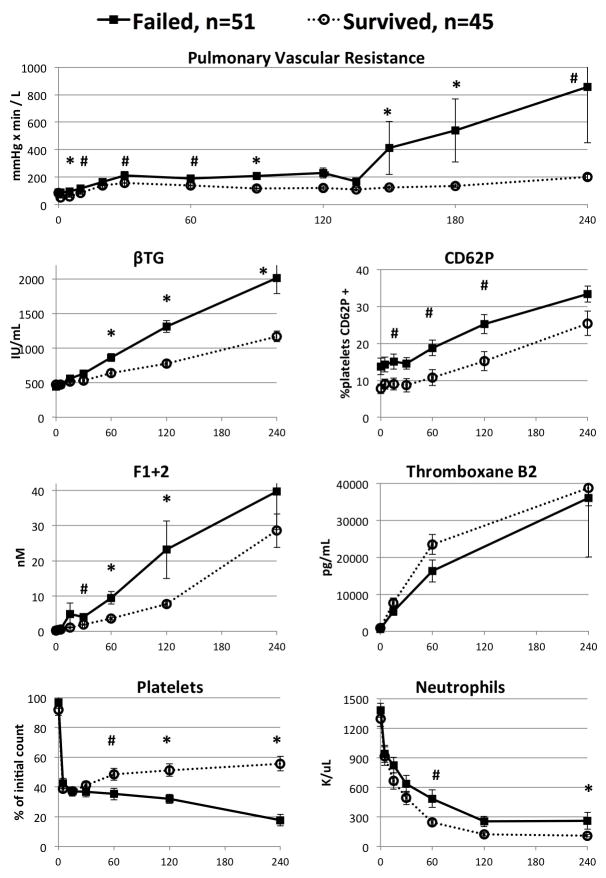

In all lungs and within the GalTKO.hCD46 subgroup, xenograft failure was associated with significantly higher pulmonary vascular resistance, thrombin formation, and platelet activation and consumption (Figures 3 & 4). In particular, by 30 minutes of perfusion, pulmonary vascular resistance, thrombin formation and platelet activation were all at least 25% higher, on average, among lungs that failed compared to lungs that survived. Along with improved survival, increasing number of genetic modifications were associated with progressive decreases in platelet activation and thrombin generation (Table 2). However, other factors, such as pulmonary vascular resistance, thromboxane generation, and platelet and neutrophil sequestration were generally not attenuated in association with increasing the number of lung genetic modifications tested here.

Figure 3.

Perfusion parameters for parameters for all lungs, segregated by lung failure within four hours versus lungs surviving at four hours. X axis represents perfusion time in minutes. #: P < 0.05, *: P < 0.005

Figure 4.

Perfusion parameters for lungs from all pigs including the background

GalTKO.hCD46 genotype, segregated by lung failure within four hours versus lungs surviving at four hours. X axis represents perfusion time in minutes. #: P < 0.05, *: P < 0.005

Discussion

Using an extensive dataset derived from a mechanistically informative preclinical model of pig-to-human lung transplantation, this novel meta-analysis supports important hypotheses about the multifaceted nature of lung xenograft injury by demonstrating cumulative effects associated with sequential addition of rationally targeted genetic modifications. This global view of the performance of multi-transgenic lungs demonstrated that an number of modifications was associated with improved lung protection despite general failure to prevent platelet and neutrophil sequestration. However, improved survival correlated with other markers of reduced thrombotic injury, supporting a critical role for coagulation pathway dysregulation in lung xenograft injury.

One possible conclusion that might be inferred from our analysis is that those genes that we find are associated with improved lung survival should be included in a new “standard” pig lung donor phenotype, as the reference for evaluating the influence of added additional genes. The current analysis supports the hypothesis that each of these modifications are independently beneficial, and it is plausible that each confers mechanism-specific protection, alone or in the context of a variety of other genotypes. However, this hypothesis can only be explored in the context of a much more granular assessment of gene expression in individual animals, measured in association with particular promoters, and by correlating the effect of each transgene with mechanism-specific biochemical or histologic markers for each pathway. This level of detail is not accessible in this “meta-analysis”, which surveys a very heterogeneous study population that includes small numbers of multiple different multi-gene phenotypes. In addition, going forward, as we evaluate pigs with 6 or more genetic modifications, we anticipate there will be synergistic effects of specific transgene combinations that may only demonstrate efficacy (ie. long-term survival) in specific combinations, and that threshold or dose-dependent effects will correlate with levels of gene expression. As such, efficacy may not necessarily be predicted by analysis of 2-gene or 3-gene pig lungs. Based on our recent report which takes this granular analytic approach, 12 we consider the GalTKO.hCD46 as our genetic “platform” for an eventual clinical lung xenotransplant application.

In this model, expression of hTBM and HLA-E had no significant survival effect, while CD39 appeared to be associated with shorter lung survival. In contrast to our findings, hCD39 expression was associated with a protective effect in the context of multimodal complement control in xenoperfused GalTKO.hCD55.hCD59 lungs as reported by Westall et al. 14 This discrepancy may be due to heterogenous expression in our hCD39 transgenic pigs (unpublished observations), as might be expected for founder animals that were not pre-selected for high expression levels. Similarly, the absence of a salutary effect associated with hCD39 and HLA-E may be due to low endothelial protein expression in some or all of the pigs tested. For hTBM, all animals were pre-selected for high-level, endothelium-specific expression of the transgene. It is possible that the heparinization required for maintaining blood flow in this ex vivo model was sufficient to mask or overwhelm the activation of protein C by overexpression of the hTBM transgene. For those pig lungs derived from founder animals (CD39, EPCR, HO1, as well as, pigs with more than 3 modifications), it will be important to follow up with evaluation taking into account transgene expression in the lung.

Currently, efforts are in progress to quantify lung expression for each of the transgenes discussed here; those detailed expression analyses and associated biochemical and histologic observations are beyond the scope of this exploratory “meta-analysis”. In summary, before concluding that the new “platform lung” should be GalTKO.hCD46.hCD55.hEPCR, for example, we believe that detailed mechanism-specific analyses are required before considering any particular gene “important” or “essential” to progress toward the clinic, or excluding others.

We were surprised that hTBM was not associated with improved lung xenograft survival, since thrombin elaboration is closely associated with lung failure in our previous studies. We hypothesize that, because pEPCR is a poor catalyst for activation of human protein C, and aPC is essential to amplify the anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory properties that might be expected in association with transgenic hTBM expression, co-expression of hTBM and hEPCR may be required to optimize activation of human protein C. Such co-expression may unveil the therapeutic potential we expect in association with this phenotype. 30,31 In addition, the levels of heparin required for this ex vivo lung model could mask the potentially protective effects of hTBM expression. This theoretical analysis illustrates the limitations of a “meta-analysis” approach, and reinforces the need to specifically challenge each of our observations at a mechanistic level with appropriate reference groups and informative assays.

Despite improved survival that is generally associated with increasing numbers of genetic modifications, neutrophil and platelet sequestration, and elaboration of thrombin (F1+2), histamine (not shown), and thromboxane remain prolific. Our working hypothesis is that residual adhesive, thrombogenic, and inflammatory mechanisms remain sufficient to mediate physiologically important lung xenograft injury. The trigger(s) for residual injury remain an active focus of our current studies. Parallel pilot in vivo studies (unpublished observations) confirm the predictive value of the ex vivo model, and support our hypothesis that mechanisms not regulated by the genetic alterations tested to date will need to be controlled in order to enable long-term life-supporting in-vivo lung xenograft survival. Identifying these pathways as refractory to control by the genetic modifications tested to date is helping us prioritize important targets for additional genetic or pharmacologic interventions. An important limitation of this survey analysis is that the location and amount of transgene expression are not considered, as logically pivotal confounding variables. Consistently robust transgenic hCD46 and hTBM expression has been validated and reported for the pig founder lines reported here. 10,32 In contrast, as noted above, hCD39 expression has been highly variable between the relatively small number of animals we have studied. Further, although founder hEPCR expression was high, relative to expression on human cells, endothelial and pulmonary hEPCR expression remains to be evaluated for lungs of animals included in this series. In addition, while this analysis evaluates the global effects of individual genes across a variety of contexts, it does not account for interactions between genes that could potentially prove very important (eg, hTBM and hEPCR, as discussed above). While the ex-vivo xenoperfusion model is mechanistically informative and clinically relevant, 1,25 it does not enable evaluation of lung injury and performance beyond the acute reperfusion interval, nor in the absence of added heparin in the circuit. Finally, as the purpose of this study was to analyze the independent effects of genetic interventions, this did not include experiments using additional drugs and other interventions – which play an important role in advancing our understanding lung xenograft injury at a mechanistic level, but are beyond the scope of the current report. 1 Our findings for each gene, and for each drug added to the system, will require detailed examination of mechanism-specific effects, and in the context of gene expression in physiologically relevant locations in the lung, to formally test the hypothesis that any particular modifications to further “humanize” the xenograft are beneficial, or ineffective, or deleterious. The high-throughput, “canary-in-the-coal-mine” lung perfusion model should facilitate definition of the cassette of human transgenes, and drugs, that will be required in order to optimize control of the various diverse pathogenic pathways that contribute to lung xenograft injury. 1

Conclusion

This meta-analysis of an extensive lung xenotransplantation series analyzes the effects on xenograft survival associated with a variety of genetic modifications of pig donors. Importantly, we find that the modifications studied are generally associated with increases in lung survival, and the protective effect generally increases with the number of genes expressed. While not all genetic interventions were associated with lung survival prolongation in this survey analysis, this study supports the general strategy of using multimodal genetic modifications to target critical mechanisms of xenograft injury.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Donald G. Harris: NIH NHLBI T32 HL 007698

Siamak Dahi: NIH NHLBI T32 HL 072751

Richard N. Pierson: NIH NIAID UO1 AI 66335U & 01 AI 066719; Sponsored Research

Agreement with Revivicor, Inc; and unrestricted gift support from United Therapeutics, Inc. to the University of Maryland, Baltimore Foundation.

Laurence Magder of the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Epidemiology & Public Health reviewed the statistical methods. Special thanks to all current and former members of the team who participated in these experiments, including but not limited to Tianshu Zhang, Bao Nguyen, Sean Kelishadi, Tiffany Stoddard, Yuming Zhao, and Andrea Riner. Additional thanks Simon Robson, Peter Cowan, Eckhard Wolf, Nikolai Klymuik, and the staffs at Revivicor, United Therapeutics, and Ludwig Maximilians University for extensive contributions to the genetic advances entailed in these studies.

ABBREVIATIONS

- aPC

Activated protein C

- CD62p

P-selectin

- F1+2

Prothrombin fragments 1 & 2

- Gal

Galactose 1,3α-galactose

- GalTKO

α-1,3 galactosyl transferase gene knockout

- hCD39

Human ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1

- hCD46

Human membrane cofactor protein

- hCD55

Human complement decay-accelerating factor

- hCD59

Human membrane attack complex inhibitory protein

- hEPCR

Human endothelial protein C receptor

- hHO-1

Human hemoxygenase 1

- hTBM

Human thrombomodulin

- HLA-E

Human human leukocyte antigen alpha chain E

- IQR

Interquartile range

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

Disclosures:

RNP serves without compensation on Revivicor’s Scientific Advisory Board, and CJP and DLA are employees of Revivicor, Inc. Revivicor, Inc. is a wholly owned subsidiary of United Therapeutics, Inc. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions.

Concept and design: DGH, KJQ, SD, LB, RNP. Data collection: DGH, ES, EK, LB, AMA. Critical scientific contributions: CJP, DLA, LB, AMA, RNP. Data analysis and interpretation: DGH, KJQ, ES, EK, CJP, DLA, LB, AMA, RNP. Statistics: DGH, ES, EK. Drafting article: DGH, KJQ, BMF. Critical revision: SD, CJP, DLA, LB, AMA, RNP. Approval of article: CJP, DLA, LB, AMA, RNP.

References

- 1.HARRIS DG, QUINN KJ, DAHI S, et al. Lung xenotransplantation: recent progress and current status. Xenotransplantation. 2014 doi: 10.1111/xen.12116. [contains unpublished results] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COOPER D, KEOGH A, BRINK J, et al. Report of the xenotransplantation advisory committee of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: the present status of xenotransplantation and its potential role in the treatment of end-stage cardiac and pulmonary diseases. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000;19:1125–1165. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EKSER B, EZZELARAB M, HARA H, et al. Clinical xenotransplantation: the next medical revolution? Lancet. 2012;379:672–683. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61091-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.COZZI E, VIAL C, OSTLIE D, et al. Maintenance triple immunosuppression with cyclosporin A, mycophenolate sodium and steroids allows prolonged survival of primate recipients of hDAF porcine renal xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:300–310. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.YAMADA K, YAZAWA K, SHIMIZU A, et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of α1, 3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2004;11:32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MOHIUDDIN M, SINGH A, CORCORAN P, et al. One Year Heterotopic Cardiac Xenograft Survival in a Pig to Baboon Model. Am J Transpl. 2014;2:488–489. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.BOTTINO R, WIKSTROM M, VAN DER WINDT D, et al. Pig-to-Monkey Islet Xenotransplantation Using Multi-Transgenic Pigs. Am J Transpl. 2014;14:2275–2287. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MOHIUDDIN M, SINGH A, CORCORAN P, et al. Genetically Engineered Pigs And Target Specific Immunomodulation Provide Significant Graft Survival And Hope For Clinical Cardiac Xenotransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1106–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PHELPS CJ, KOIKE C, VAUGHT TD, et al. Production of α1, 3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LOVELAND BE, MILLAND J, KYRIAKOU P, et al. Characterization of a CD46 transgenic pig and protection of transgenic kidneys against hyperacute rejection in non-immunosuppressed baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3089.2003.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GALILI U. The α-gal epitope (Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc-R) in xenotransplantation. Biochimie. 2001;83:557–563. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BURDORF L, STODDARD T, ZHANG T, et al. Expression of human CD46 modulates inflammation associated with galtko lung xenograft injury. Am J Transpl. 2014;14:1084–1095. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.YEATMAN M, DAGGETT CW, PARKER W, et al. Complement-mediated pulmonary xenograft injury: studies in swine-to-primate orthotopic single lung transplant models. Transplantation. 1998;65:1084–1093. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WESTALL GP, LEVVEY BJ, SALVARIS E, et al. Sustained function of genetically modified porcine lungs in an ex vivo model of pulmonary xenotransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WIEBE K, POELING J, MELISS R, et al. Improved function of transgenic pig lungs in ex vivo lung perfusion with human blood. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:773–774. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SCHRÖDER C, PFEIFFER S, WU G, et al. Effect of complement fragment 1 esterase inhibition on survival of human decay-accelerating factor pig lungs perfused with human blood. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(03)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.KULICK DM, SALERNO CT, DALMASSO AP, et al. Transgenic swine lungs expressing human CD59 are protected from injury in a pig-to-human model of xenotransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:690–699. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DAGGETT CW, YEATMAN M, LODGE AJ, et al. Swine lungs expressing human complement–regulatory proteins are protected against acute pulmonary dysfunction in a human plasma perfusion model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:390–398. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.COOPER DK, EKSER B, BURLAK C, et al. Clinical lung xenotransplantation–what donor genetic modifications may be necessary? Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:144–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2012.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CANTU E, BALSARA K, LI B, et al. Prolonged Function of Macrophage, von Willebrand Factor-Deficient Porcine Pulmonary Xenografts. Am J Transpl. 2007;7:66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CANTU E, GACA JG, PALESTRANT D, et al. Depletion of pulmonary intravascular macrophages prevents hyperacute pulmonary xenograft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2006;81:1157–1164. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000169758.57679.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BUDORF L, RYBAK E, ZHANG T, et al. Human EPCR expression in GalTKO.hCD46 lungs extends survival time and lowers PVR in a xenogenic lung perfusion model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:S137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.BURDORF L, ZHANG T, RYBAK E, et al. Combined GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa blockade prevents sequestration of platelets in a pig-to-human lung perfusion model. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:287–287. [Google Scholar]

- 24.BURDORF L, RYBAK E, ZHANG T, et al. Combined thromboxane synthase inhibition and H2-receptor blockade prevents PVR elevation during GalTKO.hCD46.hCD55 pig lung perfusion with human blood. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:S257–S258. [Google Scholar]

- 25.BURDORF L, AZIMZADEH AM, PIERSON RN. Xenogeneic lung transplantation models. In: COSTA C, MANEZ R, editors. Xenotransplantation. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 169–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NGUYEN BH, AZIMZADEH AM, SCHROEDER C, et al. Absence of Gal epitope prolongs survival of swine lungs in an ex vivo model of hyperacute rejection. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:94–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.PFEIFFER S, ZORN GL, III, BLAIR KS, et al. Hyperacute lung rejection in the pig-to-human model 4: evidence for complement and antibody independent mechanisms. Transplantation. 2005;79:662–671. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000148922.32358.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WUENSCH A, BAEHR A, BONGONI AK, et al. Endothelial-specific expression of biological active human thrombomodulin in single-transgenic pigs and pigs with multiple genetic modifications. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:346. [Google Scholar]

- 29.AZIMZADEH A, ZORN G, BLAIR K, et al. Hyperacute lung rejection in the pig-to-human model. 2. Synergy between soluble and membrane complement inhibition. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:120–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SALVARIS E, FISICARO N, MORAN C, COWAN P. In vitro assessment of the compatibility of thrombomodulin and endothelial protein C receptor in the pig-to-human setting. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:345–345. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ROUSSEL J, MORAN C, SALVARIS E, et al. Pig thrombomodulin binds human thrombin but is a poor cofactor for activation of human protein C and TAFI. Am J Transpl. 2008;8:1101–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SIEVERT E, CHENG X, GAO Z, et al. Detecting the presence of hTM in lung tissue of GalTKO.hCD46.hTM transgenic pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:380. [Google Scholar]