Abstract

The advanced electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) techniques, electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) and electron spin echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) spectroscopies, provide unique insights into the structure, coordination chemistry, and biochemical mechanism of Nature’s widely distributed iron-sulfur cluster (FeS) proteins. This review describes the ENDOR and ESEEM techniques and then provides a series of case studies on their application to a wide variety of FeS proteins including ferredoxins, nitrogenase, and radical SAM enzymes.

Introduction

Iron-sulfur proteins share an important history with paramagnetic resonance techniques. Indeed, FeS proteins were first identified by Helmut Beinert with the use of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. [1, 2] [3, 4] This review will assume some familiarity with the basics of EPR, and will thus focus on the advanced EPR techniques, electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) and electron spin echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) spectroscopies, and their contributions towards extending our understanding of the roles played by FeS proteins. These spectroscopic techniques were invented roughly concurrently with the discovery of FeS proteins (i.e., late 1950’s – early 1960’s), [3–6] and ENDOR was applied to two-iron ferredoxins (2Fe-Fds) not long thereafter. [7, 8]

This review first provides an overview of the multiple forms in which ENDOR and ESEEM spectroscopies are currently practiced, and then describes in detail specific cases where these techniques have yielded important insights into the structure and biochemical action of iron-sulfur proteins. The emphasis is on more recent work; however, as appropriate we will detail studies that, beginning in the 1980’s, initiated the application of these techniques to FeS proteins, and that provide the foundation for recent studies.

The techniques of ENDOR and ESEEM spectroscopy aid in the understanding of various characteristics of metal ions and FeS clusters in biology such as: electronic and magnetic properties, enzyme mechanism, structure (coordination geometry, valence, and ligand identification with or without substrate/product/inhibitors) and protein dynamics. EPR spectra of metalloproteins are often too broad to resolve the interactions that contain the desired biochemical and physical information. In these cases, ENDOR and ESEEM spectroscopies provide this information at significantly higher resolution than from EPR alone.

The interactions of a metalloprotein’s unpaired electron spin(s) (S) and a nuclear spin (I), are measured by their hyperfine couplings, denoted A. A large number of biochemically relevant nuclei have non-zero nuclear spin (I > 0) with examples arising from amino acid residues, cofactors, or substrates/inhibitors including naturally abundant isotopes such as: 1H, 14N, 19F, 31P, and those requiring isotopic enrichment such as: 2H (D), 13C, 15N, 17O, and 33S. Many metallic elements have non-zero spin isotopes of which 57Fe (I = 1/2, 2.2% abundance) is the most relevant here. For larger hyperfine couplings, or interactions where the intrinsic linewidth of the EPR spectrum is narrow, these electron-nuclear interactions can be directly observed in the EPR spectrum. An example is the observation of hyperfine coupling from 63,65Cu (I = 3/2, together 100% abundance) in Type II copper centers, and even in this case, the coupling is resolved only in the g‖ region. More often than not, and in particular in the case of iron-sulfur proteins, the EPR linewidth of metalloprotein centers is sufficiently broad that small but important electron-nuclear hyperfine couplings are unresolved. To determine these hyperfine couplings and identify the nuclei of origin requires ENDOR and ESEEM spectroscopies, which will be described in the next section. The hyperfine information gained may identify nuclei within the coordination sphere, characterize bonding structure, determine bond order, and estimate electron-nuclear spin distances. These complementary advanced EPR techniques each are capable of resolving hyperfine couplings; whereas ENDOR spectroscopy is able to detect a wide a range of hyperfine couplings, from as little as ~10−1 MHz up to > 102 MHz, ESEEM techniques are typically limited to smaller hyperfine values, A < 10 MHz. Each technique can identify the nuclei present with ENDOR having the advantage of being broad-banded, but ESEEM spectroscopy has the advantage of being able to ‘count’ the number of equivalent nuclei (as in NMR).

Techniques

EPR

The electronic paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum provides the first information associated with the Fe-S center: its electronic spin state (S ≥ 1/2, with S = 1/2 and 3/2 being the most amenable to study), iron d orbital configuration, FeS cluster oxidation state, and general molecular framework of the FeS cluster is established, and described in more detail elsewhere. [9–11] This information arises from the associated electron energy levels and their interaction with an externally applied magnetic field. In recording an EPR spectrum, the magnetic field, B, is swept while a microwave field of fixed energy (E = hν; ν = frequency; typically ~9 GHz (X-band) or 35 GHz (Q-band)), is applied, and resonant transitions occur at field positions characteristic to the electronic structure, which are described in terms of a g tensor (or matrix). In general, the three components of the g tensor (typically, gx, gy, gz, or, if one is reluctant to choose a geometrical designation, g1, g2, g3, or gmin, gmid, gmax) depend on the electronic structure, electron spin interactions, and the relative orientation of the molecule within the magnetic field. The individual g values that make up the g tensor may be viewed as deviations of the unpaired electron(s) from that of a ‘true’ free electron without any other interactions, which is ge = 2.00232…. These deviations result from the orbital aspects of the unpaired electron(s), which interact with the spin aspects of the electron. As the number of electrons in the paramagnetic center increases, these spin-orbital interactions increase, and are thus more significant for Fe-S clusters (i.e., paramagnetic 3d ions) than for, say, organic radical species (paramagnetic 2s, 2p molecules).

ENDOR

The paramagnetic centers of Fe-S clusters in Nature create unique spectroscopic probes for both electronic and structural coordination characterization by EPR (discussed in detail elsewhere in this special issue) and electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectroscopies. [4, 12–16] In principle, any system with non-zero electron spin, S > 0, not only Kramers (S half-integer) but also non-Kramers states (S integer), can be EPR active and give advanced paramagnetic resonance responses. However, we focus here on what is perhaps the most common spin state in FeS proteins, and which is by far the most amenable to study by EPR and advanced techniques, namely S = 1/2. This unpaired electron spin of the Fe-S center paired with either its own iron nuclear spin(s), with spins of nuclei within the coordination sphere and of substrates/products/inhibitors allow one to generate a wealth of information for the Fe-S center. First, the electronic information of the iron ions may be determined through ENDOR hyperfine measurements of the 57Fe nuclei. [17–20] This sole magnetically active isotope of iron is present in only 2.15% natural abundance, and thus, isotopic enrichment in 57Fe is usually desirable. [1, 2] Secondly, one may answer the question of what atoms, either through natural abundance or isotopic labeling, are within the first and second coordination sphere of the Fe-S cluster. These include isotopes such as 1H, 13C, 15N, 19F, 31P, 57Fe (all I = 1/2), 2H, 14N (both I = 1), 33S (I = 3/2), and 17O, 95,97Mo (all I = 5/2).

While the EPR spectrum provides us with much preliminary information, including an orientation frame with which to view our molecule, much of the information desired, namely the electron-nuclear hyperfine and quadrupole interactions are small in energy and thus unresolved within the broad linewidth of the FeS cluster’s EPR spectrum. ENDOR spectroscopy, by virtue of the higher resolution and lower energy scale of the NMR experiment, directly measures these interactions governed by the nuclear spin Hamiltonian, HN:

| (1) |

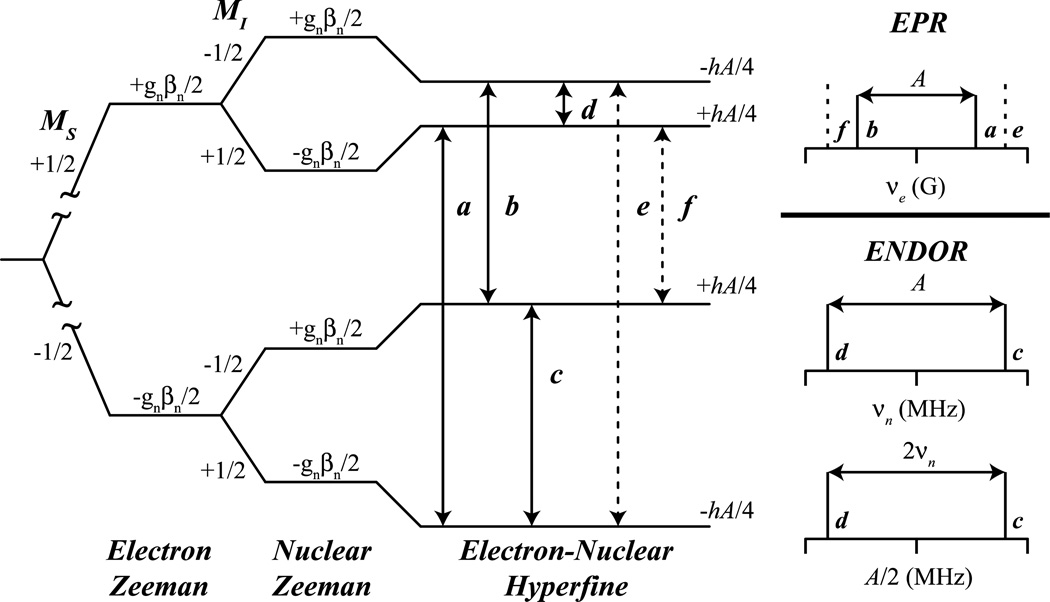

where βN is the Bohr magneton, which is a constant for all nuclei, gN is the nuclear g value, unique to each isotope, I is the isotope’s nuclear spin, and B is the magnetic field. The orientation dependent hyperfine interaction, A, depends on the electronic spin, S, and the nuclear spin of the isotope being measured, I. For a given S, the quantized spin angular momentum levels are: MS = [−S, (−S +1), …, 0, …, (S − 1), S], with an analogous situation for I (MI = [−I, (−I +1), …, 0, …, (I − 1), I]. Allowed EPR transitions involve a change in electronic spin level: ΔMS = ±1, ΔMI = 0, while ENDOR (i.e., NMR) transitions are: ΔMS = 0, ΔMI = ±1. Figure 1 outlines the allowed EPR and ENDOR transitions of an S = 1/2, I = 1/2 system, where solid lines a and b satisfy the ΔMS = ±1, ΔMI = 0 selection rule for EPR, while solid lines c and d satisfy the selection rules ΔMS = 0, ΔMI = ±1 for ENDOR spectroscopy. Lines e and f are ΔMS = ± 1, ΔMI = 1 forbidden EPR transitions.

Figure 1.

Energy level diagram derived from the nuclear spin Hamiltonian (Eq 1) for a S = 1/2, I = 1/2 system. Solid lines represent allowed EPR (a, b) and ENDOR/ESEEM (c, d) transitions and dashed lines represent forbidden EPR (e, f) transitions. The stick representations (right) display the transition observed for EPR spectra (top) and for ENDOR spectra in ‘weak’ νn centered (middle) and ‘strong’ A/2 centered (bottom) coupling patterns.

ENDOR spectra are collected at static magnetic fields, each field defining a single EPR resonance among all possible, fixing the nuclear Zeeman portion of the nuclear Hamiltonian. Nuclei at this fixed magnetic field will resonate at a Larmor frequency, νN, determined by: hνN = gNβNB, which scales with magnetic field, B. An unpaired electron spin creates an large internal field that perturbs any nearby magnetically active nuclear spins, much like the significantly smaller internal field interactions between nuclear spins created in traditional NMR experiments measured by their chemical shift. Just as a 500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum measures the deviation of protons from their Larmor frequency, νN (1H) = 500 MHz, at a magnetic field of 120 kG (12 T), ENDOR will measure proton interactions with large electronic spins which increases the internal magnetic field felt by the surrounding nuclear spins. [16] For ENDOR, this internal field is measured as a hyperfine coupling interaction tensor, A. The observed ENDOR transitions may appear as Larmor centered, νN, split by the hyperfine coupling, A, when the internal field is smaller than the external field: νN > A/2 – or – when the internal field is larger than external field νN < A/2, the transitions with appear centered at half of the hyperfine coupling and split by 2νN. These two possibilities are given by the following (first-order) equation:

| (2) |

The right panel of Figure 1 explores the ‘weak’ Larmor-centered and ‘strong’ A/2-centered hyperfine coupling patterns for an S = 1/2, I = 1/2 spin system – the simplest ENDOR active spin system.

The hyperfine coupling (hfc), A, interaction for a particular nucleus contains a wealth of information. This is because hfc is related to electron spin delocalization onto a given nucleus, and hence, bonding information, geometry, and structural information. The matrix, A, can thus be decomposed into two components: A = Aloc + T. The first component, Aloc, is the local contribution to the observed hyperfine coupling and it depends on the nuclear properties of the nucleus observed. Various interactions of this nucleus with the electron spin are ‘contained’ within Aloc, including covalent bonding interactions and isotropic hyperfine coupling arising in general from electron spin density in s-orbitals at the nucleus. Ideally, the collection of Aloc of all nuclei for a metallocenter yields a complete composition of the covalent bonding network electron spin in the first coordination sphere. For the atoms involved in the ‘covalent’ bonded network, in-depth analysis of Aloc can yield rich inorganic information, such as: i) valency of the metal ions, [21] ii) covalency of the ligands [22] and iii) the coordination geometry of the metallocenter. The second term, T, garners the non-local, dipolar coupling information of atoms near the metallocenter, covalently bonded or not. Dipolar couplings allow for distance estimates between the nuclear and electron spin, and other geometric constraints such as angles and coordinates. [14, 23]

Atoms of nuclear spin I ≥ 1 possess a non-spherical atomic nucleus and are referred to as quadrupolar nuclei. In contrast to nuclei with I = 1/2, for which the MI = ±1/2 values are equal in energy (degenerate) in the absence of an external magnetic field, regardless of their electronic environment, nuclei with, e.g., I = 1 (as in 14N) have MI = 0, ±1 levels, which may have differing nuclear energy magnitudes, even in the absence of external magnetic field. [9] All that is required is an internal electric field gradient, which can result from an unequal charge distribution around the quadrupolar nucleus, which could be the consequence of an imbalance of p orbital valence electrons about the nucleus. [24] This ‘charge distribution’ is measured and observed as an additional splitting of the ENDOR transitions described above. In this case of quadrupolar splitting, denoted as P (or sometimes Q), each ENDOR peak is further split by the quadrupole moment into 2I lines dictated by the following (first-order) equation:

| (3) |

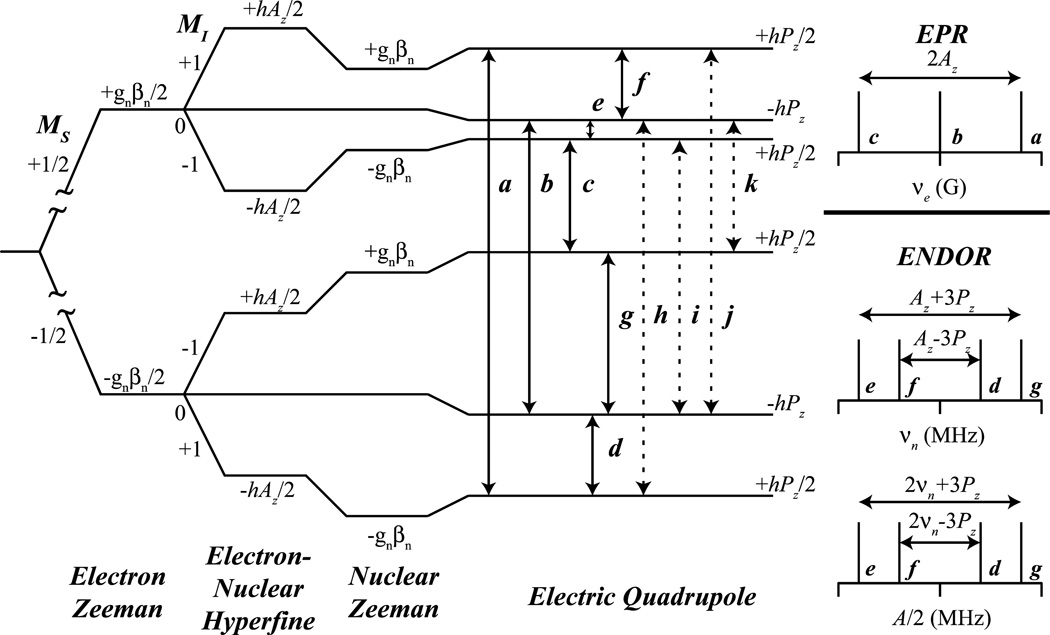

applicable when the quadrupole splitting is much smaller than the hyperfine. [9] For an S = 1/2, I = 1 system, the same ENDOR selection rules, ΔMS = 0, ΔMI = ±1, still apply, however, the possible splitting pattern is now more complex, as seen in Figure 2. For an axial quadrupole tensor, P = [−Px/2, −Py/2, Pz], the allowed ENDOR transitions are as follows: e and f of the MS = +1/2 manifold, and d and g of the MS = −1/2 manifold. The hyperfine can once again be in a ‘weak’ or ‘strong’ coupling regime as described earlier, however, for each, the observed quadrupole splitting is the same, 3P, Figure 2. The quadrupole coupling information thus obtained can be extremely powerful in determining bonding information and bond order, critical for distinguishing e.g., sp2 imidazole nitrogens from other protein nitrogenous species. [24, 25]

Figure 2.

Energy level diagram derived from the nuclear spin Hamiltonian (Eq. 1) for a S = 1/2, I = 1 system with an axial quadrupole tensor along the z axis. Solid lines represent allowed EPR (a, b, c) and ENDOR/ESEEM (d, e, f, g) and dashed lines represent semi-forbidden ESEEM (h, i, j, k) transitions.

Many of the Fe-S protein samples studied by EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy are in a frozen solution and therefore are a random distribution of all possible orientations in the magnetic or lab frame, hence the probability distribution of the field to align with any given orientation is equivalent. As each of the hyperfine, A, and quadrupole, P, tensors are orientation dependent, the deconvolution and mapping of complete tensors onto the electronic g tensor is performed through analysis of 2D field-frequency ENDOR spectra. [16, 26–29] ENDOR spectra collected at the magnetic field edges of the rhombic EPR spectrum typically resemble a ‘single-crystal-like’ position, therefore one is observing only a single map of the A and P tensors along a single axis of the g tensor. ENDOR spectra of the 2D field-frequency between these field edges represent a mathematical subset of orientations of hyperfine and quadrupole. Through the correspondence of magnetic field (g values) and angular section, the absolute values and orientations of each A and P may be mapped onto the relative molecular frame provided by the g tensor.

ENDOR spectra may be collected with ‘continuous-wave’ (CW) microwave instrumentation by holding the magnetic field static while sweeping an applied radiofrequency (RF). The classic CW method for ENDOR acquisition involves field modulation and phase-sensitive detection with an RF sweep, and has superior sensitivity to the currently more popular pulsed ENDOR techniques. [14] However, pulsed ENDOR techniques frequently are able to give better-resolved ENDOR line shapes, and to resolve weaker hyperfine couplings. [30, 31]

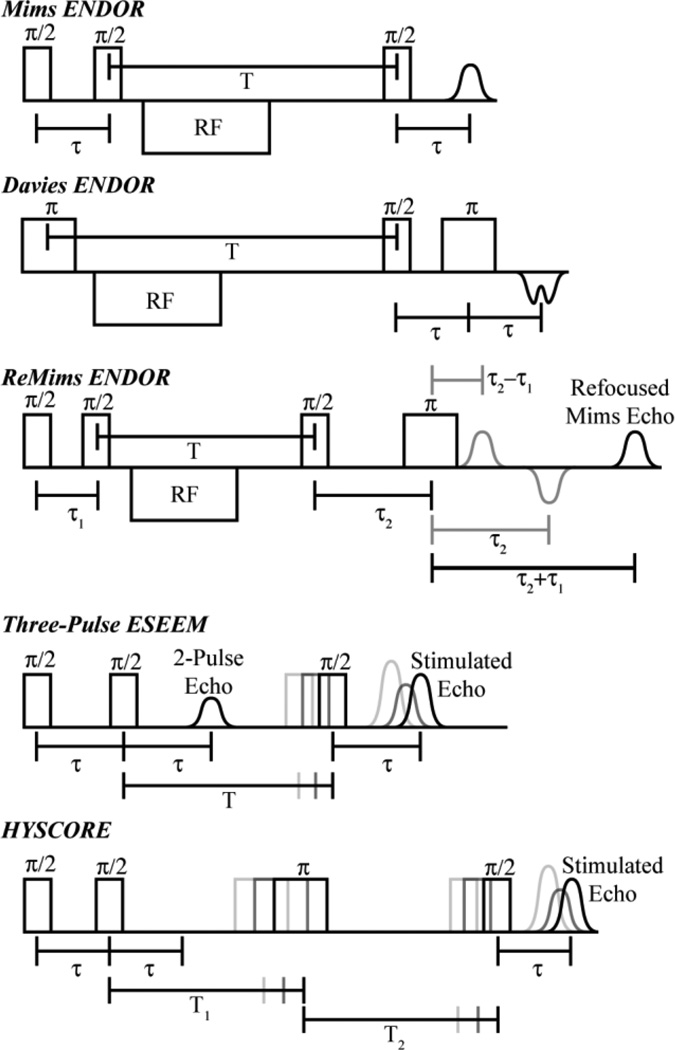

Pulsed ENDOR techniques consist of microwave pulse sequences with the incorporation of RF pulses. There are two fundamental pulsed ENDOR techniques, named after their inventors, Mims [6] and Davies, [32] respectively. The Mims ENDOR pulse sequence is based on the three-pulse (each 90° pulse is represented by π/2 in the sequence) stimulated electron spin echo (ESE) sequence: π/2 −τ − π/2 − T − π/2 − τ − echo (Figure 3). To achieve ENDOR, an RF pulse is applied during time T. The Mims sequence can be used for large couplings but is most useful for resolving small hyperfine couplings, generally less than 4 MHz. Its sensitivity is a joint function of the hyperfine coupling being interrogated, A, and the interval, τ.

| (4) |

The Mims ENDOR sequence thus is affected by ‘blind spots’ (i.e., points at which the S/N is essentially zero), when A = n/τ, where n = 0, 1, …, integer. [33]

Figure 3.

Schematic representations of the Mims, Davies, and ReMims ENDOR pulse sequences, the three pulse ESEEM sequence, and the Hyperfine Sublevel Correlation (HYSCORE) pulse sequence.

The presence of blind spots can sometimes be advantageous as they can allow suppression of signals with specific hyperfine coupling, potentially simplifying spectra. [33] The first two ‘non-selective’ microwave pulses of the stimulated pulse sequence are responsible for the holes created in Mims ENDOR as the π/2 − τ − π/2 sequence creates a ‘polarization grating’ within the inhomogeneous EPR line where the ENDOR is detected. [34]

For larger hyperfine couplings, generally greater than 4 MHz, the Davies ENDOR sequence, π − T − π/2 − τ − π − τ − echo, where the RF is applied once again at time T, is employed (Figure 3). [32] The preparation microwave π pulse is first applied to ‘flip’ the electron spin and then the RF pulse is applied during time T to then excite and mix nuclear transitions that match the RF pulse frequency. A Hahn echo sequence (i.e., the originally invented ESE sequence; described in more detail in the ESEEM section below): π/2 − τ − π − τ − echo, is then applied and directly detects the NMR polarization of the EPR transition created by the RF pulse, yielding the ENDOR measurement. In contrast to the Mims pulse sequence; the Davies ENDOR detection is described by the function, [33, 35]

| (5) |

where tp is the separation in time between the first two pulse. For the Davies ENDOR response, the ‘hole in the middle,’ appears as A goes to zero, but otherwise the ENDOR response does not have ‘blind spots’.

These two pulse sequences have set the foundation for development of additional techniques. The Remote-Echo Mims (ReMims) ‘four-pulse’ sequence (Figure 3) developed by Doan allows for the collection of distortion-free ENDOR spectra of nuclei with hyperfine coupling greater than typically obtainable by the Mims pulse sequence, and is useful to bridge the gap in hyperfine coupling between traditional Mims and Davies ENDOR methods. [36]

Another pulsed ENDOR ‘trick’ for deconvolution of ENDOR spectra and to ease the process of assignments of overlapping peaks is the employment of TRIPLE spectroscopy (where TRIPLE is not an acronym for anything and is sometimes referred to as double ENDOR). [34, 37] As it is considered a ‘pump – probe’ technique, the TRIPLE technique may be able to resolve and confirm nuclei hyperfine coupling assignments. A second ‘pump’ RF pulse of a constant frequency is added before the variable ‘probe’ RF pulse of the ENDOR pulse sequence. When the pump frequency matches a ENDOR transition of a ν+ transition of a given nuclei, for example, the irradiation will cause an intensity change of the ν− transition, correlating the ν−/ν+ pair for a single hyperfine coupling.

Relative signs of a hyperfine tensor for individual nuclei can sometimes be found through the analysis and simulation of 2D field-frequency ENDOR patterns, when a through-space dipole interaction gives a reference sign (e.g. [38, 39]). Likewise TRIPLE can sometimes be used to determine relative hyperfine signs of multiple nuclei in a system through the so-called implicit TRIPLE effect. [40] First established on the low-spin FeIII (S = 1/2) center of the non-heme enzyme nitrile hydratase, [40] the implicit TRIPLE effect has been extended to FeS clusters. [41] Whereas the determination of relative 57Fe hyperfine coupling signs has been well established in ENDOR, recently multi-pulse sequences have been developed to obtain absolute sign information, starting with the work of Bennebroek and Schmidt. [42,43, 44] Most recently, a robust and reliable multi-pulse sequence has been developed by Doan, the Pulsed ENDOR Saturation Recovery (PESTRE) protocol, which determines absolute signs of hyperfine couplings in conjunction with corresponding ENDOR measurements, described below. [45, 46] No longer does the assignment of absolute signs of 57Fe hyperfine couplings of FeS clusters depend solely on high field Mössbauer measurements. [20]

ESEEM

Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation Spectroscopy (ESEEM) [47–49] is a microwave-only pulsed technique that has the ability to resolve small hyperfine and quadrupole couplings that may not be resolved using other advanced techniques such as ENDOR spectroscopy, and has the experimental advantage of simplicity as no separate RF equipment is required, unlike for ENDOR. [50] ESEEM, as the name implies, employs the detection of a spin echo by a two pulse (primary echo), π/2 − τ − π − τ − echo, or a three pulse (stimulated echo) sequence, described later. The basic two pulse sequence, often employed for ‘electron-spin-echo-detected’ EPR spectra, will create what is also often referred to as a Hahn spin echo. [51] After the π/2 pulse flips electron spins into the orthogonal plane of the magnetic field vector, the electron spins dephase at a relaxation rate, T1e, characteristic of the electron spin system. For transition metal ions at temperatures below 10 K, typical T1e times are on the order of 10 µs. The electron spin is allowed to ‘dephase’ during a time τ before it is flipped again by π. The electron spin has memory and will begin to ‘rephase’ much like the previous ‘dephasing’ but now in the opposite axis direction so as to develop an echo which appears at the same time interval for the original dephasing, τ. By varying τ, the ‘dephasing’ behavior of the electron spin is detected.

As in ENDOR, the electron and nuclear Zeeman effects dominate the spectrum and will dominate the electron spin echo’s intensity. However, electron-nuclear hyperfine and quadrupole interactions also contribute to the echo intensity, and they are better exploited by varying τ over a series of applied pulse sequences. When τ is varied, the echo intensity of each pulse sequence of a given step in time, τ, is measured, forming a time-domain spectrum. Primarily, the phase memory of the system is observed as exponential decay of the echo intensity as τ increases. Of central interest, periodic modulation(s) of the electron spin echo by nuclear interactions appear within the time domain spectrum. This modulation created by nuclear hyperfine and/or quadrupole transitions is of central interest in the ESEEM experiment, therefore deeper modulation is desired for increased S/N. The relaxation decay of the echo is subtracted from the time domain spectrum followed by subsequent processing (windowing, zero filling, etc. – the same “tricks” as used in FT-NMR) before the final Fourier transform that yields a frequency domain spectrum for easier observation of the hyperfine and quadrupole couplings.

ESEEM spectroscopy has the advantage over ENDOR spectroscopy of being able to ‘count’ similar nuclei of similar hyperfine and quadrupole parameters by the nuclear modulation depth. [25] In contrast, ENDOR signal intensities are difficult to correlate with number of nuclei. For example, this quantitative ability of ESEEM has been extremely useful in the determining the number of imidazole ligands of a given metallocenter. [25]

The transitions observed in ESEEM vary slightly from those of ENDOR. As ENDOR spectroscopy follows its selection rules more rigorously, ESEEM techniques exploit both allowed and ‘semi-forbidden’ transitions. [34] For S = 1/2, I = 1/2 cases, maximum modulation depth within the ESEEM time-domain spectrum is obtained when the microwave energy ‘matches’ the Hamiltonian energy (Eq 1), taking into specific consideration the second and third terms, the hyperfine and quadrupole interactions, respectively. ESEEM transitions observed for I = 1/2 nuclei are a result of only the anisotropic portion of the hyperfine tensor (primarily T; see definition for A given above). Many anisotropic nuclei that may be of interest, e.g., 1H couplings of metal-bound 1HxO species, have very broad lines, so that the modulation is frequently lost within the dead time of the instrument, making ESEEM of I =1/2 systems often difficult. [50] However, 15N (I = 1/2) isotopic labeling can be useful for analyzing weaker 14N couplings, because the 15N ESEEM can yield a more direct estimate of the dipolar contribution, which can then be used in interpreting the 14N ESEEM data, which contain isotropic and quadrupole couplings, as discussed next.

For S = 1/2, I = 1 cases, frequently histidine 14N systems at X-band (~ 9.5 GHz), the quadrupole term now plays a significant role. [25] The off-diagonal matrix elements introduced by the rhombic quadrupole tensor allows for more significant mixing of the quantum states, and semi-forbidden ΔMI = ± 2, double quantum, transitions to occur, such as h, i, j, and k in Figure 2. The semi-forbidden transitions in Figure 2 are combination differences between the allowed EPR and ENDOR transitions, creating unique observable transitions for the ESEEM experiment. In the opposite view, when both allowed EPR and semi-forbidden ESEEM transitions are excited in the ESEEM experiment, their frequencies will beat against each other and result in single transitions at the ENDOR frequencies, for example i (EPR) – h (semi-forbidden) = f (ENDOR).

Three-pulse ESEEM, which has the sequence: π/2 − τ − π/2 − ΔT − π/2 − τ − echo (Figure 3), is often simpler to analyze as it contains only the principal ENDOR (NMR) frequencies and semi-forbidden transitions, while lacking the sum and difference peaks of transitions observed in a two-pulse ESEEM experiment. While greater signal intensity is achieved with the three-pulse ESEEM sequence as compared to the two-pulse ESEEM sequence for disordered (frozen solution) systems, the main disadvantage of three-pulse ESEEM is the inclusion of ‘blind-spots’ as a function of τ. These holes are caused by the same ‘polarization grating’, π/2 − τ − π/2, of the stimulated echo as seen in the Mims ENDOR spectroscopy, however, the hole pattern has no dependence on A, only on τ, therefore, multiple three pulse ESEEM spectra of varying τ should be collected to ensure proper assignments.

HYSCORE

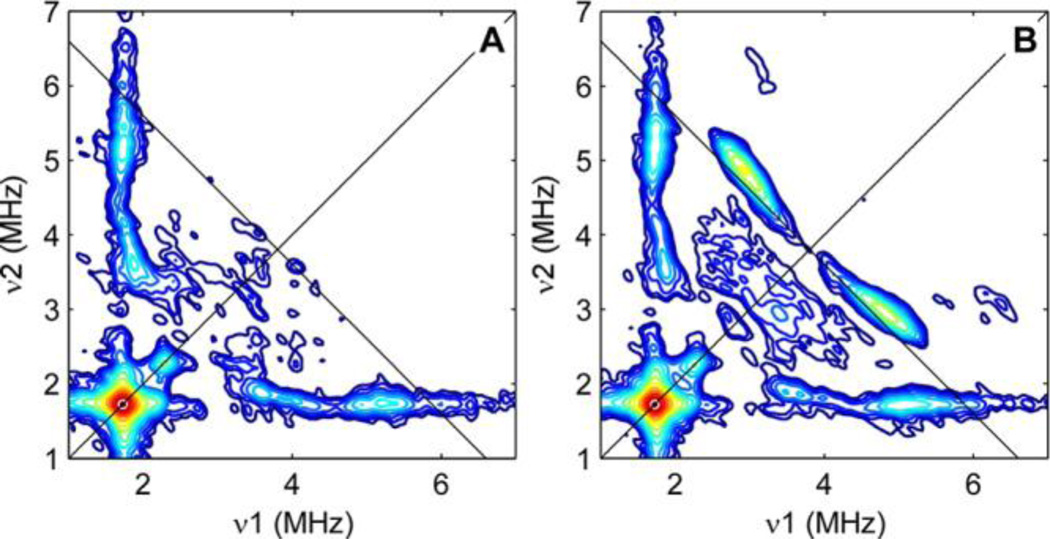

The development of three-pulse ESEEM techniques led to its extension into a two-dimensional form, [52] much as what had occurred earlier in NMR spectroscopy. This 2D ESEEM is referred to as hyperfine sublevel correlation (HYSCORE) spectroscopy, and is produced by the addition of a ‘mixing pulse’ to create a four-pulse ESEEM sequence. [53] While 3-pulse ESEEM works well for some disordered systems, it often loses much of the fast decaying modulation amplitude, quicker than the electron spin decay. This is much more of a problem for larger coupling with significant hyperfine anisotropy. The nuclear modulation is often lost before collection begins because of instrument dead time, or only a small amount is resolved before it decays. The addition of a fourth π pulse to the three pulse sequence alleviates this problem by transferring nuclear spin coherence from one manifold to the other and prolonging the modulation decay time. The addition of this π pulse between the second and third π/2 pulses of the three-pulse sequence, π/2 − τ − π/2 − T1 − π − T2 − π/2 − τ − echo (Figure 3), creates two separate ‘evolution’ periods before and after the π pulse, termed T1 and T2. The π pulse takes the nuclear coherence developed in the MS = ±1/2 electron manifold during the first evolution period and mixes it between the electron spin manifolds. The nuclear spin coherence now evolves in the MS = −/+ 1/2 electron spin manifold, and a nuclear coherence transfer echo is created at T1 = T2. The nuclear coherence transfer echo is most easily observed in the frequency domain spectrum along the diagonal of T1 = T2. The last π/2 pulse transfers the nuclear coherences to electron coherences for detection as an electron spin echo. The key aspect of the HYSCORE experiment is that the final electron spin echo produced has been modulated by the nuclear spins, similar to the ESEEM experiment, however, the mixing pulse helps extend the electron spin relaxation decay time, improving sensitivity relative to 2D three-pulse ESEEM spectroscopy of disordered (frozen solution) systems.

The typical four-pulse ESEEM experiment is done in a 2D fashion (HYSCORE) where T1 and T2 are incremented independently of each other and the final product therefore correlates the nuclear frequencies with the mixing of the electron spin manifolds. The 2D time domain spectrum is processed in a similar fashion as described earlier for ESEEM and 2D Fourier transform results in four quadrants, where, as with ENDOR, two coupling regimes are possible, either a strong (A > νn) or weak coupling (νn > A) regime; however, all peaks are not observed in a single quadrant. For ‘weak’ couplings of powder samples, peaks are once again Larmor centered perpendicular to the frequency diagonal in the first (+,+) and third (−,−) quadrants. For stronger couplings, cross peaks appear in the second and fourth quadrants, occasionally labeled as (+,−) and (−,+), respectively. This process allows for the readout and interpretation of multiple nuclei in a single spectrum that may have been unmanageable in a single ESEEM experiment. The powder pattern responses do not easily translate to complete hyperfine and quadrupole tensors. Complete line shape analysis and simulations at multiple magnetic field positions is the only true way to fully resolve A and P tensor values and their respective orientation to g, reviewed extensively elsewhere. [50, 54–57]

HYSCORE is most useful to resolve broad hyperfine lines that three-pulse ESEEM often fails to detect. The ability of HYSCORE to detect large anisotropic couplings of I = 1/2 nuclei such as 1H and 13C is a result of the added π mixing pulse, as these couplings are no longer lost through destructive interference which occurs in the three pulse experiment. Of course, HYSCORE still retains ‘blind-spots’ with τ time dependencies; therefore careful experimental and/or simulation considerations must be made.

Advanced EPR techniques applied to non-Kramers (integer-spin) systems

The above description of ENDOR, ESEEM, and HYSCORE techniques uses as examples the Kramers, S = 1/2, state the most common and spectrally rewarding of the possible spin states of FeS clusters. However, FeS clusters can also be found in higher spin states. Resting state nitrogenase has S = 3/2, and has been extensively studied by ENDOR as described elsewhere in this review and in other reviews. [58–60] For completeness it is useful to note that ENDOR and ESEEM can be productively applied to favorable integer spin states, primarily S ≥ 2, which can be found in 3Fe-red clusters, [Fe3S4]0, and has recently been identified in catalytic turnover states of nitrogenase. [60–62] It has been known for many years that integer-spin (non-Kramers) states having S ≥ 2 with negative zero-field splitting parameter D (so that the spin ground doublet is |S, ± MS〉 = ±S) exhibit EPR spectra, generally at low fields. [63, 64] More recently, it was shown that ENDOR and ESEEM of such EPR signals can be highly informative. [65–67]

Advanced EPR studies of FeS clusters in iron-sulfur and related proteins

This section describes advanced EPR studies that focus on the FeS cluster itself, using as probes primarily the Fe ions themselves (enriched in 57Fe), but also 1H nuclei located on coordinated thiolates that directly provide information on their nearby Fe ion. As discussed subsequently the inorganic sulfides can also be studied upon enrichment in 33S (I = 3/2, 0.75% natural abundance). In the case of heterometallic clusters, such as in nitrogenase FeMo-co, other nuclei can be studied, such as 95Mo (I = 5/2, 15.9% natural abundance, and enriched) and the central ion of FeMo-co, now identified as a carbide, due in part to enrichment in 13C. [68–70]

57Fe ENDOR

It is of interest to note that 57Fe studies of FeS clusters not only initiated the use of ENDOR in characterizing metalloenzymes, [7] but were the motivation [71] for the development of the theory and methodology for determining hyperfine interactions tensors through the simulation of 2D field-frequency patterns of ENDOR spectra collected across the EPR envelope of the center under study, [16, 26, 27] as well as the development of the most robust method for determining hyperfine signs, PESTRE. [45]

2Fe-Ferredoxins

The exchange coupling of the two iron spins, S = 2 FeII and S = 5/2 FeIII ions, in an EPR observable reduced [2Fe2S]+ cluster result in either a ferromagnetically [72] coupled ground state, which yields a total spin, S = 9/2, or an antiferromagnetically coupled ground state, which gives S = 1/2. [73] The observed g tensor for the antiferromagnetically coupled state is given by

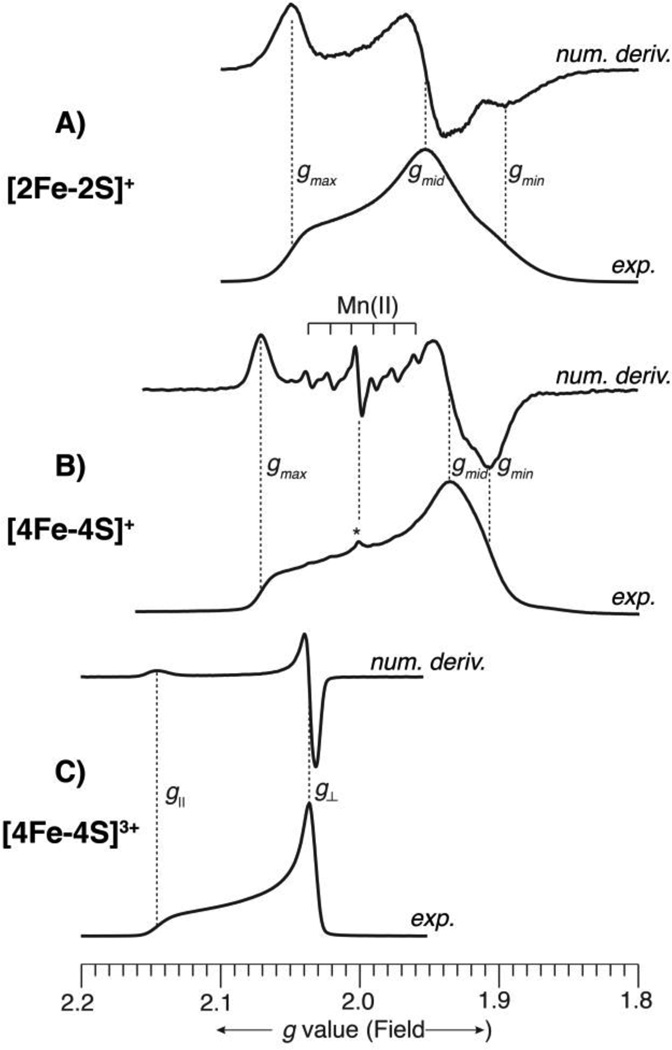

| (6) |

where gIII and gII are the individual g tensors of the ferric and ferrous centers, respectively. The low-spin S = 1/2 ground state is more commonly observed for [2Fe2S] clusters. Figure 4 presents Q-band (35 GHz) EPR spectra of three, representative FeS proteins with S = 1/2 ground states, including [2Fe2S]+ cluster from Aquifex aeolicus Fd1. The spectra were all recorded at 2 K under “rapid passage” conditions, [74] so that the experimental spectrum appears as an absorption line shape. In addition, for each protein, a numerical derivative spectrum is also provided, which thus has the first derivative line shape of an EPR spectrum recorded under “slow passage” conditions, as is the case for typically reported spectra. Each format has advantages and disadvantages. The absorption lineshape is better for observation of broad lines and gives a better idea as to the actual amount of signal. The first derivative lineshape is better for observation of narrow lines. This can easily be seen in Figure 4B, wherein the spectral signature of a small amount of adventitious Mn(II), which appears as a sextet due to hyperfine coupling to 55Mn (I = 5/2, 100%) is greatly accentuated in the digital derivative presentation, even though the Mn(II) is actually present in very low concentration, as shown by the experimental, absorption lineshape, which is dominated by the much broader [4Fe4S]+ EPR signal. and an oxidized 2Fe-Fd [2Fe2S]+ (Figure 4A), which has a significantly rhombic signal with g values straddling 2.0 (g = [2.05, 1.95, 1.89], giso = 1.96).

Figure 4.

Q-band (35 GHz) EPR spectra of three, representative FeS proteins. The spectra were all recorded at 2 K under “rapid passage” conditions, so that the experimental spectrum appears as an absorption lineshape. A digital derivative spectrum is displayed above each experimental spectrum, which gives the familiar presentation of EPR spectra. The intensities of all spectra have been arbitrarily scaled for ease of viewing. The abscissa is given in descending g value scale (corresponding to increasing magnetic field) to allow comparison among spectra recorded at slightly different microwave frequencies. The g values of the FeS clusters are indicated on each spectrum. A) Aquifex aeolicus reduced 2Fe-Fd, [2Fe2S]+, recorded at 35.028 GHz; B) Desulfovibrio gigas reduced 4Fe-Fd, [4Fe4S]+, recorded at 34.946 GHz; In (B), the presence of a small amount of adventitious Mn(II), a common occurrence in metalloprotein samples, is indicated. This narrow line sextet (55Mn, I = 5/2, 100%) is accentuated in the derivative presentation. An unknown radical (g ≈ 2.00) is also present in very small amount and is indicated by an asterisk. C) Halorhodospira halophila (formerly Ectothiorhodospira halophila) oxidized HiPIP, [4Fe4S]3+, recorded at 34.958 GHz.

Either of the S = 1/2 or 9/2 paramagnetic states for [2Fe2S]+ clusters are amenable to ENDOR characterization of both the 57Fe centers and of coordinated ligands and other nearby molecules. Both 57Fe ENDOR and magnetic Mössbauer spectroscopies may characterize the electronic structure of the iron ions of a given FeS center. [64, 75] Each technique has distinct advantages and disadvantages. As discussed elsewhere, [13, 14, 20, 76] Mössbauer is able to detect all Fe sites in a given sample, while ENDOR observes only those interacting with unpaired electron(s). This fact alone can lead to complementary information being provided by the two techniques. For example, Mössbauer is able to characterize the diamagnetic, reduced [2Fe2S]0 S = 0 ground state, inaccessible by ENDOR, as well as other paramagnetic, or integer-spin systems (S = 1, 2, …), which are more difficult, but not impossible (vide supra) to study by EPR and ENDOR. However, Mössbauer may be overwhelmed when multiple FeS clusters reside within a protein, severely convoluting a spectrum. ENDOR, in contrast, has the advantage of being ‘blind’ to diamagnetic species and can select among paramagnetic FeS clusters whose EPR envelopes do not overlap. Indeed, the spin state selection of ENDOR plays a critical role in the study of some complex FeS systems. A more subtle distinction is that Mössbauer can determine 57Fe quadrupole splitting that is unattainable through ENDOR spectroscopy as this information arises from the nuclear excited state of 57Fe (I = 3/2), accessed by the γ-ray energy employed by Mössbauer. [77] Traditionally, an advantage of Mössbauer is that it allowed determination of the sign of hyperfine couplings, along with their magnitudes, while such sign information was not obtainable from ENDOR. However, as discussed above, newly developed ENDOR protocols for determining absolute hyperfine signs [20, 45, 46] have “leveled the playing field” between the two techniques in this regard.

The g tensor for [2Fe2S] clusters may be used to classify clusters into families and determine electronic characteristics [20], however it is the 57Fe hyperfine couplings that provide the deepest insight into their electronic structure and ENDOR spectroscopy has the added advantage of being able to map the g tensor orientation onto the molecular frame.

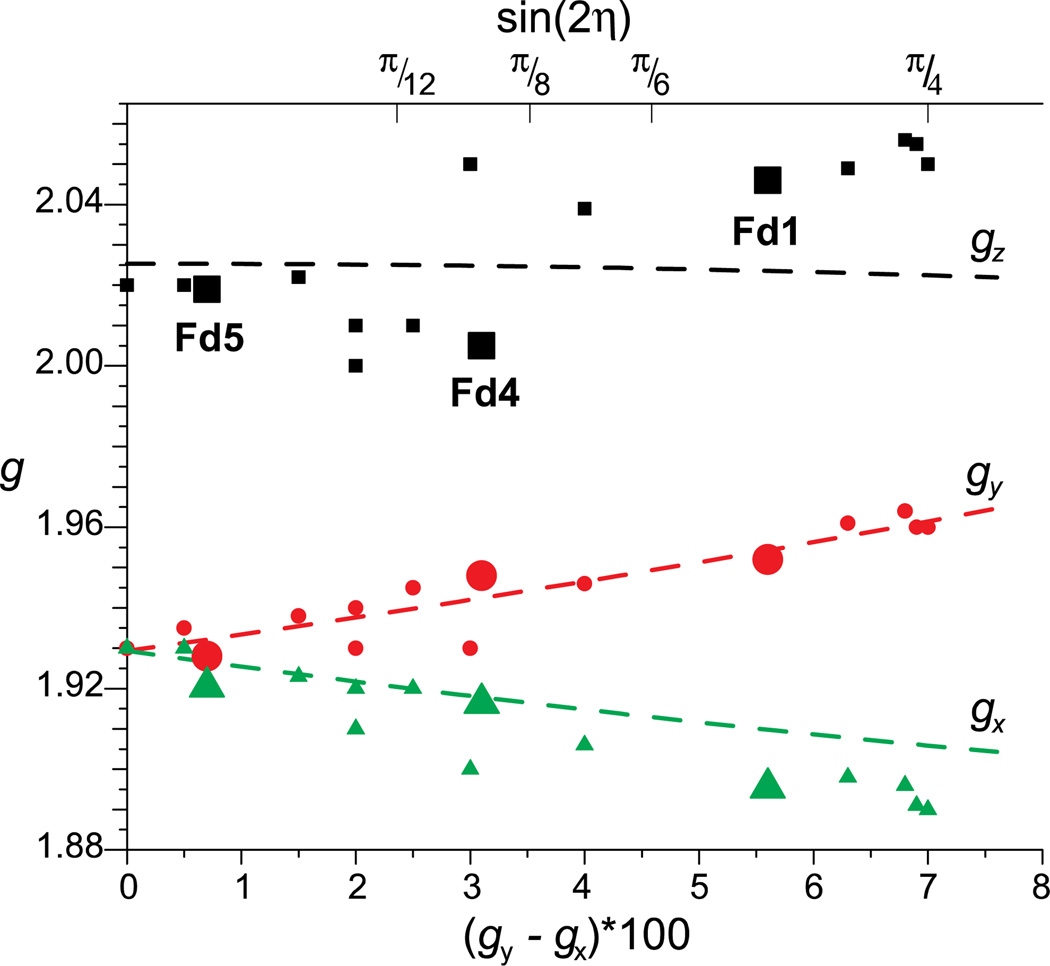

The [2Fe2S]+ clusters from Aquifex aeolicus (Aae) ferredoxins (Fd1, Fd5, and Fd5) are cysteine coordinated and belong to a giso = 1.96 subclass of 2Fe ferredoxins. [20] By grouping [2Fe2S] proteins into subclasses of related electronic structure, various ligand-field energies may be determined from EPR parameters as shown recently for Fd1, Fd4, and Fd5 from Aae. Such [2Fe2S]+ clusters exhibit fairly isotropic FeIII coupling, while the hyperfine coupling of the FeII ion is very anisotropic with its strongest hyperfine coupling along g1. The constituent FeIII ion in a [2Fe2S]+ cluster is relatively insensitive to its coordination environment, which is expected due to the spherical electron distribution of its high-spin d5 (half-filled) electronic configuration. [18, 20, 78, 79] In contrast, the ligand field of the FeII ion is very sensitive to its coordination environment as a result of the unsymmetrical electron distribution of its high-spin d6 configuration. The differences in the average of g values for different classes of [2Fe2S] clusters reflect the environment of the FeII site. [80] The dictates the ligand field energy d6, FeII ion controls the rhombic splitting of the cluster g tensor, which is proportional to the mixing of pure d(z2)(5A1) (axial compression) or d(x2 − y2)(5B1) (axial elongation) states of FeII for D2d symmetry. For giso = 1.96 class of [2Fe2S] proteins, the various ligand-field energies of the FeII ion in its ground state may be determined from fitting the g values to a diagonalized energy matrix for two pure z2 and x2−y2 states (diagonal terms) and the amount of rhombic crystal field mixing (off-diagonal terms) due to a rhombic crystal-field distortion (D2h → C2v). Thus, the plot of rhombic splitting versus canonical g values yields the ligand-field parameters for a given class of [2Fe2S] clusters. Figure 5 presents a solution to Eqs. 6 and 8 with ligand-field parameters given in the figure caption.

| (7) |

| (8) |

The amount of orbital mixing is proportional to the rhombic splitting of g, Δg⊥ = g3 − g2, and is a function of the fictitious angle 2η (Figure 5). [20]

Figure 5.

‘Bertrand plot’ of g tensor components against Δg∞ (×100) for various [2Fe–2S] proteins of the giso = 1.96 subclass. Dashed lines represent values from Eqs. 6 – 8 calculated with the parameters λ = −60 cm−1, ΔExy = 15,000 cm−1, ΔExz = ΔEyz = 5,000 cm−1, g(57FeIII) = 2.01. Reprinted from Figure 5 of Cutsail, et al. [20] with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media © 2012 SBIC.

As the EPR spectrum is influenced by the symmetry of the FeS cluster, the same is obviously true for the iron hyperfine couplings. High precision ENDOR of the 57Fe hfc of Fd1, Fd4, and Fd5 from Aae reveal isotropic FeIII hyperfine couplings, matching those previously established by Mössbauer spectroscopy. The FeII hyperfine couplings are vastly different for Fd1 and Fd5 which happen to be remarkably similar in structure. Further investigation of the slight differences in the structural, electronic, hyperfine properties of characterized ferredoxin proteins needs to be done to achieve a more general understanding of the mixed valent [2Fe–2S] cluster. Understanding of the simplest FeS cluster serves as a building block for understanding higher nuclearity FeS clusters.

4Fe-Ferredoxin Overview

Various oxidation states of [4Fe4S] clusters are observed, ranging from the 3+ state seen in oxidized high potential iron-sulfur protein (HiPIP-ox), to 2+, 1+, and 0. Only 3+, S = 1/2, and 1+, S = 1/2 or S = 3/2, cluster oxidation states possess paramagnetic ground spin states and are amenable to typical advanced EPR spectroscopies. [81–83] The other, diamagnetic 2+, S = 0, and 0, S = 4, oxidation states may be observed through Mössbauer spectroscopy. The ground spin states are most conveniently explained by antiferromagnetic coupling of [2Fe2S] cluster pairs (the so-called 2-2 model), ([2Fe2S]2+, S = 5; [2Fe2S]+, S = 9/2; [2Fe2S]0, S = 4) and the FeII S = 2 and/or FeIII S = 5/2 ion(s). The common [4Fe4S]3+ S = 1/2 state is the result of an [2Fe2S]+ (Fe2.5-Fe2.5) S = 9/2 pair antiferromagnetically coupled with two FeIII S = 5/2 ions. The two electron reduced [4Fe4S]+ is composed also of an [2Fe2S]+ (Fe2.5-Fe2.5) S = 9/2 pair however it is antiferromagnetically coupled with two FeII S = 2 ions. [18, 84] Examples of an oxidized HiPIP [4Fe4S]3+ and a reduced [4Fe4S]+ are exhibited in Figure 4. The oxidized HiPIP [4Fe4S]3+ exhibits an axial, narrow linewidth signal, with g values above 2.0 (g‖ = 2.14, g⊥ = 2.04, giso = 2.07) and the reduced 4Fe-Fe [4Fe4S]+ has a broader linewidth, slightly rhombic signal with g values straddling 2.0 (g = [2.07, 1.94, 1. 91], giso = 1.97). It should be noted, as can be seen by comparison of Figures 4A and 4C, that it is essentially impossible to distinguish solely by EPR between 4Fe-red and 2Fe-red centers. As described below, the specific nature of the coupling can be variable and more intricate than indicated here.

4Fe-Ferredoxin Models

The synthesis of small molecule model compounds of the active site center of ferredoxins and other FeS cluster species was a great achievement of inorganic chemistry that has been extensively reviewed elsewhere. [85–87] Of relevance here is the use made of several synthetic ferredoxins for detailed EPR and ENDOR studies by Gloux, Lamotte, Mouesca, and co-workers in Grenoble. [18, 88–93] The synthetically accessible cluster, [Fe4S4(SR)4]2− (where R = Ph (-C6H5), Bz (-CH2C6H5)) is diamagnetic and corresponds to the 4Fe-ox (or HiPIP-red) protein cluster forms. These workers were able to generate EPR active forms of the synthetic clusters by low-temperature γ-irradiation of single crystals, this process, which has also been used extensively with metalloproteins in frozen solution, [94] [95] [96] generates free electrons which can then reduce the FeS center to generate [Fe4S4(SR)4]3−, the analog to the 4Fe-red cluster. In addition, oxidized clusters, [Fe4S4(SR)4]1−, can also be concurrently generated, analogous to the HiPIP-ox form. The different EPR signatures of these species allowed their deconvolution in single-crystal EPR spectra. [90, 92, 97] In these synthetic clusters, the only ENDOR active nucleus is 1H, with the methylene hydrogen atoms of the benzylthiolato (or related) ligands serving as models for the β-H atoms of cysteinyl ligands in FeS clusters. [89, 93] Nevertheless, 1H ENDOR has provided a wealth of information on the electronic structure of these 4Fe4S model compounds. All eight 1H hyperfine tensors were fully determined for [Fe4S4(SCH2C6D5)4]1−, wherein the benzene ring deuteration assisted in simplifying the 1H X-band ENDOR spectra. The results on hydrogen dipolar coupling and spin distribution within the cluster could be related to those from paramagnetic NMR and allowed a proposal to be made as to the specific spin coupling state, namely |Smixed-valence, Sferric, Stotal〉 = |7/2, 3, 1/2〉, as opposed to |9/2, 4, 1/2〉, [89] (note that in some 2Fe-Fds, Smixed-valence = Sferric + Sferrous = 5/2 + 2 = 9/2, and 0 ≤ Sferric ≤ 10 (+ 5/2 + 5/2)). The same parent compound, in the reduced form generated by γ-irradiation was later studied by Q-band 1H ENDOR. [98] It was possible to determine the full hyperfine tensors of all eight benzyl methylene hydrogen atoms, plus three more tensors from 1H nuclei on adjacent molecules. Analogously to the earlier study, the spin distribution within the 4Fe-red model cluster was determined, including the spin projection onto each Fe ion, which is crucial for understanding hyperfine coupling to bound substrate in enzymatic FeS clusters. In this cluster, the spin coupling ground state was determined to be |S34, S134, Stotal〉 = |4, 2, 1/2〉, using the so-called ‘3-1’ scheme, wherein the three formally ferrous ions (FeII1, FeII3, and FeII4) are coupled to give first S34 (0 ≤ S34 ≤ 4; here 4) and then S134 = S34 − S2 = 4 − 2 in this case, which is then antiferromagnetically coupled to the ferric ion: Stotal = S134 − S2 = |4 − 5/2| = 1/2. An alternate, and widely used coupling scheme (vide supra), although considered less physically sound for [Fe4S4]+ by Moriaud et al. [105], is the ‘2-2’ scheme which is analogous to that used above for [Fe4S4]3+, namely, Smixed-valence = S12 = 9/2 (or lower) and Sferrous = S34 = 4 (or lower), with Stotal = S12 − S34 = |9/2 − 4| = 1/2. Using the 2-2 model, the [Fe4S4(SCH2C6D5)4]3−, is best represented as |Smixed-valence, Sferrous, Stotal〉 = |S12, S34, Stotal〉 = |7/2/, 3, 1/2〉; the spin coupling scheme analogous to that for the HiPIP-ox model cluster.

The Grenoble workers were also able to prepare [57Fe4S4(SCH2C6H5)4]2−, and made 57Fe X-band ENDOR measurements of γ-irradiated species that allowed the determination of the full 57Fe hyperfine coupling tensors of all four Fe sites in a [Fe4S4]3+ cluster. [88] Subsequently, thanks to the advantages provided by Q-band ENDOR, namely shifting the 1H ENDOR resonances far from those of 57Fe as well as providing greater g value dispersion, Moriaud et al. [105] were able to study successfully a 4Fe-red model, [57Fe4S4(SCH2C6H5)4]3−, and determined the full 57Fe hyperfine tensors in this cluster as well. [88] These landmark experimental results on model compounds have been crucial in subsequent theoretical studies of FeS cluster electronic structure, [91] and have been extremely helpful in providing benchmarks for understanding biological FeS clusters for which such high precision single-crystal ENDOR studies are not feasible.

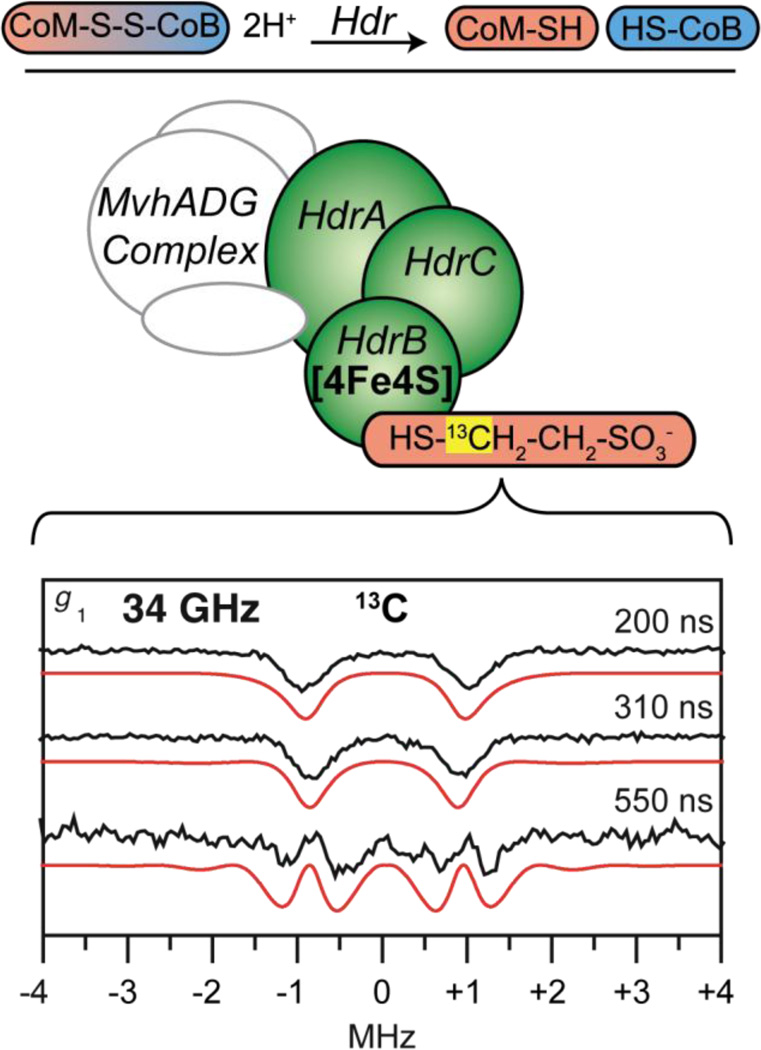

Heterodisulfide reductase

During the final methane forming step by methanogenic archaea, a mixed disulfide of coenzyme M (CoM, mercaptoethane sulfonate) and coenzyme B (CoB, 7-mercaptoheptanoyl-L-threonine phosphate), CoM-S-S-CoB, is formed. [99] Methanogens from Methanothermobacter marburgensis do not contain cytochromes and must reduce CoM-S-S-CoB by other means, as the regeneration of the individual CoM-SH and CoB-SH thiols is needed for continued methane formation. [100] The exothermic reduction of this disulfide is performed by heterodisulfide reductase (Hdr), a part of the proposed hydrogenase-heterodisulfide reductase complex, MvhADG-HdrABC. [99] Hdr is composed of three subunits, HdrA containing a FAD bonding motif as found from primary sequence data and four [4Fe4S] cluster binding sites, based again on the primary sequence. HdrC contains two additional [4Fe4S] binding sites. The subunit of disulfide reduction, HdrB, contains a bound [4Fe4S] cluster in a C-terminal CCG motif (CX31–39CCGX35–36CXXC) and a bound zinc to the N-terminal CCG domain. [101]

HdrABC in the presence of only CoM (CoM-HdrABC) exhibits an EPR signal below 50 K from a paramagnetic S = 1/2 species which has g values similar to those of the oxidized form of HdrB. This S = 1/2 signal of CoM-HdrABC is lost upon the addition and reaction of CoB-SH, which reduces the [4Fe4S] cluster. The reduction of the FeS cluster observed by EPR, hyperfine broadenings of the EPR signal from 57Fe enriched enzyme [102] and 33S-labeled CoM-SH, [103] combined with variable-temperature magnetic circular dichroism (VT-MCD) experiments, [104] led to the suggested [4Fe4S]3+ formal charge of the CoM substrate bound cluster in the CoM-HdrABC complex.

Previous 9 and 95 (W-band) GHz ENDOR of CoM-Hdr exhibited unusually isotropic 57Fe couplings of four distinct iron responses for an [4Fe4S] cluster, with respective signs implied from polarized patterns of the W-band ENDOR responses. [105] The cluster is observed only under oxidizing conditions, with two iron hyperfine couplings resembling an (Fe2.5+–Fe2.5+) pair, [18] indicating the cluster is [4Fe4S]3+, however, this is not supported by the observed average of Hdr-CoM g values, giso < 2.0, which contrasts to what is observed for well-known [4Fe4S]3+ clusters, such as oxidized HiPIPs, which have g values > 2.0 [92] (see Figure 4).

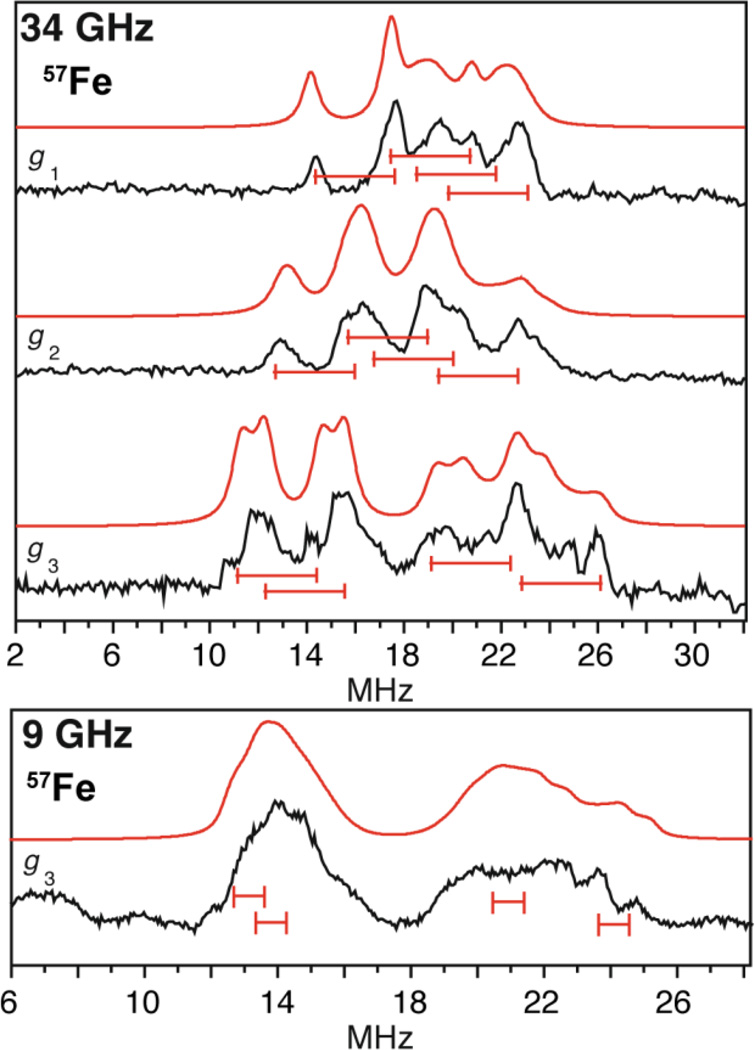

The 34 GHz 57Fe ENDOR spectra of CoM-HdrABC and HdrB in an oxidized form (HdrBoxid) (Figure 6), unambiguously resolve all four iron sites of the [4Fe4S] cluster [106] and provide improved resolution over the earlier W-band results. [105] Using the hyperfine sign results previously found for CoM-HdrABC from 95 GHz ENDOR spectroscopy, [105] a mixed valence pair, Fe2.5+–Fe2.5+, with isotropic coupling of approximately −30 MHz is observed, along with a ferric pair, FeIII–FeIII, with coupling of approximately +20 MHz, which together are typical for an [4Fe4S]3+ S = 1/2 cluster and have been observed previously for other HiPIP proteins [18] and are almost identical to that of the oxidized HiPIP [4Fe4S]3+ cluster in Chromatium vinosum measured by Mössbauer spectroscopy. [107]

Figure 6.

The 57Fe ENDOR of the [4Fe4S] cluster of the HdrB subunit taken at Q- and X-band frequencies with A/2 centered goalposts in red of length equal to 2νn. The higher frequency, Q-band (34 GHz) ENDOR generated better separation of the 57Fe hyperfine as 2νn is much greater from the higher magnetic field than that employed at X-band (9 GHz) frequency. 57Fe ENDOR reprinted from Figure 2 of Fielding, et al. [106] with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media © 2013 SBIC.

These 57Fe hyperfine couplings are in the ‘strong coupling’ regime where the ENDOR response at each microwave frequency is centered at A/2. The increased separation of the ENDOR ν+/− doublets at Q-band frequency and correspondingly higher magnetic fields yielded higher resolution of the four iron hyperfine couplings compared to the situation at X-band measurements, Figure 6.

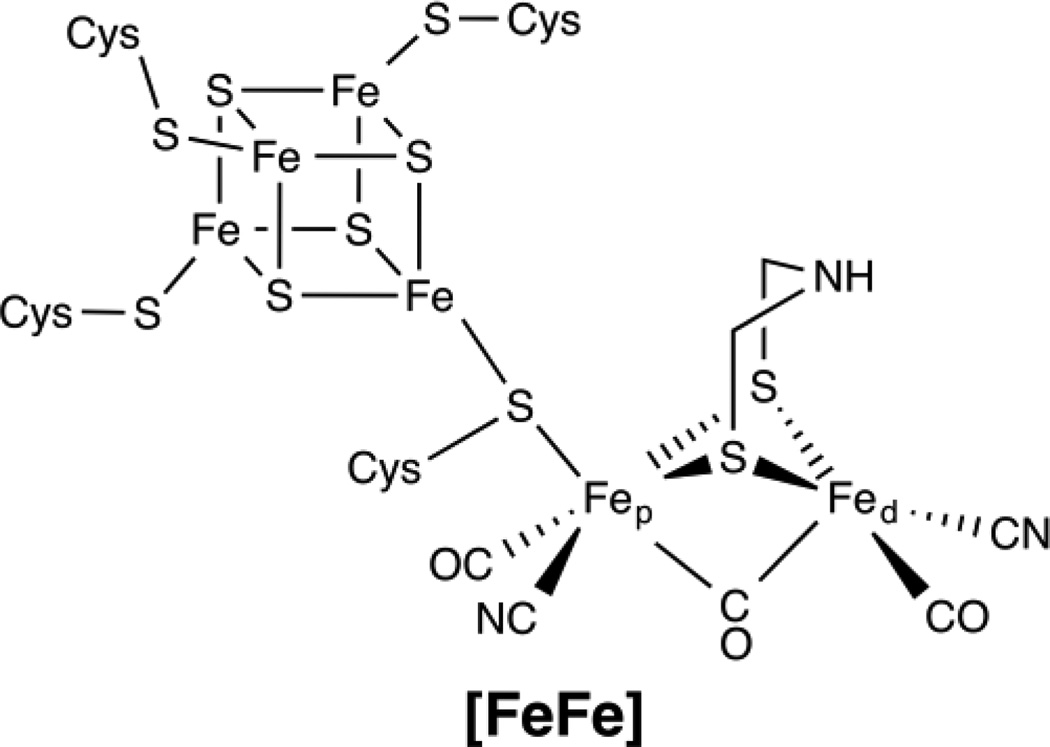

Hydrogenase

The hydrogenase enzymes consist of three classes, separated by their metal cofactor active sites: the mononuclear iron [Fe]-, diiron [FeFe]-, and the [NiFe]-hydrogenases. [108] The active site of the [FeFe] enzymes is shown in Figure 7. Both [FeFe] and [NiFe]-hydrogenases contain multiple FeS clusters for electron delivery to their active sites, however the [FeFe]-hydrogenase uniquely contains an [4Fe4S] cluster that is completely cysteinyl coordinated and is bound to the proximal iron (Fep) of the active site diiron center (H-cluster) through a cysteine thiolate bridge conserved throughout the [FeFe] hydrogenases. [109, 110] The proximal (to the [4Fe4S] cluster) iron, Fep, and the distal iron, Fed, each contain CO and CN− exogenous ligands, and are bridged by a CO and two thiolate bridges from a dithiolate moiety, unique to [FeFe]-hydrogenases. [108]

Figure 7.

Hydrogenase Active Site Structure; iron-only [FeFe] hydrogenase.

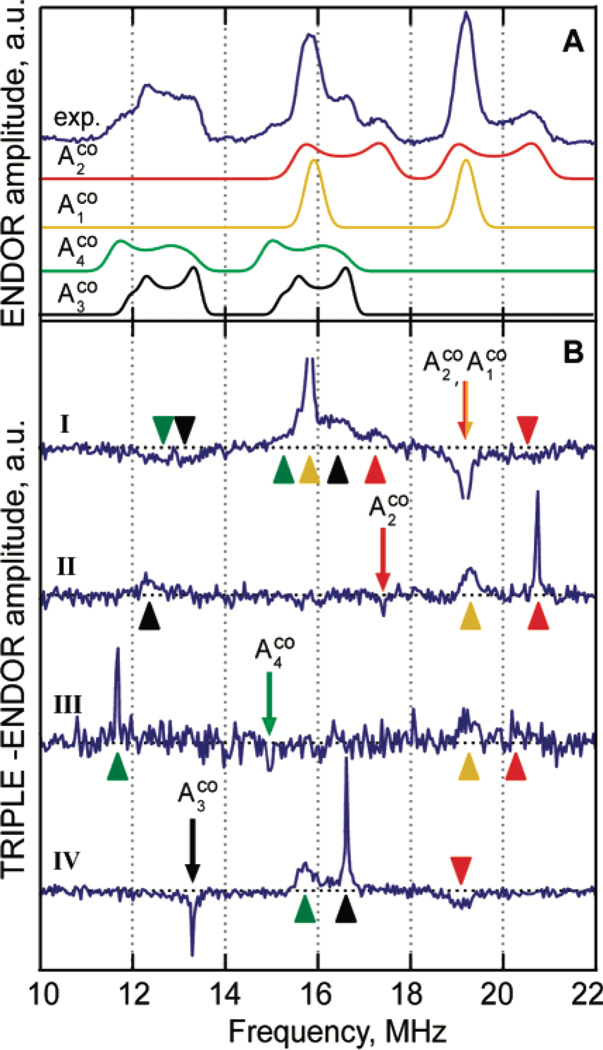

While the advanced EPR spectroscopic characterization of hydrogenase has provided an abundance of information including ligand unpaired spin density, [111] thiolate bridge atom identification, [112–115], cluster assembly, [113, 116–120] [121] and model complexes, [122–124] all extensively reviewed elsewhere, [108, 116, 125] we will briefly show the particular example of the 57Fe ENDOR and HYSCORE work of the [4Fe4S] cluster of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase. [41] This study determined that the Fep of the paramagnetic [Fe1+–Fe2+] oxidized H-center is in the FeI oxidation state and binds to the cuboidal [4Fe4S] cluster, while the distal iron, Fed, alternates between FeI (reduction) and FeII (oxidation) states. It is the paramagnetic FepI (3d7) ion that is the source of unpaired electron spin density that contributes to all iron hyperfine values observed for the formally diamagnetic [4Fe4S]2+ center via spin density distribution across the entire 6Fe center. [41] All six iron hyperfine values were determined, the four of the [4Fe4S] cluster through ENDOR spectroscopy, with their overlapping, orientation-dependent pattern deconvoluted through the use of pulsed Davies TRIPLE experiments, a ‘pump–probe’ technique. [37] The weaker hyperfine values of the [FeFe] active site were determined through HYSCORE spectroscopy. [41] This tour de force combination of advanced EPR techniques has fully characterized the iron electronic structure of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase.

Nitrogenase

ENDOR and ESEEM spectroscopies have been applied extensively to the “Everest of metalloenzymes” in an effort to shine light on biological reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia. [14, 58–60, 126] The complex mixed-metal active site of nitrogen reduction by nitrogenase, FeMo-co (Fe7S9CMo). As noted above, the early development of orientation-selective ENDOR occurred in the context of X-band 57Fe field-modulated CW ENDOR studies of the resting-state (S = 3/2) FeMo-co. The hyperfine tensors thus derived [127–129] were later used for the Mössbauer analysis [130] More recently, 35 GHz 57Fe ENDOR was used to identify the different CO-bound inhibitor states. [131, 132]

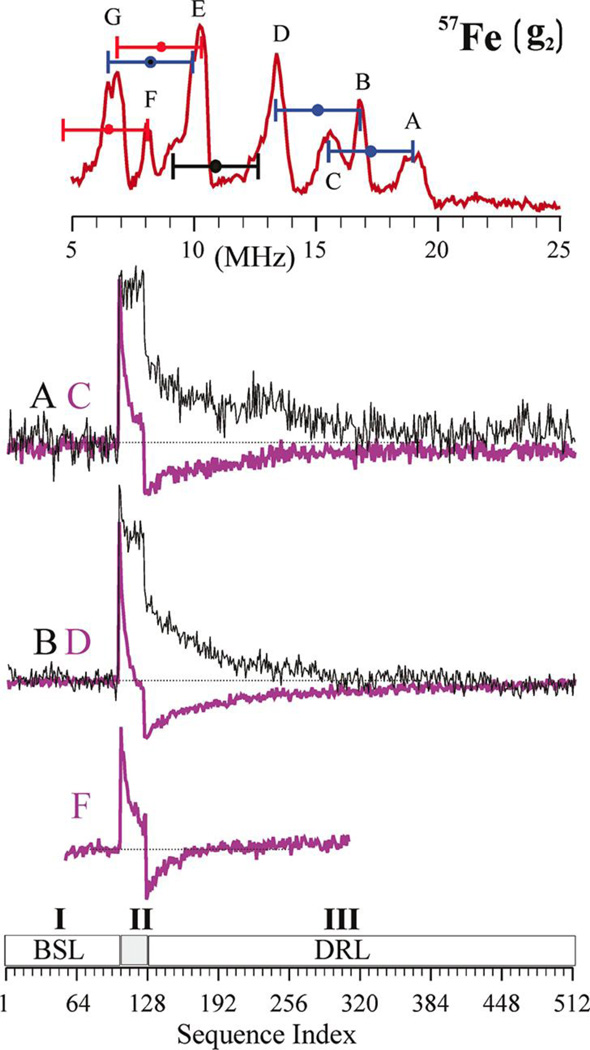

Most recently, 35 GHz Davies pulsed 57Fe ENDOR was combined with the PESTRE techniques to allow the characterization of all seven of the Fe sites in an S = 1/2 hydrogen turnover state of FeMo-co that has accumulated four electrons/protons, stored as two hydrides that bridge Fe and two protons. [46] 57Fe ENDOR studies yield the hyperfine tensors for five Fe sites of this intermediate and the coupling magnitude of a sixth. TRIPLE ENDOR provided valuable assistance in decomposing overlapping 57Fe responses. Pulsed ENDOR Saturation and Recovery (PESTRE) allowed a direct measurement of the hyperfine signs, Figure 9. The PESTRE protocol employs three stages of Davies microwave pulse sequences: (I) no applied RF, to establish an electron spin echo baseline; (II) applied RF at the frequency of the probed ENDOR transition, applied to saturate the response; (III) RF frequency turned off, to monitor the ESE relaxation behavior which is characteristic of the ratio of A/gn. A particular benefit of this technique is that it does not require comparison of the intensities of ν+ and ν− branches of an ENDOR spectrum, giving reliable sign information from a single branch.

Figure 9.

Determination of signs of hyperfine couplings at g2 by PESTRE technique at Q-band. Top: Davies ENDOR spectrum indicating the ENDOR peaks being interrogated. The goalposts here are color coded to indicate sign of hyperfine coupling: blue, negative; red, positive; black, undetermined. Center: PESTRE traces, presented as the difference between the observed ESE signal and the BSL (ΔESE) recorded at: upper set: peaks A (black trace) and C (purple trace); middle set: B (black trace) and D (purple trace); lower: F (purple trace). Bottom: schematic of the PESTRE protocol showing Stage I (RF off, BSL); Stage II (RF on, ENDOR signal); Stage III (RF off, DRL). Reprinted with permission from Doan, et al. [46] Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

Through the use of a sum-rule on the spin projection coefficients, [18] the magnitude and sign of all seven Fe sites are found. The significance of these measurements is to account for the four additional electrons of the E4 state compared to resting state (E0), using the Lowe-Thorneley scheme for nitrogenase intermediates. [133] The 57Fe hyperfine character reveals that the formal redox state of the E4 intermediate is the same as the resting state cluster, although it has four additional electrons. Therefore, these additional electrons must be ‘stored’ on 2 of the 4 protons of the E4 intermediate as bridging hydrides, yielding critical insight into the nitrogenase mechanism.

Other Components: Heterometal

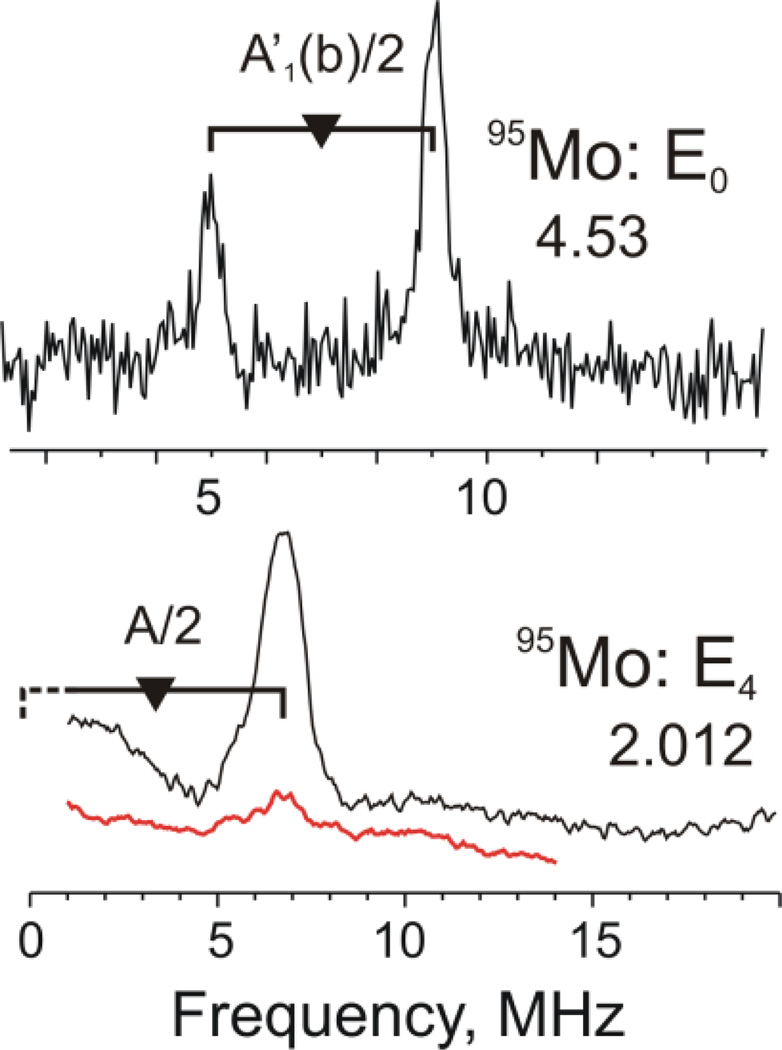

95Mo ENDOR

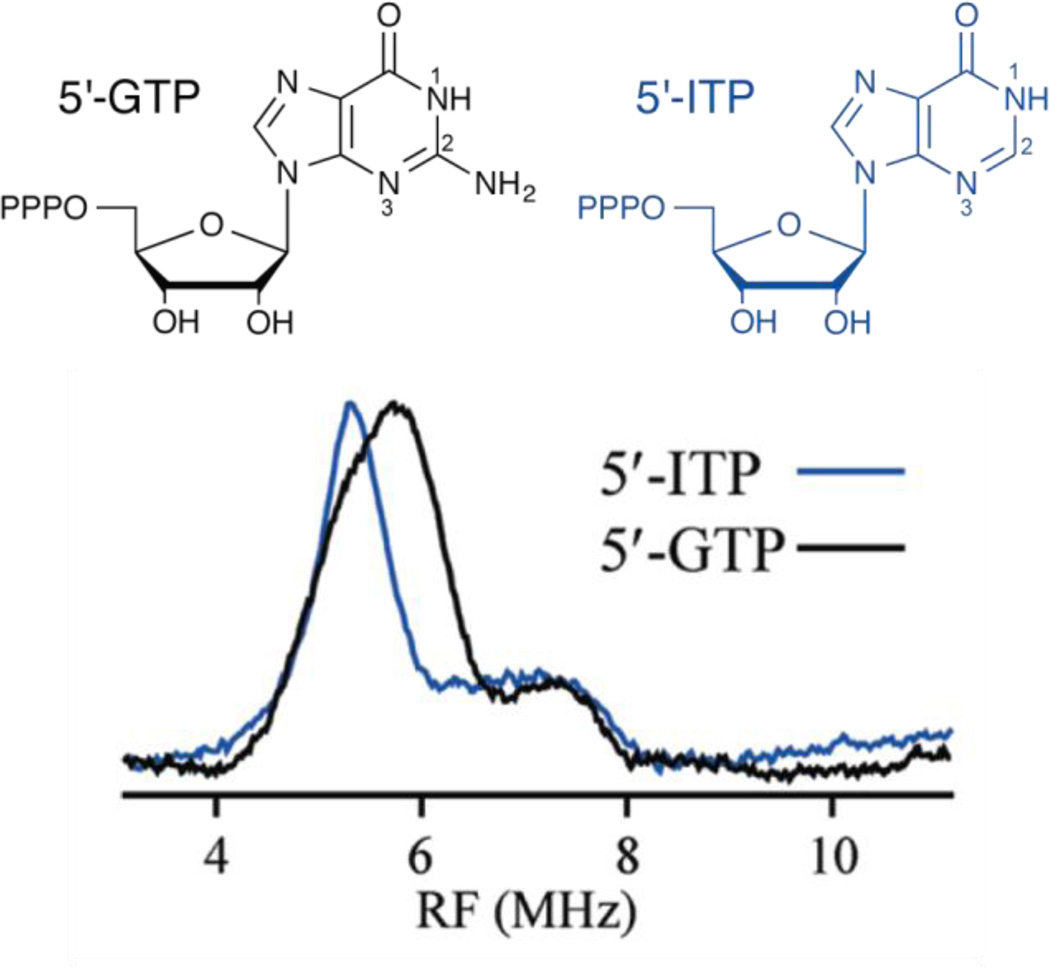

The nitrogenase α-70Ile MoFe protein described above contains two metal-bridging hydrido ligands, as characterized by 1,2H ENDOR. [134] Although hydride binding only to Fe sites seemed more plausible, it was important to test the possibility of hydride binding involving the Mo ion. The Davies ENDOR studies at multiple magnetic fields of the 95Mo-enriched intermediate showed that the isotropic 95Mo hyperfine coupling was extremely small, aiso ≈ 4 MHz, decreased from that in the resting state (Figure 10). This aiso value is at least five-fold less than the lower bound required by the 1,2H ENDOR measurements for Mo to be involved in forming a Mo-H-Fe, hydride. These measurements thus led to the conclusion that this catalytically central intermediate contains two Fe-H-Fe moieties. [60]

Figure 10.

(top) Davies 95Mo-ENDOR spectra of 95Mo-enriched (black) and natural-abundance (red) α-70Ile MoFe protein: (top) in the resting state. (E0); (bottom) CW 95Mo ENDOR of trapped intermediate (E4) state. Reprinted with permission from Lukoyanov, et al. [135] Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

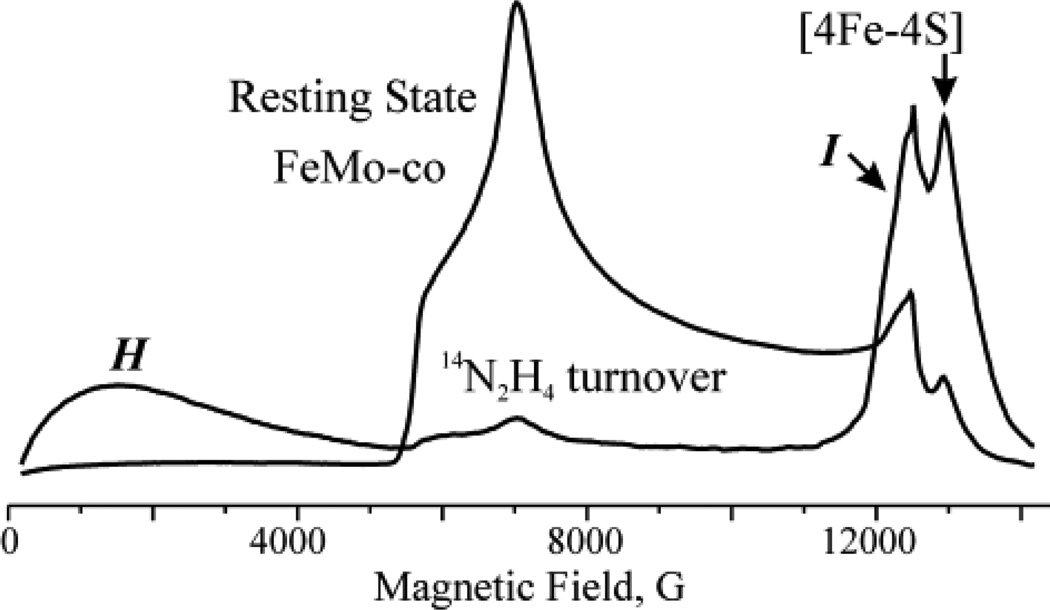

95Mo NK-ESEEM of a Nitrogenase S ≥ 2 Catalytic Intermediate

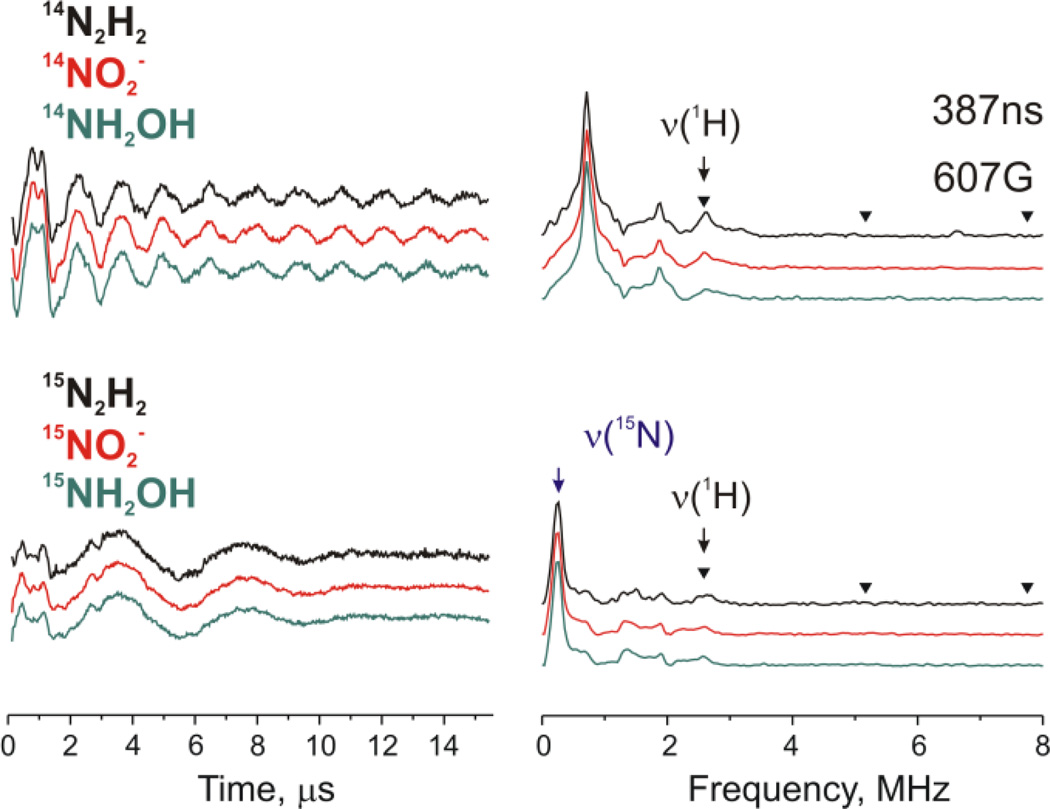

Rapid freezing during turnover of a remodeled nitrogenase MoFe protein (α-70Val→Ala, α-195His→Gln) with the electron-transfer Fe protein and with the substrates diazene, methyldiazene (HN=N-CH3), hydrazine, NO2−, or NH2OH each results in the loss of the resting-state signal from the catalytic FeMo-co and appearance of the signals from two new signals, Figure 11. [62] One signal (denoted I) appears in the vicinity of g2 and has S = 1/2. A second signal (denoted H) is seen as a broad featureless absorption that begins near zero field and extends to ~ 5000 G (at Q-band). Such an EPR signature arises from an FeS cluster in an integer-spin, ‘non-Kramers (NK)’ state with S ≥ 2. [62, 136] and could potentially be due to a variety of FeS systems; in nitrogenase, there are three such possibilities: the catalytically active FeMo-co cluster, the electron-transfer P-cluster (Fe7S9) also present in the MoFe protein; and [4Fe4S] cluster in the Fe protein.

Figure 11.

35 GHz CW EPR spectra (absorption-display) of resting-state FeMo-co and from freeze-trapped turnover intermediates H and I. Note that resting state FeMo-co has S = 3/2 ground state and effective g values of [4.3, 3.64, 2.0] and the H intermediate has S = 2 ground state and very high effective g values (low field transitions).

NK-ESEEM [65, 67] was able to identify the source of the H signals. NK-ESEEM time-waves of the H signal of 95Mo enriched MoFe protein produced significant changes of the NK-ESEEM time-wave, which established that this NK-EPR signal arose from the Mo-containing FeMo-co in an integer-spin state, and not the all-iron P or [4Fe4S] clusters. [62]

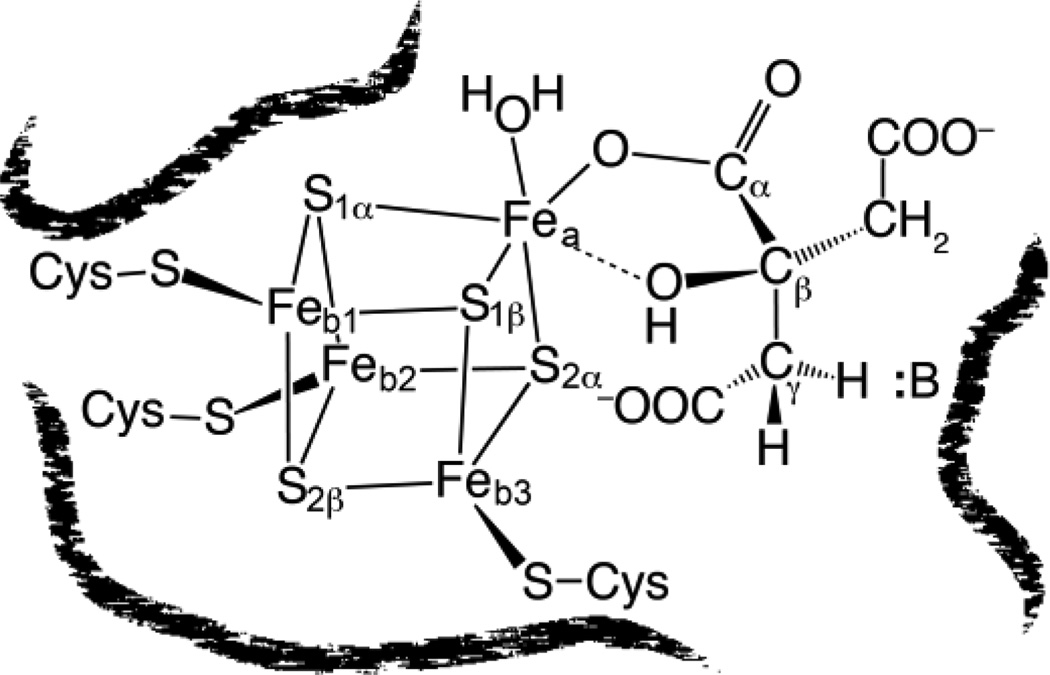

Other Components: Sulfide

The first 33S ENDOR measurements were performed on the reduced cluster of aconitase, and analysis of 33S resonances from the [4Fe4S]+ cluster of the enzyme-substrate complex suggested that the sulfur sites occur as two pairs (Sαl, Sα2; Sβ1, Sβ2) with remarkably small spin density on sulfur, and even disclosed their spatial relation to the Fe sites. [137] Figure 12 summarizes the information from the 57Fe and 33S studies about the four Fe and four inorganic sulfides, placing it within the context of the X-ray diffraction structure, [138] which showed that cysteines are bound to the three iron ions that correspond to the three Fb seen spectroscopically. Subsequently, 33S ENDOR measurements were performed on the resting-state FeMo-co of nitrogenase. [128] We should note that the substitution of NMR/ENDOR-active 77Se (I = 1/2) for S in a [2Fe2S] cluster was instrumental in deducing the stoichiometry of these clusters. [139]

Figure 12.

Aconitase Structure showing disposition of Fe and S ions as deduced from 57Fe ENDOR/Mossbauer studies and 33S ENDOR studies; structure of citrate bound to the unique Fea site of the [4Fe4S] cluster as deduced from ENDOR spectroscopy of substrates, as described below.

Cluster Ligation

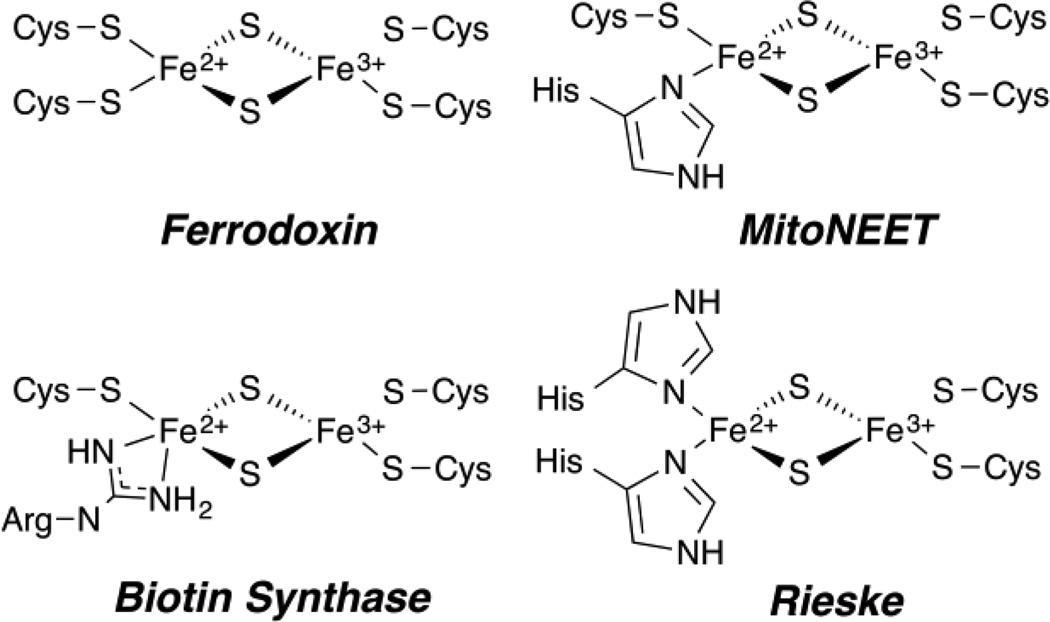

Nitrogenous Protein-Derived Ligands (Rieske and Fra2)

The [2Fe2S] cluster is found in many proteins across Nature and comprises several classes. These include clusters with complete cysteine coordination as in ferredoxins, [7, 8, 20, 140–143] or with some degree of noncysteine coordination. This section focuses on advanced EPR studies of the protein-derived, non-cysteinyl ligands of the FeS cluster. This situation was first examined for [2Fe2S] clusters with the Rieske and Fra2 proteins. Single histidine ligation (i.e., (Cys2 [FeIIIS2FeII]HisCys)) is found in the yeast regulatory protein Fra2-Grx3, which has been characterized by ENDOR, [144] and the human protein mitoNEET, and has been well characterized by advanced EPR. [78, 145–147] Double histidine ligation (Cys2 [FeIIIS2FeII]His2) occurs in the well studied Rieske proteins [79, 148–152]. These active site structures are all shown in Figure 13. We discuss here the more recent example of mitoNEET, and the demonstration that even arginine ligation exists, as in the sulfur atom donating [2Fe2S] cluster of Biotin Synthase. [153–156]

Figure 13.

[2Fe2S]+ Coordination in a variety of biological systems as indicated.

mitoNEET

The homodimeric [2Fe2S] human mitoNEET protein is located within the mitochondrial membrane. [147] This protein is known to interact with the thiazolidinedione class of diabetes drugs, however its primary function is currently unknown. [145] This [2Fe2S] cluster attained significant bioinorganic interest when it was revealed that it was coordinated by 3Cys 1His amino acids, [145] a first among [2Fe2S] proteins, differing from the all Cys ferredoxin class and 2Cys 2His Rieske class (see Figure 13). [79, 149–151, 157] The sole histidine of mitoNEET coordinates to the Fe through the Nδ of the imidazole ring, the same coordination as observed for each His in Rieske clusters. [145]

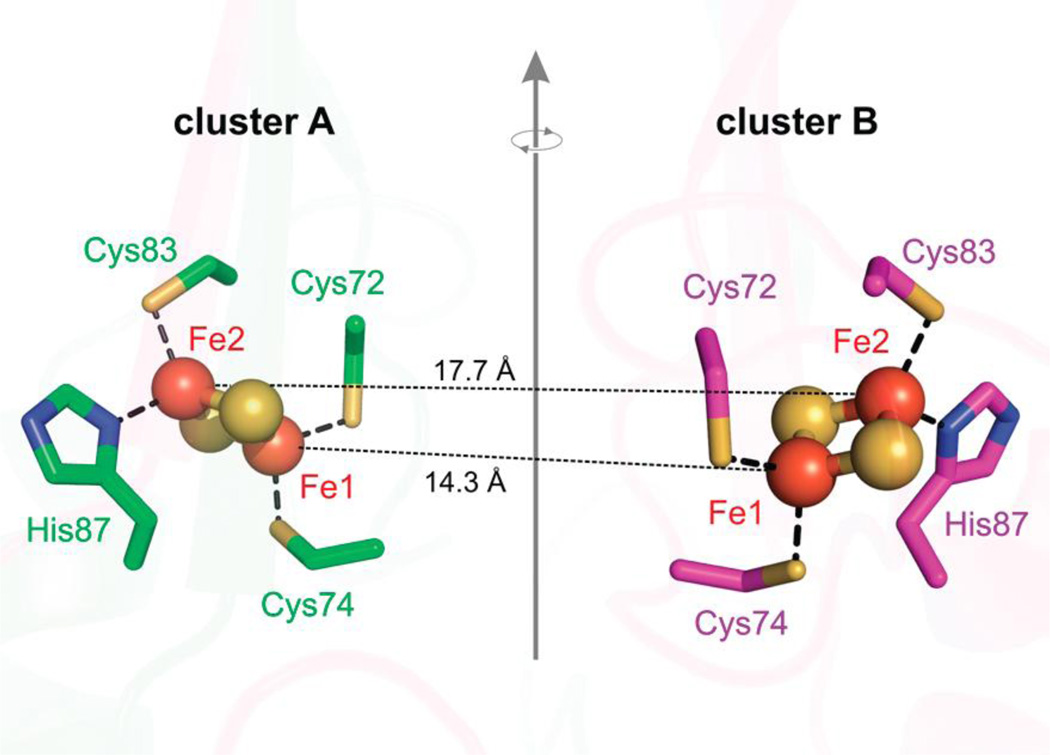

The multi-frequency EPR and ESEEM work at X- (9.5 GHz), Ka- (31 GHz), and ‘Q’- (34 GHz) bands elucidated the full structural characteristics the individual clusters and the dipole interaction of the two S = 1/2 [2Fe2S]+ clusters of the homodimer, [78] which are separated at a distance of 16 Å. [145] As is typically done, the Fe ions are separately described as a ferric, FeIII S = 5/2, and ferrous, FeII S = 2, ions and an antiferromagnetically coupled representation results in the observed S = 1/2 ground state. [20] The coupled representation for a [2Fe2S] cluster typically represents a single isolated FeS cluster well, however, the close proximity of the two [2Fe2S] clusters (~16 Å) of the homodimer was taken into consideration. The uncoupled representation employed by Dicus, et al. [78] employs the usual Fe ion spin projections (Eq. 6) [158] and sums of all dipolar interactions of every iron of the two [2Fe2S] clusters, both inter-cluster and intra-cluster dipole interactions, 6 interactions total. This approach was advantageous for the assignment of the [2Fe2S] iron oxidation states as the intra-cluster dipolar distances vary enough to yield predictable differences in Fe-Fe couplings. By mapping the Fe-Fe pairs onto the crystal structure the assignment of the FeII and FeIII oxidation states could be made to the specific iron sites of the [2Fe2S] clusters. In this model, the FeIII can either be coordinated by the two cysteines or by one cysteine and one histidine. Only an assignment where the FeIII-FeIII intra-cluster pair occupies the inner iron sites, i.e., those with the least separation (Figure 14), yields a dipolar coupling observable by X-band EPR. Therefore the FeII ions occupy the outer intra-cluster pair and have the single histidine ligand coordinated, as shown by ‘Fe2’ in Figure 14. [78]

Figure 14.

Two [2Fe2S] clusters, (iron, orange, sulfur, yellow) of the homodimer human mitoNEET separated by ~16 Å, related by a rotation around a 2-fold symmetry axis between the two monomers (green and pink). PDB ID 2QH7. Reprinted with permission from Dicus, et al. [78] Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

The small hyperfine interaction of the 14Nδ histidine was amenable to ESEEM spectroscopy, and multi-frequency microwave instrumentation allowed for the deepest available modulation to be obtained. To obtain the deepest amount of modulation, increased ESEEM signal, one may aim to be within the ‘cancelation regime’ where one electron manifold (MS) is nearly canceled. This is the case when the hyperfine energy is (approximately) equal to twice its Larmor frequency. [159] Recall, as the microwave frequency of instrument is increased, the Larmor frequency of the resonant nuclei scales linearly. For example, the Larmor frequency of 14N is approximately 1.03 MHz for a g = 2 field position at X-band (9.5 GHz), but will increase to 3.40 and 3.84 MHz for the same EPR transition at Ka (31 GHz) and Q-band (35 GHz), respectively. One of the largest advantages of moving in microwave frequency from X- up to Q-band is that proton resonances are shifted from the nitrogen region as the proton, with its large gN value, Larmor frequency moves from 14 MHz to > 50 MHz.

The mid-range frequency ESEEM studies by Dicus, et al. [78] assigned the coordinating histidine nitrogen, Nδ, to the FeII ion of the reduced [2Fe2S]+ cluster of mitoNEET. As 15N lacks a quadrupole moment, the transitions obtained by ESEEM are a result of only the anisotropic portion of the hyperfine tensor, allowing for a more direct estimate of the dipolar contribution, which can be used in refining the 14N ESEEM analysis. The values of (15N)aiso = 8.77 MHz and T = 1.77 MHz obtained by both Ka- and Q-band ESEEM were consistent with both Q-band Davies ENDOR and HYSCORE spectroscopies, demonstrating the accuracy of obtaining the 15N hyperfine tensor through ESEEM at either Ka or Q band microwave frequencies.

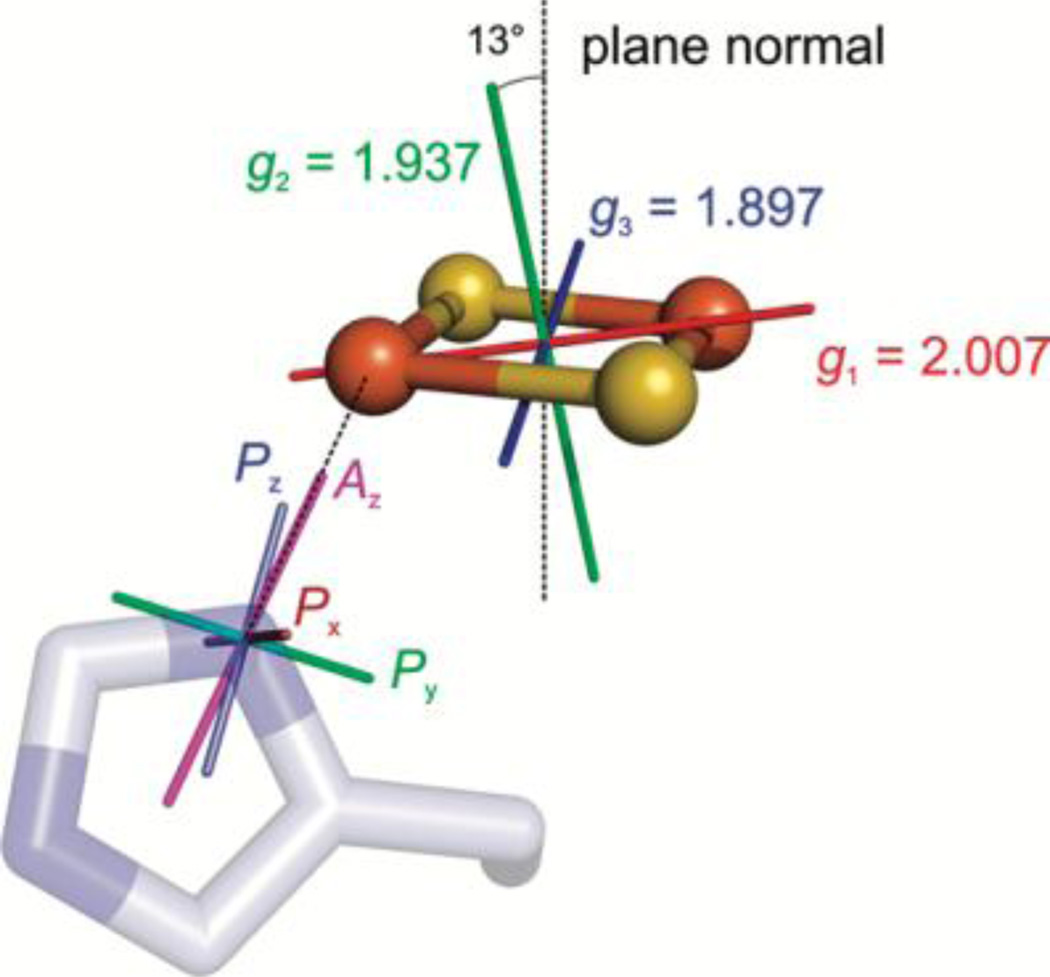

The 14N hyperfine parameters are scaled from the 15N ESEEM analysis by their nuclear gyromagnetic ratio |A(14N)/A(15N)| = |gn(14N)/gn(15N)| = 0.713, which then facilitates extraction of the 14N quadrupole parameters. The complete 14N quadrupole tensor, P(14N) and its relative orientation with respect to the iron sulfur cluster could then be elucidated by extensive analysis involving field dependent simulations and crystal structure information. From the simulation-determined P and A orientations with respect to g, assuming a typical quadrupole tensor orientation for the imidazole nitrogen, [24] the orientation of g was mapped on the cluster with its principal component, g1, lying in the Fe-(μ)S2-Fe plane, offset 33° from the Fe-Fe vector, Figure 15. This assignment for mitoNEET is in partial agreement with that of the original Rieske protein studies, where g1 was also assigned along the Fe-Fe vector. [79] It also only partially agrees with the later study on Rieske protein of bovine mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex by Bowman, et al., [149] who had available a protein crystal. Single crystal EPR has the ability to definitively map a g tensor onto the molecular frame. The Rieske bishistidine ligated [2Fe2S] core in the single-crystal case was found to have g1 close to the S-S vector. [149] Ultimately, single crystal EPR would need to be done on mitoNEET along with further examples of Rieske clusters to determine g tensor orientations overall in these systems. Such information would greatly assist computational studies of electronic structure of [2Fe2S] centers and how changes in coordination can tune the redox and catalytic properties of these important systems.

Figure 15.

The assignment shown of Az aligned with the N-Fe bond and Px with the imidazole plane normal yields the g tensor orientation for mitoNEET protein (g = [g1, g2, g3] = [2.007, 1.937, 1.897]). The angle between the g2 axis and the cluster plane normal is 13°, the g1 axis is 34° offset from the Fe-Fe vector, and g3 is 33° offset from the S-S vector. Reprinted with permission from Dicus, et al. [78] Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

Biotin Synthase

The biotin synthase enzyme (BS, or BioB) contains two FeS clusters. One is a [4Fe4S] cluster which binds S-adenosylmethionine (SAM or AdoMet) as observed by crystallography [155] and catalyzes the production of 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dA•) as performed by the radical SAM enzyme family, to be discussed later. The [4Fe4S] radical SAM cluster is not air-stable and is lost within minutes upon exposure to air and is thus absent from protein purified aerobically. A second single air-stable [2Fe2S]2+ cluster is observed per monomer of the biotin synthase homodimer isolated and purified from E. coli. [153]

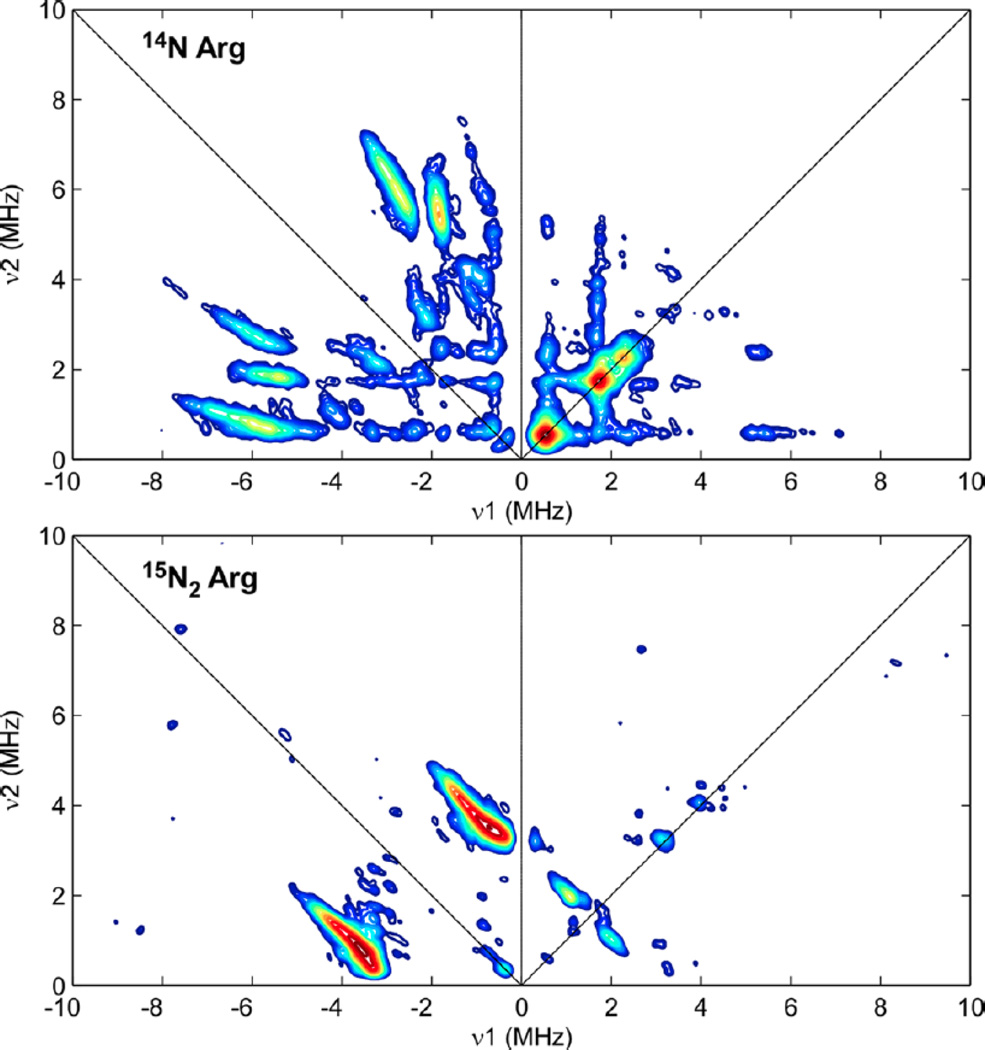

Isotopic 15N labeling of the Arg amino acids through the incorporation of (guanidino-15N2)-l-arginine into the growth media confirms the ligation of the paramagnetic [2Fe2S]+ cluster by the amino group of Arg260 (see Figure 13) and is supported by the previous loss of 14N hyperfine coupling observed for the Arg260Met variant by previous 3-pulse ESEEM spectroscopy and more recent 14/15N HYSCORE studies (Figure 16). [153, 156] This unique Arg ligation to a [2Fe2S]+ cluster, also observed in the crystal structure, [155] introduces another [2Fe2S]+ cluster with non-cysteine coordination.

Figure 16.

X-band HYSCORE spectra of biotin synthase paramagnetic intermediate grown in E. coli with natural abundance arginine (top) and (guanidino-15N2)-l-arginine (bottom). The 15N coupling observed in the bottom HYSCORE spectrum corresponds to 15N labeling of the Arg260 residue. Reprinted with permission from Fugate, et al. [153] Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

Spectroscopy of Substrates

The [4Fe4S] clusters serve many functions in Nature. Initially characterized solely as electron transfer agents, as in ferredoxins and other redox enzymes, their roles quickly expanded upon the discovery of the unique open iron site of the [4Fe4S] cluster of aconitase. [160] Beinert and Kennedy [137, 161–163] were the first to characterize an FeS cluster that catalyzed a chemical reaction, not just electron transfer. This section focuses on advanced EPR studies of exogenous compounds: substrates, substrate analogs, or inhibitors, which interact with the FeS cluster active site of such enzymes, and either have naturally occurring magnetic nuclei (1H, 14N, 31P) or can be specifically labeled with them (2H, 13C, 15N).

Aconitase

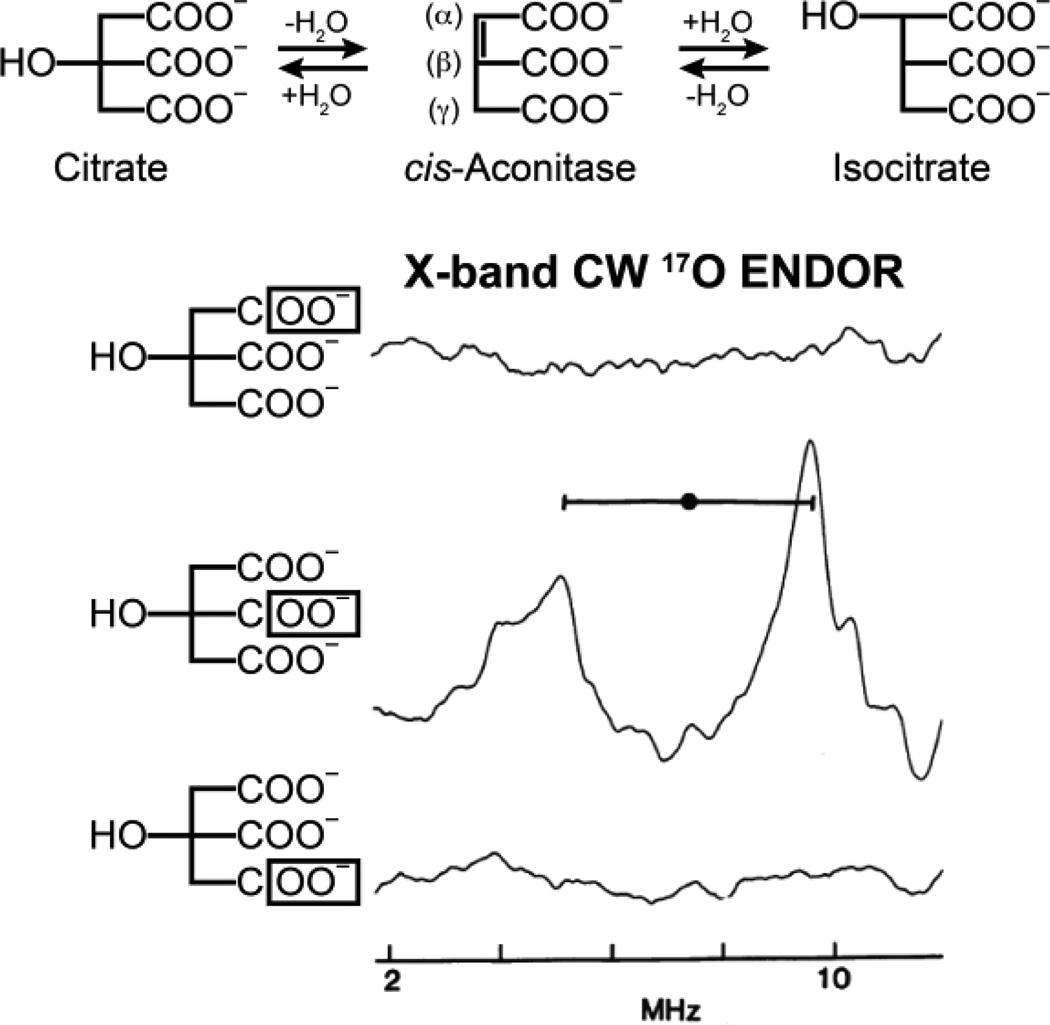

The enzyme aconitase catalyzes the stereospecific interconversion of citrate and isocitrate via the dehydrated intermediate cis-aconitate, Figure 17. The active site contains a [4Fe4S]2+ cluster that can be reduced to the EPR-active [4Fe4S]+ state with retention of activity. The cluster does not act in electron transport but rather performs its catalytic function through interaction with substrate at a specific single iron site of the cluster (Fea), first identified by Mössbauer. [164] This enzyme was the test bench whose study not only showed how ENDOR spectroscopy could determine active-site composition and electronic and geometric structure: ENDOR studies of substrate interactions made decisive contributions to the determination of the enzyme catalytic mechanism.

Figure 17.

X-band 17O CW ENDOR of isotopically labeled substrate at the α, β, and γ carboxyl positions as indicated in the figure. A 17O ENDOR response is only observed with labeling of the β carboxyl group. ENDOR spectra reprinted from Kennedy, et al. [162].

The first question addressed in the ENDOR investigation of the catalytic role of the cluster in a dehydration/hydration reaction was whether solvent HxO (H2O or OH−) and/or the OH of substrate binds to the cluster. The use of 17O, 1H, and 2H ENDOR showed that the fourth ligand of Fea in substrate-free enzyme is a hydroxyl ion from solvent, and that binding of substrate or substrate analogues to Fea causes the hydroxyl to become protonated to form a bound water molecule. Note that this represented the first demonstration of an exogenous ligand bound to an iron-sulfur cluster. The studies further suggested that the cluster might simultaneously coordinate the OH of substrate and H2O of the solvent (Figure 17).

The second key question was whether one or more carboxylate groups of substrate bind to the cluster. This was answered through the use of 17O ENDOR spectroscopy in conjunction with the biochemical brilliance of Beinert and Kennedy. Figure 17 presents ENDOR spectra of [4Fe4S]+ aconitase in the presence of three citrate isotopologues in which the three carboxyl groups have been individually labeled with 17O. ENDOR measurements with substrate whose central (β) carboxyl group is 17O labeled show a strong 17O pattern but no 17O ENDOR signal was observed when either of the terminal carboxyl groups (α or γ) was 17O labeled (Figure 17). Thus under the experimental conditions of these samples, the central carboxyl group binds to Fea, but the two terminal groups (α or γ) do not bind to the cluster. The end result of these and other 17O ENDOR measurements was that the substrate is bound as a chelate involving the citrate hydroxyl and a β-carboxyl oxygen, Figure 12. This ENDOR-derived structure for the substrate-bound cluster was eventually corroborated by subsequent X-ray diffraction studies. [165]

However, the enzyme also is able to accommodate substrate bound by the α-carboxyl, as was shown by 17O ENDOR of enzyme that had bound a 17O -enriched isocitrate analogue that lacks the β-carboxylate. Presumably the addition of the negatively charged carboxyl causes protonation of the OH- that binds to the cluster in the absence of substrate. The resulting structure of citrate bound to the unique Fe of the cluster, as deduced from ENDOR spectroscopy, is shown in Figure 12.

ENDOR spectroscopy thus showed that the cluster functions as follows: (i) it helps to position the substrate through the binding of one carboxyl; (ii) it coordinates and accepts the hydroxyl of substrate during the dehydration of citrate and isocitrate; (iii) it donates a bound hydroxyl during the rehydration of cis-aconitate. To accommodate the stereochemistry of the reaction, cis-aconitate must furthermore disengage from the active site, rotate 180°, and switch the carboxyl that binds before completing the catalytic cycle.

Nitrogenase

The mechanism of nitrogenase has been probed by ENDOR of numerous isotopically labeled substrates. [61, 166, 167] A detailed discussion of this aspect of the use of ENDOR is beyond the scope of this review, but has been recently summarized elsewhere. [58–60, 168]

Radical SAM

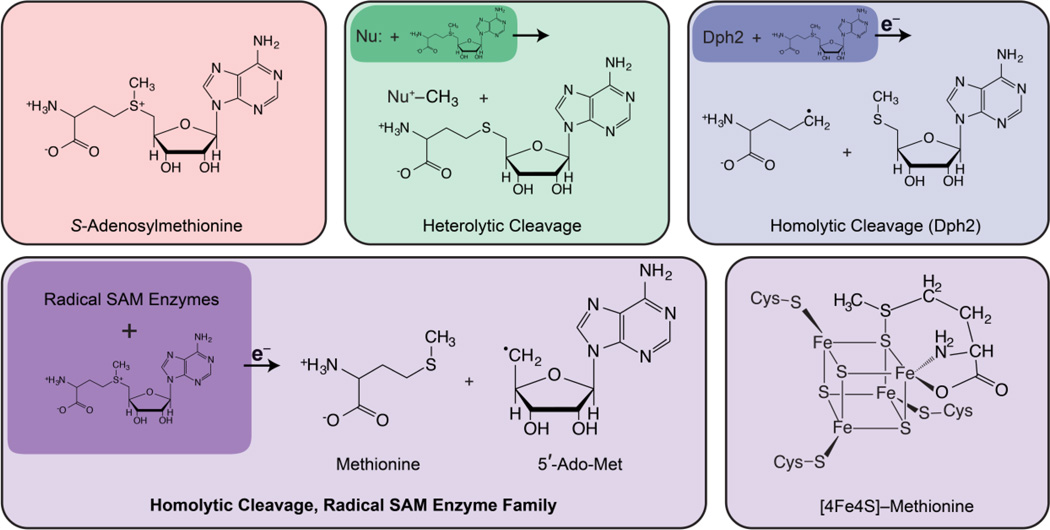

Following aconitase, other catalytic [4Fe4S] clusters have been discovered, [171] leading to a renaissance of interest in FeS proteins. The realization that the role of [4Fe4S] clusters extends beyond electron transfer has been greatly magnified by the discovery of their role in the radical SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) enzymes. Radical SAM enzymes comprise a diverse and rapidly expanding superfamily that has been recently reviewed (many times) [121, 172–176] [177–179] [180] and is the subject of other contributions to this volume (References This Issue).

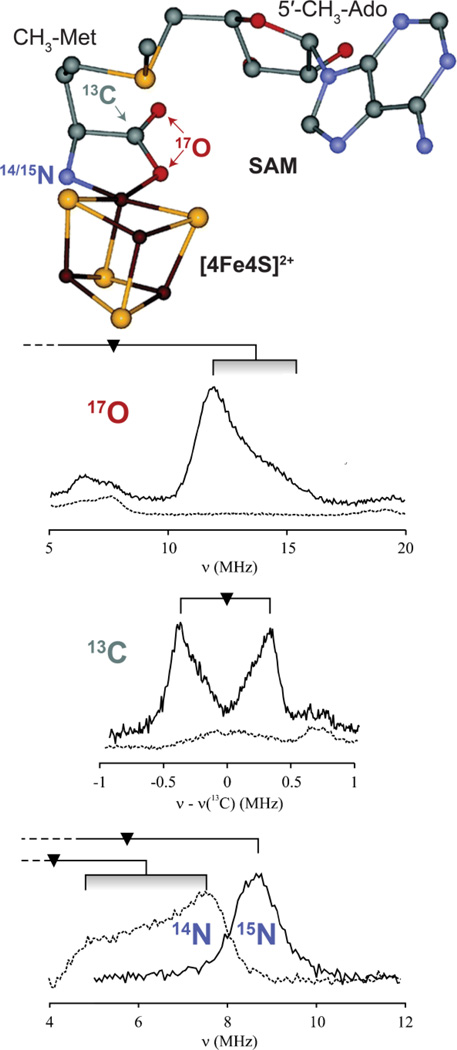

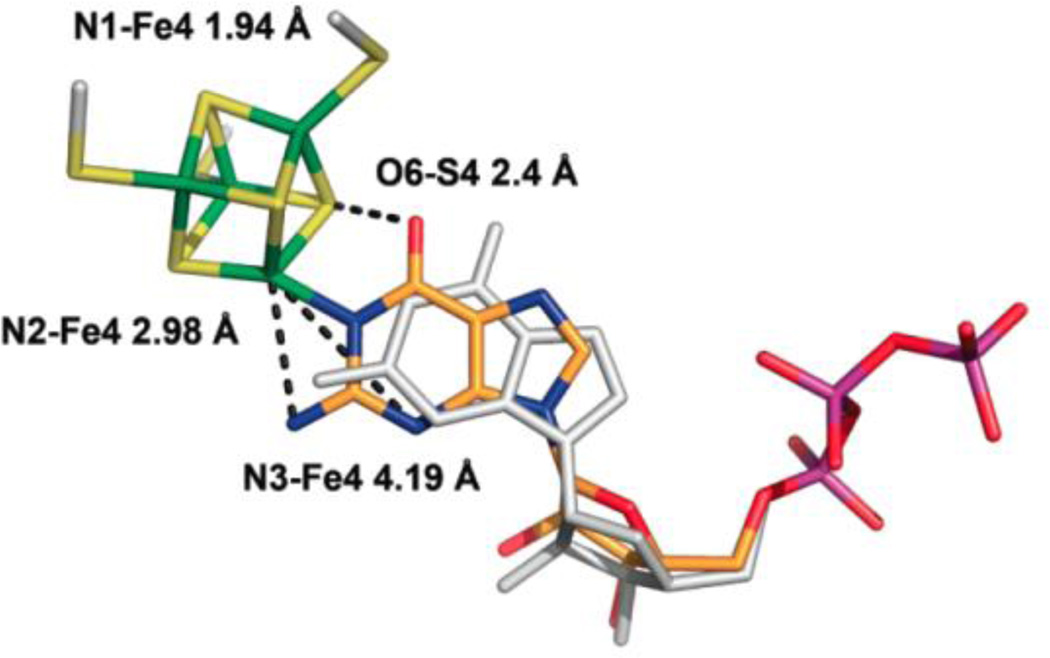

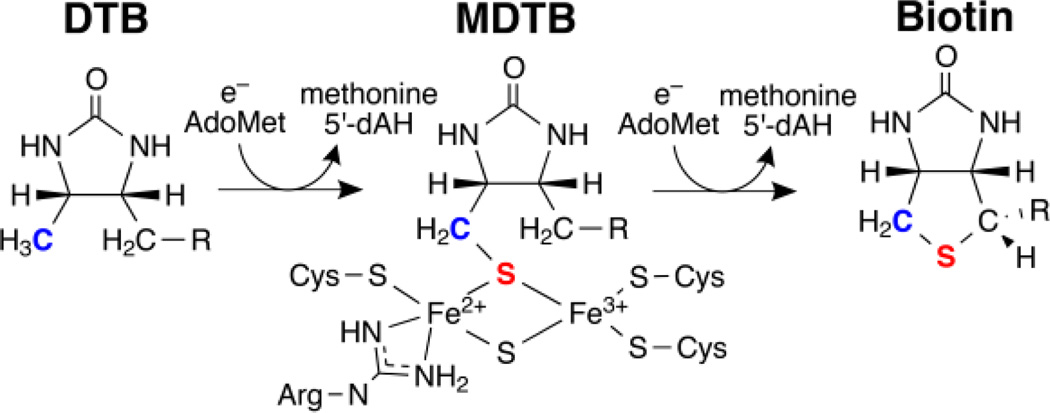

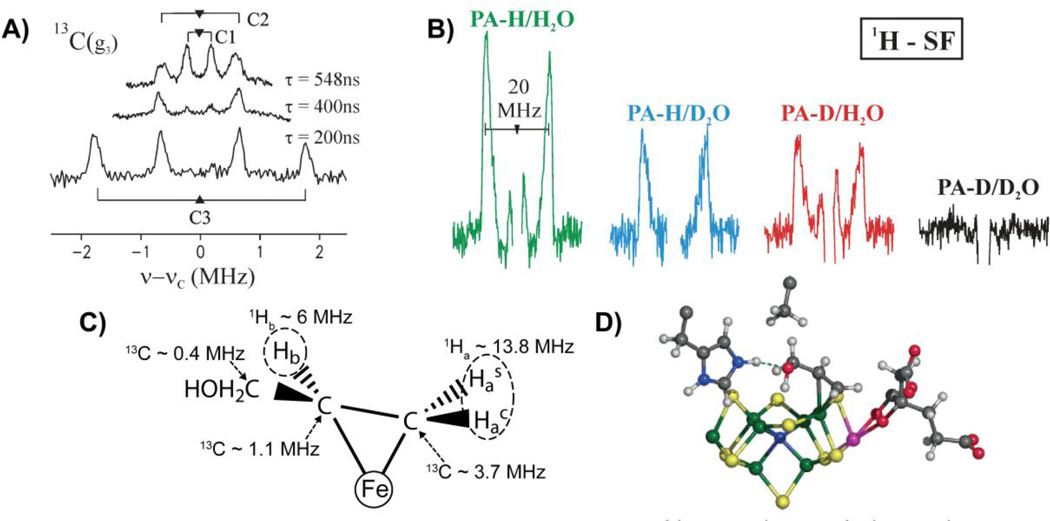

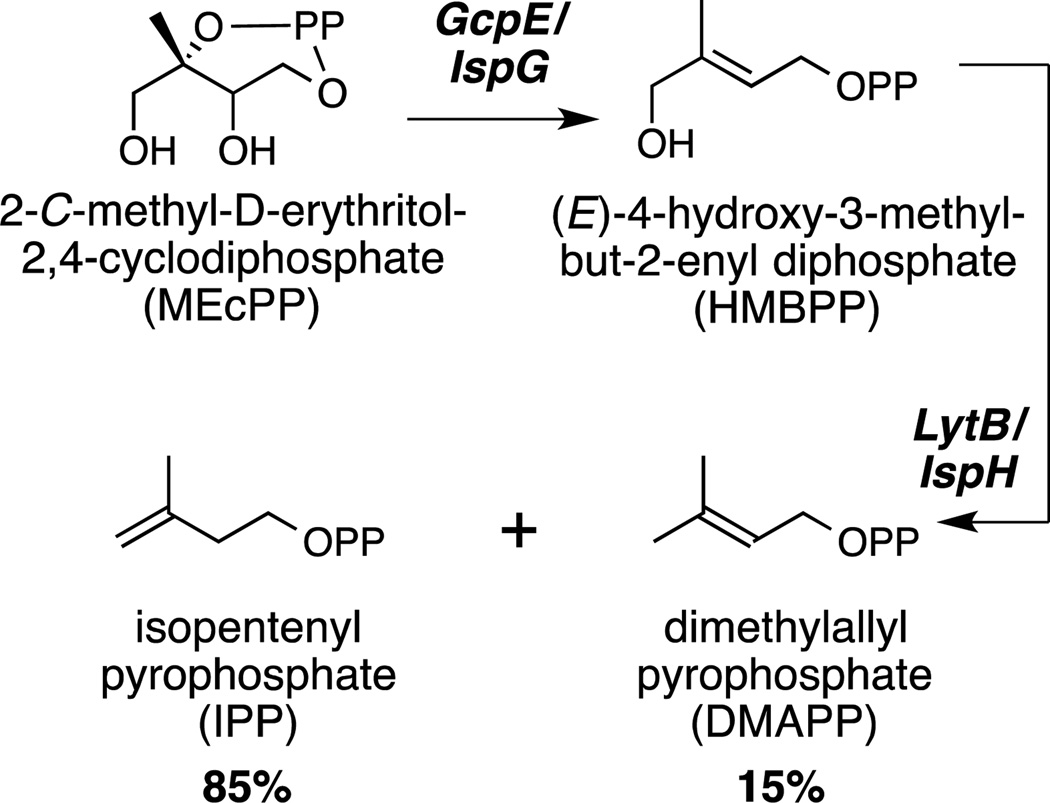

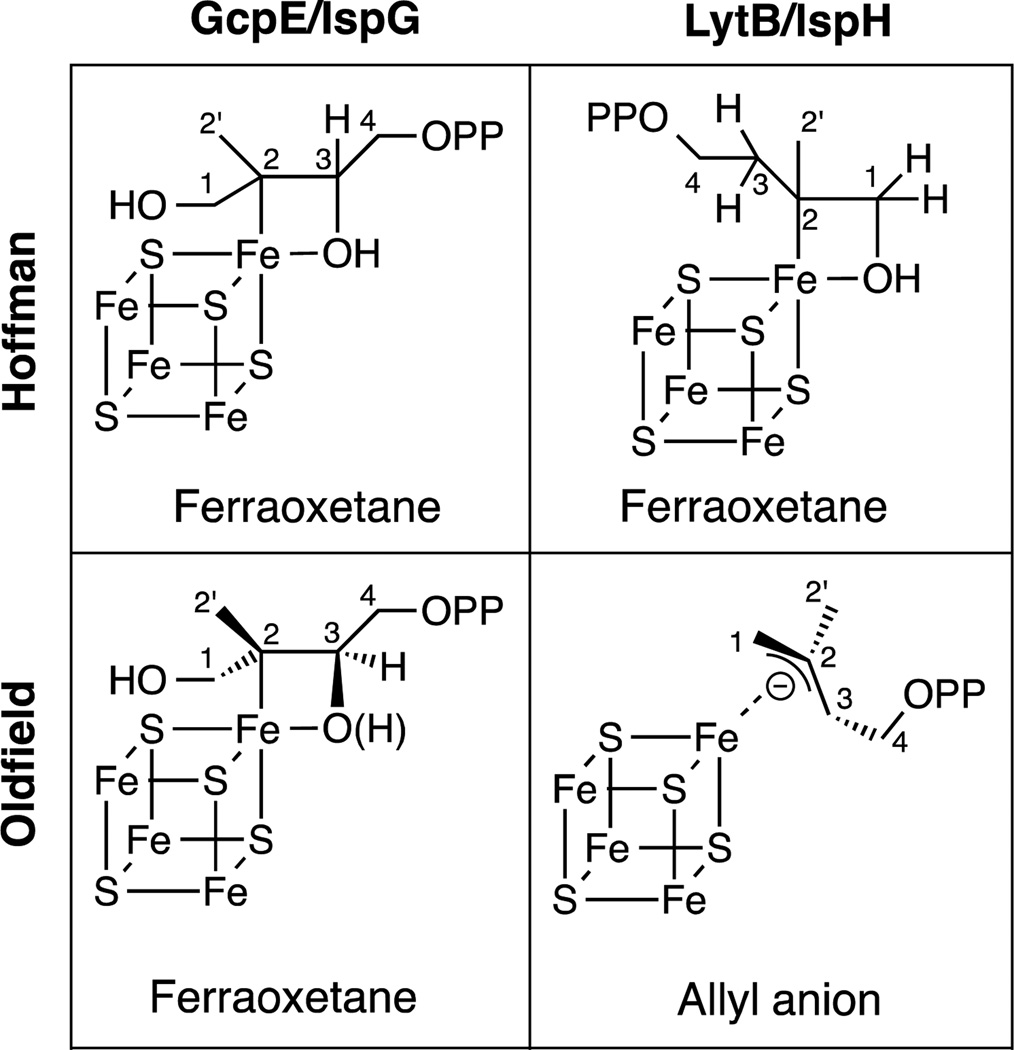

Enzymes of the radical SAM superfamily utilize a [4Fe–4S] cluster and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to generate catalytically essential radicals, Figure 18. A key mechanistic question posed by this family was the role of the [4Fe–4S] cluster bound by a characteristic CX3CX2C motif. As with aconitase, the clusters of these enzymes have a “unique” iron site that is not coordinated to the enzyme by a cysteinyl sulfur: does this Fe have a catalytic function, as is true for aconitase? This question was answered through the use of EPR and pulsed 35 GHz ENDOR spectroscopy applied to the radical-SAM enzymes, pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL) activating enzyme (PFL-AE), and lysine 2–3 aminomutase (LAM). [170, 181, 182] The experiments disclosed that the cluster plays at least a dual role: the unique Fe anchors the AdoMet cofactor by chelating the amino and carboxyl groups of methionine; electron transfer from the cluster initiates homolytic cleavage of the bond to adenosine.

Figure 18.