Abstract

Objectives

Saphenous nerve injury is the most common complication after surgical treatment of varicose veins. The aim of this study was to establish its frequency at great saphenous vein long stripping when four methods of surgery were applied.

Methods

Eighty patients were divided into four groups depending on different stripping methods. Sensory transmission in saphenous nerve and sensory perception of shank were examined before surgery and two weeks, three and six months afterwards with clinical neurophysiology methods.

Results

In 36% of patients, surgeries caused the injury of saphenous nerve mainly by proximal stripping without invagination (65%, group I). Transmission disturbances ceased completely after three months in patients undergoing distal stripping with invagination (group IV), while in group I they persisted for six months in 35%. Group IV patients were the least injured and group I the most.

Conclusion

Neurophysiological findings may suggest that distal stripping with vein invagination gives the best saphenous nerve sparing.

Keywords: Great saphenous vein stripping, saphenous nerve sensory transmission, neurophysiological examinations

Introduction

Varicose veins surgery is one of the most frequent operations carried out in Europe as well as one of the most frequent causes of civil-law proceedings against general and vascular surgeons, especially in West European countries, which results mainly from incidental nerve injury.1,2 The increase in medical claims forces a search for the method of varicose veins treatment that can guarantee the fewest complications possible.

The fundamental approach in surgical treatment of varicose veins with great saphenous vein incompetence is the long stripping.3–5 There are several variants of the method: proximal stripping with a probe – the classical Babcock method, proximal stripping with invagination (inversion) of the vessel, distal stripping with and without invagination.6–10

The varicose veins extraction may be associated with many intra- and postsurgical complications. However, the most frequent is the saphenous nerve lesion, which is related to its anatomical path. Possible anomalies in the common anatomical passage of the saphenous nerve to the great saphenous vein should be considered during varicose veins extraction and what can foster iatrogenic injuries within higher risk zones.11

Femoral and crural portions can be distinguished in the course of saphenous nerve. The nerve runs subfascially within the femoral portion, whereas within the crural portion it pierces the crural fascia and, running epifascially together with the great saphenous vein, reaches the medial margin of the foot. The nerve supplies sensory innervation to the medial side of the lower thigh, anteromedial side of the knee joint and the leg down to medial side of the foot and hallux. During stripping of the great saphenous vein, a lesion most frequently affects the nerve trunk in region of medial malleolus and its subpatellar branch together with the medial cutaneous branches of the leg, which manifests as inaccurate feeling perception (paresthesia) in the form of tingling, numbness, electric current sensation, hypoesthesia, hyperesthesia, or a burning sensation.

The aims of this study were to establish and objectivise the relation between saphenous nerve conduction disorders and varicose vein surgery as well as to compare the frequency of nerve injury in the four methods of great saphenous vein stripping.

Methods

A group of 80 patients with confirmed venous incompetence of Hach’s III and IV class by clinical (according to CEAP classification – C2 grade) and imaging (Doppler ultrasonography) examinations was enrolled into this neurophysiological prospectively gathered data.12 Patients did not report the neuropathic pain before surgery, the supplemental management with pregabalin and methylcobalamin was not applied. The patients were qualified for surgical treatment in Department of General and Vascular Surgery at Karol Marcinkowski Poznań University of Medical Sciences from 2004 to 2008 basing on the rule of consecutive cases. The neurophysiological examinations were conducted in Department of Pathophysiology of Locomotor Organs four times (before surgery-S1, two weeks after surgery-S2, three months after surgery-S3, and six months after surgery-S4).

Patients aged from 20 to 50 years (42.2 years on average) were randomly divided into four subgroups (20 persons each) G1–G4 depending on the different stripping methods (G1-group after proximal stripping without invagination, G2-group after proximal stripping with invagination, G3-group after distal stripping without invagination, G4-group after distal stripping with invagination). The length of great saphenous vein stripping depended on the type of surgery. In each group, the same female to male proportion was maintained (15 females and five males). Each subgroup was operated with different stripping method. The saphenous nerve was not identified along the saphenous vein at the knee and it was not separated from it before stripping. Patients suffering from conditions that possibly affect nervous system functions, which could be polyneuropathies, multiple peripheral mononeuropathies, demyelinating diseases, neuromuscular diseases, deficiency syndromes, nervous system poisoning, advanced discopathy, extremity or vertebral column trauma, arterial diseases, episodes of superficial vein thrombosis, post-thrombotic syndrome were excluded from this study.

The general methodology was based on neurophysiological examinations of saphenous nerve conduction.13–16 It was carried out four times. First time it was before the operation, in order to estimate preliminary values of neurophysiological variables (amplitude, latency, conduction velocity) in sensory conduction studies (SCV), then two weeks after the operation to establish a possible nerve injury due to surgical intervention, three months after the operation when the changes affecting conduction (swellings, hematomas, rubber bandage wearing) had disappeared and six months after the operation to assess the improvement of neurophysiological parameters in the patients with previously detected conduction disorders. The results were analyzed with reference to the control group of 50 healthy volunteers (40 females and 10 males aged 45.1 years on average) recruited from hospital workers whom the SCV reference values were acquired.

The neurophysiological testing was performed with Keypoint System (Medtronic A/S, Skovlunde, Denmark). Evoked potentials were recorded at different levels of saphenous nerve conduction with standard silver chloride electrodes, using two techniques of saphenous nerve examination (distal and proximal). In the distal method, recording took place anterior to medial malleolus and stimulation 14 cm, 18 cm, 22 cm, 26 cm above, along the medial margin of tibia. In the proximal method, potentials were recorded at the midpoint between medial malleolus and the slot of the knee joint along the medial margin of tibia while stimulation was performed 14 cm, 18 cm, and 22 cm above. The ground electrode was placed halfway between the recording and stimulating electrodes. Bilateral and bipolar saphenous nerve stimulation was performed, applying supramaximal, rectangular, single electric stimuli with a frequency lower than 3 Hz, 0.2 ms duration and intensity up to 30 mA. The recordings were carried out with time base usually 2 ms, amplification 5 µV, high-pass filter at 5 Hz and low-pass filter at 3 kHz. The parameters of amplitude, latency and corresponding afferent conduction velocities were evaluated. Amplitude greater than 1 µV was considered as normal. The conduction velocity depended on the distance at which the saphenous nerve was examined. The following minimal conduction velocities were accepted: 140 mm – 38.58 m/s; 180 mm – 39.13 m/s; 220 mm – 39.85 m/s; 260 mm – 40.21 m/s for distal and 140 mm – 40.53 m/s; 180 mm – 40.86 m/s; 220 mm – 41.38 m/s for proximal method.

Two methods complementary to SCV studies were used in order to study the saphenous nerve sensory function. First, it was the intensity of current versus stimulus duration curves (IC–SD) that was conducted after monopolar stimulation of skin anterior to the medial malleolus, then 14 cm and 26 cm. Second, it was the von Frey’s filaments examination (FvF) in three areas, the medial part of popliteal region, the middle 1/3 of the leg on the medial side and medial malleolus region. During each FvF examination, three measurements were performed with calibrated silicon filaments: 0.12 mm, 0.30 mm (corresponding to proper sensory perception), and 0.55 mm in diameter. Touch sensation reported in two out of three assessments was considered as positive. A positive trial with the thinnest filament indicated hyperesthesia and the completely negative trial – analgesia.

The research was approved by The Bioethics Committee of Medical University in Poznań and it was performed with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Examined subjects gave their informed consent for the examinations. All subjects were informed about the aim of study and about the course of examination.

Statistics

In the statistical analysis of the obtained results, the Statistica programme 9.0 was used (StatSoft). The Fisher–Freeman–Halton test was used for evaluation of sample size during studies on normality distribution, similarly the McNemara when two measurements were compared (between groups) or the Cochran’s Q test when more than three measurements were considered (between stages of observations). The results were considered as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

There was no nerve transmission abnormalities detected prior to surgery in any group. Nerve transmission abnormalities diagnosed two weeks after the operation (in 30 out of 80 patients – 37.5%) were present in 17 cases (21.25%) after three months and in 11 patients (13.75%) after six months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number (percentage) of parameters changes in sensory fibers transmission of saphenous nerve (SCV studies) at four stages of observation (S1–S4) during recordings in patients from four groups with different stripping methods (G1-group after proximal stripping without invagination, G2-group after proximal stripping with invagination, G3-group after distal stripping without invagination, G4-group after distal stripping with invagination).

| Before surgery (S1) | Two weeks after surgery (S2) | Three months after surgery (S3) | Six months after surgery (S4) | Differences between stages of observation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N = 80 | 0/80 (0%) | 30/80 (37.5%) | 17/80 (21.25%) | 11/80 (13.75%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S1: S3 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S1: S4 = 0.0010 | |||||

| S2: S3 = 0.0008 | |||||

| S2: S4 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S3: S4 = 0.0412 | |||||

| G1, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 13/20 (65%) | 10/20 (50%) | 7/20 (35%) | S1: S2 = 0.0002 |

| S1: S3 = 0.0020 | |||||

| S1: S4 = 0.0156 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0412 | |||||

| G2, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 7/20 (35%) | 4/20 (20%) | 2/20 (10%) | S1: S2 = 0.0156 |

| G3, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 6/20 (30%) | 3/20 (15%) | 2/20 (10%) | S1: S2 = 0.0312 |

| G4, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 4/20 (20%) | 0/20 (0%) | 0/20 (0%) | |

| Differences between groups | G1:G4 = 0.0095 | G1:G3 = 0.0407 | G1:G4 = 0.0083 | ||

| G1:G4 = 0.0004 | |||||

Statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 are marked bold.

In three groups of patients (G1–G3), a statistically significant (p < 0.05) saphenous nerve lesion was identified two weeks after the surgery. In group G1 (proximal stripping without invagination), it occurred in 65%, in group G2 (proximal stripping with vein invagination) in 35%, and in group G3 (distal stripping without vein invagination) – in 30%. Best results of treatment were observed in group G4 (distal stripping with vein invagination) where no statistically significant consequences of nerve injury were detected. Six months after the operation sensory conduction disturbances were identified in a remarkable number of patients (seven out of 20 that is 35%) but only in group G1 (Table 1).

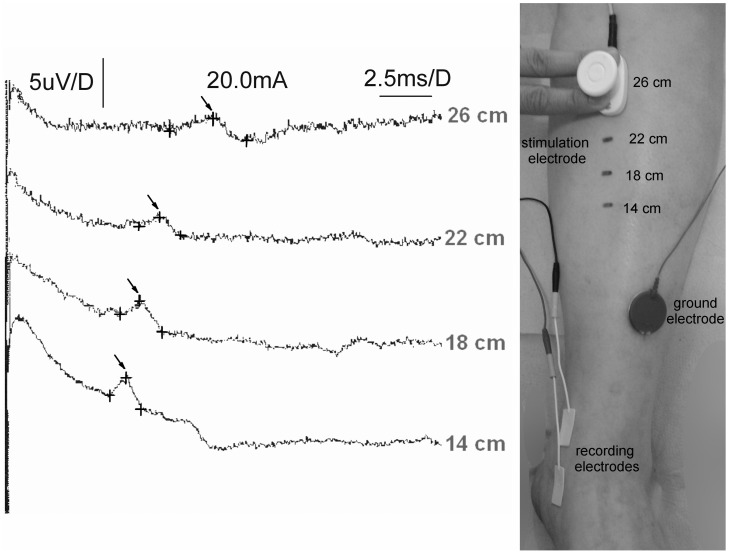

Among the patients with disturbances of nerve transmission in the saphenous nerve fibers, the most frequent observation was slowing down of the conduction velocity with proper amplitude parameters (Figure 1). The results of SCV indicating deficiencies in sensory transmission are related with the results of IC–SD as well as with the von Frey filaments examination, which are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Examples of neurophysiological SCV recordings from saphenous nerve following electrical stimulation at distances shown on the right part of figure. Recordings were obtained in one of the patients 3 months after proximal stripping without invagination. Calibrations for amplification (µV) and time base (ms) as well as intensity of stimulation (mA) are shown in upper part of figure. Note proper values of potentials amplitudes (marked with crosses) but their prolonged latencies (marked with arrows) influenced the conduction velocities of nerve impulses in sensory fibers.

Table 2.

Number (percentage) of changes in sensory perception (IC–SD studies) of saphenous innervation at four stages of observation (S1–S4) during recordings in patients from four groups with different stripping methods (G1-group after proximal stripping without invagination, G2-group after proximal stripping with invagination, G3-group after distal stripping without invagination, G4-group after distal stripping with invagination).

| Before surgery (S1) | Two weeks after surgery (S2) | Three months after surgery (S3) | Six months after surgery(S4) | Differences between stages of observation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N = 80 | 0/80 (0%) | 49/80 (61.25%) | 22/80 (27.5%) | 12/80 (15%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S1: S3 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S1: S4 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S2: S3 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0060 | |||||

| S3: S4 = 0.0040 | |||||

| G1, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 15/20 (75%) | 11/20 (55%) | 7/20 (35%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S1: S3 = 0.0009 | |||||

| S1: S4 = 0.0156 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0133 | |||||

| G2, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 14/20 (70%) | 5/20 (25%) | 2/20 (10%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S2: S3 = 0.0076 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0015 | |||||

| G3, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 11/20 (55%) | 4/20 (20%) | 2/20 (10%) | S1: S2 = 0.0010 |

| S2: S3 = 0.0233 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0076 | |||||

| G4, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 9/20 (45%) | 2/20 (10%) | 1/20 (5%) | S1:S2 = 0.0039 |

| S2:S3 = 0.0233 | |||||

| S2:S4 = 0.0133 | |||||

| Differences between groups | G1:G3 = 0.0483 | G1:G4 = 0.0436 | |||

| G1:G4 = 0.0054 | |||||

Statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 are marked bold.

Table 3.

Number (percentage) of sensory perception disturbances (von Frey filaments examination) for saphenous innervation at four stages of observation (S1–S4) during recordings in patients from four groups with different stripping methods (G1-group after proximal stripping without invagination, G2-group after proximal stripping with invagination, G3-group after distal stripping without invagination, G4-group after distal stripping with invagination).

| Before surgery (S1) | Two weeks after surgery (S2) | Three months after surgery (S3) | Six months after surgery (S4) | Differences between stages of observation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N = 80 | 0/80 (0%) | 38/80 (47.5%) | 24/80 (30%) | 15/80 (18.75%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S1: S3 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S1: S4 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S2: S3 = 0.0005 | |||||

| S2: S4 < 0.0001 | |||||

| S3: S4 = 0.0076 | |||||

| G1, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 15/20 (75%) | 12/20 (60%) | 9/20 (45%) | S1: S2 < 0.0001 |

| S1: S3 = 0.0005 | |||||

| S1: S4 = 0.0039 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0412 | |||||

| G2, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 10/20 (50%) | 4/20 (20%) | 2/20 (10%) | S1: S2 = 0.0020 |

| S2: S3 = 0.0412 | |||||

| S2: S4 = 0.0133 | |||||

| G3, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 6/20 (30%) | 5/20 (25%) | 3/20 (15%) | S1: S2 = 0.0316 |

| G4, N = 20 | 0/20 (0%) | 7/20 (35%) | 3/20 (15%) | 1/20 (5%) | S1:S2 = 0.0156 |

| S2:S4 = 0.0412 | |||||

| Differences between groups | G1:G3 = 0.0103 | G1:G2 = 0.0224 | G1:G2 = 0.0309 | ||

| G1:G4 = 0.0248 | G1:G4 = 0.0007 | G1:G4 = 0.0084 | |||

Statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 are marked bold.

In postoperative observations, the significant saphenous nerve sensory perception abnormalities were detected in each group of patients based on results of IC–SD and von Frey filaments studies. Three and six months after the varicose veins extractions there was detected similar, moderate improvement of sensory perception parameters in groups G2 and G3. The best results of saphenous nerve regeneration were observed in G4 (one out of 20 patients – 5% in both IC–SD and FvF studies) and the worst in G1 (seven out of 20 patients – 35% in IC–SD examinations and nine out of 20 patients – 45% in FvF studies) groups.

Discussion

Saphenous nerve injury is known for a long time to be a potential complication of the saphenous vein long stripping.6–10,13–24 The proximity of the vein and nerve, especially at the level of shank, results in injuries during the vein resection,25–29 especially in the patients with advanced varicose veins in this area caused by a large number of insufficient perforators. Additionally, in the patients suffering from long-lasting varicose veins, it can lead to an accretion of the widened-vein, providing the saphenous nerve neuropraxy. This pathology also facilitates in injury of the nerve fibers during the operation. The sensory disorders associated with an injury to the nerve trunk or its branches, occurring after the varicose veins surgical treatment, can be either temporary or constant.23,26

The results presented in this paper, referring to the saphenous nerve injury during the varicose veins surgical treatment using the saphenous vein long stripping, correlate with the results that are to be found in publications devoted to the subject.18,19,21 Many authors tried to determine the frequency of this complication. It varies from 5.9% to 72% and depends to a large extent on the applied stripping technique.17–19,21,23–26

In the study presented, the most numerous saphenous nerve injuries were identified after the proximal long stripping without vein invagination (the Babcock method). Such complications were reported in 20–50% of patients treated with classical stripping of the Babock type.27 It is joined to the anatomical relation of the saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve together with its divisions. Anatomically, the nerve branches form a reverted V shape, which facilitates their injury by the probe’s head, especially while proximal pulling of the vein.17,18,28

Invagination of the vein as well as the change in the direction of its removal from proximal to distal caused the reduction in the number of neurological complications related to the saphenous nerve injury.8,19 The proximal stripping with invagination of the vessel and the distal stripping without invagination occurred to be comparable in terms of the number of postsurgical sensory disorders in the saphenous nerve innervation area.

The best effects were achieved with distal stripping with vein invagination.19 From the results of this study, it can be concluded that this method is the least invasive for the saphenous nerve. All the conduction abnormalities that were objectively identified in SCV studies two weeks after the surgery were temporary and normalized at three months after the operation. Part of the patients subjectively still suffered from some sensory disorders, which was confirmed in FvF and IC–SD examinations perhaps due to the injury in small branches of saphenous nerve. Based on the results of neurophysiological findings provided in this study, we suppose that compilation of distal stripping with vein invagination gives the best saphenous nerve sparing during varicose veins extraction. Transient changes in nerve transmission observed two weeks after surgery can be due to the temporary neuropraxia caused by edema, hematoma, inflammatory processes, or simply by the mechanical irritation during operation.

A large number of neurological complications after the varicose veins surgery in lower extremities with the use of the saphenous vein stripping make alternative means of treatment of the saphenous vein incompetency worth consideration.30–34

One of these alternative methods is the short stripping to the level of knee joint with additional phlebectomy of the varicose veins below this level.24

It should be remembered, however, that in spite of more and more innovative methods of the varicose veins treatment, the long stripping is still the most common procedure and a first-choice therapy for the saphenous vein incompetence.3–5 Even if the sensory disorders developed after the surgical removal of the whole vein can persist in some patients, the advantages of varicose veins resection much exceed the inconveniences resulting from the potential neurological complications. Nerve injuries also might appear after thermal ablation associated with varicose veins surgeries and there is a need for a similar like presented study of patients having various endovenous treatments. The limited size of this study seems to be a weakness of the presented report, but its results may suggest that neurophysiological testing is valuable for evaluation of the treatment efficiency after varicose veins surgeries.

Conclusions

Varicose veins surgery in the lower limbs using the technique of the saphenous vein long stripping significantly impacts the sensory conduction in the saphenous nerve. Distal stripping with vein invagination seems to be the least invasive for the saphenous nerve fibers, which may be a consequence of the anatomical relation of the saphenous nerve and vein. Proximal stripping without vein invagination leads to the most numerous neurological complications detected two weeks after the operation as well as three and six months after the procedure, when the changes possibly affecting the nerve transmission had ceased.

Conflict of interest

All the authors have no conflict of interest and nothing to disclose.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Sam RC, Silverman S, Bradbury AW. Nerve injuries in varicose vein surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004; 2: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Alvarenga Yoshida R, Yoshida WB, Sardenberg T, et al. Fibular nerve injury after small saphenous vein surgery. Ann Vasc Surg 2012; 26: 729.e11–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michaels JA, Brazier JE, Campbell WB, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg 2005; 93: 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rollo HA. Varicose vein surgery with preservation of the great saphenous vein: assessment of long-term results in patients treated by flush ligation of the saphenofemoral junction. J Vasc Bras 2008; 7: 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winterborn RJ, Earnshaw JJ. Crossectomy and great saphenous vein stripping. J Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 47: 19–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheltinga MR, Wijburg ER, Keulers BJ, et al. Conventional versus invaginated stripping of the great saphenous vein: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. World J Surg 2007; 31: 2236–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacroix H, Nevelsteen A, Suy R. Invaginating versus classic stripping of the long saphenous vein. A randomized prospective study. Acta Chir Belg 1999; 99: 22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goren G, Yellin AE. Minimally invasive surgery for primary varicose veins: limited invaginal axial stripping and tributary (hook) stab avulsion. Ann Vasc Surg 1995; 9: 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler CM, Coleridge Smith PD, Scurr JH. Inverting stripping versus conventional stripping of the long saphenous vein. Phlebology 1995; 10: 128–128. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent PJ, Maughan J, Burniston M, et al. Perforation-invagination (PIN) stripping of the long saphenous vein reduces thigh haematoma formation in varicose vein surgery. Phlebology 1999; 14: 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uhl JF, Gillot C. Anatomy and embryology of the small saphenous vein: nerve relationships and implications for treatment. Phlebology 2013; 28: 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eklof B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al. American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40: 1248–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DJ, De Lisa JA. Manual of nerve conduction study and surface anatomy for needle electromyography, Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura I, Ayyar DR, McVeety JC. Saphenous nerve conduction in healthy subjects. Tohoku J Exp Med 1983; 140: 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stohr M, Shumm F, Ballier R. Normal sensory conduction in the saphenous nerve in man. EEG Ciln Neurophysiol 1978; 44: 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senden R, Van Mulders J, Ghys R, et al. Conduction velocity of the distal segment of the saphenous nerve on normal adult subject. EEG Clin Neurophysiol 1987; 21: 3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramasatry SS, Dick GO, Futrell WJ. Anatomy of the saphenous nerve: relevance to saphenous vein stripping. Am Surg 1987; 53: 274–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison C, Dansing MC. Signs and symptoms of saphenous nerve injury after greater saphenous vein stripping: prevalence, severity and relevance for modern practice. J Vasc Surg 2003; 38: 886–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorrentino P, Renier M, Coppa F, et al. How to prevent saphenous nerve injury. A personal modified technique for stripping of the long saphenous vein. Minerva Chir 2003; 58: 123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcucci G, Accrocca F, Antonelli R, et al. The management of arterial and venous injury during saphenous vein surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008; 7: 432–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frings N, Glowacki P, Kohajda J. Major vascular and neural complications in varicose vein surgery. Prospective documentation of complication rate in surgery of the V. saphena magna and V. saphena parva. Chirurg 2001; 72: 1032–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mildner A, Hilbe G. Complications in surgery of varicose veins. Zentralbl Chir 2001; 126: 543–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negus D. Complications of superficial venous surgery: nerve lesions in the leg and the popliteal fossa. Phlebologie 1993; 46: 601–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holme JB, Skajaa K, Holme K. Incidence of lesions of the saphenous nerve after partial or complete stripping of the long saphenous vein. Acta Chir Scand 1990; 156: 145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox JS, Wellwood JM, Martin A. Saphenous nerve injury caused by stripping of the long saphenous vein. Br Med J 1974; 1: 415–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almazan Enriquez A, Ramos Boyero M, Salvador Fernandez L. Neuropathic syndromes after varicose vein surgery of the lower limbs. Angiologia 1981; 33: 79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fullarton GM, Calvert MH. Intraluminal long saphenous vein stripping: a new technique minimizing perivenous tissue trauma. Br J Surg 1987; 74: 255–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holme JB, Holme K, Sorensen LS. The anatomic relationship between the long saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve. Relevance for radical varicose vein surgery. Acta Chir Scand 1988; 154: 631–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papakostas JC, Douitsis E, Sarmas I, et al. The impact of direction of great saphenous vein total stripping on saphenous nerve injury. Phlebology 2014; 29: 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aremu MA, Mahendran B, Butcher W, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial: conventional versus powered phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39: 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandler JG, Pichot O, Sessa C, et al. Treatment of primary venous insufficiency by endovenous saphenous vein obliteration. Vasc Surg 2000; 34: 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sybrandy JE, Wittens CHA. Initial experience in endovenous treatment of saphenous vein reflux. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36: 1207–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milone M, Salvatore G, Maietta P, et al. Recurrent varicose veins of the lower limbs after surgery. Role of surgical technique (stripping vs. CHIVA) and surgeon's experience. G Chir 2011; 32: 460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rautio T, Ohinmaa A, Perälä J, et al. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operation in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]