Abstract

Based on the scaffolds of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) as well as bioactive lactone-containing compounds, 6-acrylic phenethyl ester-2-pyranone derivatives were synthesized and evaluated against five tumor cell lines (HeLa, C6, MCF-7, A549, and HSC-2). Most of the new derivatives exhibited moderate to potent cytotoxic activity. Moreover, HeLa cell lines showed higher sensitivity to these compounds. Particularly, compound 5o showed potent cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 0.50 – 3.45 μM) against the five cell lines. Further investigation on the mechanism of action showed that 5o induced apoptosis, arrested the cell cycle at G2/M phases in HeLa cells, and inhibited migration through disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. In addition, ADME properties were also calculated in silico, and compound 5o showed good ADMET properties with good absorption, low hepatotoxicity, and good solubility, and thus, could easily be bound to carrier proteins, without inhibition of CYP2D6. A structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis indicated that compounds with ortho-substitution on the benzene ring exhibited obviously increased cytotoxic potency. This study indicated that compound 5o is a promising compound as an antitumor agent.

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem in many parts of the world, accounting for 23% of all deaths and the second only to heart diseases in 2014.1 Among various cancers, lung cancer is the most common cause of deaths, accounting for more than one-quarter of all cancer deaths in men and women. Other cancers, such as prostate in men and breast in women, are also very common causes of deaths from cancer.2

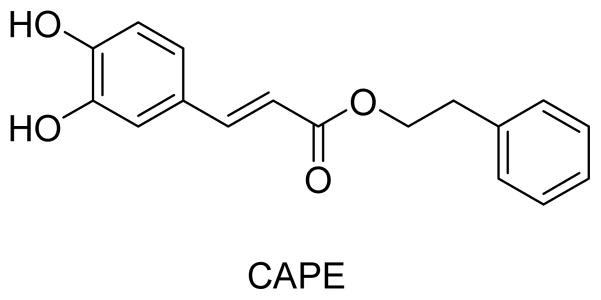

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) (Figure 1) is a main constituent of propolis, a resinous substance used in folk medicine for treating various ailments. CAPE was widely reported to possess anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, and antitumor activities.3 Moreover, CAPE selectively inhibited proliferation of several types of carcinoma cell lines, but showed almost no toxic effects on normal peripheral blood cells or normal hepatocytes. Some CAPE derivatives showed potent activity against lung cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma,4 uterine corpus cancer, breast cancer,5 glioma,6 leukemia,7 and oral cancer.8 Omene and co-authors9 also demonstrated that CAPE induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and inhibited angiogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of CAPE

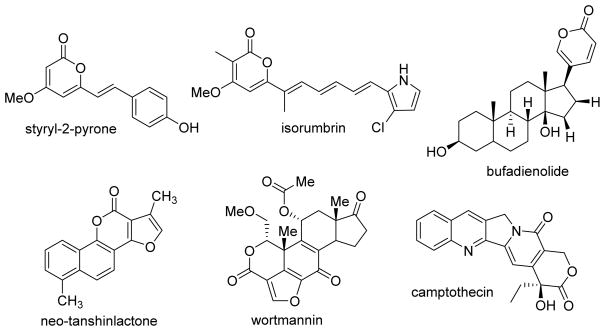

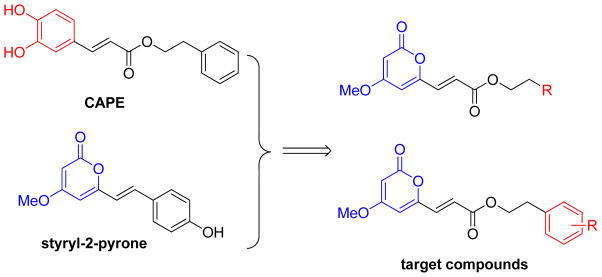

In our continuing studies to modify antitumor natural products for increased potency, we aimed to determine whether the catechol moiety is essential for the cytotoxic activity of CAPE and related derivatives. Our plan was to change the catechol ring to a lactone ring, specifically a 4-methoxy-2H-pyran-2-one. Lactone ring systems are found in many bioactive natural products obtained from plants, animals, marine organisms, bacteria, and insects,10 including those that exhibit various pharmacological activities, such as HIV protease inhibitory,11 anticonvulsant,12 antimicrobial,13 antitumor,14,15 and other effects. Examples include styryl-2-pyrone,16 isorumbrin,17 bufadienolide,18 neo-tanshinlactone,19 wortmannin,20 and camptothecin,21 as shown in Figure 2. Based on numerous modification studies, such as those performed on camptothecin and its derivatives, a lactone ring can be an important pharmacophore in anticancer drugs.22

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of several natural products with lactone rings

Therefore, based on the antitumor activity of CAPE and various lactone-containing compounds, we combined both CAPE and styryl-2-pyrone scaffolds as chemical starting points to design chemically modified CAPE analogues, which contain variously substituted acrylic phenethyl esters and a 4-methyoxy-2-pyranone moiety (Figure 3). Subsequently, 21 new CAPE derivatives were synthesized and evaluated against five tumor cell lines. Preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) correlations were also obtained, and the antitumor mechanism of action was also investigated.

Fig. 3.

Design for the 6-acrylic phenethyl ester-2-pyranone derivatives

Results and discussion

Chemistry

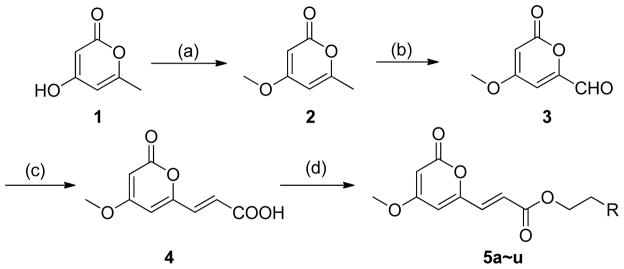

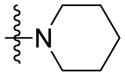

The series-5 target compounds were synthesized according to the approaches illustrated in Scheme 1. Compounds 2 and 3 were synthesized according to literature methods.23 Initially, compound 2 was obtained by methylation of commercially obtained 4-hydroxy-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (1). Then, the methyl group at C-6 of 2 was oxidized with selenium dioxide in 1, 4-dioxane in a sealed tube at 160 °C to yield 3. The intermediate (E)-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylic acid (4) was obtained in 47% yield through a Knoevenagel condensation reaction with the reaction temperature set at 110 °C. As we known, the general condition of Knoevenagel condensation reaction to afford cinnamic acid derivatives is with piperidine as the base, pyridine as the solvent, and the reaction temperature is at room temperature. Since the lactone ring in the target compound was not stable in strong basic solution, we had explored several bases, such as K2CO3, Et3N, EtONa, and piperidine. As a result, piperidine was the best. To discover the best solvent, we had explored methanol, ethanol, and pyridine. Pyridine was the commonly used solvent for Knoevenagel condensation, and we found it was also the best solvent to afford our desired compound 4. The reaction temperature was also optimized. Room temperature, 60 °C, and reflux temperature were investigated, and we found reflux reaction temperature was the best. So we chose piperidine as the base, pyridine as the solvent, and the reaction temperature was at reflux. Finally, our desired series-5 compounds were prepared from 4 through an esterification reaction using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC·HCl) as a condensing reagent. The obtained yields were varied from 49% to 71%.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 5a~u. Reagents and conditions: (a) Me2SO4, K2CO3, acetone, r.t., 16 h, 84%; (b) SeO2, dioxane, 160 °C, 4 h, 91%; (c) CH2(COOH)2, pyridine, piperidine, reflux,3 h, 47%; (d) phenethyl alcohols or heterocyclic EtOHs, EDC·HCl, DMAP, CH2Cl2, r.t., overnight, 49% – 71%.

Antitumor activity against five human cancer cell lines

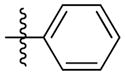

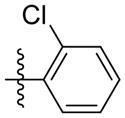

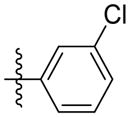

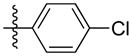

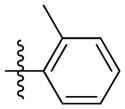

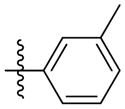

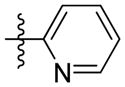

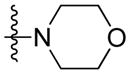

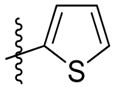

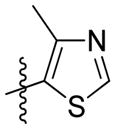

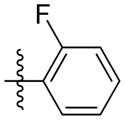

To evaluate the effects of 5-derivativeson the growth of human cancer cells, the growth inhibitory potential was evaluated using a MTT assay in five human cancer cells. Initially, 12 compounds (5a–l) were screened at 20 μM. Only compounds 5b and 5e exhibited significant in vitro antitumor activity (greater than 50% growth inhibition) against the tested human cancer cell lines at this concentration. Table 1 lists the IC50 values for the active compounds. Interestingly, both 5b and 5e were substituted at C-2 of the benzene ring, while the inactive compounds (5a, 5c, 5e, 5f, and 5g) were substituted at the C-3 or C-4 position or contained a heterocyclic rather than benzene ring (5h–l). While substitution at C-2 sharply affected the antitumor activity, both chlorine and methyl groups had similar impacts (compare 5b vs 5e). Moreover, both new lactone-containing CAPE-derivatives were more active than CAPE, especially against MCF-7, HSC-2, and HeLa cancer cell lines.

Table 1.

In vitro cytotoxicity data for 5a–l against five human tumor cell lines

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | C6 | HSC-2 | HeLa | A549 | ||

| CAPE | CAPE | NAb | NAb | NAb | NAb | NAb |

| 5a |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5b |

|

6.56 | NAb | 1.24 | 1.14 | NAb |

| 5c |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5d |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5e |

|

3.13 | 6.77 | 0.92 | 2.31 | 10.3 |

| 5f |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5g |

|

NAb | –a | –a | 8.27 | –a |

| 5h |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5i |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5j |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5k |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5l |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

growth inhibition did not reach 50% at 20 μM

NA = IC50> 10 μM

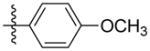

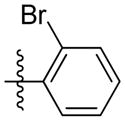

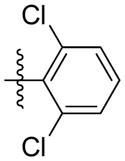

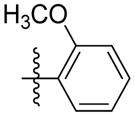

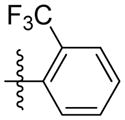

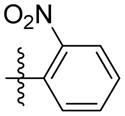

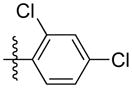

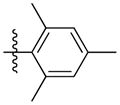

On the basis of the preliminary results, nine additional 5-derivatives were synthesized to more fully evaluate the effects of substituents at C-2 on the cytotoxicity. Compounds 5m–u contained-F, -Br, -OCH3, -CF3, and -NO2 substituents, as well as multiply substituted phenyl rings or a naphthyl ring. The assay results are shown in Table 2. Compounds with a 2-F or 2-NO2 group (5m and 5r, respectively) were inactive against all cancer cell lines, whereas the derivative with a 2-Br group (5n) was active against four cell lines. These results demonstrated that stronger electron-withdrawing inductive effects decreased the antitumor activity. Compounds with a 2-methoxy (5p) or 2-trifluoromethyl (5q) group were active only against the HeLa cell lines, which appeared to have the greatest sensitivity to this compound class. Among the compounds with multiple substituents on the phenyl ring, the 2,4,6-trimethylated compound (5t) showed significant activity against the MCF-7, HSC-2, and HeLa cell lines. Comparison of 5o, 5b, and 5s indicated that the former compound with a 2,6-disubstituted benzene ring displayed better activity against all five tested cell lines than the latter compounds with 2- or 2,4-substitution. Finally, when the benzene ring was changed to a naphthalene ring (5u), no cytotoxicity was observed. This finding indicated that greater steric bulk could lead to decreased antitumor activity.

Table 2.

In vitro cytotoxicity data for 5m–u against five human tumor cell lines

| Compound | Structure | IC 50(μM)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | C6 | HSC-2 | HeLa | A549 | ||

| 5m |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5n |

|

5.01 | NAb | 2.62 | 1.47 | 7.03 |

| 5o |

|

2.61 | 3.45 | 1.19 | 0.50 | 1.15 |

| 5p |

|

NAb | NAb | NAb | 5.63 | NAb |

| 5q |

|

NAb | –a | –a | 9.13 | –a |

| 5r |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

| 5s |

|

NAb | NAb | 9.45 | 6.26 | NAb |

| 5t |

|

7.99 | NAb | 3.52 | 1.49 | NAb |

| 5u |

|

–a | –a | –a | –a | –a |

growth inhibition did not reach 50% at 20 μM

NA = IC50> 10 μM

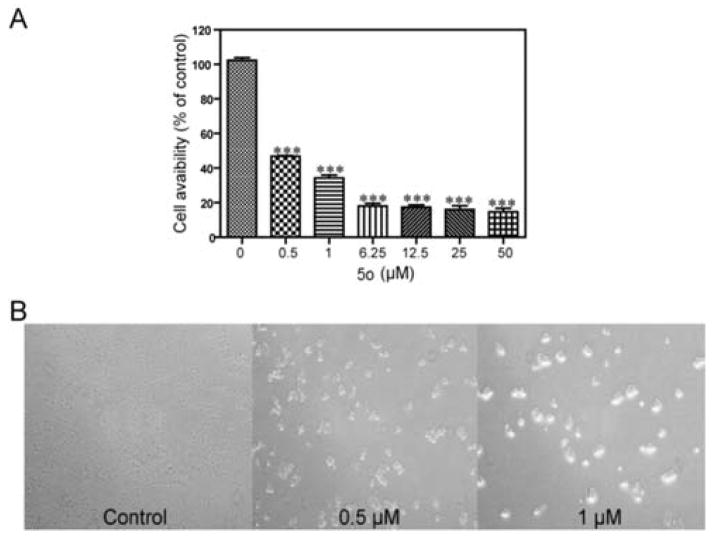

Among all 21 compounds, 5o showed most potent activity against the five tested human tumor cell lines (IC50: 2.61, 3.45, 1.19, 0.50, and 1.15 μM). Moreover, the lowest IC50 value for 5o (0.50 μM) was obtained in HeLa cells compared with the other cell lines. The effect of 5o on cell proliferation in HeLa cell lines was also assayed as shown in Fig. 3. Cells treated with 5o (0.5 and 1 μM) displayed morphological changes and showed distinctly rounded shapes compared with the control cells (Fig. 3B). This result prompted us to study the mechanism of action of 5o in HeLa cell lines.

Fig. 3.

The inhibitory effects of 5o on HeLa cell growth. (A) Cells were treated or untreated with increasing concentrations (0.5–50 μM) of 5o for 48 h. (B) Effects on cell morphology after treatment with 5o (0.5, 1 μM) under phase contrast microscope at 100× magnification. ***Significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.001).

Cell cycle effects of 5o

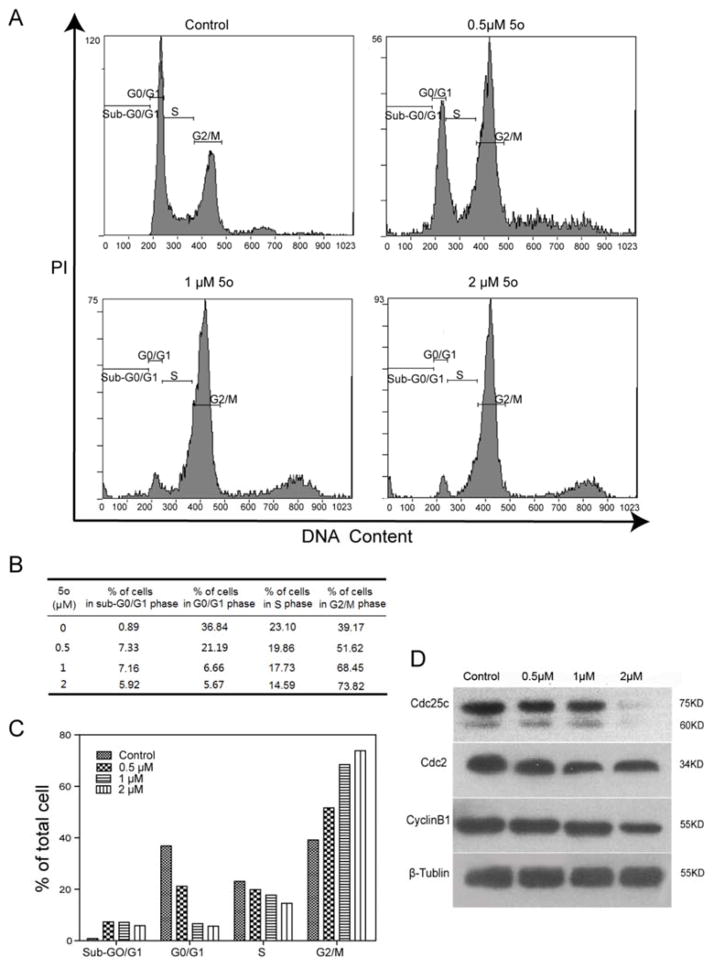

Based on previous investigation, cell proliferation is associated with regulation of three phases (G0/G1, S, and G2/M) of the cell cycle. To investigate if growth inhibition induced by 5o was associated with regulation of the cell cycle, cycle distribution of HeLa cells with or without 5o treatment was analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4B, the untreated group of HeLa cells had a low proportion of cells in G2/M (39.17%), while the experimental groups treated with 5o (0.5, 1, and 2 μM) for 24 h showed increased proportions of G2/M phase cells (51.62%, 68.45%, and 73.82%, respectively). These results suggested that 5o inhibited cell growth by arresting the cell-cycle at the G2/M phase in a concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, sub-G0/G1 phase cells were observed after 5o exposure (Fig. 4A), which indicated 5o induced apoptosis of HeLa cells.

Fig. 4.

5o induced G2/M arrest by modulating the expression of cell cycle-related proteins in G2/M phase. (A) Cells were treated with 5o (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM) for 24 h, and stained with PI and RNase A, then analyzed by flow cytometry to determine sub-G1 and cell-cycle phases. (B) Distribution of cells (%) treated with 5o in cell-cycle phases (Sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M). (C) The histogram analysis of Fig.4B. (D) After 5o (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM) treatment for 48 h, G2/M phase related protein (cyclin B1, Cdc 2, and Cdc25C) levels were detected by Western blot.

Cell cycle progression is driven by cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks).24 Generally, Cdc25c, Cdc2 kinases and CyclinB1 are primarily activated at the G2/M phase.25 The cell cycle transition from G2 phase to M phase is controlled by Cdc2/CyclinB1 kinase complex activity, which is activated by Cdc25C. Cdc25C activity is a rate-limiting process for G2/M phase transition.24b Subsequent experiments were performed to analyze changes in the expression of key G2/M checkpoint regulatory proteins using Western blot. As shown in Fig. 4D, cells treated with 5o for 48 h had decreased levels of CyclinB1, mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc2, and mitotic Cdc25C in a dose-dependent manner. These results are consistent with G2/M arrest and demonstrated that 5o inhibited proliferation HeLa cells by G2/M-phase arrest.

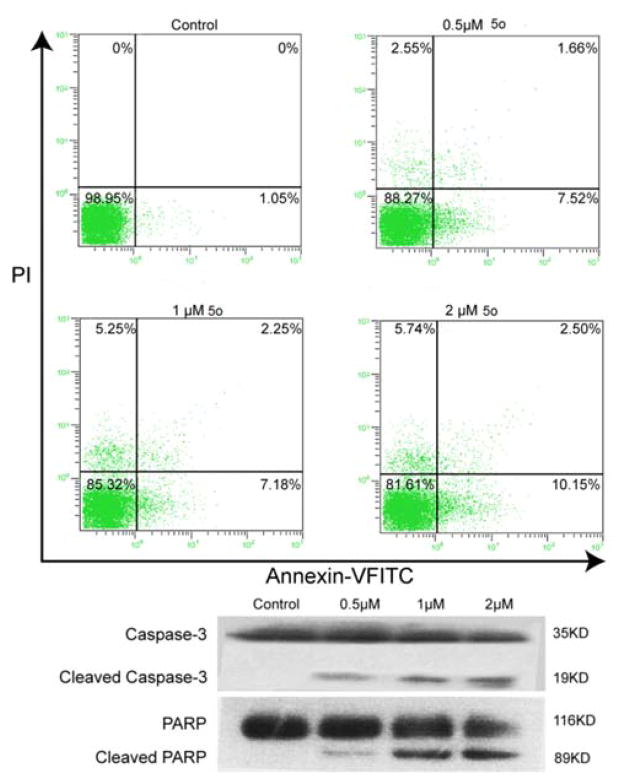

Induction of apoptosis by 5o in HeLa cell lines

As a natural process of programmed cell death (PCD), apoptosis plays an important role in cell clearance. Based on current studies, extensive apoptosis is observed in regressing tumor cells and also in those cells treated with chemotherapeutic agents.26 Various evidence has shown that apoptosis is the most crucial and renowned mechanism for clearance of tumor cells.27 Apoptosis tolerance may result in treatment resistance.28 In the previous analysis of 5o’s effect on the cell cycle, a sub-G0/G1 peak was observed (Fig. 4A). In order to confirm that the sub-G0/G1 peak was caused by apoptosis rather than by cell debris, quantitative apoptotic analysis was performed by using an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Becton Dickinson, USA). As shown in Fig. 5A, in HeLa cells treated with 5o at indicated concentrations for 24 h, the percentages of early/late apoptotic cells were 7.52%/1.66%, 7.18%/2.25%, and 10.2%/2.50% compared to control (1.05%/0%). These results indicated that 5o induced HeLa cell apoptosis, especially early apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

5o induces apoptosis via a caspase-dependent pathway. (A) HeLa cell lines were treated with 5o (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM) for 24 h, and stained with Annexin-V FITC/PI, then analyzed by flow cytometry to evaluate apoptosis. (B) Western blot analysis of apoptosis-related proteins (caspase-3 and PARP) level in HeLa cell lines exposed to 5o (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM) for 48 h.

To further confirm that 5o induced apoptosis, the expressions of key apoptosis-related proteins, such as caspase-3 and PARP, were detected by Western blot assay. Caspase proteins play a central role in the execution-phase of cell apoptosis. Among caspase proteins, caspase-3 is a critical executioner of apoptosis. Caspase-3 can be activated both by extrinsic (death ligand) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathways.29 Caspase-3 activation is dominant and reflected in the cleavage of PARP, which is a substrate of caspase-3.30 Cleavage of PARP results in DNA repair inhibition and DNA degradation. As shown in Fig. 5B, treatment with 5o for 48 h significantly increased the level of cleaved caspase-3 (active form of caspase-3) in a dose-dependent manner compared with control group. At the same time, total full-length PARP (116 kDa) was cleaved to large fragment (89 kDa), and cleaved PARP also increased remarkably in a dose-dependent manner. These findings corresponded with the activation of caspase-3 and the data demonstrated that 5o induced HeLa cell apoptosis through activation of the caspase-mediated pathway.

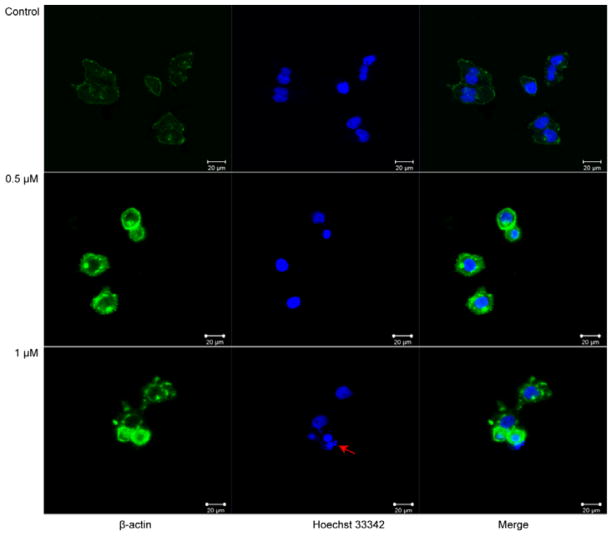

5o induced morphological changes by actin cytoskeleton disruption

As shown in Fig. 3B, significant changes in cell morphology were observed. HeLa cells treated with 5o (0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h exhibited distinctly round shape and detachment compared to the untreated cells. Cell morphology and adhesion are usually associated with the actin cytoskeleton.31 Therefore, immunofluorescence microscopy was used to explore the effect of 5o on actin cytoskeleton. In the control group, actin was diffusely distributed, whereas in the 5o-treated group (0.5 μM), actin was locally clustered. When HeLa cells were treated with 1 μM of 5o, actin aggregation was enhanced and actin disruption was also generated (Fig. 6). Additionally, apoptotic bodies (denoted by red mark), which are consistent with apoptosis-induced conclusion, were observed in HeLa cells treated with 1 μM of 5o. These results suggested that 5o induced actin aggregation and further disrupted the actin cytoskeleton. Because a disequilibrium of the actin dynamics between G-actin and F-actin can result in actin aggregation and influence cell shape and cell adhesion,32 we speculated that 5o induced actin aggregation and actin cytoskeleton disruption through disturbing the actin dynamic equilibrium. Actin dynamics is essential to cell division. G2/M-phase blockage of 5o may also contribute to the abnormal actin dynamics, but the detailed mechanism should be further confirmed.

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of actin cytoskeleton in HeLa cell lines with 5o treatment. Cells were either untreated or treated with 5o (0.5, 1 μM) for 24 h, and then immunofluorescence was observed as described in the Materials and Methods. The β-actin (green) was revealed by single-immunofluorescent staining. Nuclei (blue) were stained by Hoechst33342. Scale bar, 20 μM.

Inhibition of cell migration and invasion

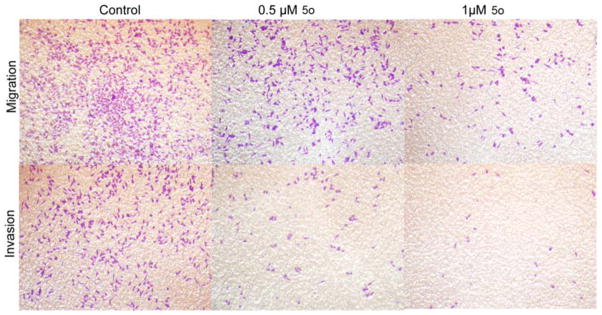

Malignant tumor invasion and metastasis have been hot and difficult research topics in oncology. Tumor cells use their intrinsic migratory ability to invade adjacent tissues and the vasculature and, ultimately, to metastasize.33 Migration and invasion of cancer cells is dependent on the actin cytoskeleton,34 which is driven by the polymerization of actin within two distinct structures, lamellipodia and filopodia, and attachment to the extracellular matrix through actin-rich adhesive structures.35 In previous confocal assays, we observed that the 5o disturbed the actin dynamics and disrupted the actin cytoskeleton. Subsequently, we conducted invasion and migration assays to explore whether 5o influenced the migration and invasion abilities of HeLa cells. In Fig. 7, HeLa cells with or without treatment of different doses of 5o were stained by crystal violet. As shown in Fig. 7, in matrigel-coated (for migration ability) or -noncoated (for invasion ability) transwell assay, the numbers of HeLa cells passing through the filter were significantly decreased in response to increasing concentration of 5o. These results demonstrated that 5o could markedly inhibit both migration and invasion ability of HeLa cells.

Fig. 7.

Compound 5o inhibited HeLa cell lines migration and invasion in transwell assay. Invasion potential of HeLa cells passing through matrigel-coated transwell after treatment with indicated concentration of 5o for 24 h. Migration potential is without matrigel. These images show the number of HeLa cells passing through the filter with/without matrigel. As the 5odose increased, the number of cells on the undersurface of the filter decreased.

Preliminary ADMET Study

To investigate the drug-like profiles of the synthesized compounds, we submitted several 5-series compound for preliminary ADMET prediction (Table 3). Improved blood brain barrier penetration (BBB) and decreased liver toxicity were calculated for 5o in comparison with CAPE. In addition, calculations indicated that 5o had good absorption and solubility and could easily be bound to carrier proteins in the blood, while showing no inhibition of CYP2D6. However, 5o should still be evaluated experimentally and further optimized regarding its pharmacokinetics properties.

Table 3.

The parameters of ADMET descriptors of 5 series.

| Compound | BBBa | Absorptionb | Solubilityc | Hepatotoxicityd | CYP2D6e | PPBf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5b | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5e | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 5g | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 5n | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 5o | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5p | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 5q | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5s | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 5t | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CAPE | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

BBB is blood brain barrier penetration and predicts blood-brain penetration after oral administration. 1 (High), 2 (Medium);

Absorption predicts human intestinal absorption (HIA) after oral administration. 0 (Good);

Solubility predicts the solubility of each compound in water at 25 °C. 2 (low), and 3 (good);

Hepatotoxicity predicts potential liver toxicity of compounds. 0 (Nontoxic), 1 (Toxic);

CYP2D6 predicts CYP2D6 enzyme inhibition using 2D chemical structure. 0 (Non-inhibitor);

PPB predicts whether a compound is likely to be highly bound to carrier proteins in the blood. 1 (binding ability > 90%), 2 (binding ability > 95%).

Conclusion

In summary, the acrylic phenethyl ester portion of CAPE was combined with the 4-methoxy-2H-pyran-2-one of styryl-2-pyrone, and a series of 6-acrylic phenethyl ester-2-pyranone derivatives were designed and synthesized. Among the new compounds, 5o exhibited significantly more anti-proliferation activity than CAPE against five human cancer cell lines. Particular efficacy was observed against the HeLa cell lines (IC50 = 0.50 μM). Flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle demonstrated an increased percentage of G2/M phase cells in 5o-treated cells. More importantly, 5o induced HeLa cells apoptosis via a caspase-3-dependent manner. Moreover, further study indicated that 5o influenced invasion and migration in HeLa cells by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton. In addition, based on in silico ADMET predictions, compound 5o is likely to demonstrate good ADMET properties with low hepatotoxicity. These findings suggest that 5o is a promising compound for further study to generate a clinical trial candidate for the treatment of cancer.

Experimental

Synthesis

Materials and equipment

Reagents were used without further purification unless otherwise specified. Solvents were dried and redistilled prior to use with usual methods. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using TMS as the internal standard on a BrukerBioSpin GmbH spectrometer (AvanceIII, Switzerland) at 400 MHz and 100 MHz. Coupling constants are given in Hz. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained using a Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF mass spectrometer. Flash column chromatography was performed using silica gel (200-300 mesh) purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co. Ltd or alumina from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. All reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography using silica gel.

Synthesis of 4-methoxy-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (2)23

To a suspension of K2CO3 (62.4 g, 452.4 mmol) in anhydrous acetone (200 mL) under nitrogen was added Me2SO4 (9.8 mL, 103.2 mmol). Then, the substrate 4-hydroxy-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (1) (10.0 g, 79.36 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. Then, the system was filtered, the obtained solid was washed with acetone, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. After purification by flash chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1/4) and recrystallization EtOAc/petroleum ether, the methylated product 4-methoxy-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (9.3 g, 84 %) was obtained as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH 5.74 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.37 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 3.75 (3H, s), 2.17 (3H, s).

Synthesis of 4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-carbaldehyde (3)23

Under nitrogen, 4-methoxy-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (2) (5.6 g, 40 mmol) and SeO2 (22 g, 200.0 mmol) were dissolved in dry dioxane (150 mL), inside a sealed tube. The mixture was heated to 160 °C for 4 h. Then, the reaction was cooled to room temperature and filtered, and the filter cake was washed with EtOAc (30 mL). The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1/1) to afford the aldehyde (3) (5.6 g, 91 %) as a yellowish solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH 9.51 (1H, s), 6.67 (1H, s), 5.74 (1H, s), 3.86 (3H, s).

Synthesis of (E)-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylic acid (4)36

A solution of aldehyde (3) (3.08 g, 20.0 mmol), malonic acid (2.08 g, 20.0 mmol) in pyridine (10 ml, 120 mmol) and piperidine (0.1 ml) was heated to reflux for 3 h. The resulting solution was poured into 2 M HCl aq. and cooled to room temperature. The solid was filtered and washed with water. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (MeOH/dichloromethane = 3/50) to afford the acrylic acid (4) (1.84 g, 47 %) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δH 7.23 (1H, dd, J = 15.7, 2.6 Hz), 6.71 (1H, s), 6.41 (1H, dd, J = 15.7, 2.8 Hz), 5.79 (1H, s), 3.84 (3H, s); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δC169.9, 166.3, 162.0, 155.3, 133.9, 124.1, 106.3, 91.2, 56.6; MS (ESI): m/z 195.0 [M-H]−; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C9H8O5 [M-H]−, 195.0299; Found, 195.0293.

General procedure for the preparation of (E)-phenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H- pyran-6-yl) acrylate and its derivatives (5a~u)37

To a stirred solution of acrylic acid (4) (0.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) were added EDC·HCl (1.2 eq.), DMAP (0.1 eq.), and the corresponding phenethyl alcohol (1.2 eq.), and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1/3) to give the corresponding ester (5a~u).

Synthesis of (E)-phenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5a)

Following the general procedure, 5a was obtained as a white solid (54.1 mg, 60 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH7.22-7.33 (5H, m), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.41 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 2.99 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.8, 155.6, 137.6, 133.8, 128.9, 128.5, 126.6, 124.5, 106.1, 91.3, 65.6, 56.2, 35.0; MS (ESI): m/z 301.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H16O5Na [M+Na]+, 323.0890; Found, 323.0921.

Synthesis of (E)-2-chlorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5b)

Following the general procedure, 5b was obtained as a white solid (68.1 mg, 68 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.37 (1H, dd, J = 7.2, 1.9 Hz), 7.28-7.18 (3H, m), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.44 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.14 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.8, 155.6, 135.3, 134.2, 133.9, 131.2, 129.6, 128.2, 126.9, 124.4, 106.2, 91.4, 63.9, 56.2, 32.8; MS (ESI): m/z 335.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15ClO5Na [M+Na]+, 357.0500; Found, 357.0522.

Synthesis of (E)-3-chlorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5c)

Following the general procedure, 5c was obtained as a white solid (52.1 mg, 52 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.28-7.20 (3H, m), 7.12 (1H, dt, J = 6.7, 1.7 Hz), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.12 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.40 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 2.97 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8, 155.6, 139.7, 134.0, 134.0, 129.8, 129.0, 127.1, 126.9, 124.3, 106.3, 91.4, 65.1, 56.2, 34.7; MS (ESI): m/z 335.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15ClO5Na [M+Na]+, 357.0500; Found, 357.0529.

Synthesis of (E)-4-chlorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5d)

Following the general procedure, 5d was obtained as a white solid (65.1 mg, 65 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.28 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.17 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.38 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz),3.84 (3H, s), 2.96 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8, 155.6, 136.1, 134.0, 132.5, 130.2, 128.7, 124.3, 106.2, 91.4, 65.2, 56.2, 34.4; MS (ESI): m/z 335.0 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15ClO5Na [M+Na]+, 357.0500; Found, 357.0519.

Synthesis of (E)-2-methylphenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5e)

Following the general procedure, 5e was obtained as a white solid (51.8 mg, 55 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.20 - 7.12 (4H, m), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.38 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 3.00 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.36 (3H, s); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.8, 155.7, 136.4, 135.6, 133.8, 130.4, 129.6, 126.8, 126.1, 124.5, 106.1, 91.4, 64.7, 56.1, 32.3, 19.3; MS (ESI): m/z 315.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C18H18O5Na [M+Na]+, 337.1046; Found, 337.1062.

Synthesis of (E)-3-methylphenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5f)

Following the general procedure, 5f was obtained as a white solid (52.8 mg, 56 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.20 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.02-7.08 (4H, m), 6.71 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.40 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 2.95 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 2.34 (3H, s); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.8, 155.7, 138.1, 137.5, 133.8, 129.7, 128.4, 127.4, 125.9, 124.6, 106.1, 91.3, 65.7, 56.1, 35.0, 21.3; MS (ESI): m/z 315.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C18H18O5Na [M+Na]+, 337.1046; Found, 337.1069.

Synthesis of (E)-4-methoxyphenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5g)

Following the general procedure, 5g was obtained as a white solid (63.9 mg, 71 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.15 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.86 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.71 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.37 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.80 (3H, s), 2.93 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.0, 165.6, 162.8, 158.4, 155.7, 133.8, 129.9, 129.6, 124.6, 114.0, 106.1, 91.3, 65.8, 56.2, 55.2, 34.2; MS (ESI): m/z 353.2 [M+Na]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C18H18O6Na [M+Na]+, 353.0996; Found, 353.1026.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(piperidin-1-yl)ethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5h)

Following the general procedure, 5h was obtained as a white solid (50.0 mg, 51 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.10 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.12 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.33 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 2.67 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz), 2.47(4H, t, J = 4.9 Hz), 1.59 (4H, dt, J = 11.1, 5.6 Hz), 1.44 (2H, dt, J = 10.3, 4.7 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.8, 155.7, 133.8, 124.6, 106.1, 91.3, 62.9, 57.2, 56.1, 54.8, 25.9, 24.1; MS (ESI): m/z 308.1 [M+H]+.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(pyridin-2-yl)ethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5i)

Following the general procedure, 5i was obtained as a white solid (45.0 mg, 50 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.56 (1H, d, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.64 (1H, td, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz), 7.24 – 7.12 (2H, m), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.10 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.60 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 3.17 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.0, 165.6, 162.8, 157.8, 155.6, 149.5, 136.5, 133.8, 124.4, 123.5, 121.7, 106.1, 91.3, 64.2, 56.2, 37.3. MS (ESI): m/z302.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C16H21NO5Na [M+Na]+, 324.0842; Found, 324.0860.

Synthesis of (E)-2-morpholinoethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5j)

Following the general procedure, 5j was obtained as a white solid (52.9 mg, 57 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.10 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.13 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.34 (2H, t, J = 5.7 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.72 (4H, t, J = 4.6 Hz), 2.70 (2H, t, J = 5.7 Hz), 2.54 (4H, t, J = 4.6 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.7, 155.6, 134.0, 124.4, 106.2, 91.4, 66.8, 62.3, 57.0, 56.2, 53.8; MS (ESI): m/z 310.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C15H19NO6 [M+H]+, 310.1285; Found, 310.1281.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(thiophen-2-yl)ethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5k)

Following the general procedure, 5k was obtained as a white solid (63.4 mg, 69 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.17 (1H, dd, J = 5.1, 1.1 Hz), 7.10 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.95 (1H, dd, J = 5.1, 3.5 Hz), 6.88 (1H, dd, J = 3.4, 0.9 Hz), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.12 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.42 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.21 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.7, 155.6, 139.6, 134.0, 126.9, 125.6, 124.4, 124.1, 106.2, 91.4, 65.2, 56.1, 29.2; MS (ESI): m/z 307.0 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C15H14O5SNa [M+Na]+, 329.0454; Found, 329.0465.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)ethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5l)

Following the general procedure, 5l was obtained as a white solid (60.7 mg, 63 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.60 (1H, s), 7.10 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.71 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.13 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.60 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.37 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.16 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 2.43 (3H, s); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.4, 162.7, 155.5, 150.0, 149.9, 134.3, 126.4, 124.0, 106.4, 91.5, 64.6, 56.2, 25.8, 14.9; MS (ESI): m/z 344.1 [M+Na]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C15H15NO5SNa [M+Na]+, 344.0563; Found, 344.0581.

Synthesis of (E)-2-fluorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5m)

Following the general procedure, 5m was obtained as a white solid (60.1 mg, 63 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.26 -7.18 (2H, m), 7.12 - 6.99 (3H, m), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.41 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 3.04 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.7 (d, J = 33.6 Hz), 160.0, 155.6, 133.9, 131.2 (d, J = 4.5 Hz), 128.5 (d, J = 8.2 Hz), 124.5 (d, J = 15.8 Hz), 124.4, 124.1 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 115.3 (d, J = 21.8 Hz), 106.2, 91.3, 64.3, 56.2, 28.5; MS (ESI): m/z 319.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15FO5Na [M+Na]+, 341.0796; Found, 341.0825.

Synthesis of (E)-2-bromophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5n)

Following the general procedure, 5n was obtained as a white solid (77.1 mg, 68 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.55 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.27 (2H, d, J = 4.3 Hz), 7.14 - 7.05 (2H, m), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.44 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.83 (3H, s), 3.15 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8, 155.6, 137.0, 133.9, 132.9, 131.2, 128.5, 127.6, 124.6, 124.3, 106.2, 91.4, 64.0, 56.2, 35.2; MS (ESI): m/z 379.1 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15BrO5Na [M+Na]+, 400.9995; Found, 401.0025.

Synthesis of (E)-2, 6-dichlorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5o)

Following the general procedure, 5o was obtained as a white solid (69.6 mg, 63 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.31 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.09 (1H, d, J = 15.7 Hz), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.45 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.37 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8, 155.7, 135.9, 133.9, 133.6, 128.5, 128.3, 124.4, 106.2, 91.3, 62.6, 56.2, 30.4; MS (ESI): m/z 391.0 [M+Na]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H14Cl2O5Na [M+Na]+, 391.0111; Found, 391.0131.

Synthesis of (E)-2-methoxyphenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5p)

Following the general procedure, 5p was obtained as a white solid (68.3 mg, 69 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.25 – 7.14 (2H, m), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.92 – 6.83 (2H, m), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.09 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.39 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.82 (6H, s), 3.01 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.0, 165.7, 162.9, 157.6, 155.7, 133.6, 130.8, 128.0, 125.8, 124.7, 120.4, 110.3, 106.0, 91.3, 64.5, 56.1, 55.2, 29.9; MS (ESI): m/z 331.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C18H18O6Na [M+Na]+, 353.0996; Found, 353.1017.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5q)

Following the general procedure, 5q was obtained as a white solid (56.3 mg, 51 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.66 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.43 – 7.32 (2H, m), 7.08 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.12 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.43 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.19 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8 155.6, 136.1, 134.0, 131.8, 131.8, 128.8, 126.9, 126.2 (q, J = 5.6 Hz, 11.1 Hz), 124.3, 106.2, 91.4, 64.9, 56.2, 31.8; MS (ESI): m/z 369.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C18H15F3O5Na [M+Na]+, 391.0764; Found, 391.0798.

Synthesis of (E)-2-nitrophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5r)

Following the general procedure, 5r was obtained as a white solid (72.5 mg, 70 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.97 (1H, d, J = 8.16 Hz), 7.58 (1H, td, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz), 7.46 – 7.39 (2H, m), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.66 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.14 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.51 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.32 (2H, t, J = 6.3 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.0, 165.4, 162.8, 155.5, 149.6, 134.1, 133.1, 132.8, 132.8, 128.0, 125.0, 124.0, 106.3, 91.4, 64.5, 56.2, 32.3; MS (ESI): m/z 346.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H15NO7Na [M+Na]+, 368.0741; Found, 368.0772.

Synthesis of (E)-2, 4-dichlorophenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5s)

Following the general procedure, 5s was obtained as a white solid (71.8 mg, 65 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.39 (1H, s), 7.20 (2H, d, J = 1.4 Hz), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.12 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.41 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.10 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.5, 162.8, 155.5, 134.8, 134.0, 133.9, 133.3, 131.9, 129.4, 127.2, 124.1, 106.3, 91.4, 63.6, 56.2, 32.2; MS (ESI): m/z 369.0 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C17H14Cl2O5Na [M+Na]+, 391.0111; Found, 391.0143.

Synthesis of (E)-2,4,6-trimethylphenethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5t)

Following the general procedure, 5t was obtained as a white solid (50.3 mg, 49 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.09 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.85 (2H, s), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.59 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.27 (2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.02 (2H t, J = 7.7 Hz), 2.34 (6H, s), 2.25 (3H, s); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC169.9, 165.7, 162.8, 155.7, 136.8, 136.0, 133.9, 130.6, 129.1, 124.5, 106.2, 91.4, 63.8, 56.2, 28.5, 20.8, 19.9; MS (ESI): m/z 365.2 [M+Na]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C20H22O5Na [M+Na]+, 365.1359; Found, 365.1390.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl-3-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl) acrylate (5u)

Following the general procedure, 5u was obtained as a white solid (60.9 mg, 58 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.10 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.76 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.58 – 7.36 (4H, m), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.06 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 5.57 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.53 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.82 (3H, s), 3.46 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δC 169.9, 165.6, 162.6, 155.6, 133.9, 133.5, 132.0, 130.9, 128.9, 127.5, 127.1, 126.2, 125.7, 125.5, 124.4, 123.5, 106.2, 91.4, 65.1, 56.1, 32.1; MS (ESI): m/z 351.2 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd for C21H18NO5Na [M+Na]+, 373.1046; Found, 373.1072.

Cell culture

HeLa, HSC-2, and A549 cell lines were kindly provided by Professor Li Haiou (Japan). MCF-7 and C6 were purchased from Center of Experiment Animal of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Hyclone). These cells were grown in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C and subcultured every three days.

Antiproliferative Assays

These derivatives were evaluated for their antiproliferative activity in five different cancer cell lines with MTT assay. Cells in log-phase were plated into 96-well plates with a density of 3.5×104 cells/mL overnight at 37 °C. Cells were then treated with various concentrations of compounds and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 48 h. The antiproliferative activities of compounds were evaluated by MTT. In brief, 20 μL of MTT reagent was added to each well and the plates continued to incubate for another 4 h at 37 °C. Formazan crystals were dissolved in 120 μL of DMSO. The optical density was assayed at 490 nm with an automated micro-plate reader (Thermo, Multiskan Ascent, USA) and the 50% inhibition concentration was determined from a dose-response curve.

Cell cycle analysis

HeLa cells (2×105 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates for 24 h. Compound 5o was added into each well in various concentrations (0.5, 1, 2 μM). Cells were harvested with trypsin and fixed with ice-cold 70% EtOH at 4 °C overnight. EtOH was washed with ice-cold PBS buffer. Finally, samples were stained with Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis Kit (Beyotime, China) for 30 min at 37 °C. The DNA contents of 11000 events were measured by flow cytometry (Beckmen Coulter, EPICS XL, USA).

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis assay was assessed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assay kit (Becton Dickinson, USA). The cells were treated with 5o at concentrations of 0.5, 1 and 2 μM for 24 h. Both detached and attached cells were harvested with trypsin, washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then resuspended in 100 μL binding buffer. Five μL each of Annexin V-FITC solution and PI were added. The cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 h.

Immunofluorescence assay

HeLa cells (4×104 cells/well) were seeded on glass-bottom cell culture dishes for 24 h. After incubation in the presence or absence of 5o (0.5, 1 μM), cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5%Triton X-100 and 0.05% Tween-20, blocked for 1 h and immunostained with rabbit anti-β-actin (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the antibodies were removed and cells washed with PBS. The cells were incubated with CF488-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG (1:700), highly cross-absorbed (Biotium, USA). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (5mg/ml). Fluorescence images were captured under a Zeissfluorescent microscope (Zeiss, LSM710, Germany)

Migration and invasion assay

The vitro migration and invasion assays were carried out using 24-well plates with 8-μm pore size inserts (Transwell, Corning, USA). Only for the invasion assay, the upper chamber was coated with 100 μL diluted matrigel (0.5 mg/mL). Serum-free DMEM cells suspension (100 μL, 3 ×105 cells/mL) with/without 5o (0.5, 1 μM) was added in the upper chamber. Medium (600 μL) with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 36 h of incubation, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Then, cells on the upper membrane surface were removed with cotton swabs. Stained cells were photographed under a microscope.

Western blot assay

Treated cells were lysed with RIPA Lysis Buffer (P0013, Beyotime, China). The total protein quality was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce; Rockford IL, USA). The protein were denatured and separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE and then electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon PVDF, Millipore, Bedford). The membranes were washed with Tris-Buffered Saline and Tween 20 (PBST) and then blocked for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with special antibodies against β-tubulin, caspase3, PARP, CyclinB1, Cdc25c, Cdc2 (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) at 4 °C overnight and washed with TBST. Later, the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with TBST. Protein bands were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Westar Supernova, Cyanagen, Italy) and recorded on X-ray film (Fujifilm; Tokyo, Japan)

ADMET prediction

ADMET refers to absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of the drug in the body. We use ADMET descriptors module in Discovery studio (version 2.5, Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA.) to predict the ADMET properties according to molecular structure. The ADMET descriptors module estimates the aqueous solubility, blood brain barrier penetration (BBB), cytochrome P450 (CYP450) 2D6 inhibition, hepatotoxicity, human intestinal absorption (HIA) and plasma protein binding of a set of compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81173470, 81473138, 81172941), the National High-tech R&D Program of China (863 Program) (2012AA020307), and the introduction of innovative R&D team program of Guangdong Province (NO.2009010058). Partial support is also due to NIH grant CA177584 from the National Cancer Institute awarded to K.H. Lee.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zhou Z, Jemal A. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolba MF, Azab SS, Khalifa AE, Abdel-Rahman SZ, Abdel-Naim AB. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:699–709. doi: 10.1002/iub.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Ozturk G, Ginis Z, Akyol S, Erden G, Gurel A, Akyol O. Euro Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:2064–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Watabe M, Hishikawa K, Takayanagi A, Shimizu N. J Bio Chem. 2004;279:6017–6026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagaoka T, Banskota AH, Tezuka Y, Saiki I, Kadota S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:3351–3359. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin WL, Liang WH, Lee YJ, Chuang SK, Tseng TH. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;188:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Chen JH, Shao Y, Huang MT, Chin CK, Ho CT. Cancer Lett. 1996;108:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(96)04425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen YJ, Shiao MS, Hsu ML, Tsai TH, Wang SY. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5615–5619. doi: 10.1021/jf0107252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YJ, Liao PH, Chen WK, Yang CC. Cancer Lett. 2000;153:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Wu J, Omene C, Karkoszka J, Bosland M, Eckard J, Klein CB, Frenkel K. Cancer Lett. 2011;308:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Omene CO, Wu J, Frenkel K. Invest New Drug. 2012;30:1279–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel A, Ram VJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:7865–7913. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagen SE, Vara Prasad JVN, Boyer FE, Domagala JM, Ellsworth EL, Gjda C, Hamilton HW, Markkoski LJ, Steinbangh BA, Tait BD, Lunney EA, Tummino PJ, Ferguson D, Hupe D, Nouhan C, Gracheck SJ, Saunders JM, Roest SV. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3707–3711. doi: 10.1021/jm970522y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aytemir MD, Calis U, Ozalp M. Arch Pharm Med Chem. 2004;337:281–288. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200200754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairlamb IJS, Marrison LR, Dickinson JM, Lu FJ, Schmidt JP. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:4285–4299. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondoh M, Usui T, Kobayashi S, Tsuchiya K, Nishikawa K, Nishikiori T, Mayumi T, Osada H. Cancer Lett. 1998;126:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Shaw SJ, Menzella HG, Myles DC, Xian M, Smith AB., III Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:2753–2755. doi: 10.1039/b708884c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao H, Kusuma BR, Blagg BSJ. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:311–315. doi: 10.1021/ml100070r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Clark BR, Connor SO, Fox D, Leroy J, Murphy C. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:6306–6311. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05667k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao H, Donnelly AC, Kusuma BR, Brandt GEL, Brown D, Rajewski RA, Vielhauer G, Holzbeierlein J, Cohen MS, Blagg BJ. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3839–3853. doi: 10.1021/jm200148p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Touisni N, Maresca A, McDonald PC, Lou Y, Scozzafava A, Dedhar S, Winum JY, Supuran CT. J Med Chem. 2011;54:8271–8277. doi: 10.1021/jm200983e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yamamoto N, Renfrew AK, Kim BJ, Bryce NS, Hambley TW. J Med Chem. 2012;55:11013–11021. doi: 10.1021/jm3014713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhao H, Yan B, Peterson LB, Blagg BS. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:327–331. doi: 10.1021/ml300018e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kumar D, Mishra BA, Shekar KPC, Kumar A, Akamatsu K, Kurihara R, Ito T. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:6675–6679. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41224e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hyohdoh I, Furuichi N, Aoki T, Itezono Y, Shirai H, Ozawa S, Watanabe F, Matsushita M, Sakaitani M, Ho PS, Takanashi K, Harada N, Tomii Y, Yoshinari K, Ori K, Tabo M, Aoki Y, Shimma N, Iikura H. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:1059–1063. doi: 10.1021/ml4002419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Molzer C, Huber H, Steyrer A, Ziesel GV, Wallner M, Hong HT, Blanchfield JT, Bulmer AC, Wagner KH. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1958–1965. doi: 10.1021/np4005807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Yin Y, Wu X, Han HW, Sha S, Wang SF, Qiao F, Lu AM, Lv PC, Zhu HL. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:9157–9165. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01589d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Xiao J, Zhang Q, Gao YQ, Tang JJ, Zhang AL, Gao JM. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:3584–3590. doi: 10.1021/jf500054f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Sandhu S, Bansal Y, Silakari O, Bansal G. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:3806–3814. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Basanagouda M, Jambagi VB, Barigidad NN, Laxmeshwar SS, Devaru V, Narayanachar Euro J Med Chem. 2014;74:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Nasr T, Bondock S, Youns M. Euro J Med Chem. 2014;76:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Yadagiri B, Holagunda UD, Bantu R, Nagarapu L, Kumar CG, Pombala S, Sridhar B. Euro J Med Chem. 2014;79:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali MS, Tezuka Y, Awale S, Banskota AH, Kadota S. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:289–293. doi: 10.1021/np000496y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Z, Liao PC, Yang YL, Yang FL, Chen YL, Lam Y, Hua KF, Wu SH. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7967–7978. doi: 10.1021/jm100619x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Zhang D, Li Y, Chen W, Ruan Z, Deng L, Wang L, Tian H, Yiu A, Fan C, Luo H, Liu S, Wang Y, Xiao G, Chen L, Ye W. J Med Chem. 2013;56:5734–5743. doi: 10.1021/jm400881m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Bastow KF, Sun C-M, Lin YL, Yu HJ, Don MJ, Wu TS, Nakamura S, Lee KH. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5816–5819. doi: 10.1021/jm040112r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin RJ, Fontana G, Golding BT, Guiard S, Hardcastle IR, Leahy JJJ, Martin N, Richardson C, Rigoreau L, Stockley M, Smith GCM. J Med Chem. 2005;48:569–585. doi: 10.1021/jm049526a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Hsiang YH, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14873–4878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hsiang YH, Liu LF. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1722–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Staker BL, Hjerrild K, Feese MD, Behnke CA, Jr, Burgin AB, Stewart L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242259599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hsiang YH, Liu LF, Wall ME, Wani MC, Nicholas AW, Manikumar G, Kirschenbaum S, Silber R, Potmesil M. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4385–4389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Wang MJ, Liu YQ, Chang LC, Wang CY, Zhao YL, Zhao XB, Qian K, Nan X, Yang L, Yang XM, Hung HY, Yang JS, Kuo DH, Goto M, Morris-Natschke SL, Pan SL, Teng CM, Kuo SC, Wu TS, Wu YC, Lee KH. J Med Chem. 2014;57:6008–6018. doi: 10.1021/jm5003588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang P, Wang D, Su Y, Huang W, Zhou Y, Cui D, Zhu X, Yan D. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11748–11756. doi: 10.1021/ja505212y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang H, Xie H, Wu J, Wei X, Zhou L, Xu X, Zheng S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:11532–1537. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Duan J-X, Cai X, Meng F, Sun JD, Liu Q, Jung D, Jiao H, Matteucci J, Jung B, Bhupathi D, Ahluwalia D, Huang H, Hart CP, Matteucci M. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1715–1723. doi: 10.1021/jm101354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shen Y, Jin E, Zhang B, Murphy CJ, Sui M, Zhao J, Wang J, Tang J, Fan M, Kirk EV, Murdoch WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4259–4265. doi: 10.1021/ja909475m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Samori C, Guerrini A, Varchi G, Fontana G, Bombardelli E, Tinelli S, Beretta GL, Basili S, Moro S, Zunino F, Battaglia A. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1029–1039. doi: 10.1021/jm801153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Leu YL, Chen CS, Wu YJ, Chern JW. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1740–1746. doi: 10.1021/jm701151c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhang Z, Tanabe K, Hatta H, Nishimoto S. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:1905–1910. doi: 10.1039/b502813b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Wadkins RM, Bearss D, Manikumar G, Wani MC, Wall ME, Hoff DDV. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6679–6683. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Okuno S, Harada M, Yano T, Yano S, Kiuchi S, Tsuda N, Sakamura Y, Imai J, Kawaguchi T, Tsujihara K. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2988–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soldi C, Moro AV, Pizzolatti MG, Correia CRD. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:3607–3616. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Poli A, Mongiorgi S, Cocco L, Follo MY. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1471–1476. doi: 10.1042/BST20140128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lim S, Kaldis P. Development. 2013;140:3079–3093. doi: 10.1242/dev.091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang HL, Huang PJ, Chen SC, Cho HJ, Kumar KJ, Lu FJ, Chen CS, Chang CT, Hseu YC. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014 doi: 10.1002/em.21897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotter TG, Lennon SV, Glynn JG, Martin SJ. Anticancer Res. 1990;10:1153–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregory CD, Pound JD. J Pathol. 2011;223:178–195. doi: 10.1002/path.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Salvesen GS. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:3–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghavami S, Hashemi M, Ande SR, Yeganeh B, Xiao W, Eshraghi M, Bus CJ, Kadkhoda K, Wiechec E, Halayko AJ, Los M. J Med Genet. 2009;46:497–510. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Xu HL, Fu WW, Xin Y, Li MW, Wang SJ, Yu XF, Sui DY. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7919–792. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.18.7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Ann Rev Biophys. 2008;37:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dominguez R, Holmes KC. Ann Rev Biophys. 2011;40:169–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rafelski SM, Theriot JA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:209–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Adams CL, Nelson WJ, Smith SJ. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1899–1911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Zhang Y, Ouyang D, Xu L, Ji Y, Zha Q, Cai J, He X. Acta Bioch Bioph Sin. 2011;43:556–567. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Science. 2009;326:1208–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) van Zijl F, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Mutat Res. 2011;728:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamaguchi H, Condeelis J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Spano D, Heck C, De Antonellis P, Christofori G, Zollo M. Semin Cancer Bio. 2012;22:234–249. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krause M, Dent EW, Bear JE, Loureiro JJ, Gertler FB. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.050103.103356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vignjevic D, Montagnac G. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P, Hu HR, Huang ZH, Lei JY, Chu Y, Ye DY. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;22:7232–7236. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soda M, Hu D, Endo S, Takemura M, Li J, Wada R, Ifuku S, Zhao HT, El-Kabbani O, Ohta S, Yamamura K, Toyooka N, Hara A, Matsunaga T. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;48:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.