Abstract

Objective

To investigate patients’ preferences for outcomes associated with psychoactive medications.

Setting/design

Systematic review of stated preference studies. No settings restrictions were applied.

Participants/eligibility criteria

We included studies containing quantitative data regarding the relative value adults with mental disorders place on treatment outcomes. Studies with high risk of bias were excluded.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We restricted the scope of our review to preferences for outcomes, including the consequences from, attributes of, and health states associated with particular medications or medication classes, and process outcomes.

Results

After reviewing 11 215 citations, 16 studies were included in the systematic review. These studies reported the stated preferences from patients with schizophrenia (n=9), depression (n=4), bipolar disorder (n=2) and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (n=1). The median sample size was 81. Side effects and symptom outcomes outnumbered functioning and process outcomes. Severe disease and hospitalisation were reported to be least desirable. Patients with schizophrenia tended to value disease states as higher and side effects as lower, compared to other stakeholder groups. In depression, the ability to cope with activities was found to be more important than a depressed mood, per se. Patient preferences could not consistently be predicted from demographic or disease variables. Only a limited number of potentially important outcomes had been investigated. Benefits to patients were not part of the purpose in 9 of the 16 studies, and in 10 studies patients were not involved when the outcomes to present were selected.

Conclusions

Insufficient evidence exists on the relative value patients with mental disorders place on medication-associated outcomes. To increase patient-centredness in decisions involving psychoactive drugs, further research—with outcomes elicited from patients, and for a larger number of conditions—should be undertaken.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO CRD42013005685.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PSYCHIATRY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review on patients’ relative, stated preferences for outcomes of psychopharmacological treatments across methods and disorders.

We summarised patients’ preferences for hypothetical outcomes associated with medications and excluded preferences for specific medications or treatment domains, which are amenable to misconceptions. The treatments per se do not give value to the user; it is their outcomes that give value.

We tested and applied a broad, peer reviewed search strategy, but we might have overlooked or missed studies. Study quality was rigorously and comprehensively assessed.

Owing to the heterogeneity of methods and outcomes we could not perform quantitative summaries of the relative strengths of preferences.

Introduction

To respect and respond to patient preferences is a crucial aim in patient-centred healthcare1–3 and a persistent ideal in evidence-based medicine,4 clinical practice guidelines5 and shared decision-making.6 Integrating patient preferences is increasingly advocated in health technology assessments,7 drug development8 and market approval and reimbursement.9 Yet to allow patient preferences to guide healthcare decisions remains to become common practice.10

In the mental health field, healthcare decisions frequently involve medications: one in five Americans and one in eight western Europeans are prescribed psychotropic drugs.11 12 The psychopharmacological dilemmas faced by clinicians and patients are often preference-sensitive, and involve trade-offs of conflicting, multiple outcomes.13–15 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have summarised whether patients prefer pharmacological or psychological treatment,16 and the effect of matching the treatment to the patient's preferred option.17 18 However, in trade-off dilemmas, studies on patients’ preferred options might be less informative than studies on their preferences for the outcomes of the options. Knowledge about the relative strengths of preferences for treatment outcomes, representative for populations, can be gained with stated preference methods. A range of techniques is available.19–21 Systematic reviews of studies applying the techniques to elicit patient preferences for outcomes of psychotropic drugs are lacking. The current void of knowledge on the outcomes patients value the most and least, and what those outcomes should be,22 strikes the foundation of patient-centred care and suggests missed opportunities for more patient-centred decisions.

For these reasons we conducted a systematic review of studies on patients’ valuations of outcomes associated with psychoactive medications. The main goal was to summarise what is known on the relative strengths of preferences. We also reviewed:

Whether patient perspectives were part of the purpose and construction of outcomes

Which outcomes were addressed

The feasibility of stated preference methods for patients with mental disorders

Correlations between patient preferences and demographic or disease variables

Differences between patients’ preferences and those of other stakeholders

Methods

This study followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines (see online supplementary appendix 10): http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1000097

Eligibility criteria

Studies applying stated preference methods to elicit the relative values patients place on outcomes of psychopharmacological treatments, using quantitative methods, were eligible for inclusion. Studies that included rating scales only were excluded due to doubts about whether the techniques adequately measure strength of preference.19 No publication date, context or publication status restrictions were imposed.

We included studies on adult patients with direct experience of the mental disorder specified in the study, currently diagnosed with or at risk of recurrence of the disease. Trials addressing patients with substance-related and addictive disorders were excluded.

Patient preferences can be defined as “statements made by individuals regarding the relative desirability of a range of health experiences, treatment options, or health states”.23 We restricted the scope of our review to preferences for outcomes, including the consequences from, attributes of, and health states associated with particular medications or medication classes and process outcomes. Studies on patients’ preferences for specific medications, medication classes, or treatment domains, or for health states detached from a medication context, were not included. Studies measuring health-related quality of life were excluded unless they elicited patients’ relative valuations of outcomes.24 Studies calculating preferences by mapping life quality scales to utility scores were not included. Owing to the heterogeneity of the field, we did not specify the outcome measures in detail before the study.

Search strategy

We searched Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, SveMed+, The Health Technology Assessment Database, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database and grey literature databases from inception to September 2013. We piloted our strategies in a test search and modified the use of keywords and indexed terms. A PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) review was undertaken and the strategies revised. In the revised search, we used a combination of subject headings, subheadings and text words. The bibliographies of the included studies were hand searched for additional studies. Online supplementary appendix 1 details the search strategies.

Study selection

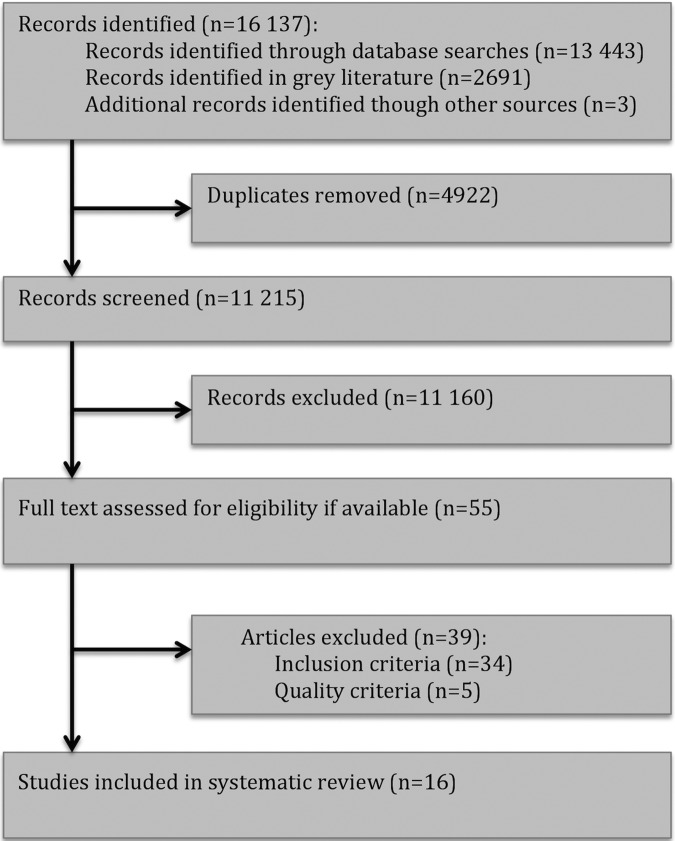

Two review authors (KN, BFL) independently reviewed all identified titles and abstracts (figure 1). Full text articles were obtained for potentially relevant trials and examined in detail by the same authors. Disagreements were discussed with the principal author (OE) and resolved by consensus.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Quality assessment

Standardised criteria for methodological quality and risk of bias in stated preference studies have not been established.25 26 To enable critical appraisal, we constructed a checklist based on criteria proposed for assessment of stated preference research in eight methodological reviews and evaluation tools.19 27–33 The resulting inventory consisted of 31 quality criteria within five domains: external validity, presentation of outcomes, minimisation of irrelevant variance, reporting and analysis, and other aspects (see online supplementary appendix 2). Two authors (KN, OE) independently assessed all studies considered for inclusion on the 31 items. Studies given an overall intermediate or high quality rating were included. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion.

Data collection

We developed, piloted and revised a data extraction form consistent with the goals of the review. Two reviewers (KN, OE) independently extracted data on the study, study population, preference elicitation aspects and preference results (see online supplementary appendix 3).

Results

Of 11 215 unique citations, 54 proceeded to full text review. We excluded 39 studies, the most frequent reason being lack of quantitative data on the relative strengths of the preferences (see online supplementary appendix 4). This left 16 studies for our systematic review. We present the results in descriptive and tabular form.

Study characteristics

Sixteen studies in 16 papers included 1785 patients with a median sample size of 81 (range 20–469). Nine studies had assigned patients with schizophrenic disorders, four had depressive disorders, two had bipolar disorders and one had ADHD (attention deficit hyperactive disorder). The range of reported mean ages was 39–46 and the median percentage of female participants 55. In the seven studies reporting ethnicity, the median percentage of Caucasians was 86. Ten studies included only outpatients, one inpatients and outpatients, and five did not report hospitalisation status. Twelve of the 16 studies were partly or fully conducted in the USA. Preference elicitation was the main or part of the main objective in 15 studies. Preferences were elicited from patients with the standard gamble (SG) method in six studies, conjoint analysis (CA) and pair-wise comparison (PC) in two studies each, discrete choice experiment (DCE) and willingness-to-pay (WTP) in two, and time trade-off (TTO) in one (table 1). Basic descriptions of the methods are provided in box 1.

Table 1.

Description of studies included in the systematic review

| Study | Condition | Country | Number* Included/Completed |

Number of women (%) | Mean age (years) | Caucasian (%) | Clinical setting | Method | Relevant medication | Funding from pharmaceutical company | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morss et al39 | Schizophrenia | USA | 33 | 2 (6) | 43 | 75 | Inpatient and outpatient | VAS, PC, SG | Antipsychotics | Yes | Side effects |

| Revicki et al48 | Schizophrenia | UK, USA | 49 | 12 (24.5) | 39 | 94 | Outpatient | Rating scale, PC | Psychopharmacological treatment | Yes | Symptoms, process related, functioning |

| Lenert et al46 | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder | USA | 22 | Not reported | 46 | Not reported | Outpatient | VAS, PC, SG | Antipsychotics | No | Side effects |

| Lee et al44 | Schizophrenia | USA | 20 | 12 (55) | Range: 18–60 | 40 | Mental health centre | VAS, SG | Antipsychotics | Yes | Symptoms, side effects |

| Lenert and Kaplan28 | Schizophrenia | USA | 148 | 49 (33) | 98%≤60 | Not reported† | Centres and practice organisations | VAS, SG | Antipsychotics | Yes | Symptoms, side effects |

| Shumway45 | Schizophrenia | USA | 50 | 17 (34.5) | 42 | 69 | Outpatient | Rating scales, CA | Antipsychotics | No | Symptoms, functioning, side effects, other |

| Briggs et al40 | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder | UK | 50/49 | 27 (55) | 44 | 94 | Outpatient | VAS, TTO | Antipsychotics | Yes | Symptoms, side effects, other |

| Bridges et al36 | Schizophrenia | USA, Germany | 105/97 | 50‡ | 44 | Not reported | Outpatient | Self-explicated method | Prescribed treatments | Yes | Symptoms, functioning, process related, other |

| Kinter et al42 | Schizophrenia | USA, Germany, New Zealand | 101/100 | 40 (40) | 43/42 | Not reported | Outpatient | CA | Antipsychotics | Yes | Symptoms, functioning, side effects, other |

| O'Brien et al38 | Mild or moderate depression | Canada | 95 | 69 (73) | 41 | Not reported | Outpatient | VAS, WTP | Antidepressants | Yes | Side effects, costs |

| Revicki and Wood47 | Major depressive disorder | USA, Canada | 70 | 54 (77) | 42 | Not reported | Outpatient | VAS§, SG | Antidepressants | Yes | Symptoms, side effects |

| Morey et al41 | Major depressive disorder | USA | 104 | 77 (74) | 40 | Not reported | Outpatient | WTP | Antidepressants | No | Side effects, costs, process related |

| Zimmer-mann et al35 | Depression | Germany | 255/227 | 140 (62) | Not reported¶ | Not reported | Outpatient | CA | Antidepressants | Yes | Symptoms, functioning, side effects, process related |

| Revicki et al43 | Bipolar disorder type I | USA | 96/92 | 51 (55.5) | 42 | 92 | Community hospital, research centre and health centre | VAS, SG | Mood stabilisers, antipsychotics | Yes | Symptoms, side effects, process related |

| Johnson et al34 | Bipolar disorder | USA | 469 | 295 (63) | 43 | 86 | Members of a web-based chronic illness panel | DCE** | Bipolar medications | Yes | Symptoms, side effects |

| Glenngård et al37 | ADHD | Sweden, Denmark, Norway | 116 | 66 (57) | Not reported | Not reported | Centres | DCE | Stimulants | Yes | Functioning, side effects, process related, costs |

*Patient participants only.

†31% African American or Hispanic.

‡Approximate percentage.

§VAS was used as a training exercise.

¶Largest age group 50–59 years.

**Choice-format trade-off questions.

CA, conjoint analysis; DCE, discrete choice experiment; PC, pairwise comparison; SG, standard gamble; TTO, time trade-off; VAS, visual analogue scale; WTP, willingness to pay.

Box 1. Stated preference methods in healthcare.

The standard gamble elicits the value of outcomes by asking patients to choose between a certain outcome and a gamble.

Willingness to pay is the maximum amount a patient is willing to offer to obtain good, or to avoid undesirable, outcomes.

In conjoint analysis, patients place weights on different features of a health option.

In pairwise comparison, patients compare health options in pairs to find which is preferred, or which has the largest amount of a measurable aspect.

In discrete choice experiments, patients state their preference over alternative scenarios, such as health states.

In time trade-off, patients are asked to choose between living in a suboptimal state for a certain period of time, versus living a healthier life for a shorter time.

Study quality

A frequently used quality criterion for stated preference studies is whether the outcomes are presented to the participants in adequate detail.28 The level of detail varied in the included studies, from short text descriptions to info-graphics and videos with actors enacting symptoms and side effects. All included studies minimised threats on validity from factors irrelevant to the represented outcomes using measures such as precomprehension or postcomprehension tests.

Non-random recruitment procedures limited the external validity in all studies. Four studies included less than 50 participants. In six studies, data were not reported for participants who did not complete the procedures. Authors generally provided incomplete information on study design, and five studies lacked measures of variance. The use of statistical techniques was deemed appropriate in all studies. Only two studies were given an overall ‘high quality’ rating (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Purposes

Seven studies related their results to potential benefits for individual patients, for instance to tailor adherence programmes,34 to be helpful in medical decision-making35 or to promote concordance between patients and psychiatrists.36 Although 13 of the studies received funding from a pharmaceutical company, only five studies suggested or performed economic analyses from an industry perspective.37–41 Eight studies discussed how their preference results could be used in public evaluation and prioritisation contexts (see online supplementary appendix 6).

Outcome sources

In 10 of the 16 studies, input from patients was not sought when outcomes were selected and constructed. The six studies that obtained patients’ perspectives used interviews,35 40 focus groups,36 42 piloting of the suggested outcomes39 43 or comments on patient websites.40 In comparison, six studies engaged clinicians and 13 studies reported using research or literature to identify the outcomes. Three used research or literature only38 44 45 (see online supplementary appendix 6).

Included outcomes

Side effects (n=14) and symptoms including relapse (n=11) were most frequently presented to participants. Six studies included process related outcomes, for instance, the treatment schedule, or number of visits to the hospital. Functioning featured in six studies and costs in three. While a large number of outcomes are potentially relevant,25 only a limited number was presented in the studies. For example, mortality or burden to relatives was not included in any study (see online supplementary appendix 6 and 9).

Feasibility and validity

The studies reported that patients were able to provide usable preference measures for the six methods applied, generally comprehended the tasks and gave sufficiently consistent answers. A total of 92–100% of the participants completed the procedures.

Three of the nine studies with patients with schizophrenia reported moderate or major problems. In the first, a small SG study, 30% of the patients did not understand the survey well and 56% had inconsistent rank ordering.46 In the second, also a SG study, patients made more logical errors than others and mostly, in contrast to other stakeholders, preferred not to correct their mistakes.28 In one of the two studies applying conjoint analysis, patients reported lower levels of understanding and more difficulty with the task compared to other participants.45 Minor or no problems were reported in the two schizophrenia studies applying TTO and self-explicated methods.

The studies including patients with depression, bipolar disorder and ADHD reported minor or no feasibility problems, but feasibility and validity were less focused on compared to the schizophrenia studies (see online supplementary appendix 7).

Correlations with patient characteristics

Eleven studies investigated whether patient preferences correlated with demographic or disease variables, with negative or conflicting findings.

Three studies found that preferences correlated with age,35 37 41 whereas five found no significant association.38 40 42 43 47 Gender correlated with preferences in one study,41 but did not correlate in four.35 38 40 47 Possible correlations with living arrangement, education, employment-status and income level were investigated with negative or mixed results.

Severity of disease correlated with preferences for hypothetical health states43 47 and the impact of a side effect on utility.28 Two studies40 42 found that disease severity did not correlate with preferences, and one study reported mixed results.43

Comparison with other stakeholder groups

Eight studies, all on schizophrenia, compared the preferences of patients with those of other stakeholder groups.28 36 39 40 44–46 48 Patients’ preference values differed systematically from those of other stakeholders in the five studies published after 1997, and the magnitude of the differences varied from modest to considerable.28 36 40 44 45 People with schizophrenia valued disease states higher than other stakeholder groups did.28 40 44 Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) were given a lower value or deemed more important, compared to clinicians,28 44 45 except in one study.48 The preferences of family members were closer to those of patients, compared to psychiatrists and laypeople, in studies that performed relevant comparisons.28 44 48 Other stakeholders did not value functioning or symptoms significantly and/or consistently different from what patients did (see online supplementary appendix 8).

Strengths of preferences

Stated preference methods elicit different preference measures. WTP represents the value that an individual places on a commodity, SG and TTO estimate a utility, most often on a scale where 0 is death and 1 perfect health. CA and DCE measure the relative importance or value of different outcomes.19

Schizophrenia

‘Positive’, ‘acute’ or ‘psychotic’ symptoms figured consistently among the least desirable outcomes to patients.36 40 45 Negative symptoms such as reduced capacity for emotion were found more desirable or less important than positive symptoms.36 45 48

Independency was rated highly,36 45 and being an inpatient, lowly.48 Cognitive36 42 and social36 42 45 functions were moderately or highly important compared to other outcomes. The importance of capacity for work and for daily living was intermediate.36 42.45

EPS was included in seven studies. Two small studies39 46 both reported that the disutility of parkinsonism was larger than the disutility of akathisia and tardive dyskinesia. The presence of EPS reduced the utility by 12–21%. Pseudoparkinsonism reduced the utility with 5–7% in two other studies.28 44 In three additional studies the relative importance of EPS was moderate or high, compared to other outcomes.40 42 45 Health states with weight gain had a higher utility than states with EPS in the only schizophrenia study including side effects other than EPS.40

Depression

Severe, untreated depression reduced the utility from 1.0 (perfect health) to 0.3, and 25% of patients considered this state equivalent to or worse than death.47 Patients’ reduced ability to start and cope with activities on their own, due to fatigue, was more important than depressed mood in one large, well-performed study.35 The same study found that side effects after 2 weeks also were more important than depressed mood.35

The simultaneous presence of weight gain and no orgasm reduced the WTP from USD 686 per month for an antidepressant without side effects, to USD 227.41 One study found very small differences in side effect utilities.47 Patients were willing to pay more to avoid tremor and sleepiness than to avoid dry mouth and sweating, according to one study.38

Bipolar disorder

The inpatient state, inpatient mania and severe depression had lower utilities than the outpatient, stable state in one study.43 The relative strengths of preferences for mania versus depression were conflicting in two studies.34 43 Cognitive effect and severity of depression were equally important in one study.34

Weight gain within 3 months was found to be equally important to cognitive impairment and severity of depression, and three times more important than serious side effects34 A weight gain of more than 2.3 kg reduced the utility with 0.07.43

ADHD

Patients were willing to pay 74% more for functioning well in the morning and school/workday, compared to functioning well in the afternoon/evening in one study.37

Table 2 and online supplementary appendix 9 contain additional details on all the conditions.

Table 2.

Relative strengths of preferences

| Study | Condition | Outcomes | Results, patients’ preferences only |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morss et al39 | Schizophrenia | 3 side effects: akathisia, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism | 33 patients with chronic schizophrenia gave their preferences for three side effects, using VAS scales, PC and SG. 78% of the patients had at least one of the side effects themselves. The SG disutilities for the three side effects reduced the expected quality of life by 12–16%. The expected mean value of life for akathisia and for tardive dyskinesia using the SG method was 0.88, while parkinsonism reduced the value to 0.84. Patients reported parkinsonism to be the worst side effect, using VAS and PC. The VAS method yielded significantly lower values than the SG method |

| Revicki et al48 | Schizophrenia | 5 health states: (1) inpatient, acute positive symptoms, (2) outpatient, negative symptoms, (3) outpatient, moderate function, (4) outpatient, good function, (5) outpatient, excellent function | 49 patients with schizophrenia used CRS and PC. The patients had relatively little psychopathology and cognitive impairment. Five hypothetical health states were presented to the patients. In the SG, patients valued being hospitalised and having acute positive symptoms the lowest (0.19), followed by the outpatient state with negative symptoms (0.30), and outpatient with moderate (0.49), good (0.57) and excellent (0.77) function. SG utilities in the current study were significantly higher than the CRS preferences for all health states |

| Lenert et al46 | Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | 3 side effects: akathisia, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism | 22 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder used VAS, PC and SG methods. The same three side effects as in Morss 1993 were presented to patients. The SG disutilities for each of the three side effects reduced the expected quality of life by 13–21%. The expected mean value of life using the SG method was 0.87 for akathisia and 0.88 for tardive dyskinesia, and 0.79 for parkinsonism. Parkinsonism was rated the worst side effect using the VAS scale. The VAS method yielded significantly lower values than the SG methods |

| Lee et al44 | Schizophrenia | 2 patterns of mental health impairment (less severe/more severe), based on 4 dimensions and 1 side effect: hostility/suspiciousness, anxiety/depression, withdrawal/retardation and thought disorder, and pseudo-parkinsonism | 20 patients with schizophrenia were included in the study, which used VAS and SG methods. Less and more severe health states based on four “dimensions” were presented to patients. Pseudoparkinsonism reduced the average SG values with 0.07, and using VAS: 0.08. The utilities of the four dimensions were not reported |

| Lenert and Kaplan28 | Schizophrenia | 6 health states with different degrees of symptoms (mild or moderate levels), with or without pseudo-parkinsonism, based on four symptom domains: thought disorders and disorders of cognition, withdrawal (negative symptoms), anxiety/depression and hostility | 148 patients with schizophrenia from geographically and clinically diverse environments gave their preferences for hypothetical health states representing four symptom domains similar to those in Lee et al, using VAS and SG methods. The reduction in utility between states without and with pseudo-parkinsonism was found to be approximately 0.07 (SG) and 0.14 (VAS) for milder states, and 0.05 (SG) and 0.07 (VAS) for more severe states (values based on figure in original article). Mild disease symptoms with pseudoparkinsonism was equally preferable to moderate symptoms without side effects. VAS scores were systematically higher than SG scores were. The utilities of the four symptom domains were not reported. |

| Shumway45 | Schizophrenia | 16 health states including 7 outcomes: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, social function, independent living, vocational function | 50 patients with schizophrenia in an outpatient setting rated 16 health states using rating scales and CA. Preference weights for seven outcome domains were computed using a CA procedure. The highest mean preference weight was found for social function (16.9), followed by, in descending order, positive symptoms (15.0), independent living and tardive dyskinesia (both 14.5), vocational function (14.1), extrapyramidal symptoms (13.5) and negative symptoms (11.5). There were no statistically significant differences between the ranked preferences |

| Briggs et al40 | Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | 7 health states: stable disease, relapse and 5 side effects: weight gain, hyperprolactinaemia, diabetes, EPS and negative symptoms | 50 outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder rated health states directly on a preference assessment rating scale and then completed a TTO task for each health state. The highest mean utility was given to the stable schizophrenia state (0.92), followed by weight gain (0.83), hyperprolactinaemia (0.82), diabetes (0.77) and EPS (0.72). Relapse had the lowest mean utility (0.60) |

| Bridges et al36 | Schizophrenia | 20 treatment goals: decreased/increased depressive thoughts and feelings, cognition, satisfaction, performance, self-independence, physical health, psychotic symptoms, anxiety, social contacts, activities of daily living, capacity for work, self-confidence, family relationships, restlessness, visits to the doctor/hospital, improved communication, mistrust/hostility, irritability, capacity for emotion, sexual pleasure | 105 outpatients with schizophrenia ranked and rated 20 treatment goals in a self-explicated method study. The product of the ranking and rating (scale 0–100) revealed that decreased depressive thoughts and feelings was valued highest (58.5), followed by, in descending order, improved cognition (55.9), improved satisfaction (54.4), improved performance (52.6), improved self-independence (51.3), improved physical health (50.1), decreased psychotic symptoms (48.9), decreased anxiety (46.6), improved social contacts (45.3), improved activities of daily living (45.1), improved capacity for work (43.5), improved self-confidence (42.4), improved family relationships (38.9), decreased restlessness (36.9), decreased visits to the doctor/hospital (36.8), improved communication (35.9), decreased mistrust/hostility (31.9), decreased irritability (30.8), improved capacity for emotion (28.5) and improved sexual pleasure (24.2) |

| Kinter et al42 | Schizophrenia | 7 attributes, defined over 2 levels including: disease symptoms, relapse, clear thinking, social activities, extrapyramidal symptoms, daily activities, and support | 101 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia participated in this methodological study that compared two different CA designs. Seven patient-oriented attributes, each defined over two levels, were presented. The parameter estimate for the outcomes, using a D-efficient design, were in descending order, EPS (0.553), daily activities (0.522), support (0.451), social activities (0.364), clear thinking (0.332), relapse (0.196) and disease symptoms (0.107). All parameter estimates except disease symptoms were statistically significant within the model. Using the orthogonal design, EPS (0.756) and daily activities (0.623) also had the highest estimates, followed by clear thinking (0.454), support (0.446), social activities (0.313), and disease symptoms (0.269) and relapse (0.095). All parameter estimates except relapse were statistically significant within the model. The results of the two models were not statistically different |

| O'Brien et al38 | Mild or moderate depression | 7 side effects: blurred vision, tremor, sleepiness, dizziness, constipation, sweating, dry mouth | 95 patients with mild or moderate depression ranked and rated seven adverse effects. The maximum WTP per month (CAD) for a reduction in the incidence of each adverse effect was highest for blurred vision (21.9), followed by (in descending order) tremor (19.4), sleepiness (18.6), dizziness (16.8), constipation (15.8), sweating (13.9) and dry mouth (11.4). There was a statistically significant difference between the two extremes of blurred vision and dry mouth |

| Revicki 47 | Major depressive disorder | 11 health states, with varying depression severity, functioning and well-being, medication treatment, 8 side effects | Utilities for 11 hypothetical health states from 70 patients with major depressive disorder were obtained in this VAS and SG study. Severe, untreated depression had the lowest mean utility (0.30). 25% rated this state as worse or equivalent to death. The highest score was found for remission and no treatment (0.86), followed by depression in remission and maintenance treatment (0.72–0.83). The observed mean differences in utility for side effects compared to their absence ranged from 0.12 points for nervousness and light-headedness, to 0.01 points for dry mouth and nausea. Point values for sedation, headache, constipation and tension were not reported. The only side effect showing a statistically significant reduction in utility when present was light-headedness |

| Morey et al41 | Major depressive disorder | Different treatment characteristics presented in 40 states (20 choice pairs) varying the treatment characteristics of effectiveness, side effects (weight gain, little or no interest in sex, inability to achieve orgasm), money costs, hours of psychotherapy per month and use of antidepressants | 104 patients with major depressive disorder were included in the study. Using a willingness to pay (WTP) approach, treatment characteristics were varied in 20 different choice-pairs presented to patients. The monthly expected WTP was highest for “antidepressants with no side effects” and the combined treatment of “anti-depressants and 2 hrs therapy” (both $686 for a RI). WTP decreased if the antidepressant treatment had the side effect of no orgasm (WTP for an RI $478), weight-gain of 5% (WTP for an RI $409) or both these side effects (WTP for an RI $227) |

| Zimmermann et al35 | Depression | 18 hypothetical treatment outcome scenarios, differing in 8 attributes: depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, loss of energy/fatigue, sleep disturbance, feelings of guilt, depression-related pain, treatment duration, side effects after 2 weeks | 227 patients with self-reported depression, currently or recently on antidepressants, used a choice-based conjoint analysis. 18 pairs of hypothetical treatment outcome scenarios differing on 8 attributes were presented. Loss of energy/fatigue was the most important outcome attribute (relative importance 18.5%), differing significantly from all other attribute importance values. The relative importance of side effects after 2 weeks was 14.2%, loss of interest and enjoyment 13.5%, depression-related pain 12.0%, sleep disturbance 12.0%, feelings of guilt 11.5% and duration of treatment 9.9%. Least importance was assigned to depressed mood: 8.5%. The factor levels most strongly affecting the utility scores for “loss of energy/fatigue” were “Can start and cope with all activities on his/her own” (utility score + 10.9) and “Cannot start or cope with any activities on his/her own” (-11.7). The factor level most strongly affecting the utility of “loss of interest and enjoyment” was “Has no interest in previous leisure activities” (-10.0). Standard deviations were given for factor levels but not for the attributes |

| Revicki et al43 | Bipolar disorder I | 55 health states differing in side effects, symptom severity, functioning, well-being and mono-/combination therapy | 96 patients in a VAS and SG study were presented hypothetical health states describing combinations of symptom severity, functioning, well-being and side effects. Mean utilities (0 anchored as death, 1 anchored as complete health) were calculated for inpatient states (0.12–0.33), inpatient mania states (0.23–0.26), severe depressive state (0.29), outpatient mania states (0.29–0.64), stable tardive dyskinesia (0.76) outpatient stable states with few clinical symptoms and no weight gain (0.58–0.83). A weight gain of more than 2.3 kg demonstrated an average 0.066 decrease in health state utilities. Patients preferred mono-therapy to combination therapies. The difference for weight gain was statistically significant. The difference in utilities for the outpatient and inpatient mania state was not statistically significant |

| Johnson et al34 | Bipolar disorder | 8 medication attributes including: frequency and severity of mania or depression episodes, side effects such as weight gain, cognitive deterioration, fatigue and the risk of developing an unspecified, but potentially life-threatening, side effect | 469 patients in a DCE gave their importance weights for eight medication attributes. Patients considered weight gain within 3 months to be most important (0.20), followed by cognitive impairment (0.185) and changes in the severity of depression (0.184). These outcomes were statistically significantly more important than a fatigue effect (0.11), mania severity (0.09), mania frequency (0.08), depression frequency (0.08) and risk of serious side effects (0.06). The values are approximate and based on the figures in the original article |

| Glenngård et al37 | ADHD | 5 health states: health state morning/workday (effectiveness), health state afternoon/early evening (effectiveness), side effects, dosing frequency per day, and price (cost of treatment per month) | 116 patients, all currently on ADHD, participated in DCE, presenting a combination of five hypothetical medication attributes, including attribute levels. Functioning in the morning and during school/workday was most important (WTP per month 252), followed by functioning during the afternoon/evening (WTP 145), number of dosages per day (WTP -43) and side effects (WTP -98) |

CA, conjoint analysis; CRS, categorical rating scale; DCE, discrete choice experiment; PC, pairwise comparison; RI, representative individual; SG, standard gamble; TTO, time trade-off; VAS, visual analogue scale; WTP, willingness to pay.

Discussion

Principal findings

Benefits to patients and clinical practice were part of the purpose in a minority of the 16 studies included in this review. Most authors had not involved patients when they selected and developed the outcomes in their studies. Side effect and symptom outcomes outnumbered functioning and process outcomes, and only a limited selection of potentially important outcomes were presented to patients. The stated preference methods were generally found to be feasible across different conditions and disease severities, but patients with schizophrenia experienced more problems with the tasks than other patient groups, in particular for SG. The patients’ preferences did not vary consistently with age, gender, disease severity or other demographic or disease variables. The relative preferences of patients with schizophrenia differed systematically from those of other stakeholders in most studies. Patients valued disease states higher than did other groups and perceived side effects more negatively than clinicians did. Patients with schizophrenia desired acute and psychotic symptoms least of all outcomes, and valued independency highly. Functioning occupied a middle ground; social function tended to be more important than vocational function. The importance of EPS was moderate or high. For patients with depression, severe disease greatly reduced utility, though the ability to cope with activities, and presence of side effects, appeared more important than a depressed mood, per se. Patients with bipolar disorder valued inpatient mania and severe depression lowly, and reported weight gain to be important. In ADHD, patients reported that functioning in the morning and during daytime was most important.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

This is the first systematic review on patients’ relative, stated preferences for outcomes of psychopharmacological treatments across methods and disorders. The review accords with the PRISMA guidelines (see online supplementary appendix 10) and the protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database prior to conduction (see online supplementary appendix 11).

We summarised patients’ preferences for outcomes associated with medications and excluded preferences for specific medications or treatment domains, which are amenable to misconceptions. The treatments do not give value to the user, per se; it is their outcomes that give value.49 In a trade-off situation, the best option reflects the partial valuations and probabilities of those outcomes.50

Preference studies are not archived in reference databases with common subject headings and keywords that allow a highly sensitive and specific retrieval.25 We tested and applied a broad, peer reviewed search strategy, but we might have overlooked or missed studies.

We rigorously and comprehensively assessed study quality. Several included studies risked multiple biases and stricter criteria could have been applied. However, quality criteria for preference studies can conflict and methodological rigour must be balanced with the cognitive effort demanded from participants.

Owing to the heterogeneity of methods and outcomes, we could not perform quantitative summaries of the relative strengths of preferences, as is common in systematic reviews on preference studies.26 51 52 Our review includes studies that were not powered to provide statistically significant differences for strengths of preferences. Preferences for outcomes were elicited from varying and often small numbers of participants, with heterogeneous disorders.

The end of the search period was September 2013, thus at the time of publication the search is relatively old in comparison to the median for systematic reviews.53 54

Stated preference studies elicit preferences in hypothetical choices, and the outcome preferences in a real setting might be different. The reliability and validity of specific patient preference methods is debated, and the techniques and quality standards are likely to change in the future.21 55 56

Results in context

The call for outcomes that are meaningful and important to patients is increasing57 58 Patient-centred outcomes are often contrasted to clinical outcomes such as symptom control and side effects. They assess the impact of illness and therapy from patients’ perspectives, and should be those that patients notice and care about.59

In contrast to this aim, we found that outcomes presented for preference elicitation were mostly selected and described without input from patients. Other systematic reviews on stated preferences confirm this finding. In a review of experiences of healthcare delivery, few outcomes were worded from patients’ perspectives.21 In a review on diabetes care, only 3 of 14 studies had employed focus groups in the outcome selection process.52 Disease-specific reviews often do not report on patient involvement.26 51 60 In line with this lack of patient-centredness and similar to our findings, symptom outcomes and adverse effects are most frequently included in preference studies, at the expense of other outcomes.25

Suggested patient-centred outcomes in mental disorders include social and vocational functioning, body image, reduced stigma, recovery and reduced burden to caregivers.22 In schizophrenia alone, 194 non-traditional outcomes have been suggested.61 We found that side effects and in particular EPS and weight gain were important to patients, both relative to other outcomes and to other stakeholders. Side effects have an impact on health status, but to patients, their effect on physical attractiveness and the associated status, self-esteem and social opportunity might be more important.62 When the functional consequences of adverse events and no treatment are similar, people value avoiding the adverse effects most.51

In addition to side effects, severe symptoms were highly important to patients, whereas functioning was moderately important. The claim that patients value functioning higher than symptom-oriented, ‘textbook’ outcomes, was therefore not supported.36

We found significant differences in how patients and non-patients valued outcomes. This topic is currently debated. Accordant with our findings, the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date63 concluded that patients value health states higher than the general public. The difference was small to moderate, and notably the valuations differed less when both groups valued descriptions of health states, instead of patients valuing their actual health. A possible explanation for a difference is that people adapt when they become ill: we develop skills, adjust activities and expectations, and redefine what is good health and a good life.55 64 65 Notably, different valuations of one-dimensional health states do not necessarily translate to differing partial utilities of health states and to process outcomes.66

Concerns have been raised that cognitive impairment, limited self-insight and distortions of reality impede patients’ use of stated preferences methods, and could leave the results meaningless, in particular in schizophrenia.67 68 The results of the studies in this review indicate that several stated preference methods might be feasible for identifying relative outcome preferences from patients with mental disorders, and that validity is comparable to other stakeholder groups. In a systematic review, the practicality of TTO and CV (contingent valuation) was found to be generally good in patients with depression and schizophrenia. Two of the four studies in the review reported that patients with schizophrenia had some difficulties with the SG tasks.69 The need to improve the techniques persists.70

Meaning of study

Patients report that being told the risks and benefits of treatments is one of the 10 most important aspects of healthcare.71 However, which risks and benefits clinicians communicate to patients is a matter of choice. This review highlights outcomes and outcome priorities clinicians should consider bringing into their conversations with patients when they discuss and decide between psychotropic drug options.

Our findings could inform on the benefits and harms to include in patient decision aids, which are tools designed to help patients participate in making choices among healthcare options.72

It has been suggested that authors of clinical guidelines should conduct a systematic review on patient preferences in the relevant content area.28 51 The stated preferences presented in this review could be used as an early point of reference when guidelines are developed for schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder and ADHD.

In situations where stakeholder groups have different values, spotlighted in this review, a main question is whose preferences should be accommodated? Proponents of the patients’ preferences argue that people with the relevant disease are the best judges of their own welfare, and that true preferences require experience with the outcome. Opponents claim that the judgments of non-patients are more appropriate, because decisions affecting resource allocation for one group of patients affect the provision for other groups.55 The dilemma is not empirical, but normative, and the answer depends on the decision context.55 73

In economic assessments, the relative preferences from patients reported in this review might inform regulatory benefit-risk assessments and be used in direct comparisons of drugs,9 but in this field, the preferences of the general population is currently the norm.74

Unanswered questions and implications for research

Although many studies have addressed ‘what matters’ to patients with mental disorders, few have investigated the relative preferences for medication outcomes. Current knowledge is fragmented and exists for a limited number of aspects and conditions only. Surprisingly, only a minority of the studies have been performed from patients’ perspectives. The evidence does not allow firm conclusions on what outcomes of psychotropic medications matter most to patients, and there is an obvious need for more research.

Insufficient reporting in stated preference studies is widespread.51 52 60 Concise reporting of all study dimensions, including variance, study design and the outcome descriptions presented to patients, is necessary. Although the studies in this review generally found that stated preference methods were feasible for patients with mental health disorders, challenges were also exposed, demonstrating that the techniques need to be improved and tailored to the relevant populations.

Conclusion

Despite the widely declared prominence of patient preferences in healthcare, knowledge on which medication-related outcomes matter most to patients with mental health disorders has been largely absent. Clinicians and policymakers should be aware that patients’ priorities might be different from theirs and that they cannot reliably be inferred from patients’ demographic characteristics or health status. To improve health outcomes for patients, we need more evidence on the relative importance patients place on relevant outcomes. In clinical practice, knowledge on group-level preferences can be a starting point, but to know what matters most to the person in front of you, you have to ask.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the helpful insights provided by Jack Dowie.

Footnotes

Contributors: OE was involved in study design, systematic search, pilot of data extraction form, title/abstract scanning, determining eligibility of articles, quality assessment of articles, data extraction, data synthesis, data interpretation, literature search, and writing and revising paper and appendices. BFL was involved in title/abstract scanning, determining eligibility of articles, obtaining full text and revising manuscript. EA was involved in systematic search, writing the article and see online supplementary appendix 2. MN was involved in study design, data synthesis, data interpretation and revising the manuscript. GS was involved in study design, determining eligibility of articles, quality checks of included articles and appendices, and revising the paper. KN was involved in study design, title/abstract scanning, pilot of data extraction form, determining eligibility of articles, quality assessment of articles, data extraction, data synthesis/analysis, data interpretation, literature search, and writing and revising the paper and appendices. All authors had full access to the data, approved the final draft, and take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis and the integrity of the data. OE and KN are guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, and the Sykehuset Innlandet Hospital Trust, Norway. The work was undertaken by the Evicare (Evidence-based care processes) research and innovation project partnership (http://www.kunnskapssenteret.no/prosjekter/evicare-evidence-based-care-processes-integrating-knowledge-in-clinical-information-systems).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Full data sets and technical appendices are available with open access from corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Crossing the Quality Chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. USA: The Institute of Medicine, 2001. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picker H. Moving beyond measurement. Oxford, UK: Picker Institute Europe, 2012/13. http://www.pickereurope.org/assets/content/pdf/Annual_Reviews_&_Financial_Statements/2012–13%20Annual%20Review%20FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.IAPO. What is Patient-Centred Healthcare? A review of Definitions and Principles. International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations (IAPO), 2004:37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71–2. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AGREE. Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. The AGREE Collaboration, 2001. http://apps.who.int/rhl/agreeinstrumentfinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci 2009;4:75 10.1186/1748-5908-4-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Facey K, Boivin A, Gracia J et al. Patients’ perspectives in health technology assessment: a route to robust evidence and fair deliberation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2010;26:334–40. 10.1017/S0266462310000395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breckenridge A. Patient opinions and preferences in drug development and regulatory decision making. Drug Discov Today Technol 2011;8:e1–e42. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egbrink M, IJzerman M. The value of quantitative patient preferences in regulatory benefit-risk assessment. J Mark Access Health Policy [S.l.] Apr 2014. http://www.jmahp.net/index.php/jmahp/article/view/22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall D. A Radical Idea: Make Patient Preferences an Integral Part of Health Care. The Official News & Technical Journal of The International Society For Pharmacoeconomics And Outcomes Research, 2012–2013. http://www.ispor.org/News/articles/Jan-Feb2013/presidents-message.asp (accessed 5 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 11. America's state of mind: Medco Health Solutions, Inc., 2001–2010. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19032en/s19032en.pdf.

- 12.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S et al. Psychotropic drug utilization in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:772–85. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker RG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology 2012;17:776–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382:951–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD et al. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:595–602. 10.4088/JCP.12r07757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swift JK, Callahan JL. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 2009;65:368–81. 10.1002/jclp.20553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelhorn HL, Sexton CC, Classi PM. Patient preferences for treatment of major depressive disorder and the impact on health outcomes: a systematic review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2011;13:PCC.11r01161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–186. 10.3310/hta5050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bridges JF. Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: an emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003;2:213–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan M, Kinghorn P, Entwistle VA et al. Valuing patients’ experiences of healthcare processes: towards broader applications of existing methods. Soc Sci Med 2014;106:194–203. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green CA, Estroff SE, Yarborough BJ et al. Directions for future patient-centered and comparative effectiveness research for people with serious mental illness in a learning mental health care system. Schizophr Bull 2014;40(Suppl 1):S1–94. 10.1093/schbul/sbt170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan PF, Strombom I. Improving health care by understanding patient preferences: the role of computer technology. JAMIA 1998;5:257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bridges JF, Onukwugha E, Johnson FR et al. Patient preference methods—a patient-centered evaluation paradigm. ISPOR Connections 2007;13:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opmeer BC, de Borgie CA, Mol BW et al. Assessing preferences regarding healthcare interventions that involve non-health outcomes: an overview of clinical studies. Patient 2010;3:1–10. 10.2165/11531750-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umar N, Yamamoto S, Loerbroks A et al. Elicitation and use of patients’ preferences in the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:341–6. 10.2340/00015555-1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Review of stated preference and willingness to pay methods. London: Accent and RAND Europe, 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.competition-commission.org.uk/our_role/analysis/summary_and_report_combined.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenert L, Kaplan RM. Validity and interpretation of preference-based measures of health-related quality of life. Med Care 2000;38(9 Suppl):Ii138–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AERA A, NCME. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: AERA Publication Sales, 2000. http://www.apa.org/science/programs/testing/standards.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares M, Dumville JC. Critical appraisal of cost-effectiveness and cost-utility studies in health care. Evid Based Nurs 2008;11:99–102. 10.1136/ebn.11.4.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008:187–241. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akers J. Systematic Reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, 2009. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Manjunath R et al. Factors that affect adherence to bipolar disorder treatments: a stated-preference approach. Med Care 2007;45:545–52. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318040ad90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmermann TM, Clouth J, Elosge M et al. Patient preferences for outcomes of depression treatment in Germany: a choice-based conjoint analysis study. J Affect Disord 2013;148:210–19. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridges JF, Slawik L, Schmeding A et al. A test of concordance between patient and psychiatrist valuations of multiple treatment goals for schizophrenia. Health Expect 2013;16:164–76. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00704.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glenngård AH, Hjelmgren J, Thomsen PH et al. Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for ADHD treatment with stimulants using discrete choice experiment (DCE) in Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Nord J Psychiatry 2013;67:351–9. 10.3109/08039488.2012.748825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Brien BJ, Novosel S, Torrance G et al. Assessing the economic value of a new antidepressant. A willingness-to-pay approach. PharmacoEconomics 1995;8:34–45. 10.2165/00019053-199508010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morss SE, Lenert LA, Faustman WO. The side effects of antipsychotic drugs and patients’ quality of life: patient education and preference assessment with computers and multimedia. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1993:17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs A, Wild D, Lees M et al. Impact of schizophrenia and schizophrenia treatment-related adverse events on quality of life: direct utility elicitation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:105 10.1186/1477-7525-6-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morey E, Thacher JA, Craighead WE. Patient preferences for depression treatment programs and willingness to pay for treatment. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2007;10:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinter ET, Prior TJ, Carswell CI et al. A comparison of two experimental design approaches in applying conjoint analysis in patient-centered outcomes research: a randomized trial. Patient 2012;5:279–94. 10.1007/BF03262499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revicki DA, Hanlon J, Martin S et al. Patient-based utilities for bipolar disorder-related health states. J Affect Disord 2005;87:203–10. 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee TT, Ziegler JK, Sommi R et al. Comparison of preferences for health outcomes in schizophrenia among stakeholder groups. J Psychiatr Res 2000;34:201–10. 10.1016/S0022-3956(00)00009-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shumway M. Preference weights for cost-outcome analyses of schizophrenia treatments: comparison of four stakeholder groups. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:257–66. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenert LA, Morss S, Goldstein MK et al. Measurement of the validity of utility elicitations performed by computerized interview. Med Care 1997;35:915–20. 10.1097/00005650-199709000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Revicki DA, Wood M. Patient-assigned health state utilities for depression-related outcomes: differences by depression severity and antidepressant medications. J Affect Disord 1998;48:25–36. 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revicki DA, Shakespeare A, Kind P. Preferences for schizophrenia-related health states: a comparison of patients, caregivers and psychiatrists. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;11:101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Pol Econ 1966;74:132–57. 10.1086/259131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riabacke M, Danielson M, Ekenberg L.2012. Review Article State-of-the-Art Prescriptive Criteria Weight Elicitation. http://downloads.hindawi.com/journals/ads/2012/276584.pdf.

- 51.Maclean S, Mulla S, Akl EA et al. Patient values and preferences in decision making for antithrombotic therapy: a systematic review: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e1S–e23S. 10.1378/chest.11-2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arx L-B, Kjær T. The patient perspective of diabetes care: a systematic review of stated preference research. Patient 2014;7:283–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beller EM, Chen JK-H, Wang UL-H et al. Are systematic reviews up-to-date at the time of publication? Syst Rev 2013;2:36 10.1186/2046-4053-2-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shojania G, Sampson M, Ansari MT et al. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 2007;147:224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stamuli E. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: who should value health? Br Med Bull 2011;97:197–210. 10.1093/bmb/ldr001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Özdemir SJFR. Estimating willingness to pay: do health and environmental researchers have different methodological standards? Appl Econ 2013;45:2215–29. 10.1080/00036846.2012.659345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hampson M, Killaspy H, Mynors-Wallis L et al. Outcome measures recommended for use in adult psychiatry. R College Psych 2011. (OP78). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gartlehner G, Flamm M. Is The Cochrane Collaboration prepared for the era of patient-centred outcomes research? Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:ED000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hickam D, Totten A, Berg AR et al. , eds. The PCORI Methodology Report. USA: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, 2013: Appendix A. http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/11/PCORI-Methodology-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wortley S, Wong G, Kieu A et al. Assessing stated preferences for colorectal cancer screening: a critical systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient 2014;7:271–82. 10.1007/s40271-014-0054-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vieta A, Badia X, Álvarez E et al. Which nontraditional outcomes should be measured in healthcare decision-making in schizophrenia? A systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2012;48:198–207. 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2011.00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seeman MV. Antipsychotics and physical attractiveness. Clini schizophr Relat Psychoses 2011;5:142–6. 10.3371/CSRP.5.3.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peeters Y, Stiggelbout AM. Health state valuations of patients and the general public analytically compared: a meta-analytical comparison of patient and population health state utilities. Value Health 2010;13:306–9. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krabbe PF, Tromp N, Ruers TJ et al. Are patients’ judgments of health status really different from the general population? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:31 10.1186/1477-7525-9-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barclay-Goddard R, King J, Dubouloz CJ et al. Building on transformative learning and response shift theory to investigate health-related quality of life changes over time in individuals with chronic health conditions and disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:214–20. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neuman T, Neuman E, Neuman S. Explorations of the effect of experience on preferences for a health-care service. J Socio-Econ 2010;39:407–19. 10.1016/j.socec.2010.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shumway M, Sentell T, Chouljian T et al. Assessing preferences for schizophrenia outcomes: comprehension and decision strategies in three assessment methods. Ment Health Serv Res 2003;5:121–35. 10.1023/A:1024415001045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voruganti LN, Awad AG, Oyewumi LK et al. Assessing health utilities in schizophrenia. A feasibility study. Pharmacoeconomics 2000;17:273–86. 10.2165/00019053-200017030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Konig HH. Measuring preferences of psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Prax 2004;31:118–27. 10.1055/s-2003-812598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Flood C. Should “standard gamble” and “‘time trade off” utility measurement be used more in mental health research? J Ment Health Policy Econ 2010;13:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robert G, Cornwell J, Brearley S et al. What matters to patients? Developing the evidence base for measuring and improving patient experience. Coventry, UK: The Department of Health and NHS Institute for Innovation & Improvement and King's College London, 2011:1–200. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images/Patient_Experience/Final%20Project%20Report%20pdf%20doc%20january%202012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Wit GA, Busschbach JJ, De Charro FT. Sensitivity and perspective in the valuation of health status: whose values count? Health Econ 2000;9:109–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk/media/D45/1E/GuideToMethodsTechnologyAppraisal2013.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]