Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the differences of clinical features, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), MRI findings and response to steroid therapies between patients with optic neuritis (ON) who have myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies and those who have seronegative ON.

Setting

We recruited participants in the department of neurology and ophthalmology in our hospital in Japan.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated the clinical features and response to steroid therapies of patients with ON. Sera from patients were tested for antibodies to MOG and aquaporin-4 (AQP4) with a cell-based assay.

Participants

Between April 2009 and March 2014, we enrolled serial 57 patients with ON (27 males, 30 females; age range 16–84 years) who ophthalmologists had diagnosed as having or suspected to have ON with acute visual impairment and declined critical flicker frequency, abnormal findings of brain MRI, optical coherence tomography and fluorescein fundus angiography at their onset or recurrence. We excluded those patients who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of neuromyelitis optica (NMO)/NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD), MS McDonald's criteria, and so on. Finally we defined 29 patients with idiopathic ON (14 males, 15 females, age range 16–84 years).

Results

27.6% (8/29) were positive for MOG antibodies and 3.4% (1/29) were positive for AQP4. Among the eight patients with MOG antibodies, five had optic pain (p=0.001) and three had prodromal infection (p=0.179). Three of the eight MOG-positive patients showed significantly high CSF levels of myelin basic protein (p=0.021) and none were positive for oligoclonal band in CSF. On MRIs, seven MOG-positive patients showed high signal intensity on optic nerve, three had a cerebral lesion and one had a spinal cord lesion. Seven of the eight MOG-positive patients had a good response to steroid therapy.

Conclusions

Although not proving primary pathogenicity of anti-MOG antibodies, the present results indicate that the measurement of MOG antibodies is useful in diagnosing and treating ON.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cohort illuminates the characteristics of autoimmune optic neuritis (ON) with antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG).

Of 29 patients with idiopathic ON, 27.6% were positive for MOG antibodies.

The measurement of MOG antibodies by cell-based assay was useful in diagnosing autoimmune ON.

The patients with MOG-positive ON had a good response to steroid therapy.

A limitation of this study was that the sample size was small, so a prospective multicentre study is needed.

Introduction

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) is detected mainly at the extracellular surface of myelin sheaths and oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system,1 and autoantibodies against MOG are found in patients with paediatric multiple sclerosis (MS), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and neuromyelitis optica (NMO).2–5 In 2013, a study by Sato et al6 that included MOG antibody-positive patients among their patients with NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD), described optic neuritis (ON) or longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) with three or more vertebral segment spinal cord lesions observed on MRI. Sato et al6 also reported that males predominated (0.6:1.0) in the patients with MOG antibodies. Tanaka and Tanaka7 reported that 75% of MOG antibody-positive patients (three of four patients who were also negative for aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies) had optic nerve lesions, and Kezuka et al8 showed a relationship between NMO antibody and MOG antibody in ON and visual outcomes. Some recent case reports also showed ON with serum MOG antibodies,8 but there are no detailed reviewed data for idiopathic ON that include the epidemiology, prodromal infection, serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, and MRI findings.

In the present study, we reviewed some new findings regarding idiopathic ON with and without MOG antibodies, by examining a series of patients with ON at the acute phase and excluding patients with NMO/NMOSD, MS and other diseases.

Methods

Patients and samples

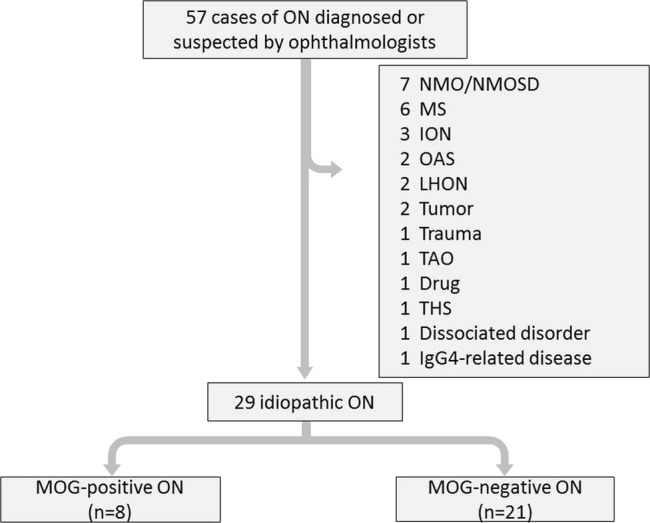

Between April 2009 and March 2014, we enrolled serial 57 patients with ON (27 males, 30 females; age range 16–84 years) who ophthalmologists had diagnosed as having or suspected to have ON with acute visual impairment and declined critical flicker frequency, abnormal findings of brain MRI, optical coherence tomography and fluorescein fundus angiography at their onset or recurrence at Nagasaki University Hospital, Japan. We excluded the patients who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of NMO/NMOSD,9 MS McDonald's criteria,10 ischaemic optic neuropathies, orbital apex syndromes, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathies, tumours, trauma, thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy, pentazocine and alcohol-induced, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, dissociated disorder and IgG4-related disease. Finally, we defined 29 patients with idiopathic ON as the study cohort (figure 1), and we retrospectively reviewed their clinical symptoms and results of their CSF examination, MRI studies and response to steroid therapies. We used ELISA for myelin basic protein (MBP) analysis, of which the cut-off level was 102 pg/mL. We prepared a standard protocol of steroid pulse therapy: methylprednisolone (mPSL) 1 g/day for three consecutive days per week for 1–5 weeks. We defined the terms to evaluate the responsiveness to steroid pulse therapies in the acute phase (before other treatments; eg, plasma exchange, fingolimod); ‘complete’ meant recovery to the patients’ original visual acuities, ‘good’ meant recovery to more than half of their original visual acuities, ‘not good’ meant less than ‘good’ within 1–5 courses of mPSL pulse therapies. All of the sera samples were obtained from the patients in an acute phase at their onset or recurrence. The range of follow-up period was 3–53 months (see online supplementary table).

Figure 1.

Patient enrolment flow chart. Ophthalmologists diagnosed ON with the disturbance of optic acuity, visual field, critical flicker frequency (CFF), brain MRI, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein fundus angiography. ION, ischaemic optic neuropathy; LHON, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMO, neuromyelitis optica; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders; OAS, orbital apex syndrome; ON, optic neuritis; TAO, thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy; THS, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein.

Antibody assays

We transfected a full-length human MOG cDNA expression vector (kindly gifted by Prof Markus Reindl) into 293 cells of human embryonic kidney (HEK) using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Cell cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Twelve hours after transfection, the HEK cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with 10% goat serum/PBS; the cells were incubated with patient sera (dilution, 1:10) in 0.02% Triton X-100/10% goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature followed by fluorescein isocyanate-conjugated antihuman IgG (dilution 1:50; DAKO Denmark, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 h. SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) was then applied to the slides, which were stained and observed using a fluorescence microscope (AxioVision, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany).

Serum anti-AQP4 IgG antibody levels were analysed using a previously reported indirect immunofluorescence assay of HEK-293 cells transfected with an expression vector containing human AQP4 M23 cDNA.7 The examiner (KT) of the anti-MOG and anti-AQP4 antibodies was blinded to all clinical data, including the clinical phenotype.7

Statistical analysis

We analysed the differences in categorical data between the group of patients with ON with MOG antibodies and the seronegative ON group using the Microsoft Excel 2010 t test, and p values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Patients

Of the 57 serial ON or suspected patients with ON, we excluded other demyelinating disorders (see figure 1) and enrolled 29 patients with idiopathic ON (14 males, 15 female, age range 16–84 years). Eight (two male, six female) of the 29 patients with ON (27.6%) were positive for MOG antibodies, and one patient was double-positive for MOG and AQP4 (table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features, antibodies and CSF data, MRI findings and outcome of steroid therapy in idiopathic ON

| MOG antibodies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n=21) | Positive (n=8) | p Value | |

| Total | 21 (72.4%) | 8 (27.6%) | – |

| Male:female | 12:9 | 2:6 | 0.130 |

| Age | |||

| Range | 22–84 | 16–65 | – |

| Median | 51.0 | 31.0 | 0.052 |

| Prodromic infection | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.179 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (19.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.689 |

| Autoimmune disorders | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.821 |

| Malignancy | 4 (19.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.734 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Visual disturbance | 21 (100%) | 8 (100%) | – |

| Optic pain | 2 (9.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 0.001 |

| Serum AQP4 antibodies | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.106 |

| CSF examination | |||

| Pleocytosis (>5/μL) | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.179 |

| MBP high level (>102 pg/mL) | 0 (0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.021 |

| Oligoclonal band | 1 (5.2%) (n=19) | 0 (0%) | 0.527 |

| Abnormal intensity on MRI | |||

| Optic nerve | 14 (66.7%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.278 |

| Cerebrum | 7 (33.3%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.840 |

| Spinal cord | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.106 |

| Therapies in acute phase | |||

| Steroid pulse | 17 (80.9%) | 8 (100%) | 0.196 |

| Oral prednisolone | 3 (14.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.262 |

| Plasma exchange | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.106 |

| Good or complete response to steroid therapy: | 17 (81.0%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.870 |

| Recurrence | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.512 |

Oral prednisolone; 20 mg/day.

AQP4, aquaporin-4; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MBP, myelin basic protein; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; ON, optic neuritis.

Demographic and clinical data

The median age of the eight MOG antibody-positive patients was 31 years, which is marginally younger than that of the patients with ON without MOG antibodies, 51 years (p=0.052). Five of the eight patients had optic pain (p=0.001), three had prodromal infection (p=0.179, table 1) and two had bilateral ON (see online supplementary table).

Two of the eight patients with MOG antibodies (25.0%) were positive for antinucleotide antibodies, compared to only three of the 18 seronegative patients with ON (16.6%). One patient had thyroid peroxidase antibodies, one had thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies and one had glomerular basement membrane antibodies; all had no neurological symptoms except for ON. All eight of the MOG antibody-positive patients were negative for oligoclonal band (OCB) in CSF, and only one seronegative ON patient was positive (5.5%, 1/18). In addition, 37.5% (3/8) of the patients with ON with MOG antibodies indicated significant positivity for MBP in CSF, as did 5.5% (1/18) of the seronegative patients with ON (p=0.021, table 1). The CSF cell count was not significantly different between the MOG-positive and MOG-negative ON groups (p=0.179).

Seven of the eight patients with ON with MOG antibodies without active underlying disease showed complete response to steroid pulse therapy. Although only one ON patient (patient 4, online supplementary table) with MOG antibodies emerged with myelitis at her third recurrence after 12 months from onset and had received plasma exchange, no one in the seronegative ON group exhibited myelitis (p=0.106). After her third recurrence, we prescribed fingolimod according to MS therapy, but she suffered from left optic pain and visual disturbance 19 days later, and thus we immediately stopped the fingolimod treatment. The single patient with AQP4 and MOG antibodies, who had gastric cancer, showed complete response following steroid therapy, in comparison to a previous report.8 The median follow-up period for patients with MOG antibodies was 26.5 months (range 3–53 months), 23 months (range 3–53 months) for monophasic patients and 30 months (range 22–52 months) for relapsed patients (see online supplementary table).

MRI

All 29 idiopathic patients with ON had undergone a brain and/or spinal MRI in their acute phase. We focused on three lesions (optic nerve, cerebrum and spinal cord) and evaluated the abnormal intensities between the patients with ON with MOG antibodies and those without MOG antibodies. We found that 66.7% (14/21) of the patients without MOG antibodies showed high intensities on T2-weighted images (T2WI) in their optic nerves, as did 87.5% (7/8) of the MOG-positive patients (p=0.278). We detected high intensities in the cerebrum of 33.3% (7/21) of the MOG-negative patients and in 25.0% (2/8) of the MOG-positive patients (p=0.840), and high intensities in the spinal cord in 0% (0/8) and 12.5% (1/8) of these patients, respectively (p=0.106). Regarding patient 4, T2WI on spinal MRI showed high signal on the vertebral level of Th11 and Th12 segmentally and did not show LETM.

Discussion

We have reported the detailed clinical features of serial patients with ON with MOG antibodies. Similar to previous reports, we observed that the patients with ON with MOG antibodies were marginally younger than those without MOG antibodies, as in other autoimmune diseases (p=0.052). Optic pain was a significant symptom for our MOG-positive idiopathic patients with ON (p=0.001). Unlike MS, no ON patient with MOG antibodies showed positivity for CSF OCB. In addition, our patients with ON with MOG antibodies showed significantly high levels of CSF MBP compared to those of the seronegative patients with ON (p=0.021).

Myelitis was not frequently observed among the present idiopathic patients with ON with MOG antibodies, compared to a previous report.11 We suspect that the optic nerve is sensitive to MOG antibodies and that MOG antibodies cause demyelination by some immunological mechanisms, resulting in swelling and optic pain; steroid therapies might thus be effective. In the present series of patients, the swelling and high signals on MRI T2WI of optic nerves were decreased after steroid therapy. The patient with gastric cancer who was double-positive for AQP4 and MOG antibodies achieved a complete response to steroid therapy, but another patient (patient 6, online supplementary table) who had autoimmune disease, showed no response to steroid therapy, as described previously.8 12 Except for the above patient, the optic pain and visual acuity of our MOG-positive patients improved completely, but there was no significant difference in the clinical outcomes at the end of steroid pulse therapies between the patients with idiopathic ON with MOG antibodies and those without MOG antibodies (p=0.870). When selecting a drug for the prevention of ON recurrence, we should deliberate and choose it based on neurological symptoms, the results of serum AQP and MOG antibody tests, and the CSF MBP level. It is possible that some immunosuppressants induce a recurrence of idiopathic ON with MOG antibodies.

Conclusions

MOG is considered a target antigen in some demyelinating disorders, and MOG antibodies cause demyelination and ON,13 similar to the pathogenesis of MS.14 When clinicians encounter a patient with idiopathic ON, the patient's CSF, MRI, serum AQP4 antibodies and MOG antibodies, might be useful to diagnose and treat.

Footnotes

Contributors: HN extracted and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. MM designed the experiment. KT examined the anti-MOG and anti-AQP4 antibodies. AF, as an ophthalmologist, diagnosed the ON. RN, YM, TS, AM, SY and TM were involved the collection of the clinical data. HS revised the paper. AK and AT reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (Number 14092958).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brunner C, Lassmann H, Waehneldt TV et al. . Differential ultrastructural localization of myelin basic protein, myelin/oligodendroglial glycoprotein, and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phsphodiesterase in the CNS of adults rats. J Neurochem 1989;52:296–304. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb10930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krupp LB, Tardieu M, Amato MP et al. . International pediatric multiple sclerosis study group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: revisions to the 2007 definitions. Mult Scler 2013;19:1261–7. 10.1177/1352458513484547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huppke P, Rostásy K, Karenfort M et al. . Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis followed by recurrent or monophasic optic neuritis in pediatric patients. Mult Scler 2013;19:941–6. 10.1177/1352458512466317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostásy K, Mader S, Hennes EM et al. . Persisting myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in aquaporin-4 antibody negative pediatric neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler 2013;19:1052–9. 10.1177/1352458512470310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostásy K, Mader S, Schanda K et al. . Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in pediatric patients with optic neuritis. Arch Neurol 2012;69:752–6. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato DK, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto MA et al. . Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2014;82:474–81. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka M, Tanaka K. Anti-MOG antibodies on adult patients with demyelinating disorders of the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol 2014;270:98–9. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kezuka T, Usui Y, Yamakawa N et al. . Relationship between NMO-antibody and Anti-MOG antibody in optic neuritis. J Neuroophthalmol 2012;32:107–10. 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31823c9b6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ et al. . Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006;66:1485–9. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polman C, Reingold S, Banwell B. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Annals Neurol 2011;69:292–302. 10.1002/ana.22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merle H, Olindo S, Bonnan M et al. . Natural history of the visual impairment of relapsing neuromyelitis optica. Ophthalmology 2007;114:810–15. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schluesener HJ, Sobel RA, Linington C et al. . A monoclonal antibody against a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein induces relapses and demyelination in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Immunol 1987;139:4016–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerlero de Rosbo N, Milo R, Lees MB et al. . Reactivity to myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis. Peripheral blood lymphocytes respond predominantly to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Clin Invest 1993;92:2602–8. 10.1172/JCI116875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis—the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med 2006;354.9:942–55. 10.1056/NEJMra052130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]