Abstract

Introduction

Cardiologists face the difficult task of rapidly distinguishing cardiac-related chest pain from other conditions, and to thoroughly consider whether invasive diagnostic procedures or treatments are indicated. The use of cardiac risk-scoring instruments has been recommended in international cardiac guidelines. However, it is unknown to what degree cardiac risk scores and other clinical information influence cardiologists’ decision-making. This paper describes the development of a binary choice experiment using realistic descriptions of clinical cases. The study aims to determine the importance cardiologists put on different types of clinical information, including cardiac risk scores, when deciding on the management of patients with suspected unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Methods and analysis

Cardiologists were asked, in a nationwide survey, to weigh different clinical factors in decision-making regarding patient admission and treatment using realistic descriptions of patients in which specific characteristics are varied in a systematic way (eg, web-based clinical vignettes). These vignettes represent patients with suspected unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Associations between several clinical characteristics, with cardiologists’ management decisions, will be analysed using generalised linear mixed models.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received ethics approval and informed consent will be obtained from all participating cardiologists. The results of the study will provide insight into the relative importance of cardiac risk scores and other clinical information in cardiac decision-making. Further, the results indicate cardiologists’ adherence to the European Society of Cardiology guideline recommendations. In addition, the detailed description of the method of vignette development applied in this study could assist other researchers or clinicians in creating future choice experiments.

Keywords: case scenarios, acute coronary syndromes, risk assesment, decision making

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides insight on how cardiologists weigh clinical information in deciding on the admission and treatment of patients with suspected unstable angina non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

The clinical information presented to cardiologists is varied systematically and presented in clinical vignettes, reflecting clinical practices as closely as possible.

Decision-making is studied in a nationwide survey.

The decision cardiologists were asked to make is a complex decision which (sometimes) has to be made instantly. This was not simulated/taken into account in the clinical vignettes.

The decision had to be made on the basis of seven or eight attributes, while in clinical practice the cardiologists may take into account other aspects in their decision-making.

Introduction

About 6% of the emergency department presentations are due to chest pain.1 Of these patients, a substantial number is diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome, including unstable angina (UA), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST segment myocardial infarction (STEMI).1 2 Mortality after an acute coronary syndrome is substantial.3 4 To prevent cardiac damage or mortality, timely treatment is indicated. As a result, the attending physician has the difficult task to rapidly distinguish cardiac-related chest pain from chest pain caused by other conditions. Patients presenting with chest pain to the emergency department should, therefore, be stratified according to their level of risk of having a cardiac condition.5 Risk assessment is generally based on a patient's clinical history, physical examination, biomarkers and ECG findings.6–9 The decision for hospital admission or type of treatment is dependent on a patients’ risk of adverse cardiac events such as reinfarction or mortality. The European Society of Cardiology guidelines on the management of UA or NSTEMI recommends treatment of patients at high risk of reinfarction or death with invasive procedures or treatment (eg, coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)).7 To determine the patient's risk, several cardiac risk scores have been developed and validated, that is, the HEART,5 GRACE,10 11 TIMI,12 FRISC,13 and PURSUIT score.14 Use of these instruments is recommended by the professional guidelines.7 Despite the availability of valid cardiac risk stratification tools and recommendations for their use in previous studies, low-risk patients were more likely to receive invasive procedures compared with high-risk patients.15–18 Such a treatment risk paradox implies low adherence rates with the guidelines, which possibly affects or even threatens patient safety on the one hand and results in suboptimal resource use on the other hand. Low guideline adherence might be explained by barriers affecting physicians’ attitude towards guideline recommendations,19 including disagreement with the guidelines or unwillingness to adopt the guidelines. In addition, previous research indicates that physicians may consider evidence underlying the guidelines as unconvincing.20 As a result, they may depend heavily on their own personal experience and seem to underestimate important risk factors.21 22 In this study, we focus on cardiologists’ decision-making in the management of UA and NSTEMI. To the best of our knowledge it is unknown to what degree cardiac risk scores and other clinical information influence their decisions about admissions and choice of treatment. The objective of the present study is twofold. First, to determine the influence of a cardiac risk score on cardiologists’ decision on patient admission and treatment. Second, to determine the relative importance of different types of clinical information, in the presence or absence of a risk score, on the management decisions concerning patients with suspected UA or NSTEMI.

Methods and analysis

Study design

To determine how cardiologists weigh different clinical factors (eg, relative importance) in their decision to admit or to treat a patient, binary choice experiments are conducted using vignettes of clinical cases. Two decision moments were investigated, which includes the decision to admit a patient to hospital and the decision to perform cardiac catheterisation. In the vignettes, the clinical factors are systematically varied according to a fractional factorial design.

Study population

Cardiologists working as registered cardiologists in a Dutch hospital will be approached for participation in this study by email. They will be recruited through the Dutch directory of physicians.

Data collection

The data will be collected using a web-based survey, presenting cardiologists with clinical vignettes. The clinical vignettes describe patients by means of a set of attributes, reflecting characteristics of a patient or treatment.23 Clinical vignettes are a frequently applied approach to study decision-making in healthcare as they closely reflect clinical practice.24 In addition, clinical vignettes have been shown to be a valid tool to measure the quality of care.25 26 Cardiologists will be asked to complete a web-based survey containing the clinical vignettes. Prior to completing the survey, cardiologists will be informed about the global study objective and asked to give consent for participation in the study. Cardiologists who initially fail to respond will be sent reminders 1, 3, 8 and 12 weeks after first sending the survey. The completion time of the survey will be approximately 20 min and cardiologists will be able to stop and continue completion of the survey at any time. The data will be processed anonymously.

Survey

The survey registers demographic characteristics, including year of birth, gender, current profession, years of cardiology care experience, whether cardiologists are still actively involved in the care for patients diagnosed with UA or NSTEMI, and which risk score they apply in clinical practice. In addition, associated hospital characteristics such as type of hospital they work in and whether hospitals have revascularisation facilities on site will be registered. After completing the section that registers demographic characteristics, cardiologists are presented with the vignettes. These are presented in two parts that differ in the decision that needs to be made. In the first part of the survey (A), the clinical vignettes describe patients who present themselves with chest pain to the emergency department. Cardiologists are asked to indicate on a binary scale (yes or no) whether he or she would discharge the patient from the emergency department without any further diagnostic testing (eg, no serial troponin testing or exercise testing). In addition, cardiologists are asked on a three-point Likert scale how certain they are of their decision (very sure, sure, somewhat sure). The clinical vignettes in the second part of the study (B) describe a patient's condition when the patient is already admitted to the hospital with a high suspicion of UA or NSTEMI. Cardiologists are asked to indicate whether he or she would advise an invasive procedure, that is, coronary angiography within 72 h from admission and how certain they are of their decision (using the same three-point Likert scale). Cardiologists are asked to make decisions that reflect their actual clinical practice as closely as possible. The survey was pretested among two cardiology residents, not involved in the design of the study, and asked to provide feedback regarding the applicability of the survey. This provided insight on the comprehensiveness of the survey and the time it takes to complete the survey.

Preselection of attributes

Potential attributes relevant for the management of UA and NSTEMI, regarding the decision to admit or treat a patient, were selected from clinical guidelines. It was assumed that these guidelines provided an integral overview of the published scientific evidence and therefore, cover all relevant attributes.6–9 Further, variables of validated risk-scoring instruments,5 10–14 the website ‘up-to-date’,27–29 and recently conducted interviews on the use of risk stratification instruments in practice30 were reviewed for additional relevant attributes. The website ‘up-to-date’ concerns an evidence-based resource that aims to support physicians in clinical decision-making.

Initially, all aspects that can be taken into account when stratifying risk were selected from the aforementioned sources, which resulted in a preselection of 105 potential attributes. As Dutch cardiologists are most familiar with the European Society of Cardiology guidelines in treating their patients, the preselection was subsequently reduced by selecting only those attributes that were mentioned in this guideline and in the validated risk-scoring instruments. This left 56 attributes that were considered of importance for the present study (table 1).

Table 1.

Preselection of attributes (after removal of duplicates)

| Category | Attribute | Source* |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | 1 Older age >75 years | ESC, RS |

| 2 Gender | ESC, RS | |

| Risk factors | 3 Presence of risk factors in general (including positive family history, peripheral artery disease, carotid stenosis, diabetes mellitus, kidney failure, smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, obesity) | ESC, RS |

| 4 Diabetes mellitus | ESC, RS | |

| 5 Chronic kidney failure/creatine level | ESC, RS | |

| 6 Heart failure | ESC, RS | |

| 7 Depressed left ventricular ejection fraction | ESC | |

| 8 Killip class classification | ESC, RS | |

| 9 Anaemia | ESC | |

| 10 Obesity | ESC, RS | |

| 11 Malnutrition | ESC | |

| History | 12 Known coronary artery disease | ESC, RS |

| 13 Previous myocardial infarction | ESC, RS | |

| 14 Previous or recent percutaneous coronary intervention | ESC | |

| 15 Previous or recent coronary artery bypass surgery | ESC | |

| 16 Severity of coronary artery disease | ESC | |

| 17 Cocaine use | ESC | |

| 18 Aspirin use 7 days prior to admission | RS | |

| Clinical presentation | 19 Anamnesis suspicious for cardiac-related chest pain | RS |

| 20 Persistent angina pectoris | ESC, RS | |

| 21 Symptoms of angina pectoris in rest | ESC | |

| 22 Reoccurring angina pectoris | ESC | |

| 23 Several episodes of angina pectoris after event | ESC | |

| 24 Tachycardia | ESC, RS | |

| 25 Hypotensive | ESC, RS | |

| 26 Haemodynamically unstable | ESC | |

| 27 Increased leucocytes at presentation | ESC | |

| 28 Thrombocytopenia at presentation | ESC | |

| 29 Increased bleeding risk | ESC | |

| 30 Presence of bleeding | ESC | |

| 31 Intermediate or high GRACE risk score | ESC | |

| 32 Positive stress test | ESC | |

| 33 Cardiac arrest at admission | ESC, RS | |

| ECG findings | 34 ECG ST segment changes | ESC, RS |

| 35 ECG deviations at rest | ESC | |

| 36 Dynamic ST/T changes | ESC | |

| 37 Negative T waves | ESC | |

| 38 ST depression | ESC | |

| 39 ST elevation | ESC | |

| 40 Ventricular arrhythmia | ESC | |

| Laboratory results | 41 Elevated troponin levels | ESC |

| 42 Elevated biomarkers | ESC, RS | |

| 43 Hyperglycemia | ESC | |

| 44 Elevated C reactive protein | ESC | |

| 45 Elevated B-type natriuretic peptide | ESC | |

| Context information | 46 Revascularization status | ESC |

| 47 Rest ischaemia | ESC | |

| 48 Severity of lesions | ESC | |

| 49 Physical condition of patient | ESC | |

| 50 Fragility of patient | ESC | |

| 51 Cognitive decline | ESC | |

| 52 Functional decline | ESC | |

| 53 Physical dependence | ESC | |

| 54 Quality of life | ESC | |

| 55 Patient's wishes | ESC | |

| 56 Risks versus benefits of revascularization | ESC |

*Attributes are derived from the ESC guideline 2011 and from the GRACE, TIMI, FRISC, PURSUIT and/or HEART risk score.

ESC, European Society of Cardiology; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; RS, risk score.

Final selection of attributes and attribute levels

As it is cognitively difficult for respondents to take into account large numbers of attributes, it is recommended—although there is no standard—to select between 6 and 10 attributes in choice experiments.31–33 This approach was followed in the present study. The final set of attributes was selected by a panel of three cardiologists in collaboration with the research team during a consensus meeting (1 October 2013). These cardiologists were selected based on their affinity with research, and were chosen to reflect diversity in experience and type of hospital they work in. In preparing the consensus meeting, the cardiologists were asked to write down, in order of importance, the six to eight most important attributes when deciding to discharge a patient presenting with acute chest pain from the emergency department without further diagnostic testing (decision moment A). Equally, they listed attributes that were important in deciding on performing a coronary angiography within 72 h for patients with a high suspicion of UA or NSTEMI (decision moment B). In case a cardiologist indicated that an attribute is essential in decision-making, he had the option to select an additional attribute, besides the six to eight that were already selected. The attributes selected by the cardiologists were the starting point for the consensus meeting. The selected attributes were compared and discussed. Furthermore, the cardiologists reviewed and compared the preselection of potential attributes derived from the European Society of Cardiology guidelines and existing risk-scoring instruments. After viewing this list, the cardiologists were given the opportunity to change their own attribute selection for a final selection. None of the cardiologists made any changes in their selection. Again, differences and similarities were discussed until consensus was reached over a final set of eight attributes for decision moment A and seven attributes for decision moment B (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Final selection of attributes and attribute levels of decision moment A

|

Clinical setting: The patient presenting with acute chest pain at the emergency department. Decision: ‘Would you send this patient home without any further diagnostic testing (eg, no serial troponin testing or exercise testing)’? | |

|---|---|

| Attribute | Attribute level |

| Age (years) | <50 |

| 50–75 | |

| >75 | |

| Gender | Male |

| Female | |

| Known coronary artery disease | No |

| Yes | |

| Chest pain classification based on history taking | A-specific chest pain |

| Atypical angina pectoris | |

| Typical angina pectoris | |

| Symptoms of chest pain still present at presentation | No |

| Yes | |

| Risk factors* | No risk factors |

| One risk factor | |

| More than one risk factor | |

| ECG | Normal |

| Atypical changes | |

| Typical ischaemic changes | |

| Troponin† | Below reference level and representative |

| Below reference level, not representative | |

| Above reference level | |

*Classic five: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking and positive family history.

†According to cardiologists’ own hospital standards.

Table 3.

Final selection of attributes and attribute levels of decision moment B

|

Clinical setting: The patient with a suspicion of unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction is admitted for observation in the hospital. Decision: ‘Would you perform a coronary angiography within 72 h in this patient’? | |

|---|---|

| Attribute | Attribute level |

| Age (years) | <70 |

| 70–80 | |

| 80 | |

| Renal function | No renal dysfunction |

| Mild to moderate renal dysfunction | |

| Severe renal dysfunction | |

| Known coronary artery disease | No |

| Yes | |

| Persistent chest pain | No |

| Yes | |

| Risk factors* | No risk factors |

| One risk factor | |

| More than one risk factor | |

| ECG | Normal |

| Atypical changes | |

| Typical ischaemic changes | |

| Troponin† | Normal at repeated measures |

| Significant rise and/or ‘rise and fall’ | |

*Classic five: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking and positive family history.

†According to cardiologists’ own hospital standards.

The arguments whether to select or remove a specific attribute were written down in a logbook. After determining the final set of attributes, the selection and description of attribute levels were discussed and confirmed/approved. In selecting attribute levels, we aimed to select levels that closely reflect the variety of presentations in clinical practice and those that will be easily understood by cardiologists. A secondary goal in selecting attribute levels was to keep the total number of possible vignettes, that is, the full factorial design, as small as possible. Therefore, the number of levels within an attribute was kept to a minimum. The expert panel was reapproached by email to provide a further review of the selected attributes and attribute levels per decision moment on the basis of their initial feedback.

Cardiac risk score

In developing the clinical vignettes, initially cardiac risk score was considered as an attribute. However, this led to unrealistic vignettes and the attribute was, therefore, removed from the full factorial design. Additionally, by using the HEART risk score5 (for decision moment A) and GRACE 2.0 risk score34 (for decision moment B), cardiac risk was estimated for every vignette. This was accomplished by entering the values present in the vignette while holding the remaining parameters constant. The sample of cardiologists will, prior to completion of the survey, be divided in two groups. One group will complete vignettes without a cardiac risk score being present, while the other group completes the vignettes with a cardiac risk score present. Cardiologists will be instructed to consider the risk score which is familiar to their own practice or knowledge.

Selection of clinical vignettes

The attributes and levels for decision moment A comprised 23×35=1944 possible combinations in the full factorial design, where the base of the formula concerns the number of levels of an attribute and the exponent concerns the number of attributes with respectively two or three levels. For decision moment B, 23×34=648 possible vignette combinations could be created. It is practically impossible to present respondents with such a vast amount of vignettes; therefore, a fractional factorial design was created to reduce the number of vignettes for each decision moment. In selecting vignettes, the aim was to estimate the main effects of all attributes. The quality of the selection of vignettes was compared with a theoretical optimum by means of the G efficiency parameter which ranges between 0 (inefficient design) and 1 (efficient design). The G efficiency parameter is a useful guide when judging fractional factorial designs.35 For both decision moments (ie, discharge without further testing and prompt coronary angiography), the number of vignettes were reduced to 64. The vignettes selection showed substantial G efficiency of 0.94 for decision moment A and 0.95 for decision moment B. Per decision moment, the 64 scenarios were randomly allocated into eight blocks containing 8 scenarios each. This is to ensure that all attribute levels will appear with equal frequency in each block.36 Prior to sending the survey, cardiologists will be randomly assigned a block number in SPSS and will be sent the corresponding questionnaire. Each survey comprises 16 scenarios in total (8 per decision moment).

Case description of clinical vignettes

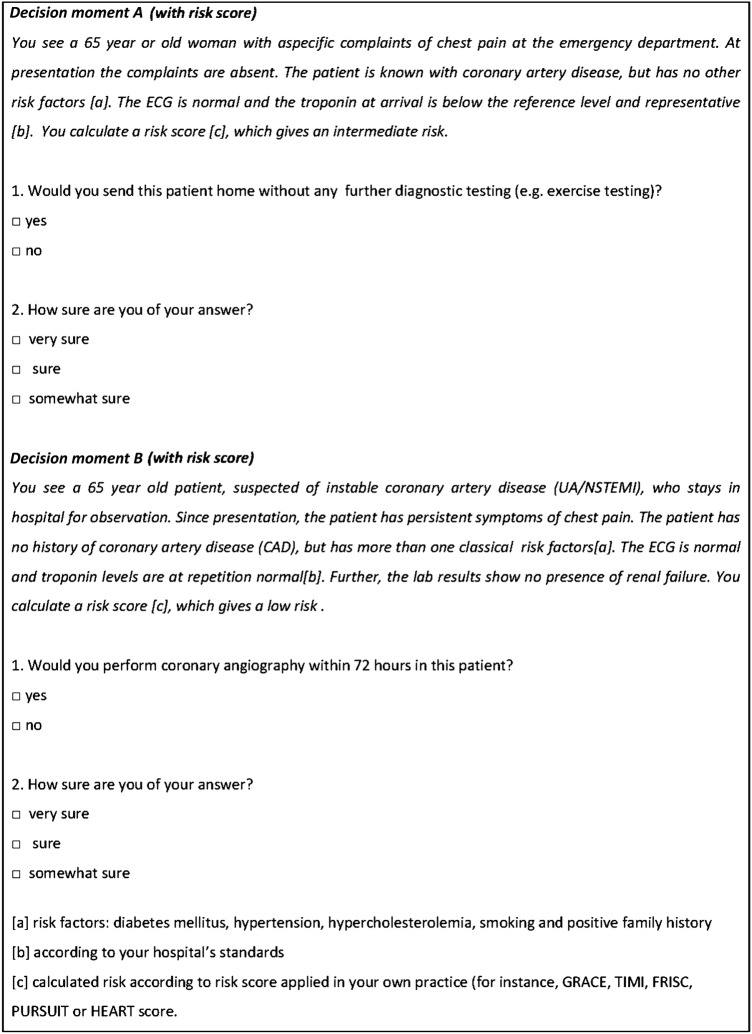

Two members of the research team drafted the initial clinical case descriptions of the vignettes: one representing decision moment A and one representing decision moment B. Next, the clinical case descriptions were discussed and reviewed in a second consensus meeting (26 February 2014), comprising four cardiologists and the research team. This review process was undertaken to ensure accuracy, plausibility and clarity of the clinical event presentation in all of the vignettes. The vignettes were revised until the research team and the panel of cardiologists agreed that the case descriptions represented clinical practice as closely as possible. An example of a vignette is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of clinical vignettes used in the web-based survey (UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction).

Study outcome

The study outcome is the relative importance cardiologists put on different types of clinical information, in the presence and absence of the risk score, when deciding on the management patients of suspected UA or NSTEMI.

Statistical considerations

Demographic characteristics will be presented using descriptive statistics. Associations of independent variables with the binary responses of cardiologists on the clinical vignettes in the survey will be studied with a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM), taking into account random effects for blocks and cardiologists. In total, four models will be created, that is, two for each decision moment taking into account the presence or absence of cardiac risk score information. In the analyses, cardiologists’ responses (yes or no) are the binary outcome measure. Independent variables are the attributes, risk score (if present in the vignette) and the degree of certainty of respondents’ answers. All independent variables will be simultaneously included in the analyses. A significance level of p≤0.05 will be used. The analysis with the GLMM will be performed by Laplacian integration, conducted in R for windows (V.3.0.2) with package lme4.37 The impact of the presence of the risk score on a cardiologist's decision will be studied by comparing results of the analyses with and without presenting risk score information in the vignettes.

Sample size

In total, each cardiologist will complete 16 vignettes (8 for decision moment A and 8 for decision moment B). In calculating the minimum number of cardiologists needed, the following formula is followed: n=500×(c/(a×t)). In this formula, ‘n’ is the minimum number of cardiologists, ‘c’ the largest number of levels for any of the attributes, ‘a’ the number of alternative scenario's that cardiologists are presented with and ‘t’ the total number of choice scenarios per decision moment that each cardiologist is presented with.38 39 In this study, with a minimum sample size of 500×(3/(1×8)), approximately 188 cardiologists are needed per group (with or without a cardiac risk score) to study main effects for decision moments A and B separately. The Dutch directory of physicians contains 963 cardiologists. If a response of 40% is assumed, 385 cardiologists will complete 16 vignettes in total, which will be sufficient for estimating main effects.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the medical ethical committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam (protocol number: 2014008). A waiver of active informed consent was granted, as the study concerns completely anonymised data. A form of informed consent, however, will be conducted at the start of the survey when cardiologists are asked to give consent for their answers to be used and stored for scientific purposes. Results are planned to be disseminated in two papers submitted to peer-reviewed journals and presentations at relevant conferences.

Discussion

UA and NSTEMI are two conditions that are associated with high-mortality rates. Correctly estimating patients’ risk of reinfarction or death, and taking into account this risk in selecting a management strategy is of importance in preventing unnecessary deaths and for optimal use of resources. Cardiac guidelines recommend the use of several sources of information to estimate the risk for an individual patient. However, it is unknown to what degree cardiologists take into account all these aspects in the management of patients with suspected UA or NSTEMI. As mentioned in the introduction, several studies report a treatment risk paradox, that is, low-risk patients were more likely to receive invasive procedures compared with high-risk patients. This implies that cardiac risk scores are not used or not of importance in decision-making regarding admission or invasive treatment. The results of the present study will provide further insight into the complex decision regarding admission and treatment of patients with suspected UA and NSTEMI, and concerns about the degree of adherence to the European Society of Cardiology guideline recommendations. The results of this study could, therefore, be of interest for all practitioners applying these guidelines in the management of patients with suspected UA or NSTEMI. These study outcomes are needed to reduce the variation in practice between cardiologists, hospitals and countries, and as a result find an optimal balance between correctly identifying UA or NSTEMI from the large pool of patients with chest pain presenting at the emergency department, who would benefit most from invasive treatment on the one hand and unnecessary admissions or resource use on the other hand. Also, this study provides other researchers or clinicians aiming to set up a clinical vignette study with a thorough methodological description of all research steps.

Potential limitations

In developing the study, several methodological limitations occurred which potentially affect interpretation of the findings. First, in this study, the outcome measure concerns a complex decision to be made within a limited period of time in a sometimes hectic environment. The vignettes in this study are limited to, respectively, seven and eight attributes for each decision moment, while in clinical practice cardiologists may take into account other aspects in their decision-making, for instance, bleeding risk scores in deciding on coronary angiography. Also cardiologists are not able to see the patient at hand which may influence decision-making. However, clinical vignettes have proven to be a valid and valuable tool to measure the quality of care in previous studies.25 26

Second, the preselection of attributes involved in UA/NSTEMI management were minimised to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines and to variables from existing risk-scoring instruments, as it is cognitively impossible to take into account all attributes. Some attributes are therefore neglected. However, as Dutch cardiologists are most familiar with the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, it was considered reasonable to derive attributes from these guidelines.

Finally, the calculated sample size was based on an assumption that every cardiologist reviews the same vignettes. In the present study, however, every cardiologist reviews the same vignettes, but not all cardiologists will review the same vignettes due to the blocked design. The effect of ignoring this assumption may be limited as it has been previously suggested that a minimum number of six assessments per scenario is sufficient.40 With the present sample size calculation, this requirement is met.

Current status of the study

The survey has been sent out by 4 June 2014. Results are expected by the end of 2014.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the panel of cardiologists—Jeroen Bunge (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands), Dr Maarten-Jan Cramer (UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), Wouter Tietge (Diaconessenhuis, Leiden, The Netherlands) and Ruben Uijlings (Deventer ziekenhuis, Deventer, The Netherlands)—for their assistance in developing the clinical vignettes.

Footnotes

Contributors: JE and IvdW designed the study. JMP, JBR, MCdB and CW provided intellectual input into conception and design of the study. IvdW designed the clinical vignettes (eg, construction of the fractional factorial and block design). JE drafted the manuscript, and prepared the manuscript for publication. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Medical ethical committee of VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J et al. . The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart 2005;91:229–30. 10.1136/hrt.2003.027599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee TH, Goldman L. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1187–95. 10.1056/NEJM200004203421607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen LA, O'Donnell CJ, Camargo CAJ et al. . Comparison of long-term mortality across the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2006;151:1065–71. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J 2008;16:191–6. 10.1007/BF03086144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM et al. . ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation 2007;116:e148–304. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S et al. . ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aroney CN, Aylward P, Kelly A et al. . Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2006. Med J Aust 2006;184:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Unstable angina and NSTEMI. The early management of unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clinical guideline 94 2010.

- 10.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O et al. . Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2345–53. 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox KAA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ et al. . Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ 2006;333:1091 10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ et al. . The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA 2000;284:835–42. 10.1001/jama.284.7.835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagerqvist B, Diderholm E, Lindahl B et al. . FRISC score for selection of patients for an early invasive treatment strategy in unstable coronary artery disease. Heart 2005;91:1047–52. 10.1136/hrt.2003.031369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boersma E, Pieper KS, Steyerberg EW et al. . Predictors of outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation. Results from an international trial of 9461 patients. The PURSUIT Investigators. Circulation 2000;101:2557–67. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.22.2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M et al. . In-hospital revascularization and one-year outcome of acute coronary syndrome patients stratified by the GRACE risk score. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:913–16. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M et al. . Management patterns in relation to risk stratification among patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1009–16. 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roe MT, Peterson ED, Newby LK et al. . The influence of risk status on guideline adherence for patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2006;151:1205–13. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox KAA, Anderson FAJ, Dabbous OH et al. . Intervention in acute coronary syndromes: do patients undergo intervention on the basis of their risk characteristics? The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Heart 2007;93:177–82. 10.1136/hrt.2005.084830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR et al. . Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65. 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manfrini O, Bugiardini R. Barriers to clinical risk scores adoption. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1045–6. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CH, Tan M, Yan AT et al. . Use of cardiac catheterization for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes according to initial risk: reasons why physicians choose not to refer their patients. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:291–6. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan AT, Yan RT, Huynh T et al. . Understanding physicians’ risk stratification of acute coronary syndromes: insights from the Canadian ACS 2 Registry. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:372–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson RT, Louviere JJ. A common nomenclature for stated preference elicitation approaches. Environ Resour Econ 2011;49:539–59. 10.1007/s10640-010-9450-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachmann LM, Muhleisen A, Bock A et al. . Vignette studies of medical choice and judgement to study caregivers’ medical decision behaviour: systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:50 10.1186/1471-2288-8-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P et al. . Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000;283:1715–22. 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P et al. . Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:771–80. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Up-to-date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-acute-managementof-unstable-angina-and-non-st-elevation-myocardial-infarction?source=see_link (accessed Jun 2013).

- 28.Up-to-date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/risk-factors-for-adverse-outcomes-after-non-st-elevation-acute-coronary syndromes?source=search_result&search=acute +coronary+syndrome+risk+factors&selectedTitle=5%7E150 (accessed Jun 2013).

- 29.Up-to-date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-risk-equivalentsand-established-risk-factors-forcardiovasculardisease?source=search_result&search=acute +coronary+syndrome+risk+factors&selectedTitle=1%7E150 (accessed Jun 2013).

- 30.Engel J, Heeren M, van der Wulp I et al. . Understanding factors that influence the use of cardiac risk scores in daily practice: a qualitative study of health care providers’ perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:418 10.1186/1472-6963-14-418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003;2:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeShazo JR, Fermo G. Designing choice sets for stated preference methods: the effects of complexity on choice consistency. J Environ Econ Manag 2002;44:123–43. 10.1006/jeem.2001.1199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do)… designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:151–8. 10.1093/heapol/czn047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox KAA, FitzGerald G, Puymirat E et al. . Should patients with acute coronary disease be stratified for management according to their risk? Derivation, external validation and outcomes using the updated GRACE risk score. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004425 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheeler RE. Comments on algorithmic design 2004–2009. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/AlgDesign/vignettes/AlgDesign.pdf (accessed Jan 2014).

- 36.Hall J, Kenny P, King M et al. . Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to evaluate the introduction of varicella vaccination. Health Econ 2002;11:457–65. 10.1002/hec.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orme B. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Madison: Research Publishers LLC, 2010:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose JM, Bliemer MCJ. Sample size requirements for stated choice experiments. Transportation 2013;40:1021–41.

- 40.Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods. Analysis and application. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000:83–111. [Google Scholar]