Abstract

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous hereditary auditory pigmentary disorder characterized by congenital sensorineural hearing loss and iris discoloration. Many genes have been linked to WS, including PAX3, MITF, SNAI2, EDNRB, EDN3, and SOX10, and many additional genes have been associated with disorders with phenotypic overlap with WS. To screen all possible genes associated with WS and congenital deafness simultaneously, we performed diagnostic exome sequencing (DES) in a male patient with clinical features consistent with WS. Using DES, we identified a novel missense variant (c.220C>G; p.Arg74Gly) in exon 2 of the PAX3 gene in the patient. Further analysis by Sanger sequencing of the patient and his parents revealed a de novo occurrence of the variant. Our findings show that DES can be a useful tool for the identification of pathogenic gene variants in WS patients and for differentiation between WS and similar disorders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of genetically confirmed WS in Korea.

Keywords: Exome, PAX3, Waardenburg syndrome

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by congenital sensorineural hearing loss and pigmentary disturbances of the iris, hair, and skin, with or without dystopia canthorum [1]. Its prevalence is estimated to be 1/42,000, and it is responsible for 1-3% of all congenital deafness cases [2].

Four subtypes of WS have been described thus far. WS type I (WS1; MIM 193500) includes dystopia canthorum (an outward displacement of the inner canthi), and this feature distinguishes WS1 from WS type II (WS2; MIM numbers 193510, 600193, 606662, 608890, and 611584 for 2A to 2E) [3]. WS type III (WS3; MIM 148820) is similar to WS1 but includes musculoskeletal anomalies of the upper limbs. WS type IV (WS4; MIM numbers 277580, 613265, and 613266 for 4A to 4C) is similar to type I but has features of Hirschsprung disease [4]. Despite many efforts to clinically differentiate between the subtypes of WS by diagnostic criteria [5], the rarity and highly varied expression has limited the ability to make an accurate diagnosis in individual patients. In addition, hearing loss and early graying are relatively common in the general population and are not specific to WS [6]. Thus, the accuracy of WS diagnosis needs to be improved by the use of additional diagnostic procedures.

In addition to the variable phenotypic expressivity of WS, the genetic heterogeneity also creates significant challenges for both clinical diagnosis and genetic counseling. Many causative genes have been identified for WS and are the basis of disease classification as follows: WS1 (causative gene: PAX3), WS2 (MITF, SNAI2, and SOX10), WS3 (PAX3), and WS4 (EDNRB, EDN3, and SOX10) [1]. Furthermore, many genes are associated with deafness and hearing loss that should be differentiated, such as DIAPH1, KCNQ4, GJB3, GJB2, GJB6, MYH14, DFNA5, WFS1, TECTA, and COCH[6].

Recently, diagnostic exome sequencing (DES) has been introduced to analyze the exons and flanking intronic regions of these genes with clinical relevance. DES is appropriate for a variety of exome sequencing indications providing lower turnaround times, lower cost, more comprehensive coverage of target regions without the complexity of whole exome analysis. Given that there are potentially many genes associated with WS and that similar clinical phenotypes may be problematic for diagnosis, we performed DES to identify a pathogenic variant in a Korean patient suspected of having WS.

A 27-yr-old man with bilateral hearing impairment presented to our hospital for genetic diagnosis. His prenatal history was unremarkable, and no pregnancy concerns were reported. He had heterochromia of the right iris, but dystopia canthorum was uncertain. No relevant family history was documented. The clinical features of the patient suggested WS; however, other WS-like disorders associated with congenital deafness could not be excluded. As conventional gene-by-gene sequencing is too costly and time-consuming, DES, which allows simultaneous analysis of multiple clinically relevant genes, was performed with the written informed consent of the patient.

Genomic DNA was enriched by using the TruSight One Sequencing Panel (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA), which includes 125,395 probes targeting a 12-Mb region spanning 4,813 genes, and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Raw sequence reads were processed and aligned to the hg19 human reference sequence with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, version 0.7.5). Duplicate reads were removed with Picard and local alignment optimization was performed with the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK, version 3.1.1). The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and short indel candidates were identified and these variants were annotated by ANNOVAR to filter SNPs reported in the SNP database (dbSNP, build 129) and the 1000 Genomes Project (http://1000genomes.org). The Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) and Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) algorithms were used to predict the effects of the missense variants on protein function. Nucleotide conservation between mammalian species was evaluated by using the Evolutionary Annotation Database (Evola version 7.5, http://www.h-invitational.jp/evola/). The candidate variant identified by DES was confirmed by using conventional Sanger sequencing.

A mean coverage of 105.49× was achieved, and 95.21% of targeted bases were read >20 times by exome capture and sequencing. A total of 92,759 SNPs were identified, and the pathogenic variant was prioritized by using the following steps. After exclusion of nongenic intronic variants and synonymous exonic variants, 3,722 variants remained. Among these, common polymorphisms listed in dbSNP129 with a minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05 were excluded. After screening of all WS-related genes and congenital deafness, we found a novel missense variant (c.220C>G; p.Arg74Gly) in the PAX3 gene.

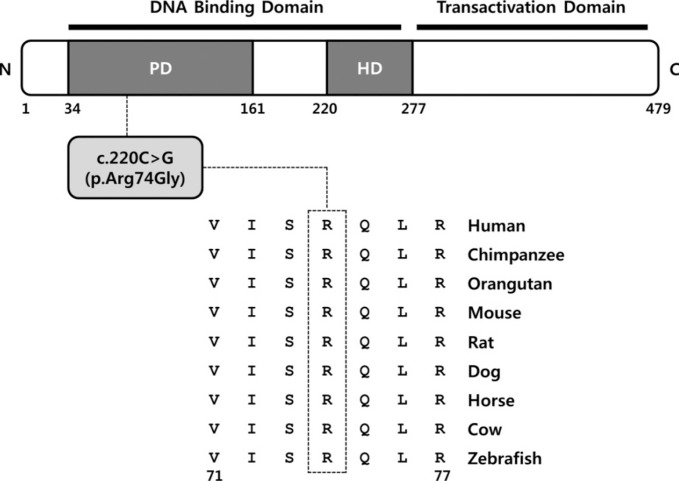

The p.Arg74Gly variant was likely pathogenic because the affected residue is strictly conserved from zebrafish to human (Fig. 1), and the variant was predicted to be deleterious by in silico analysis by using SIFT and PolyPhen-2. The p.Arg74Gly variant was absent in the dbSNP and was not found in 11,906 chromosomes in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Exome Sequencing Project database. In addition, the variant was not observed in in-house control exomes of individuals of Korean descent. We regarded this variant as the best candidate and subsequently validated it by Sanger sequencing.

Fig. 1. Ortholog conservation of a novel PAX3 variant. Schematic representation of the PAX3 variant relative to the protein domain. Protein sequence alignment of PAX3 in vertebrate species. The region of alignment corresponding to the missense variant is shown. Arg (R) at codon 74 is highly conserved across all species (indicated by the open box). The Ensembl IDs for the aligned PAX3 amino acid sequences are as follows: human, ENSP 00000343052; chimpanzee, ENSPTRT00000024032; orangutan, ENSPPYT00000015369; mouse, ENSMUSP00000004994; rat, ENSRNOT00000018652; dog, ENSCAFT00000025445; horse, ENSECAT00000015993; cow, ENSBTAT00000013131; and zebrafish, ENSDART00000014350.

Abbreviations: PD, paired domain; HD, homeodomain.

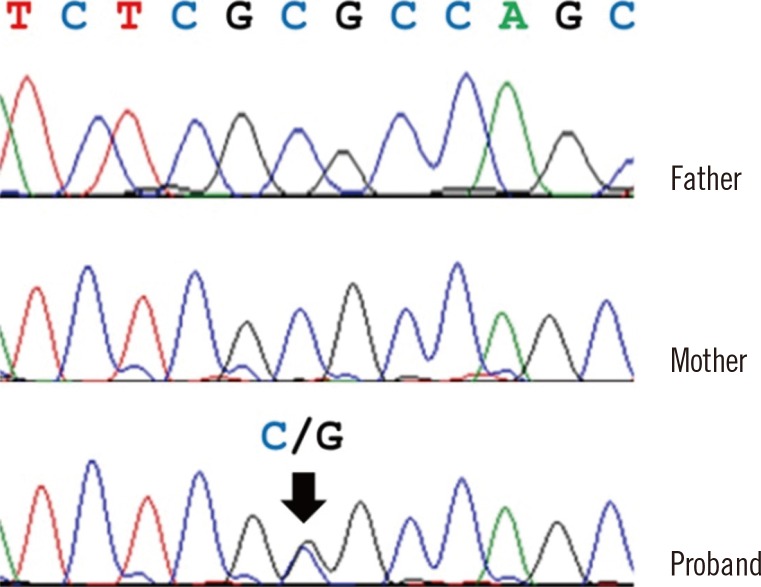

The PAX3 variant was validated by Sanger sequencing in the patient and his parents. We confirmed the heterozygous PAX3 variant (NM_181457.3:c.220C>G, p.Arg74Gly) was present in the patient; however, his parents did not have the variant, indicating that it occurred de novo (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Validation of a novel PAX3 variant by Sanger sequencing. The patient had a nonsynonymous substitution (c.220C>G; p.Arg74Gly, arrow) in PAX3. The patient's father and mother did not have this variant.

In this report, we present a patient carrying a de novo novel variant in the PAX3 gene successfully identified through DES. Although several Korean cases with WS have been reported [710], no molecular confirmation has been performed in such cases to date.

Patients with rare diseases often undergo a lengthy, time-consuming process for a definitive diagnosis, commonly referred to as a "diagnostic odyssey." This is due to clinical and genetic heterogeneity of the hereditary condition, unusual presentation, and lack of specific clinical-genetic knowledge of the attending physicians [11]. The use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies to examine multi-gene targeted panels might be useful for diseases with genetic heterogeneity. If NGS is performed early on, patients may escape the tedious, expensive, and emotionally wrenching "diagnostic odyssey" [12].

There are many multi-gene targeted panels for single diseases such as cancer, cardiac disease, immune disorders, and neurological disorders. The TruSight One Sequencing Panel provides the largest coverage of 4,813 clinically relevant genes available, which are selected on the basis of information in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), and other commercially available sequencing panels. Laboratories can analyze all of the genes on the panel or focus on a specific subset. As in the present case, this new diagnostic sequencing significantly shortens the diagnostic process, especially in conditions that have phenotypic overlap with a variety of single-gene disorders.

The PAX3 gene is located on chromosome 2q36.1 and encodes a DNA-binding transcription factor expressed in neural crest cells [13]. It plays an important role in the development and differentiation of melanocytes, which originate from the embryonic neural crest [13]. The PAX3 protein contains two highly conserved DNA binding domains, a paired domain and a homeodomain corresponding to exons 2-6 of the PAX3 gene. To date, more than 100 PAX3 pathogenic variants have been reported to be associated with WS (HGMD professional version for release 2014.2). Approximately 95% of the PAX3 pathogenic variants are located in DNA binding domains, and the highest proportion of pathogenic variants is found in exon 2 of the paired domain [1]. Matsunaga et al. [14] reported that the p.Ile59Phe pathogenic variant, which is located in the paired domain, is likely to distort the structure of the DNA-binding site of PAX3 and lead to functional impairment. The novel pathogenic variant found in this study is predicted to alter the highly conserved arginine at codon 74, which plays a role in paired domain DNA binding; therefore, it may influence DNA-binding activity and transactivation capabilities resulting in a disease phenotype. Further functional study is needed to confirm its causal mechanism.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first molecular genetic analysis of a WS1 patient from the Korean population. We identified a novel missense pathogenic variant (c.220C>G; p.Arg47Gly) in the PAX3 gene. This report will contribute to a better understanding of the genetic background in Korean WS patients. We also showed that DES can be a useful tool to identify causative pathogenic variants in patients with WS.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Pingault V, Ente D, Dastot-Le Moal F, Goossens M, Marlin S, Bondurand N. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:391–406. doi: 10.1002/humu.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read AP, Newton VE. Waardenburg syndrome. J Med Genet. 1997;34:656–665. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.8.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardono E, van Bever Y, van den Ende J, Havrenne PC, Iughetti P, Maestrelli SR, et al. Waardenburg syndrome: clinical differentiation between types I and II. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;117A:223–235. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wildhardt G, Zirn B, Graul-Neumann LM, Wechtenbruch J, Suckfüll M, Buske A, et al. Spectrum of novel mutations found in Waardenburg syndrome types 1 and 2: implications for molecular genetic diagnostics. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001917. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrer LA, Grundfast KM, Amos J, Arnos KS, Asher JH Jr, Beighton P, et al. Waardenburg syndrome (WS) type I is caused by defects at multiple loci, one of which is near ALPP on chromosome 2: first report of the WS consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:902–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouyang XM, Yan D, Yuan HJ, Pu D, Du LL, Han DY, et al. The genetic bases for non-syndromic hearing loss among Chinese. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:131–140. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JH, Moon SK, Lee KH, Lew HM, Chang YH. Three Cases of Waardenburg syndrome type 2 in a Korean family. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2004;18:185–189. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2004.18.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kee SY, Lee YC, Lee SY. Type 3 Waardenburg syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;46:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SC. A case of Waardenburg syndrome type 2 with anisocoria. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010;51:1423–1426. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shim HC, Kim JK, Park DJ. A case of Waardenburg syndrome type 4. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013;54:176–179. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohmann K, Klein C. Next generation sequencing and the future of genetic diagnosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0288-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez CM, Das S. Clinical exome sequencing: the new standard in genetic diagnosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1215–1216. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strachan T, Read AP. PAX genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:427–438. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsunaga T, Mutai H, Namba K, Morita N, Masuda S. Genetic analysis of PAX3 for diagnosis of Waardenburg syndrome type I. Acta Otolaryngol. 2013;133:345–351. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.744470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]