Abstract

Introduction

Australian and international clinical practice guidelines are available for common paediatric conditions. Yet there is evidence that there are substantial variations between the guidelines, recommendations (appropriate care) and the care delivered. This paper describes a study protocol to determine the appropriateness of the healthcare delivered to Australian children for 16 common paediatric conditions in acute and primary healthcare settings.

Methods and analysis

A random sample of 6000–8000 medical records representing a cross-section of the Australian paediatric population will be reviewed for appropriateness of care against a set of indicators within three Australian states (New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia) using multistage, stratified sampling. Medical records of children aged <16 years who presented with at least one of the study conditions during 2012 and 2013 will be reviewed.

Ethics and dissemination

Human Research Ethics Committee approvals have been received from the Sydney Children's Hospital Network, Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service and Women's and Children's Hospital Network (South Australia). An application is under review for the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. The authors will submit the results of the study to relevant journals and offer oral presentations to researchers, clinicians and policymakers at national and international conferences.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Obtain population-level information regarding the appropriateness of healthcare delivered for Australian children for a range of conditions.

Provide baseline condition and indicator data for ongoing monitoring in Australia overall, state and regional areas.

The potential attrition rate of healthcare practices may introduce selection bias.

Introduction

Widespread variation in the healthcare delivered to patients persists despite the availability of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the past 20 years.1 CPGs emerged to promote the uptake of evidence into routine practice and standardise care. However healthcare professionals do not always follow them.2–7 Further, there are many examples of variation in healthcare delivery which can impact on health outcomes as well as generate financial waste.8 9 For example, childhood asthma is estimated to affect more than 10% of Australian children and, over a 12 month period, be associated with 15% of children missing school and 4% of all hospital admissions.10 However, inappropriate prescribing of combination pharmaceuticals containing inhaled steroids and long-acting β-agonists for asthma can lead to unnecessary costs for consumers and the healthcare system resulting in adverse events and contributing to poor asthma control.11 12

The measurement of how often appropriate care is delivered (care in line with evidence-based or consensus-based guidelines) can identify variations and gaps in care. Our adult study, CareTrack Australia (CTA),3 13 14 undertaken by a number of the current authors, demonstrated that there are large gaps in the provision of appropriate care to patients, which is delivered on average only 57% of the time.14 There is also considerable variation by type of healthcare practice (HCP; range 32–80%) and condition (13–90%).14 These results are similar to the only other system-wide study of appropriateness of healthcare which showed that adults in the USA received ‘recommended care’ only 55% of the time.15 In paediatrics there is only one comprehensive international study. This examined care in the USA during 1998 and 2000 and was published in 2007.16 This showed that children received appropriate care 68% of the time for acute medical problems, 53% for chronic medical conditions and 41% for preventive healthcare, yielding an average of 47%.16 Clearly there is a need for strategies to reduce such deficits in order to deliver appropriate healthcare more effectively and efficiently.14–16 Information at a population level regarding the appropriateness of healthcare delivered for children for a range of conditions is not available in Australia.

CareTrack Kids (CTK) aims to measure the appropriateness and safety of the healthcare delivered to children in Australia, and to establish a baseline for the variation and gaps in care identified. The CTK project involves a suite of three related studies: part 1—developing a set of clinical ‘appropriateness’ indicators for common paediatric conditions;17 part 2—this study—measuring the appropriateness of paediatric care in Australia against these clinical indicators (using an on-site retrospective review of medical records during 2012 and 2013) and part 3 collecting information regarding the prevalence and characteristics of adverse events in paediatric healthcare encounters during 2012 and 2013.18

This protocol paper describes the methodology for part 2 of the CTK project. The primary aim is to measure the appropriateness of healthcare delivered to Australian children for 16 common conditions during 2012 and 2013 in acute, primary, community and hospital healthcare settings. The study will identify areas with poor compliance for selected conditions to enable targeted healthcare improvements and provide baseline condition and indicator data for the ongoing monitoring of care for these conditions in Australia and at national, state, district/network and facility levels (box 1).

Box 1. Definitions used13.

Condition refers to acute (eg, abdominal pain, gastroenteritis) and chronic (eg, asthma, diabetes) conditions or being eligible for screening or preventive care (eg, immunisations)

Evidence-based care (EBC) is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of EBC means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research

Appropriate care for this study is clinical care for a condition considered to be evidence based or consensus based by a panel of clinical experts in Australia in the context in which it was delivered in the years 2012 and 2013

Indicator is a condition-specific process measurement of healthcare management, appropriate for Australian practice during 2012 and 2013. Each indicator is scored as to whether eligible processes for prevention (eg, immunisation), monitoring (eg, asthma inhaler technique, glycated haemoglobin annual check) or treatment (eg, antibiotics, prednisolone) have been carried out by answering ‘yes’ or ‘no’

Healthcare provider refers to doctors, nurses, medical specialists and clinical psychologists

Healthcare practices (HCP) refers to hospitals, general practices, facilities, clinics, community centres

Encounter means any consultation with a healthcare provider or attendance at a HCP for an activity relevant to one of the selected conditions for which there is an eligible indicator

Compliance with indicators is expressed as the percentage of eligible healthcare encounters at which appropriate care was received. Eligibility or scoring will be determined by the criteria listed under component 9 of the Methods section

Surveyor is a person with appropriate clinical and audit experience who has been trained and accredited for this study to review medical records in relation to the care indicators

Methods and analysis

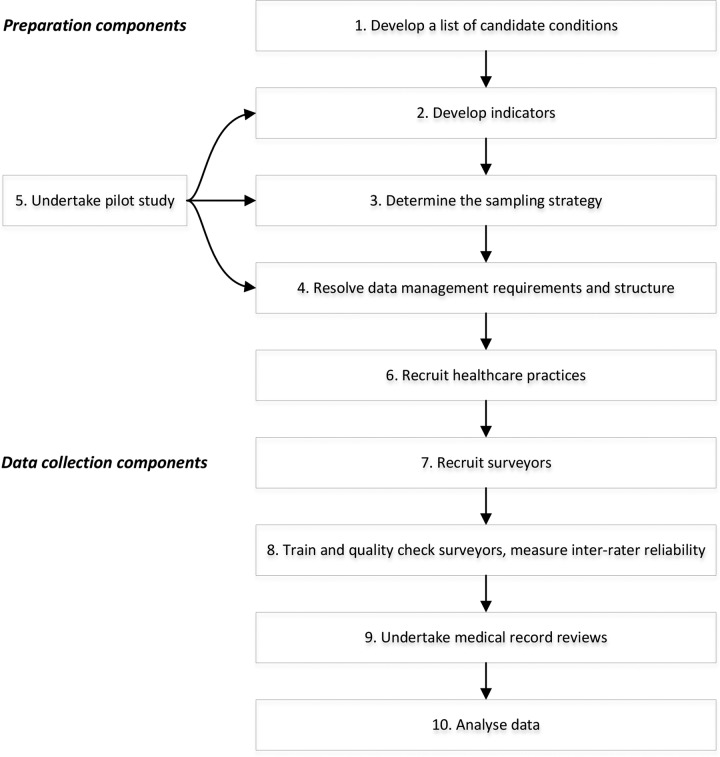

This protocol is based on the methods used in the USA16 and CTA14 studies. We will develop a set of indicators for common paediatric conditions, recruit HCPs, and collect information on-site from the HCP medical records. Medical records will be reviewed of children aged <16 years who presented with at least one of the 16 study conditions during 2012 and 2013. Our study will be a retrospective review of medical records, assessed against indicators of appropriate care. There are 10 components to this protocol (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Components of the CareTrack Kids study.

Component 1: develop a list of candidate conditions

We identified 20 conditions amenable to population-level appropriateness of care research, based in published research,19 20 burden of disease21 and quality of care priority lists.21 We also included other high prevalence conditions which are not well captured by these data sources (eg, obesity22 and urinary tract infection).23 Following the pilot study (component 5) the CTK research team will assess each condition for feasibility (level of documentation in the medical record AND/OR the indicator is applicable to sufficient patients), impact (effect on patient health outcomes and/or healthcare system costs) and prevalence in order to confirm the final list of 16 conditions.

Component 2: develop indicators

Candidate indicators will be extracted from national and international CPGs. These will be collated, reviewed internally by CTK research team, and then posted on a wiki site for open, transparent review of their feasibility, acceptability and clinical impact by national clinical experts. This process has been described in detail elsewhere.17

Component 3: determine the sampling strategy

Sampling method

A multistage, randomised, stratified sampling plan will be used to obtain a representative, national estimate of the percentage of healthcare encounters at which Australian children receive appropriate care. This sampling plan describes: the total number of medical records to be reviewed, the allocation of condition sampling per HCP type, the selection of geographical areas per state, the desired number and type of hospitals, the number and type of HCPs and the number of medical records per HCP. Geographical areas within the three states are defined by South Australian (SA) Local Health Networks, New South Wales (NSW) Local Health Districts and Queensland (QLD) Hospital and Health Services. The sampling plan will first select geographical areas within participating states, then HCPs within geographical areas after stratifying by metropolitan and regional locations. Medical records will be selected for review by sampling the databases of these nominated HCPs. Estimates of compliance with indicator at condition, state and national level and stage of care (screening, diagnosis, treatment, ongoing management) will also be reported (secondary outcomes).

Number of medical records to be reviewed per condition

Assuming a 95% CI and an infinite population, at least 384 medical record reviews (MRRs) are required to estimate the true proportion of medical records that document appropriate care for 5% precision, and 97 records for 10% precision.24 A conservative prevalence estimate of 50% was used in these sample size calculations, since a priori data do not exist for appropriate care delivered in Australian children as a national estimate. These calculations were determined at medical record level, since HCP encounters are nested within medical records and are challenging to compile into a sampling frame.

A minimum of 400 records per condition will be reviewed to report national estimates at condition level with 5% precision. A minimum of 100 records per condition will be reviewed in each state for state-based reporting at 10% precision, and with allocation to metropolitan and regional locations according to population size. This study will not be powered for indicator reporting by stage of care.

Based on this, 100 MRR per condition will be allocated to SA and 300 MRR per condition to each of NSW and QLD (approximately proportional to the size of the state and location; table 1). With 16 conditions being assessed, at least 6400 records will be reviewed to achieve the primary study aim—a national estimate with precision under 5%.

Table 1.

Allocation of sample to the participating states per condition and stratified by geographical location

| State | Geographical location | Population count (0–16 years)* | Proportion (%) | Number of medical record reviews25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | State | – | – | 183† |

| Metropolitan | 1 098 745 | 39.6 | 134 | |

| Regional | 401 868 | 15.4 | 49 | |

| QLD | State | – | – | 118† |

| Metropolitan | 593 910 | 21.4 | 73 | |

| Regional | 366 202 | 13.2 | 45 | |

| SA | State | – | – | 100† |

| Metropolitan | 232 974 | 8.4 | 74 | |

| Regional | 81 719 | 2.9 | 26 |

*Population counts according to the 2011 Population Census.25

†Allocate 100 to SA and 300 to QLD and NSW proportionally (based on size of the state and geographical area).

NSW, New South Wales; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia.

There will be a design effect, since records will be clustered by HCP facilities, and non-responses. A pilot study (component 5) will be used to obtain an estimate of the proportion of appropriate care delivered for some conditions, HCP response rates and the intraclass correlation by HCP type. Sample size estimates will be adjusted as necessary based on the results of the pilot study. It is expected that between 6000 and 8000 records will be reviewed.

Condition sampling

Each condition can be managed by more than one HCP type. Since CTK will recruit HCPs and sample from their databases, the proportion of management by each HCP for each condition needs to be specified. All available prevalence data (with gaps for some conditions) and input from expert clinicians were used to estimate the proportion of frequency of attendance by HCP type for each condition (table 2). All percentages were rounded to the nearest multiple of five, to highlight that these are approximate. Preventive care is not a standard condition and the data collected for this condition will be opportunistic (and hence not included in the sample size calculation). All hospital, emergency department (ED) and general practice (GP) records reviewed for the other conditions will also be assessed for preventive care.

Table 2.

Proposed frequency of attendance to HCP types and condition

| Weighting by HCP type (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Hospital | Emergency department | General practice | Specialist | Clinical psychologists | |

| 1 | Abdominal pain | 5 | 50 | 45 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | ADHD | 0 | 0 | 20 | 50 | 50 |

| 3 | AGE | 5 | 10 | 85 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Anxiety/depression | 5 | 5 | 40 | 30 | 20 |

| 5 | Asthma | 5 | 10 | 80 | 5 | 0 |

| 6 | Autism | 0 | 0 | 20 | 50 | 30 |

| 7 | Bronchiolitis, acute | 10 | 10 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | Croup | 5 | 25 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Diabetes | 20 | 35 | 10 | 35 | 0 |

| 10 | Eczema | 5 | 5 | 75 | 15 | 0 |

| 11 | Fever, unspecified | 5 | 60 | 30 | 5 | 0 |

| 12 | GORD | 20 | 5 | 65 | 10 | 0 |

| 13 | Head injury | 5 | 70 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Obesity | 5 | 0 | 85 | 10 | 0 |

| 15 | Otitis media | 0 | 10 | 80 | 10 | 0 |

| 16 | Status epilepticus | 15 | 55 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

| 17 | Tonsillitis | 10 | 10 | 75 | 5 | 0 |

| 18 | UTI | 5 | 15 | 75 | 5 | 0 |

| 19 | URTI | 5 | 15 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Preventive care | all | all | all | 0 | 0 |

All percentages have been rounded to the nearest multiple of 5.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AGE, acute gastroenteritis; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; HCP, healthcare practice; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

The allocations in table 2 reflect estimated frequency of attendance but not the amount of time spent on care or severity of conditions. In order to obtain sufficient records across HCP types when stratified by geographical location and state, we will oversample some HCP types and undersample others. At the end of the study, sample weights according to table 2 will be applied when analysing the data (component 10).

Regional sampling

The Australian states of NSW, QLD and SA account for 51% of the Australian population of children under 14 years of age25 and were selected based on relationships with CTK partners. In each of these States all hospitals dedicated to the care of children will be included. Geographical areas will be eligible for inclusion if there is at least one non-children's hospital receiving at least 2000 ED presentations and at least 500 paediatric inpatient admissions per annum. A sampling frame of geographical areas will be constructed stratified by state and location (metropolitan, regional). In total, 11 geographical areas will be involved in this study as listed in table 3 (two metropolitan and two regional per state). SA had only three eligible areas (two metropolitan and one regional), so all were selected. Within the remaining four stratum per state (NSW and QLD), two areas each were selected for each location using SAS V.9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to perform the randomisation. The same number of records will be reviewed in each of the metropolitan and regional areas selected within a stratum.

Table 3.

NSW and QLD stratum

| State | Geographical location | Geographical area name* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NSW | Metropolitan | Central Coast |

| 2 | NSW | Metropolitan | Illawarra Shoalhaven |

| 3 | NSW | Metropolitan | Nepean Blue Mountains |

| 4 | NSW | Metropolitan | Northern Sydney |

| 5 | NSW | Metropolitan | South Eastern Sydney |

| 6 | NSW | Metropolitan | South Western Sydney |

| 7 | NSW | Metropolitan | Western Sydney |

| 1 | NSW | Regional | Hunter New England |

| 2 | NSW | Regional | Mid North Coast |

| 3 | NSW | Regional | Murrumbidgee |

| 4 | NSW | Regional | Northern NSW |

| 5 | NSW | Regional | Western NSW |

| 1 | QLD | Metropolitan | Gold Coast |

| 2 | QLD | Metropolitan | Metro North |

| 3 | QLD | Metropolitan | Metro South |

| 4 | QLD | Metropolitan | West Moreton |

| 1 | QLD | Regional | Cairns and Hinterland |

| 2 | QLD | Regional | Central Queensland |

| 3 | QLD | Regional | Darling Downs |

| 4 | QLD | Regional | Mackay |

| 5 | QLD | Regional | Sunshine Coast |

| 6 | QLD | Regional | Townsville |

| 7 | QLD | Regional | Wide Bay |

*Only eligible geographical areas are included.

NSW, New South Wales; QLD, Queensland.

HCP sampling

The hospitals in table 4 will be invited to participate: all six major/tertiary children’s hospitals in NSW, QLD and SA; and hospitals within each of the areas that provide substantive (as defined previously) emergency and inpatient services. Once the sampling frame containing all the GPs, specialists, paediatricians and clinical psychologists who are geographically located within the selected state areas has been compiled a simple random sample of practices will be selected using a SAS randomisation script. An invitation to participate will be sent to the practices selected, if a practice declines the next practice on the list will be approached. Across all conditions and areas combined, a total of 555 HCPs are required. The number needed to recruit by HCP type across all conditions and areas is: hospitals n-23, ED n-23, GPs n-155, specialists n-258 and clinical psychologists n-96.

Table 4.

Hospitals selected for invitation to participate in CTK

| State | Areas | Hospitals |

|---|---|---|

| NSW | Sydney Children's Hospitals Network | Sydney Children's Hospital* Children's Hospital at Westmead* |

| Hunter New England Network | John Hunter Children's* | |

| Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District | Wollongong | |

| South Western Sydney Local Health District | Bankstown Bowral Campbelltown Fairfield Liverpool |

|

| Northern NSW Local Health District | Grafton Lismore The Tweed |

|

| Western NSW Local Health District | Bathurst Dubbo Orange |

|

| QLD | Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service | Royal Children's* Mater Misericordiae* |

| Gold Coast Health Service District | Gold Coast University Robina |

|

| Metro North Health Service District | Caboolture The Prince Charles Redcliff |

|

| Central QLD Health Service District | Gladstone Rockhampton |

|

| Wide Bay Health Service District | Bundaberg Hervey Bay Maryborough |

|

| SA | Women's and Children's Health Network | Women's and Children's* |

| Southern Adelaide Local Health Network | Flinders Medical Centre Noarlunga Health Service | |

| Northern Adelaide Local Health Network | Lyell McEwin Modbury |

|

| Country Health SA Local Health Network (SA Regional) | Whyalla Port Augusta Mt Gambier |

*Major/tertiary children's hospitals.

CTK, CareTrack Kids; NSW, New South Wales; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia.

Medical record sampling per HCP

HCPs that agree to participate will be asked to provide de-identified lists of children who meet the criteria for inclusion that is, those aged <16 years who presented with 1 of the 16 conditions during 2012 and 2013. The records of each HCP will be stratified and a random selection of records will be selected from each strata using SAS randomisation script.

The number of records collected per HCP will be:

Twenty-five records per GP (five records each from five conditions);

Five records per specialist/clinical psychologist practice (five records from one condition);

A maximum of 100 records from each hospital (all conditions).

Component 4: resolve data management requirements and structure

A web-based tool developed for the CTA study14 to enter data during MRR and subsequent data analysis, will be modified to include the CTK paediatric conditions and indicators. The tool will support secure data access, data encryption, off-line data collection and subsequent database synchronisation (in order to mitigate against the problems of fire-walls and poor internet connectivity in various healthcare settings).

Given the complexity of the indicator set, the tool will generate a set of indicators relevant to a particular condition, based on participant demographic information, such as age. For example, the database will automatically filter out children without asthma aged <5 and >12 years if the indicator is “Children aged 5–12 years with mild frequent intermittent asthma are prescribed inhaled short acting beta2 agonists.” Algorithms will also filter indicators by the type of healthcare facility or practice. For example, the indicator for children diagnosed with mild or moderate croup presenting to an ED will not appear in the list of indicators to be reviewed in the GP setting. This will significantly reduce the workload on surveyors as only relevant indicators need to be reviewed.

Component 5: undertake pilot study

Given the scale and complexity of the full study, a pilot study involving a review of 200 medical records across all HCP types will be undertaken. This will help determine the types of problems that may be encountered and will inform the final selection (as described in component 1) of conditions, their indicators, and the logistical and practical aspects of recruiting participants and HCPs, of accessing records, and of extracting, recording, storing, and analysing the data. It will also inform the adjustments required to the sample size calculations in relation to non-response and design effects. The data obtained from the pilot will not be included in the main results.

Component 6: recruit HCPs

Recruitment of HCPs will follow the sampling procedures described in component 3. Invitations will be sent to chief executives (geographical areas and/or hospitals), general managers, specialists and practice managers requesting participation in the study. Owing to the large number of GPs within each geographical area a random sample (as described in component 3) of practices will be generated, creating a list of practices to invite initially. GPs that decline participation will be replaced by the next GP on the list until the required number of practices is reached.

Component 7: recruit surveyors

Registered nurses with a broad range of clinical knowledge, computer literacy and previous experience in MRR and clinical audit will be employed to act as surveyors to collect the data. Eight full-time equivalent staff will be required. During the employment process, prospective surveyors will participate in a test which involves the review of a mock medical record by coding indicators for each condition under time constraints (inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided for each indicator). Those applicants who score 90% or greater against one of the CTK researchers (a clinician who is involved in the condition clinical practice guideline searches, recommendation extraction, rewording of proposed indicators and will supervise the writing of the indicator inclusion/exclusion criteria) will be considered for appointment.

Component 8: train and quality check surveyors, measure inter-rater reliability

Training

Surveyors will participate in a training week which will include further mock MRRs; education on condition level information such as the evidence in the literature and CPGs; indicator inclusion and exclusion criteria; assessment and management procedures; inter-rater reliability (IRR) testing database orientation and training.

Inter-rater reliability

κ Scores will be calculated to test the level of agreement between each surveyor and one of the CTK researchers. Each surveyor must achieve a κ score of 0.8 before collecting data. After the first 2 weeks of data collection another IRR test will be undertaken to assess progress. IRR results of 0.8 are acceptable for the surveyor to continue. Surveyors scoring less than 0.8 will be provided with training and re-evaluated. Surveyors unable to achieve this target will be redeployed within the project.

Other quality assurance activities

A comprehensive instruction manual will be developed prospectively which provides condition level information, indicator inclusion and exclusion criteria, and directions for use of the database, as used in the CTA study. Weekly teleconferences will be conducted to share expertise and address problems. Questions and scenarios provided in this forum will be collated and the responses forwarded to each surveyor.

Component 9: undertake medical record reviews

Surveyors will undertake criterion-based26 MRR using the data tool (see component 4). MRRs will be conducted for each participant–HCP encounter (therefore more than one MRR may be undertaken for a participant). Surveyors will assess the record for evidence that the participant presented for treatment for the condition. The surveyor will respond to each indicator as ‘Yes’ (care provided during the encounter was consistent with the indicator), ‘No’, or ‘Not Applicable’ (NA; the indicator was not relevant to the encounter). For example, NA will be assigned to those indicators that relate to a new diagnosis if the participant was already documented to have that condition. For all indicators, a text field is available for surveyors to explain the reason for their answer.

Component 10: analyse data

The final sample will be weighted to the general population using prespecified survey weights for state, geographical location, geographical area and HCP type (as per table 2). The primary outcome is to report the percentage of eligible healthcare encounters at which appropriate care was received, analysed by aggregating percentage compliance for all conditions. Secondary outcomes are the percentage of appropriate care stratified by state, geographical location (metropolitan vs regional), and stages of care (screening, diagnosis, treatment, ongoing management). These will be analysed and reported by aggregating all conditions. The corresponding 95% exact binomial CI will be calculated.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

Relevant Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) approvals have been secured and Site-Specific Approvals will be sought and received prior to participant and healthcare practice recruitment and MRRs in all jurisdictions, authorities and health services. Single ethical review approval has been provided from a lead HREC in each state in order to provide ethical approval for the hospitals within that state. The lead HRECs include: Sydney Children's Hospitals Network (15 New South Wales hospitals), Queensland Royal Children's Hospital (12 Queensland hospitals) and Women's and Children's Health Network (8 South Australian hospitals). The Royal College of General Practitioners National Research and Ethics Evaluation Committee application is under review. Site-specific approvals will be sought from each hospital.

In all Human Research Ethics Committee applications (as named above) we proposed that patient and individual HCP consent be waived as the project complies with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) “Guidelines approved under Section 95A of the Privacy Act 1988”27 and the NHMRC Chapter 2.3.10 “Qualifying or waiving conditions for consent.”28 In summary the study involves: minimal risk (to HCPs and participants) and cannot be achieved without access to records; with dispersed geographic areas across three states, the large number of HCPs and records (6000–8000) it is logistically difficult to obtain consent; information is retrospective and there is no likely reason patients would not consent; data are entered directly onto a database which does not contain personal information; and only aggregated data are disseminated.

Statutory immunity

Statutory immunity protects participants from disclosure of any identifying information obtained through an approved quality assurance activity.29 CTK has applied to the Federal (Commonwealth) Minister for Health for statutory immunity under Section VC of the Commonwealth Health Insurance Act 1973.

Dissemination

The results of the study will be submitted to relevant national and international journals with the intention of publishing the results widely. The authors will offer oral presentations to stakeholder groups including those involving patients, researchers, clinicians, managers and policymakers at national and international conferences.

Discussion

We recognise several potential limitations to our study. HCPs will be invited to participate. Practices which agree may introduce a selection bias as they may have a higher rate of participation in research, proactive audit and existing feedback processes and hence a higher level of compliance. We consider this bias to be low as recognised in our CTA results where compliance ranged from 32% to 86%.14 Retrospective MRRs done retrospectively does not capture the exact compliance of care which is received but not documented, thought to be generally about 5%.15 30

In summary, CTK will, for the first time in Australia, provide information at a population-level regarding the appropriateness of healthcare delivered for children for a range of conditions. Furthermore, baseline appropriateness data will be available which could provide the basis for ongoing monitoring processes in Australia overall, state and regional areas which may be of value to national and international researchers, policymakers, patient groups and practitioners.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB and PDH initiated the project and led the NHMRC grant proposal. JB, AJ, LW, CTC and MFH led the design of the grant and shared in the development of the protocol and the initial drafting of the grant application and protocol. TDH, PDH, NM and LKW did the first drafting of the protocol manuscript. WBR, SG, ARH, JGW, EM, AL, GW, HMW and CFH helped write the grant proposal, protocol and manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Grant APP1065898. It is led by the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University. The partners in the research are BUPA Health Foundation Australia (senior partner), Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, NSW Kids and Families, Children's Health Queensland, the South Australian Department of Health, the University of South Australia (UniSA) and the NSW Clinical Excellence Commission.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee approvals have been received from the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service and Women's and Children's Health Network (SA).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Geographic Variations in Health Care. OECD Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwolsman S, Te Pas E, Hooft L et al. Barriers to GPs’ use of evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e511–21. 10.3399/bjgp12X652382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runciman WB, Coiera EW, Day RO et al. Towards the delivery of appropriate health care in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:78–81. 10.5694/mja12.10799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Clinical Practice Guidelines portal 2011. http://www.clinicalguidelines.gov.au/

- 5.National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for acute stroke management. National Health and Medical Research Council, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma Management Handbook 2006. National Asthma Council, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000326 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cretikos MA, Valenti L, Britt HC et al. General practice management of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Australia. Med Care 2008;46:1163–9. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318179259a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare. National strategy to address healthcare associated infections. Fourth Report to the Australian Health Ministers Conference. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring. Asthma in Australia 2011. Canberra, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuang A, Jaffe A. Cost considerations of therapeutic options for children with asthma. Pediatr Drugs 2012;14:1–10. 10.2165/11597360-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Ormiston TM et al. Meta-analysis: effect of long-acting beta-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:904–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt TD, Ramanathan SA, Hannaford NA et al. CareTrack Australia: assessing the appropriateness of adult healthcare: protocol for a retrospective medical record review. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000665 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. 10.5694/mja12.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2635–45. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1515–23. 10.1056/NEJMsa064637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiles LK, Hooper TD, Hibbert PD et al. CareTrack Kids—part 1 assessing the appropriateness of healthcare delivered to Australian children: a study protocol for clinical indicator development. BMJ Open 2015. In press. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibbert PD, Hallahan AR, Muething SE et al. CareTrack Kids—part 3 adverse events in children's healthcare in Australia: study protocol for a retrospective medical record review. BMJ Open 2015. In press. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiscock H, Roberts G, Efron D et al. Children Attending Paediatricians Study: a national prospective audit of outpatient practice from the Australian Paediatric Research Network. Med J Aust 2011;194:392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg S, Vos T, Barker B et al. The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Canberra: AIHW, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Health Priority Areas. Canberra: AIHW, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olds TS, Tomkinson GR, Ferrar KE et al. Trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in Australia between 1985 and 2008. Int J Obes 2010;34:57–66. 10.1038/ijo.2009.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzgerald A, Mori R, Lakhanpaul M et al. Antibiotics for treating lower urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD006857 10.1002/14651858.CD006857.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheaffer R, Mendenhall W, Ott R, et al. Elementary survey sampling. 7th edn. Cengage Learning, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census 2011. Quickstats 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/quickstats?opendocument&navpos=220 (accessed 1 Dec 2012).

- 26.Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A et al. An epistemology of patient safety research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 3. End points and measurement. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17: 170–7. 10.1136/qshc.2007.023655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Guidelines approved under Section 95A of the Privacy Act 1988 Canberra, 2014. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/pr2_guidelines_under_s95a_of_the_privacy_act_140311.pdf

- 28.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (revised march 2014) Canberra, 2014. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/e72_national_statement_march_2014_140331.pdf

- 29.Commonwealth Government, ed. Health Insurance Act Part VC—(Quality Assurance Confidentiality). Canberra, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Runciman W, Hunt T, Hannaford N et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:549–50. 10.5694/mja12.11210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]